Abstract

Cells lacking telomerase undergo senescence, a progressive reduction in cell division that involves a cell cycle delay and culminates in “crisis,” a period when most cells become inviable. In telomerase-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells lacking components of the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) pathway (Upf1,Upf2, or Upf3 proteins), senescence is delayed, with crisis occurring ∼10 to 25 population doublings later than in Upf+ cells. Delayed senescence is seen in upfΔ cells lacking the telomerase holoenzyme components Est2p and TLC1 RNA, as well as in cells lacking the telomerase regulators Est1p and Est3p. The delay of senescence in upfΔ cells is not due to an increased rate of survivor formation. Rather, it is caused by alterations in the telomere cap, composed of Cdc13p, Stn1p, and Ten1p. In upfΔ mutants, STN1 and TEN1 levels are increased. Increasing the levels of Stn1p and Ten1p in Upf+ cells is sufficient to delay senescence. In addition, cdc13-2 mutants exhibit delayed senescence rates similar to those of upfΔ cells. Thus, changes in the telomere cap structure are sufficient to affect the rate of senescence in the absence of telomerase. Furthermore, the NMD pathway affects the rate of senescence in telomerase-deficient cells by altering the stoichiometry of telomere cap components.

Telomeres, the chromosome ends, are composed of highly repetitive DNA that is synthesized by telomerase, a specialized reverse transcriptase with an integral RNA template sequence. Both telomeres and telomerase are important determinants of a mitotic clock that regulates the proliferative potential of cells (1). In the absence of telomerase or when telomeres become critically short, cells senesce, exhibiting a progressively slower rate of cell division that involves a cell cycle delay (11, 24). Germ line cells and most somatic stem cells have high levels of telomerase and long telomeres. In most somatic cells, telomerase is inactive and telomere sequences erode at variable rates, depending upon the organism and cell type (18). For example, when primary fibroblasts are cultured, they typically undergo a limited number (50 to 100) of divisions prior to senescence and eventual death of almost all cells in the culture. This point of maximal cell death is termed “crisis.” Rare cells that survive crisis and become immortalized, including the majority of cancer cell types and the rare cultured cells that do not senesce, usually have high levels of telomerase activity (20). Furthermore, expression of the catalytic subunit of telomerase is sufficient to immortalize several different cell types in culture (2, 26, 51, 52), indicating that the lack of telomerase activity in somatic cells limits the proliferative potential of those cells.

In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, telomerase is composed of Est2p (32) and TLC1, the telomerase template RNA (44). Deletion of either EST2 or TLC1 causes a progressive shortening of telomeres and eventual loss of culture viability (35) that is analogous to the replicative senescence of cultured human fibroblasts. The increasing cell cycle delay that characterizes senescence prior to crisis involves a distinct set of checkpoint genes, including MEC1 and MEC3 (11). As with fibroblast cultures, continued subculturing of telomerase-deficient yeast gives rise to rare survivor cells that ultimately overtake cultures of primarily senescing and dying cells (29, 35, 44, 49, 50). In S. cerevisiae, telomerase-deficient survivor cells have two types of altered telomeric DNA structure. In type I survivors, the subtelomeric repeat sequences (STRs) have been rearranged and amplified (35), while in type II survivors, very long terminal repeat sequences (C1-3A) are generated (50). The formation of both types of survivors depends upon the product of the RAD52 gene (35, 50).

EST1, EST3, and CDC13/EST4 also contribute to telomerase function. While the products of these genes are not required for telomerase activity in vitro (32), mutations in these genes cause telomere erosion and eventual senescence phenotypes like those seen in est2Δ or tlc1Δ strains. Furthermore, genetic analysis places all four EST genes and TLC1 in the same pathway (29). Est1p and Est3p are tightly associated with telomerase RNA and telomerase activity (12, 22, 31, 47, 55) and are likely components of the telomerase complex in vivo (29). CDC13 encodes a protein that binds to the telomeric single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and is crucial in protecting telomere integrity and regulating telomere replication, including telomerase access (4). Cdc13p, along with Stn1p and Ten1p, is proposed to form a “telomere cap” that serves to protect the chromosome end and to regulate access of the telomere to the telomerase enzyme (36). STN1 encodes an essential protein that limits the recruitment of telomerase to the telomere and protects chromosome ends from homologous recombination (10, 14). TEN1 encodes an essential gene of unknown function that is required for telomere length regulation (16).

In previous work, we identified mutations in the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) pathway that affected several telomere functions (30). The NMD pathway targets mRNAs for nuclease destruction (8). Three genes, UPF1, UPF2, and UPF3, contribute to the NMD pathway (8) and affect telomere length regulation, telomeric silencing, and the localization of Rap1p, a telomere binding protein, within yeast nuclei (30). Telomerase-proficient upf mutants have telomeres that are ∼100 bp shorter than wild-type telomeres, exhibit a loss of telomeric silencing, as well as a loss of TEL+CEN antagonism (30). The NMD pathway affects the steady-state levels of several hundred native yeast transcripts, as determined by analysis of high-density oligonucleotide arrays (HDOAs) (28). Several genes that control telomerase activity, including EST1, EST2, EST3, and STN1, are regulated by NMD (9). A human gene encoding a protein with similarity to Est1p (40, 46) recently was identified as a component of the NMD pathway as well (7).

In this paper, we demonstrate that the NMD pathway accelerates the rate of senescence in telomerase-deficient yeast cells. Deletion of either UPF1, -2, or -3 causes delayed senescence in cells lacking either EST1, EST2, EST3, or TLC1. This delay in senescence does not require RAD52 and is not due to the increased formation of survivors. Loss of the NMD pathway causes increased expression of STN1, a binding partner of Cdc13p. Moreover, when STN1 expression is uncoupled from NMD regulation, the delay in senescence in upf mutants is lost. Thus, upf mutants delay senescence by altering levels of the cap component Stn1p. Furthermore, an altered cap structure in cdc13-2 cells results in delayed senescence that is not dependent upon the NMD pathway. This is consistent with the fact that the cdc13-2 mutation affects interactions with Stn1p (4), and levels of CDC13 mRNA are not affected in upf mutants. Thus, altering the telomere end protection protein Stn1p or its interaction with Cdc13p affects the rate of senescence. We propose that senescence, triggered by a cellular response to the loss of telomerase or the erosion of telomeres, is an active process that is accelerated by the wild-type NMD pathway through a mechanism that involves the chromosome end protection components STN1 and CDC13.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, plasmids, and Southern analysis.

All strains used in this study were isogenic with W303 and are listed in Table 1. The TLC1 disruption was made by one-step gene replacement with plasmid pBlue61::LEU2 (44) in strain YJB334. The est1::URA3 allele was obtained from B. Futcher in strain KH000 (47). EST2 and EST3 disruptions were made by one-step gene replacement with plasmids pVL523 and pVL418, respectively (37), in strain YJB334. The cdc13-1 allele was introduced into YJB195 by using pVL451 (37), and the cdc13-2 allele was introduced into YJB2677 by using pVL437 (37). Telomerase-deficient isolates from early passages were used in standard crosses. The upf1::HIS3, upf2::HIS3, and upf3::HIS3 alleles were obtained from A. Jacobson in strains HFY871, HFY116, and HFY861, respectively (21). The rad52::TRP1 allele was obtained from P. Kaufman in strain PKY065 (13). All of these alleles were introduced into the W303 strain background by standard crosses and multiple backcrosses. Sporulation and tetrad dissection were performed according to standard methods (43). Strains were maintained in standard yeast media (42).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| YJB195 | MATaura3-1 ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 can1-100 trp1-1 |

| YJB334 | MATa/α ura3-1 ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 can1-100 trp1-1 |

| YJB2213 | MATa/α est1Δ::URA3/EST1 ufp2Δ::HIS3/UPF2 |

| YJB2659 | MATa/α est2Δ::URA3/EST2 ufp2Δ::HIS3/UPF2 VR-ADE2-TEL/VR-TEL |

| YJB2677 | MATaura3-1 ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 can1-100 trp1-1 cdc13-1(ts−) |

| YJB2689 | MATa/α est3Δ::URA3/EST3 ufp2Δ::HIS3/UPF2 VR-ADE2-TEL/VR-TEL |

| YJB2751 | MATanmd2::his3::LEU2 VR-ADE2-TEL/VR-TEL |

| YJB2857 | MATa/α cdc13-2 (est4)/CDC13::URA3::cdc13-1 ufp2Δ::HIS3/UPF2 |

| YJB2937 | MATa/α cdc13-2 (est4)/CDC13::URA3::cdc13-1 ufp2Δ::HIS3/UPF2 tlc1Δ::LEU2/TLC1 VR-ADE2-TEL/VR-TEL |

| YJB3194 | MATa/α CDC13::URA3::cdc13-1/cdc13-1Ts−ufp2Δ::HIS3/UPF2 |

| YJB3645 | MATa/α est1Δ::URA3/EST1 ufp2Δ::HIS3/UPF2 hmrΔA::TRP1/HMR::TRP1 |

| YJB3685 | MATa/α tlc1Δ::LEU2/TLC1 ufp1Δ::HIS3/UPF1 VR-ADE2-TEL/VR-TEL |

| YJB3686 | MATa/α tlc1Δ::LEU2/TLC1 ufp2Δ::HIS3/UPF2 VR-ADE2-TEL/VR-TEL |

| YJB3993 | MATa/α tlc1Δ::LEU2/TLC1 ufp3Δ::HIS3/UPF3 VR-ADE2-TEL/VR-TEL |

| YJB3994 | MATa/α est2Δ::URA3/EST2 ufp3Δ::HIS3/UPF3 VR-ADE2-TEL/VR-TEL |

| YJB3996 | MATa/α est1Δ::URA3/EST1 ufp3Δ::HIS3/UPF3 HMLa/HMLα VR-ADE2-TEL/VR-TEL |

| YJB5129 | MATa/α est1Δ::URA3/EST1 ufp2Δ::HIS3/UPF2 rad52Δ::RAD52 |

| YJB5756 | MATa/α CDC13::URA3::cdc13-1/cdc13-2 (est4) ufp1Δ::HIS3/UPF1 |

| YJB5775 | MATa/α est2Δ::URA3/EST2 ufp1Δ::HIS3/UPF1 ufp2Δ::HIS3/UPF2 |

| YJB5776 | MATa/α est2Δ::URA3/EST2 ufp1Δ::HIS3/UPF1 ufp3Δ::HIS3/UPF3 |

| YJB5935 | MATa/α tlc1Δ::LEU2/TLC1 ufp2Δ::HIS3/ufp2Δ::HIS3 VIIL::URA3/VIIL VR-ADE2-TEL/VR-TEL |

| YJB5936 | MATa/α tlc1Δ::LEU2/TLC1 ufp1Δ::HIS3/UPF1 ufp2Δ::HIS3/UPF2 VIIL::URA3/VIIL VR-ADE2-TEL/VR-TEL |

| YJB6411 | MATa/α mec3Δ::TRP1/MEC3 tlc1Δ::LEU2/TLC1 ufp2Δ::HIS3/UPF2 |

| YJB7492 | MATa/α est2Δ::URA3/EST2 ufp2Δ::HIS3/UPF2 VR-ADE2-TEL/VR-TEL TRP1::PGAL1-STN1/STN1 (YEPlac181) |

| YJB7590 | MATa/α est2Δ::URA3/EST2 ufp2Δ::HIS3/UPF2 VR-ADE2-TEL/VR-TEL TRP1::PGAL1-STN1/STN1 (YEPlac181) p1916 (YEP TEN1 LEU2) |

| YJB7722 | MATa/α tlc1Δ::URA3/TLC1 ufp2Δ::HIS3/UPF2 VR-ADE2-TEL/VR-TEL p2022 (2μm PGAL1-TEN1 LEU2) |

PGAL1-STN1 was constructed in YJB2751 by introducing the GAL1 promoter immediately 5′ of the initiation codon of STN1. The GAL1 promoter was amplified by PCR from pFA6a-TRP1MX6-pGAL1 (33) with oligonucleotides 1021 (5′ATAACAAACARCGCCTTCTTGATGACCTATATGTCCGTACTTHTCCATTTTGAGATCCGGGTTTT3′) and 1022 (5′AAAGAAGTAAGCATTGGAATATATGAAATCCTGCTTGTTGATATTGAATTCGAGCTGTTTAAAC). Yep-GAL-TEN1 was obtained from M. Charbonneau (15).

Southern blots of the telomere terminal repeat were performed essentially as described previously (9, 30).

Serial passages of senescing cultures.

Telomerase-deficient cells were obtained by sporulation and dissection of the appropriate heterozygous diploids (YJB3685, YJB2213, YJB2659, YJB2689, YJB2857, and YJB7492). After tetrad dissection, spore colonies grew for 2 days on solid medium at 30°C and were suspended in 15% glycerol, and then ∼105 cells were inoculated into 1 ml of YPAD medium (42). Liquid cultures were grown for 24 h at 30°C, at which point they had typically completed 10 population doublings (PDs) and had reached stationary phase. The 24-h liquid cultures (passage 1) were diluted 1:1,000 into fresh YPAD medium and grown for 24 h at 30°C (passage 2). Six serial cultures were generated by successive dilutions (1:1,000) of the previous 24-h culture. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured for each isolate at each passage. The number of population doublings a culture underwent during the 24-h period was calculated by the following formula: log2 [(ending OD600 × 1,000)/starting OD600].

To quantitate the colony size of the senescing colonies, spore colonies isolated immediately after sporulation of tlc1Δ/TLC1 upf2Δ/UPF2 parents were serially advanced in liquid medium for 10 PDs as described above. Cells from 45, 55, 65, and 75 PDs were then plated on solid medium and allowed to form colonies for 24 h at 30°C, and the colony area of 100 colonies of each genotype was measured. Images of colonies from each passage were captured with a Nikon Cool Pix 900 digital camera mounted on a Zeiss stereoscope Stemi DRC (Sterling Heights, Mich.).

Crisis was defined as the point of minimum PDs per 24-h period. Statistical analysis was performed for comparison of the number of PDs the UPF and upfΔ telomerase-deficient strains underwent before crisis. The rank sum test was used to compare the medians (45). Median differences with confidence limits were obtained by the method of Hodges-Lehmann (45).

Western analysis.

Liquid cultures of exponentially growing wild-type and upf2Δ strains containing Stn1-cMyc at its native locus were harvested, washed twice with 1× phosphate-buffered saline, and resuspended in 50 μl of lysis buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 8 M urea, 0.1 M EDTA). The tubes were immediately vortexed with 250 μl of glass beads for 90s and heated to 70°C for 3 min, and 250 μl of protein loading buffer was added for 5 min at 70°C. The resulting lysates were centrifuged for 10 min. The protein concentration in the supernatant was determined by A280 units, and 50 U was run on an 8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gel. Western analysis was performed with anti-cMyc antibody (1:10,000) followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antimouse secondary antibody (1:45,000). Anti-PGK antibody was used to detect Pgk1p as a control for gel loading. All antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, Calif.).

RESULTS

Loss of nonsense-mediated decay delays senescence in telomerase-deficient cells.

In S. cerevisiae, deletion of the catalytic subunit of telomerase (EST2), the template RNA (TLC1), or the accessory factors (EST1 and EST3) causes progressive telomere shortening and eventual senescence of the population (29). Senescence can be observed as a decrease in culture growth upon serial passaging in liquid medium (liquid passages, Table 2). When we isolate telomerase-deficient cells as fresh spore progeny from heterozygous parents (see Materials and Methods for details), they can be passaged for approximately six serial cultures (24 h at 30°C in YPAD medium) before crisis (the state in which very few viable cells are present) occurs. To quantitate senescence in upfΔ telomerase-deficient mutants, we used liquid passages to estimate the total number of PDs between sporulation and crisis, defined as the passage of minimum growth. We isolated spore colonies immediately postmeiosis and sporulation and serially passaged the cells in liquid medium for 8 consecutive days (1:1,000 dilutions followed by growth for 24 h at 30°C). During early passages, population growth was limited to approximately 10 PDs per day by crowding of the culture. In the middle passages, cultures did not reach saturation (∼4 to 9 PDs per day) due to slower growth caused by activation of the telomere checkpoint (11). During the late passages, following the crisis period, viability increased again due to the formation of telomerase-independent survivors (27, 35, 50), and population growth was again limited by saturation of the culture at 10 PDs per day.

TABLE 2.

upf2Δ delays senescence in telomerase mutants

| Genotype | Median PD | n | Median differencea | Lower limit | Upper limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| est1Δ | 60 | 6 | |||

| est1Δ upf2Δ | 82 | 6 | 25* | 18 | 36 |

| est2Δ | 61 | 6 | |||

| est2Δ upf2Δ | 76 | 6 | 23* | 11 | 34 |

| est3Δ | 62 | 6 | |||

| est3Δ upf2Δ | 91 | 6 | 28* | 21 | 29 |

| tlc1Δ | 55 | 6 | |||

| tlc1Δ upf2Δ | 83 | 6 | 26* | 19 | 33 |

| cdc13-2 | 79 | 6 | |||

| cdc13-2 upf2Δ | 81 | 6 | 3 | −16 | 11 |

*, significant (P < 0.05) median difference (Hodges-Lehmann estimator) (45). n = number of independent isolates.

The NMD pathway, which consists of a recognition module encoded by UPF1, UPF2, and UPF3 (8), affects the steady-state levels of mRNAs that encode telomerase and telomerase regulators, including EST1, EST2, and EST3 (9, 28). To gain further insight into interactions between the NMD pathway and telomere metabolism, we analyzed double mutants defective in both NMD and telomerase function. To generate telomerase-deficient NMD-deficient clones, diploid strains heterozygous for telomerase components or regulators and heterozygous for UPF mutations were sporulated, and the growth of cultures that arose from individual spores was monitored through serial passages in liquid medium. We initiated these studies by using a deletion allele of EST1 (est1Δ). When EST1/est1Δ UPF2/upf2Δ heterozygous diploids were sporulated, the est1Δ UPF spore progeny reached crisis at ∼60 PDs after meiosis and sporulation (Table 2). Interestingly, est1Δ upf2Δ sibling cultures grew and divided significantly longer (82 PDs with a median difference of 25 PDs) than the est1Δ UPF2+ cultures (Table 2). In both cultures, survivors arose in later passages.

To determine if the delay in senescence observed in est1Δ upf2Δ strains was specific for EST1 or due to loss of telomerase activity in vivo, we constructed the appropriate double mutant strains lacking upf2 and either EST2, EST3, or TLC1 RNA and monitored the growth of these strains in serial liquid passages. As with the est1Δ upf2Δ cultures, est2Δ upf2Δ, est3Δ upf2Δ, and tlc1Δ upf2Δ strains senesced 23 to 28 PDs later than the corresponding UPF+ strains (Table 2), indicating that the delay in senescence due to upf mutations is not specific for est1Δ strains. EST1, EST2, and EST3 mRNA levels are regulated by the NMD pathway (9, 28), while levels of TLC1 RNA are not (9). Yet the upf2Δ mutant had a similar rate of senescence when present with est1Δ, est2Δ, est3Δ, or tlc1Δ mutations. Thus, the mechanism by which the upf2Δ mutation delays senescence remains intact in all of these telomerase-deficient strains and cannot occur through regulation of the stability of EST1, EST2, or EST3 mRNAs.

Upf1p, Upf2p, and Upf3 are all required to target mRNAs for NMD-mediated decay (28). To determine if the delay in senescence in upf2Δ telomerase-deficient strains was due to a specific function of Upf2p or was the result of loss of the NMD pathway, we analyzed the senescence of telomerase-deficient strains lacking Upf1p or Upf3p. As with tlc1Δ upf2Δ strains, tlc1Δ upf1Δ and tlc1Δ upf3Δ strains exhibited a significant delay in senescence relative to the corresponding UPF+ telomerase-deficient strains (Table 3). Furthermore, a tlc1Δ upf1Δ upf2Δ triple mutant senesced at the same rate as the tlc1Δ upf1Δ double mutant (Table 3). Thus, loss of the NMD pathway, rather than loss of UPF2 specifically, delays senescence in telomerase-deficient strains.

TABLE 3.

Loss of the NMD pathway delays sensescence in telomerase RNA mutants

| Genotype | Median PD | n | Median differencea | Lower limit | Upper limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tlc1Δ | 55 | 6 | |||

| tlc1Δ upf2Δ | 83 | 6 | 26* | 19 | 33 |

| tlc1Δ | 53 | 6 | |||

| tlc1Δ upf1Δ | 71 | 6 | 19* | 18 | 20 |

| tlc1Δ | 56 | 7 | |||

| tlc1Δ upf3Δ | 73 | 7 | 16* | 11 | 17 |

| tlc1Δ upf1Δ | 71 | 8 | |||

| tlc1Δ upf1Δ upf2Δ | 73 | 8 | .4 | −0.05 | 1.3 |

*, significant (P < 0.05) median difference (Hodges-Lehmann estimator) (45). n = number of independent isolates.

Senescence progresses more slowly in upf telomerase-deficient strains.

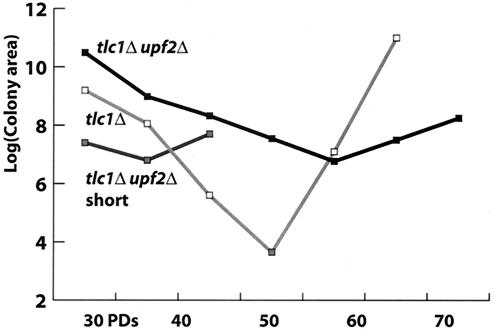

The senescence delay observed in upfΔ mutants could be caused by later onset of the senescence program or by slower progression of the senescence process. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we monitored the culture growth rate soon after the loss of telomerase. Quantitation of the number of PDs that a culture underwent allowed us to determine the timing of senescence. Following the loss of telomerase, the cell division rate decreased progressively as telomerase-deficient cells were cultured. This resulted in the formation of progressively smaller colonies, progressively larger individual cells, and an increasing delay in the G2/M stage of the cell cycle (11). The decrease in colony size can be observed as early as the first passage after sporulation. Measurement of colony area after 24 h of plating on solid medium provides a reproducible measure of the growth rate of the culture (11) and should indicate whether upfΔ telomerase-deficient cells senesce more slowly (slope of the curve is more shallow) or initiate senescence later (decrease in colony area begins later) than corresponding UPF telomerase-deficient cells.

During the serial passages, both the tlc1Δ and tlc1Δ upf2Δ colonies formed increasingly smaller colonies. However, the size of the tlc1Δ colonies decreased more rapidly (slope = −1.9) than the decrease in the sizes of the tlc1Δ upf2Δ colonies (slope = −0.77) (Fig. 1). This indicates that the tlc1Δ cells senesce about twice as fast as the tlc1Δ upf2Δ cells and implies that the senescence delay in upf2Δ cells is due to a slower progression of the senescence program rather than to a delay in the onset of senescence.

FIG. 1.

Kinetics of senescence is altered in upf mutants. The log colony area of senescing colonies was measured and plotted against the number of PDs the culture had undergone. tlc1Δ UPF2 isolates from diploid strain YJB3686 are shown by the light gray boxes and line, tlc1Δ upf2Δ isolates from diploid strain YJB3686 are shown by the black boxes and line, and tlc1Δ upf2Δ isolates from diploid YJB5935 with short starting telomeres are shown by the medium gray boxes and line. Note that the tlc1Δ upf2Δ strain YJB5935 with short starting telomeres formed survivors within one to two passages after meiosis.

Telomere length erosion rates are similar in wild-type and upfΔ strains.

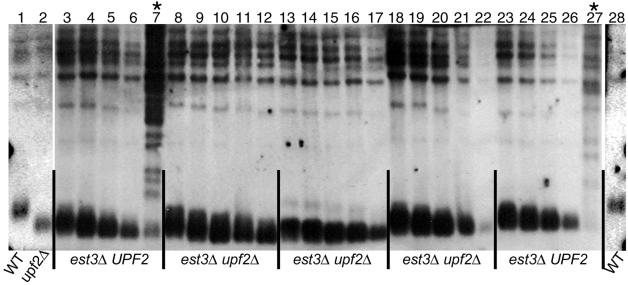

One possible mechanism for the delay of senescence in upfΔ telomerase-deficient strains may be a slower rate of telomere DNA length erosion. We compared the terminal restriction fragment lengths of est3Δ and est3Δ upf2Δ spore progeny by Southern analysis of serial passages in liquid media. Genomic DNA was prepared from serial passages of est3Δ and est3Δ upf2Δ spores and digested with PstI, which releases an ∼0.8-kb heterodisperse band from the terminus of all chromosomes that have Y′ telomere-associated sequences that can be detected with a telomeric (Y′+TG1-3) probe. In telomerase-deficient UPF strains (Fig. 2), the terminal PstI fragment became shorter, exhibiting a faster average electrophoretic mobility with increasing numbers of PDs after loss of Est3p. Additional Y′-hybridizing bands, characteristic of type II survivors, were evident in the est3Δ survivor culture by ∼80 generations (Fig. 2, lanes 7 and 27). In contrast, telomeres in the three est3Δ upf2Δ isolates at similar generation times did not undergo obvious rearrangements or amplification of Y′ sequences. This indicates that no obvious amplification or rearrangement of TASs or TG1-3 repeats occurred within the PDs analyzed. Like the telomerase-deficient UPF strains, the terminal PstI restriction fragment migrated with increasing mobility as cells underwent more PDs. Telomere length erosion in the est3Δ upf2Δ strains appeared to occur at rates similar to the rate of telomere erosion in the est3Δ UPF2 strain (Fig. 2) (data not shown). From our Southern analysis, we cannot rule out the possibility that the rate of telomere erosion in est upf strains was slightly slower than the rate in est strains. Similar telomere length erosion rates also were observed when estΔ mutant strains were compared to the appropriate estΔ upfΔ strains (data not shown). Thus, loss of the NMD pathway did not delay senescence by increasing the rate of terminal fragment rearrangements that are characteristic of survivor formation. Furthermore, the obvious shorter telomere length seen in upfΔ telomerase-proficient cells (28) is not evident in upfΔ telomerase-deficient cells. This suggests that the short-telomere phenotype of upfΔ mutants requires active telomerase.

FIG. 2.

Rate of telomere length change does not differ between telomerase-deficient and telomerase-deficient NMD-deficient strains. Total genomic DNA was digested with PstI and separated in 1% agarose. Lanes 1 and 28, wild type (WT; YJB209), lane 2, EST3 upf2Δ (isolate from diploid strain YJB1274) taken at ∼30, 40, 50, 60 and 70 PDs, lanes 3 to 7 and 23 to 27, serial passages of est3Δ UPF2 taken at ∼30, 40, 50, 60, and 70 PDs (isolate from diploid strain YJB2689), lanes 8 to 12, 13 to 17, and 18 to 22, serial passages of est3Δ upf2Δ taken at ∼30, 40, 50, 60, and 70 PDs (isolate from diploid strain YJB2689). Cultures in lanes 7 and 27 were overtaken by survivors (marked with asterisks).

Onset of senescence is influenced by telomere length.

The telomere length analysis described above demonstrated that est3Δ upf2Δ telomeres are similar in size to telomeres in est3Δ single mutants. This was surprising because upfΔ mutants have shorter telomeres than do wild-type cells (30). The est3Δ upf2Δ strains may have wild-type telomere length because the spore progeny are isolated from a heterozygous UPF2/upf2Δ parent. To ask if the upf status of the parent has an effect on the telomere length of the progeny, we sporulated heterozygous UPF/upfΔ TLC1/tlc1Δ and homozygous upfΔ/upfΔ TLC1/tlc1Δ parents and analyzed telomere length and senescence in the spore progeny. Telomere length was shorter in the upfΔ/upfΔ parents relative to the UPF/upfΔ parents (data not shown). This indicates that the initial length of the upfΔ tlc1Δ strains is due to the wild-type length of telomeres in the heterozygous parent from which they were derived. tlc1Δ derivatives from the upfΔ/upfΔ parent grew poorly and reached crisis, forming survivors within one to two passages after sporulation (25 to 35 PDs) (Fig. 1). Progeny derived from the UPF/upfΔ parent reached crisis at ∼60 PDs. Therefore, initial telomere length appears to be an important determinant of the duration of senescence.

The delayed senescence in upfΔ telomerase-deficient strains is independent of RAD52 and MEC3.

In yeast strains lacking telomerase, a small subpopulation of cells escape senescence and form “survivors” that are viable, divide with wild-type rates, and rapidly overtake the culture of senescing cells (29, 35). Once this occurs, the viability of the cultures improves dramatically. A possible mechanism for the delay of senescence in upfΔ telomerase-deficient strains is an elevated frequency in the generation of survivors relative to that seen in UPF telomerase-deficient strains (48). RAD52 is required for the formation of both type I and II survivors in telomerase-deficient strains (6, 27). To ask if RAD52 is required for the delay in senescence observed in upfΔ telomerase-deficient strains, we compared the senescence of est1Δ rad52Δ and est1Δ rad52Δ upf2Δ strains immediately following the sporulation of heterozygous diploids. All rad52Δ cultures senesced faster than RAD52 strains. However, the est1Δ rad52Δ upf2Δ strains retained viability for significantly more PDs than the est1Δ rad52Δ UPF2 strains (Table 4), indicating that the delay of senescence in upfΔ cells occurs by a mechanism that is independent of RAD52. This result is consistent with the idea that upfΔ strains do not delay senescence by increasing the rate of survivor formation or by inducing survivor formation at an early time after the loss of telomerase.

TABLE 4.

Delayed senescence is independent of Rad52p and Mec3p

| Genotype | Median PD | n | Median differencea | Lower limit | Upper limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rad52Δ tlc1Δ | 35 | 11 | |||

| rad52Δ tlc1Δ upf2Δ | 47 | 11 | 10* | 2 | 19 |

| mec3Δ tlc1Δ | 56 | 6 | |||

| mec3Δ tlc1Δ upf2Δ | 95 | 6 | 39* | 22 | 40 |

*, significant (p < 0.05) median difference (Hodges-Lehmann estimator) (45). n = number of independent isolates.

Survivor formation is increased in haploid cells expressing both MATa and MATα information (34). To ask if upf mutants were delaying senescence by derepressing a mating information in a MATα upf telomerase-deficient strain, we compared the rate of senescence in a MATα upf2Δ est1Δ strain and a MATα upf2Δ est1Δ hmr1Δ strain. The rates of senescence in these two strains were indistinguishable. Thus, loss of NMD does not delay senescence by altering the expression of silent mating information.

In previous work, we found that senescence in telomerase-deficient cells is characterized by a Mec3-dependent telomere integrity checkpoint (11). To explore whether the MEC3-dependent checkpoint was activated in upf telomerase-deficient cells, we compared the senescence of mec3Δ tlc1Δ cells with that of mec3Δ tlc1Δ upf2Δ cells. Both strains exhibited senescence typical of mec3 strains during the first 75 PDs. As seen previously (11), crisis occurred in the mec3Δ tlc1Δ isolates after 56 PDs. In contrast, crisis occurred in the mec3Δ tlc1Δ upf2Δ isolates after 95 PDs (Table 4). Thus, the delayed senescence seen in upf strains is not due to changes in the Mec3-dependent telomere integrity checkpoint.

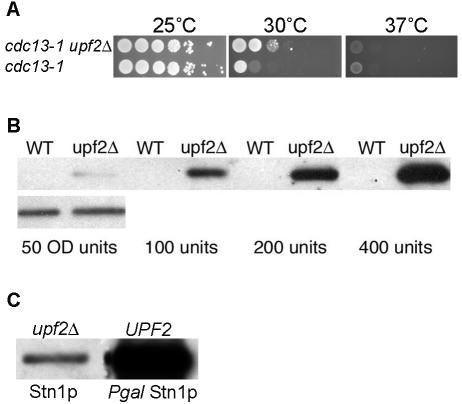

Senescence is delayed by constitutive expression of STN1.

STN1 is an essential gene that was identified as a dosage suppressor of a temperature-sensitive allele of CDC13 (cdc13-1) (17). Steady-state levels of STN1 mRNA are 2.55-fold higher in upfΔ strains than in isogenic wild-type strains (7). Stn1p and Cdc13p work cooperatively to regulate the access of telomerase to telomeric DNA (4, 14, 15, 53). cdc13-1 mutants are temperature sensitive: they grow well at 25°C, poorly at 30°C, and do not grow at all at 37°C (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, cdc13-1 upf2Δ strains grow better at 30°C, indicating that loss of NMD can partially suppress the temperature-sensitive phenotype of the cdc13-1 mutant (Fig. 3A). Since CDC13 mRNA levels are not altered in upfΔ mutants (9, 28), this result is consistent with the idea that Stn1p levels are increased in an upf2Δ mutant and that the extra Stn1p can suppress the cdc13-1 temperature sensitivity. To ask if Stn1p levels are elevated in upfΔ mutants, we also measured the levels of an epitope-tagged Stn1p expressed in wild-type and upfΔ strains. Stn1-cMyc is clearly detectable in upfΔ strains, while in W303 UPF+ strains, it is not detected (Fig. 3B). This may be due to differences between W303 and other strain backgrounds. In other work, Stn1p was detectable only when overexpressed (16). Thus, like STN1 mRNA levels, the steady-state levels of Stn1 protein are increased in upfΔ mutants.

FIG. 3.

Higher levels of Stn1p in upfΔ mutants. (A) Liquid cultures were serially diluted, applied as spots to solid medium, and grown at the indicated temperatures for 2 days. cdc13-1 mutants isolated from diploid strain YJB3194 grow poorly at 30°C and did not form colonies at 37°C. In contrast, upf2Δ cdc13-1 isolates from YJB3194 formed colonies at 30°C. (B) Western analysis of Stn1p-cMyc in wild-type (WT) and upf2Δ strains. (C) Western analysis of Stn1p-cMyc in an upf2Δ strain and GAL1-Stn1p-cMyc grown in galactose.

To determine whether high levels of Stn1p alone could confer a delay in senescence, we first analyzed the senescence of est1Δ progeny from a heterozygous EST1/est1Δ parent carrying YEP-STN1. Surprisingly, these progeny senesced more rapidly than est1Δ strains carrying the YEP vector alone (data not shown). However, high levels of Stn1p lead to telomere shortening (9). These parents and their progeny had shorter telomeres than the est1Δ strain carrying the vector alone. The est1Δ upf2Δ strains carrying YEP-STN1 exhibited delayed senescence relative to the est1Δ UPF2 strain carrying YEP-STN1. This supports the idea that the STN1 mRNA expressed from this plasmid remains under the control of the NMD pathway (9).

To ask if NMD regulation of STN1 is necessary for the senescence delay in telomerase-deficient cells, we constructed a strain expressing STN1 in a UPF-independent manner. The 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) of STN1 is sufficient to confer NMD regulation upon STN1 mRNA (9). To eliminate NMD regulation of STN1, we constructed PGAL1-STN1 by placing the GAL1 promoter sequences 5′ to the STN1 genomic open reading frame. If NMD regulation of STN1 is required for the NMD-dependent acceleration of senescence, we expect that a strain expressing PGAL1-STN1 strain would exhibit a similar senescence rate in UPF and upfΔ strains. All diploid parents carrying PGAL1-STN1 were maintained on glucose medium to ensure there was no effect on telomere length until after sporulation of the progeny. When PGAL1-STN1-cMyc strains were grown in galactose, we detected greater than 10-fold more Stn1p than in upf2Δ cells (Fig. 3C). In est2Δ cells expressing PGAL1-STN1, the deletion of upf2 had little effect on the rate of senescence (Table 5), indicating that upf regulation of STN1 contributes to the delayed senescence of upfΔ telomerase-deficient strains.

TABLE 5.

Overexpression of STN1 but not TEN1 phenocopies loss of the NMD pathway

| Genotype | Median PD | n | Median differencea | Lower limit | Upper limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| est2Δ PGAL1-STN1 | 53 | 6 | |||

| est2Δ PGAL1-STN1 upf2Δ | 65 | 6 | 10 | −0.6 | 13.9 |

| tlc1Δ YEP PGAL1-TEN1 | 62 | 11 | |||

| tlc1Δ YEP PGAL1-TEN1 upf2Δ | 80 | 11 | 17* | 10 | 19 |

| est2Δ PGAL1-STN1 + YEP-TEN1 | 64 | 10 | |||

| est2Δ PGAL1-STN1 + YEP-TEN1 upf2Δ | 64 | 8 | −0.3 | −0.8 | 0.04 |

*, significant (P < 0.05) median difference (Hodges-Lehmann estimator) (45). n = number of independent isolates.

TEN1 encodes an essential gene of unknown function that is required for regulation of telomere length and chromosome end protection (16). TEN1, like STN1, is regulated by NMD through its 5′-UTR sequences (9), but high levels of TEN1 alone do not affect telomere length. To determine whether Ten1p contributes to the senescence delay in NMD mutants, we constructed a strain containing a high-copy plasmid in which the TEN1 promoter sequences were replaced with PGAL1. In contrast to the est2Δ PGAL1-STN1 strain, tlc1Δ YEP PGAL1-TEN1 upf2Δ strain demonstrated a delay in senescence that was similar to the telomerase-deficient upf mutants (Table 5). Thus, NMD regulation of TEN1 mRNA levels alone does not affect the rate of senescence in telomerase-deficient strains.

TEN1 and STN1 function together in telomere capping. Furthermore, extra TEN1 enhances the short-telomere phenotype associated with extra Stn1p (9, 16). Therefore, we asked whether higher levels of Stn1p together with extra copies of TEN1 would affect the rate of senescence more than higher levels of Stn1p alone. For this experiment, TEN1 was expressed from YEP-TEN1, which contains only the portion of the TEN1 promoter that is not subject to NMD regulation (M. McClellan, unpublished data), while STN1 was expressed from PGAL1-STN1. Interestingly, est2Δ cells expressing increased levels of both STN1 and TEN1 together exhibited no upf-dependent change in the rate of senescence. Thus, increasing the levels of both STN1 and TEN1 mRNAs is sufficient to phenocopy the upf delayed-senescence phenotype and can explain how the NMD pathway affects the rate of senescence in telomerase-deficient strains.

CDC13 effects on senescence are independent of NMD.

CDC13, along with STN1 and TEN1, is a component of the telomere cap that is important for telomere maintenance. It recruits telomerase and regulates telomere access to telomerase (4, 14, 39). The cdc13-2 allele was isolated in the same genetic screen that isolated strains carrying mutations in EST1, EST2, and EST3 (29). Like the other est mutants, cdc13-2 mutants have short telomeres and undergo senescence (29). However, unlike the est1, -2, and -3 alleles isolated, the cdc13-2 allele retains some residual telomerase activity in vivo and senesces more slowly than other est mutants (29). Furthermore, Cdc13-2p does not interact with Stn1p by two-hybrid analysis (4). To determine if the duration of senescence in cdc13-2 strains is affected by loss of the NMD pathway, we constructed and sporulated the appropriate heterozygous diploids and monitored the senescence of cdc13-2 upf2Δ spores in serial liquid culture passages. We found that cdc13-2 strains, like upfΔ estΔ and upfΔ tlc1Δ strains, senesced after ∼80 PDs. However, unlike the other telomerase-deficient strains, the difference in the timing of senescence between the cdc13-2 and cdc13-2 upf2Δ strains was not significant (Table 2), indicating that senescence of cdc13-2 mutants is not delayed by loss of the NMD pathway. This is likely due to the fact that Cdc13 mRNA levels are not regulated by NMD (9) and the lack of interaction between Cdc13-2p and Stn1p (4). Thus, alterations in the structure of the telomere cap protein Cdc13p, like alterations in the amount of the telomere cap protein, Stn1p, regulate the rate of senescence in telomerase-deficient cells.

DISCUSSION

Cells that lack telomerase components undergo replicative senescence resulting in a reduction of proliferative potential. The NMD pathway accelerates senescence in otherwise wild-type cells that lack either telomerase holoenzyme components (TLC1 and Est2p) or accessory factors (Est1p and Est3p). Loss of the NMD pathway causes a delay in the senescence process such that telomerase-deficient upfΔ strains live for ∼10 to 25 PDs longer than UPF+ strains. As in wild-type telomerase-deficient cells, senescence in upfΔ strains is accompanied by gradual erosion of telomeric DNA and culminates in crisis.

The extension of proliferative potential in upfΔ strains involves neither accelerated survivor formation nor RAD52. Yet, as with wild-type strains, survivors arise eventually in later passages of upfΔ telomerase-deficient strains. This supports the idea that survivor formation is not due to a stochastic process that occurs continuously. Rather, the RAD52-dependent activities that give rise to survivors are induced at a critical point in the senescence process. Interestingly, in upfΔ strains, type I survivors are more prevalent, while type II survivors appear with less frequency (data not shown). Furthermore, the delay of senescence in the telomerase-deficient upfΔ mutants is not due to the MEC3-dependent telomere checkpoint.

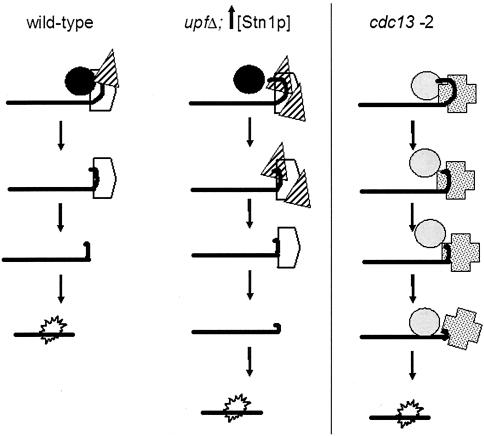

STN1 and TEN1 mRNA levels are regulated by NMD through their 5′-UTR sequences; upfΔ strains have elevated levels of STN1 and TEN1 mRNAs (28). Increased levels of STN1 and TEN1 expression contribute to the short-telomere phenotype of upfΔ in telomerase-proficient cells (30). Increased levels of STN1 and TEN1 also phenocopy most of the senescence delay seen in upfΔ strains (Table 5), indicating that upfΔ-mediated senescence delay is primarily due to changes in the telomere cap structure. We propose that the extended proliferative potential of telomerase-deficient upfΔ strains is caused by a reinforcement of the telomere cap structure when extra Stn1p is available (Fig. 4). We propose that excess Stn1p strengthens the telomere cap and thus protects the chromosome ends from degradation in telomerase-deficient cells. In cells with active telomerase, extra copies of STN1 may result in shorter telomeres (9, 30), because the reinforced telomere cap reduces the access of telomerase to the telomeres (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Model for the role of the telomere cap in senescence in telomerase-deficient cells. The three columns represent three states: wild-type, increased Stn1p levels, and cdc13-2 strains. The top row in each case indicates the situation in the presence of telomerase. The second row illustrates the situation after the loss of telomerase, and subsequent rows indicate events occurring with increasing PDs. Black and gray circles represent telomerase, striped triangles represent Stn1p, and open pentagons and dotted crosses represent Cdc13p.

Increased expression of TEN1 alone had no effect on senescence rates (Table 5). Similarly, extra TEN1 had little effect on telomere length or telomeric silencing phenotypes associated with upfΔ mutations (9). This is consistent with previous reports that found, in contrast to excess STN1, excess TEN1 had no effect on the suppression of cdc13-1 temperature sensitivity or on the negative regulation of telomere length (9, 16). However, as in other situations (9, 16, 30), increased TEN1 expression enhanced the effect of extra STN1 expression.

Cdc13p is a component of the telomere cap that recruits telomerase to the telomere (12, 14, 23). cdc13-2 was isolated as an est mutant (est4) (29, 35). However, cdc13-2 strains senesce more slowly than tlc1Δ, est1Δ, est2Δ, and est3Δ strains, and in cdc13-2 strains, the rate of senescence is not affected by the NMD pathway. This suggests that the telomere cap structure in cdc13-2 mutants is different from that in the other telomerase-deficient (estΔ and tlc1Δ) mutants. The presence of similar rates of senescence in cdc13-2 and upf2Δ strains is consistent with the idea that these mutations delay senescence by altering the telomere cap structure. For upfΔ mutants, the cap is altered by increasing levels of Stn1p, which, we propose, also limits access of telomerase and senescence activities to the telomere (Fig. 4). cdc13-2 alters the cap in a different way that makes it insensitive to upf mutations and to levels of Stn1p. Alternatively, because Cdc13p has multiple roles at the telomere, it could affect senescence independent of its role as a telomere cap component.

One function of the telomere cap is to preserve the chromosome ends from degradation. The rate of senescence is influenced by the initial telomere length at the time that cells lose telomerase: strains with shorter telomeres progress through senescence more rapidly than those with initially longer telomeres. Furthermore, telomerase-deficient upfΔ strains with shorter telomeres, due to upfΔ/upfΔ parents or to high levels of Stn1p in the parent strains, senesce more rapidly than telomerase-deficient upfΔ strains with wild-type telomere length. Our results support the assumption that telomere length is a critical factor in determining a cell's proliferative potential. However, it is important to note that the NMD pathway does not affect the rate of senescence by affecting telomere length: telomerase-deficient upfΔ cells have average telomere lengths that, at the time of crisis, appear to be shorter than the average telomere lengths in otherwise wild-type telomerase-deficient cells. Because the telomeric cap components bind telomeric G-overhang structures (3), we cannot rule out the possibility that strains with altered cap proteins may also have altered G-overhang structures. Nonetheless, telomere cap structure, rather than telomere length alone, is an important contributor to the rate of senescence.

Based on our results, it is appealing to consider the idea that increasing telomere end protection may facilitate the modulation of life span in other organisms. This is consistent with the observation that overexpression of mammalian TRF2 protects shortened telomeres and delays senescence (25). In most human cells, telomerase is not active. Cultured cells exhibit replicative senescence partially due to limited telomerase activity (reviewed in reference 54). Much remains unknown, however, about life span and replicative senescence in whole organisms.

An intriguing connection between telomeres and the NMD pathway was recently revealed in humans. KIAA0732 (hEST1A)was identified by two groups as being a human homologue of Est1p (40, 46). Overexpression of KIAA0732 (hEST1A) caused end-to-end chromosome fusions (40) and altered telomere length (46). At the same time, KIAA0732 was also shown to be similar to SMG5/7a, Caenorhabditis elegans genes involved in the NMD pathway. KIAA0732 (hSmg5/7a) copurifies with Upf1p, Upf2p, and Upf3p and may target a protein phosphatase 2A to Upf1p (7). The mechanisms by which NMD affects telomere functions and the role of KIAA0732 in human cell life span remain to determined.

One approach to extending life span or combating the ill effects of replicative senescence is to reactivate telomerase. A reasonable criticism of this approach is that telomerase activation may be a barrier to cellular immortalization, which would be lost and therefore may lead to an increased risk of carcinogenesis (19, 38), although several experiments have suggested that telomerase activation alone does not increase the occurrence of cancers in mice (5, 41). Our results suggest an alternative approach to increasing life span, without generating immortal cells, by reinforcing the telomere cap structure through increased expression of a cap binding protein. Reinforcing the telomere end structure does not activate telomerase, and at least in yeast, upfΔ tlc1Δ cells appear normal for ∼20 additional PDs and then undergo crisis in an apparently normal manner that produces rare survivor cells. It has been assumed that in the absence of new telomere synthesis, telomeres would erode during each cell cycle, and thus cell life span would be determined by telomere length. An alternative mechanism to extend cellular replicative potential may be to alter the chromosome end protection complex stoichiometry or structure.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Carbonneau, B. Futcher, A. Jacobson, P. Kaufman, and V. Lundblad for yeast strains and plasmids; Mark McClellan for technical assistence with TEN1 promoter regulation; and Jeff Dahlseid, Michael Culbertson, David Kirkpatrick, Neal Lue, Munira Basrai, and members of the Berman laboratory for many helpful discussions.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM 38626 (J.B.) and F32 GM 63352 (L.G.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Blackburn, E. H. 2000. Telomere states and cell fates. Nature 408:53-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodnar, A. G., M. Ouellette, M. Frolkis, S. E. Holt, C. P. Chiu, G. B. Morin, C. B. Harley, J. W. Shay, S. Lichtsteiner, and W. E. Wright. 1998. Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells. Science 279:349-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cervantes, R. B., and V. Lundblad. 2002. Mechanisms of chromosome-end protection. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14:351-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandra, A., T. R. Hughes, C. I. Nugent, and V. Lundblad. 2001. Cdc13 both positively and negatively regulates telomere replication. Genes Dev. 15:404-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, S., C. Khoo, and R. A. DePinho. 2001. Modeling chromosomal instability and epithelial carcinogenesis in the telomerase-deficient mouse. Semin. Cancer Biol. 11:227-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, Q., A. Ijpma, and C. W. Greider. 2001. Two survivor pathways that allow growth in the absence of telomerase are generated by distinct telomere recombination events. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1819-1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiu, S. Y., G. Serin, O. Ohara, and L. E. Maquat. 2003. Characterization of human Smg5/7a: a protein with similarities to Caenorhabditis elegans SMG5 and SMG7 that functions in the dephosphorylation of Upf1. RNA 9:77-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Culbertson, M. R. 1999. RNA surveillance. Unforeseen consequences for gene expression, inherited genetic disorders and cancer. Trends Genet. 15:74-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahlseid, J. N., J. Lew-Smith, M. J. Lelivelt, S. Enomoto, A. Ford, M. Desruisseaux, M. McClellan, N. Lue, M. R. Culbertson, and J. G. Berman. 2002. mRNAs encoding telomerase components and regulators are controlled by the UPF genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 2:134-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DuBois, M. L., Z. W. Haimberger, M. W. McIntosh, and D. E. Gottschling. 2002. A quantitative assay for telomere protection in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 161:995-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enomoto, S., L. Glowczewski, and J. Berman. 2002. MEC3, MEC1, and DDC2 are essential components of a telomere checkpoint pathway required for cell cycle arrest during senescence in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:2626-2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans, S. K., and V. Lundblad. 1999. Est1 and Cdc13 as comediators of telomerase access. Science 286:117-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Game, J. C., and P. D. Kaufman. 1999. Role of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromatin assembly factor-I in repair of ultraviolet radiation damage in vivo. Genetics 151:485-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grandin, N., C. Damon, and M. Charbonneau. 2000. Cdc13 cooperates with the yeast Ku proteins and Stn1 to regulate telomerase recruitment. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8397-8408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grandin, N., C. Damon, and M. Charbonneau. 2001. Cdc13 prevents telomere uncapping and Rad50-dependent homologous recombination. EMBO J. 20:6127-6139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grandin, N., C. Damon, and M. Charbonneau. 2001. Ten1 functions in telomere end protection and length regulation in association with Stn1 and Cdc13. EMBO J. 20:1173-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grandin, N., S. I. Reed, and M. Charbonneau. 1997. Stn1, a new Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein, is implicated in telomere size regulation in association with Cdc13. Genes Dev. 11:512-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greider, C. W. 1993. Telomerase and telomere-length regulation: lessons from small eukaryotes to mammals. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 58:719-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrington, L., and M. O. Robinson. 2002. Telomere dysfunction: multiple paths to the same end. Oncogene 21:592-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayflick, L. 1997. Mortality and immortality at the cellular level. A review. Biochemistry (Moscow) 62:1180-1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He, F., and A. Jacobson. 2001. Upf1p, Nmd2p, and Upf3p regulate the decapping and exonucleolytic degradation of both nonsense-containing mRNAs and wild-type mRNAs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1515-1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hughes, T. R., S. K. Evans, R. G. Weilbaecher, and V. Lundblad. 2000. The Est3 protein is a subunit of yeast telomerase. Curr. Biol. 10:809-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes, T. R., D. K. Morris, A. Salinger, N. Walcott, C. I. Nugent, and V. Lundblad. 1997. The role of the EST genes in yeast telomere replication. CIBA Found. Symp. 211:41-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson, F. B., R. A. Marciniak, M. McVey, S. A. Stewart, W. C. Hahn, and L. Guarente. 2001. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae WRN homolog Sgs1p participates in telomere maintenance in cells lacking telomerase. EMBO J. 20:905-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karlseder, J., A. Smogorzewska, and T. de Lange. 2002. Senescence induced by altered telomere state, not telomere loss. Science 295:2446-2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiyono, T., S. A. Foster, J. I. Koop, J. K. McDougall, D. A. Galloway, and A. J. Klingelhutz. 1998. Both Rb/p16INK4a inactivation and telomerase activity are required to immortalize human epithelial cells. Nature 396:84-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le, S., J. K. Moore, J. E. Haber, and C. W. Greider. 1999. RAD50 and RAD51 define two pathways that collaborate to maintain telomeres in the absence of telomerase. Genetics 152:143-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lelivelt, M. J., and M. R. Culbertson. 1999. Yeast Upf proteins required for RNA surveillance affect global expression of the yeast transcriptome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:6710-6719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lendvay, T. S., D. K. Morris, J. Sah, B. Balasubramanian, and V. Lundblad. 1996. Senescence mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with a defect in telomere replication identify three additional EST genes. Genetics 144:1399-1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lew, J. E., S. Enomoto, and J. Berman. 1998. Telomere length regulation and telomeric chromatin require the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:6121-6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin, J. J., and V. A. Zakian. 1995. An in vitro assay for Saccharomyces telomerase requires EST1. Cell 81:1127-1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lingner, J., T. R. Cech, T. R. Hughes, and V. Lundblad. 1997. Three ever shorter telomere (EST) genes are dispensable for in vitro yeast telomerase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:11190-11195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowell, J. E., A. I. Roughton, V. Lundblad, and L. Pillus. 2003. Telomerase-independent proliferation is influenced by cell type in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 164:909-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lundblad, V., and E. H. Blackburn. 1993. An alternative pathway for yeast telomere maintenance rescues est1− senescence. Cell 73:347-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lustig, A. J. 2001. Cdc13 subcomplexes regulate multiple telomere functions. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:297-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nugent, C. I., T. R. Hughes, N. F. Lue, and V. Lundblad. 1996. Cdc13p: a single-strand telomeric DNA-binding protein with a dual role in yeast telomere maintenance. Science 274:249-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oulton, R., and L. Harrington. 2000. Telomeres, telomerase, and cancer: life on the edge of genomic stability. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 12:74-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pennock, E., K. Buckley, and V. Lundblad. 2001. Cdc13 delivers separate complexes to the telomere for end protection and replication. Cell 104:387-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reichenbach, P., M. Hoss, C. M. Azzalin, M. Nabholz, P. Bucher, and J. Lingner. 2003. A human homolog of yeast est1 associates with telomerase and uncaps chromosome ends when overexpressed. Curr. Biol. 13:568-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Samper, E., J. M. Flores, and M. A. Blasco. 2001. Restoration of telomerase activity rescues chromosomal instability and premature aging in Terc−/− mice with short telomeres. EMBO Rep. 2:800-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sherman, F. 1991. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 194:3-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherman, F., and J. Hicks. 1991. Micromanipulation and dissection of asci. Methods Enzymol. 194:21-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singer, M. S., and D. E. Gottschling. 1994. TLC1: template RNA component of Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomerase. Science 266:404-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Snedecor, G. W., and W. G. Cochran. 1980. Statistical methods, 7th ed. Iowa State University Press, Ames.

- 46.Snow, B. E., N. Erdmann, J. Cruickshank, H. Goldman, R. M. Gill, M. O. Robinson, and L. Harrington. 2003. Functional conservation of the telomerase protein est1p in humans. Curr. Biol. 13:698-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steiner, B. R., K. Hidaka, and B. Futcher. 1996. Association of the Est1 protein with telomerase activity in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:2817-2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stone, E. M., C. Reifsnyder, M. McVey, B. Gazo, and L. Pillus. 2000. Two classes of sir3 mutants enhance the sir1 mutant mating defect and abolish telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 155:509-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teng, S. C., C. Epstein, Y. L. Tsai, H. W. Cheng, H. L. Chen, and J. J. Lin. 2002. Induction of global stress response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells lacking telomerase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 291:714-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teng, S.-C., and V. A. Zakian. 1999. Telomere-telomere recombination is an efficient bypass pathway for telomere maintenance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:8083-8093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vaziri, H., and S. Benchimol. 1998. Reconstitution of telomerase activity in normal human cells leads to elongation of telomeres and extended replicative life span. Curr. Biol. 8:279-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang, J., L. Y. Xie, S. Allan, D. Beach, and G. J. Hannon. 1998. Myc activates telomerase. Genes Dev. 12:1769-1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang, M. J., Y. C. Lin, T. L. Pang, J. M. Lee, C. C. Chou, and J. J. Lin. 2000. Telomere-binding and Stn1p-interacting activities are required for the essential function of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cdc13p. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:4733-4741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weng, N. P., and R. J. Hodes. 2000. The role of telomerase expression and telomere length maintenance in human and mouse. J. Clin. Immunol. 20:257-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou, J., K. Hidaka, and B. Futcher. 2000. The Est1 subunit of yeast telomerase binds the Tlc1 telomerase RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:1947-1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]