Abstract

Purpose

A subset of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) who are predicted to have lower-risk disease as defined by the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) demonstrate more aggressive disease and shorter overall survival than expected. The identification of patients with greater-than-predicted prognostic risk could influence the selection of therapy and improve the care of patients with lower-risk MDS.

Patients and Methods

We performed an independent validation of the MD Anderson Lower-Risk Prognostic Scoring System (LR-PSS) in a cohort of 288 patients with low- or intermediate-1 IPSS risk MDS and examined bone marrow samples from these patients for mutations in 22 genes, including SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1, and DNMT3A.

Results

The LR-PSS successfully stratified patients with lower-risk MDS into three risk categories with significant differences in overall survival (20% in category 1 with median of 5.19 years [95% CI, 3.01 to 10.34 years], 56% in category 2 with median of 2.65 years [95% CI, 2.18 to 3.30 years], and 25% in category 3 with median of 1.11 years [95% CI, 0.82 to 1.51 years]), thus validating this prognostic model. Mutations were identified in 71% of all samples, and mutations associated with a poor prognosis were enriched in the highest-risk LR-PSS category. Mutations of EZH2, RUNX1, TP53, and ASXL1 were associated with shorter overall survival independent of the LR-PSS. Only EZH2 mutations retained prognostic significance in a multivariable model that included LR-PSS and other mutations (hazard ratio, 2.90; 95% CI, 1.85 to 4.52).

Conclusion

Combining the LR-PSS and EZH2 mutation status identifies 29% of patients with lower-risk MDS with a worse-than-expected prognosis. These patients may benefit from earlier initiation of disease-modifying therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Accurate determination of prognosis is critical for selection of appropriate therapy in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). At the time of diagnosis, the majority of patients with MDS (approximately 70%) have lower-risk disease as defined by the low- and intermediate-1 risk groups of the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS).1 Despite the prediction of a relatively benign clinical course, a subset of these patients with lower-risk MDS have more aggressive disease and shorter overall survival. Although higher-risk patients with MDS (IPSS intermediate-2 or high-risk groups) are typically treated with hypomethylating agents or considered for allogeneic stem-cell transplantation, lower-risk patients are usually offered less aggressive therapies, including hematopoietic growth factors, transfusion support, or simply active observation without treatment.2 The ability to recognize patients from this IPSS-defined lower-risk subset with a worse prognosis than expected could have important implications for the selection of risk-appropriate therapy while improving prognostic accuracy and informing MDS biology.

Prognostic models could be improved by developing a predictor specifically for patients with lower-risk MDS that is based on clinical parameters. Investigators at the MD Anderson Cancer Center have proposed such a prognostic model that more finely stratifies the predicted overall survival of patients with MDS with lower IPSS risk, although this model has not been confirmed in an independent cohort. This Lower-Risk Prognostic Scoring System (LR-PSS) considers many of the same risk factors as the IPSS, including cytogenetic abnormalities, the proportion of blasts in the bone marrow, and the presence of specific cytopenias, albeit with modifications to the thresholds and relative weights of different parameters (Table 1). Specifically, although the IPSS treats all patients with a platelet count less than 100 × 109/L equally, the LR-PSS assigns added risk to patients with more severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 50 × 109/L), while decreasing the prognostic impact of excess blasts.3–5 Unlike the IPSS, the LR-PSS assigns a specific prognostic weight to the patient's age and stratifies patients into three risk categories instead of the two IPSS groups that define patients with lower risk.

Table 1.

Lower-Risk Prognostic Scoring System (LR-PSS)

| Clinical Variables | Points |

|---|---|

| Unfavorable cytogenetics (not normal or del(5q) alone) | 1 |

| Age ≥ 60 years | 2 |

| Hemoglobin < 10 g/dL | 1 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | |

| < 50 | 2 |

| 50-200 | 1 |

| Bone marrow blasts ≥ 4% | 1 |

| Risk group assignment (total points) | |

| Category 1 | 0-2 |

| Category 2 | 3-4 |

| Category 3 | 5-7 |

Another approach to improve the prediction of prognosis in lower-risk MDS is to integrate molecular features by including mutation status for critical disease genes. Neither the IPSS nor the LR-PSS includes the mutation status of any genes. We have shown that several of the recurrent somatic mutations seen in MDS predict prognosis independent of the IPSS score.6 A subset of these mutations is associated with thrombocytopenia, an important parameter in the LR-PSS, raising the possibility that the LR-PSS may capture the consequences of key mutations, thereby obviating the need for genetic analysis to determine prognosis in lower-risk MDS. Alternatively, mutations may alter the biology of MDS cells in a way that is not captured by clinical parameters, demonstrating that the determination of mutation status for specific genes is critical for the evaluation and treatment of lower-risk MDS.

To establish the role of mutations in predicting prognosis for lower-risk MDS, we calculated the LR-PSS and determined the mutation status of 22 genes in a cohort of 288 patients with lower-risk MDS. In addition to the 18 genes we had previously characterized in these samples, we examined the mutational status of DNMT3A and the three most frequently mutated splicing factor genes (SF3B1, SRSF2, and U2AF1), which were recently reported to be recurrently mutated in MDS.7–10 With this information, we validated the LR-PSS in an independent cohort of patients with lower-risk MDS. We demonstrated that specific mutations can be associated with prognostic clinical features and overall survival in this cohort. To the best of our knowledge, we have performed the first multivariable analysis to include DNMT3A, SF3B1, SRSF2, and U2AF1 mutations and have shown how consideration of mutation status might influence the prediction of prognosis in both the IPSS and the LR-PSS.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Sample Cohort

We previously characterized a cohort of 439 clinically annotated samples from patients with MDS for mutations in 18 genes.6 Within this cohort, 299 samples were from patients with IPSS low- or intermediate-1 risk (10 of which were missing data required to calculate the LR-PSS, and one of which was excluded for being a member of the original cohort used to define the LR-PSS). We therefore included 288 samples from patients with lower-IPSS-risk MDS in this study (Data Supplement). The median follow-up for patients was 4.5 years (95% CI, 4.1 to 7.30 years).

DNA Sequencing

Samples of whole bone marrow mononuclear cell–derived DNA from the 288 patients with MDS in this study were examined for mutations in 18 oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes (TET2, ASXL1, RUNX1, EZH2, JAK2, NRAS, TP53, ETV6, CBL, NPM1, IDH1, IDH2, KRAS, BRAF, PTEN, CDKN2A, GNAS, PTPN11), as reported previously.6 In this study, we sequenced exons 12 to 16 of SF3B1 (NM_012433.2), exon 1 of SRSF2 (NM_003016.4), exons 2 and 6 of U2AF1 (NM_001025203), and the entire coding region of DNMT3A (NM_175629.1) in all samples by using the Sanger technique (Beckman Coulter Genomics, Danvers, MA). Variants previously reported as somatic were included in further analyses; remaining variants listed as germline polymorphisms in the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism database (dbSNP build 132), reported as germline in other studies, or present in matched buccal swab DNA (available for 140 samples [49%]) were excluded.

Statistical Methods

Overall survival was calculated from the time of sample collection to the time of death from any cause. The 15 mutations with a frequency ≥ 1% were evaluated along with age (< 60 v ≥ 60 years), sex, and either IPSS or LR-PSS (excluding age) as candidates in stepwise Cox regression modeling. P values were two sided and considered significant if less than .05 for outcome measures and ≤ .01 for the association of mutations with clinical characteristics. Additional statistical methods are delineated in the Data Supplement.

RESULTS

Validation of the LR-PSS

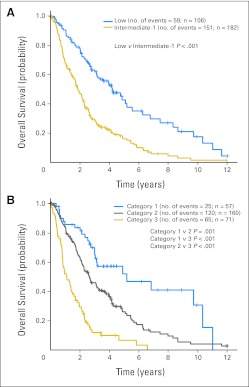

We first evaluated clinical parameters that might improve the prediction of prognosis in patients with MDS who had lower-risk disease, as determined by the IPSS score. The LR-PSS was developed for this purpose in a cohort of 856 patients, but it has not been validated in an independent cohort of patients. We applied the LR-PSS to a well-annotated cohort of 288 patients with low- or intermediate-1 IPSS risk MDS, and clinical characteristics representative of patients with lower-risk MDS were described in epidemiologic studies (Data Supplement).6,11,12 When the LR-PSS was applied to this cohort, 57 patients (19.8%) were assigned to risk category 1, with a median survival of 5.19 years (95% CI, 3.01 to 10.34 years); 160 (55.6%) were assigned to category 2, with a median survival of 2.65 years (95% CI, 2.18 to 3.30 years); and 71 (24.7%) were assigned to category 3, with a median survival of 1.11 years (95% CI, 0.82 to 1.51 years, Fig 1; Data Supplement).

Fig 1.

(A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for 288 patients with low and intermediate-1 International Prognostic Scoring System risk. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the same patients assigned to categories 1 to 3 by the MD Anderson Lower-Risk Prognostic Scoring System. Overall survival was calculated from the time of sample collection to the time of death from any cause.

The differences in overall survival between LR-PSS categories for patients in our cohort were highly significant (P ≤ .001 for each comparison) and were comparable to those in the original description of the LR-PSS (6.7, 2.3, and 1.2 years in categories 1, 2, and 3, respectively).13 The outcome for patients assigned to category 3 is similar to the published median survival of patients with intermediate-2 IPSS risk MDS, indicating that these patients should be considered for therapies commonly reserved for higher-risk MDS.1 These findings validate the LR-PSS in an independent cohort of patients.13

Genetic Characterization of Lower-IPSS-Risk MDS

Mutations of individual genes can provide prognostic information that is independent of the IPSS score in patients with MDS generally, but the prognostic significance of mutations has not been examined specifically in patients with lower-risk MDS. Bone marrow aspirates from the 288 patients in our cohort were previously examined for mutations in 18 genes, including TET2, ASXL1, TP53, RUNX1, EZH2, ETV6, and NRAS. Following recent reports of mutations in DNMT3A, SF3B1, SRSF2, and U2AF1 in MDS, we sequenced the recurrently mutated regions of these genes in all samples.

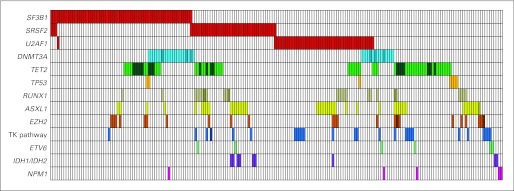

The most commonly mutated genes in lower-risk MDS were TET2 (23% of samples), SF3B1 (22%), U2AF1 (16%), ASXL1 (15%), SRSF2 (15%), and DNMT3A (13%). In aggregate, we identified mutations in 204 of 288 samples from patients with lower-risk MDS (71% of the cohort), including 70% of patients with a normal karyotype. The distribution and co-occurrence of mutations is shown in Figure 2.

Fig 2.

Distribution of mutations in 204 of 288 samples from patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes with one or more mutations. Each column represents an individual sample. Colored cells indicate a mutation in the gene(s) described in that row on the left. Darker bars indicate two or more distinct mutations. Tyrosine kinase (TK) pathway genes include NRAS, KRAS, BRAF, CBL, and JAK2.

DNMT3A and SF3B1 Mutations Commonly Co-Occur

Mutations in DNMT3A and SF3B1 were not exclusive of mutations in any of the other frequently mutated genes, but they co-occurred with each other significantly more often than predicted by chance (P < .001), suggesting a previously unappreciated molecular synergy between these two genetic lesions. Specifically, of the 36 patients with a DNMT3A mutation, 20 (56%) also had a mutation in SF3B1. As previously reported, mutations of SF3B1 were highly enriched in samples from patients with refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts, present in 78% of patients v 13% of patients without refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts (P < .001).8,14

Mutated Genes Associated With Prognostic Features

Mutations may alter clinical parameters in a manner that is accurately captured by the LR-PSS. Alternatively, some mutations may yield orthogonal information about the MDS phenotype that is not well captured by standard clinical variables. To address these possibilities, we examined the association of mutations with the clinical parameters included in the LR-PSS. Advanced age was associated with the presence of one or more mutations (48% < 60 years v 77% ≥ 60 years; P ≤ .001), but no individual gene mutation was significantly associated with age. Mutations of ASXL1, RUNX1, and EZH2 were associated with a hemoglobin level less than 10 g/dL (P ≤ .008 for each comparison). A bone marrow blast count of 4% or greater was associated with mutations in SRSF2, ASXL1, RUNX1, NRAS, and CBL (P < .005 for each comparison), and mutations in U2AF1, ASXL1, RUNX1, and NRAS were associated with a platelet count of less than 50 × 109/L (P < .01 for each comparison). In contrast, SF3B1 mutation was associated with a normal or increased platelet count (4% with < 50 × 109/L v 15% with 50 to 200 × 109/L v 51% with > 200 × 109/L; P < .001).

These findings demonstrate that mutations are significantly associated with specific parameters that are used to calculate the LR-PSS. We therefore examined whether the mutations associated with higher-risk features are disproportionately represented in the higher-risk LR-PSS categories. Indeed, patients with mutations in ASXL1, U2AF1, SRSF2, RUNX1, NRAS, and CBL were over-represented in the highest-risk LR-PSS category (P ≤ .005 for each comparison; Data Supplement). In contrast, patients with SF3B1 mutations, which were not associated with prognostically adverse clinical measures, were significantly under-represented in category 3 (P < .001). These findings demonstrate the association of mutations with prognostic clinical variables and suggest that the LR-PSS may more accurately capture biology driven by particular mutations.

Mutated Genes Associated With Differences in Overall Survival

We next examined the association of mutation status with overall survival in our lower-risk MDS cohort. In univariate analyses, mutations of ASXL1, RUNX1, EZH2, SRSF2, U2AF1, and NRAS were associated with shorter overall survival; hazard ratios (HRs) are provided in Table 2 and survival curves are provided in the Data Supplement. Only mutations of SF3B1 showed a nonsignificant trend toward longer survival (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.54 to 1.07; P = .12).

Table 2.

Univariate and Adjusted HRs Associated With Mutations in 15 Genes

| Mutation Type | Patients (n = 288) |

Univariate HR | 95% CI | P | IPSS Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P | LR-PSS Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | ||||||||||

| TET2 | 65 | 23 | 1.35 | 0.97 to 1.86 | .073 | 1.28 | 0.92 to 1.77 | .14 | 1.05 | 0.75 to 1.46 | .78 |

| SF3B1 | 64 | 22 | 0.76 | 0.55 to 1.07 | .12 | 0.80 | 0.57 to 1.12 | .19 | 0.98 | 0.69 to 1.39 | .89 |

| ASXL1 | 43 | 15 | 2.06 | 1.44 to 2.94 | < .001 | 1.88 | 1.31 to 2.69 | < .001 | 1.56 | 1.08 to 2.26 | .019 |

| U2AF1 | 46 | 16 | 1.49 | 1.05 to 2.11 | .027 | 1.46 | 1.03 to 2.08 | .034 | 1.20 | 0.84 to 1.72 | .31 |

| SRSF2 | 42 | 13 | 1.54 | 1.08 to 2.18 | .017 | 1.35 | 0.94 to 1.93 | .10 | 1.37 | 0.96 to 1.96 | .08 |

| DNMT3A | 36 | 13 | 1.03 | 0.66 to 1.61 | .89 | 1.07 | 0.69 to 1.66 | .77 | 1.12 | 0.72 to 1.76 | .61 |

| RUNX1 | 25 | 9 | 2.43 | 1.58 to 3.74 | < .001 | 2.26 | 1.47 to 3.49 | < .001 | 1.67 | 1.07 to 2.61 | .024 |

| EZH2 | 23 | 8 | 3.10 | 1.99 to 4.83 | < .001 | 3.36 | 2.15 to 5.25 | < .001 | 2.90 | 1.85 to 4.52 | < .001 |

| JAK2 | 9 | 3 | 1.75 | 0.89 to 3.43 | .10 | 1.31 | 0.67 to 2.58 | .44 | 1.54 | 0.78 to 3.02 | .21 |

| NRAS | 8 | 3 | 3.42 | 1.68 to 6.98 | < .001 | 2.60 | 1.27 to 5.32 | .009 | 1.60 | 0.76 to 3.35 | .22 |

| TP53 | 7 | 2 | 2.24 | 0.99 to 5.09 | .054 | 2.43 | 1.07 to 5.52 | .034 | 2.63 | 1.16 to 5.99 | .021 |

| ETV6 | 6 | 2 | 1.28 | 0.47 to 3.44 | .63 | 1.18 | 0.44 to 3.19 | .74 | 0.76 | 0.28 to 2.07 | .59 |

| CBL | 5 | 2 | 1.88 | 0.77 to 4.60 | .17 | 1.43 | 0.58 to 3.50 | .44 | 0.85 | 0.34 to 2.12 | .73 |

| NPM1 | 5 | 2 | 2.38 | 0.88 to 6.46 | .089 | 1.83 | 0.67 to 4.99 | .24 | 2.08 | 0.77 to 5.67 | .15 |

| IDH1 | 5 | 2 | 1.07 | 0.44 to 2.60 | .89 | 0.74 | 0.30 to 1.81 | .50 | 1.00 | 0.41 to 2.44 | .99 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; IPSS, International Prognostic Scoring System; LR-PSS, Lower-Risk Prognostic Scoring System.

We next examined whether mutations predict prognosis after adjusting for the LR-PSS. The prognostic significance for most of the mutated genes was less marked after adjusting for LR-PSS risk category, indicating that the clinical parameters incorporated into the LR-PSS capture some of the prognostic significance of point mutations (Table 2). The adjusted HRs fell to 1.56 (95% CI, 1.08 to 2.26) for ASXL1 mutations and 1.67 (95% CI, 1.07 to 2.61) for RUNX1 mutations. Mutations of NRAS, U2AF1, and SRSF2 were no longer significant after adjusting for the LR-PSS. Mutations of TP53 predicted a shorter overall survival after adjusting for either the IPSS (HR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.07 to 5.52) or the LR-PSS (HR, 2.63; 95% CI, 1.16 to 5.99) but were rare in this cohort of patients with lower-risk MDS (n = 7). Importantly, EZH2 mutations remained a powerful and significant predictor of overall survival after adjustment for LR-PSS risk categories (HR, 2.90; 95% CI, 1.85 to 4.52).

Since a significant portion of the predictive power of mutations is captured by the LR-PSS, we performed a stepwise multivariable Cox regression analysis to identify mutations that contribute significantly to the prediction of overall survival in addition to existing prognostic scoring systems and would therefore be the most useful to analyze clinically. We first examined the IPSS, considering patient age (< 60 v ≥ 60 years), sex, IPSS risk group, and the mutation status of each of the 15 genes mutated in more than 1% of patients as candidate variables in the model (Table 3). In addition to age and IPSS risk group, mutations of EZH2, NRAS, and ASXL1 were each independently associated with a higher risk of death in this model. Overall, 21% of patients carried one or more mutations in these genes, indicating that more than one fifth of patients categorized as having lower-risk MDS by the IPSS have mutations associated with worse prognosis.

Table 3.

Multivariable Overall Survival Models for IPSS and LR-PSS

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model I (IPSS, age, sex, and mutation status) | |||

| IPSS risk classification | |||

| Intermediate-1 v low | 2.28 | 1.67 to 3.12 | < .001 |

| Age ≥ 60 v < 60 years | 1.61 | 1.09 to 2.37 | .017 |

| Mutational status | |||

| EZH2 present v absent | 2.93 | 1.84 to 4.67 | < .001 |

| NRAS present v absent | 2.56 | 1.24 to 5.29 | .011 |

| ASXL1 present v absent | 1.60 | 1.10 to 2.34 | .014 |

| Model II (LR-PSS, sex, and mutation status) | |||

| LR-PSS classification | |||

| Category 2 v 1 | 1.98 | 1.28 to 3.06 | .002 |

| Category 3 v 1 | 4.92 | 3.05 to 7.93 | < .001 |

| Mutational status | |||

| EZH2 present v absent | 2.90 | 1.85 to 4.52 | < .001 |

NOTE. Cox proportional hazard regression models were constructed for individual mutation status and adjusted for the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS; Model I) and Lower-Risk Prognostic Scoring System (LR-PSS; Model II) risk classifications. The 15 mutations with a frequency ≥ 1% were evaluated along with age (< 60 v ≥ 60 years), sex, and either IPSS or LR-PSS (excluding age) as candidates in stepwise Cox regression modeling. Patient sex was not a statistically significant variable in either model.

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

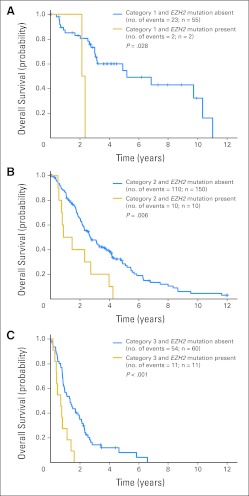

In a similar model considering the LR-PSS risk categories in place of age and the IPSS risk groups, only EZH2 mutations remained as a significant predictor of shorter overall survival (HR, 2.90; 95% CI, 1.85 to 4.52; Fig 3) in addition to LR-PSS risk group. This analysis demonstrates that the LR-PSS considers clinical features that capture much of the prognostic information linked with gene mutations associated with a shorter overall survival. Nevertheless, mutations in EZH2 are highly significant predictors of overall survival, with an HR of ≥ 2.84 in all models, and the impact of EZH2 mutations is not captured by either the IPSS or LR-PSS. Genetic analysis of EZH2 would therefore significantly improve prediction of prognosis in lower-risk MDS.

Fig 3.

Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves for patients with myelodysplastic syndromes in each Lower-Risk Prognostic Scoring System (LR-PSS) risk category stratified by EZH2 mutation status. (A) Category 1 patients; (B) category 2 patients; (C) category 3 patients.

DISCUSSION

MDS is a heterogeneous condition, and patients have highly variable clinical courses. The accurate determination of prognosis is particularly critical for the selection of appropriate therapy for patients with lower-risk MDS. We analyzed clinical and molecular parameters in a cohort of 288 patients with lower-risk IPSS MDS, validated the MD Anderson LR-PSS (designed to more finely stratify IPSS low- and intermediate-1-risk patients on the basis of clinical features), and demonstrated the value of integrating additional genetic information into this calculation. We confirmed that mutations in certain genes are associated with disease subtypes, differences in overall survival, and clinical features. In a multivariable analysis, mutations in the EZH2 gene were found to be significantly associated with a shorter overall survival independent of the LR-PSS and mutations in other genes. By combining patients with either EZH2 mutations or LR-PSS category 3 risk, 29% of patients with lower-IPSS-risk MDS could be identified with shorter-than-expected overall survival—a group that could be considered for more aggressive initial therapy.

The LR-PSS was developed by incorporating clinical information not present in the IPSS to stratify patients with lower-risk MDS more accurately, but it had not been previously independently validated. Specifically, the LR-PSS considers features missing from the IPSS, such as patient age, and reweights others, including thrombocytopenia, anemia, and blast count (Data Supplement). The LR-PSS divides patients into three risk categories instead of the two IPSS lower-risk categories, allowing for greater stratification between those in the highest- and lowest-risk groups. Applying the LR-PSS to our lower-risk MDS cohort, 25% of patients were assigned to risk category 3. Patients in this risk category have a median survival equivalent to that of patients in the higher-risk intermediate-2 IPSS risk group, a group that is typically considered for more aggressive therapy.15

Neither the LR-PSS, the IPSS, nor any other published prognostic MDS model considers somatic mutations as prognostic criteria, although mutations are key drivers of disease phenotype.16,17 Given the overlap between clinical features and genetic lesions, the argument could be made that molecular abnormalities should be the principal way in which disease prognosis is determined. Indeed, we found that mutations in any of four genes (ASXL1, RUNX1, TP53, and EZH2) present in 25% of patients carried independent prognostic information after adjusting for LR-PSS risk categories, demonstrating the value of considering genetic information to improve the determination of prognosis. However, clinical variables are likely to contribute prognostic information that cannot be captured by molecular analysis alone, such as the contribution of comorbidities, disease kinetics, and marrow microenvironmental factors to mortality risk. A combination of clinical and molecular factors is likely needed to most accurately define prognosis. In particular, prognostic molecular abnormalities that do not have readily evident clinical manifestations are the most important to consider. For example, EZH2 mutations were strongly associated with a poor prognosis (median survival, 0.81 years; 95% CI, 0.55 to 1.46 years; Data Supplement) in patients assigned to category 2 or 3 but were not tightly linked to clinical features. Although mutations in ASXL1, RUNX1, TP53, and EZH2 each carried prognostic information independent of the LR-PSS, only EZH2 mutations remained as significant independent predictors of poor outcome in a final model obtained from stepwise Cox regression analysis of patients stratified by the LR-PSS and the mutation status of 14 other genes.

In our study, mutations of DNMT3A were not associated with a poor prognosis in contrast to findings from a smaller study in MDS.7 A potential explanation for this discrepancy is that our study was focused on lower-risk MDS. Molecularly, our cohort was enriched in patients with mutations in SF3B1. Indeed, we discovered that DNMT3A and SF3B1 mutations overlapped more often than expected by chance, indicating possible biologic cooperativity between these pathogenic lesions. Since SF3B1 mutations had a trend toward longer survival, co-occurrence of these two somatic disease alleles may have mitigated any negative effect of DNMT3A mutations on survival in this lower-risk cohort. Indeed, patients with DNMT3A and SF3B1 mutations had a longer median survival than patients with DNMT3A mutations alone (median, 4.16 years [95% CI, 2.11 to 6.85] v 1.45 years [95% CI, 0.59 to 2.74 years]; P = .035) as shown in the Data Supplement.

Determining an accurate prognosis is critical for the care and treatment of patients with MDS. Once the full spectrum of somatic mutations in MDS has been defined, optimal prognostic scoring systems will need to include relevant molecular features. We have shown that consideration of mutations in several genes can refine the prognosis of patients with MDS compared with the IPSS alone. Prognosis can also be effectively determined in those with low- or intermediate-1 IPSS risk by using the LR-PSS plus the addition of testing for EZH2 mutations, thereby identifying 29% of patients with lower-risk MDS who might benefit from more aggressive therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Laura MacConaill, Sarah Kehoe, Charles Hatton, Emanuele Palescandolo, Adriana Heguy, Randall MacAuley, Bernd Boidol, and Marie McConkey for assistance with genetic analyses; Tim Graubert and Matt Walter for their helpful advice; and the Cure for Cancer Foundation for support of the Tissue Repository.

Footnotes

Supported by Grants No. R0101DK087992, R01 HL082945, and P01 CA108631 from the National Institutes of Health, by the Starr Cancer Consortium, and by the Burroughs-Wellcome Fund (Career Awards for Medical Scientists; B.L.E.), and Grant No. 3K12 CA087723 from the National Institutes of Health (R.B.).

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Rafael Bejar, Genoptix (C); Benjamin L. Ebert, Celgene (C), Genoptix (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: None Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Rafael Bejar, David P. Steensma, Donna Neuberg, Guillermo Garcia-Manero, Benjamin L. Ebert

Provision of study materials or patients: Naomi Galili, Azra Raza, Hagop Kantarjian, Guillermo Garcia-Manero

Collection and assembly of data: Rafael Bejar, Kristen E. Stevenson, Bennett A. Caughey, Omar Abdel-Wahab, Naomi Galili, Azra Raza, Hagop Kantarjian, Ross L. Levine, Guillermo Garcia-Manero

Data analysis and interpretation: Rafael Bejar, Kristen E. Stevenson, Bennett A. Caughey, Omar Abdel-Wahab, David P. Steensma, Hagop Kantarjian, Donna Neuberg, Guillermo Garcia-Manero, Benjamin L. Ebert

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, et al. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 1997;89:2079–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cutler CS, Lee SJ, Greenberg P, et al. A decision analysis of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for the myelodysplastic syndromes: Delayed transplantation for low-risk myelodysplasia is associated with improved outcome. Blood. 2004;104:579–585. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer SR, Tefferi A, Hanson CA, et al. Platelet count is an IPSS-independent risk factor predicting survival in refractory anaemia with ringed sideroblasts. Br J Haematol. 2008;140:722–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantarjian H, Giles F, List A, et al. The incidence and impact of thrombocytopenia in myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer. 2007;109:1705–1714. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schanz J, Steidl C, Fonatsch C, et al. Coalesced multicentric analysis of 2,351 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes indicates an underestimation of poor-risk cytogenetics of myelodysplastic syndromes in the International Prognostic Scoring System. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1963–1970. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bejar R, Stevenson K, Abdel-Wahab O, et al. Clinical effect of point mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2496–2506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walter MJ, Ding L, Shen D, et al. Recurrent DNMT3A mutations in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2011;25:1153–1158. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papaemmanuil E, Cazzola M, Boultwood J, et al. Somatic SF3B1 mutation in myelodysplasia with ring sideroblasts. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1384–1395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshida K, Sanada M, Shiraishi Y, et al. Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature. 2011;478:64–69. doi: 10.1038/nature10496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graubert TA, Shen D, Ding L, et al. Recurrent mutations in the U2AF1 splicing factor in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Genet. 2012;44:53–57. doi: 10.1038/ng.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sekeres MA. The epidemiology of myelodysplastic syndromes. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2010;24:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sekeres MA, Schoonen WM, Kantarjian H, et al. Characteristics of US patients with myelodysplastic syndromes: Results of six cross-sectional physician surveys. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1542–1551. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Manero G, Shan J, Faderl S, et al. A prognostic score for patients with lower risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia. 2008;22:538–543. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malcovati L, Papaemmanuil E, Bowen DT, et al. Clinical significance of SF3B1 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes and myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2011;118:6239–6246. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg PL, Attar E, Bennett JM, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Myelodysplastic syndromes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9:30–56. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2011.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kantarjian H, O'Brien S, Ravandi F, et al. Proposal for a new risk model in myelodysplastic syndrome that accounts for events not considered in the original International Prognostic Scoring System. Cancer. 2008;113:1351–1361. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komrokji RS, Corrales-Yepez M, Al Ali N, et al. Validation of the MD Anderson Prognostic Risk Model for patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer. 2011;118:2659–2664. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.