Abstract

Adult neurogenesis arises from neural stem cells within specialized niches1–3. Neuronal activity and experience, presumably acting upon this local niche, regulate multiple stages of adult neurogenesis, from neural progenitor proliferation to new neuron maturation, synaptic integration and survival1, 3. Whether local neuronal circuitry has a direct impact on adult neural stem cells is unknown. Here we show that in the adult hippocampus nestin-expressing radial glia-like quiescent neural stem cells4–9 (RGLs) respond tonically to the neurotransmitter GABA via γ2 subunit-containing GABAA Rs. Clonal analysis9 of individual RGLs revealed a rapid exit from quiescence and enhanced symmetric self-renewal after conditional γ2 deletion. RGLs are in close proximity to GAD67+ terminals of parvalbumin-expressing (PV+) interneurons and respond tonically to GABA released from these neurons. Functionally, optogenetic control of dentate PV+, but not somatostatin- or vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)-expressing, interneuron activity can dictate the RGL choice between quiescence and activation. Furthermore, PV+ interneuron activation restores RGL quiescence following social isolation, an experience that induces RGL activation and symmetric division8. Our study identifies a niche cell-signal-receptor trio and a local circuitry mechanism that control the activation and self-renewal mode of quiescent adult neural stem cells in response to neuronal activity and experience.

Recent genetic lineage-tracing studies have identified nestin-expressing RGLs as quiescent neural stem cells (qNSCs) in the adult mouse hippocampus4–9. In adult nestin-GFP mice10, GFP+ cells in the subgranular zone (SGZ) with radial processes expressed GFAP, but rarely MCM2, indicating quiescence (Supplementary Fig. 1 a–b). To assess whether local interneurons directly regulate adult qNSCs via neurotransmitter release, we examined RGL responses to GABA in slices acutely prepared from adult nestin-GFP mice by electrophysiology. GFP+ RGLs recorded under whole-cell voltage-clamp exhibited prominent responses to GABA (200 mM) or GABAAR agonist muscimol (200 mM), which were abolished by the GABAAR agonist bicuculline (BMI; 50 μM; Supplementary Fig. 1 c–d). Interestingly, GABA responses were potentiated by diazepam (1 μM), which specifically enhances γ2-containing GABAAR responses to GABA11. Indeed, GFP+ RGLs exhibited γ2 immunoreactivity (Supplementary Fig. 1e). γ2-containing GABAARs are present in non neuronal cells and can be found both outside and inside of synapses in mature neurons11. No spontaneous or evoked synaptic currents in response to field stimulation of the dentate granule cell layer were detected in GFP+ RGLs (n = 25 cells; Supplementary Fig. 1 f–g). Instead, tonic GABA responses were recorded (n = 18 cells; Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1 g–h), suggesting GABA spill-over from nearby synapses11. To exclude the possibility of GABAergic synaptic inputs with low release probabilities, we applied hypertonic solution to enhance presynaptic release12. Increased tonic responses, but not synaptic currents, were observed (Supplementary Fig. 1h). Inhibition of GABA reuptake transporter GAT1 with NO-711 (10 μM) also increased tonic responses (Fig. 1), further supporting the tonic nature of GABAergic responses in RGLs.

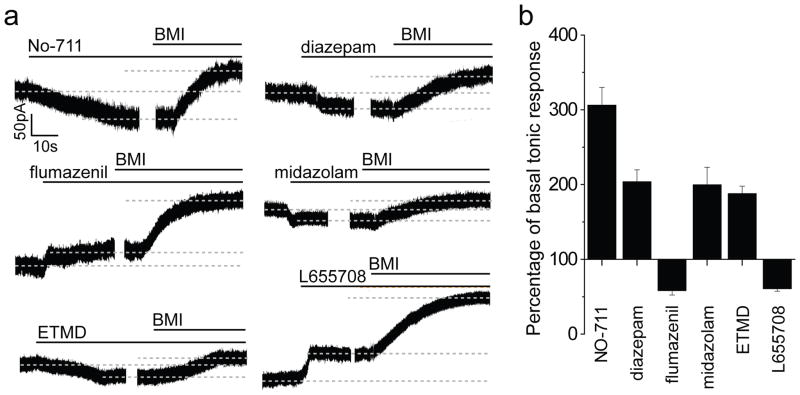

Figure 1. Tonic activation of adult quiescent neural stem cells by GABA via α5β3γ2 GABAARs.

a, Sample traces of whole-cell voltage-clamp recording from GFP+ RGLs with treatment of diazepam (1 μM), flumazenil (10 μM), midazolam (10 μM), ETMD (100 nM), or L-655708 (50 μM), followed by BMI (100 μM) to obtain baseline for normalizing tonic responses for each cell. b, Summary of normalized amplitude of tonic response. Values represent mean ± s.e.m. (n = 4–5 cells; all significantly different from the basal condition; P < 0.05; student t-test).

We next explored pharmacological properties of tonic GABAergic responses in RGLs13. Consistent with the γ2 involvement, diazepam (1 μM) significantly increased, while the benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil (10 μM) decreased tonic responses (Fig. 1). The α5-selective benzodiazepine agonist midazolam (10 μM), or the β3-selective positive allosteric modulator etomidate (ETMD; 100 nM), increased tonic GABA responses, whereas the α5-selective inverse agonist L-655708 (50 μM) decreased this response (Fig. 1). Together, these results suggest that α5β3 γ2 GABAARs are present in adult dentate RGLs to mediate tonic responses to GABA.

To examine the functional role of GABA in regulating adult dentate RGLs in vivo, we assessed EdU incorporation and MCM2 expression by RGLs after diazepam treatment (Supplementary Fig. 2a). We identified RGLs as SGZ cells with nestin+ radial processes (Fig. 2a). Stereological quantification showed that diazepam treatment led to a 45% decrease in the number of EdU+ RGLs compared to vehicle treatment (Fig. 2b). The number of MCM2+nestin+ RGLs and the percentage of RGLs that were MCM2+ were also significantly decreased (Fig. 2b). Thus, systemic enhancement of γ2-mediated GABA signalling promotes adult dentate RGL quiescence at the population level.

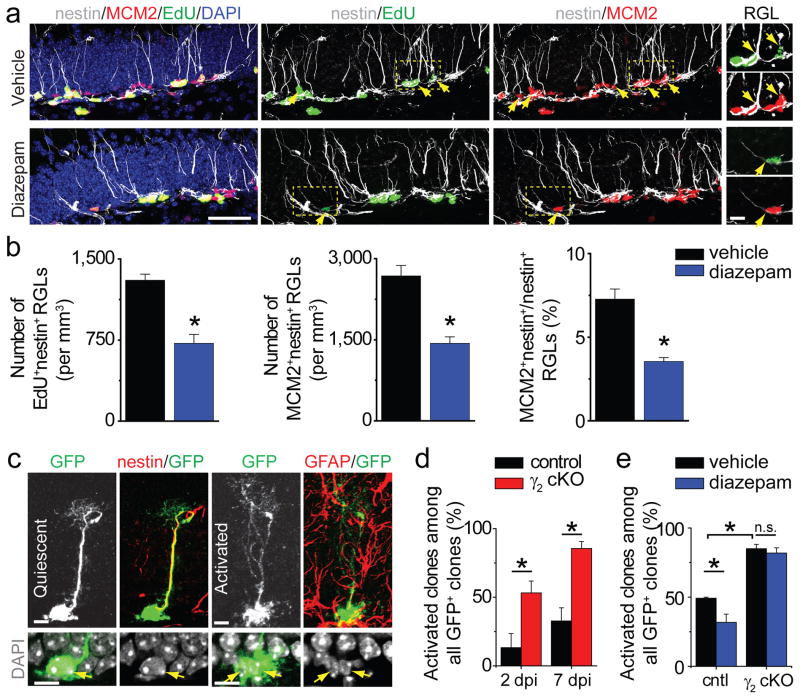

Figure 2. Cell autonomous role of γ2-containing GABAARs in maintaining adult neural stem cell quiescence.

a–b, Diazepam promotes quiescence of nestin+ RGLs in the adult dentate gyrus. Shown in (a) are sample confocal images of immunostaining of nestin, MCM2, EdU and DAPI. Arrows point to nestin+MCM2+ or nestin+EdU+ RGLs. Scale bars: 50 μm (left) and 10 μm (last column). Shown in (b) are summaries of stereological quantification of RGL EdU incorporation and MCM2 expression. Values represent mean ± s.e.m. (n = 4 animals; *: P < 0.01; student t-test). c–e, γ2 deletion in individual RGLs leads to their activation. Shown in (c) are sample confocal images of immunostaining. Scale bars: 10 μm. Also shown are summaries of percentages of RGL clones that were activated (d) and those with vehicle or diazepam treatment at 7 dpi (e) for control (cntl) and cKO mice. Values represent mean ± s.e.m. (n = 4–8 animals; *: P < 0.01; n.s.: P > 0.1; student t-test).

To examine a cell autonomous role of γ2 in RGLs, we generated nestin-CreERT2+/−; Z/EGf/−;γ2f/f (cKO) mice and nestin-CreERT2+/−; Z/EGf/−;γ2+/+ (control) mice and we used a low dose of tamoxifen for sparse induction to perform clonal analysis of adult RGLs9 (Supplementary Fig. 2 b–d). Immunohistology and electrophysiology indicated highly efficient but not complete γ2 deletion (Supplementary Fig. 2 e–f). In cKO mice, the percentage of RGL clones that were activated dramatically increased compared to control mice at 2 and 7 days post induction (dpi; Fig. 2c–d). Diazepam treatment decreased the percentage of activated RGL clones in control mice at 7 dpi, but had no effect in cKO mice (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 2g). These results demonstrated a direct role of GABA in maintaining adult NSC quiescence via γ2 signalling.

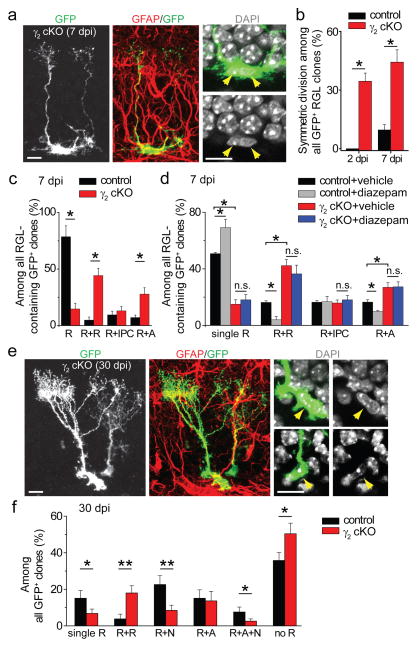

We next examined the fate choice of activated RGLs. There was a marked increase in pairs of closely associated GFP+ RGLs at 2 dpi in adult cKO mice compared to controls, indicating increased RGL symmetric self-renewal (Fig. 3a–b). Detailed analysis at 7 dpi showed increased symmetric and astrogliogenic asymmetric RGL division in cKO mice (Fig. 3c). Conversely, diazepam treatment decreased RGL symmetric division and astrogliogenic asymmetric division in control mice, but had no effect in cKO mice (Fig. 3d). In supporting short-term lineage-tracing results, analysis of clonal composition at 30 dpi showed decreased percentages of quiescent clones and increased percentage of clones with multiple RGLs in cKO mice (Fig. 3e–f and Supplementary Fig. 3). Consistent with a role of GABA signalling in promoting new neuron survival14, percentages of neurogenic clones and multi-lineage clones were significantly reduced (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 3e). In contrast, clones without any RGLs were increased in cKO mice (Fig. 3f), suggesting increased RGL depletion after γ2 deletion. Together, these gain- and loss-of-function analyses identified GABA as a niche signal to maintain adult NSC quiescence and inhibit symmetric self-renewal and astrocyte fate choice via γ2-containing GABAARs under basal physiological conditions.

Figure 3. Clonal analysis of RGL fate choice after conditional γ2 deletion in individual RGLs in the adult dentate gyrus.

a–d, Short-term effect of γ2 deletion on the activation and fate choice of adult dentate RGLs. Shown in (a) are sample confocal images of immunostaining for a GFP+ clone indicating symmetric division. Scale bars: 10 μm. Also shown are summaries of percentages of clones indicating symmetric divisions (b), percentages of different types of RGL clones at 7 dpi (c) and those with vehicle or diazepam treatment (d): R+R (2 RGLs), R+IPC (one RGL and one GFAP- IPC), and R+A (one RGL and one GFAP+ bushy astrocyte). Values represent mean ± s.e.m. (n = 4–8 animals; *: P < 0.05; n.s.: P > 0.1; student t-test). e–f, Long-term effect of γ2 deletion on the composition of GFP+ clones in the adult dentate gyrus. Shown in (e) are sample confocal images of immunostaining for a clone consisting of two GFAP+ cells with radial processes. Scale bars: 10 μm. Shown in (f) is a summary of percentages of different clone types among all GFP+ clones at 30 dpi: R: RGL; N: IPC/neuron; A: astrocyte. Values represent mean + s.e.m. (n = 4–8 animals; *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01; student t-test).

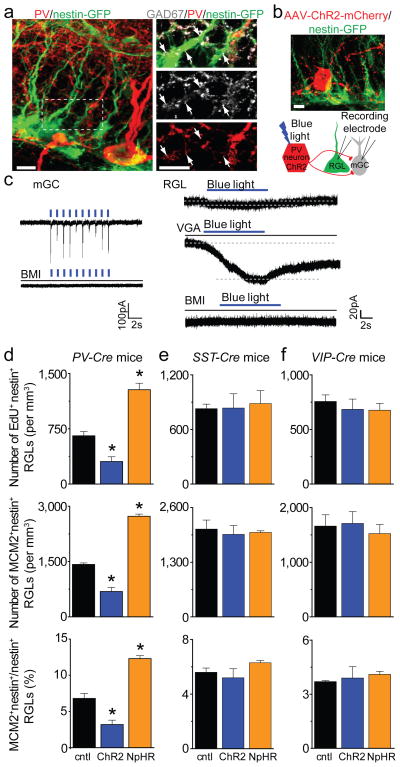

We next sought to identify GABA-releasing niche cells among multiple interneuron subtypes in the adult dentate gyrus15, 16. Immunohistological analysis of adult nestin-GFP mice showed a close association between GFP+ RGLs and GAD67+ terminals from PV+ interneurons (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Movie 1). To determine whether PV+ interneurons functionally interact with RGLs, we took an optogenetic approach and used double floxed (DIO) adeno-associated virus (AAV) to express channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) or halorhodopsin (eNpHR3.0) specifically in PV+ interneurons using adult PV-Cre mice17 (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Immunostaining and electrophysiology confirmed the specificity and efficacy of AAV-mediated opsin expression in controlling dentate PV+ interneuron firing (Supplementary Fig. 4 b–e). In acute slices from PV-Cre+/−; nestin-GFP+/− mice, photo-activation of PV+ interneurons induced resulted in GABAergic synaptic responses in mature granule cells and, importantly, tonic responses in GFP+ RGLs (Fig. 4b–c). Furthermore, decrease of GABA turnover with the GABA transaminase inhibitor vigabatrin (VGA; 100 μM) drastically increased GFP+ RGL responses to PV+ interneuron activation (Fig. 4c). Together, these results indicate that adult RGLs respond tonically to GABA released from PV+ interneurons.

Figure 4. Regulation of quiescence and activation state of neural stem cells by PV+, but not SST+ or VIP+ interneuron activity in the adult dentate gyrus.

a, Sample confocal images of GFP and immunostaining of PV and GAD67 (See Supplementary Movie 1). Scale bars: 5 μm. b, Sample confocal image and schematic diagram of electrophysiological recording. Scale bar: 10 μm. c, Sample whole-cell voltage-clamp recording traces of responses upon light stimulation of ChR2+PV+ interneurons from a mature granule cell (mGC; 1 Hz) and a GFP+ RGL (8 Hz) in acute slices, and with treatment of bicuculline (BMI; 50 μM), or vigabatrin (VGA; 100 μM). d–f, Regulation of RGL activation in the adult dentate gyrus by local interneuron activity. Shown are summaries of stereological quantification of RGL EdU incorporation and MCM2 expression upon in vivo activation (ChR2) or suppression (NpHR) of PV+ (d), SST+ (e) or VIP+ (f) interneurons or sham treatment (cntl; see Supplementary Fig. 5a and 6e for experimental paradigms). Values represent mean ± s.e.m. (n = 3–4 animals; *: P < 0.01; student t-test).

To assess the functional impact of PV+ interneuron activity on RGL behaviour, we photo-activated or suppressed PV+ interneurons in the dentate gyrus of adult PV-Cre mice for 5 days (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Compared to sham treatment without light stimulation, EdU incorporation and MCM2 expression by RGLs were significantly decreased after activation of PV+ interneurons expressing ChR2-YFP, resulting in a 53% reduction of RGL activation at the population level (Fig. 4d and supplementary Fig. 5b). Conversely, suppression of PV+ interneurons expressing eNpHR-YFP led to a 95% increase of RGL activation (Fig. 4d). These results identified PV+ interneurons as a critical niche component and demonstrated that PV+ interneuron activity can dictate the RGL choice between quiescence and activation in the adult dentate gyrus.

Do other subtypes of local interneurons also regulate RGL behaviour in vivo? We developed similar optogenetic strategies to manipulate somatostatin (SST+) or vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP+) interneurons16 (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Both SST+ and VIP+ interneurons exhibited elaborated processes in the SGZ and hilus region (Supplementary Fig. 6 c–d and Supplementary Movie 2) and our paradigm labelled a greater number of SST+ and VIP+ interneurons than PV+ interneurons in the adult dentate gyrus (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Electrophysiological recoding of GFP+ RGLs did not detect any tonic or synaptic responses upon light-induced activation of SST+ or VIP+ interneurons in acute slices (Supplementary Fig. 6 c–d). Functionally, photo-activated or suppressed dentate SST+ or VIP+ interneurons had no effect on EdU incorporation and MCM2 expression by RGLs (Fig. 4e–f and supplementary Fig. 6e). Thus, coupling of neuronal circuit activity to RGL behaviour appears to be distinctive of PV+ interneurons and not broadly across different local interneuron subtypes.

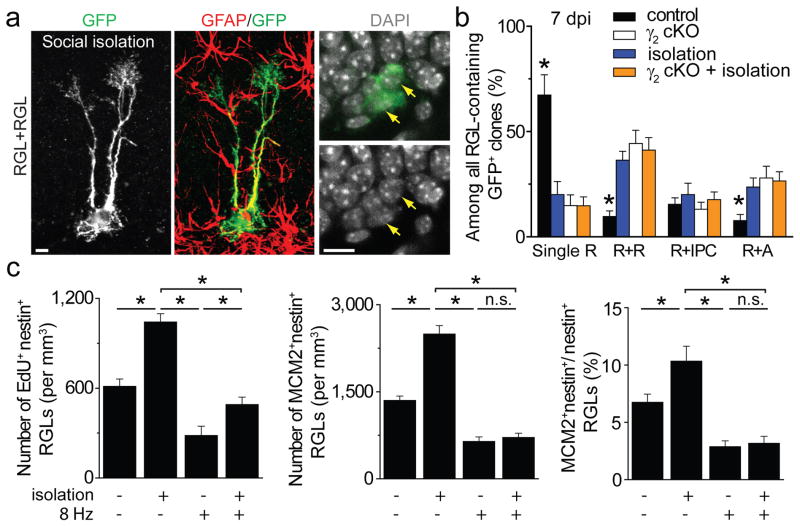

Finally, we assessed whether GABA also serves as a niche signal to mediate experience-dependent regulation of RGLs. We subjected mice to a social isolation paradigm, which decreases neuronal activity in the adult dentate gyrus18 and was recently shown to promote RGL expansion8. Clonal analysis at 7 dpi showed that, compared to group housing, social isolation led to a significant increase in GFP+ RGL activation and symmetric and astrogenic division, similar to γ2 deletion in RGLs (Fig. 5a–b and Supplementary Fig. 7a). Importantly, γ2-deficient RGLs exhibited no additional activation or fate alternation following social isolation (Fig. 5b). At the population level, EdU incorporation and MCM2 expression by RGLs were significantly increased after social isolation (Fig. 5c and supplementary Fig. 7 b–c). Importantly, PV+ interneuron activation abolished the social isolation-induced increase of RGL activation (Fig. 5c). Thus, dentate PV+ interneurons also mediate experience-dependent regulation of adult qNSCs via GABA-γ2 signalling.

Figure 5. Contribution of GABA signalling from PV+ interneurons to experience-dependent regulation of adult quiescent neural stem cells.

a–b, Clonal analysis of RGL fate choice following social isolation. Shown in (a) are sample confocal images of immunostaining for an activated clone with two RGLs at 7 dpi following social isolation (See Supplementary Fig. 7 for experimental paradigm). Scale bars: 10 μm. Shown in (b) is a summary of different types of clones at 7 dpi. Values represent mean ± s.e.m. (n = 4–8 animals; *: P < 0.05; student t-test). c, Summaries of stereological quantification of RGL EdU incorporation and MCM2 expression. Values represent mean ± s.e.m. (n = 4 animals; *: P < 0.05; n.s.: P > 0.1; student t-test).

Precise control of somatic stem cell activity is essential for the long-term maintenance of tissue homeostasis and needs to be closely linked to tissue demands at any given time. Our study of adult RGLs at both clonal and population levels identified a novel niche cell-niche signal-receptor trio that regulates both adult qNSC activation and self-renewal mode in response to neuronal activity and experience (Supplementary Fig. 8). GABA has been shown to decrease proliferation of other stem cells and progenitors in vitro, including mouse embryonic stem cells, via GABAARs, the PI3K-related kinase family and the histone variant H2AX19, 20. Interestingly, PTEN deletion in individual RGLs also leads to activation and symmetric self-renewal in the adult dentate gyrus9, suggesting a conserved mechanism regulating proliferation of various stem cells via the GABAAR and PI3K/PTEN pathway.

Our optogenetic approach identified PV+ interneurons as a critical and unique niche component among different interneuron subtypes that couples neuronal circuit activity to qNSC regulation in vivo under both physiological conditions and in response to specific experience. PV+ interneurons are abundant in the hippocampus and have been implicated in higher brain function and cognitive dysfunction15. In the adult dentate gyrus, PV+ interneurons receive excitatory inputs from dentate granule cells and, to a lesser extent, from entorhinal cortical inputs (Supplementary Fig. 8a). We reconstructed one PV+ interneuron in the adult PV-Cre+/−; nestin-GFP+/− mice and estimated that it covered over 200 GFP+ RGLs in the dentate gyrus (Supplementary Movie 3). A characteristic feature of PV+ interneurons is the formation of ensembles coupled by both electrical (through GAP junctions) and chemical connections (through reciprocal innervations)15. Thus, PV+ interneurons are well suited to couple local circuit activity to the regulation of a large number of adult NSCs in the hippocampus as an adaptive mechanism - increasing qNSC activation when local circuitry activity levels are low, while keeping NSCs in quiescence when activity levels are high (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Given that both the number and properties of hippocampal PV+ interneurons are regulated by physiological and pathological conditions, such as aging, Alzheimer’s diseases, epilepsy, chronic stress, schizophrenia and other severe psychiatric illness21–26, our findings have broad implications.

Methods

Animals, housing, administration of tamoxifen, EdU and AAV, and optogenetic manipulations

The following genetically modified mice and crosses between them were used for electrophysiological analysis: nestin-GFP10 (CB57BL/6 background), PV-Cre17 (JAX laboratory; stock number: 008069; stock name: B6;129P2-Pvalbtm1(cre)Arbr/J), SST-Cre16 (JAX laboratory; stock number: 013044; stock name: Ssttm2.1(cre)Zjh/J), VIP-Cre16 (JAX laboratory, stock number: 010908; stock name: Viptm1(cre)Zjh/J). The following mice were used for neurogenesis analysis: wild-type (C57BL/6), nestin-CreERT2+/−;Z/EG+/−;γ2floxed/floxed (ref27; C57BL/6) and nestin-CreERT2+/−;Z/EG+/− (C57BL/6), PV-Cre (B6;129), SST-Cre (B6;129), and VIP-Cre (B6;129). Animals were housed in a standard 14 hr light/10 hr dark cycle. Socially isolated animals were individually housed right after weaning for at least 6 weeks before tamoxifen or EdU injection, and had free access to food and water8. A single dose of tamoxifen (TMX; 62 mg/kg) was i.p. injected into 6- to 10-week-old mice as previously described9.

For optogenetic manipulations, Cre-dependent recombinant AAV vectors were used based on a DNA cassette carrying two pairs of incompatible loxP sites with the opsin genes (ChR2-H134-mCherry, ChR2-H134-YFP, or eNpHR3.0-YFP) inserted between lox sites in the reverse orientation as described previously17 (Supplementary Fig. 4a). The recombinant AAV vectors were serotyped with AAV2/9 for ChR2 (packaged at the UPenn Vector Core), and AAV9 for eNpHR3.0 (packaged at University of North Carolina Vector Core). The following final viral concentrations were used for AAV viruses (x1012 particles/ml): 7.4 (ChR2-YFP), 36 (ChR2-mCherry), and 8 (eNpHR3.0-YFP), respectively. AAV was stereotaxically delivered into the dentate gyrus using the following coordinates (in mm): anterioposterior = −2 from bregma; lateral = ±1.5; ventral = 2.2. Fiber optic cannulae (Doric Lenses, Inc.) were implanted at the same injection sites right after AAV injection with the dorsal-ventral depth of 1.6 mm from the skull. Animals were then allowed to recover for at least 3 weeks from surgery. For analysis of RGL activation at the population level after optogenetic manipulations, littermates of animals were used and an in vivo light paradigm was administered 8 hrs per day for 5 consecutive days (Supplementary Fig. 5a, 6e and 7b). For ChR2-YFP stimulation, blue light flashes (472 nm; 5 ms at 8 Hz) through the DPSSL laser system (Laser Century Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China) were delivered in vivo every 5 minutes for 30 s/per trial. For eNpHR-YFP stimulation, continuous yellow light (593 nm) was delivered in vivo. On the 5th day, animals were injected with EdU (41.1 mg/kg body weight) 6 times with an interval of 2 hrs. Animals were sacrificed 2 hrs after the last EdU injection and processed for immunostaining as previously described9.

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Electrophysiology

Mice were anaesthetized and processed for slice preparation as previously described28. Briefly, brains were quickly removed into the ice-cold solution (in mM: 110 choline chloride, 2.5 KCl, 1.3 KH2PO4, 25.0 NaHCO3, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgSO4, 20 dextrose, 1.3 sodium L-ascorbate, 0.6 sodium pyruvate, 5.0 kynurenic acid). Slices (300 μm thick) were sectioned using a vibratome (Leica VT1000S) and transferred to a chamber containing the external solution (in mM: 125.0 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.3 KH2PO4, 1.3 MgSO4, 25.0 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 1.3 sodium L-ascorbate, 0.6 sodium pyruvate, 10 dextrose, pH 7.4, 320 mOsm), bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2. Electrophysiological recordings were obtained at 32°C − 34°C. GFP+ RGLs located within the SGZ in adult nestin-GFP+/− mice were visualized by DIC and fluorescence microscopy. A whole-cell patch-clamp configuration was employed in the voltage-clamp mode (Vm = −65 mV) or current-clamp mode. Microelectrodes (4–6 MΩ) were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries and filled with the internal solution containing (in mM)28: 135 CsCl gluconate, 15 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 0.1 EGTA, 10.0 HEPES, 4 ATP (magnesium salt), 0.3 GTP (sodium salt), 7 phosphocreatine (pH 7.4, 300 mOsm). All RGL recordings were carried out in the presence of kynurenic acid (5 mM). Data was collected using an Axon 200B amplifier and acquired with a DigiData 1322A (Axon Instruments) at 10 kHz. For measuring GABA-induced responses from GFP+ RGLs, focal pressure ejection of 200 mM GABA or muscimol through a puffer pipette controlled by a Picospritze (2s puff at 3–5 psi) was used to activate GABAARs under the whole-cell voltage-clamp. A bipolar electrode (World Precision Instruments) was used to stimulate (0.1 ms duration) the dentate granule cell layer. Low frequency (0.1 Hz) and theta bursts (8 Hz with a train of 100 stimuli) were delivered. The stimulus intensity (50 μA) was maintained for all experiments. The following pharmacological agents were used: diazepam (1 μM), NO-711 (10 μM), flumazenil (10 μM), midazolam (10 μM), ETMD (10 μM), L-655708 (50 μM), and vigabatrin (100 μM). All drugs were purchased from Sigma except bicuculline (50 or 100 μM; Tocris).

RGL recordings under optogenetic manipulation in acute brain slices were performed at least 4 weeks after AAV injection. To stimulate ChR2 in labelled interneurons, light flashes (5 ms at 1, 8 or 100 Hz) generated by a Lambda DG-4 plus high-speed optical switch with a 300W Xenon lamp and a 472 nm filter set (Chroma) were delivered to coronal sections through a 40X objective (Carl Zeiss). To stimulate eNpHR in labelled interneurons, continuous yellow light generated by DG-4 plus system with a 593 nm filter set were delivered to coronal sections across a full high-power (40X) field.

Immunohistochemistry, Confocal Imaging, Processing and Quantification

For immunostaining with anti-nestin and anti-MCM2, an antigen retrieval protocol was performed by microwaving sections in boiled citric buffer for 7 minutes as previously described9. For γ2 immunostaining, a weak fixation protocol using live tissues was adopted as previously described30. For characterization of different interneuron subtypes, following antibodies were used: anti-PV (Swant; mouse or rabbit; 1:500), anti-GAD-67 (Millipore; mouse or rabbit; 1:500), ant-SST (Millipore; rat; 1:200), and anti-VIP (Immunostar; rabbit; 1:200). For clonal analysis, coronal brain sections (40 μm) through the entire dentate gyrus were collected in a serial order, and immunostaining was performed using following primary antibodies as previously described9: anti-GFP (Rockland; goat; 1:500), anti-nestin (Aves; chick; 1:500), anti-MCM2 (BD; mouse; 1:500), anti-GFAP (Millipore; mouse or rabbit; 1:1000), anti-PSA-NCAM (Millipore, mouse lgM; 1:500). For quantification of GFP+ clones at 2 and 7 dpi, a single GFP+ RGL was scored as a quiescent clone. Two or more nuclei in a GFP+ RGL clone were scored as activation. Clonal analysis at 30 dpi was carried out exactly as previously described9.

For experiments with diazepam (5 mg/kg body weight; once daily for 5 days), coronal brain sections (40 μm) through the entire dentate gyrus were collected in a serial order. For optogenetic manipulations, sections within a distance of 1.0 mm anterior and 1.0 mm posterior to injection sites were used for quantification, given the estimated light spread in vivo. Immunostaining was performed on every 6th section as previously described9. EdU labelling was performed using Click-iT® EdU Alexa Fluor imaging kit (Invitrogen). Images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal system (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) with a 40X objective using a multi-track configuration. Stereological quantification of cells positive for various molecular markers was assessed in the dentate gyrus using a modified optical fractionator technique29. For quantification of EdU+ or MCM2+ RGLs, an inverted “Y” shape from anti-nestin staining superimposed onto EdU+ or MCM2+ nucleus was scored double positive for nestin and EdU or MCM2. All analyses were performed by investigators blind to experimental conditions. Statistic analysis was performed with student t-test.

For generation of movie files, images were serially reconstructed in Reconstruct (John C. Fiala, the National Institutes of Health), normalized, and deconvolved with Autoquant X2 (Media Cybernetics). Images were then segmented in MATLAB (The Mathworks) using custom code and imported into Imaris (Bitplane). Surface renderings and movies were made using the Surface and Animation functions, respectively, in Imaris (Supplementary Movies 1–3).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. H. Tsai for initial help in the study; members of the Song and Ming laboratories for discussion; H. Davoudi for help, and Q. Hussaini, Y. Cai and L. Liu for technical support. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (NS047344) to H.S., the NIH (NS048271, HD069184), the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression and the Adelson Medical Research Foundation to G.L.M., the NIH (MH089111) to B.L., the NIH (AG040209) and New York State Stem Cell Science and the Ellison Medical Foundation to G.E., and by postdoctoral fellowships from the Life Sciences Research Foundation to J.S. and from the Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund to J.S., C.Z. and K.C.

Footnotes

Author contributions: J.S. led the project and contributed to all aspects. C.Z., M.A.B., G.J.S., D.H., K.C. helped with some experiments; Y.G. and S.G. contributed reagents; J.H. provided SST-Cre mice, G.E. provided nestin-GFP mice; K.D. and K.M. provided initial help on optogenetic tools; B.L. provided γ2f/f mice. J.S., G-l. M and H.S. designed experiments and wrote the paper.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of this article at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Zhao C, Deng W, Gage FH. Mechanisms and functional implications of adult neurogenesis. Cell. 2008;132:645–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kriegstein A, Alvarez-Buylla A. The glial nature of embryonic and adult neural stem cells. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:149–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron. 2011;70:687–702. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seri B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, McEwen BS, Alvarez-Buylla A. Astrocytes give rise to new neurons in the adult mammalian hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7153–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07153.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lagace DC, et al. Dynamic contribution of nestin-expressing stem cells to adult neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12623–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3812-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imayoshi I, et al. Roles of continuous neurogenesis in the structural and functional integrity of the adult forebrain. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1153–61. doi: 10.1038/nn.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Encinas JM, et al. Division-coupled astrocytic differentiation and age-related depletion of neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:566–79. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dranovsky A, et al. Experience dictates stem cell fate in the adult hippocampus. Neuron. 2011;70:908–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonaguidi MA, et al. In vivo clonal analysis reveals self-renewing and multipotent adult neural stem cell characteristics. Cell. 2011;145:1142–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Encinas JM, Vaahtokari A, Enikolopov G. Fluoxetine targets early progenitor cells in the adult brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8233–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601992103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABA(A) receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:215–29. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bekkers JM, Stevens CF. NMDA and non-NMDA receptors are co-localized at individual excitatory synapses in cultured rat hippocampus. Nature. 1989;341:230–3. doi: 10.1038/341230a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caraiscos VB, et al. Tonic inhibition in mouse hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons is mediated by alpha5 subunit-containing gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3662–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307231101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jagasia R, et al. GABA-cAMP response element-binding protein signaling regulates maturation and survival of newly generated neurons in the adult hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2009;29:7966–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1054-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freund TF, Buzsaki G. Interneurons of the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1996;6:347–470. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:4<347::AID-HIPO1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taniguchi H, et al. A resource of Cre driver lines for genetic targeting of GABAergic neurons in cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2011;71:995–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardin JA, et al. Driving fast-spiking cells induces gamma rhythm and controls sensory responses. Nature. 2009;459:663–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ibi D, et al. Social isolation rearing-induced impairment of the hippocampal neurogenesis is associated with deficits in spatial memory and emotion-related behaviors in juvenile mice. J Neurochem. 2008;105:921–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andang M, et al. Histone H2AX-dependent GABA(A) receptor regulation of stem cell proliferation. Nature. 2008;451:460–4. doi: 10.1038/nature06488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernando RN, et al. Cell cycle restriction by histone H2AX limits proliferation of adult neural stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5837–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014993108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lolova I, Davidoff M. Age-related morphological and morphometrical changes in parvalbumin- and calbindin-immunoreactive neurons in the rat hippocampal formation. Mech Ageing Dev. 1992;66:195–211. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(92)90136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Satoh J, Tabira T, Sano M, Nakayama H, Tateishi J. Parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons in the human central nervous system are decreased in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;81:388–95. doi: 10.1007/BF00293459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masiulis I, Yun S, Eisch AJ. The Interesting Interplay Between Interneurons and Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Mol Neurobiol. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s12035-011-8207-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knable MB, Barci BM, Webster MJ, Meador-Woodruff J, Torrey EF. Molecular abnormalities of the hippocampus in severe psychiatric illness: postmortem findings from the Stanley Neuropathology Consortium. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:609–20. 544. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez-Burgos G, Fish KN, Lewis DA. GABA Neuron Alterations, Cortical Circuit Dysfunction and Cognitive Deficits in Schizophrenia. Neural Plast. 2011;2011:723184. doi: 10.1155/2011/723184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andre V, Marescaux C, Nehlig A, Fritschy JM. Alterations of hippocampal GAbaergic system contribute to development of spontaneous recurrent seizures in the rat lithium-pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Hippocampus. 2001;11:452–68. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schweizer C, et al. The gamma 2 subunit of GABA(A) receptors is required for maintenance of receptors at mature synapses. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24:442–50. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ge S, et al. GABA regulates synaptic integration of newly generated neurons in the adult brain. Nature. 2006;439:589–93. doi: 10.1038/nature04404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JY, et al. DISC1 regulates new neuron development in the adult brain via modulation of AKT-mTOR signaling through KIAA1212. Neuron. 2009;63:761–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider Gasser EM, et al. Immunofluorescence in brain sections: simultaneous detection of presynaptic and postsynaptic proteins in identified neurons. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1887–97. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.