Abstract

Introduction

A highly polymorphic T-homopolymer was recently discovered to be associated with late onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) risk and age of onset.

Objective

To explore the effects of the polymorphic polyT tract (rs10524523, referred as ‘523’) on cognitive performance in cognitively healthy elderly.

Methods

181 participants were recruited from local independent-living retirement communities. Informed consent was obtained and participants completed demographic questionnaires, a conventional paper and pencil neuropsychological battery, and the computerized Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB). Saliva samples were collected for determination of the TOMM40 ‘523’ (S, L, VL) and the APOE (ε2, 3, 4) genotypes. From the initial sample of 181 individuals, 127 participants were eligible for the association analysis. Participants were divided into three groups based on ‘523’ genotypes (S/S, S/L-S/VL, and L/L-L/VL-VL/VL) Generalized linear models were used to evaluate the association between the ‘523’ genotypes and neuropsychological test performance. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, education, depression, and APOE ε4 status. A planned sub analysis was undertaken to evaluate the association between ‘523’ genotypes and test performance in a sample restricted to APOE ε3 homozygotes.

Results

The S homozygotes performed better, although not significantly, than the S/L-S/VL and the VL/L-L/VL-VL/VL genotype groups on measures associated with memory (CANTAB Paired-Associate Learning, and VRM Free Recall) and executive function (CANTAB measures of Intra-Extradimensional set shifting). Follow-up analysis of APOEε 3 homozygotes only, showed that the S/S group performed significantly better than the S/VL group on measures of episodic memory (CANTAB Paired-Associate Learning and VRM Free Recall), attention (CANTAB RVP Latency) and executive function (Digit-Symbol substitution). The S/S group performed marginally better than the VL/VL group on Intra-Extradimensional set shifting. None of the associations remained significant after applying a Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

Conclusions

Results suggest important APOE-independent associations between the TOMM40 ‘523’ polymorphism and specific cognitive domains of memory and executive control that are preferentially affected in early stage AD.

Keywords: TOMM40, polyT polymorphism, cognition, aging, neuropsychological tests, CANTAB, Alzheimer’s disease

1. BACKGROUND

The most common form of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is sporadic, late-onset AD (LOAD, age of onset a≥65 years) which accounts for the majority of AD cases. Since the original report, 17 years ago, linking ε4 allele of the Apolipoprotein E gene (APOE ε4) with LOAD [1], APOE ε4 has been the strongest established genetic risk factor for sporadic LOAD. Roses et al. (2009) recently demonstrated that TOMM40, which encodes the essential, mitochondrial protein import translocase (Translocase of the Outer Mitochondrial Membrane, 40kD), and is adjacent to and in linkage disequilibrium with APOE, contributes significantly to the genetic risk and age of onset for LOAD. Using a deep sequencing and phylogenetic analysis approach, it was discovered that the risk locus is a polymorphic polyT tract (rs10524523) positioned within intron 6 of the TOMM40 gene, referred to as ‘523’. The variable ‘523’ polyT lengths are predictive of age of disease onset and risk, and may, in fact, explain much of the effect on age of onset previously attributed to the different APOE alleles[2, 3]. Three major TOMM40 ‘523’ alleles are defined by the length of the T homopolymer: ‘Short’ (S, T≤20), ‘Long’ (L, T=21-29) and ‘Very Long’ (VL, T≥30). The ‘long’ (L) and ‘Very Long’ (VL) alleles are associated with higher LOAD risk and earlier age of disease onset in APOE ε3/4 (~7 years earlier onset in VL/L vs. S/L) [2, 3] and APOE ε3/3 subjects (~9 years earlier onset in VL/VL vs. S/S) [4].

Johnson et al. demonstrated the significant contribution of ‘523’ to impaired cognition in a clinically normal, late middle-aged cohort by comparing verbal memory measures[5]. Specifically, individuals homozygotes for the ‘523’ VL allele and homozygotes for the ‘523’ S allele differed significantly on retrieval from the primacy region of a verbal list learning task, an aspect of episodic memory that is also affected in early AD. Collectively, these studies suggest the importance of ‘523’ in early AD pathogenesis.

The significant contribution of ‘523’ to cognitive decline and age of dementia onset poses an interesting question regarding influence of the ‘523’ on cognitive performance in normal elderly. In the current study we aim to examine the effects of the ‘523’ variant on cognitive function in normal aging. Specifically, we sought to test the hypothesis that the length of the ‘523’ polyT is related to robust cognitive function in old age. The prediction is consistent with that seen in age of LOAD onset, i.e. the shorter length of the T homopolymer (S) may be related to successful cognitive aging into late old age, evidenced by better performance outcomes on neurocognitive tests of episodic memory and executive function that are typically affected in AD, in those homozygous for the S allele as compared to those homozygous for the VL allele.

2. METHODS

2.1.Participants

A total of 181 individuals from five local independent-living retirement communities in the Research Triangle Park region of North Carolina agreed to participate. Participants were recruited from January 2009 to July 2010 by means of IRB-approved advertisements displayed on bulletin boards, fliers, and presentations describing the study. Participants were scheduled for test sessions during which the study was explained and informed consent was obtained. Personal details, including age, education, ethnicity, medication usage, medical history, and family history were collected. The information collected in the personal questionnaire was used also to determine eligibility for the association analyses describe in 2.4. Exclusion criteria included: self-report of neurological disease (including dementia, MCI, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, or TIA), usage of memory medications (e.g. Aricept) or scoring ≤23 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA, see test description on section 2.2.). Neuropsychological tests were administered and saliva samples were collected for genetic analysis. Completion of the entire interview and DNA collection typically took 2 to 3 hours. Procedures were administered by a trained psychometrist in a private designated room at each retirement facility. The project was approved by the Duke Institutional Review Board and followed appropriate ethical protocols.

2.2.Neuropsychological Testing

The neuropsychological battery used in this study was designed to measure selective domains of cognition commonly affected by normal aging of the central nervous system (processing speed, attentional processing, inhibitory control) and AD (episodic memory, particularly verbal learning and memory, spatial learning and memory, complex executive functions, and verbal retrieval/fluency). The complete test battery included selected subtests of the computerized Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB: Cambridge Cognition, UK), conventional paper and pencil neuropsychological tests typically used in the screening and evaluation of memory complaints, and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II)[6]. The computer battery comprised the following tests: paired associates learning (PAL), spatial working memory (SWM), verbal recognition memory - immediate and delayed (VRM), intra-extradimensional set shifting (IED), rapid visual processing (RVP), pattern recognition memory (PRM), spatial span (SSP) and spatial recognition memory (SRM). The test scores were automatically assigned and stored in the CANTAB computers for later extraction. Total scores for each index were included in the analyses.

The conventional neuropsychological battery, presented in paper and pencil format, included: a) a general cognitive screening examination, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)[7]; b) measures of narrative verbal learning and delayed recall (Green’s story recall - immediate and delayed[8]); c) simple visual attention (Trail Making Test Part A; Digit-Symbol Substitution and Symbol Search subtests from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (WAIS-III) [9]); d) visuospatial working memory (Trail Making Test Part B[10, 11]); e) auditory attention (Digit span-forward, a subtest from the WAIS-III[9]); f) auditory working memory (Digit Span backward from the WAIS-III [9]); g) word retrieval including both lexical fluency (Controlled Oral Word Association test (COWA) [12]) and semantic fluency (animal fluency); and h) tests of inhibitory control (Stroop color-word interference[13]). The tests were double scored prior to data entry by trained psychometrists to ensure scoring accuracy.

2.3.Genotyping

Saliva sample collection and DNA extraction were performed using the commercially availableOragene DNA Self-Collection Kit (Oragene) according to the manufacture’s protocol. DNA concentration and the quality of purification were determined spectrophotometrically. APOE genotypes were determined using TaqMan-based allelic discrimination assay (Applied Biosystems). Briefly, APOE ε2/3/4 genotypes were established using two separate SNPs: (1) rs429358 334T/C (ABI assay ID: C_3084793_20), and (2) rs7412 472T/C (ABI assay ID: C_904973_10). The assay was carried out using the ABI 7900HT and genotype analysis was performed by the SNP auto-caller feature of SDS software[14]. APOE genotype assignments were defined as described previously [15]. TOMM40 ‘523’ polyT genotypes were determined based on length variation. The ‘523’ region of each genomic DNA sample was PCR-amplified using a fluorescently labeled primer. Genotypes were determined on an ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer using GeneMapper, version 4.0 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for allelic size assessment. The ‘523’ allele was assigned according to the length of the PCR product[14].

2.4.Data Analysis

Demographic characteristics were compared across genotype groups; continuous variables were assessed with analysis of variance and categorical variables with chi-square statistics. Generalized linear models (GLM) were used to examine the ‘523’ genotypes as predictors of performance of the various neuropsychological tests. Due to the potential for ceiling effects, neuropsychological test scores were transformed prior to analysis. The S-homozygotes (S/S) genotype group was used as the reference group and comparisons were made to the S-heterozygotes (S/L, S/VL) and non-S (L/L, L/VL, VL/VL) groups. Separate GLM models were constructed for each predictor variable of interest. Models were then adjusted for age and other covariates known to influence cognitive performance including APOE status, sex, education, and depression as measured by the BDI. As multiple comparisons were made and the nature of the study was exploratory, we report both corrected and uncorrected p-values for each analysis. Bonferroni corrected p-values by cognitive domain were calculated by dividing an alpha level of 0.05 by the number of tests for each domain. Where multiple scores are listed for the same test, only one test was counted. Because of the strong association between the APOE genotype and cognition in aging, and in order to restrict the analysis to a comparison between S and VL genotypes, we carried out a second stage analysis considering only participants having the APOE ε3/3 genotype and ‘523’ genotypes S/S, S/VL and VL/VL. All analyses were performed using analytical software SAS 9.3.

3. RESULTS

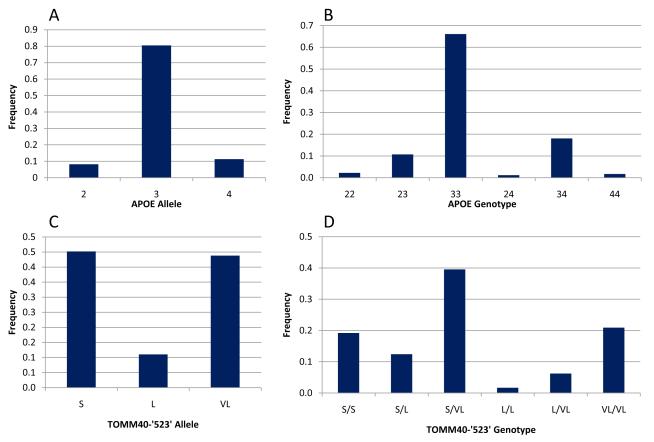

Volunteer participants included 181 elderly between the ages of 64-93 years old. Saliva samples were provided by 180 participants for genotype analysis of the APOE and TOMM40 ‘523’ polymorphisms. Allele and genotype frequencies were determined in the Caucasian group only as this was the majority in the sample. Figure 1 describes the allele frequencies and genotype distributions for APOE (A and B) and TOMM40 ‘523’ (C and D) in the Caucasian participants. The two genes, APOE and TOMM40, physically mapped near each other and are in high linkage disequilibrium (LD). We inferred the APOE backbone (ε 2, 3, 4) of each of the ‘523’ alleles (S, L, VL) in the Caucasian sample. The inferred L allele was primarily linked to ε4, while the majority of the VL and S alleles showed linkage to ε3. These results were consistent with the previous reports [2, 3].

Figure 1.

Genotypes of TOMM40 ‘523’ and APOE were determined using DNA extracted from Saliva samples. APOE genotypes-ε2, 3, 4-were assigned as described previously [15], and TOMM40 ‘523’ genotypes-S, L, VL-were defined based on fragment length polymorphism. Allele and genotypes frequencies were determined for the Caucasian sample (98% of total participants): (A) APOE allele frequencies; (B) APOE genotype frequencies; (C) TOMM40 ‘523’ allele frequencies; (D) TOMM40 ‘523’ genotype frequencies.

We next investigated the association between the neuropsychological battery results and ‘523’ genotypes. 177 of the participants who provided DNA completed successfully the traditional neuropsychological battery; 154 of them also completed the CANTAB. Because educational attainment is known to influence cognitive performance, we set aside scores from individuals (n=7) who failed to report years of education. Visual acuity is similarly an important component of performance on many of the tests. Therefore, in instances where individuals reported vision problems, we set scores to missing on those tests that required vision for adequate performance (i.e., all computerized tests, Trail Making A &B, Digit-Symbol Substitution and Symbol Search subtests from the WAIS-III, the MoCA, and Stroop color-word items for those reporting colorblindness). We also excluded participants who reported neurological problems or neurodegenerative disorders including stroke, TIA, Parkinson’s disease, diagnoses of MCI or dementia (n=25). Finally, we excluded participants who reported taking memory medications (e.g. Aricept) or scored ≤23 on the MoCA[16], retaining a total of 127 participants eligible for these analyses. The characteristics of the analytic sample are shown in Table 1. The sample ranged in age from 64 to 93, was mostly female (68.5%), and highly educated (average 16.8 years of education). The majority of the sample was White and had spoken English as their first language.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics n=127.

| Characteristic | Range | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean(SD) | 64-93 | 80.6 (6.0) |

| Sex, female | 87 (68.5) | |

| Education, mean(SD) | 12-20 | 16.8 (2.3) |

| English as 1st language | 120 (94.5) | |

| Caucasian | 126 (99.2) | |

| APOE | ||

| 0 ε4 alleles | 101 (79.5) | |

| 1 ε4 allele | 25 (19.7) | |

| 2 ε4 alleles | 1 (0.8) | |

| TOMM40 | ||

| SS | 25 (19.7) | |

| S/L, S/VL | 63 (49.6) | |

| L/L, L/VL, VL/VL | 39 (30.7) | |

| MoCA | 27.4 (2.4) | |

| BDI-II | 4.9 (4.1) |

Abbreviations: SD=Standard deviation; MoCA=Montreal Cognitive Assessment; BDI-II=Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd Edition.

Values are number (%) unless indicated as mean (SD).

In order to evaluate the association between performance in neuropsychological tests and ‘523’ genotype, we defined three categories of ‘523’ genotypes: S-homozygotes (S/S; n= 25), S-heterozygotes (S/L, S/VL; n= 63), and non-S (L/L, L/VL, VL/VL; n=39). There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between the groups. Mean test scores, standard deviations, and results of the GLM models comparing genotype groups are shown in Table 2. Test scores tended to be skewed due to generally uniform good performance on all measures. Prior to analysis, scores were transformed by taking either the log, square root, or Tukey transformation of each score in order to normalize the score distributions. Each transformed score was then evaluated to determine if the skew was significant [17]. Scores with non-significant skew were retained for the analysis. Skewed scores, including the Trail Making Test Part A # of errors and CANTAB subscale scores were excluded. The first column in Table 2 lists each test grouped by cognitive domain. The first set of tests listed under each domain are from the paper/pencil battery; the second set are from the CANTAB. In the next three columns, mean scores and standard deviations for each test are listed by genotype group. The p-values from GLM analyses, adjusted for age, sex, education, BDI, and APOE ε4 status (coded as 0 vs. 1 or more ε4 alleles due to the small number of ε4 homozygotes) are listed next for each comparison. The last column lists the Bonferroni corrected p-value threshold for each cognitive domain. The overall p-value for all comparisons was 0.002. Differences were observed between the ‘523’ genotype groups’ mean scores, however, none reached statistical significance at the Bonferroni-corrected p-value level or the p=0.05 level. Differences on the IED were most noticeable, the S/S group had 4 fewer errors than the S/L-S/VL group on IED and 9 fewer errors on IED compared to the L/L-L/VL-VL/VL group. On the PAL, the S/S group had 3 fewer errors on average than the S/L-S/VL group and two fewer than the L/L-L/VL-VL/VL group. Also, the S/S group performed slightly better than the other groups on the VRM (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean scores by group and p-values for Generalized Linear Models of ‘523’ genotypes for n=127 participants’ neuropsychological test scores.

| ‘523’ Genotype Group, Mean (SD) | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Domain Test |

S/S n=25 |

S/VL, S/L n=63 |

VL/VL, L/L, L/VL n=39 |

S/S vs. S/VL, S/L |

S/S vs. VL/VL, L/L, L/VL |

Correcte d p-value threshol d by domain |

| Global Cognition | ||||||

| MoCA | 27.0 (2.3) | 27.4 (2.4) | 27.7 (2.4) | 0.5589 | 0.2916 | 0.05 |

| Memory | ||||||

| Story Recall – Immediate | 46.2 (9.5) | 47.4 (8.9) | 46.2 (8.0) | 0.9896 | 0.5934 | 0.01 |

| Story Recall – Delayed | 33.1 (10.8) | 33.4 (11.6) | 33.0 (9.6) | 0.7606 | 0.6510 | |

| PAL Mean Errors to Success | 6.8 (6.0) | 10.1 (10.7) | 9.1 (7.9) | 0.0907 | 0.2707 | |

| PAL Mean Trials to Success | 3.3 (1.5) | 4.3 (2.9) | 4.1 (2.4) | 0.0736 | 0.1653 | |

| PAL Total Trials | 17.3 (4.0) | 19.7 (6.3) | 19.0 (4.4) | 0.0689 | 0.1486 | |

| PRM Percent Correct | 78.1 (10.1) | 79.2 (8.7) | 79.7 (8.4) | 0.9163 | 0.8022 | |

| PRM Mean Correct Latency | 2462.8 (452.6) | 2559.5 (613.6) | 2786.9 (598.7) | 0.9615 | 0.2145 | |

| SRM Percent Correct | 71.0 (13.5) | 72.8 (10.2) | 68.8 (10.7) | 0.4611 | 0.6686 | |

| SRM Mean Correct Latency | 2974.5 (717.2) | 3018.0 (1184.8) | 3224.9 (931.5) | 0.7331 | 0.8179 | |

| VRM Free Recall Total Correct | 7.7 (3.1) | 5.7 (3.8) | 6.8 (3.4) | 0.0663 | 0.5785 | |

| VRM Recognition Total Correct Less False Positives |

33.5 (2.4) | 31.8 (5.8) | 33.3 (3.9) | 0.4915 | 0.5270 | |

| VRM Free Recall – Immediate Total Correct | 8.5 (2.8) | 7.6 (2.7) | 8.5 (2.7) | 0.2910 | 0.9250 | |

| Attention | ||||||

| # Colors read | 60.7 (10.1) | 63.0 (11.4) | 61.1 (9.0) | 0.2449 | 0.6723 | 0.008 |

| # Words read | 90.7 (13.4) | 92.9 (13.3) | 91.8 (10.4) | 0.2401 | 0.4740 | |

| Forward -# times Correct | 9.9 (1.8) | 9.8 (2.3) | 9.9 (1.8) | 0.8044 | 0.6440 | |

| Trails A seconds | 34.4 (9.6) | 36.7 (11.5) | 37.4 (10.9) | 0.4152 | 0.3382 | |

| RTI 5-choice movement time | 651.1 (149.4) | 626.5 (181.7) | 636.8 (142.9) | 0.5986 | 0.9679 | |

| RTI 5-choice reaction time | 466.7 (73.8) | 493.2 (122.1) | 482.1 (78.5) | 0.4546 | 0.6754 | |

| RVP Probability of a hit | 0.82 (0.1) | 0.77 (0.2) | 0.75 (0.17) | 0.7321 | 0.3849 | |

| RVP Latency | 446.5 (74.3) | 439.87 (77.3) | 440.3 (79.7) | 0.2765 | 0.1754 | |

| Language | ||||||

| Semantic Memory - #Animals in 60sec | 17.6 (5.7) | 17.9 (4.2) | 18.9 (5.4) | 0.7740 | 0.0792 | 0.025 |

| COWA Total – sum of C, L, F | 44.3 (14.6) | 41.5 (11.4) | 40.4 (12.2) | 0.5982 | 0.3777 | |

| Executive | ||||||

| Backward -# times Correct | 7.1 (2.0) | 7.0 (1.8) | 6.8 (2.1) | 0.8270 | 0.6018 | 0.007 |

| Colorword # colors as words read | 33.0 (8.5) | 31.2 (9.5) | 30.4 (8.7) | 0.5835 | 0.4137 | |

| Digit Data | 55.2 (9.9) | 58.8 (13.1) | 56.1 (12.5) | 0.1391 | 0.4548 | |

| Symbol Data | 24.8 (6.4) | 26.3 (6.7) | 24.7 (6.2) | 0.2776 | 0.7083 | |

| Trails B Errors | 0.51 (0.72) | 0.78 (1.2) | 0.62 (1.15) | 0.5837 | 0.7423 | |

| Trails Making Test Part B seconds | 76.8 (18.9) | 82.6 (29.3) | 93.9 (39.4) | 0.8543 | 0.2544 | |

| IED Ratio – Errors/Trials | 0.25 (0.10) | 0.26 (0.08) | 0.31 (0.10) | 0.4577 | 0.0520 | |

| IED Total Errors | 22.8 (12.3) | 26.7 (13.3) | 32.1 (16.0) | 0.3242 | 0.0597 | |

| SSP Span | 5.2 (0.6) | 5.2 (0.85) | 5.1 (0.83) | 0.8538 | 0.7612 | |

| SSP Total Errors | 14.5 (6.0) | 12.8 (4.5) | 13.8 (6.8) | 0.3034 | 0.6236 | |

| SWM Strategy | 27.5 (3.9) | 27.3 (4.0) | 26.6 (4.8) | 0.9189 | 0.4208 | |

| SWM Total Errors | 37.0 (20.3) | 38.1 (16.9) | 35.8 (16.5) | 0.7377 | 0.6151 | |

Models are adjusted for age, sex, years of education, Beck Depression Inventory-II, and APOE status (0 ε4 alleles vs. 1 or more).

Abbreviations: COWA=Controlled Oral Word Association; IED= Intra-Extra Dimensional set shift; MoCA=Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PAL=Paired Associates Learning; PRM=Pattern Recognition Memory; RTI=Reaction Time; RVP=Rapid Visual Information Processing; SD=Standard Deviation; SSP=Spatial Span; SRM= Spatial Recognition Memory; SWM=Spatial Working Memory; VRM=Verbal Recognition Memory

The effects of ‘523’ might be confounded by APOE ε status, therefore we re-analyzed the data using a restricted sample of individuals with the APOE ε3/3 genotype (n=82). In order to keep ‘523’ genotype groups defined clearly by the S and VL alleles, we dropped one participant who had ε3/3 genotype and carried the L allele. We retained 82 ε3/3 individuals with S/S (n=21), S/VL (n=39), and VL/VL (n=22) genotypes at the‘523’ locus. Table 3 lists the p-values for the GLM models for selected tests comparing the S/S group to the S/VL and the VL/VL groups. In the restricted analyses, the differences in memory between the S/S and the S/VL groups on the PAL (p=0.01 mean trails; p=0.02 mean errors) and VRM (p= 0.03 free recall items correct) tests became significant. The S/S group also performs significantly better on the RVP test (attention; p=0.04) and Digit Data (executive function; p=0.03). Differences between the S/S group and the VL/VL group are suggested on the Trail Making test part A and IED but not significant. After Bonferroni adjustment none of the associations remained significant (Table 3).

Table 3. Adjusted from APOE 3/3 subsample n=82.

| ‘523’ Genotype Group | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Domain Test |

S/S n=21 |

S/VL n=39 |

VL/VL n=22 |

S/S vs. S/VL |

S/S vs. VL/VL |

Corrected p-value threshold |

| Memory | ||||||

| PAL Mean Errors to Success | 5.7 (4.3) | 12.6 (13.1) | 8.7 (6.2) | 0.0204 | 0.2357 | 0.01 |

| PAL Mean Trials to Success | 3.1 (1.3) | 5.0 (3.5) | 4.1 (2.0) | 0.0163 | 0.1928 | |

| VRM Free Recall Items Correct | 8.3 (2.5) | 5.9 (3.4) | 6.5 (3.5) | 0.0325 | 0.2504 | |

| Attention | ||||||

| RVP Latency | 460.2 (69.8) | 420.3 (71.0) | 439.1 (80.7) | 0.0475 | 0.1460 | 0.008 |

| Executive | ||||||

| Digit Data | 53.9 (10.1) | 61.8 (13.8) | 53.7 (10.9) | 0.0349 | 0.6961 | 0.007 |

| IED Ratio Errors/Trials | 0.25 (0.1) | 0.26 (0.08) | 0.32 (0.09) | 0.8674 | 0.0771 | |

| IED Total Errors | 22.6 (11.5) | 12.6 (13.1) | 34.5 (16.8) | 0.9168 | 0.0905 | |

Models are adjusted for age, sex, years of education, and Beck Depression Inventory-II

Abbreviations: IED= Intra-Extra Dimensional set shift; PAL=Paired Associates Learning; RVP= Rapid Visual Information Processing; VRM=Verbal Recognition Memory

4. DISCUSSION

We tested the association between ‘523’ genotypes and neuropsychological function across a number of broad processing domains in a group of cognitively normal older adults and found significant differences in test performance. In comparisons with all ‘523’ genotypes, and adjusting for APOE ε4 status, we attempted to disentangle the effects of APOE and TOMM40. Findings in these analyses were not particularly strong due to the small sample size. However, a few items of interest suggested possible associations in the initial analysis, e.g., the number of errors on the paired associates learning (PAL) test, the number of items recalled in a test of free recall (VRM), and the ratio of errors to trials in the intra-extra dimensional set shifting task (IED).

Restricting the sample to individuals with APOE ε3/3 only and comparing S and VL homozygotes and heterozygotes, our results became more evident. Differences were found in memory, attention, and executive function. The PAL test on the CANTAB provides measures of episodic memory and learning and is particularly sensitive to early memory changes. We found that on average, the S/S group had 7 fewer errors than the S/VL group and 3 fewer errors than the VL/VL group on PAL. The S/VL group had the fewest items correct on VRM free recall number of items correct, about 2 fewer than the S/S group on average. The Trail Making Test Part A is a gauge of attention level. Although the difference was not significant, S/S group performed 7 seconds faster on average than the VL/VL group. On a second measure of attention, Rapid visual information processing (RVP latency) from the CANTAB, there were significant differences in latency time between the S/S group and the S/VL group. In executive function, the S/S group performed better on a digit-symbol substitution task than the S/VL group. Finally, the IED is a test of rule acquisition and shifting attention and is a measure of executive function. This was marginally significant in the initial analysis and less so in the restricted analysis although the VL/VL group had on average 11 more total errors on IED than S/S.

Collectively we showed that in cognitively normal participants, the S/S homozygotes had better cognitive performance than those with the AD-risk VL allele. Moreover, the L and VL ‘523’ genotypes in this group of normal elderly showed mild deficits in cognitive domains that are typically affected in early AD. These findings are in line with a previous study that found significant associations between memory and learning functions deficits that occur in LOAD, and the ‘523’ genotype in normal late middle-aged subjects[5]. Together these studies imply that the TOMM40 ‘523’ effect on cognition in normal subjects might be attributed to its association with AD risk. Further studies to elucidate the functional contribution of the ‘523’ polymorphism to the etiology of AD will be important.

Although research into the cognitive effects associated with the TOMM40 ‘523’ alleles is relatively recent, there have been numerous neuropsychological studies demonstrating early cognitive changes associated with later onset of AD. These studies suggest that in addition to the expected deficits in memory, the pre-clinical phase of cognitive decline preceding the emergence of AD involves other cognitive impairments[18] including attention and executive function[19-21] [22, 23]. Similarly, a recent study examined neuropsychological functioning using the CANTAB in adults with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and reported deficits in working memory attention and executive measures [24]. Interestingly, our study found that these particular cognitive domains are associated with the AD-risk ‘523’ genotypes.

Our study’s strength lies in the extensive neuropsychological battery that was administered which included conventional and computerized measures allowing for greater sensitivity in detecting subtle cognitive variations. The battery comprehensively covered cognitive domains of memory, attention, language, and executive function, all commonly affected early in AD. To date there are few studies that explore the effects of the ‘523’ genotype on cognitive function. The current study is one of the first to focus on the S allele, suggesting it offers some protection, akin to early studies of the APOE ε2 allele. Our results demonstrate subtle but detectable differences between groups of individuals categorized by their ‘523’ genotypes exclusive of APOE genotype that warrant follow up investigation in a larger group.

There are few limitations to the study that should be noted. First and foremost is the small sample size which limited our power to detect associations. Multiple comparisons were made in this study. Although we downplayed corrections for these comparisons due to the exploratory nature of the work, we reported corrected p-values and by that standard, none of our results were significant. The study sample is relatively homogenous (elderly, white, highly educated, and mostly female), thus the findings cannot be generalized to the broader population. One benefit of a homogenous sample, however, is the potential for controlling bias due to unmeasured variables. Another limitation is the lack of clinical assessments to determine the cognitive status of study participants. Nonetheless, the presence of symptomatic AD or other dementias is not likely as all individuals were living independently in the community at the time of the interview. In addition, individuals with self-reported clinical diagnosis of neurological diseases, history of stroke or TIA, dementia diagnoses, or the use of memory medications (e.g. Aricept) were excluded from the study. Finally, because of the age range of the participants (64-93) we were unable to investigate the early deleterious effects of the VL allele, thought to occur prior to age 65.

In the current study we showed that the ‘523’ genotypes may affect cognitive performance in elderly. The study is cross sectional, showing a snapshot of cognitive performance in relation to ‘523’ genotypes. It will be of great interest to evaluate the effect of the ‘523’ polymorphism on rate of cognitive decline in aging. Therefore, a follow up longitudinal study to assess the ‘523’ influence on cognitive changes and decline in our study’s participants is underway. Interestingly, a recent genome wide association study identified a significant association between the TOMM40 gene and survival into old age [25]. It will be important to assess the association of the ‘523’ polymorphism in that cohort as well as in other large nonagenarian cohorts in order to get a better understanding of the genetic factors that contribute to longevity and successful cognitive aging.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded in part by the Ellison Medical Foundation New Scholar award AG-NS-0441-08 (to OC) and the NIA grant K01 AG029336 (to KH).

The authors would like to thank Drs. Jeffrey Browndyke and Heather Romero for their neuropsychological expertise in interpreting CANTAB results, and Dr. Elizabeth Cirulli and Mrs. Kristen Linney for their helpful advice on recruitment procedures.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE

Dr. Roses is the CEO of Cabernet Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a pipeline pharmacogenetics consultation and project management company; and CEO of Zinfandel Pharmaceuticals, Inc., who is in alliance with Takeda Pharmaceuticals to perform a delay of onset trial for dementias of the Alzheimer type. Drs. Saunders and Lutz are Members of the Joint Biomarker Committee for the Zinfandel-Takeda Alliance clinical trial and Dr. Saunders is the spouse of Dr. Roses.

References

- 1.Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel D, St. George-Hyslop PH, Pericak-Vance MA, Joo SH, et al. Association of apolipoprotein E allele e4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1993;43(8):1467–72. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.8.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roses AD, Lutz MW, Amrine-Madsen H, Saunders AM, Crenshaw DG, Sundseth SS, et al. A TOMM40 variable-length polymorphism predicts the age of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacogenomics J. 2010;10(5):375–84. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2009.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lutz MW, Crenshaw DG, Saunders AM, Roses AD. Genetic variation at a single locus and age of onset for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(2):125–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.01.011. PMCID: 2874876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caselli RJ, Saunders A, Lutz M, Heuntelman M, Reiman E, Roses A. TOMM40, APOE, and age of onset of Alzheimer’s disease Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2010;6(4):S202. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson SC, La Rue A, Hermann BP, Xu G, Koscik RL, Jonaitis EM, et al. The effect of TOMM40 poly-T length on gray matter volume and cognition in middle-aged persons with APOEε3/ε3 genotype. Alzheimers Dement. 7(4):456–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.11.012. PMCID: 3143375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green P. Story Recall Test. Green’s Publishing; Edmonton, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scales. 3rd ed The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Army U. Army Individual Test Battery. Manual of Directions and Scoring. War Department, Adjutant General’s Office; Washington, DC: 1944. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reitan R. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8:271–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benton A, Hamsher K, Sivan A. Multilingual Aphasia Examination: Manual of Instructions. AJA Associates Inc.; Iowa City, IA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golden C. The measurement of creativity by the Stroop Color and Word Test. Journal of personality assessment. 1975;39:502–6. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa3905_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linnertz C, Saucier L, Ge D, Cronin KD, Burke JR, Browndyke JN, et al. Genetic regulation of alpha-synuclein mRNA expression in various human brain tissues. PLoS One. 2009;4(10):e7480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007480. PMCID: 2759540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koch W, Ehrenhaft A, Griesser K, Pfeufer A, Muller J, Schomig A, et al. TaqMan systems for genotyping of disease-related polymorphisms present in the gene encoding apolipoprotein E. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2002;40(11):1123–31. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2002.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luis CA, Keegan AP, Mullan M. Cross validation of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in community dwelling older adults residing in the Southeastern US. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(2):197–201. doi: 10.1002/gps.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 3ed Harper Collins; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association workgroup. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Backman L, Jones S, Berger AK, Laukka EJ, Small BJ. Multiple cognitive deficits during the transition to Alzheimer’s disease. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grober E, Hall CB, Lipton RB, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM, Kawas C. Memory impairment, executive dysfunction, and intellectual decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008;14(2):266–78. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708080302. PMCID: 2763488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayden KM, Warren LH, Pieper CF, Ostbye T, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, et al. Identification of VaD and AD prodromes: the Cache County Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2005;1(1):19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kramer JH, Nelson A, Johnson JK, Yaffe K, Glenn S, Rosen HJ, et al. Multiple cognitive deficits in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(4):306–11. doi: 10.1159/000095303. PMCID: 2631274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ribeiro F, de Mendonca A, Guerreiro M. Mild cognitive impairment: deficits in cognitive domains other than memory. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;21(5-6):284–90. doi: 10.1159/000091435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saunders NL, Summers MJ. Attention and working memory deficits in mild cognitive impairment. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2010;32(4):350–7. doi: 10.1080/13803390903042379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deelen J, Beekman M, Uh HW, Helmer Q, Kuningas M, Christiansen L, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a single major locus contributing to survival into old age; the APOE locus revisited. Aging Cell. 2011 Mar 21; doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00705.x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]