Abstract

Superstitious behaviors have been studied extensively in adults and non-human species, but have not been systematically assessed in children. The purpose of the study is to develop and validate a method of measuring superstitious tendencies in young children based on an established learning paradigm. In two studies, 3- to 5-year-olds tapped a computer to make a target image appear. On half the trials, a sensory stimulus appeared at a random time before the target. Superstitious tendencies were measured by change in tapping during the presence of the sensory stimulus. Children’s proportion of tapping increased during the presence of the sensory stimulus, indicating that children associated the sensory stimulus with the appearance of the target image, even though the two stimuli were not causally related. Implications for the development of superstitious tendencies and children’s causal knowledge are discussed.

Keywords: children’s causal understanding, sensory superstition, superstitious tendencies

1. Introduction

One influential way we learn about the world is by drawing causal conclusions based on our experiences and observations of the environment (e.g., Schulz & Gopnik, 2004). When people witness events that occur at the same time or in the same space, like flipping a switch and the lights turning on or a friend becoming angry after being yelled at, they tend to interpret these events as causally related. Indeed, even young infants draw conclusions about causal relationships (Sobel & Kirkham, 2006). Recent research shows that, if given the appropriate experience, infants as young as 4.5 months old can perceive physical causality (Rakison & Krogh, 2012). As this ability develops, it allows us to acquire important knowledge about the physical laws and psychological principles governing our world.

However, this tendency can easily lead us astray, resulting in causal inferences even in situations where two events are merely coincidental. Not only can forming such incorrect causal conclusions lead to inaccurate beliefs, they can result in superstitious behaviors, behaviors that are based on illusory contingencies in the environment (Skinner, 1948). For example, people who blow on a pair of dice before rolling may perceive a contingency between their blowing behavior and rolling the desired numbers. After multiple instances in which blowing on the dice is followed by the desired outcome, the player may form an inaccurate conclusion about his or her behavior. In other words, he or she has formed a superstitious behavior, perceiving a contingency between the behavior and a “lucky” outcome that does not actually exist.

Personal superstitions such as these represent a large group of beliefs and actions that are not culturally bound, but instead held only by a single individual. Skinner (1948) first presented an operant explanation for personal superstitions. Skinner placed food-deprived pigeons in operant-conditioning chambers in which food was presented every 15 s. Although the food delivery was independent of the pigeons’ behaviors, six of the eight pigeons displayed clearly defined behaviors as a result of this schedule. One pigeon was conditioned to turn counterclockwise about the operant-conditioning chamber while others demonstrated behaviors such as making head thrusts or hopping about the cage. Operant conditioning requires that a contingency be in effect for learning to take place. For Skinner’s pigeons, this traditional contingency did not exist; the presentation of food was not contingent on the behavior of the pigeon’s in any way. Rather, for superstitious behaviors, accidental juxtapositions of reward and a response establish an apparent contingency. From our previous example, it is likely that the person rolling the dice did not originally believe blowing on the dice would produce the desired numbers. However, when the random behavior is followed by the desired result, it creates an illusory contingency. The person therefore increases the frequency of that behavior, making it even more likely to coincide with the reinforcer. Consequently, this positive feedback loop strengthens the conditioning of these individual responses resulting in behaviors Skinner named “superstitions” (p.171).

Skinner and Morse (1957) demonstrated that stimulus control of a behavior can also be superstitiously reinforced. A stimulus present at the time of reinforcement, such as a light or a tone, may acquire discriminative control over the response even though its presence during reinforcement is spurious. Skinner and Morse demonstrated this experimentally by placing pigeons on a variable interval schedule, during which the pigeons’ pecking was reinforced randomly once every 30 min. During the trial, a blue light was projected for 4 min per hour. All the pigeons changed their rate of responding during the period of blue light. Some increased their rate of pecking, while others greatly decreased responding despite the fact that the light stimulus had no bearing on the contingency in effect. They termed this illusory stimulus control, “sensory superstition” because the sensory stimulus (i.e., the light) elicited superstitious behaviors in the pigeons (p. 308).

Many researchers have implemented different methodologies based on Skinner’s (1948) original experiment (Bloom, et al., 2007; Catania & Cutts, 1963; Weisberg & Kennedy, 1969; Hollis, 1973; Aeschleman et al., 2003; Rudski, 2000). Ono (1987) replicated Skinner’s original study with humans and was able to elicit similar behaviors in undergraduate students. Ono seated students in a small booth with three levers in front of them, a light, and a counter similar to an odometer. The students were instructed to try to get as many points on the counter as possible but were not told how to do so. At the end of each trial, presented on either a fixed or variable reinforcement schedule, the buzzer sounded, the light flashed, and a point was added to the counter. Ono found that 3 of the 20 participants developed persistent superstitious behaviors, pulling the levers in specific orders and for specific durations before the reinforcement. Although the counter, light, and buzzer activated independently of the students’ responding, three students accidentally associated their behavior with gaining points on the counter. This study illustrates that humans are susceptible to superstitious behaviors, although the effect was not as robust as Skinner’s original study with pigeons.

Ono (1987) also investigated Skinner’s second type of superstition, sensory superstition. Participants sat in the same booth and received the same instructions, however they were exposed to three colored lights, which were presented independently of point deliveries and participants’ responses. Six subjects displayed marked sensory superstitions, altering their response patterns and rates as a function of change in the lights. As demonstrated in Ono’s experiments, humans’ superstitious behaviors including sensory superstition can emerge relatively quickly during experimental prompting.

Although superstitious behaviors are well understood in animals and adults, there is a dearth of research on how superstitious behaviors develop beginning in childhood. One notable exception is Wagner and Morris (1987), in which 3- to 6-year-old children were asked to collect marbles from a toy clown’s mouth, which dispensed marbles on a fixed-time schedule of 15 or 30 s. Even though the marbles appeared regardless of the children’s behavior, more than half of the children displayed idiosyncratic behaviors that increased near to when the marbles were dispensed. These behaviors included thumb-sucking and kissing or touching the clown’s nose, suggesting that these children formed a causal relationship between their own behaviors and the dispersal of the marbles. While this study suggests that children may be prone to superstitious behaviors, the study’s sample size was too small and its method of detecting superstitious behaviors too imprecise to be able to draw any firm conclusions about these behaviors in preschoolers.

To date, there is no established method of precisely quantifying superstitious behaviors in children. The absence of such a method not only results in a dearth of information about children’s superstitious behaviors, but highlights the lack of knowledge about the trajectory of superstitious behaviors in general. A variety of open questions still exist concerning the prevalence and development of superstitious behaviors and how they might relate to other psychological constructs, like the formation of superstitious beliefs and causal knowledge. Having a method that easily and exactly quantifies children’s superstitious behaviors will allow researchers interested in both human learning and development to tackle these interesting and important questions.

2. Study 1

The purpose of the current study is to develop and validate a method of measuring children’s sensory superstitious behaviors based on extant learning paradigms that improve upon the method used by Wagner and Morris (1987). In the current study, children’s superstitious behaviors are referred to as “tendencies,” as we measured children’s change in behavior rather than any overt action. In the paradigm developed for this study, all stimuli were presented and participants’ responses were recorded with a computer using standard reaction time software, allowing for precise and accurate measurements.

2.1 Method

2.1.1.Participants

Twenty-four normally developing, English-speaking 3- to 5-year old children (M = 54.9 months, SD = 9.3 months, 63% female) were recruited from a database of interested families maintained by the second author, a local children’s museum, and area preschools. Informed parental consent was obtained for all participants. Children received a toy and stickers for their participation.

2.1.2. Materials

A sensory superstition paradigm based on to Skinner and Morse (1957) was created using SuperLab stimulus presentation software, a laptop computer, and a Mimo touch screen monitor measuring 23 × 14.5 × 2.5 centimeters. Children were given stickers as reinforcers during the superstition paradigm.

2.1.3. Procedure

Children were instructed to tap the touch screen monitor to make an image of a smiley face appear. Children first completed a practice session during which three taps were each reinforced by the appearance of the smiley face. After this continuous reinforcement, an experimenter explained to the child that sometimes they had to tap the screen many times to make the smiley face appear. Children then completed four practice trials with fixed ratios of 5, where they had to tap the screen 5 times before the smiley face appeared.

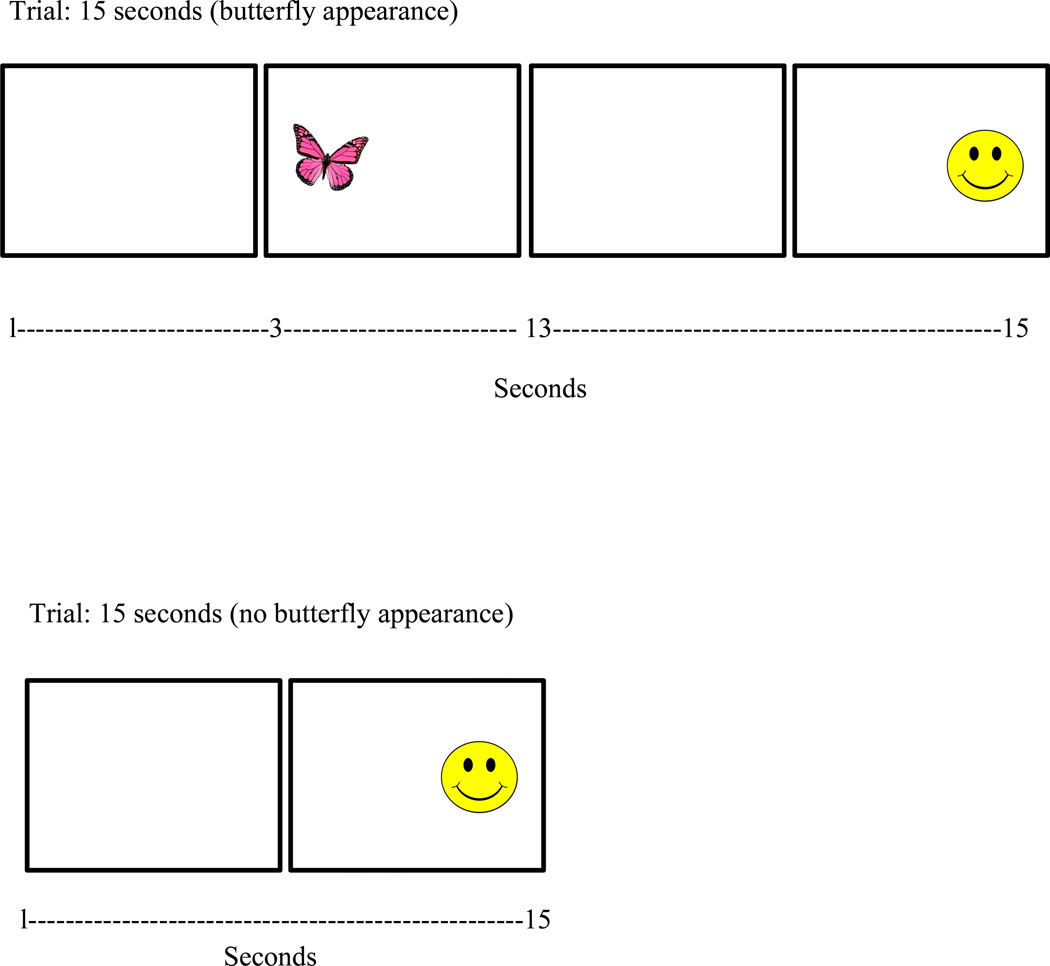

Children then completed 16 test trials, each trial ending with the child’s tap being reinforced by the appearance of the smiley face on the right side of the screen for 1 s. This reinforcer appeared after a response was made on a variable interval of 15 s, with trials ranging from 1 to 30 s (See Figure). Each time the smiley face appeared, the child received a sticker and verbal praise from the experimenter. On 8 of the trials, a butterfly appeared on the left side of the screen preceding the appearance of the smiley face at a random time during the interval, remaining for 10 s. The butterfly stimulus and the smiley face stimulus never appeared on the screen simultaneously. Importantly, the butterfly and smiley face were not related in any way; while children’s tapping was reinforced with the appearance of the smiley face, children’s tapping were not related to the appearance of the butterfly. If the child looked away from the screen for more than 3 s, the child was reminded of the instructions (e.g., “remember, we want to make the smiley face appear!”). All children experienced this reminder at some point during the procedure.

Figure.

Example presentation of stimuli on computer screen. Each trial ended with a smiley face appearing on the right side of the screen for 1 second. On half the trials, the butterfly appeared on the left side of the screen for 10 seconds randomly during that trial.

2.2 Results and Discussion

If children associated the appearance of the butterfly with the appearance of the smiley face, they should tap more while the butterfly was on the screen. Because trial lengths were variable, we investigated rate of tapping across trials by calculating the proportion of taps per second when the butterfly was on the screen compared to when no butterfly was on the screen. To test this, two proportion scores were calculated for each child. The first proportion divided the total number of taps when the butterfly stimulus was visible by the total seconds the butterfly stimulus appeared on the screen. The second proportion divided the total number of taps when nothing was on the screen by the total seconds of nothing on the screen.

Preliminary analyses indicated that there was no effect of gender on children’s responses, so gender was excluded from subsequent analyses. A paired-samples t test revealed that children’s proportion of taps during the butterfly (M = 1.12, SD = 0.58) was significantly greater than their proportion of taps during no butterfly stimulus (M = 0.84, SD = .38), t(23) = 4.64, p < .005, Cohen’s d = 0.95 . This suggests that children used the butterfly’s appearance as a discriminative stimulus for the smiley face reinforcer, even though the two events were unrelated. Further, this effect was pronounced, with 88% of children displaying a greater proportion of taps during the butterfly stimulus compared to when no butterfly stimulus was on the screen.

Age was significantly positively related to number of taps during the butterfly stimulus (r = .62, p = .001) and taps during no butterfly stimulus (r = .59, p = .003). However, no significant correlation was found between age and proportion of butterfly to no butterfly taps (r = .32, p = .13). These results indicate that older children were more likely to tap frequently during the session, but all children were equally likely to make an association between the butterfly and the smiley face stimuli.

These data indicate that the vast majority of participants exhibited superstitious tendencies. That is, their tapping indicates that they did associate the butterfly with the smiley face. Secondly, this study shows that these tendencies can be elicited and measured in young children using an established learning paradigm.

3. Study 2

The purpose of Study 2 is to replicate the procedure and the findings of Study 1 to ensure the method’s validity, as well as to test the design on multiple stimulus presentation software.

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

Participants were eighteen 3- to 5-year old children (M = 52.4 months, SD = 7.9 months, 39% female). Children were recruited and compensated in the same manner as Study 1.

3.1.2. Materials

In order to ensure this paradigm can be implemented on a variety of platforms, the superstition paradigm was re-created using E-Prime stimulus presentation program. Children were again tested using a laptop computer, but incompatibility with the stimulus presentation software prevented use of the touch-screen monitor. Children were again given stickers as reinforcers.

3.1.3. Procedure

The study was conducted almost identically to Study 1, except the test session consisted of 14 trials with 7 random presentations of the butterfly. Instead of tapping a touch screen, children pressed the mouse button on a laptop. Additionally, E-Prime allowed for the smiley face and the butterfly to appear according to two separate presentation schedules. Because these schedules ran simultaneously, the butterfly and smiley face could appear at the same time.

3.2. Results and Discussion

Children’s proportion scores were calculated as in Study 1. A significant difference was again found between proportions of presses during the butterfly (M = 1.72, SD = 1.22) and proportion of presses during no butterfly stimulus (M = 1.06, SD = 0.46), t(17) = 3.40, p = .003, Cohen’s d = 0.80. Eighty-nine percent of children displayed this pattern. And, again, no significant relationship between age and proportion of presses (r = .21, p = .40) was found, indicating that children of all ages were equally likely to make an association between the butterfly and the smiley face.

The replication of Study 1’s findings provides additional evidence that children are indeed susceptible to superstitious tendencies. More importantly, the replication of Study 1 validates this method as a precise way to quantify superstitious tendencies in preschoolers.

4. General Discussion

The results from both studies suggest that preschoolers made an association between two unconnected stimuli, which modified their behavior. The butterfly, acting as a sensory stimulus, served as a false signal to children that their tapping would soon be reinforced by the appearance of the smiley face. The children connected information from their environment, forming a means, albeit illusory, by which they could make the smiley face appear.

The primary purpose of this research, to develop a method that would quantify superstitious tendencies in young children, was accomplished by adapting a classic learning paradigm that has been used successfully with animals (Skinner & Morse, 1957) and adults (Ono, 1987) for use with preschool-age children. The procedure developed and used in this study proved to be highly effective. First, it was easy to implement and worked well with two different reaction time software packages and two different computer-based responses (touch screen taps and mouse button presses). Second, this method allowed for much more precise measurement than previous studies (e.g., Ono, 1987; Wagner & Morris, 1987), which relied on experimenters’ observations of participants’ behaviors, such as looking for distinctive patterns, idiosyncratic actions, or repetitive behaviors.

This study provides evidence for an early human susceptibility to superstitious behaviors, but also begs for more research on the developmental trajectory of such tendencies. Superstitious behaviors, as observed in adults, can be reliably elicited in at least some participants with response-independent reinforcers. However, little research has quantified the normal development of superstitious behaviors from its earliest manifestation – children. Previous research hinted that the acquisition of superstitious behaviors is more common in children than adults (Ono, 1987; Wagner & Morris, 1987). The present research confirms that superstitious tendencies can be elicited in preschoolers using a sensory paradigm. However, testing adults with this computer paradigm would confirm whether high susceptibly to sensory superstition is unique to children. In addition to more research on the development of superstitious tendencies from the preschool period through adulthood, research with infants and toddlers is needed to provide a complete developmental timeline and elucidate whether large individual differences in the acquisition of superstitions is due to age or method of measurement. There is little reason to believe that superstitious tendencies would be absent even in the youngest infants, given that other types of learning, like habituation and classical conditioning, can be observed well before birth (James, 2010). Empirical evidence is needed to confirm this hypothesis, which would reveal whether the propensity to form illusory correlations is a privileged type of learning in humans.

These results might seem to stand in stark contrast to the many studies showing preschoolers’ accurate understanding of causal relationships (e.g., Gopnik & Sobel, 2000). Explicit causal understanding is well-established by the preschool period, a fact which has been illustrated over the last decade by the “blicket detector” line of studies (e.g., Gopnik & Sobel, 2000). Young children are introduced to a novel machine and shown that only some objects (“blickets”) make the machine activate. Children then must infer what other object(s) make the machine “go”. This paradigm has revealed that young preschoolers are able to select causally relevant objects rather than objects that were merely associated with the activation of the blicket detector. By 4 years old, children show advanced causal understanding of variation and co-variation (Gopnik, Sobel, Schulz, & Glymour, 2001), estimation and probability (Sobel, Tenenbaum, & Gopnik, 2004; Gopnik et al., 2004), and the causal potential of internal properties (Sobel, Yoachim, Gopnik, Meltzoff, & Blumenthal, 2007). However, even though preschoolers have the ability to explicitly draw appropriate causal conclusions, it has long been noted that they also make erroneous causal associations (Piaget, 1929/1951) and are especially susceptible to magical thinking. For instance, they believe their thoughts can cause objects to appear in the real world (Woolley, Browne, & Boerger, 2006) and endorse fantastical processes as well as fantasy figures that can break real-world laws (Woolley, Boerger, & Markman, 2004).

The degree to which children’s associative behavior, like that measured in this study, and their explicit causal reasoning are related is an important and heretofore unstudied one. For instance, can a superstitious behavior lead to a superstitious belief? And, do children with more pronounced superstitious tendencies have more inaccurate causal knowledge? In the present study, even though children’s behaviors reveal they made an implicit association between the images, we doubt they formed a belief the two were causally related. Although explicit belief was not formally assessed in this study, it is worth noting that no child gave any spontaneous utterance during the task indicating they had formed a casual belief relating the butterfly and the smiley face. This leads us to hypothesize that preschoolers’ explicit causal knowledge can be quite separate from their implicit associative behavior. This implicit/explicit split is well-documented in a number of domains, including preschoolers’ magical thinking (Harris, Brown, Marriott, Whittall, & Harmer, 1991; Woolley, 2006). Another reason to believe that children’s implicit associative behavior operates differently than their explicit causal reasoning is that our results indicate that children’s associative behaviors are not sensitive to probability information, as their causal understanding is (Gopnik et al., 2004). Children in the current study saw the butterfly appear before the smiley face only on half of the trials. If children were utilizing probability information, they would be equally as likely to associate the butterfly with the smiley face as they would to make no association at all, which did not occur. Future research should explore whether and under what circumstances an implicit association, like a superstitious tendency, could lead to an incorrect or superstitious belief.

Superstitious behaviors seem to be a genuine attempt for living things to make meaningful relationships using information in the environment. Finding relationships and then pruning out the non-contingent ones is a necessary process in order for humans to develop a complete and accurate understanding of the world. The results from the current research are the first to show that a learning paradigm measure created for use with animals can be used to quantify superstitious tendencies in young children. Animal and adult studies on superstitious behaviors have advanced the understanding of how responses can be shaped by reinforcers in the environment although there seems to be no obvious contingencies. Moreover, these studies begin to shed light on how such adventitious reinforcement contributes to the development of abnormal superstitions and behaviors such as phobias (Mellon, 2009). Thus, these measurements have great potential for future research: for instance, they could contribute to our understanding of how children’s illusory causal behavior is related to their causal knowledge, or how superstitious tendencies transform into true superstitious behavior.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-

-

Preschool-age children performed a sensory superstition task on a computer

-

-

Measured superstitious tendencies by change in behavior during the sensory stimulus

-

-

In two studies, tapping behavior on computer increased during sensory stimulus

-

-

Elicited superstitious tendencies in 88 percent and 89 percent of participants

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere thanks to the preschools, children, and families who participated; the Providence Children’s Museum; and to Katherine Boguszewski for her help in data collection. This work was supported by two Undergraduate Research Grants awarded to the first author, one from Providence College and one from Psi Chi The International Honor Society in Psychology. The project described was supported in part by grants from the National Center for Research Resources (5P20RR016457-11) and the National Institute for General Medical Science (8 P20 GM103430-11). Components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIGMS or the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aeschleman SR, Rosen MR, Williams MR. The effect of non-contingent negative reinforcement operations on the acquisition of superstitious behaviors. Behavioural Processes. 2003;61:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(02)00158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom CM, Venard J, Harden M, Seetharaman S. Non-contingent positive and negative reinforcement schedules of superstitious behaviors. Behavioural Processes. 2007;75(1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania A, Cutts D. Experimental control of superstitious responding in humans. Journal of The Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1963;6(2):203–208. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1963.6-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E-Prime (Version 2.0) [Computer Software] Sharpsburg, PA: Psychology Software Tools, Inc.; [Google Scholar]

- Gopnik A, Sobel DM. Detecting blickets: How young children use information about novel causal powers in categorization and induction. Child Development. 2000;71(5):1205–1222. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopnik A, Sobel DM, Schulz L, Glymour C. Causal learning mechanisms in very young children: Two, three, and four-year olds infer causal relations from patterns of variation and co-variation. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:620–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopnik A, Glymour C, Sobel DM, Schulz LE, Kushmir T, Danks D. A theory of causal learning in children: Causal maps and Bayes nets. Psychological Review. 2004;111(1):3–32. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PL, Brown E, Marriott M, Whittall S, Harmer S. Monsters, ghosts and witches: Testing the limits of the fantasy – reality distinction in young children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1991;9:105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hollis JH. “Superstition”: The effects of independent and contingent events on free operant responses in retarded children. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1973;77(5):585–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James DK. Fetal learning: a critical review. Infant and Child Development. 2010;19:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mellon RC. Superstitious perception: Response-independent reinforcement and punishment as determinants of recurring eccentric interpretations. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:868–887. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K. Superstitious behavior in humans. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1987;47:261–271. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1987.47-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. In: The Child's Conception of the World. Tomlinson J, Tomlinson A, translators. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.; 1929/1951. (originally published by London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, Ltd). [Google Scholar]

- Rakison DH, Krogh L. Does causal action facilitate causal perception in infants younger than 6 months of age? Developmental Science. 2012;15(1):43–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudski JM. Effect of delay of reinforcement on superstitious inferences. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 2000;90:1047–1058. doi: 10.2466/pms.2000.90.3.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz LE, Gopnik A. Causal learning across domains. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40(2):162–176. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Superstition in the Pigeon. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1948/1992;38:168–172. doi: 10.1037/h0055873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF, Morse WH. A second type of “superstition” in the pigeon. The American Journal of Psychology. 1957;70:308–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel DM, Kirkham NZ. Blickets and babies: the development of causal reasoning in toddlers and infants. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1103–1115. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel DM, Tenenbaum JB, Gopnik A. Children's causal inferences from indirect evidence: Backwards blocking and Bayesian reasoning in preschoolers. Cognitive Science. 2004;28:303–333. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel DM, Yoachim CM, Gopnik A, Meltzoff AN, Blumenthal EJ. The blicket within: Preschoolers' inferences about insides and causes. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2007;8:159–182. doi: 10.1080/15248370701202356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SuperLab (Version 4.0) [Computer Software] San Pedro, CA: Cedrus Corporation; [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GA, Morris EK. “Superstitious” behavior in children. The Psychological Record. 1987;37:471–488. [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg P, Kennedy DB. Maintenance of children's behavior by accidental schedules of reinforcement. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1969;8(2):222–233. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley JD. Verbal-behavioral dissociations in development. Child Development. 2006;77(6):1539–1553. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley JD, Boerger EA, Markman A. A visit from the Candy Witch: Children's belief in a novel fantastical entity. Developmental Science. 2004;7:456–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley JD, Browne CA, Boerger EA. Constraints on children's judgments of magical causality. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2006;7(2):253–277. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.