Abstract

The importance of family relations in children’s adjustment has been established, but questions remain about the contexts that account for these associations. Examining children’s reactions to family stress holds promise for advancing our understanding of the relations between attachment and school-related outcomes. The present study examined children’s attachment, basal cortisol, and emotional reactions in 235 community families, to understand contributions to children’s attitudes to school and scholastic competence. Children’s attachment security and normative basal cortisol both contributed to positive school outcomes, while insecurity in the context of low or high cortisol and emotional distress related negatively. Findings highlight the importance of examining stress in family contexts to advance the understanding of children’s school functioning, with implications for school mental health interventions.

Keywords: family relations, attachment, stress, cortisol, emotion, child adjustment

Introduction

An area of research relevant to school mental health (SMH) is the role of family processes in contributing to maladaptive functioning in children and adolescents. Research examining family processes has indicated that young people may be negatively impacted by many aspects of poor family functioning, with stress and coping playing critical roles (Cummings et al, 2000). Children’s regulation of stress in families characterized by poor functioning is likely to contribute to forms of coping which are adaptive in the short term but maladaptive or problematic in the long term, and to the development of emotional/behavioral problems and disorders in other contexts. Examining the role of children’s stress responses in the context of family risk not only advances our understanding of the development of emotional/behavioral problems, but also provides information to inform practice implications for SMH programs. Family processes may affect how children function in school, and SMH may also provide young people with protective factors that improve their family adjustment.

An important aspect of family functioning that has often been examined as critical in broad domains of children’s functioning is the development of attachment security. As a fundamental, enduring emotional bond between children and their parents, attachment relationship quality has been implicated in the development of difficulties in socio-emotional and school adjustment (Cassidy & Shaver, 2008; Roeser et al, 1998). Whereas secure attachment relationships provide children with assurance in confidently negotiating novel and challenging tasks in the school context, insecure attachment relationships undermine children’s abilities to reduce threat and restore security in ways that allow them to master the physical and social worlds (Ainsworth et al, 1978). Consistent with this thesis, children with insecure attachments are at risk for developing more difficulties in academic, social (peer and teacher relationships, for example) and emotional domains of school adjustment than children with secure attachments with parents (see Bergin & Bergin, 2009 for a review). However, at the same time many children do, in fact, develop competently despite experiencing insecure attachments with parents.

While research has established a modest association between attachment and children’s socio-emotional and psychosocial development, research and theory both suggest that these relations are dependent on other factors, including the developmental stage of the child, individual differences in child functioning, and the specific domains of child functioning being considered (Cassidy & Shaver, 2008). Identifying the individual differences that contribute to relations between attachment and adjustment will further our understanding of why, how and for whom attachment is related to specific domains of functioning. Toward the goal of understanding children’s resilience in the context of attachment insecurity, recent research has examined the individual differences in underlying neurobiological associations that exist to understand relations between family functioning and child adjustment (Nachmias et al, 1996). While research has established the direct impact of attachment on regulating stress, particularly in infancy, less research has examined the moderating role of risk contexts. Children’s neurobiological functioning may be one potential source of variability in relations between attachment and children’s mental health and school adjustment (Granger & Kivlighan, 2003). Thus, examining stress hormones and emotional reactions to family stress may further advance our understanding of the association between attachment and children’s subsequent mental health and school adjustment.

As early as preschool, secure attachment is associated with school success and development of other positive outcomes which contribute to success, such as attention span and cognitive abilities (Main, 1983; Moss & St-Laurent, 2001). Secure children are more likely to develop more positive attitudes toward reading and better reading skills than insecure children (Bus & van IJzendoorn, 1988). Insecure attachment has been associated with poor verbal and math abilities, difficulties with reading comprehension, and poor overall academic achievement (Granot & Mayseless, 2001; Jacobsen & Hofmann, 1997; Weinfeld et al, 1999). Moreover, Sroufe and colleagues (1983) found that insecure attachment in infancy was associated with poor socio-emotional functioning, including less curiosity, more dependency, and less social competence, as well as less emotional positivity than secure children. School relations for insecure children were characterized by difficulties in teacher and peer interactions, which have important implications for children’s difficulties with school adjustment. For example, antisocial and rejected children are more likely to have low achievement, reading and learning difficulties, attention and thought problems (Ladd & Burgess, 2001; Dishion et al, 1991). Additionally, children with emotional difficulties often fare worse in school because anxiety may interfere with learning (Gunnar et al, 1996).

Insecure children are also less likely to approach adverse circumstances (Sroufe et al, 1983). Learning and novelty elicit emotional arousal, which insecure children may seek to avoid as it is associated with poor coping skills. Insecure children are less able to discuss emotion-provoking topics, and respond more negatively to novel situations at school (Kobak et al, 1993). Insecure children may have difficulty in attending to school tasks because they are preoccupied with their own anxiety or emotional arousal, as previous research has shown a correlation between stress and poor school adjustment (Murray-Harvey & Slee, 1998). However, little is known about the role of stress and emotional arousal, which also probably contribute to relations between attachment and school-related outcomes.

Examining relations between attachment, adrenocortical functioning, and emotional arousal may further elucidate our understanding of when attachment is associated with school outcomes, and for whom. Decades of research have highlighted that stress hormones not only influence behavior and development, but also are affected by behavior, especially in examining the role of early caregiving experiences on stress (Loman & Gunnar, 2010; Nelson, 2000). Physiological systems, such as the limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (LHPA) axis, respond to and regulate stress in an effort to maintain homeostasis (Boyce & Ellis, 2005). This system is also affected by stress; basal levels of cortisol have been found to adapt to the environmental context over time.

Specifically, the hypocortisolism hypothesis suggests that, in the context of repeated exposure to chronic stressors, the stress response may become blunted or diminished over time, with reduced or low levels of cortisol in response to subsequent instances of stress. However, as cortisol levels increase, priming the individual to respond to threat, research also indicates that when an individual is confronted with mild stressors, stress may increase cortisol levels (for example the hypercortisolism hypothesis). Both excessive and diminished cortisol levels may indicate a failure of appropriate physiological coping, even though they are adaptive in regulating stress in the immediate context (Gunnar, 1994). Yet little research has examined the non-linear relations cortisol may have on behavior, even though both excessive and diminished levels are problematic (Booth et al, 1999). Findings are inconsistent regarding the role of high or low basal cortisol levels in adjustment, although both have been implicated as maladaptive. Further examination of these relations in specific social contexts may help to advance understanding of relations between cortisol responses and stress reactivity systems over time.

Specific to attachment and cortisol relations, insecure children evidence greater physiological reactivity than secure children in the context of different stressors (Spangler & Grossman, 1993; Sroufe & Waters, 1977). Research suggests that security acts as a buffer for LHPA reactivity in infants and young children (Gunnar et al, 1996; Spangler & Grossman, 1993), whereas insecure attachment is a chronic stressor for children (Tarullo & Gunnar, 2006). Insecure attachment is a maladaptive pattern of coping with stress in a poor caregiving environment and may represent a failure to cope with adversity (Spangler & Grossman, 1993). Moreover, in the context of emotionally distressing events, insecure children appear to be unable to use the caregiver to regulate stress, as indexed by cortisol levels, in response to these threats (Nachmias et al, 1996). However, less research has examined insecure children’s emotional responses to other stressful family contexts.

Research indicates the importance of multiple family systems in affecting child adjustment, especially that of negative interparental relations on child adjustment (Cummings et al, 2006), yet questions remain about the role of attachment security, adrenocortical functioning and emotional reaction to stress in multiple family contexts. Specifically, little is known about the potential role of children’s emotional reaction as a protective factor in the context of family stress for children who are insecure in the mother–child relationship. Little is known about the relationship between attachment and stress reactivity in affecting children’s school adjustment. Currently there are no studies that have examined interactions between children’s attachment, cortisol levels, emotional reactions to family stress during early childhood in relation to children’s attitudes toward school and scholastic competence. Examining the role of adrenocortical functioning in the specific context of family relations may help to further our understanding of the impact of attachment on school adjustment, and our understanding of the complex influences of family contexts on school behavior. Improving our knowledge of these relations is important for advancing understanding of the risks and protective processes in families which may inform research on family and children’s connectedness to school and help reduce barriers which prevent children from succeeding in school.

The current study examines physiological markers of stress, namely basal cortisol levels in children, and children’s emotional reaction to family stress, to examine their associations in the family context and the impact on children’s school-related outcomes. The aim of the research was to examine the role of emotional reaction to family stress as a protective mechanism in insecure children with maladaptive adrenocortical functioning, and to examine how these processes relate to children’s parent-reported scholastic competence and self-reported positive attitudes toward school. It was expected that children’s security would buffer against abnormally high or low cortisol levels – that is, foster adaptive cortisol responding – and relate to both greater parent-reported scholastic competence and more positive attitudes toward school. Additionally, risks such as insecurity and maladaptive cortisol levels were expected to relate to poor indicators of school outcomes.

Method

Participants

Participants were 236 community-recruited families from the Midwestern and Northeastern areas of the United States, including father, mother, and their kindergarten age child (130 girls; M age = 6.00; s.d. = .45), taking part in a multi-site longitudinal study examining the effects of family process on child adjustment (see Cummings et al, 2006, for a review). The children were racially and ethnically representative of the communities in which they lived in (71% European American, 14% African American, 13% Biracial, 2% Hispanic). Most couples were married (88.1%) and cohabitating for an average of 11 years (s.d. = 4.9). The median family annual income ranged between $40,000 and $54,999, although some families reported levels below $6,000 while others reported above $75,000. Most of the caregivers were biological mothers (94.5%) and fathers (87.7%) of the child; other caregivers included a small number of stepparents, adoptive parents, live-in girl-friends/boyfriends, or legal guardians.

Procedure

Families were recruited through flyers distributed in local communities; flyers were also sent home with students in schools and day-care agencies, and distributed at booths at community functions. Postcards were sent to local neighborhoods, and participants were also recruited through referrals from other participants. Eligibility requirements necessitated that families had lived together for at least three years, had a child enrolled in kindergarten, and could complete assessments in English. Families who met these criteria and were willing to participate were scheduled for two sessions approximately two weeks apart, each lasting about two and a half hours. Families completed questionnaires and participated in observational assessments. Families were paid a total of $65 for participation; children selected a toy of choice equivalent to $5. The study was conducted under the approval and direction of the University’s Institutional Review Board. At the beginning of each session, informed consent and assent was obtained from parents and children. Transportation and childcare were provided if necessary.

Mothers, fathers, and children attended the first visit, while only mothers and children returned for the second visit. Fathers were requested to participate in only one visit to increase the likelihood of father participation and retention over time. Each visit was approximately two and a half hours in length. Children’s basal cortisol levels were collected in conjunction with a simulated phone anger task that mother and child participated in during the first visit; the mother–child separation–reunion task (see below) was conducted during the second visit, and questionnaire assessments were collected during both visits.

Mother–child separation–reunion task

The Main and Cassidy (1988) Strange Situation procedure, adapted to be appropriate for kindergarten children, was used to assess mother–child attachment. Mother and child participated in a separation–reunion task, including a 55-minute long separation between the parent and child, and reactions were examined in a five-minute reunion. During the separation period, parents and children completed various other assessments and questionnaires in different rooms. Before the reunion, and consistent with the Strange Situation paradigm, the child was observed interacting with the experimenter and also playing alone. Upon reunion, the parent was instructed to respond to the child as they would normally at home in the context of play and they were observed for a five-minute period.

Children’s salivary cortisol collection

Children provided baseline cortisol levels collected after arrival in the laboratory setting, following a brief introduction to the laboratory and assent procedures. Basal cortisol levels were collected before the simulated phone anger task (see below) to assess a normative daily indication of physiological functioning. In accordance with typical sampling collection guidelines, children were asked to rinse their mouth to reduce the influence of contaminants present in the mouth. The sample was collected after seven minutes by the passive drool technique with the aid of a straw and Trident sugarless gums. Saliva collection occurred in the late afternoon and early evening to limit the effects of the natural diurnal pattern of cortisol production (average sampling time 3:43 pm; s.d. = 2 hours 15 minutes).

Simulated phone anger task

The simulated phone anger task consisted of children and mothers engaging in a play activity during which the mother received a phone call believed to be from the child’s father. Mothers were provided with a scripted interaction by a trained experimenter to stage a marital dispute over the phone. Before this task, mothers received training on how to convey the appropriate tone during this interaction; mothers were asked to display mild frustration and anger. Following this dispute, the mother received a second phone call from the father in which the mother staged a resolution of the issue of the original dispute, approximately ten minutes after the conclusion of the marital dispute. During this resolution, mothers were asked to display understanding and caring.

Measures

Children’s attachment security

The parent–child separation-reunion task was later coded for categorical assessments of attachment behavior (Cassidy & Marvin, 1992; Main & Cassidy, 1988). Extensive training for reliability and proficiency was established in concert with established experts at the University of Quebec at Montreal, using an adapted version of the Main and Cassidy coding system to ensure the coder’s ability to assess attachment in preschool and school-age children. Secure children exhibited comfort and pleasure throughout the reunion with mother, as indicated by the child’s initiation of positive interactions, proximity, and contact with the parent demonstrating the use of the parent to facilitate exploration and play. Insecure children displayed avoidant, ambivalent, or disorganized patterns of responses. Insecure children with avoidant strategies maintained or increased emotional and/or physical distance from the parent upon reunion. Insecure children with ambivalent or dependent attachments attempted to exaggerate intimacy, dependency, and helplessness with the parent. The child might show subtle anger or sadness toward the parent, and when seeking proximity show ambivalence (for example jerk away). Analyses included comparisons of secure versus insecure children, regardless of the type of insecure pattern. Eighty-per cent reliability was established with the expert coder. The distribution of children’s attachment with mothers in this sample comprised 144 (62%) who were secure (80 girls), 36 (16%) who were insecure-avoidant (21 girls), 31 (13%) who were classified as insecure-ambivalent/dependent (16 girls), 14 (6%) classified as insecure-controlling (6 girls) and 8 (3%) were insecure-other (3 girls). For the goals of the current study, insecure classifications were grouped and comparisons between the dichotomous attachment groups were conducted.

Children’s salivary basal cortisol level

Children’s samples were assayed for salivary cortisol using a highly sensitive immounassay at Salimetrics Inc. (State College, PA). The assay test process used 25 μl of saliva; samples were tested in duplicate form. The test had a lower test sensitivity of 0.007 μg/dl and an upper test sensitivity of 3.0 μg/dl; samples for the study ranged from 0.008 to 0.543μg/dl. The average intra-assay coefficient was 5.5% for the sample. Participants were excluded from the study if their cortisol levels were three or more standard deviations above or below the mean cortisol level of the sample (N = 2). Cortisol levels were distributed into three groups, because both low levels and high levels of cortisol have been associated with poorer adjustment; the low cortisol level group included scores greater than one standard deviation below the mean (N = 28), the high cortisol level group included scores greater than one standard deviation above the mean (N = 22), and the mid-level or normative group which incuded the majority of children centered on the mean (N = 111).

Children’s emotional reaction to family stress

Following the simulated anger task children were interviewed about the emotions experienced during their mother’s phone dispute. Children reported whether or not they had felt happy, scared, sad, or mad and the extent to which they felt each emotion (1 = very little to 5 = a whole lot). Children’s experience of negative emotion was assessed by their endorsement of at least one negative emotion (for example scared, sad, or mad). Seventy children indicated being emotionally distressed or experiencing some level of negative emotion, while the majority of children (N = 164) reported no experience of negative emotion. Similar techniques have been used to examine the intensity of children’s emotional reactions to interparental conflict (Cummings et al, 2007; Shamir et al, 2005).

Children’s parent-reported scholastic competence

Mothers and fathers completed the parent-reported scholastic competence subscale (five items) on the Parent-Report version of the Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC; Harter, 1982). Each item includes a forced choice between descriptions of child competence; a sample item includes ‘some children often forget what they have learned’ but ‘other children are able to remember all things easily’. Parents select the description that best describes their child and the extent to which the description fits (for example somewhat true or very true). Accordingly, each item is scored on a four-point scale, a higher scores reflecting more parent-reported scholastic competence. The SPPC scale has demonstrated reliability, as well as content and construct validity (Harter, 1982). Mothers and fathers scores were averaged across both parents to take advantage of the multi-informant data and reduce reporter bias.

Children’s positive attitude toward school

Children completed the nine-item School Liking and Avoidance Questionnaire (SLAQ; Ladd & Price, 1987). Children reported feelings of positivity toward school (for example ‘Are you happy when you are at school?’). Children responded to each item with 1 = no, 2 = sometimes, or 3 = yes. Children’s responses were summed, and higher scores indicated more positive attitudes toward school. The SLAQ has demonstrated reliability as well as content and construct validity (Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1996), specifically in the current sample as well (Sturge-Apple et al, 2008).

Results

Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to examine the main effects and interaction effects of children’s attachment, cortisol level, and emotional reaction on children’s parent-reported scholastic competence and positive attitudes toward school. All predictor variables were centered on the mean, consistent with procedures proposed by Aiken and West (1991), which also aids in the interpretation of the results.

For the entire sample, the mean of children’s parent-reported scholastic competence was 10.25 (s.d. = 1.03; N = 231) and the mean of children’s positive attitudes toward school was 23.78 (s.d. = 4.45; N = 234). The MANOVA model included the main effects for emotional reaction to family stress, attachment classification, and cortisol level, as well as the three two-way interactions and a three-way interaction; results of the overall MANOVA analyses are presented in Table 1, below. The results indicated significant main effects, and two-way interaction effects between cortisol level and emotional reaction, and between attachment and emotional reaction. The main and two-way interaction effects, however, were superseded by a significant three-way interaction among attachment, cortisol level, and emotional reaction to family stress in predicting children’s parent-reported scholastic competence and positive attitudes toward school.

TABLE 1.

Parent-Reported Scholastic Competence and Positive Attitudes toward School MANOVA Results

| Predictor variables | Wilks’ λ | F |

|---|---|---|

| Attachment | .97 | 2.95 (2,214)* |

| Cortisol | .98 | 1.08 (4,428) |

| Emotional distress | .96 | .79 (2,214)** |

| Attachment × cortisol | .97 | 1.85 (4,428) |

| Attachment × Emotional distress | .96 | .63 (2,214)** |

| Cortisol × Emotional distress | .94 | .27 (4,428)** |

| Attachment × Cortisol × Emotional distress | .93 | .88 (4,428)** |

p< .01;

p< .10

Children’s parent-reported scholastic competence

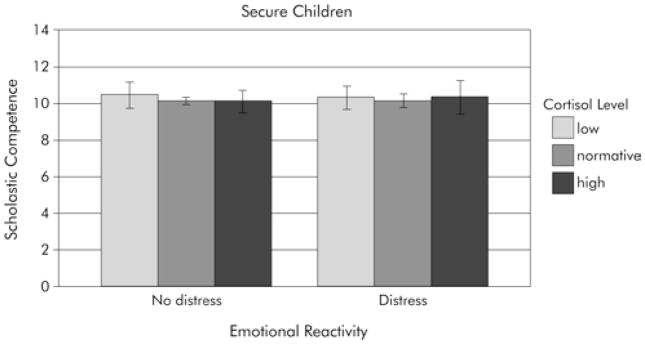

The results of between-subjects effects specifically predicting children’s parent-reported scholastic competence indicated a non-significant main effect of emotional reaction to family stress, and two two-way interactions of attachment and emotional reaction (F(1,215) = 4.06; p < .05) and cortisol level and emotional reaction (F(2,215) = 3.03; p < .05). However, there was a significant three-way interaction among predictor variables (F(2,215) = 4.10; p < .05) which superseded the main effect and two-way interactions, so they are not interpreted. Pairwise comparisons between groups were examined to further delineate simple main effects among groups in the three-way interaction for children’s parent-reported scholastic competence. Notably, comparisons indicated that there were no significant differences among secure children when considering cortisol level and emotional reaction to family stress, while differences existed among insecurely classified children (Figure 1, below).

FIGURE 1.

Parent-Reported Scholastic Competence for Secure Children among Differing Levels of Emotional Reactions and Basal Cortisol Levels

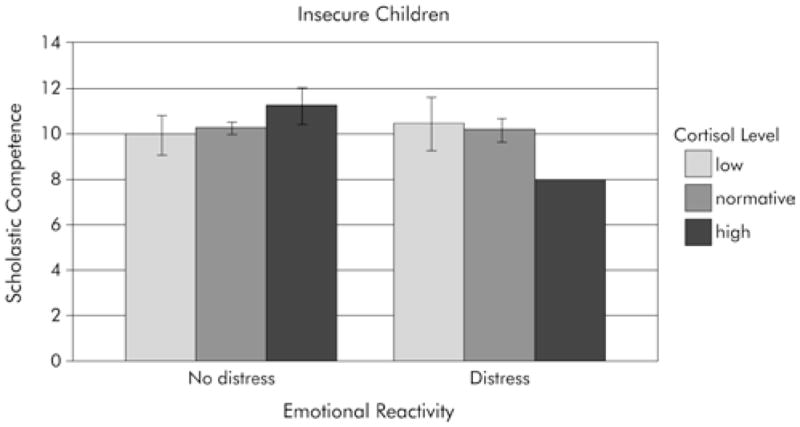

Differences between secure and insecure children

Post-hoc pairwise comparisons indicated significant differences among insecure children with higher cortisol levels who experienced emotional distress (Table 2, opposite). Overall, secure children did not differ on their level of parent-reported scholastic competence. Specifically, secure children had significantly higher levels of parent-reported scholastic competence than insecure children who had high cortisol levels and experienced emotional distress. To clarify, when children experienced emotional distress and had high levels of cortisol, secure attachment was associated with greater parent-reported scholastic competence, while insecure attachment was associated with the lowest levels of parent-reported scholastic competence. Comparisons also indicated a significant difference in attachment among non-emotionally distressed children who had high cortisol levels. Specifically, insecure children with high cortisol levels had greater parent-reported scholastic competence than secure children in this specific context not experiencing emotional distress. To clarify, when children were experiencing high cortisol levels but not reporting any emotional distress, security was not related to positive scholastic competence; rather interestingly in this specific context of mismatched reactivity, insecurity was associated with higher academic outcomes.

TABLE 2.

Children’s Parent-Reported Scholastic Competence

| Attachment | Emotional reaction | Low cortisol

|

Normative cortisol

|

High cortisol

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | s.d. | M | s.d. | M | s.d. | ||

| Insecure | No distress | 10.00a | 0.55 | 10.33b | 1.15 | 11.33abcd | 1.25 |

| Distress | 10.50e | 1.32 | 10.22f | 0.73 | 8.00defg | — | |

| Secure | No distress | 10.50 | 0.89 | 10.12 | 1.05 | 10.15c | 0.75 |

| Distress | 10.36 | 0.95 | 10.21 | 1.04 | 10.40g | 0.89 | |

Statistically significant pairwise comparison (p< .05): low differ from high cortisol levels within insecure, non-emotionally distressed children.

Statistically significant pairwise comparison (p< .05): normative differ from high cortisol levels within insecure, non-emotionally distressed children.

Statistically significant pairwise comparison (p< .05): insecure differ from secure within non-emotionally distressed children with high cortisol levels.

Statistically significant pairwise comparison (p< .01): emotionally distressed differ from non-emotionally distressed within insecure children with high cortisol levels.

Statistically significant pairwise comparison (p< .05): low differ from high cortisol levels within insecure, emotionally distressed children.

Statistically significant pairwise comparison (p< .05): normative differ from high cortisol levels within insecure, emotionally distressed children.

Statistically significant pairwise comparison (p< .05): insecure differ from secure within emotionally distressed children with high cortisol levels.

Differences among insecure children

Post-hoc pairwise comparisons also indicated significant differences among insecure children when considering cortisol levels and emotional reaction (Figure 2, below). Specifically, among emotionally distressed, insecure children, those with mid-range cortisol levels had greater parent-reported scholastic competence than those with high cortisol levels (Table 2). Thus, among insecure children who experienced emotional distress, having mid-range cortisol levels rather than high levels of cortisol was associated with greater parent-reported scholastic competence. In this context of insecurity and emotional distress, comparisons indicated a difference among emotionally distressed, insecure children, such that those with low cortisol levels also had greater parent-reported scholastic competence than those with high cortisol levels. Last, results indicated a significant difference among those insecure children who had high cortisol levels, such that non-emotionally distressed children had greater parent-reported scholastic competence than those who experience emotional distress. As follows, in the context of insecurity and high levels of cortisol, not experiencing emotional distress was associated with greater parent-reported scholastic competence than those experiencing distress.

FIGURE 2.

Parent-Reported Scholastic Competence for Insecure Children among Differing Levels of Emotional Reactions and Basal Cortisol Levels

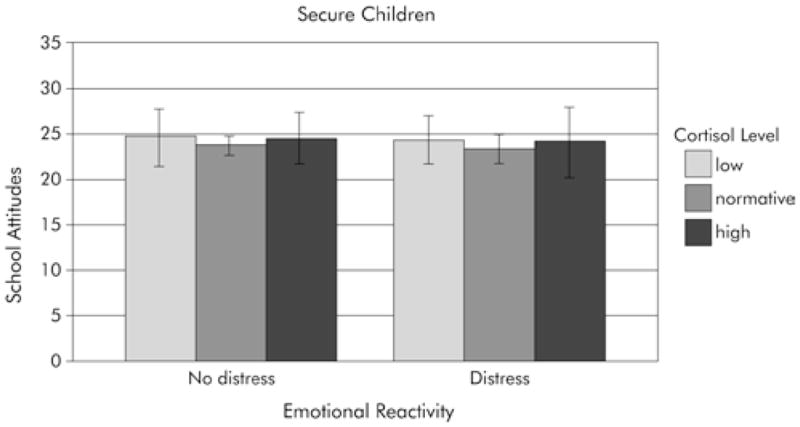

Children’s positive attitudes toward school

MANOVAs were also conducted to examine the specific relations with children’s positive attitudes toward school; models included the main effects of attachment security and emotional reaction, and cortisol level, as well as the two-way interactions of attachment and emotional reaction and cortisol levels and emotional reaction, and attachment and cortisol level, many of which were significant. However they are not discussed, because the significant three-way interaction (F(2,215) = 3.61; p<.05) supersedes the main and interactions effects.

Differences between secure and insecure children

To examine further the differences among the three-way interaction with children’s positive attitudes toward school, simple main effects between groups were investigated. The results suggested that there were no significant differences among secure children (Figure 3, below), regardless of the emotional distress or level of cortisol. Differences existed between secure and insecure attachment in the context of high cortisol levels and emotional distress, such that children who had high levels of cortisol and experienced emotional distress but were secure in their attachment had significantly more positive attitudes toward school than children in this context who were insecure in their attachment with mothers (Table 3, below).

FIGURE 3.

Positive Attitudes Toward School for Secure Children among Differing Levels of Emotional Reaction and Basal Cortisol Levels

TABLE 3.

Children’s Positive Attitudes Toward School

| Attachment | Emotional reaction | Low cortisol

|

Normative cortisol

|

High cortisol

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | s.d. | M | s.d. | M | s.d. | ||

| Insecure | No distress | 26.67a | 0.82 | 23.27 | 5.11 | 23.00b | 6.48 |

| Distress | 19.67a | 8.08 | 24.33c | 3.38 | 13.00bcd | — | |

| Secure | No distress | 24.63 | 3.07 | 23.79 | 4.50 | 24.60 | 2.84 |

| Distress | 24.45 | 3.11 | 23.42 | 4.57 | 24.20d | 2.28 | |

Statistically significant pairwise comparison (p< .05): emotionally distressed differ from non-emotionally distressed within insecure children with low cortisol levels.

Statistically significant pairwise comparison (p< .05): emotionally distressed differ from non-emotional distressed within insecure children with high cortisol levels.

Statistically significant pairwise comparison (p< .05):normative differ from high cortisol levels within insecure, emotionally distressed children.

Statistically significant pairwise comparison (p< .01): insecure differ from secure within emotionally distressed children with high cortisol levels.

Differences among insecure children

Pairwise comparisons also indicated differences among insecure children when accounting for cortisol level and emotional reaction (Figure 4, opposite). Among children who were emotionally distressed, insecure children with mid-range cortisol levels had more positive attitudes toward school than insecure children with high cortisol levels. Differences existed among insecure children with low cortisol levels, such that children who were not emotionally distressed had more positive attitudes to school than insecure children who were emotionally distressed. Similarly, differences in emotional reaction also existed among insecure children with high cortisol levels, such that children who were not emotionally distressed had more positive attitudes toward school than those insecure children with high cortisol levels who did experience negative emotional reaction to the family stress.

FIGURE 4.

Positive Attitudes Toward School for Insecure Children among Differing Levels of Emotional Reaction and Basal Cortisol Levels

Discussion

The results support the significance of examining the role of stress hormones and children’s emotional reactions in the family context to advance understanding of relations between children’s attachment and school outcomes. The findings regarding links between attachment and adjustment have been inconsistent, though modest associations exist; examining relations with children’s stress and reactivity may support more nuanced associations that contribute to children’s scholastic competency and attitudes toward school. Specifically, this study indicated relatively complex interactions among children’s attachment, basal cortisol levels, and emotional reaction to stress in understanding the effect on children’s school outcomes, notably for both children’s parent-reported scholastic competence and children’s positive attitudes toward school. As expected (Bergin & Bergin, 2009; Jacobsen & Hofmann, 1997), the results suggest that secure attachment contributes to positive aspects of school adjustment for children. Findings on the influence of insecure attachment must be considered in the context of children’s basal cortisol levels and their emotional reaction to maternal distress, which may clarify inconsistencies in the literature regarding why some insecure children have poor academic outcomes while others do not (Weinfield et al, 1999) and advance our under-standing of the individual differences in children’s stress processes that contribute to adjustment.

Generally, high basal cortisol levels appear to be especially problematic for insecure children who are also experiencing emotional distress to family relations. Children who have high basal levels of cortisol and also reported being emotionally distressed by the family stressor had less positive attitudes toward school and lower levels of parent-reported scholastic competence, interestingly unless also insecure. However, for children who are insecure and exhibiting high cortisol levels, the ability to suppress emotional experience in the family context appears to buffer against the deleterious effects on both school outcomes. This is an important finding, especially given that in this community sample these children actually had the highest reports of parent-reported scholastic competence. Moreover, in the context of children’s positive attitudes toward school, low cortisol levels were also problematic for insecure children experiencing emotional distress to family relations. This is consistent with previous findings suggesting that diminished cortisol levels may be associated with adjustment difficulties (Gunnar et al, 1996). It may be that, in the context of chronic family stressors, children’s hyper-reactivity results in diminished stress hormone levels as physiological systems adapt over time.

As expected, children with mid-range basal levels of cortisol also appeared to have higher levels of parent-reported scholastic competence and more positive attitudes toward school overall. In certain contexts children with both low and high cortisol levels had poorer levels of parent-reported scholastic competence and less positive attitudes toward school. Thus it is important to consider both high and low levels of cortisol with regard to understanding negative effects on children’s adjustment. These findings also highlight the importance of examining multiple child processes in social contexts to advance our understanding of the role of children’s stress hormones in influencing adjustment (Granger & Kivlighan, 2003).

Interestingly, there was one context in which children experienced multiple risks, including insecure attachment and high basal cortisol levels, that was associated with positive school adjustment outcomes. Specifically, children who did not experience emotional distress in response to family stress had high levels of parent-reported scholastic competence. This finding indicated that this context was associated with even higher levels of parent-reported scholastic competence than in secure children, suggesting resilient processes in the context of risk, as these children appear to suppress or regulate their emotional experience. Perhaps not becoming emotionally distressed in the context of family stress indicates a sense of security in other family relationships, such as security about the interparental relationship, which may promote positive adjustment (Cummings et al, 2006). Children’s security about the stability of the interparental unit has been associated with positive adjustment in multiple domains. This may protect against the anxiety or emotional difficulties that tend to preoccupy insecure children and hinder their abilities to attend to and succeed in school.

Alternatively, this unexpected finding may be due to other considerations. Notably, children’s parent-reported scholastic competence was reported by parents, and research has indicated that insecure-avoidant individuals may report unusually high levels of functioning (Cassidy & Shaver, 2008). This unexpected relationship between parent-reported high levels of scholastic competence among insecure children who are not reporting emotional distress but exhibiting high levels of cortisol should be further examined, using other reporters’ perspectives of functioning, such as teacher report of scholastic competence or objective indicators of academic performance. While scholastic competence levels may be high for the children, this study did not actually examine academic performance and, while competence appears high, it is possible that these insecure children with high cortisol levels may not actually be performing well in school. Further research to disentangle these specific outcomes processes is warranted.

While generally our findings are consistent with previous research (Bus & van IJzendoorn, 1988; Gunnar et al, 1996; Sroufe et al, 1983) our findings also highlight the important role of emotional experience in the association between attachment and school-related outcomes. Overall, the findings supported that there were few differences among children who were securely attached with mothers, regardless of their basal cortisol levels or emotional distress to a family stressor; securely attached children had relatively high levels of parent-reported scholastic competence and positive attitudes toward school. This finding is not surprising, given the expectation that a secure attachment relationship may foster children’s ability to regulate distress appropriately, such that even in the context of becoming emotionally distressed the secure child is able to use their resources to regulate this distress.

Interestingly, future research should examine cortisol reactivity or recovery from distress in this context beyond basal cortisol levels, to understand recovery from emotional family stressors during this period and to understand relations with school adjustment. Secure children who experienced high cortisol levels but did not acknowledge emotional distress during the family stressor had lower levels of parent-reported scholastic competence; this nuanced finding should be further examined. However, overall these findings, which provide support for secure attachment as a protective factor for school adjustment, advance our understanding of the development of children’s school attitudes and scholastic competence.

The study also has important implications for SMH interventions. Focusing on strengthening a supportive parent–child relationship and fostering attachment security may be an important component to be considered in interventions targeting improvement in psychosocial outcomes in school-based services. The reactions and responses that children exhibit in the context of family stress may also influence their stress and coping regulatory processes in other contexts outside the family (Cummings et al, 2000). Understanding differences in children’s experience in the family context, including children’s basal cortisol, emotional responses, and attachment security, can therefore influence understanding of children’s stress management in peer and school contexts. School mental health services aimed at reducing problem behaviors may focus on increasing students’ regulatory capacities, which may influence stress responses in multiple contexts, including extending to children’s confrontation with family stress. Currently, mental health prevention programs that target improvement in family processes to reduce children’s maladjustment focus on providing children with resources for coping in the family, and for managing stress in the peer and school context (Cummings & Davies, 2010; Cummings et al, 2008). School mental health prevention and intervention programs may also focus on providing children with skills for managing stress in the family context as well. Given the invaluable opportunity SMH services provide for young people in accessing resources and improving psychosocial difficulties, this setting may also prove useful in equipping young people with skills advantageous in other contexts.

Thus, this study has many strengths, including the examination of the stress hormone cortisol in the social context of the mother-child relationship to understand associations between attachment and school-related outcomes. The generalizability of the findings of this study are limited, because the children and families were from a relatively well-functioning sample and in an experimental setting. The findings must also be interpreted with caution because relationships are cross-sectional. Future longitudinal examination of these processes is warranted. Attachment security was examined with regard to overall secure versus insecure children, but there are differences in the patterns that insecure children exhibit, and further examination of these differences is warranted. Different patterns for coping with maladaptive caregiving may result in different physiological stress processes. Further examination of relations among specific insecure patterns may further our understanding of how these stress and emotion processes contribute to children’s school adjustment.

Still, the study is important in contributing to understanding the influence of children’s attachment on school adjustment, with particular focus on basal cortisol levels and the experience of emotional distress in family contexts. Notably, the study also contributes to the growing literature on the importance of examining the role of hormones in behavior, suggesting complex associations underlying the influence of hormones and behaviors on each other (Loman & Gunnar, 2010; Nachmias et al, 1996; Tarullo & Gunnar, 2006). Finally, the study strengthens previous findings with regard to supporting differences in the effect of attachment on children’s school adjustment in the context of considering other family systems (Jacobsen & Hofmann, 1997), suggesting that in the context of insecurity and maladaptive cortisol levels, children may still exhibit positive adjustment if they are able to manage emotional distress effectively in response to other family contexts. Further examination of these relations underlying links between insecurity and school adjustment will advance our understanding of how these socio-emotional processes contributing to school performance and functioning are related to physiological functioning.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the NIMH (R01 MH57318) awarded to Patrick Davies and E Mark Cummings.

Contributor Information

E Mark Cummings, University of Notre Dame, USA.

Patrick T Davies, University of Rochester, USA.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS. Object relations, dependency, and attachment: a theoretical review of the infant–mother relationship. Child Development. 1969;40:969–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of Attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bergin C, Bergin D. Attachment in the classroom. Educational Psychology Review. 2009;21:141–70. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Johnson D, Granger D. Testosterone and men’s depression: the role of social behavior. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:130–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1969. Attachment and Loss. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Ellis BJ. Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary-developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:271–301. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray JH, Maxwell SE, Cole D. Multivariate statistics for family psychology research. Journal of Family Psychology. 1995;9:144–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bus AG, Van IJzendoorn MH. Mother-child interactions, attachment, and emergent literacy: a cross-sectional study. Child Development. 1988;59:1262–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Marvin RS with the MacArthur Working Group on Attachment. Unpublished manuscript. University of Virginia; 1992. Attachment organization in three- and four-year olds: procedures and coding manual. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Shaver PR. Handbook of Attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 2. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Marital Conflict and Children: An emotional security perspective. New York & London: The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Campbell SB. Developmental Psychopathology and Family Process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. New York: Guilford; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Faircloth BF, Mitchell PM, Cummings JS, Schermerhorn AC. Evaluating a brief prevention program for improving marital conflict in community families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:193–202. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Kouros CD, Papp LM. History of marital aggression, everyday interparental conflict, and children’s responding to everyday conflicts. European Psychologist. 2007;12:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Schermerhorn AC, Davies PT, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings JS. Interparental discord and child adjustment: prospective investigations of emotional security as an explanatory mechanism. Child Development. 2006;77(1):132–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M, Skinner ML. Family, school, and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:172–80. [Google Scholar]

- Granger DA, Kivlighan KT. Integrating biological, behavioral, and social levels of analysis in early child development: progress, problems, and prospects. Child Development. 2003;74:1058–63. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granot D, Mayseless O. Attachment security and adjustment to school in middle childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2001;25:530–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR. Psychoendocrine studies of temperament and stress in early childhood: expanding current models. In: Bates JE, Wachs TD, editors. Temperament: Individual differences at the interface of biology and behavior. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Brodersen L, Nachmias M, Buss K, Rigatuso J. Stress reactivity and attachment security. Developmental Psychobiology. 1996;29:191–204. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2302(199604)29:3<191::AID-DEV1>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development. 1982;53:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen T, Hofmann V. Children’s attachment representations: longitudinal relations to school behavior and academic competency in childhood and adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:703–10. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Cole HE, Ferenz-Gillies R, Fleming WS, Gamble W. Attachment and emotion regulation during mother–teen problem solving: a control theory analysis. Child Development. 1993;64:231–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer BJ, Ladd GW. Peer victimization: manifestations and relations to school adjustment in kindergarten. Journal of School Psychology. 1996;34:267–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Burgess KB. Do relational risks and protective factors moderate the linkages between childhood aggression and early psychological and school adjustment? Child Development. 2001;72:1579–601. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Price JM. Predicting children’s social and school adjustment following the transition from preschool to kindergarten. Child Development. 1987;58:1168–89. [Google Scholar]

- Loman MM, Gunnar MR. Early experience and the development of stress reactivity and regulation in children. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;34(6):867–976. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M. Exploration, play, and cognitive functioning related to infant–mother attachment. Infant Behavior and Development. 1983;6:167–74. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Cassidy J. Categories of response to reunion with the parent at age 6: predictable from infant attachment classifications and stable over a 1-month period. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:415–26. [Google Scholar]

- Moss E, St-Laurent D. Attachment at school age and academic performance. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:863–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray-Harvey R, Slee PT. Family stress and school adjustment: predictors across the school years. Early Child Development and Care. 1998;145:133–49. [Google Scholar]

- Nachmias M, Gunnar M, Mangelsdorf S, Parritz RH, Buss K. Behavioral inhibition and stress reactivity: the moderating role of attachment security. Child Development. 1996;67:508–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA. Neural plasticity and human development: the role of early experience in sculpting memory systems. Developmental Science. 2000;3:115–30. [Google Scholar]

- Roeser RW, Eccles JS, Strobel KR. Linking the study of schooling and mental health: selected issues and empirical illustrations at the level of the individual. Educational Psychologist. 1998;33:153–76. [Google Scholar]

- Shamir H, Cummings EM, Davies PT, Goeke-Morey MC. Children’s reactions to marital conflict resolution in Israel and in the United States. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2005;5:371–86. [Google Scholar]

- Spangler G, Grossman KE. Biobehavioral organization in securely and insecurely attached infants. Child Development. 1993;64:1439–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Fox NE, Pancake VR. Attachment and dependency in developmental perspective. Child Development. 1983;54:1615–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Rutter M. The domain of developmental psychopathology. Child Development. 1984;55:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Waters E. Attachment as an organizational construct. Child Development. 1977;48:1184–99. [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple ML, Davies PT, Winter MA, Cummings EM, Schermerhorn A. Interparental conflict and children’s school adjustment: the explanatory role of children’s internal representations of interparental and parent–child relationships. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1678–90. doi: 10.1037/a0013857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarullo AR, Gunnar MR. Child maltreatment and the developing HPA axis. Hormones and Behavior. 2006;50:632–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinfield NS, Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson EA. The nature of individual differences in infant–caregiver attachment. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and clinical applications. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]