Abstract

In the present study, we examined the sequential changes of diethylnitrosamine (DEN)-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in Wistar rats. After 14 weeks of DEN treatment, hyperplastic nodules developed as a consequence of the appearance of renewed hepatocytes, degenerated hepatocytes, oval cells and fibrotic changes. Total bilirubin and alanine aminotransferase levels were significantly higher in the DEN group compared to the control group throughout the experimental period. Our data may prove beneficial to future analyses of chemopreventive compounds during various stages of hepatocarcinogenesis in rats.

Keywords: diethylnitrosamine, hepatocellular carcinoma, Wistar rats

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignancies in the world, and is the third-leading cause of mortality from cancer (1,2) and the fifth most prevalent malignancy worldwide (3). Treatment options for HCC include liver resection, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and molecular targeted therapies, such as sorafenib (4). In spite of the advances in the treatment and early detection of HCC, the prognosis of patients with HCC is still unsatisfactory and HCC remains an intractable disease. Experimental animal models of HCC are feasible for investigating novel chemopreventive remedies for patients with chronic liver diseases who are at high risk of developing HCC. Although a number of HCC models have been generated, including hepatitis C virus (HCV) core transgenic mice (5), Pten-deficient mice (6) and activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID)-transgenic mice (7), these models require intricate genetic manipulation.

Diethylnitrosamine (DEN) is present in tobacco smoke, water, cured and fried meals, agricultural chemicals, cosmetics and pharmaceutical agents (8) and is commercially available for experimental use. DEN is an established powerful hepatocarcinogen in rats, which possibly works by altering the DNA structure, forming alkyl DNA adducts, and inducing chromosomal aberrations and micronuclei in the liver (9,10). It has also been reported that oxidative stress plays a pivotal role during carcinogenesis (11). Although a single injection of DEN followed by partial hepatectomy coupled with 2-acetylaminofluorene (2-AAF) is an established procedure for developing HCC in rodents (12), the sequential administration of DEN for a number of weeks has also been employed for inducing HCC (13,14). However, sequential changes in the liver in DEN-based hepatocarcinogenesis have not been clarified. In this study, we analyzed DEN-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in rats by chronologically evaluating biological parameters and liver tissues following treatment with DEN.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

DEN and an anti-β-actin antibody were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Pentobarbital was purchased from Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Antibodies against proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and glutathione S-transferase placental type (GST-P) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and Assay Designs, Inc. (Ann Arbor, MI, USA), respectively. Secondary anti-mouse and anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP) antibodies for western blot analysis were obtained from GE Healthcare Ltd. (Buckinghamshire, UK). All other chemicals and solvents used in this study were of analytical grade.

Animals, treatments and tissue collection

Male Wistar rats weighing ~200 g were purchased from Japan SLC, Inc. (Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan). All animals received humane care and the experimental protocols were approved by the Tottori University Animal Ethics Committee. The animals were housed two per cage with rice husks for bedding in an air-ventilated room under a 12-h light/dark cycle with a constant temperature (22°C) and humidity (55%). The animals were allowed access to food and tap water ad libitum during the experiment. The rats were randomly divided into two groups and intraperitoneally injected with DEN (40 mg/kg body weight) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (DEN groups, 4 rats were assigned to each treatment week) or PBS (control groups, 2 rats were assigned to each treatment week) weekly for 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14 weeks (Fig. 1). Body weights were monitored weekly throughout the experimental period. One week following the last treatment, the rats were sacrificed under anesthesia by pentobarbital. Blood samples were collected via cardiac puncture and serum samples were stored at −30°C until analysis. Immediately after the livers were excised, they were weighed and divided into two sections for histological examination in 10% neutral buffered formalin and for protein extraction at −80°C.

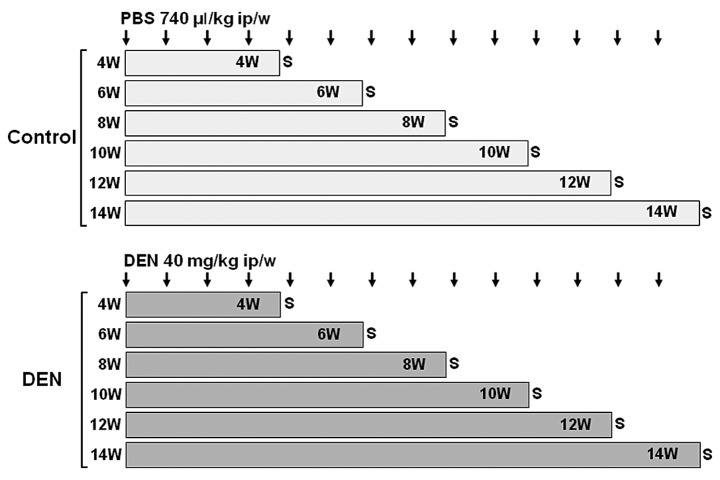

Figure 1.

Experimental schedules of Wistar rats. Male Wistar rats were randomly divided into two groups: DEN and control groups. Rats in the DEN group were intraperitoneally injected with 40 mg/kg body weight of DEN dissolved in PBS for 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14 weeks. Four rats were assigned to each treatment week. Rats in the control group were intraperitoneally injected with 740 μl/kg body weight of PBS for 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14 weeks. Two rats were assigned to each treatment week. DEN, diethylnitrosamine; ip, intraperitoneal; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; S, sacrifice; W, weeks.

Measurement of serum transaminase and total bilirubin

Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and total bilirubin levels were measured at SRL, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan).

Total protein preparation and western blotting

The liver samples were mashed with a BioMasher (Nippi Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and lysed in radioimmune precipitation (RIPA) buffer (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA, USA) supplemented with 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and a protease inhibitor mixture tablet (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) for 10 min on ice. Total protein samples (5 μg) were separated on a sodium lauryl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel (PAGE) (SuperSep, Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore Corp.). After the membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat milk (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) in TBST (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0, and 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature, they were probed with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, washed three times in TBST, and incubated with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit HRP antibody in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. After the signals were developed with a chemiluminescence solution (ECL, GE Healthcare Ltd.), they were visualized and quantified using an image analyzer (LAS-3000 mini, Fujifilm Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

The rat liver tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and paraffin embedded. For histologic analysis, serial sections (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Neoplastic nodules and HCC were classified on the basis of Japanese criteria (15). Degenerated hepatocytes, oval cells, renewed hepatocytes and hyperplastic nodules were quantified as follows: grade 1 when <5%, grade 2 when 5–50%, and grade 3 when >50% in the field. For immunohistochemistry with the PCNA and GST-P antibodies, Histofine® Simple Stain Rat MAX PO was employed (Nichirei Biosciences Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Briefly, after routine dewaxing with xylene and hydration through a graded ethanol series, the sections were incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide solution for 15 min at room temperature to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. After washing in gently-running tap water, the sections were rinsed with PBS, and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After rinsing with PBS, the sections were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody for 30 min at room temperature. The peroxidase activity was developed with DAB solution (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA). Counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin. The PCNA labeling indices were represented as the percentage of positively stained nuclei by counting 1,000 cells in the field at x400 magnification. The GST-P-positive area was measured on images captured by a charge coupled device (CCD) camera on a Windows® computer.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as the means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed by the unrelated t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test. A p-value <0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Relative liver weight and biological parameters

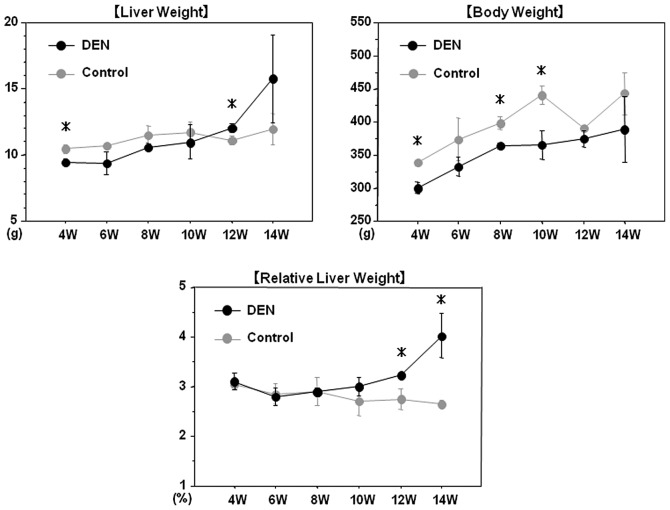

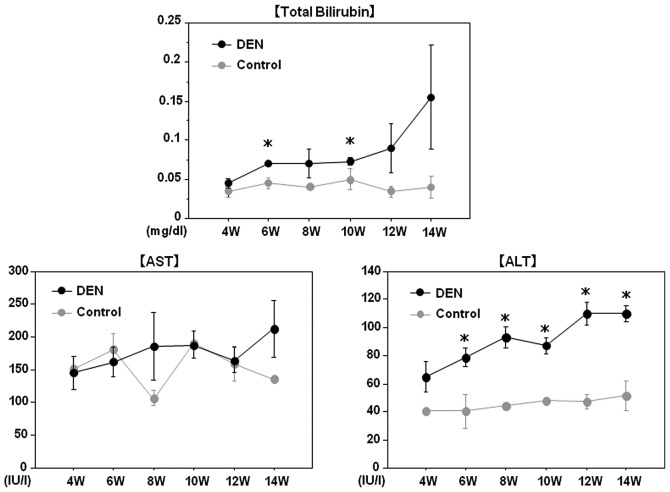

All rats survived throughout the experimental period. Chronological changes in the liver and body weights are demonstrated in Fig. 2. After 12 and 14 weeks of the treatment, the relative liver weight (liver weight/body weight) in the DEN group was significantly higher than that in the control group, presumably due to the development of liver tumors in the DEN group. Although serum AST levels did not differ between the two groups, total bilirubin and ALT levels were significantly higher in the DEN group than in the control group throughout the experimental period, possibly reflecting liver injury induced by DEN (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Chronological changes in the liver and body weights. Chronological changes in the liver and body weights of the rats in the DEN and control groups are demonstrated. After 12 and 14 weeks of the treatment, the relative liver weight (liver weight/body weight) in the DEN group was significantly higher than that in the control group. DEN, diethylnitrosamine; W, weeks. *p<0.05 (unrelated t-test).

Figure 3.

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and total bilirubin levels. Changes in serum ALT, AST and total bilirubin levels during the experimental period are demonstrated. Although serum AST levels did not differ between the two groups, total bilirubin and ALT levels were significantly higher in the DEN group than in the control group throughout the experimental period. DEN, diethylnitrosamine; W, weeks. *p<0.05 (unrelated t-test).

Histological examinations

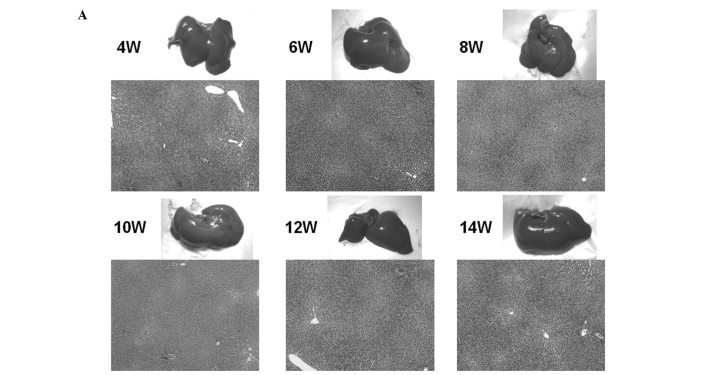

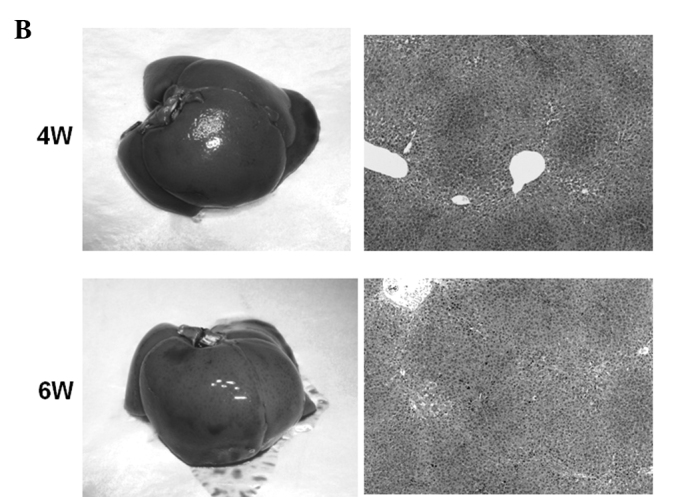

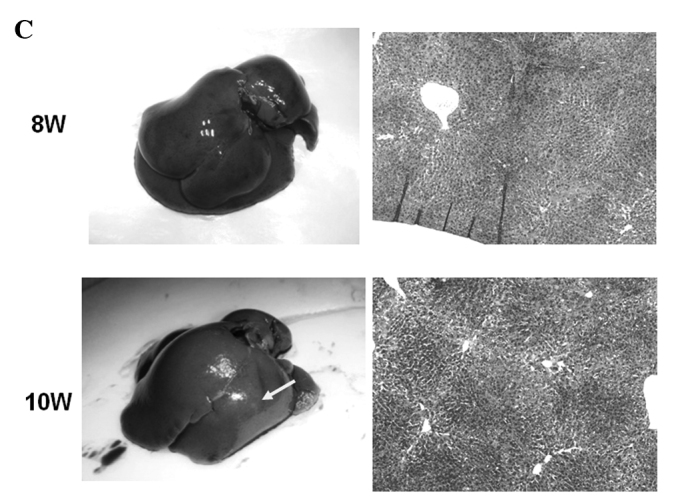

Macroscopic and microscopic features of the liver were chronologically examined. In the control group, as expected, no liver tumors were observed throughout the experimental period (Fig. 4A). In the DEN group, no significant gross lesions were observed following 8 weeks of the treatment. However, following 10 weeks of the treatment, white nodules were macroscopically noted, the number of which increased thereafter (Fig. 4B–D). Microscopic analysis revealed that renewed hepatocytes started to appear after 4 weeks of the treatment, and degenerated hepatocytes, oval cells and fibrotic changes were observed after 6 weeks of the treatment (Fig. 4E). After 12 weeks of the DEN treatment, hyperplastic nodules developed (Fig. 4D). However, no definite HCC was observed throughout the experimental period. Quantified histological changes following the DEN treatment are summarized in Table I.

Figure 4.

Macroscopic and microscopic features of the liver. Macroscopic and microscopic features of the liver in (A) the control group and (B–E) the DEN group are chronologically demonstrated. (A) Livers in the control group appeared normal throughout the experimental period. Original maginification, x100. (B and C) After 10 weeks of the DEN treatment, white nodules started to appear. Renewed hepatocytes appeared after 4 weeks, and degenerated hepatocytes, oval cells and fibrotic changes appeared after 6 weeks of the treatment (original maginification, x100). (D) After 12 weeks of the DEN treatment, a number of white nodules were observed. Histological analysis revealed that these were hyperplastic nodules (original maginification, x100). (E) Regenerated hepatocytes (single arrow) and renewed hepatocytes (double arrows) observed after 6 weeks of the DEN treatment are demonstrated in the top image (original maginification, x400). Oval cells observed after 10 weeks of the DEN treatment are demonstrated in the bottom image (original maginification, x400). DEN, diethylnitrosamine; W, weeks.

Table I.

Summary of quantified histological changes after the DEN treatment.

| Group | Weeks | No. | Degenerated hepatocytes | Oval cells | Renewed hepatocytes | Hyperplastic nodules | HCC | Fibrosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ||||||||

| 4 | 301 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 302 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 6 | 303 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 304 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 8 | 305 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 306 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 10 | 307 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 308 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 12 | 309 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 310 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 14 | 311 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 312 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| DEN | ||||||||

| 4 | 501 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 502 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 503 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 504 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 6 | 505 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 506 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 507 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 508 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 8 | 509 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 510 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 511 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 512 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10 | 513 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 514 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 515 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 516 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 12 | 517 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| 518 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| 519 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 520 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 14 | 521 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| 522 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | ||

| 523 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | ||

| 524 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

0, none; 1 <5%; 2, <50%; 3, ≥50%. DEN, diethylnitrosamine; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

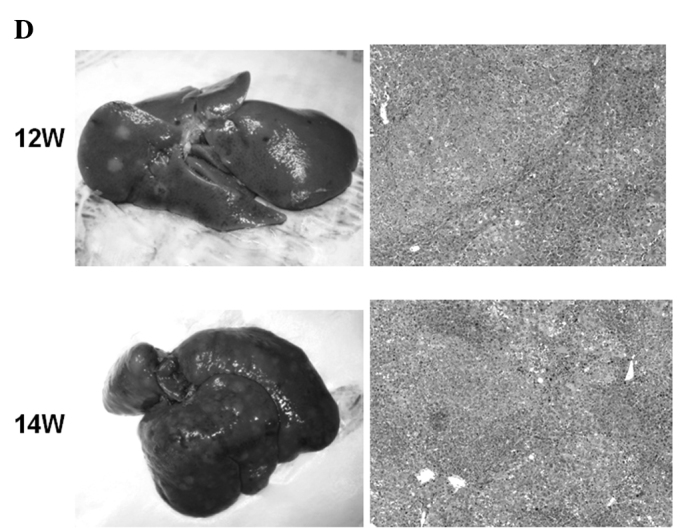

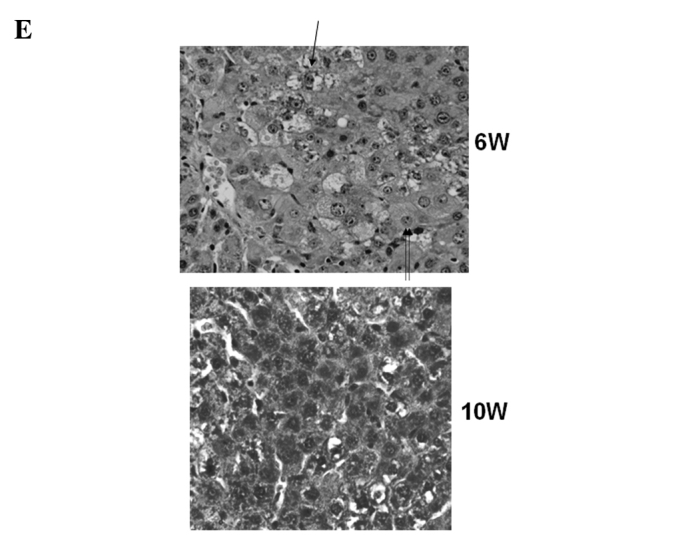

Expression levels of GST-P and PCNA

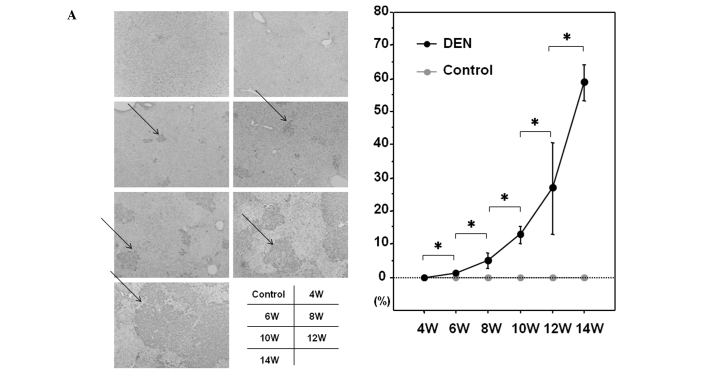

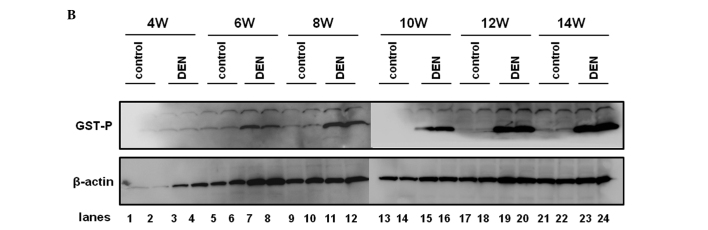

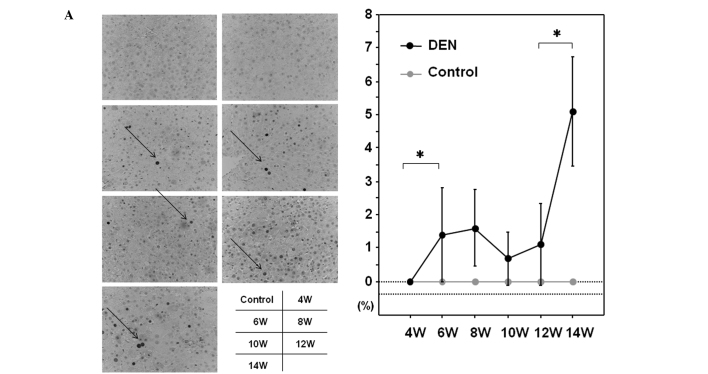

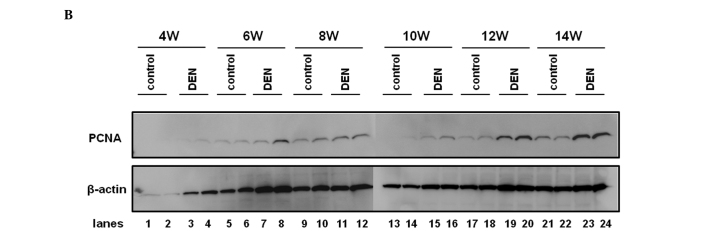

Among the GSTs, a family of detoxification enzymes that catalyze the conjugation of glutathione with a large number of carcinogens, GST-P has been used as a reliable tumor marker for experimental hepatocarcinogenesis in the rat (16). PCNA is an essential regulator of the cell cycle, whose expression has been a useful tool for studying cell proliferation, including cell proliferation in the liver (17). We sought to investigate the expression levels of GST-P and PCNA during hepatocarcinogenesis induced by DEN. As expected, the control liver did not express a significant amount of GST-P when evaluated by immunohistochemical or western blot analysis (Fig. 5A and B). GST-P-positive foci started to appear after 6 weeks of the DEN treatment and the expression levels of GST-P were significantly increased thereafter throughout the experimental period (Fig. 5A and B). The expression levels of PCNA were sequentially increased after the treatment with DEN when analyzed by immunohistochemical and western blot analysis (Fig. 6A and B).

Figure 5.

GST-P expression in the liver. Expression levels of GST-P were chronologically analyzed by (A) immunohistochemical analysis and (B) western blot analysis. (A) Representative sections immunostained with the anti-GST-P antibody are demonstrated. GST-P-positive foci are indicated by arrows. (B) Protein samples extracted from control and DEN-treated livers for 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14 weeks were utilized for western blot analysis with the anti-GST-P antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody as the internal control. Original maginification, x100. DEN, diethylnitrosamine; GST, glutathione S-transferase; W, weeks. *p<0.05 (Mann-Whitney U test).

Figure 6.

PCNA expression in the liver. PCNA expression levels were chronologically analyzed by (A) immunohistochemical analysis and (B) western blot analysis. (A) Representative sections immunostained with the anti-PCNA antibody are demonstrated. PCNA-positive cells are indicated by arrows. (B) Protein samples extracted from the control and DEN-treated livers for 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14 weeks were utilized for western blot analysis with the anti-PCNA antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody as the internal control. Original maginification, x100. DEN, diethylnitrosamine; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; W, weeks. *p<0.05 (Mann-Whitney U test).

Discussion

DEN-based HCC models have been utilized for investigating the beneficial effects of anti-carcinogenic compounds in vivo. Since the sequential changes in the liver following the administration of DEN have not been clarified, we evaluated them by sequentially examining biological parameters and liver tissues. After 14 weeks of DEN treatment, hyperplastic nodules developed as a consequence of the appearance of renewed hepatocytes, degenerated hepatocytes, oval cells and fibrotic changes. Unfortunately, we did not observe the rats beyond 14 weeks. It is plausible that longer treatment with DEN could lead to the development of HCC. In addition, since we did not investigate the molecular mechanisms involved in the histological changes following treatment with DEN in this study, future intensive studies are necessary to unveil these issues.

Compounds which have potential chemopreventive effects on the liver include acyclic retinoid (ACR), caffeine, capsaicin, cinnamaldehyde, curcumin, diallyl sulfide (DAS), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), genistein, lycopene, resveratrol, silymarin and sulforaphane (SFN) (18). Since the anti-hepatocarcinogenic effects of these compounds have become known mainly from in vitro experimental studies and epidemiology, hepatocarcinogenic models in rats would be useful for testing these compounds in vivo. As shown in the present study, the sequential analysis of DEN-induced hepatocarcinogenesis may be valuable for investigating the effects of compounds at variable stages of hepatocarcinogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr. Yujirou Ikuta for his technical assistance.

Abbreviations:

- ALT,

alanine aminotransferase;

- AST,

aspartate aminotransferase;

- DEN,

diethylnitrosamine;

- GST,

glutathione S-transferase;

- H&E,

hematoxylin and eosin;

- HCC,

hepatocellular carcinoma;

- HCV,

hepatitis C virus;

- PBS,

phosphate-buffered saline;

- PCNA,

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

References

- 1.Bosch FX, Ribes J, Borras J. Epidemiology of primary liver cancer. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:271–285. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557–2576. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farazi PA, DePinho RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:674–687. doi: 10.1038/nrc1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen YC, Hsu C, Cheng AL. Molecular targeted therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: current status and future perspectives. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:794–807. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moriya K, Fujie H, Shintani Y, et al. The core protein of hepatitis C virus induces hepatocellular carcinoma in transgenic mice. Nat Med. 1998;4:1065–1067. doi: 10.1038/2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horie Y, Suzuki A, Kataoka E, et al. Hepatocyte-specific Pten deficiency results in steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinomas. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1774–1783. doi: 10.1172/JCI20513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takai A, Toyoshima T, Uemura M, et al. A novel mouse model of hepatocarcinogenesis triggered by AID causing deleterious p53 mutations. Oncogene. 2009;28:469–478. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Shahat M, El-Abd S, Alkafafy M, El-Khatib G. Potential chemoprevention of diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in rats: Myrrh (Commiphora molmol) vs. turmeric (Curcuma longa) Acta Histochem. 2011 Aug 25; doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2011.08.002. (E-pub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Rejaie SS, Aleisa AM, Al-Yahya AA, et al. Progression of diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatic carcinogenesis in carnitine-depleted rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1373–1380. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verna L, Whysner J, Williams GM. N-nitrosodiethylamine mechanistic data and risk assessment: bioactivation, DNA-adduct formation, mutagenicity, and tumor initiation. Pharmacol Ther. 1996;71:57–81. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(96)00062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayakumar S, Madankumar A, Asokkumar S, et al. Potential preventive effect of carvacrol against diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocellular carcinoma in rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011 Aug 31; doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1043-7. (E-pub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solt DB, Cayama E, Tsuda H, Enomoto K, Lee G, Farber E. Promotion of liver cancer development by brief exposure to dietary 2-acetylaminofluorene plus partial hepatectomy or carbon tetrachloride. Cancer Res. 1983;43:188–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chuang S-E, Cheng A-L, Lin J-K, Kuo M-L. Inhibition by curcumin of diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatic hyperplasia, inflammation, cellular gene products and cell-cycle-related proteins in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2000;38:991–995. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(00)00101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiota G, Harada K, Ishida M, et al. Inhibition of hepatocellular carcinoma by glycyrrhizin in diethylnitrosamine-treated mice. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:59–63. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Squire RA, Levitt MH. Report of a workshop on classification of specific hepatocellular lesions in rats. Cancer Res. 1975;35:3214–3223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakai M, Muramatsu M. Regulation of glutathione transferase P: a tumor marker of hepatocarcinogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:575–578. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alenzi FQ, El-Nashar EM, Al-Ghamdi SS, et al. Investigation of Bcl-2 and PCNA in hepatocellular carcinoma: relation to chronic HCV. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2010;22:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okano J, Fujise Y, Abe R, Imamoto R, Murawaki Y. Chemo-prevention against hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2011;4:185–197. doi: 10.1007/s12328-011-0227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]