The capsaicin or vanilloid receptor (VR) plays an important role in transducing thermal and inflammatory pain. The VR is a nonselective cation channel that possesses a high permeability to Ca2+ (PCa/PNa ratio ≈10, similar to that of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor), exhibits strong outward rectification, and desensitizes after repeated stimulation (tachyphylaxis) (1). Two types of VRs (VR1, VR-L) and a splice variant (VR.5′sv) have been cloned (2–4). Generally, VRs are thought to be distributed in peripheral sensory nerve endings and involved in the perception of noxious stimuli. The activation of VRs depolarizes the sensory nerve endings and evokes a train of action potentials that propagates to the spinal cord and brain. Mice lacking the VR1 gene have deficits in thermal- or inflammation-induced hyperalgesia but are sensitive to noxious heat, which largely confirms a role in certain modalities of nociception (5, 6). On the other hand, purinergic receptors (P2Y) also are expressed in nociceptive sensory nerve endings. They are either coupled directly to ion channels (ionotropic) or to the G protein-mediated production of second messengers (metabotropic). Seven ionotropic (P2X1–7) and six genuine metabotropic receptors (P2Y1,2,4,6,11,12) (from a total of 13 P2Y-like cDNA clones) have been cloned. The P2X3 subtype is exclusively expressed in the peripheral nerve endings (7, 8). Algesic properties of ATP are thought to occur by the activation of P2X receptors. Although the source for extracellular ATP is a debated issue, a number of possibilities have been suggested: (i) mechanical stimulation; (ii) activation of connexin hemichannels; (iii) synaptic vesicle exocytosis; (iv) tissue damage; and (v) from nerve endings after noxious stimulation (7, 9). Activation of P2X3 receptors by ATP is not a favorable means of nociception because ecto-nucleotidases rapidly metabolize ATP, and the time constants for desensitization (<100 ms) and recovery from desensitization (>20 min) are not ideal channel properties for effective propagation of pain signal (10). In accord with this notion, disruption of P2X3 receptors does not fully reduce the nociceptive behavior (11, 12).

Normal body temperature is a sufficient stimulus to activate vanilloid receptors. This reduced temperature threshold may contribute to certain forms of chronic pain.

In this issue of PNAS, Tominaga et al. (13) show that in human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells, stimulation of the endogenous metabotropic purinergic receptor P2Y1 enhances the sensitivity of the heterologously expressed VR1 to capsaicin, protons, and temperature in a protein kinase C (PKC)-dependent manner. To further substantiate these findings, the authors coexpressed M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors and VR1 and demonstrated that, when pretreated with acetylcholine, the VR response induced by capsaicin or protons was potentiated. Finally, a similar potentiation of VR response by ATP could be observed in neurons from dorsal root ganglia. The authors conclude that ATP-induced nociception is partly caused by a potentiation of the VR response. A particularly significant finding is that the threshold for heat activation decreased from 42°C to 35°C, which suggests that, under certain circumstances, normal body temperature is a sufficient stimulus to activate VRs. This reduced threshold may contribute to certain forms of chronic pain. Perhaps, as suggested by the authors, the P2Y1 receptor could be a molecular target for the development of novel therapeutic agents.

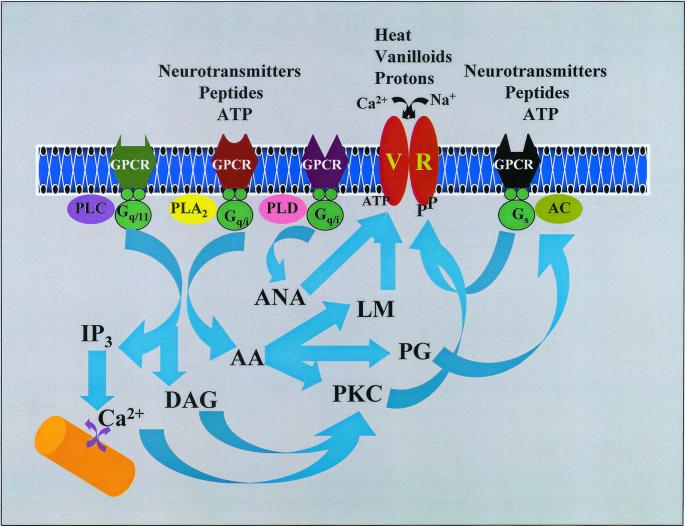

Fig. 1 shows the second-messenger pathways that converge to activate/sensitize the VRs. ATP via P2Y receptors modulates second-messenger cascades regulated by adenylate cyclase (AC), phospholipase C (PLC), phospholipase D (PLD), and phospholipase A2 (7, 8). In most cases P2Y receptors inhibit AC via Gi, however, P2Y receptors also can stimulate AC via Gs. Activation of PLC induces hydrolysis of phosphatidyl inositol bisphosphate to produce diacylglycerol and inositol trisphosphate (IP3). The diacylglycerol so produced activates PKC whereas the IP3 triggers Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Most P2Y receptors are coupled to Ca2+-sensitive (PKC-β, γ) or insensitive (PKC-ɛ, δ) forms of PKC. ATP effects on P2Y receptors also include activation of PLD. Interestingly, G protein receptors coupled to PLC invariably stimulate PLD activity as well. PLD catalyses the hydrolysis of N-arachidonyl phosphatidylethanolamine to produce anandamide, which in turn can directly activate VRs. Activation of phospholipase A2 produces arachidonic acid, which is subsequently metabolized via lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase pathways. The lipoxygenase metabolites hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid, and leukotriene B4 directly, but weakly, activate VRs (14), whereas cyclooxygenase metabolites (prostaglandin E2) potentiate the response of capsaicin by increasing cAMP levels (15). In addition, arachidonic acid can directly activate some PKC isoforms. VRs have a number of consensus phosphorylation sites that can be phosphorylated by protein kinases A, C, and G, Ca2+ calmodulin kinase, and tyrosine kinase. Activation of PKA strongly potentiates the VR response in neurons, which can be mimicked by prostaglandin E2 (15). PKC-mediated phosphorylation directly activates VRs (16) and strongly potentiates the capsaicin-induced (16) or heat-induced (17) responses. Particularly, PKC causes a near 10-fold increase in the membrane current induced by weak agonists, such as anandamide (16). Furthermore, the increases in intracellular calcium levels by IP3 or by other means (membrane depolarization or influx via a Ca2+ ionophore) also can potentiate heat-induced responses (likely mediated by VRs) (18). Interestingly, ligands that are coupled to both PLC and phospholipase A2, such as bradykinin, are potent agonists; second messengers from two different pathways synergistically induce maximal VR activity (16). It is also possible that two different agonists acting on separate signaling pathways can achieve a similar response. It is worth noting that in a recent study intracellular ATP binding to a Walker-type nucleotide-binding domain sensitized the VR response to capsaicin, suggesting that ATP could function as a coagonist in a fashion similar to glycine acting on the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (19).

Figure 1.

Known second-messenger pathways that modulate capsaicin or VRs (see text for details). GPCR, G protein-coupled receptors; PLA2, phospholipase A2; AC, adenylate cyclase; IP3, inositoltrisphosphate; DAG, diacylglycerol; LM, lipoxygenase metabolites; AA, arachidonic acid; ANA, anandamide; PG, prostaglandins; Gq/11, Gq/i, Gs, trimeric G proteins.

In support of the involvement of second-messenger pathways in pain signaling, targeted disruption of the PKC- or cAMP-dependent protein kinase gene has revealed their effects on selective modalities of pain. Deletion of PKC-ɛ gene reduced thermal and acid-induced hyperalgesia (20), whereas deletion of PKC-γ reduced neuropathic pain but preserved acute pain (21). Mice lacking type I regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase exhibited diminished inflammatory and nociceptive pain but preserved neuropathic pain (22).

Although VR is a molecular target for noxious stimuli, expression of VR in areas that are not likely to be exposed to noxious stimuli, especially the central nervous system, raises the possibility of VR functions other than in nociception. Recently VR1 has been shown to be expressed in neurons throughout the entire neuroaxis (including the cerebral cortex, limbic system, hypothalamus, substantia nigra, and cerebellum) (23). In the cardiovascular system (other than as nociceptors in the sensory C-fiber endings of the heart), activation of VRs release a variety of vasodilatory signaling molecules such as nitric oxide, calcitonin gene-related peptide, bradykinin, and histamine (1, 24). Putative endogenous VR ligands identified so far (anandamide and metabolites of arachidonic acid) are weak agonists and, therefore, are unlikely to induce a sizable response at the concentrations normally found in tissues (25). One way to overcome this would be to sensitize the receptor by phosphorylation. Previous studies have shown that the VR function could be modulated by phosphorylation or dephosphorylation (15, 16, 26). The findings by Tominaga et al. (13) are of significance in that a similar sensitization of VRs could be achieved by stimulating metabotropic receptors that leads to phosphorylation of VRs. As shown in this study, the temperature sensitivity of VRs is reduced; therefore, when the conditions are appropriate, normal body temperature could act as a primary stimulus. These findings have much broader implications, involving other metabotropic receptors. Modulation of VRs by these mechanisms is especially important in the central nervous system, where the role of these receptors is yet to be identified. Finally, not only does ATP-induced potentiation of VR response have a physiological relevance, but it also has an equal or greater significance in pathological conditions where extracellular ATP levels could be increased in a number of situations outlined above. As these receptors are highly calcium permeable, sensitizing the receptor via the activation of metabotropic receptors poses a danger of calcium overload leading to neuronal cell death, which is a daunting prospect in many neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments

I thank C. Grosman and C. L. Faingold for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine and National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

See companion article on page 6951.

References

- 1.Szallasi A, Blumberg P M. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:159–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caterina M J, Schumacher M A, Tominaga M, Rosen T A, Levine J D, Julius D. Nature (London) 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caterina M J, Rosen T A, Tominaga M, Brake A J, Julius D. Nature (London) 1999;398:436–441. doi: 10.1038/18906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schumacher M A, Moff I, Sudanagunta S P, Levine J D. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2756–2762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caterina M J, Leffler A, Malmberg A B, Martin W J, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz K R, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum A I, Julius D. Science. 2000;288:306–313. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis J B, Gray J, Gunthorpe M J, Hatcher J P, Davey P T, Overend P, Harries M H, Latcham J, Clapham C, Atkinson K, et al. Nature (London) 2000;405:183–187. doi: 10.1038/35012076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vassort G. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:767–806. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burnstock G. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:182–188. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fields D R, Stevens B. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;23:625–633. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCleskey E W, Gold M S. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:835–856. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cockayne D A, Hamilton S G, Zhu Q M, Dunn P M, Zhong Y, Novakovic S, Malmberg A B, Cain G, Berson A, Kassotakis L, et al. Nature (London) 2000;407:1011–1015. doi: 10.1038/35039519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Souslova V, Cesare P, Ding Y, Akopian A N, Stanfa L, Suzuki R, Carpenter K, Dickenson A, Boyce S, Hill R, et al. Nature (London) 2000;407:1015–1017. doi: 10.1038/35039526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tominaga M, Wada M, Masu M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6951–6956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111025298. . (First Published May 22, 2001; 10.1073/pnas.111025298) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwang S W, Cho H, Kwak J, Lee S Y, Kang C J, Jung J, Cho S, Min K H, Suh Y G, Kim D, Oh U. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6155–6160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopshire J C, Nicol G D. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6081–6092. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06081.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Premkumar L S, Ahern G P. Nature (London) 2000;408:985–990. doi: 10.1038/35050121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cesare P, Moriondo A, Vellani V, McNaughton P A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7658–7663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kress M, Guenther S. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:2612–2619. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.6.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwak J, Wang M H, Hwang S W, Kim T Y, Lee S Y, Oh U. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8298–8304. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08298.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khasar S G, Lin Y H, Martin A, Dadgar J, McMahon T, Wang D, Hundle B, Aley K O, Isenberg W, McCarter G, et al. Neuron. 1999;24:253–260. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80837-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malmberg A B, Chen C, Tonegawa S, Basbaum A I. Science. 1997;278:279–283. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malmberg A B, Brandon E P, Idzerda R L, Liu H, McKnight G S, Basbaum A I. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7462–7470. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07462.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mezey E, Toth Z E, Cortright D N, Arzubi M K, Krause J E, Elde R, Guo A, Blumberg P M, Szallasi A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3655–3660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060496197. . (First Published March 21, 2000, 10.1073/pnas.060496197) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zygmunt P M, Petersson J, Andersson D A, Chuang H, Sorgard M, Di Marzo V, Julius D, Hogestatt E D. Nature (London) 1999;400:452–457. doi: 10.1038/22761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szolcsanyi J. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:203–204. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01484-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Docherty R J, Yeats J C, Bevan S, Boddeke H W. Pflügers Arch. 1996;431:828–837. doi: 10.1007/s004240050074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]