Abstract

For advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, the only treatment option is palliative therapy, with the aim of prolonging overall survival and improving disease-related symptoms and quality of life (QOL). However, to date, the effect of palliative care on QOL has not yet been thoroughly examined, and there has been no meta-analysis of previous studies reporting QOL outcomes following palliative care. We consider that it is important to evaluate not only survival and/or response rates, but also QOL in patients with advanced NSCLC receiving palliative chemotherapy. The aim of the present study was to obtain useful information for the selection of suitable chemotherapy regimens for advanced NSCLC patients, taking into consideration QOL, and to demonstrate the importance of QOL assessments during treatment. We performed a meta-analysis of QOL outcomes following treatments that compared carboplatin- to cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Trials were eligible for analysis if they had compared carboplatin- to cisplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC patients who had not received prior chemotherapy, and if these studies reported QOL data. In the six trials eligible for analysis, 2,405 patients were randomized to receive cisplatin-based or carboplatin-based chemotherapy. The patients who received carboplatin-based chemotherapy had higher global QOL and less severe symptoms than those who received cisplatin-based chemotherapy. The survival rate, which was the primary outcome in clinical trials, and the response rate did not differ significantly between the two treatment groups. It is important to evaluate QOL in addition to the survival and response rates for advanced NSCLC, particularly when the treatment is palliative.

Keywords: palliative care, quality of life, meta-analysis, advanced non-small cell lung cancer, chemotherapy

Introduction

Worldwide, the most common type of cancer in terms of incidence and mortality is that of the lung (1). Among lung cancer cases, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 80% (2), and approximately 50% of such patients are diagnosed at the advanced or metastatic stage of the disease (3). With regard to treatment strategies for NSCLC, a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy is currently used for locally advanced disease, and chemotherapy alone is, at present, the best therapeutic option for patients with metastasis (4). A platinum-based regimen is appropriate for selected patients who have a good performance status, with both unresectable, locally-advanced and metastatic NSCLC (5).

For advanced NSCLC patients, the only treatment option is palliative therapy, with the aim of prolonging overall survival and improving disease-related symptoms and quality of life (QOL) (3). Clinicians working with patients suffering from inoperable lung cancer, striving to achieve the best QOL, should intervene to enhance significant QOL - from diagnosis, during the disease trajectory and in the bereavement phase (6). Thus, the QOL measurement is an important aspect of palliative care (7), both for patients and clinicians. The US Food and Drug Administration welcomes the opportunity to explore, with investigators, the use of QOL instruments in the design of cancer clinical trials (8). Harper et al noted that QOL assessment was an important component of numerous newer trial protocols, but was often given little weight when decisions were being made regarding the best treatment when comparing differences in survival (9). Previous meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), comparing carboplatin- to cisplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC, reported on survival, response rate and toxicity. However, there has been no meta-analysis of previous studies reporting QOL outcomes following such palliative treatment. We consider that it is important to evaluate not only survival or the response rate, but also the QOL of patients with advanced NSCLC who received palliative chemotherapy.

We performed a systematic literature review and a meta-analysis of QOL outcomes in studies comparing carboplatin- to cisplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced NSCLC, and confirmed whether results of the survival and response rates were similar to those in previous meta-analyses (10–12). The results of this study are expected to provide useful information for the selection of suitable chemotherapy regimens for advanced NSCLC patients, taking into consideration QOL.

Materials and methods

Study design

Systematic literature review and meta-analysis.

Search for trials

Trials were identified by an electronic search of the PubMed database and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) database until April 30, 2010. Search terms were as follows: ‘non-small cell lung cancer’, ‘NSCLC’, ‘carcinoma, non-small-cell-lung’ (MeSH), ‘drug therapy’ (MeSH), ‘cisplatin’ (MeSH) and ‘carboplatin’ (MeSH). Initially, searches were limited to English language publications of RCTs in humans. There was no limitation on the year of publication.

Selection of trials

Trials were eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis if they compared carboplatin- to cisplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with pathologically confirmed, advanced NSCLC, who had not received prior chemotherapy. They were also included if they reported QOL data using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) (13) or the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) (14), which are two of the most popular instruments used with cancer patients. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selection of trials are shown in Table I. The trials were then hand-searched according to these inclusion and exclusion criteria. When an RCT was reported in more than one study, only one study was included in the analysis. With regard to QOL data, articles were required to provide longitudinal assessment of QOL data, as well as explicit data (e.g., mean, median, p-value). Authors of all identified trials were asked for data confirmation by e-mail.

Table I.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria of selected trials.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| To be a randomized controlled clinical trial | To be a randomized phase II or I trial |

| To be an English publication | To be early stage |

| To be a randomized phase III trial | To be not NSCLC |

| To be a trial enrolling advanced NSCLC patients who have not received prior chemotherapy | To be a trial comparing the outcomes with a historical arm or literature data |

| To be a trial comparing carboplatin-based to cisplatin-based chemotherapy | To be a trial not reporting adequate information about randomization process in methods or results sections |

| To be a trial not reporting QOL data by using EORTC QLQ C30 | |

| To be a trial not reporting adequate information about the clinical assessment of the main outcomes of the trial | |

NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; QOL, quality of life; EORTC, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer.

Data extraction

Among the QOL scales, we focused on global QOL and the nine major symptom domains (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea and financial difficulties) that were most often assessed across studies. We used only QOL data collected at baseline and during the period from 12 to 17 weeks following the start of treatment due to the observation of the treatment effects.

With regard to the survival and response rates, the effect size for the relative risks (RRs) was determined by calculating the number of deaths for one year or the overall response. The overall response was defined as the complete response plus partial response, and was evaluated according to the standard World Health Organization (WHO) criteria (15).

Statistical analysis

QOL

Most reports did not show the estimates of the effect size for QOL measures. Therefore, a combined one-sided p-value (16,17) was calculated using one-sided p-values for each QOL scale that was obtained from the publications by the inverse normal method. One-sided p-values were calculated from the two-sided p-values that were obtained from the published studies under the hypothesis of a favorable outcome for carboplatin-based chemotherapy. If the estimate was positive, then p1i=p2i/2; if the estimate was negative, then p1i=1−p2i/2. When the p-value for the difference between regimens was not provided in the publication, it was calculated by the t-test using the difference in the scores of QOL scales for each regimen. The standard deviation (SD) was taken from ‘non-small cell lung cancer (all stages)’ in the EORTC QLQ-C30 Reference Values (18), or the report of the reliability and validity of FACT-L (14). In the instances where a study did not report the estimates and we were unable to obtain any information regarding the direction, we assumed all the combinations of the estimates (positive or negative), and calculated corresponding one-sided p-values for all the cases. For example, if there were two trials with missing directions of estimate, we calculated the p-values for four combinations of ‘positive/positive’, ‘positive/negative’, ‘negative/positive’ and ‘negative/negative’.

Survival and response rate

As for the sensitivity analysis using survival and response rate, overall estimates were examined using a random-effects model (DerSimonian-Laird method) (19) and a fixed-effects model (general variance-based method). A χ2 test was used to assess heterogeneity among trials. Considering that the fixed-effects model is useful only under conditions of homogeneity and that the power of statistical tests of heterogeneity is low, we planned to use the random-effects model as the primary method, irrespective of the test result for heterogeneity. A fixed-effects model was also used for sensitivity analysis. S-plus programs (16,20) were used for estimation of the random-effects and fixed-effects models. When the RRs for the survival and response rates were >1, each reflected a favorable outcome in the carboplatin arm.

In this study, a statistical test with a p-value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Study characteristics

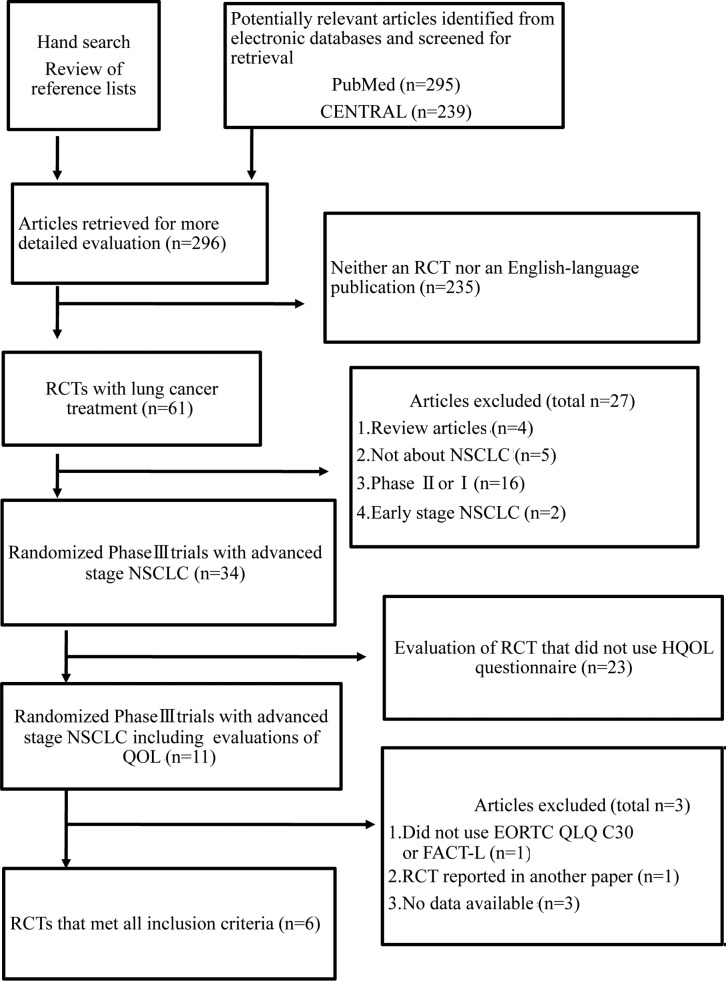

We identified six trials using the search strategy shown in Fig. 1 (21–26). The characteristics of the selected six trials are summarized in Table II. In total, 2,405 patients were randomized to receive cisplatin- (1,199 patients) or carboplatin-based chemotherapy (1,206 patients).

Figure 1.

Systematic review flow diagram. n, number of articles; CENTRAL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; RCT, randomized controlled trial; QOL, quality of life; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; EORTC, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Questionnaire; QLQ, quality of life questionnaire; FACT-L, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung; HQOL, health-related quality of life.

Table II.

Characteristics of selected trials.

| Authors/(Refs.) | Year | Treatment | Comparison arms

|

Patients (no.)

|

Aims of the trial | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDDP-based arm | CBDCA-based arm | CDDP-based arm | CBDCA-based arm | ||||

| Rosell et al (21) | 2002 | CDDP-PTX or CBDCA-PTX | Every 3 weeks CDDP-PTX |

Every 3 weeks CBDCA-PTX |

309 | 309 | Response rate (p); survival (s); toxicity (s); QOL (s) |

| Scagliotti et al (22) | 2002 | CDDP-GEM or CDDP-NVB or CBDCA-PTX | Every 4 weeks CDDP-NVB |

Every 3 weeks CBDCA-PTX |

203 | 204 | Response rate (p); survival (s);toxicity (s); QOL (s) |

| Danson et al (23) | 2003 | CDDP-MMC-IFO/CDDP-MMC-VBL or CBDCA-GEM | Every 3 weeks CDDP-MMC-IFO or CDDP-MMC-VBL |

Every 4 weeks CBDCA-GEM |

186 | 186 | Survival (p); TTP (s); QOL (s) response rate (s);toxicity (s); |

| Paccagnella et al (24) | 2004 | CDDP-MMC-VBL or CBDCA-MMC-VBL | Every 3 weeks CDDP-MMC-VBL |

Every 3 weeks CBDCA-MMC-VBL |

75 | 78 | QOL (p); toxicity (s); survival (s) |

| Rudd et al (25) | 2005 | CDDP-MMC-IFO or CBDCA-GEM | Every 3 weeks CDDP-MMC-IFO |

Every 3 weeks CBDCA-GEM |

210 | 212 | Survival (p); response rate (s); toxicity (s); QOL (s) |

| Booton et al (26) | 2006 | CDDP-MMC-IFO/CDDP-MMC-VBL or CBDCA-DTX | Every 3 weeks CDDP-MMC-IFO or CDDP-MMC-VBL |

Every 3 weeks CBDCA-DTX |

216 | 217 | Survival (p); response rate (s); QOL (s); toxicity (s); |

CDDP, cisplatin; CBDCA, carboplatin; NVB, vinorelbine; PTX, paclitaxel; MMC, mitomycin; IFO, ifosfamide; GEM, gemcitabine; DTX, docetaxel; VBL, vinblastine; p, primary end point; s, secondary end point; QOL, quality of life; TTP, time to progression.

QOL

For QOL, data that were assessed for the EORTC QLQ-C30 were used. Estimates of the effect size could not be obtained for any of the selected six trials. For the global QOL and seven symptom scales (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss and constipation), the one-sided p-value was calculated using a two-sided p-value. When the trial by Rudd et al (25), which was among the six selected trials, reported that the median value equaled 0, we were unable to decide whether the direction was negative or positive using the median, and the direction was decided according to the interquartile range from their report. Values of QOL scales in the six selected trials are summarized in Table III.

Table III.

Summary of quality of life (QOL) scalesa in selected trials (12–17 weeks).

| Authors/(Refs.) | Data | Treatment | Patients (no.) | Global QOL | Fatigue | Nausea and vomiting | Pain | Dyspnoea | Insomnia | Appetite loss | Constipation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosell et al (21) | p-value | CDDP | 171 | 0.939 | 0.955 | 0.149 | 0.058 | 0.163 | 0.985 | 0.084 | 0.468 |

| CBDCA | 172 | ||||||||||

| Scagliotti et al (22) | Mean change from baselineb | CDDP | 132 | - | 5 | 11 | - | - | - | −1 | - |

| CBDCA | 99 | - | 10 | 4 | 2 | - | |||||

| Danson et al (23) | Percentage change from baselineb | CDDP | 50 | 50%d | 70%d | 48%d | 36%c | 40%c | 20%d | 19%d | 21%d |

| CBDCA | 54 | 40%d | 49%d | 28%d | 46%c | 25%c | 35%d | 39%d | 2%d | ||

| Paccagnella et al (24) | p-value | CDDP | 39 | 0.40 | 0.15 | <0.001 | 0.47 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| CBDCA | 38 | ||||||||||

| Rudd et al (25) | Median change from baseline (interquartile range) | CDDP | 120 | 0 | 0.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (−1.0–0.50) | (−0.33–0.67) | (0–0.50) | (−0.50–0)) | (0–0) | (−1.0–0) | (−1.0–0) | (0–0) | ||||

| CBDCA | 112 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| (−1.0–1.0) | (−0.33–0.67) | (0–0) | (−0.50–0) | (−1.0–0) | (−1.0–1.0) | (−1.0–0) | (0–0) | ||||

| Booton et al (26) | Median change from baseline (interquartile range) | CDDP | 22 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −33 | 0 | 0 |

| CBDCA | 26 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

QOL scales, a higher score indicates a better global QOL and a greater severity of symptoms (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation);

value that was shown on a chart;

improvement;

deterioration. CDDP, cisplatin; CBDCA, carboplatin.

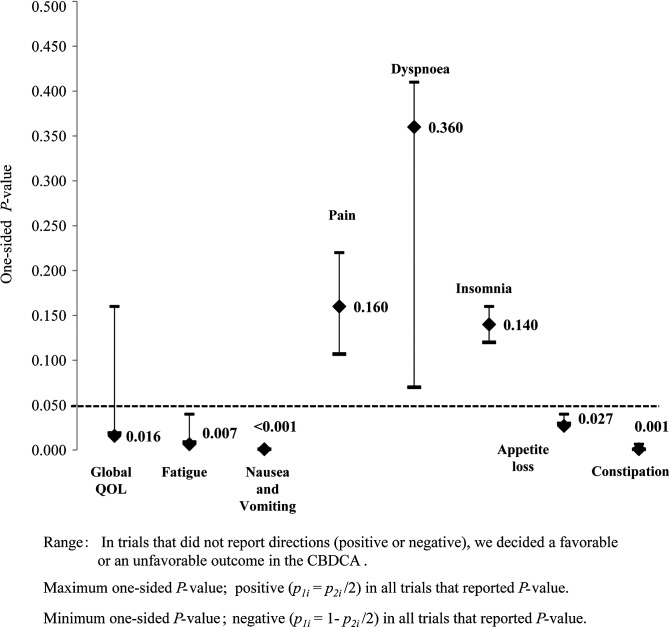

Using the inverse normal method, patients who received carboplatin-based chemotherapy had a higher global QOL (p=0.016) and less severe fatigue (p=0.007), nausea and vomiting (p<0.001), appetite loss (p=0.027) and constipation (p=0.001) than those who received cisplatin-based chemotherapy by the one-sided test (Table IV). For the global QOL, fatigue and constipation, the one-sided p-value was determined by calculations using data that were obtained from three of the selected trials, and for appetite loss, nausea and vomiting it was determined by calculations using data that were obtained from five of the selected trials.

Table IV.

Summary of quality of life (QOL) scales – one-sided p-value (12–17 weeks).

| Authors/(Refs.) | Test | Treatment | Global QOL | Fatigue | Nausea and vomiting | Pain | Dyspnoea | Insomnia | Appetite loss | Constipation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combining p-value of inverse normal methodd | 0.016 | 0.007 | <0.001 | 0.160 | 0.360 | 0.140 | 0.027 | 0.001 | ||

| Rosell et al (21) | Wei Johnson test of stochastic ordering | CDDP | (0.939) | (0.955) | (0.149) | 0.971 | (0.163) | (0.985) | (0.468) | |

| CBDCA | 0.042a | |||||||||

| Scagliotti (22) | One-way ANOVAb | CDDP | - | 0.910 | - | - | - | 0.750 | - | |

| CBDCA | 0.003a | |||||||||

| Danson et al (23) | -b | CDDP | 0.992 | 0.990 | 0.998 | |||||

| CBDCA | 0.015a | 0.001a | <0.001a | 0.045a | 0.001a | |||||

| Paccagnella et al (24) | Repeated measure ANOVA | CDDP | (0.400) | (0.150) | (0.470) | (0.170) | ||||

| CBDCA | <0.001a | 0.015a | 0.005a | 0.005a | ||||||

| Rudd et al (25) | Mann-Whitney U testc | CDDP | (0.720) | 0.840 | (0.750) | (0.250) | ||||

| CBDCA | 0.060a | 0.095a | 0.020a | 0.290a | ||||||

| Booton et al (26) | Mann-Whitney U testb | CDDP | (0.999) | (0.999) | 0.995 | |||||

| CBDCA | 0.500a | 0.009a | 0.500a | 0.500a | 0.500a |

CDDP, cisplatin; CBDCA, carboplatin; p-value, two-sided p-value. One-sided p-value could not be calculated since the direction (positive or negative) was not reported.

One-sided p-value, in favour of CBDCA.

Two-sided p-value was calculated by t-test using scores of QOL scale since the p-value of the difference from the regimens was not provided in the literature [Booton (26): two-sided p-value in nausea and vomiting was provided in the literature].

We decided whether the result was negative or positive using the median and interquartile ranges that were reported in the trial.

p<0.05 reflects a favorable outcome in CBDCA arm. Numbers in bold indicate the scale of a favorable outcome in CBDCA arm.

In the case of the five selected trials, with the study by Rudd et al (25) not being considered, global QOL was not significantly different between cisplatin- and carboplatin-based chemotherapy (p=0.063). Anticipated directions varied with positive or negative estimates in the QOL scales, and the ranges of one-side p-values are summarized in Fig. 2. For the Global QOL, the range of the one-sided p-value was determined by calculations using data that were obtained from five of the selected trials; the range of p-values varied from 0.019 to 0.160.

Figure 2.

Combining p-values of inverse normal method. Values represent combined p-values. CBDCA, carboplatin; QOL, quality of life.

One-year survival and response rate

For the one-year survival reported in all six trials, analyses showed no evidence of heterogeneity among studies (p=0.098). The RR was estimated as 1.058 (95% CI 0.914–1.224) by the random-effects model, and one-year survival (p= 0.451) did not differ significantly between cisplatin- and carboplatin-based chemotherapy.

Analysis of the response rate in the six trials revealed no evidence of heterogeneity among studies (p=0.892). The RR was estimated to be 0.970 (95% CI 0.866–1.087) by the random-effects model, and the response rates (p=0.603) were not significantly different in the comparison of cisplatin- to carboplatin-based chemotherapy.

Discussion

Patients who received first-line carboplatin-based chemotherapy had a higher global QOL and fewer symptoms of fatigue, nausea and vomiting, appetite loss and constipation than those who received cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Our results, which showed fewer symptoms of nausea and vomiting with carboplatin-based chemotherapy, agreed with the results of previous studies (10–12). Differences in the response rates and one-year survival were not significant when cisplatin- and carboplatin-based chemotherapy were compared. However, previous meta-analyses of RCTs comparing carboplatin- to cisplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC (10–12) showed a higher response rate with cisplatin-based chemotherapy, although the survival advantage was not significant with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Thus, in comparison of the two chemotherapeutic strategies, survival, which was the primary outcome measure in the clinical trials, did not vary significantly between treatments, although there were significant differences in QOL that favored carboplatin-based chemotherapy.

Previous reports of the choice between cisplatin or carboplatin have addressed points of controversy and, consequently, possible equivalency in efficacy, superior toxicity profiles and convenience of administration have led to the predominant role of carboplatin in the marketplace for the treatment of advanced NSCLC (27). The toxicity profile should help to guide decisions in choosing regimens (9,28). While QOL questionnaires, such as the EORTC QLQ-C30, may assess not only lung cancer symptoms, including toxicity profiles in addition to global QOL, clinical parameters had significant effects on QOL in patients undergoing chemotherapy (29). Thus, useful information for selecting suitable chemotherapeutic regimens may be obtained by QOL assessment. We found a significant difference in the Global QOL between the two regimens. We consider that it is important to evaluate QOL in addition to survival, response rate and toxicity in patients with advanced NSCLC. Various aspects of QOL may help physicians to deal with incurable patients with lung cancer in order to provide the most appropriate weight to potentially differing perceptions of QOL (30). Future studies should include QOL as a treatment outcome for first-line treatment.

The main use of QOL assessments in clinical trials has been to provide an additional outcome measure when comparing various oncological treatment regimens (31). For example, in a report of the effects on, or comparison of, survival and QOL in advanced NSCLC patients with regard to various treatments, Cullen et al stated that the effect of mitomycin, ifosfamide and cisplatin (MIC) on survival, observed in each trial separately, was reinforced by the consistently significant treatment effect, which was not achieved at the expense of short-term QOL (32). Bonomi et al reported that paclitaxel combined with cisplatin produced a modest survival improvement compared to etoposide plus cisplatin, without producing negative effects on QOL (33). In the present study, the survival rate was not significantly different when comparing cisplatin-to carboplatin-based chemotherapy. However, the patients who received carboplatin-based chemotherapy did have a higher QOL. QOL information is invaluable in understanding the full impact of the treatment differences on patient outcomes (34).

However, there were certain limitations to this study. Firstly, this meta-analysis includes only a small number of subjects in comparison to a previous study (12) (2,405 vs. 6,906 patients) since some of the trials failed to report any QOL measures. QOL is increasingly recognized as a major end-point in medical care (35), and QOL in lung cancer is an important treatment outcome in addition to length of survival (36). Nevertheless, there have been a few previous studies reporting QOL outcomes following such palliative treatment. This may lead to the collection of conservative p-values. However, our results suggest a significant association with certain QOL measures. We believe that we may be able to conduct statistically suitable analyses of the limited information we have available. Secondly, the literature published in 2002 was the earliest trial to provide QOL data, while in the previous study (12), the earliest literature was published in 1990. However, considering that the results for survival and response rates were not significantly different from our study, variations in the year of publication may not elicit significant bias.

In conclusion, the numbers of trials of treatment of advanced NSCLC have increased, particularly when the main objective is to avoid disease progression. If QOL assessments are performed and QOL is included as a treatment outcome, the patients receiving the palliative chemotherapy will receive useful information regarding the selection of a suitable chemotherapy regimen, taking into consideration QOL.

Acknowledgments

This report is based on special research in the National Institute of Public Health Biostat Program. The authors acknowledge the Program for the opportunity to accomplish this report. This study was financially supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research Grant C in 2010 (Grant No. 20590668).

References

- 1.Parkin DM. Global cancer statistics in the year 2000. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:533–543. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novello S, Le Chevalier T. Chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. Part 1. Early-stage disease. Oncology. 2003;17:357–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Petris L, Crinò L, Scagliotti GV, et al. Treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:ii36–ii41. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gridelli C, Perrone F, Nelli F, et al. Quality of life in lung cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:S21–S25. doi: 10.1093/annonc/12.suppl_3.s21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2996–3018. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.8.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Persson C, Ostlund U, Wennman-Larsen A, Wengström Y, Gustavsson P. Health-related quality of life in significant others of patients dying from lung cancer. Palliat Med. 2008;22:239–247. doi: 10.1177/0269216307085339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albers G, Echteld MA, de Vet HC, et al. Evaluation of quality of life measures for use in palliative care: systematic review. Palliat Med. 2010;24:17–34. doi: 10.1177/0269216309346593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beitz J, Gnecco C, Justice R. Quality of life end points in cancer clinical trials: the U.S. Food and Drug Administration perspective. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1996;20:7–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harper P, Plunket T, Khayat D. Quality trials and quality of life in non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3007–3008. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hotta K, Matsuo K, Ueoka H, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing cisplatin to carboplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3852–3859. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ardizzoni A, Boni L, Tiseo M, et al. Cisplatin- versus carboplatin-based chemotherapy in frst-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:847–857. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang J, Liang X, Zhou X, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing carboplatin-based to cisplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007;57:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality of life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:364–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cella DF, Bonomi AE, Lloyd SR, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) quality of life instrument. Lung Cancer. 1995;12:199–220. doi: 10.1016/0169-5002(95)00450-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James K, Eisenhauer E, Christian M, et al. Measuring response in solid tumors: unidimensional versus bidimensional measurement. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;17:523–528. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.6.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tango T. Medical Statistical Science Series 4. Asakura bookstore; Tokyo: 2009. An introduction to meta-analysis; pp. 99–101. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitehead A. Meta-analysis of Controlled Clinical Trials. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester: 2002. pp. 237–240. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott NW, Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, et al. EORTC QLQ-C30 Reference Values. Jul, 2008. [updated August 6, 2011]. http://groups.eortc.be/qol/downloads/reference_values_manual2008.pdf.

- 19.Petitti DB. Meta-analysis, Decision Analysis, and Cost-effectiveness Analysis. Oxford University Press; Oxford, New York: 2010. pp. 116–117. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spector P. An Introduction to S and S-Plus. Duxbury Press; Belmont, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosell R, Gatzemeier U, Betticher DC, et al. Phase III randomised trial comparing paclitaxel/carboplatin with paclitaxel/cisplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a cooperative multinational trial. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1539–1549. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scagliotti GV, De Marinis F, Rinaldi M, et al. Phase III randomized trial comparing three platinum-based doublets in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4285–4291. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danson S, Middleton MR, O'Byrne KJ, et al. Phase III trial of gemcitabine and carboplatin versus mitomycin, ifosfamide, and cisplatin or mitomycin, vinblastine, and cisplatin in patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;98:542–553. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paccagnella A, Favaretto A, Oniga F, et al. Cisplatin versus carboplatin in combination with mitomycin and vinblastine in advanced non small cell lung cancer. A multicenter, randomized phase III trial. Lung Cancer. 2004;43:83–91. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00280-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rudd RM, Gower NH, Spiro SG, et al. Gemcitabine plus carboplatin versus mitomycin, ifosfamide, and cisplatin in patients with stage IIIB or IV non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomized study of the London Lung Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:142–153. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Booton R, Lorigan P, Anderson H, et al. A phase III trial of docetaxel/carboplatin versus mitomycin C/ifosfamide/cisplatin (MIC) or mitomycin C/vinblastine/cisplatin (MVP) in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised multicentre trial of the British Thoracic Oncology Group (BTOG1) Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1111–1119. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hotta K, Matsuo K. Long-standing debate on cisplatin- versus carboplatin-based chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:96. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31802bb010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goffin J, Lacchetti C, Ellis PM, et al. First-line systemic chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:260–274. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c6f035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morita S, Kobayashi K, Eguchi K, et al. Influence of clinical parameters on quality of life during chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: application of a general linear model. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2003;33:470–476. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyg083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buccheri G, Vola F, Ferrigno D. Aspects of quality-of-life in patients with lung-cancer - a 3 observer evaluation study. Int J Oncol. 1993;2:537–544. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holzner B, Bode RK, Hahn EA, et al. Equating EORTC QLQ-C30 and FACT-G scores and its use in oncological research. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:3169–3177. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cullen MH, Billingham LJ, Woodroffe CM, et al. Mitomycin, ifosfamide, and cisplatin in unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer: effects on survival and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3188–3194. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonomi P, Kim K, Fairclough D, et al. Comparison of survival and quality of life in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with two dose levels of paclitaxel combined with cisplatin versus etoposide with cisplatin: results of an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:623–631. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hollen PJ, Gralla RJ. Comparison of instruments for measuring quality of life in patients with lung cancer. Semin Oncol. 1996;23:31–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Editorial Quality of life and clinical trials. Lancet. 1995;346:1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thatcher N, Hopwood P, Anderson H. Improving quality of life in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: research experience with gemcitabine. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:8–13. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]