Abstract

The aim of the present study was to investigate the osteogenic capability of rat calvarial periosteal cells in hypoxic conditions in vitro. Periosteum was obtained from the calvarial bone of Sprague-Dawley rats. Following primary tissue culture, subcultured cells were used in hypoxic or normal conditions. On days 1, 2, 3 and 4 following the cell culture, cell proliferation and mRNA and protein expression levels were evaluated. No significant difference in the cell proliferation rate was found between the normal and hypoxic condition groups. The hypoxic condition group exhibited a stronger expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)1α, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), Runx2, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), bone sialoprotein (BSP), osteocalcin (OCN) and periostin at the mRNA level compared to that of the normal condition group. The hypoxic condition group also exhibited a stronger expression of HIF1α, VEGF, bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)2, Runx2, ALP and BSP at the protein level compared to that of the normal condition group. In conclusion, periosteal cells cultured in hypoxic conditions demonstrated activated osteogenic capability in vitro.

Keywords: hypoxia, periosteum, osteogenic, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α, periostin

Introduction

Bone regeneration therapy is becoming common in regenerative medicine, and is used in the treatment of bone defects caused by periodontal disease and mandibular tumor resection. Bone marrow is often used as the typical vital material for bone regeneration; however, this requires an intricate procedure for harvesting. Recently, the periosteum has been cited as a bone supplement material that could be used as an alternative to bone marrow (1). There have also been reports that the periosteum has an osteogenic capability that is as high as bone marrow, which is often used for transplants in the maxillofacial area (2). A number of studies have been performed on the osteogenic capability of periosteal transplants (3,4). At present, collected periosteum is starting to be cultivated and clinically applied as a bone supplement (5–8).

However, it is not so easy to obtain the quantity of periosteum required for bone regeneration. To proliferate a sufficient quantity of cells for transplant, cell culture is known to be a good method. Furthermore, it is known that osteogenic capability is accelerated by changes in the environment, such as oxygen conditions. Miescher et al (10) as well as others (9,11) have reported that a hypoxic condition increased red blood cells and had various other effects on cells, such as the activation of glycolytic pathways and the induction of angiogenesis. Amemiya K et al (12) and Amemiya H et al (13) reported on the accelerated osteogenic capability of pulp cells and periodontal ligament cells in hypoxic conditions. However, no comparisons have been made to date regarding the osteogenic capability of periosteal cells in hypoxic and normal conditions. The purpose of this molecular biological study was to investigate the osteogenic capability of the cultured periosteal cells of rats when incubated under hypoxic conditions.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted in compliance with the Guidelines for the Treatment of Experimental Animals at the Tokyo Dental College (approval number 226102).

Animals and cell culture

Periosteal explants were harvested from the calvaria of 20 male Sprague-Dawley 7-week-old rats, each weighing approximately 250 g (Sankyo Labo Service, Tokyo, Japan). The skin incision was made and underlying muscular fibrous connective tissue was removed to expose the periosteum. The periosteum was stripped off mechanically using fine forceps. The obtained periosteum was mechanically cut into sections approximately 2×2 mm in size. The cut periosteum was placed with the osteogenic (cambium) side down onto the surface of 35-mm culture dishes for 30 min, then culture medium was added and the dishes were cultured for 4 days. For the culture, Medium 199 containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 50 μg/ml gentamicin, supplemented with 10−8 M dexametasone, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate and 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid was used (13).

To set the oxygen conditions, a BL-40 M CO2 incubator (JuujiField Labo; Bio Labo, Tokyo, Japan) which regulates the condition of oxygen in the air to nitro-oxygen was used. For the hypoxic condition group, cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere at conditions of 5% O2, 5% CO2 and 90% N2 at 37°C. For the normal condition group, cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere at normal conditions of 20% O2, 5% CO2 and 75% N2 at 37°C (15).

Cell proliferation assay

Subcultured cells from each group were harvested with 0.25% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA, and approximately 3×103 cells were seeded onto the 35-mm culture dishes. At 1, 2, 3 and 4 days after the culture, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and harvested using 0.25% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA. The number of cells was counted using a Vi-CELL™ Coulter counter (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA).

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Approximately 3×104 cells from each group were seeded in 35-mm dishes and cultured as detailed above. Total RNA was extracted from each sample using the acid guanidium thiocyanate/phenol-chloroform method as follows. The culture medium was removed and cells were rinsed twice using PBS. The cells were homogenized in 1 ml TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) after 1, 2, 3 and 4 days of incubation. Each solution was transferred to a 1.5 ml tube containing chloroform and mixed. The tubes were centrifuged at 13,200 rpm at 4°C for 20 min, after which the supernatants were placed in 1.5 ml tubes containing 250 μl 100% isopropanol (half the amount of the TRIzol reagent) at −80°C for 1 h. Following centrifugation at 13,200 rpm at 4°C for 20 min, the supernatants were discarded and the remaining total RNA pellets were washed with 70% cold ethanol. Total RNAs were dissolved in 50 μl RNase-free (diethylpyrocarbonate-treated) water and then reverse transcribed and amplified in 20 μl volumes using a reverse transcription kit (QuantiTect; Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) containing RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) buffer (2 U/μl RNase inhibitor, 0.25 U/μl reverse transcriptase, 0.125 μM oligo(dT) adaptor primer and 5 mM MgCl2 in RNase-free water) (13). RT-PCR products were analyzed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR using a TaqMan gene expression assay (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) for the target genes: Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)1α (Rn00577560_m1, 72 bp), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Rn00582935_m1, 75 bp), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (Rn01516028_m1, 68 bp), bone sialoprotein (BSP) (Rn01450118_m1, 89 bp), osteocalcin (OCN) (Rn01455285_g1, 81 bp), Runx2 (Rn01512296_m1, 116 bp). The TaqMan endogenous control (Applied Biosystems) for the target gene β-actin (Rn01768120_m1, 63 bp) was used as an endogenous control. All PCR reactions were performed using a real-time PCR 7500 fast system (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression quantification using TaqMan gene expression assays was performed as the second step in a two-step RT-PCR. Assays were performed in 20 μl single-plex reactions containing TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master mix, TaqMan gene expression assays, distilled water and complementary DNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reaction conditions consisted of 50 cycles at 95°C for 3 sec and at 62°C for 30 sec.

ALP activity

ALP activity was measured using a colormetric assay kit (Alkaline Phosphatase Opt; Roche Diagnostics Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Cultured cells (3500 cells per well) were washed with calcium- and magnesium-free PBS at each time-point, and harvested with demineralized and distilled water for 60 sec using a sonicator (Sonifier 250D; Branson, Rochester, MI, USA) on ice. Each homogenate was centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min and the supernatants were used for assay. One milliliter of premixed solution (1 M diethanolamine buffer, pH 9.8, with 0.5 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM p-nitrophenylphosphate, kept at 37°C) was added to 10 μl supernatant. Absorption at 405 nm for p-nitrophenol was measured using a spectrophotometer (Ultrospec 3000; Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnologies, Rochester, NY, USA). To determine the specific activity of ALP, protein concentrations in each lysate were determined using the Pierce bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). A volume of 100 μl of each cell lysate was added to 100 μl bicinchoninic acid working reagent (kept at 37°C for 30 min). Absorbance was measured at 595 nm using a microplate reader. ALP activity was calculated according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot analysis

The expression of HIF1α, bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)2, Runx2, BSP, OCN, VEGF, Glut1 and periostin in periosteal cells was assessed by western blot analysis. Blocking was performed by PVDF blocking reagent to confirm specific and non-specific bands. Periosteal cells were seeded in 60-mm cell culture dishes and were cultured for 4 days. After each culture period, the cells were washed with CMF-PBS, and resuspended in radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer for 60 sec using a sonicator (Branson) on ice. Each homogenate was further stirred using a tube rotator (As One) for 20 min and then centrifuged at 9,300 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The protein concentration of each supernatant was measured using the Nowak method (16). Samples (30 μg protein each) were electrophoresed in 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels and were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using standard methods (12). Primary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:1000. These antibodies comprised rabbit polyclonal antibodies against HIF1α, BMP2, Runx2, BSP, OCN, VEGF, Glut1 and periostin. As a secondary antibody, horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody was used. Specifically bound antibodies were detected on the film with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (ECL Western blot detecting system; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Images were analyzed using NIH Image (Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD, USA) and each density was normalized with actin from the same sample.

Statistical analysis

The results were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and then compared by Scheffe’s test.

Results

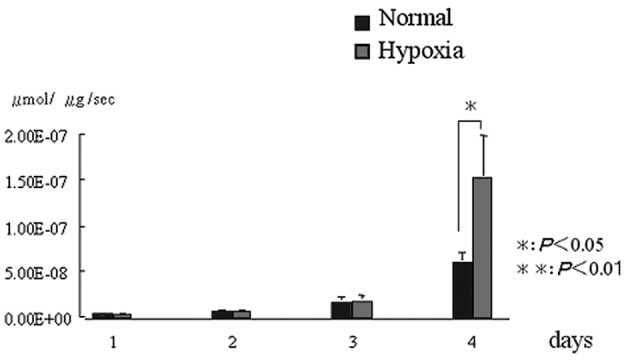

Cell proliferation rate

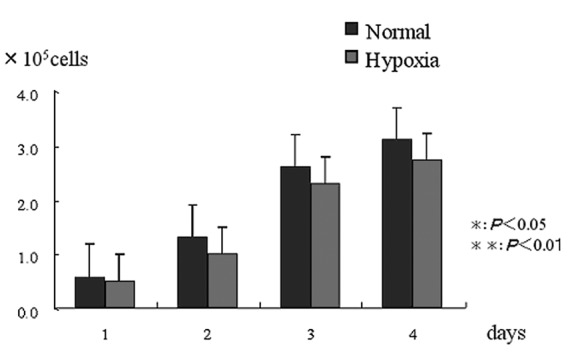

There was no significant difference in the cell proliferation rate between the normal and hypoxic condition groups (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Cell proliferation rate. No difference was noted between the hypoxic and normal condition groups at any of the time-periods.

mRNA expression (RT-PCR)

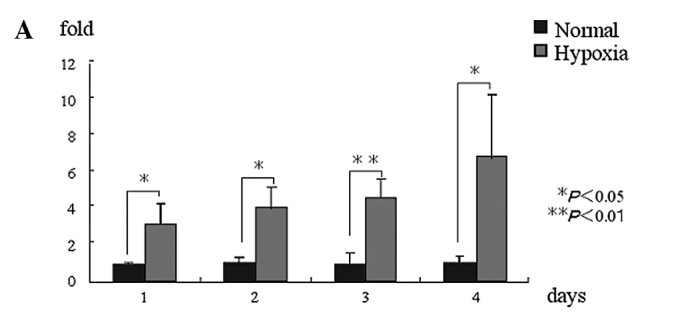

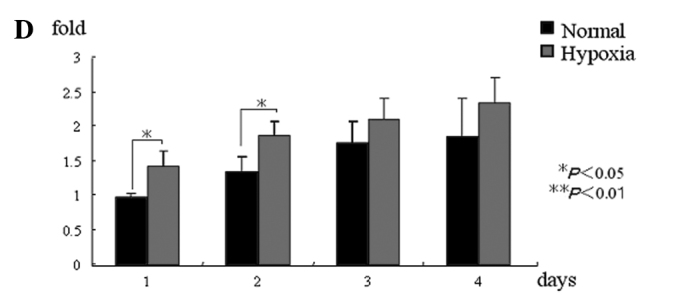

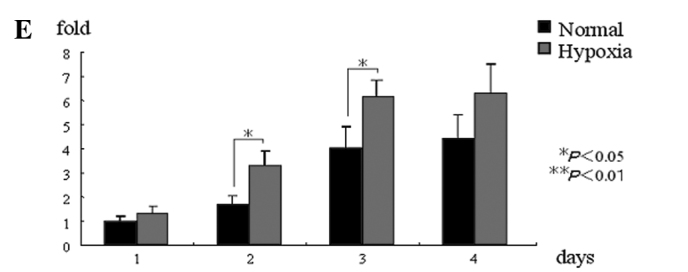

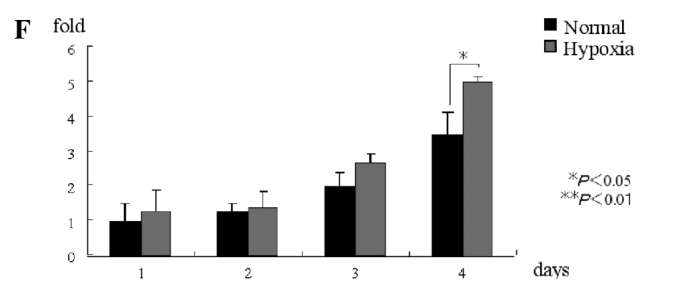

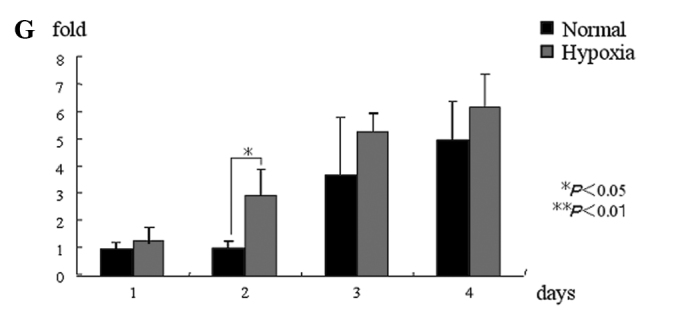

HIF1α expression was higher in the hypoxic condition group than in the normal condition group on days 1, 2, 3 and 4 (P<0.05). VEGF expression was significantly higher in the hypoxic condition group than in the normal condition group on days 3 and 4 (P<0.05). In particular, a significantly high value was indicated on day 3 (P<0.01). Runx2 expression was significantly higher in the hypoxic condition group than in the normal condition group on day 1 (P<0.05). ALP expression was significantly higher in the hypoxic condition group than in the normal condition group on days 1 and 2 (P<0.05). BSP expression was significantly higher in the hypoxic condition group than in the normal condition group on days 2 and 3 (P<0.05). OCN expression was significantly higher in the hypoxic condition group than in the normal condition group on day 4 (P<0.05). In particular, a significantly high value was indicated on day 3 (P<0.01). Periostin expression was significantly higher in the hypoxic condition group than in the normal condition group on day 2 (P<0.05) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

mRNA expression. (A) HIF1α mRNA expression in the hypoxic condition group was significantly higher than that in the normal condition group at all of the time-periods. (B) VEGF mRNA expression in the hypoxic condition group was significantly higher than that in the normal condition group on days 2 and 3, but was not significantly different at other time-periods. (C) Runx2 mRNA expression in the hypoxic condition group was significantly higher than that in the normal condition group on day 1, but was not significantly different at other time-periods. (D) ALP mRNA expression in the hypoxic condition group was significantly higher than that in the normal condition group on days 1 and 2, but was not significantly different at other time-periods. (E) BSP mRNA expression in the hypoxic condition group was significantly higher than that in the normal condition group on days 2 and 3, but was not significantly different at other time-periods. (F) OCN mRNA expression in the hypoxic condition group was significantly higher than that in the normal condition group on day 4, but was not significantly different at other time-periods. (G) Periostin mRNA expression in the hypoxic condition group was significantly higher than that in the normal condition group on day 2, but was not significantly different at other time-periods. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. HIF1α, hypoxia-inducible factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; BSP, bone sialoprotein; OCN, osteocalcin.

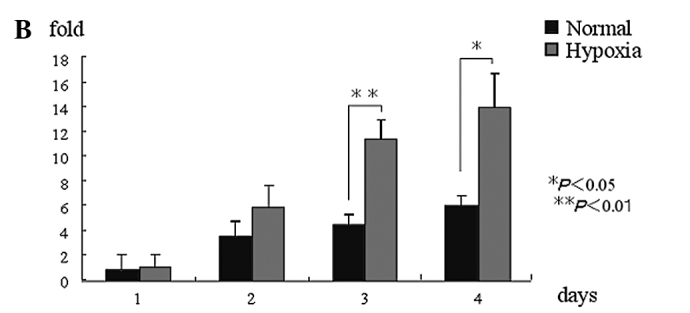

ALP activity

In comparison to the normal condition group, the hypoxic condition group demonstrated a higher (P<0.05) expression of ALP activity on day 4. However, there were no significant differences at the other time-periods (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity. Compared to the normal condition group, the hypoxic condition group demonstrated a higher expression of ALP activity on day 4. *P<0.05, **P<0.01

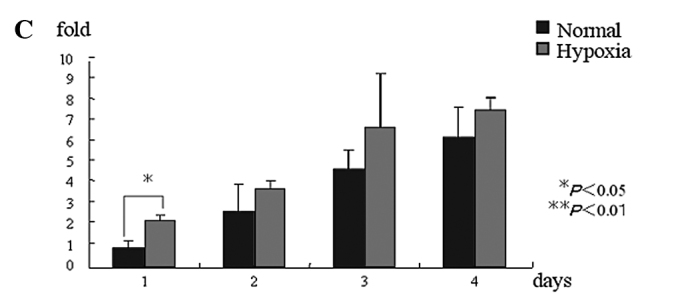

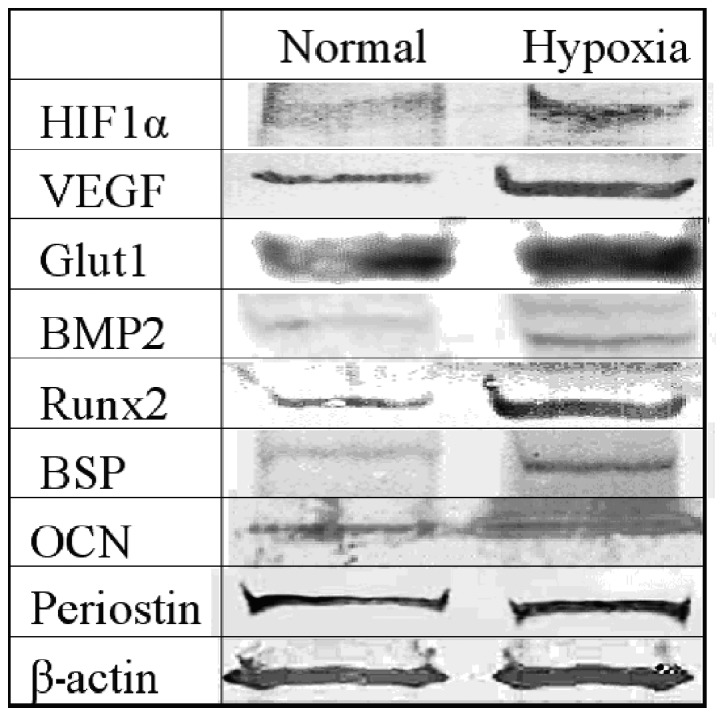

Protein expression

HIF1α, VEGF, BMP2, Runx2 and BSP were all expressed more strongly in the hypoxic condition cell group than in the normal condition group. Glut1, OCN and periostin were all expressed in both the normal and hypoxic condition groups (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Protein expression. We carried out an evaluation of the normal and the hypoxic condition group on day 4 after the incubation. HIF1α, VEGF, BMP2, Runx2 and BSP were all expressed more strongly in the hypoxic condition cell group than in the normal condition group. Glut1, OCN and periostin were all expressed in both the normal and hypoxic condition groups. HIF1α, hypoxia-inducible factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; BMP2, bone morphogenetic protein 2; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; BSP, bone sialoprotein; OCN, osteocalcin.

Discussion

It has been reported that osteogenic capability is just as remarkably high in periosteal cells as it is in bone marrow cells, which are the material typically used in bone regeneration therapy (8). Pittenger et al reported that SH2 and SH3 are mesenchymal stem cell markers that differentiate into osteoblasts within bone marrow (17). Since then, the same markers have also been reported in the periosteum (18,19). Furthermore, Sakaguchi et al reported that there was no significant difference between periosteal and bone marrow cells in terms of the expression of CD44, CD90 and CD105, which are also mesenchymal stem cell markers (20). We observed that rat cultured bone marrow cells expressed the same markers as cultured periosteal cells using exactly the same antibodies as were used in this study (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that both periosteal and bone marrow cells have similar characteristics, in terms of their quality and quantity of stem cells and strong osteogenic capability.

In the maxillofacial area, the mandible has been cited as a collection site for actual periosteal transplants. The calvarial periosteum used in this study also originates from intramembranous ossification as in the mandibular bone. Jeroen et al (22) conducted comparisons of the periosteal osteogenic capability of rabbits and humans, and Krzysztof et al (21) conducted comparisons in chickens, dogs, mice and rats. Furthermore, Wei et al compared periosteum of the same size collected from the diaphyseal and epiphyseal region of the femurs of rats according to age (23,24). In these studies, there were differences in the speed of differentiation and the degree of osteogenic capability according to species, site and age, but they were mostly in agreement regarding cell kinetics. Therefore, this molecular biological study of cell kinetics using calvarial periosteal cells of rats may assist in the clinical application of human mandible periosteal cells.

Generally, it is known that the cell proliferation ratio changes according to the type of hypoxic condition that the cells are placed in (25–30). Also, the hypoxic condition affects the cell kinetics even when the same cells are used in the condition. Yoshida et al studied mouse embryonic fibroblasts in vitro with the oxygen condition set to 1, 5 and 20%, and found the number of colonies to be highest at the condition of 5% oxygen (31). Senzui et al reported that the cell count in rat pulp cells decreased at an oxygen condition of 5% (16). No significant difference was noted in the hypoxic condition at 5% oxygen in this study. These results shows that there is a marked difference in cell proliferation between rat periosteal cells and mouse embryonic fibroblasts under hypoxic conditions.

HIF1α is a hypoxia-inducible factor, and expressed in hypoxic conditions. Hanada et al reported that the expression of BMP2 raised the osteogenic capability of the periosteum (32). In this study, a stronger protein expression of BMP2 was noted in the hypoxic condition group than in the normal condition group. HIF1α induces hypoxia via integrin-linked kinase (ILK), Akt and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), causing BMP2 to be strongly expressed (33) and accelerating the cell differentiation.

In this study, the hypoxic condition group exhibited significantly and chronologically higher values than the normal condition group which may suggest that periosteal cells are resistant to hypoxia. In this study, Glut1 and VEGF have been cited as being strongly expressed at either the protein or mRNA level in hypoxic conditions. Glut1, which comprises 5% of red blood cell membrane protein, activates the glycolytic pathways, and VEGF activates angiogenesis and HIF1α is closely related to osteogenic capability (34–38). HIF1α binds to hypoxia response elements located in the gene promoters to regulate the transcription of VEGF and Glut1 (39). Runx2 is an initial transcription factor for the differentiation process of osteoblasts. Komori et al (40) and Otto et al (41) proved that Runx2 gene is vital to the differentiation and osteogenesis of osteoblasts since in Runx2 knockout mice, osteoblast differentiation is clearly suppressed and osteoblast formation does not take place. Kobayashi et al proved that although neither endochondral ossification nor intramembranous ossification occur in Runx2 knockout mice, since the differentiation of damaged mesenchymal cells into adipocytes and chondrocytes is possible, it is an essential factor in the initial stage of osteoblast differentiation (42). Liu et al reported that although Runx2 functions as an accelerator in the initial stage of osteoblast differentiation, it inhibits mature osteoblasts and osteocytes (43). In this study, both mRNA and protein levels of Runx2 were strongly expressed in the hypoxic incubation group. This suggests that periosteal cells, which might include pre-osteoblast stage cells, react to the hypoxic condition. ALP is known to be a marker for early osteogenesis, BSP is known to be a marker for pre-calcification, and OCN is known to be a marker for post-calcification (44). In this study, both these markers showed higher expression at both the protein and mRNA level in the hypoxic condition group. In particular, BSP was more strongly expressed on days 2 and 3 and OCN was more strongly expressed on day 4 in the hypoxic condition group. It would appear that a hypoxic condition is also effective for osteoblasts to mature to osteocytes.

Periostin, which is known to be a specifically expressed protein of the osteoblastic cells of the periodontal ligament and periosteum, was strongly expressed at the mRNA level in the hypoxic condition group in this study. Hiouchi et al reported that periostin existed only in the periosteum, and was expressed in the periodontal ligament induced by some kind of mechanical stress (45). Kudo et al (47) as well as others (46,48) reported that periostin affects the ligands α-V/β3 and α-V/ β5, and is involved in the angiogenesis of malignant tumors. Another report suggests that periostin is involved in the phosphorylation of FAK and Akt in αv-integrin pathways during the recovery process following a myocardial infarction (49). The fact that Akt is a factor in the upregulation of HIF1α (50) suggests that there must be a significant correlation between periostin and hypoxic conditions.

In conclusion, hypoxic conditions activate the osteogenic capability of periosteal cells in rats.

References

- 1.Zheng Y, Ringe J, Liang Z, et al. Osteogenic potential of human periosteum-derived progenitor cells in PLGA scaffold using allogeneic serum. J Zhejiang Univ. 2006;7:817–824. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2006.B0817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayashi O, Katsube Y, Hirose M, et al. Comparison of osteogenic ability of rat mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, periosteum, and adipose tissue. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008;82:238–247. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9112-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallie WE, Robertson DE. The periosteum. Can Med Assoc J. 1914;4:33–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okuda K, Tanabe H, Suzuki K, et al. Platelet-rich plasma combined with a porous hydroxyapatite graft for the treatment of intrabony periodontal defects in humans:a comparative controlled clinical study. J Periodontal Res. 2005;76:890–898. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.6.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamamiya K, Okuda K, Kawase T, et al. Tissue-engineered cultured periosteum sheets combined with platelet-rich plasma and porous hydroxyapatite graft in treating human osseous defects. J Periodontol. 2008;79:811–818. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawase T, Okuda K, Kogami H, et al. Human periosteum-derived cells combined with superporous hydroxyapatite blocks used as an osteogenic bone substitute for periodontal regenerative therapy: an animal implantation study using nude mice. J Periodontol. 2010;81:420–427. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mase J, Mizuno H, Okada K, et al. Cryopreservation of cultured periosteum: Effect of different cryoprotectants and pre-incubation protocols on cell viability and osteogenic potential. Cryobiology. 2006;52:182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okuda K, Yamamiya K, Kawase T, et al. Treatment of human infrabony periodontal defects by grafting human cultured periosteum sheets combined with platelet-rich plasma and porous hydroxyapatite granules: Case series. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2009;11:206–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas ED. In vitro studies of erythropoiesis. II. The effect of anoxia on heme synthesis. Blood. 1955;10:612–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miescher F. Uber die beziehungen zwischen meereschohe und beschaffenheit des blutes. Cor-Bl f Schweiz Aerzte. 1893;23:809. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wan C, Shao J, Shawn RG, et al. Role of HIF-1α in skeletal development. Ann New York Acid Sci. 2010;1192:322–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05238.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amemiya K, Kaneko Y, Inoue T, et al. Pulp cell responses during hypoxia and reoxygenation in vitro. Eur J Oral Sci. 2003;111:32–38. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2003.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amemiya H, Matsuzaka K, Inoue T, et al. Cellular responses of rat periodontal ligament cells under hypoxia and re-oxygenation conditions in vitro. J Periodontal Res. 2008;43:322–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2007.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Somiya H, Matsuzaka K, Inoue T, et al. Molecular and morphological analyse of the osteogenic activity of rat cultured periosteum cells in vivo and in vitro. Oral Med Pathol. 2009;14:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senzui S, Matsuzaka K, Inoue T, et al. Responses of immature dental pulp cells to hypoxic stimulation. Oral Med Pathol. 2010;14:107–111. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nowak TS. Synthesis of a stress protein following transient ischemia in the gerbil. J Neurochem. 1985;45:1635–1641. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb07236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pittenger MF, Alastair M, Marshak R. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ringe J, Leinhase I, Stich S, et al. Human mastoid periosteum-derived stem cells: promising candidates for skeletal tissue engineering. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2008;2:136–146. doi: 10.1002/term.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierre C. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: historical overview and concepts. Hum Gene Ther. 2010;21:1045–1056. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakaguchi Y, Sekiya I, Muneta T, et al. Comparison of human stem cells derived from various mesenchymal tissues. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2521–2529. doi: 10.1002/art.21212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krzysztof H, Wlodarski M. Normal and heterotopic periosteum. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;241:265–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeroen E, Frank PL. Species specificity of ectopic bone formation using periosteum-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2203–2213. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei F, Crawford R, Xiao Y. Structural and cellular differences between metaphyseal and disphyseal periosteum in different aged rats. Bone. 2008;42:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei F, Stefan R, Xiao Y, et al. Structural and cellular features in metaphyseal and disphyseal periosteum of osteoporotic rats. J Mol Histol. 2010;10:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beau J, Robert S, Peter C, et al. Hypoxia-amplified proliferation of human dental pulp cells. J Dent Res. 2009;25:818–823. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ueno Y, Kitamura C, Nishihara T, et al. Re-oxygenation improves hypoxia-induced pulp cell arrest. J Dent Res. 2006;85:824–828. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaneko S, Takamatsu K, Shinozaki N, et al. Individual tissue culture system in a disposable capsule with hypoxic atmosphere. Ann Cancer Res Therap. 2008;16:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jan D, Dennis L, Oosterwyck HV. Towards a quantitative understanding of oxygen tension and cell density evolution in fibrin hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2010;93:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiawei H, Damian C, Kent JL, et al. Oxygen tension differentially influences osteogenic differentiation of human adipose stem cells in 2D and 3D cultures. J Cell Biochem. 2010;110:87–96. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirao M, Hashimoto J, Yoshikawa H. Oxygen tension is an important mediator of the transformation of osteoblasts to osteocytes. J Bone Miner Metab. 2007;25:266–276. doi: 10.1007/s00774-007-0765-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida Y, Takahashi K, Yamanaka S, et al. Hypoxia enhances the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;8:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanada K, Solchaga LA, Brian J. BMP-2 induction and TGF-β1 modulation of rat periosteum cell chondrogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2001;81:284–294. doi: 10.1002/1097-4644(20010501)81:2<284::aid-jcb1043>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pieter J, Frank E, Voncken RK, et al. A novel in vivo model to study endochondral bone formation; HIF-1α activation and BMP expression. Bone. 2007;40:409–418. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imai M, Ishibashi H, Shirasuna K, et al. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor in oral cancer cells by HIF-1 decoy. J Jpn Stomatol. 2005;54:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chao W, Gillbert SR, Clemens L, et al. Activation of the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α pathway accelerates bone regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;15:686–691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708474105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akiyama M, Nakamura M. Bone regeneration and neovascularization processes in a pellet culture system for periosteal cells. Cell Transplant. 2009;18:443–452. doi: 10.3727/096368909788809820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryan C, Riddle RK, Thomas L, et al. Role of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in angiogenic-osteogenic coupling. J Mol Med. 2009;87:583–590. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0477-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagano M, Kimura K, Ohneda O, et al. Hypoxia responsive mesenchymal stem cells derived from human umbilical cord blood are effective for bone repair. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:1195–1209. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hwang J, Weng J, Kuo W, et al. Hypoxia-induced compensatory effects as related to shh and HIF1α in ischemia embryo rat heart. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;311:1215–1220. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9708-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, et al. Target disruption of Cbfa1 result in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturation arrest of osteoblasts. Cell. 1997;89:755–764. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Otto F, Thornell AP, Crompton T, et al. Cbfa1, a candidate gene for cleidocranial dysplasia syndrome, is essential for osteoblast differentiation and bone development. Cell. 1997;89:765–771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kobayashi H, Gao Y, Komori K. Multilineage differentiation of Cbfa1 deficient calvial cells in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273:630–636. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu W, Toyosawa S, Furuichi T, et al. Overexpression of Cbfa1 in osteoblasts inhibits osteoblast maturation and causes osteopenia with multiple fractures. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:87–100. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Q, Huang C, Zhang X, et al. Expression of endogenous BMP-2 in periosteal progenitor cells is essential for bone healing. Bone. 2010;10:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.10.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horiuchi K, Amizuka N, Kudo A, et al. Idenitification and characterization of a novel protein, periostin, with restricted expression to periosteum and periodontal ligament and increased expression by transforming growth factor β. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1239–1249. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.7.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gillan L, Matei D, Chang B, et al. Periostin secreted by epithelial ovarian carcinoma is a ligand for alpha-V/beta3 and alpha-V/beta5 integrins and promotes cell motility. Canc Res. 2002;62:5358–5364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kudo Y, Ogawa I, Takata T, et al. Periostin promotes invasion and anchorage-independent growth in the metastatic prosess of head and neck cancer. Canc Res. 2006;14:6928–6935. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shao R, Bao S, Dang T, et al. Acquired expression of periostin by human breast cancers promotes tumor angiogenesis through up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3992–4003. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.9.3992-4003.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shimazaki M, Nakamura K, Kudo A, et al. Periostin is essential for cardiac healing after acute myocardial infarction. J Exp Med. 2008;205:295–303. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tseng W, Yang S, Tang C, et al. Hypoxia induces BMP-2 expression via ILK, Akt, mTOR, and HIF-1 pathways in osteoblasts. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223:810–818. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]