Background: Vaccinia virus transcription occurs in pre- and post-DNA replicative stages.

Results: We mapped authentic RNA start sites preceding 90 annotated postreplicative reading frames and at many more sites within coding and non-coding regions.

Conclusion: Postreplicative promoter sequences are distributed throughout the genome, resulting in enormous transcriptional complexity.

Significance: The large number of previously unmapped transcripts may have novel functions.

Keywords: Animal Viruses, DNA Viruses, mRNA, Pox Viruses, RNA Synthesis, Transcription, Transcriptomics

Abstract

Poxviruses are large DNA viruses that replicate within the cytoplasm and encode a complete transcription system, including a multisubunit RNA polymerase, stage-specific transcription factors, capping and methylating enzymes, and a poly(A) polymerase. Expression of the more than 200 open reading frames by vaccinia virus, the prototype poxvirus, is temporally regulated: early mRNAs are synthesized immediately after infection, whereas intermediate and late mRNAs are synthesized following genome replication. The postreplicative transcripts are heterogeneous in length and overlap the entire genome, which pose obstacles for high resolution mapping. We used tag-based methods in conjunction with high throughput cDNA sequencing to determine the precise 5′-capped and 3′-polyadenylated ends of postreplicative RNAs. Polymerase slippage during initiation of intermediate and late RNA synthesis results in a 5′-poly(A) leader that allowed the unambiguous identification of true transcription start sites. Ninety RNA start sites were located just upstream of intermediate and late open reading frames, but many more appeared anomalous, occurring within coding and non-coding regions, indicating pervasive transcription initiation. We confirmed the presence of functional promoter sequences upstream of representative anomalous start sites and demonstrated that alternative start sites within open reading frames could generate truncated isoforms of proteins. In an analogous manner, poly(A) sequences allowed accurate mapping of the numerous 3′-ends of postreplicative RNAs, which were preceded by a pyrimidine-rich sequence in the DNA coding strand. The distribution of postreplicative promoter sequences throughout the genome provides enormous transcriptional complexity, and the large number of previously unmapped RNAs may have novel functions.

Introduction

High throughput DNA sequencing has revealed unexpected transcriptional complexity in eukaryotes (1–4) and cells infected with large viruses (5–7). The poxviruses comprise a family of enveloped DNA viruses that replicate exclusively in the cytoplasm of infected cells (8). The latter capability is dependent on the encoding by poxviruses of highly conserved enzymes and factors for expression and replication of their large genomes. A thorough understanding of poxvirus transcription will provide insights into their complex biology and may improve the design of vaccines and therapeutics based on poxvirus expression vectors.

The transcriptional program of vaccinia virus (VACV),2 the prototype poxvirus, is divided into early, intermediate, and late stages that are regulated in a cascade fashion by sequential synthesis of specific transcription factors, which operate in conjunction with a viral multisubunit eukaryotic-like DNA-dependent RNA polymerase (8). The early transcription system, including RNA polymerase, transcription factors, capping enzyme, and poly(A) polymerase, is packaged within infectious virus particles, enabling synthesis of translatable mRNAs almost immediately after entry of the virus core into the cytoplasm. The de novo synthesized products of the early genes include the enzymes and factors needed for transcription of the intermediate genes on newly replicated viral DNA templates. The products of the intermediate genes include factors that enable transcription of late genes, the products of which include the early transcription factors that are packaged in assembling virions for use in the next round of infection. Because the expression of intermediate and late genes is dependent on viral DNA replication, they are referred to as postreplicative (PR) genes. Recent experiments suggest that there are 118 early and 93 PR genes with the latter divided into 53 intermediate, 38 late, and two for which expression was not detectable by Western blotting (5, 9). Early, intermediate, and late stage promoters have distinctive sequences, although some have dual specificities (9–14). A common, essential feature of intermediate and late promoters is three or more consecutive A residues in the coding strand that constitute the RNA start site. Frequently, the third A overlaps the ATG of the translation initiation codon. During transcription initiation, the RNA polymerase slips, resulting in a novel 5′-poly(A) leader (15–19). In addition, all classes of VACV mRNAs have 5′-caps and 3′-poly(A) tails synthesized by viral enzymes, but RNA splicing does not occur.

Although poxvirus genomes are much smaller than those of their hosts, they nevertheless pose daunting challenges for transcriptome analysis by conventional methods. The close spacing of open reading frames (ORFs) maximizes coding capacity but makes it difficult to map individual transcripts. This is compounded by the extensive overlapping of transcripts, especially at the PR stage, which is evidenced by length heterogeneity of RNAs (20, 21), occurrence of complementary double-stranded RNAs (22, 23), and RNA coverage of virtually every nucleotide of the VACV genome (5, 9). The heterogeneous RNA length has been attributed mainly to imprecise termination of PR mRNAs and to a lesser extent to 3′-poly(A) tails and 5′-poly(A) leaders. Another factor contributing to RNA heterogeneity suggested by our previous analysis of VACV early transcripts (14) is pervasive transcription initiation. To evaluate these possibilities, it is necessary to analyze RNA 5′- and 3′-ends with high precision and to distinguish 5′-ends derived by processing from those representing true transcription start sites (TSSs).

For the present study, we adapted tag-based RNA sequencing methods (14, 24, 25) to analyze the 5′- and 3′-ends of VACV postreplicative mRNAs. Importantly, the poly(A) leaders allowed us to distinguish true TSSs from 5′-ends produced by cleavage and demonstrate pervasive initiation of VACV postreplicative RNAs. In addition, the polyadenylated 3′-ends were extremely heterogeneous. These data provide new insights into poxvirus transcription, imply the existence of previously unrecognized gene products, and suggest a strategy for expressing new genes from endogenous or horizontally acquired DNA sequences.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells and Viruses

HeLa S3 cells were cultured in minimum essential medium with spinner modification (Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD) and 5% equine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The Western Reserve (WR) strain of VACV (American Type Culture Collection VR-1354) was used. The preparation, sucrose gradient purification, and titration of virus have been described previously (26, 27). HeLa S3 cells (107/ml) were infected with 20 plaque-forming units/cell VACV for 30 min and then diluted to 5 × 105 cells/ml with spinner medium containing 5% serum. The cells were harvested for RNA preparation at 4 and 8 h postinfection.

Recombinant virus v147-3×FLAG contains three copies of the FLAG epitope (DYKDHDGDYKDHDIDYKDDDDK) at the C terminus of VACWR147 ORF. The virus was generated by homologous recombination in cells infected with VACVWR, transfected with DNA, and purified by three rounds of plaque isolation as described previously (27). Recombinant DNA for v147-3×FLAG was assembled by overlapping PCR of (i) ∼500 bp of DNA upstream of the stop codon of VACWR147 ORF, (ii) DNA encoding 3×FLAG followed by a stop codon, (iii) the enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) ORF under control of the VACV late p11 promoter, and (iv) ∼500 bp of DNA downstream of VACWR147 ORF.

RNA Isolation and cDNA Deep Sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from VACV-infected cells using Trizol according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Polyadenylated mRNA was isolated with a Dynabeads mRNA DIRECT kit (Invitrogen) and treated with DNase I.

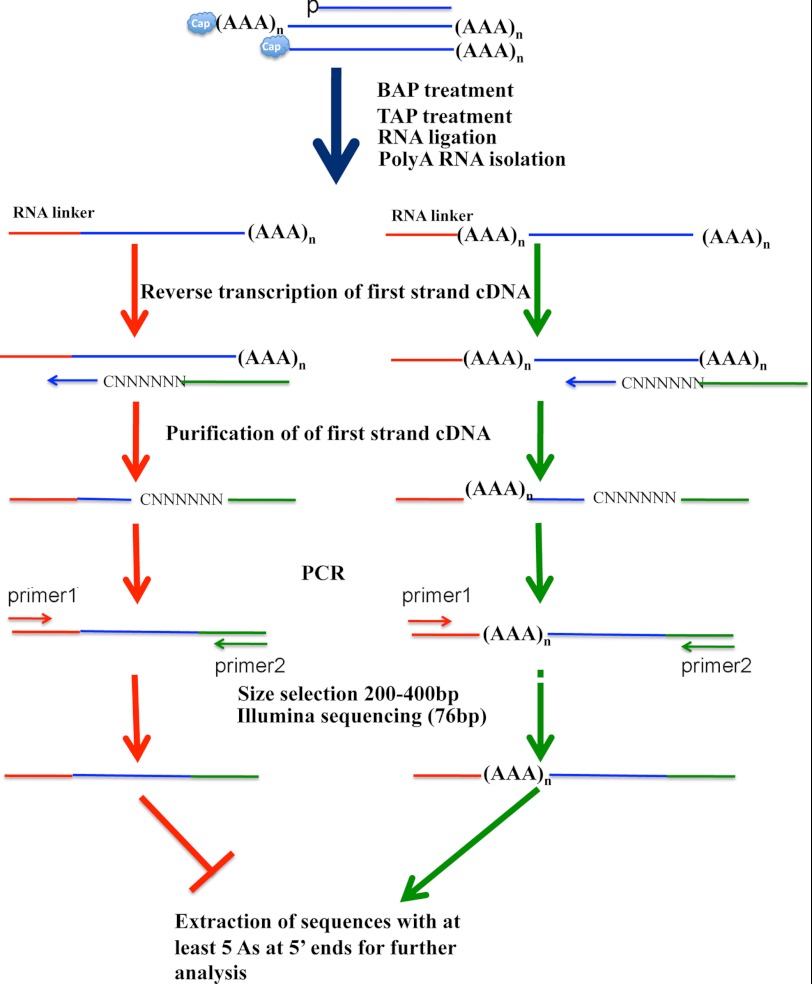

Generation of the Illumina cap analysis of gene expression library, sequencing, and data processing were described previously (14). Briefly, total RNA was treated with bacterial alkaline phosphatase and tobacco acid pyrophosphatase. Bacterial alkaline phosphatase treatment removes the 5′-phosphate of broken transcripts. Tobacco acid pyrophosphatase treatment removes the cap of intact mRNA, leaving a phosphate at the 5′-end for attaching a linker. The latter RNA was ligated to an RNA oligonucleotide (5′-ACACUCUUUCCCUACACGACGCUCUUCCGAUCUGG-3′) using T4 RNA ligase (TaKaRa, Clontech). The Dynabeads mRNA kit (Invitrogen) was used to isolate polyadenylated RNA. Random hexamer primers (with a C at their 3′-ends) attached to the Illumina adaptor (5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGCTCTTCCGATCTNNNNNNC-3′) were then used by reverse transcriptase (SuperScript II; Invitrogen) to synthesize first strand cDNA. The cDNA was amplified by PCR using primers 5′-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT-3′ and 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGCTCTTCCGATCT-3′. PCR products of 200–500 bp were gel-purified for Illumina GA IIx sequencing. More than 2.6 and 5.6 million reads mapping to the VACV genome were generated at 4 and 8 h, respectively. Reads with at least 5 As at their 5′-ends were extracted for further analysis. Those reads with 5′-poly(A) leaders that mapped to positions with 6 or more As on the genome were excluded from analysis.

Generation of a 3′-end library by sequencing by oligonucleotide ligation and detection was described previously (14). Briefly, double-stranded cDNA was prepared from polyadenylated mRNA using the SuperScript double-stranded cDNA synthesis kit as suggested by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). An anchored oligo(dT)16 primer with a GsuI restriction site was used for reverse transcription (5′-biotin-TEG-GAGAGAGAGACTGGAGT16VN-3′ where TEG is triethylene glycol; V is A, C, or G; and N is any nucleotide) was used for first strand synthesis. After steps described previously (14), the resulting DNA was amplified using primers 5′-CCACTACGCCTCCGCTTTCCTCTCTATG-3′ and 5′-CTGCCCCGGGTTCCTCATTCT-3′ for sequencing by oligonucleotide ligation and detection. The sequencing data were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number SRA054540.

Consensus Motif Generation and Search

The consensus motif of VACV promoters was generated using the multiple expectation maximization for motif elicitation program (28).

Transfection and Western Blotting

Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cell lysates for Western blotting were prepared with SDS-polyacrylamide gel loading buffer and resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, which were then blocked with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 for 1 h followed by incubation with primary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was washed three times with Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20 and then incubated with secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase or IRDye 800 antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was washed with Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20 and developed using chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) or a LI-COR Odyssey infrared imager (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

RESULTS

Strategy for Identification of TSSs

Cap analysis of gene expression methods were used to identify the capped 5′-ends of eukaryotic and viral mRNAs. A modified version of this procedure is depicted in Fig. 1. Total RNA was first treated to remove the 5′-phosphate on broken RNAs and prevent their subsequent sequencing. Next, the capped ends of intact RNAs were hydrolyzed to generate new 5′-phosphate ends that could be ligated to a specific oligoribonucleotide linker. Additional steps involved selection of polyadenylated RNAs, reverse transcription, PCR amplification, and deep sequencing. Although the oligoribonucleotide linker serves as a marker of the RNA 5′-ends, not all ends represent TSSs; other ends have been attributed to RNA cleavage and recapping or technical problems in the analysis (1, 29–31). To surmount this ambiguity and identify true TSSs, we took advantage of a conserved feature of intermediate and late VACV transcription, the presence of 3 or more consecutive A residues in the non-template DNA strand at the RNA start site (16, 32, 33). Mutagenesis studies have shown that the AAA sequence is an essential element of intermediate and late promoters (10, 12). Importantly, the propensity of the VACV RNA polymerase to slip on the AAA sequence during initiation of transcription results in a unique 5′-poly(A) leader containing additional A residues not encoded in the genome (15–19) that we have used as a signature of a genuine TSS (Fig. 1). In theory, non-templated As could be added during the reverse transcription or PCR step prior to sequencing. However, slippage by reverse transcriptase was not found in a previous study (34), and a threshold of 8 consecutive Ts are needed for slippage by Taq polymerase, and even then the frequency is very low (35). Although 5′-poly(A) leaders had only been demonstrated for relatively few VACV mRNAs, the ubiquity of the AAA sequence preceding intermediate and late ORFs suggested that this is a universal feature.

FIGURE 1.

Scheme for preparing cap analysis of gene expression library, deep sequencing, and selection of reads with 5′-poly(A) leaders. The starting total RNA is presumed to include broken cellular or viral RNAs with 5′-phosphate ends, capped RNA with 5′-poly(A) leaders, and capped RNA without poly(A) leaders. Treatment with bacterial alkaline phosphatase (BAP) removes the 5′-phosphate from broken RNA, whereas capped RNAs are protected. Treatment of capped RNAs with tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (TAP) removes the cap but leaves a 5′-phosphate that enables the ligation of an RNA linker. The polyadenylated RNA is then isolated and reverse transcribed using a random hexamer primer (NNNNNN) with a C at the 3′-end and attached to an Illumina adaptor (green) at the 5′-end. PCR is done with primers accommodating Illumina sequencing. Only sequences with at least 5 As preceding primer1 sequences are analyzed.

Genome-wide Mapping of TSSs

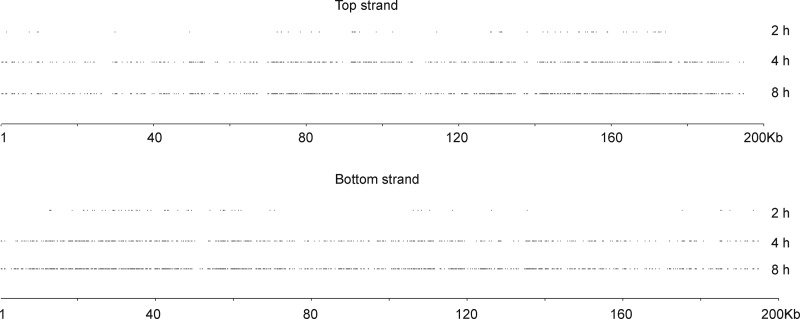

cDNA libraries were prepared as described in Fig. 1 from polyadenylated RNA isolated at 4 and 8 h after VACV infection at which times intermediate and late mRNAs predominate (5). The 76-nt reads allowed us to sequence through poly(A) leader sequences of about 50 nt or less. The reads that mapped to the VACV genome were filtered by excluding those that did not have at least 5 consecutive A residues at their 5′-ends (Fig. 1). We recovered 126,317 and 503,502 reads with 5 or more As at the 5′-ends that mapped to 1,714 and 2,736 sites in the VACV genome from the 4- and 8-h samples, respectively. A small number of reads that mapped to genomic regions with 6 or more consecutive As were excluded from further analysis. The 4- and 8-h TSSs were distributed throughout the length of the genome and on both DNA strands (Fig. 2). For comparison with early RNAs of which relatively few were thought to have 5′-poly(A) leaders (14, 36, 37), we reanalyzed the reads obtained at 2 h after infection (14). There was a total of 6,565 reads with 5 or more As at the TSSs, and they mapped to 145 sites located mostly near the right end of the top strand and the left end of the bottom strand (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of VACV TSSs containing poly(A) leaders determined at different times after infection. RNA was isolated at 2, 4, and 8 h after infection. The TSSs containing poly(A) leaders were aligned with the top and bottom DNA strands. The genome nucleotide numbers are below each strand in kilobases (kb).

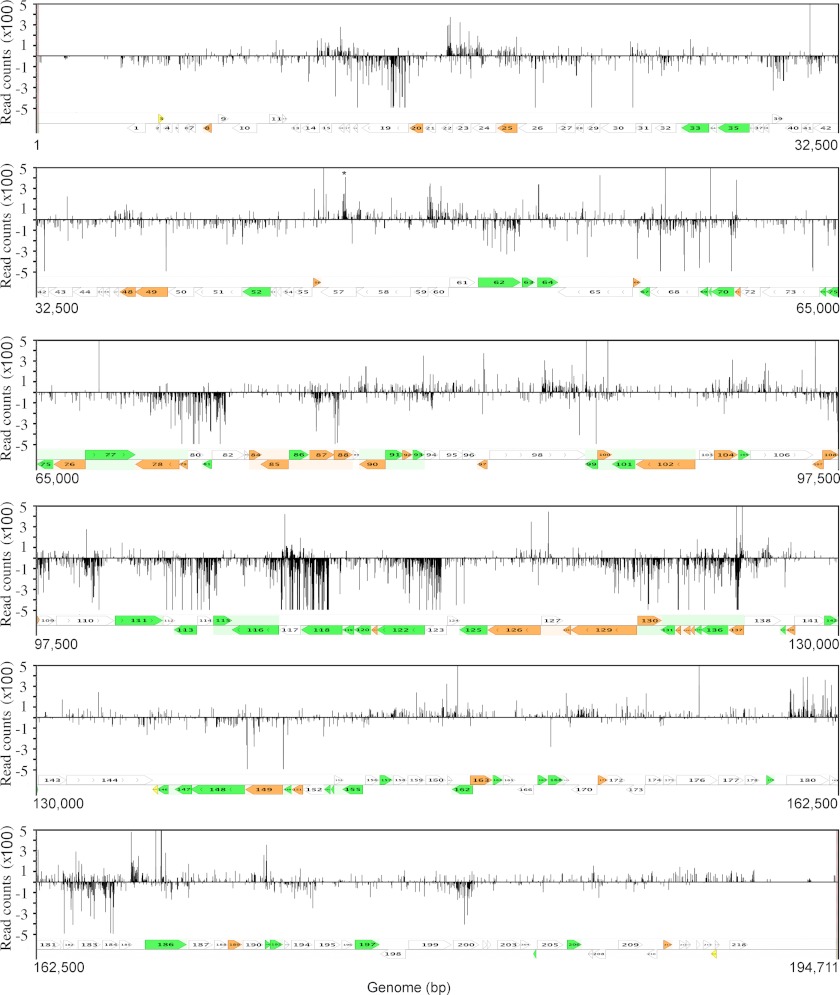

The 195,000-bp, linear, double-stranded VACVWR genome contains ∼200 ORFs and is organized with predominantly early genes near the two ends and intermediate and late genes with intermixing of some early genes in the central region. Translated ORFs are present on both strands, although there is little overlap and a tendency for transcription to occur toward the nearer end of the genome. In Fig. 3, TSS data from the 8-h sample is shown. The lengths of the lines indicate the number of reads in hundreds; upward lines are transcribed from the top DNA strand in the rightward direction, and downward lines are transcribed from the bottom DNA strand in the leftward direction. The red lines indicate 5′-ends that map within 25 nt upstream of annotated ORFs and are therefore very likely to represent their TSSs, although further upstream TSSs may also be used. The paucity of PR genes near the two ends of the genome accounts for the very few TSSs that map close to ORFs in those regions. The blue lines include 5′-ends that are further upstream of ORFs next to pseudogenes, within ORFs, and in non-coding regions and are collectively referred to as anomalous TSSs. There was a wide range in the number of read counts for individual TSSs close to annotated ORFs as well as at anomalous sites. Because the mRNAs represent steady state levels, the variation could reflect differences in RNA synthesis or stability. With regard to the latter, studies have suggested that the half-lives of total PR RNAs could be less than 15 min (38, 39).

FIGURE 3.

Genome-wide map of 5′-ends of VACV mRNAs with poly(A) leaders. The library was prepared from RNA isolated at 8 h after infection. The read counts of 5′-ends mapping to the top and bottom strands of the genome are displayed above and below the horizontal line, respectively. Red lines indicate sites located within 25 nt upstream of start codons of annotated ORFs. Blue lines indicate all other sites. For display purposes, the highest counts are off scale. Numbered arrows pointing in the directions of transcription indicate VACVWR ORFs. The expression classes are indicated by colors (white, early; green, intermediate; orange, late; yellow, expression not detectable).

Analysis of TSSs Upstream of PR ORFs

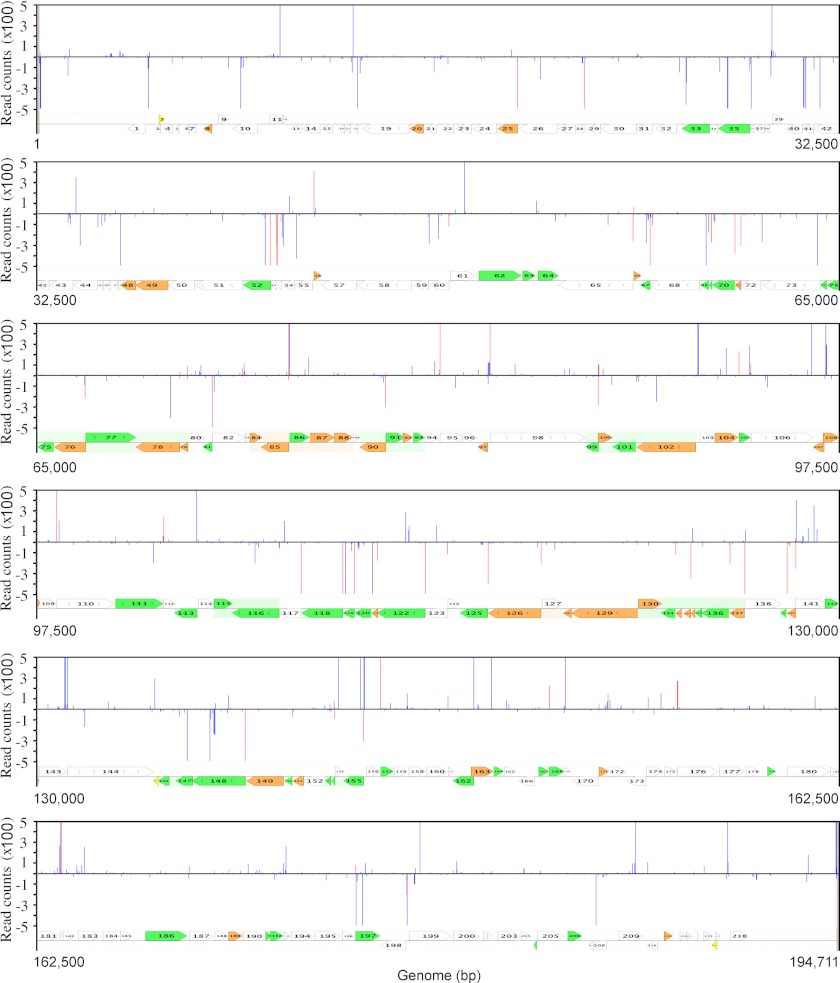

TSSs were documented upstream of 90 of the 93 previously annotated intermediate and late PR ORFs (Table 1). TSSs were identified within 25 nt upstream of the start codons of 75 PR ORFs, and for 53 of these, there were no additional nucleotides between the TSS and the translation initiation codon, underscoring the frequency of the promoter motif TAAATG. A TSS was between 25 and 100 nt upstream of initiation methionines of 15 ORFs (Table 1). In several of the latter, there was an additional, apparently silent AAA sequence between the TSS and the translation initiation codon. The distances between the 5′-ends of the RNAs and translation initiation codons are shown in Fig. 4A and Table 1.

TABLE 1.

TSS locations of VACV postreplicative genes

The nearest TSS to the ORF within 100 nt upstream of start codon was annotated using data from mRNAs with at least 5 As at 5′-ends.

| VACVWR no. | COP namea | TEb | TSSc | Countsd | De |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 003f | No ortholog | ND | None | ||

| 008f | C19L | L | None | ||

| 020g | C8L | L | 15683 | 14 | 40 |

| 25 | C3L | L | 19469 | 8,481 | 2 |

| 33 | K2L | I | 27258 | 15 | 3 |

| 35 | K4L | I | 28897 | 138 | 0 |

| 48 | F9L | L | 36471 | 26 | 0 |

| 49 | F10L | L | 37777 | 7 | 0 |

| 52 | F13L | I | 41948 | 540 | 0 |

| 56 | F17R | L | 43703 | 415 | 0 |

| 62 | E6R | I | 50321 | 7 | 78 |

| 063g | E7R | I | 52184 | 2 | 0 |

| 64 | E8R | I | 52804 | 40 | 5 |

| 66 | E10R | L | 56689 | 68 | 0 |

| 67 | E11L | I | 57358 | 32,408 | 0 |

| 69 | O2L | I | 59727 | 180 | 8 |

| 69.5 | O3L | I | 59852 | 274 | 2 |

| 70 | I1L | I | 60803 | 380 | 0 |

| 71 | I2L | L | 61031 | 39 | 0 |

| 74 | I5L | I | 64505 | 65 | 0 |

| 75 | I6L | I | 65678 | 1 | 6 |

| 76 | I7L | L | 66936 | 224 | 0 |

| 77 | I8R | I | 66921 | 2 | 23 |

| 78 | G1L | L | 70751 | 26 | 0 |

| 79 | G3L | L | 71083 | 30 | 0 |

| 81 | G4L | I | 72083 | 3,035 | 0 |

| 084g | G6R | L | 73541 | 1 | 52 |

| 85 | G7L | L | 75168 | 38 | 0 |

| 86 | G8R | I | 75201 | 21,378 | 0 |

| 87 | G9R | L | 76001 | 178 | 2 |

| 88 | L1R | L | 77026 | 37 | 0 |

| 90 | L3L | L | 79113 | 309 | 0 |

| 91 | L4R | I | 79140 | 19 | 0 |

| 92 | L5R | L | 79905 | 1 | 0 |

| 93 | J1R | I | 80248 | 3 | 0 |

| 97 | J5L | L | 83266 | 15 | 10 |

| 99 | H1L | I | 87736 | 289 | 0 |

| 100 | H2R | L | 87752 | 106 | 0 |

| 101 | H3L | I | 89296 | 60 | 0 |

| 102 | H4L | L | 91684 | 5 | 0 |

| 104 | H6R | L | 92484 | 7 | 0 |

| 105 | H7R | I | 93465 | 233 | 0 |

| 107 | D2L | L | 96880 | 3 | 0 |

| 108g | D3R | L | 96847 | 3 | 28 |

| 111 | D6R | I | 100674 | 48 | 0 |

| 113f | D8L | I | None | ||

| 115 | D10R | I | 104656 | 4 | 0 |

| 116 | D11L | I | 107296 | 48 | 0 |

| 118 | D13L | I | 109887 | 521 | 7 |

| 119 | A1L | I | 110356 | 2,145 | 0 |

| 120g | A2L | I | 111083 | 1,988 | 32 |

| 121 | A2.5L | L | 111278 | 176 | 0 |

| 122 | A3L | I | 113230 | 1,799 | 3 |

| 125 | A6L | I | 115775 | 405 | 3 |

| 126 | A7L | L | 117930 | 204 | 2 |

| 128g | A9L | L | 119248 | 2 | 81 |

| 129 | A10L | L | 121843 | 23 | 0 |

| 130 | A11R | L | 121860 | 6 | 0 |

| 131 | A12L | I | 123394 | 114 | 0 |

| 132 | A13L | L | 123630 | 8 | 0 |

| 133 | A14L | L | 124010 | 349 | 0 |

| 134 | A14.5L | L | 124188 | 2 | 0 |

| 135 | A15L | I | 124462 | 36 | 0 |

| 136 | A16L | I | 125579 | 23 | 0 |

| 137 | A17L | L | 126193 | 4,676 | 0 |

| 139 | A19L | I | 127903 | 16,840 | 0 |

| 140 | A21L | L | 128273 | 255 | 16 |

| 142 | A22R | I | 129444 | 3 | 24 |

| 145g | No ortholog | ND | 134989 | 31 | 99 |

| 146g | No ortholog | I | 135359 | 3 | 36 |

| 147g | No ortholog | I | 136314 | 3 | 36 |

| 148 | A25L | I | 138415 | 850 | 0 |

| 149 | A26L | L | 139962 | 5 | 0 |

| 150 | A27L | I | 140344 | 72 | 0 |

| 151 | A28L | L | 140785 | 4 | 0 |

| 153 | A30L | I | 141899 | 20 | 0 |

| 153.5 | A30.5L | I | 142051 | 86 | 0 |

| 155 | A32L | I | 143220 | 311 | 8 |

| 157 | A34R | I | 143913 | 2,290 | 0 |

| 162g | A38L | I | 147718 | 3 | 32 |

| 163g | A39R | L | 147528 | 2 | 63 |

| 164g | A39R | I | 148416 | 589 | 59 |

| 167 | A42R | I | 150323 | 17 | 6 |

| 168 | A43R | I | 150768 | 226 | 0 |

| 171 | A45R | L | 152778 | 50 | 3 |

| 179 | A53R | I | 159602 | 7 | 20 |

| 186 | B4R | I | 166588 | 4 | 7 |

| 189 | B7R | L | 169969 | 34 | 0 |

| 191g | B9R | I | 171425 | 1 | 52 |

| 192g | B10R | I | 171576 | 4 | 97 |

| 197 | B16R | I | 175114 | 80 | 5 |

| 204.5 | 264 | I | 182471 | 3 | 3 |

| 206g | C13L | I | 183702 | 7 | 33 |

| 4 | C22L | E | 5462 | 69 | 3 |

| 15 | No ortholog | E | 11951 | 1 | 7 |

| 28 | N1L | E | 22189 | 1,057 | 18 |

| 30 | M1L | E | 24306 | 1 | 11 |

| 37 | K5L | E | 29488 | 16 | 10 |

| 42 | F3L | E | 32946 | 2 | 0 |

| 43 | F4L | E | 33921 | 25 | 5 |

| 46 | F7L | E | 35443 | 19 | 15 |

| 53 | F14L | E | 42209 | 572 | 22 |

| 53.5 | F14.5L | E | 42386 | 77 | 0 |

| 57 | E1L | E | 45451 | 4 | 9 |

| 59 | E3L | E | 48351 | 28 | 0 |

| 60 | E4L | E | 49186 | 122 | 0 |

| 65 | E9L | E | 56655 | 266 | 0 |

| 68 | O1L | E | 59369 | 12 | 24 |

| 73 | I4L | E | 64239 | 5 | 0 |

| 80 | G2R | E | 71077 | 88 | 0 |

| 83 | G5.5R | E | 73379 | 117 | 21 |

| 95 | J3R | E | 81324 | 5,108 | 0 |

| 98 | J6R | E | 83366 | 7,801 | 0 |

| 106 | D1R | E | 93942 | 111 | 7 |

| 109 | D4R | E | 97569 | 11 | 19 |

| 110 | D5R | E | 98276 | 2,070 | 0 |

| 112 | D7R | E | 102614 | 245 | 0 |

| 117 | D12L | E | 108194 | 1,118 | 0 |

| 123 | A4L | E | 114125 | 112 | 0 |

| 124 | A5R | E | 114165 | 95 | 0 |

| 138 | A18R | E | 126210 | 133 | 0 |

| 141 | A20R | E | 128251 | 33 | 7 |

| 161 | Pseudogene | E | 146658 | 126 | 12 |

| 169 | 268 | E | 151335 | 24 | 25 |

| 172 | A46R | E | 153138 | 69 | 10 |

| 175 | A49R | E | 155414 | 9 | 24 |

| 176 | A50R | E | 155959 | 275 | 0 |

| 181.5 | 269 | E | 163146 | 125,667 | 0 |

| 187 | B5R | E | 168369 | 71 | 7 |

| 194 | B12R | E | 172506 | 2 | 24 |

| 200 | B19R | E | 179079 | 24 | 24 |

| 202 | B20R | E | 180470 | 1 | 13 |

| 204 | No ortholog | E | 181829 | 10 | 11 |

a ORF name used for Copenhagen (COP) strain of VACV.

b The temporal expression (TE) class was determined previously (5, 9, 14). ND, not detected; L, late; I, intermediate; E, early.

c Position of first non-A nucleotide at which TSS mapped.

d Counts were from 8-h data only unless only 0, 1, or 2 counts were found at 8 h.

e Distance between TSS and start of ORF in nucleotides.

f No TSS within 100 nt upstream of start codon identified.

g TSS located at more than 25 nt upstream of start codon.

FIGURE 4.

Distances between TSSs and start codons of PR genes (A) and number of As in 5′-poly(A) leaders of intermediate, late, and anomalous RNAs (B).

The number of As in the poly(A) leader varied even for those mapping to the same site. The longest poly(A) leader contained 51 As. However, poly(A) leaders with additional As would not be mapped because of the relatively short reads obtained by Illumina sequencing. The most frequent lengths of the poly(A) leaders in the transcripts of intermediate and late ORFs were 8 and 11 As, respectively (Fig. 4B). These numbers are in the range found previously by direct analysis of poly(A) leader lengths (18). However, the anomalous transcripts described below had shorter poly(A) leaders (Fig. 4B).

To estimate the frequency of slippage during transcription initiation, we determined the number of 8-h reads with less than 5 As that mapped to the AAA sequences of the 90 TSSs preceding PR ORFs. We found 6,230 reads with less than 5 As compared with 103,722 with 5 or more As. Thus, slippage occurred at nearly 95% of initiations at these sites. Although heretofore the presence of 5′-poly(A) leaders had only been demonstrated for relatively few mRNAs, the present study indicated that this is a general feature of PR transcripts. At 4 and 8 h after infection, we also found TSSs of RNAs with 5′-poly(A) leaders within 25 nt upstream of start codons of 40 genes that are expressed prior to DNA replication (Table 1), suggesting that slippage also occurs at early stages of gene expression or that these early promoters also contain functional intermediate or late promoter elements.

Analysis of TSSs in Anomalous Locations

The TSSs classified as anomalous could be grouped into several categories. For example, VACVWR ORFs 145–148 (Fig. 3) are fragments of the large A-type inclusion protein ORF of cowpox virus. ORF 148 is homologous to the N-terminal region of the cowpox virus protein and is expressed as the VACV A25 intermediate protein, whereas ORFs 147, 146, and 145 are homologous to the C-terminal region, and therefore transcription initiation might be biologically irrelevant. Nevertheless, we found TSSs 36 nt upstream of ORFs 147 and 146 and 99 nt upstream of ORF 145 (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Similarly, TSSs were found preceding VACVWR ORFs 163 and 164 (Fig. 3 and Table 1) corresponding to the N- and C-terminal interrupted portions of the complete semaphorin ORF in the Copenhagen strain of VACV. These results explain our previous findings that ORFs 146, 147, and 164 can be expressed from transfected plasmids under control of their natural upstream DNA sequences in VACV-infected cells (9). We also demonstrated by Western blotting that the protein encoded by ORF 147 with a 3×FLAG tag coding sequence added at the C terminus of ORF 147 in the VACV genome was expressed (data not shown).

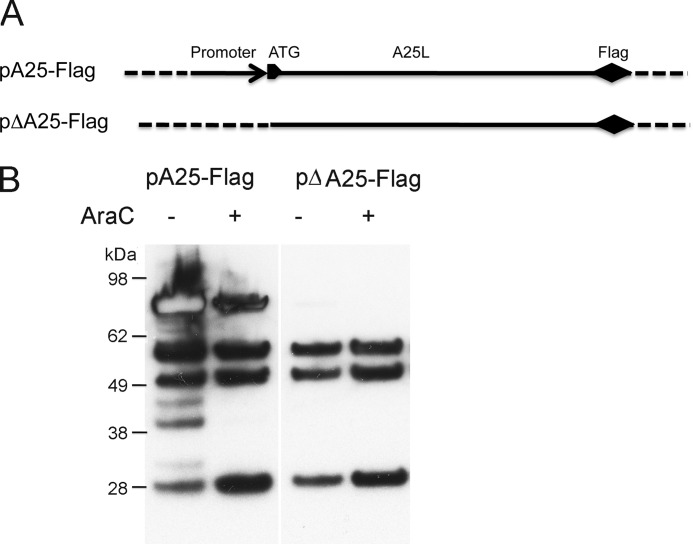

Fig. 3 shows many examples of TSSs within ORFs. The anomalous TSSs were more commonly mapped to the sense strand than the antisense strand. RNAs that are initiated within ORFs have the potential to be translated into shorter isoforms of proteins. We examined ORF 148 (encoding the A25 protein), one of the longest ORFs in the VACVWR genome, to test this possibility. Plasmids containing ORF 148 with a C-terminal FLAG tag with or without its natural promoter were constructed (Fig. 5A). The plasmids were transfected into cells infected with VACV in the presence or absence of the DNA replication inhibitor AraC. The inhibitor was used to discriminate between intermediate and late promoters. Intermediate transcription occurs from transfected DNA templates in the absence of viral DNA replication because intermediate transcription factors are products of early genes; in contrast, late transcription is blocked because late transcription factors are not made under these conditions (12, 40, 41). Thus, protein expression from a transfected plasmid in the presence of AraC is indicative of an intermediate promoter. The expression of intermediate promoters in the absence of AraC can vary. However, expression exclusively in the absence of AraC is indicative of a late promoter. The cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-FLAG antibody. Four major bands were detected from cells transfected with the plasmid containing the promoter upstream of ORF 148 in the presence and absence of AraC (Fig. 5B). The few additional bands present in the absence of AraC might have resulted from protein cleavage under conditions of viral late protein synthesis. Importantly, without the upstream promoter sequence, the three lower bands were still detected, indicating the presence of internal promoters within the long ORF (Fig. 5B). The nearest TSSs that could initiate the mRNAs for these isoforms were at bp 138301, 137636, and 136986 in the bottom strand of the VACV genome, respectively. The promoters were classified as intermediate based on expression in the presence of AraC.

FIGURE 5.

Experimental evidence for promoters associated with internal TSSs in VACVWR ORF 148 (A25L). A, schematic diagram of plasmids pA25-FLAG and pΔA25-FLAG in which the promoter and translation start site of ORF A25L are present and absent, respectively. B, Western blot of proteins detected with anti-FLAG antibody from cell lysates derived from BS-C-1 cells infected with VACV in the presence or absence of AraC and transfected with pA25-FLAG or pΔA25-FLAG. The positions of protein size markers are shown in kDa at the left.

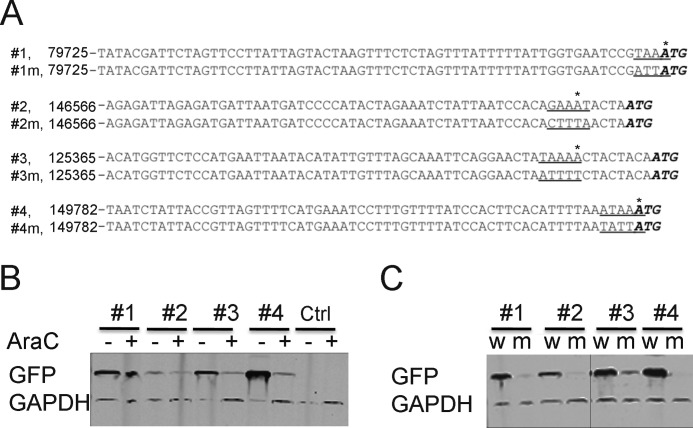

Some TSSs were very close to the start codons of previously unannotated small ORFs. Four examples of such ORFs that are conserved in other orthopoxviruses were further analyzed (supplemental Fig. S1). The four ORFs with a 3×FLAG tag appended to the C terminus and ∼50 bp of upstream sequence were inserted into plasmids. The plasmids were transfected into VACV-infected BS-C-1 cells, and the lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. However, no proteins were detected by anti-FLAG antibody (not shown). Because this result could be due to failure of transcription/translation or protein instability, we made additional plasmids with the 50-bp putative promoter sequences upstream of GFP. Two sets of plasmids were made: one set had the natural upstream sequences, and the other set had mutations predicted to inactivate the putative promoter (Fig. 6A). The cells were infected with VACV in the absence or presence of AraC to differentiate between intermediate and late promoters. GFP was detected by Western blotting, and much higher expression was demonstrated in the absence of AraC for at least two of the promoters, indicating that they can be classified as late (Fig. 6B). Mutation of the AAA promoter element and surrounding nucleotides (Fig. 6A) abolished GFP expression in each case (Fig. 6C), confirming that functional promoters regulated the anomalous TSSs even though protein expression of the short ORFs had not been detected.

FIGURE 6.

Experimental evidence for promoters associated with previously unannotated small ORFs. A, nucleotide sequences of putative promoters associated with TSSs preceding four unannotated small ORFs. Genome locations are indicated at the left. Top, natural sequence; bottom, sequence with mutations. Underlined nucleotides indicate AAA promoter elements or the corresponding mutated sequences. The bold italicized ATGs indicate the start codons of the associated ORFs. The asterisks above the sequences indicate the anomalous TSSs. B, Western blot detection of GFP from lysates of BS-C-1 cells infected with VACV in the presence or absence of AraC and transfected with plasmids containing natural promoter sequences 1, 2, 3, and 4 in A preceding GFP ORF or promoterless control (Ctrl) plasmid. GAPDH was detected with antibody as a loading control. C, Western blot detection of GFP from lysates of BS-C-1 cells infected with VACV and transfected with plasmids containing the natural (w) or mutated (m) promoters indicated in A. GAPDH was detected as a loading control.

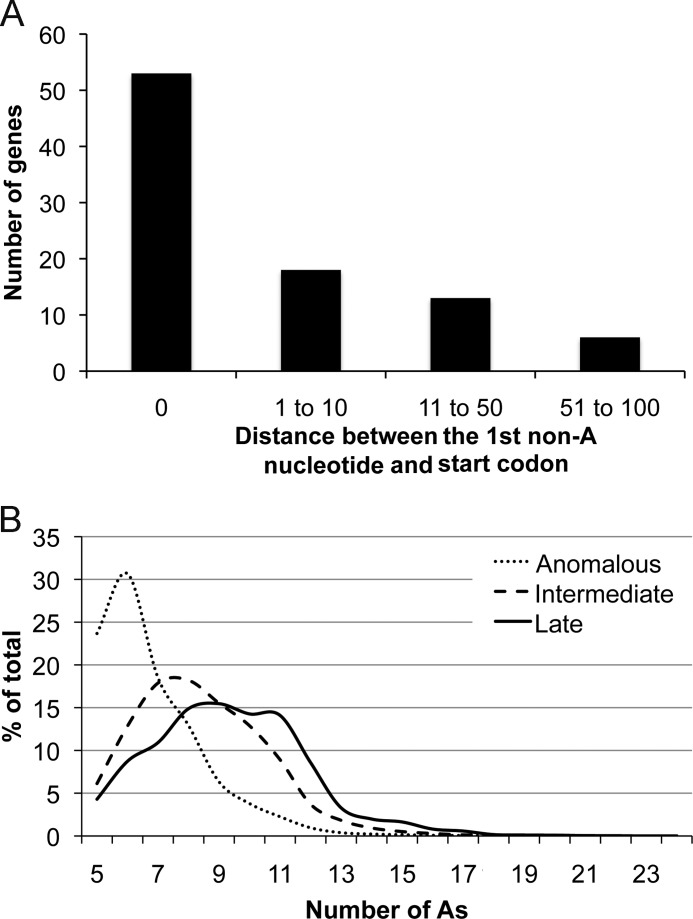

Comparison of Sequences Adjacent to TSSs

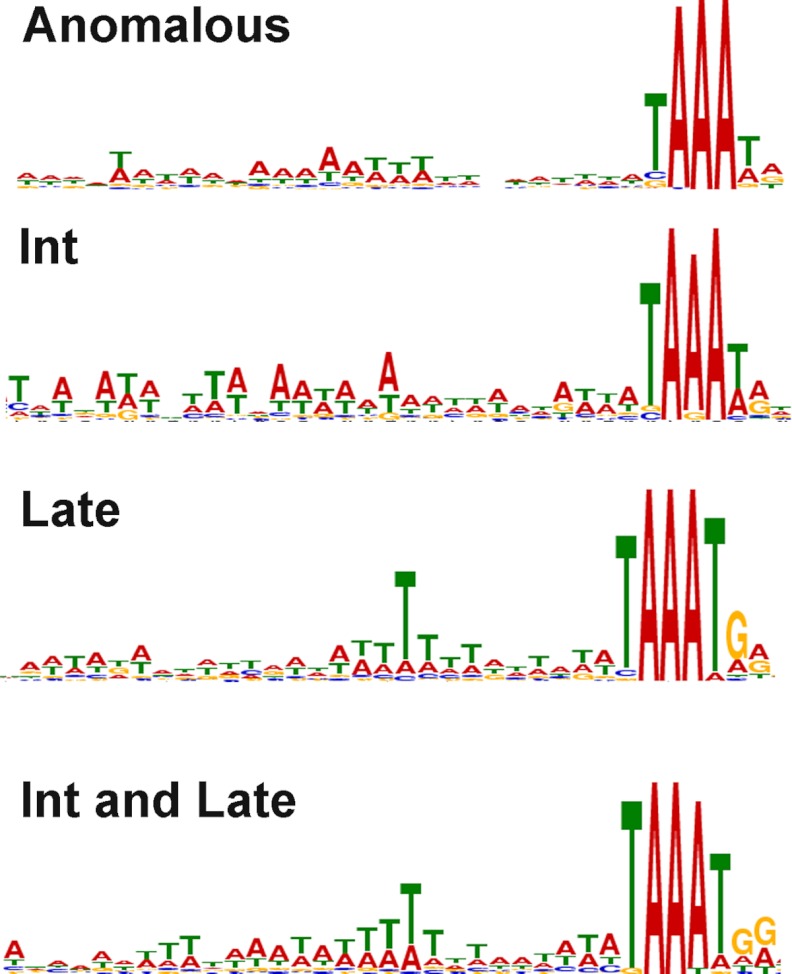

We were interested in comparing the sequences upstream of the TSSs at anomalous locations with those of the annotated VACVWR ORFs. In our previous expression profiling of VACV intermediate and late genes, we characterized their consensus promoter motifs by analysis of sequences upstream of the ORFs (9). The present determination of TSSs allowed a more precise and confident search for consensus sequences. Compared with the previous results, the refined late class consensus had a more conserved TG following TAAA and a more conserved T at 10 nt upstream of TAAA, whereas the intermediate class had a more AT-rich sequence (with a preference for As) ∼15–25 nt upstream of TAAA (Fig. 7). The most frequent nucleotide preceding and following AAA was found to be T for both classes. A third class of ORFs appeared to be expressed strongly at both intermediate and late times and resembled the late motif with regard to T residues (Fig. 7). The promoter motif derived for the sequences upstream of the unannotated TSSs with more than 100 reads was similar to that of a mixture of intermediate and late promoters at annotated ORFs (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

Promoter consensus sequences. Promoter motifs were generated with the multiple expectation maximization for motif elicitation program from the 50-nt sequences upstream of anomalous TSSs and TSSs corresponding to intermediate (Int), late, and intermediate/late ORFs.

Analysis of PR 3′-Polyadenylation Sites (PASs)

The 3′-ends of early and PR mRNAs appear to be formed by distinct mechanisms. Biochemical studies indicated that early mRNAs terminate within 50 nt after a UUUUUNU sequence and are subsequently polyadenylated (42, 43), although recent sequence analyses indicate that this does not account for all 3′-polyadenylated ends (14). In contrast, the VACV PR transcription apparatus does not recognize UUUUUNU as a termination sequence, and the late mRNAs are heterogeneous in size (20, 21). Although a few PR mRNAs have been shown to be processed by cleavage (44–47), the situation for the majority is unknown. A previously described scheme used to isolate the RNA sequences adjacent to the 3′-poly(A) tails of early mRNAs (14) was adapted for RNAs made at 4 and 8 h after infection. A biotinylated poly(dT), dinucleotide-anchored primer with a GsuI type IIs restriction endonuclease site was used for reverse transcription. The anchor comprised all possible dinucleotide pairs, ensuring that reverse transcription did not initiate further within the poly(A) tail, which would have resulted in cDNAs too long for high throughput sequence analysis. After second strand synthesis, the cDNA was cleaved with GsuI to leave two As marking the original poly(A) site (14). After additional steps, the short DNA fragments were sequenced. A total of 103,340 and 704,615 reads were mapped to 7,221 and 16,931 sites on the VACV genome at 4 and 8 h after infection, respectively. Thus, the number of PASs was about 5 times the number of TSSs containing 5′-poly(A) leaders. Data from the 8-h sample were plotted relative to an ORF map in Fig. 8. The PASs were predominantly on the same strand as the nearby TSSs and appeared to occur in clusters.

FIGURE 8.

VACV genome-wide PAS map. PASs were determined by sequencing cDNAs prepared from polyadenylated RNAs isolated at 8 h after infection. The reads mapping to the top and bottom DNA strands are displayed above and below the horizontal line, respectively. The arrows indicate the directions of transcription of the ORFs. The asterisk indicates the position of many polyadenylated 3′-ends identified in this study that overlapped the described cleavage site downstream of the F17R (VACWR056) ORF (47). Numbered arrows pointing in the directions of transcription indicate VACVWR ORFs. The expression classes are indicated by colors (white, early; green, intermediate; orange, late; yellow, expression not detectable).

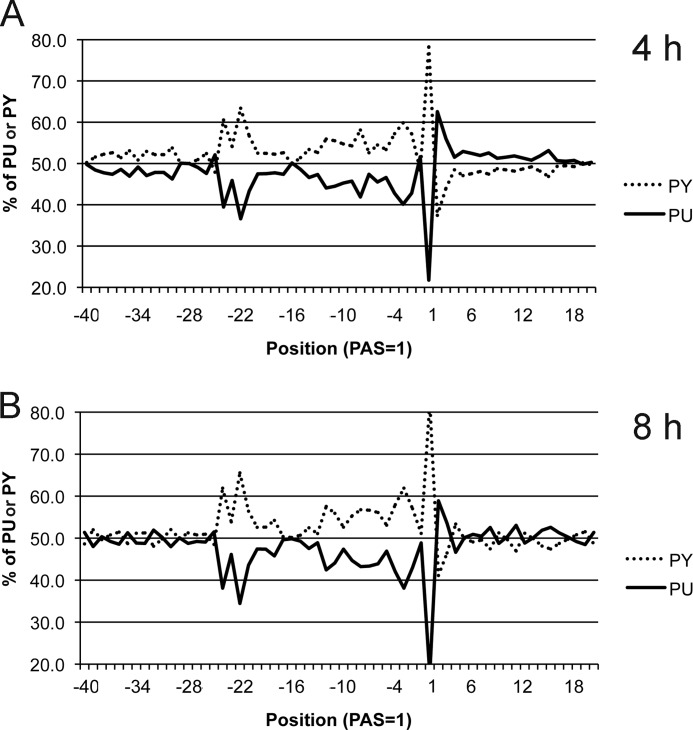

We had found previously that coding strand sequences upstream of the PASs of early RNAs were pyrimidine-rich regardless of the presence of the UUUUUNU termination motif (14). A pyrimidine-rich sequence was also found in RNAs at 4 and 8 h after infection (Fig. 9). The presence of the UUUUUNU early termination sequence was infrequent even when the 64 most abundant PASs accounting for >0.1% of the total were examined.

FIGURE 9.

Pyrimidine (PY) and purine (PU) frequencies surrounding PASs. The PAS read counts with more than 0.01% of the total at 4 or 8 h were used for analysis.

DISCUSSION

The presence of a 5′-poly(A) leader is a feature of VACV PR transcripts that results from slippage of the RNA polymerase at the conserved AAA sequence of PR promoters. We took advantage of this trait to distinguish true TSSs from processed 5′-ends. Using this criterion, TSSs were mapped just upstream of 90 of the 93 previously annotated intermediate and late ORFs. Approximately 95% of the transcripts from these sites had poly(A) leaders of at least 5 nucleotides. The median lengths of 5′-poly(A) for intermediate and late mRNAs were 8 and 11, respectively. As an A of the ATG translation initiation codon frequently overlaps the TAAAT promoter sequence, slippage provides a leader that could enhance translation (48, 49). Poly(A) leaders occur in some yeast mRNAs, and the protein synthesis rate increases with the length of the poly(A) leader until about 12 residues and then decreases dramatically possibly because of association of the poly(A)-binding protein (50). The VACV poly(A) leaders formed at the anomalous TSSs were generally shorter, suggesting that they may not be optimal for translation.

Unexpectedly, the number of TSSs with poly(A) leaders greatly exceeded the number of annotated VACV ORFs, and many mapped within or far upstream of coding regions or adjacent to pseudogenes. Indeed, about 25% of the genomic AAA sequences are used as TSSs. The anomalous TSSs occurred more often on the sense strand than on the antisense strand. This could result from a tendency of the RNA polymerase to remain associated with the DNA after transcription termination and then reinitiating at a downstream site. This scenario could also account for the clustering of ORFs on the same strand.

The 3′-ends of VACV RNAs were identified by sequencing non-templated A residues, which were added by the virus-encoded poly(A) polymerase (51, 52). The VACV poly(A) polymerase has little sequence specificity except for multiple U residues 30–40 nt upstream of the 3′-end (53). Polyadenylation of the 3′-ends of VACV early mRNAs has been well studied and often occurs following termination, which is mediated by VACV-encoded enzymes working in conjunction with the RNA polymerase at 25–50 nt after a UUUUUNU sequence (42, 54, 55). Additional polyadenylated 3′-ends occur immediately after a pyrimidine-rich sequence (14). Much less is known about 3′-end formation of VACV PR mRNAs, which are extremely heterogeneous in length (20, 21). The UUUUUNU termination sequence of early mRNAs is not recognized in PR transcripts, and the present study is the first to provide a global analysis of their 3′-ends. Our finding of a very large number of distinct polyadenylated 3′-ends was consistent with the heterogeneity of PR RNAs and suggested the absence of a highly specific recognition motif. However, we did note the consistent occurrence of a pyrimidine-rich sequence in the coding strand immediately upstream of postreplicative PASs that was similar to that of early PASs that were not preceded by the UUUUUNU signal. The possible role of the VACV-encoded NPH-II in early mRNA termination was suggested by the generation of abnormally long early RNAs by NPH-II-defective virions (56). NPH-II has DNA- and RNA-dependent triphosphate phosphohydrolase and RNA helicase activities (57–59). Furthermore, NPH-II can efficiently unwind a DNA-RNA hybrid containing a pyrimidine-rich DNA tracking strand (60), which as shown here precedes PR PASs. Thus, NPH-II may be involved in termination of PR and early transcripts.

Several poxvirus PR mRNAs are processed at specific sites by cleavage (45–47, 61, 62). The VACV-encoded H5 protein or a protein associated with it has been implicated in processing of the F17R (VACWR056) transcript (46). We found many polyadenylated 3′-ends (indicated with an asterisk in Fig. 8) that overlapped the described cleavage site downstream of the 056 ORF rather than a single predominant end (47).

The most interesting and surprising result of this study was the complexity of transcription as revealed by the enormous number of TSSs. These anomalous transcripts could have a variety of roles. As proof of principal, we showed that transcriptional initiations within a long VACVWR ORF resulted in multiple shorter protein isoforms and that functional promoters preceded pseudogenes arising from frameshift mutations and other anomalous TSSs. However, in some cases, we could not demonstrate a protein product associated with anomalous TSSs because of either non-translatability or instability even though reporter gene expression from those promoters occurred. Numerous studies have shown that non-coding RNAs have important regulatory functions in prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms (63–65), and it is intriguing to think that some VACV RNAs may also have non-coding functions. Pervasive transcription initiation may also enable poxviruses to express new genes from endogenous or horizontally acquired cellular DNA during evolution. Indeed, there are many examples of viral homologs of cellular genes that have likely been captured from their hosts and modified for immune defense (66).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Catherine Cotter for cell culture maintenance and the National Institutes of Health Fellows Editorial Board for assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant ZIA A1000307-31 from the Division of Intramural Research, NIAID.

The sequencing data were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number SRA054540.

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- VACV

- vaccinia virus

- PAS

- polyadenylation site

- PR

- postreplicative

- TSS

- transcription start site

- WR

- Western Reserve

- nt

- nucleotide(s)

- NPH-II

- nucleoside-triphosphate phosphohydrolase II.

REFERENCES

- 1. ENCODE Project Consortium (2007) Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature 447, 799–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carninci P., Yasuda J., Hayashizaki Y. (2008) Multifaceted mammalian transcriptome. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 274–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. David L., Huber W., Granovskaia M., Toedling J., Palm C. J., Bofkin L., Jones T., Davis R. W., Steinmetz L. M. (2006) A high-resolution map of transcription in the yeast genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 5320–5325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. He Y., Vogelstein B., Velculescu V. E., Papadopoulos N., Kinzler K. W. (2008) The antisense transcriptomes of human cells. Science 322, 1855–1857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang Z., Bruno D. P., Martens C. A., Porcella S. F., Moss B. (2010) Simultaneous high-resolution analysis of vaccinia virus and host cell transcriptomes by deep RNA sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 11513–11518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Legendre M., Audic S., Poirot O., Hingamp P., Seltzer V., Byrne D., Lartigue A., Lescot M., Bernadac A., Poulain J., Abergel C., Claverie J. M. (2010) mRNA deep sequencing reveals 75 new genes and a complex transcriptional landscape in Mimivirus. Genome Res. 20, 664–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhao H., Dahlö M., Isaksson A., Syvänen A. C., Pettersson U. (2012) The transcriptome of the adenovirus infected cell. Virology 424, 115–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moss B. (2007) in Fields Virology (Knipe D. M., Howley P. M., eds) pp. 2905–2946, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang Z., Reynolds S. E., Martens C. A., Bruno D. P., Porcella S. F., Moss B. (2011) Expression profiling of the intermediate and late stages of poxvirus replication. J. Virol. 85, 9899–9908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davison A. J., Moss B. (1989) The structure of vaccinia virus late promoters. J. Mol. Biol. 210, 771–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davison A. J., Moss B. (1989) The structure of vaccinia virus early promoters. J. Mol. Biol. 210, 749–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baldick C. J., Jr., Keck J. G., Moss B. (1992) Mutational analysis of the core, spacer and initiator regions of vaccinia virus intermediate class promoters. J. Virol. 66, 4710–4719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Knutson B. A., Liu X., Oh J., Broyles S. S. (2006) Vaccinia virus intermediate and late promoter elements are targeted by the TATA-binding protein. J. Virol. 80, 6784–6793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang Z., Bruno D. P., Martens C. A., Porcella S. F., Moss B. (2011) Genome-wide analysis of the 5′ and 3′ ends of vaccinia virus early mRNAs delineates regulatory sequences of annotated and anomalous transcripts. J. Virol. 85, 5897–5909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bertholet C., Van Meir E., ten Heggeler-Bordier B., Wittek R. (1987) Vaccinia virus produces late mRNAs by discontinuous synthesis. Cell 50, 153–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schwer B., Visca P., Vos J. C., Stunnenberg H. G. (1987) Discontinuous transcription or RNA processing of vaccinia virus late messengers results in a 5′ poly(A) leader. Cell 50, 163–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Patel D. D., Pickup D. J. (1987) Messenger RNAs of a strongly-expressed late gene of cowpox virus contains a 5′-terminal poly(A) leader. EMBO J. 6, 3787–3794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ahn B. Y., Moss B. (1989) Capped poly(A) leader of variable lengths at the 5′ ends of vaccinia virus late mRNAs. J. Virol. 63, 226–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baldick C. J., Jr., Moss B. (1993) Characterization and temporal regulation of mRNAs encoded by vaccinia virus intermediate stage genes. J. Virol. 67, 3515–3527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cooper J. A., Wittek R., Moss B. (1981) Extension of the transcriptional and translational map of the left end of the vaccinia virus genome to 21 kilobase pairs. J. Virol. 39, 733–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mahr A., Roberts B. E. (1984) Arrangement of late RNAs transcribed from a 7.1 kilobase Eco R1 vaccinia virus DNA fragment. J. Virol. 49, 510–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Colby C., Jurale C., Kates J. R. (1971) Mechanism of synthesis of vaccinia virus double-stranded ribonucleic acid in vivo and in vitro. J. Virol. 7, 71–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boone R. F., Parr R. P., Moss B. (1979) Intermolecular duplexes formed from polyadenylated vaccinia virus RNA. J. Virol. 30, 365–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mangone M., Manoharan A. P., Thierry-Mieg D., Thierry-Mieg J., Han T., Mackowiak S. D., Mis E., Zegar C., Gutwein M. R., Khivansara V., Attie O., Chen K., Salehi-Ashtiani K., Vidal M., Harkins T. T., Bouffard P., Suzuki Y., Sugano S., Kohara Y., Rajewsky N., Piano F., Gunsalus K. C., Kim J. K. (2010) The landscape of C. elegans 3′UTRs. Science 329, 432–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tsuchihara K., Suzuki Y., Wakaguri H., Irie T., Tanimoto K., Hashimoto S., Matsushima K., Mizushima-Sugano J., Yamashita R., Nakai K., Bentley D., Esumi H., Sugano S. (2009) Massive transcriptional start site analysis of human genes in hypoxia cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 2249–2263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Earl P. L., Cooper N., Wyatt L. S., Moss B., Carroll M. W. (2001) Preparation of cell cultures and vaccinia virus stocks. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. Chapter 16, Unit 16.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Earl P. L., Moss B., Wyatt L. S., Carroll M. W. (2001) Generation of recombinant vaccinia viruses. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. Chapter 16, Unit 16.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bailey T. L., Elkan C. (1994) Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 2, 28–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hoskins R. A., Landolin J. M., Brown J. B., Sandler J. E., Takahashi H., Lassmann T., Yu C., Booth B. W., Zhang D., Wan K. H., Yang L., Boley N., Andrews J., Kaufman T. C., Graveley B. R., Bickel P. J., Carninci P., Carlson J. W., Celniker S. E. (2011) Genome-wide analysis of promoter architecture in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Res. 21, 182–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kapranov P., Cheng J., Dike S., Nix D. A., Duttagupta R., Willingham A. T., Stadler P. F., Hertel J., Hackermüller J., Hofacker I. L., Bell I., Cheung E., Drenkow J., Dumais E., Patel S., Helt G., Ganesh M., Ghosh S., Piccolboni A., Sementchenko V., Tammana H., Gingeras T. R. (2007) RNA maps reveal new RNA classes and a possible function for pervasive transcription. Science 316, 1484–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ni T., Corcoran D. L., Rach E. A., Song S., Spana E. P., Gao Y., Ohler U., Zhu J. (2010) A paired-end sequencing strategy to map the complex landscape of transcription initiation. Nat. Methods 7, 521–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rosel J. L., Earl P. L., Weir J. P., Moss B. (1986) Conserved TAAATG sequence at the transcriptional and translational initiation sites of vaccinia virus late genes deduced by structural and functional analysis of the HindIII H genome fragment. J. Virol. 60, 436–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee-Chen G. J., Niles E. G. (1988) Map positions of the 5′ ends of eight mRNAs synthesized from the late genes in the vaccinia virus HindIII D fragment. Virology 163, 80–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Larsen B., Wills N. M., Nelson C., Atkins J. F., Gesteland R. F. (2000) Nonlinearity in genetic decoding: homologous DNA replicase genes use alternatives of transcriptional slippage or translational frameshifting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 1683–1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shinde D., Lai Y., Sun F., Arnheim N. (2003) Taq DNA polymerase slippage mutation rates measured by PCR and quasi-likelihood analysis: (CA/GT)n and (A/T)n microsatellites. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 974–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ink B. S., Pickup D. J. (1990) Vaccinia virus directs the synthesis of early mRNAs containing 5′ poly(A) sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 1536–1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ahn B. Y., Rosel J., Cole N. B., Moss B. (1992) Identification and expression of rpo19, a vaccinia virus gene encoding a 19-kiloDalton DNA-dependent RNA polymerase subunit. J. Virol. 66, 971–982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sebring E. D., Salzman N. P. (1967) Metabolic properties of early and late vaccinia messenger ribonucleic acid. J. Virol. 1, 550–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Oda K. I., Joklik W. K. (1967) Hybridization and sedimentation studies on “early” and “late” vaccinia messenger RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 27, 395–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vos J. C., Stunnenberg H. G. (1988) Derepression of a novel class of vaccinia virus genes upon DNA replication. EMBO J. 7, 3487–3492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Keck J. G., Baldick C. J., Jr., Moss B. (1990) Role of DNA replication in vaccinia virus gene expression: a naked template is required for transcription of three late transactivator genes. Cell 61, 801–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yuen L., Moss B. (1987) Oligonucleotide sequence signaling transcriptional termination of vaccinia virus early genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 6417–6421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shuman S., Moss B. (1989) Bromouridine triphosphate inhibits transcription termination and mRNA release by vaccinia virions. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 21356–21360 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Patel D. D., Ray C. A., Drucker R. P., Pickup D. J. (1988) A poxvirus-derived vector that directs high levels of expression of cloned genes in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 9431–9435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Antczak J. B., Patel D. D., Ray C. A., Ink B. S., Pickup D. J. (1992) Site-specific RNA cleavage generates the 3′ end of a poxvirus late mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 12033–12037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. D'Costa S. M., Bainbridge T. W., Condit R. C. (2008) Purification and properties of the vaccinia virus mRNA processing factor. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 5267–5275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. D'Costa S. M., Antczak J. B., Pickup D. J., Condit R. C. (2004) Post-transcription cleavage generates the 3′ end of F17R transcripts in vaccinia virus. Virology 319, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kozak M. (2002) Pushing the limits of the scanning mechanism for initiation of translation. Gene 299, 1–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shirokikh N. E., Spirin A. S. (2008) Poly(A) leader of eukaryotic mRNA bypasses the dependence of translation on initiation factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10738–10743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Xia X., MacKay V., Yao X., Wu J., Miura F., Ito T., Morris D. R. (2011) Translation initiation: a regulatory role for poly(A) tracts in front of the AUG codon in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 189, 469–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Moss B., Rosenblum E. N., Paoletti E. (1973) Polyadenylate polymerase from vaccinia virions. Nat. New Biol. 245, 59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gershon P. D., Ahn B. Y., Garfield M., Moss B. (1991) Poly(A) polymerase and a dissociable polyadenylation stimulatory factor encoded by vaccinia virus. Cell 66, 1269–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gershon P. D., Moss B. (1993) Uridylate-containing RNA sequences determine specificity for binding and polyadenylation by the catalytic subunit of vaccinia virus poly(A) polymerase. EMBO J. 12, 4705–4714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shuman S., Moss B. (1988) Factor-dependent transcription termination by vaccinia virus RNA polymerase: evidence that the cis-acting termination signal is in nascent RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 6220–6225 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shuman S., Broyles S. S., Moss B. (1987) Purification and characterization of a transcription termination factor from vaccinia virions. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 12372–12380 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gross C. H., Shuman S. (1996) Vaccinia virions lacking the RNA helicase nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase II are defective in early transcription. J. Virol. 70, 8549–8557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Paolette E., Rosemond-Hornbeak H., Moss B. (1974) Two nucleic acid-dependent nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolases from vaccinia virus: purification and characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 249, 3273–3280 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Paoletti E., Moss B. (1974) Two nucleic acid-dependent nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolases from vaccinia virus. Nucleotide substrate and polynucleotide cofactor specificities. J. Biol. Chem. 249, 3281–3286 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gross C. H., Shuman S. (1998) The nucleoside triphosphatase and helicase activities of vaccinia virus NPH-II are essential for virus replication. J. Virol. 72, 4729–4736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Taylor S. D., Solem A., Kawaoka J., Pyle A. M. (2010) The NPH-II helicase displays efficient DNA center dot RNA helicase activity and a pronounced purine sequence bias. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 11692–11703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Parsons B. L., Pickup D. J. (1990) Transcription of orthopoxvirus telomeres at late times during infection. Virology 175, 69–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Howard S. T., Ray C. A., Patel D. D., Antczak J. B., Pickup D. J. (1999) A 43-nucleotide RNA cis-acting element governs the site-specific formation of the 3′ end of a poxvirus late mRNA. Virology 255, 190–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cuperus J. T., Fahlgren N., Carrington J. C. (2011) Evolution and functional diversification of MIRNA genes. Plant Cell 23, 431–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Esteller M. (2011) Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 861–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Vogel J., Wagner E. G. (2007) Target identification of small noncoding RNAs in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10, 262–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Alcami A. (2003) Viral mimicry of cytokines, chemokines and their receptors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 36–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.