Background: The mechanism by which Tks4 regulates actin cytoskeleton is largely unknown.

Results: In response to EGF treatment, Tks4 is tyrosine-phosphorylated and associated with the EGF receptor.

Conclusion: The results provide a new mechanism of regulating cell migration.

Significance: Tks4 can be targeted in regulation of tumor cell migration.

Keywords: Cell Biology, Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR), Nonreceptor Tyrosine Kinase, Protein Phosphorylation, Signal Transduction, PX Domain, Src Tyrosine Kinase, Tks4, Cell Migration

Abstract

Mutations in the SH3PXD2B gene coding for the Tks4 protein are responsible for the autosomal recessive Frank-ter Haar syndrome. Tks4, a substrate of Src tyrosine kinase, is implicated in the regulation of podosome formation. Here, we report a novel role for Tks4 in the EGF signaling pathway. In EGF-treated cells, Tks4 is tyrosine-phosphorylated and associated with the activated EGF receptor. This association is not direct but requires the presence of Src tyrosine kinase. In addition, treatment of cells with LY294002, an inhibitor of PI 3-kinase, or mutations of the PX domain reduces tyrosine phosphorylation and membrane translocation of Tks4. Furthermore, a PX domain mutant (R43W) Tks4 carrying a reported point mutation in a Frank-ter Haar syndrome patient showed aberrant intracellular expression and reduced phosphoinositide binding. Finally, silencing of Tks4 was shown to markedly inhibit HeLa cell migration in a Boyden chamber assay in response to EGF or serum. Our results therefore reveal a new function for Tks4 in the regulation of growth factor-dependent cell migration.

Introduction

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)3 is involved in diverse cellular processes, including proliferation and motility; however, it is also implicated in the development of various human cancers (1). Binding of EGF to its receptor at the plasma membrane induces dimerization of EGFR, which results in the autophosphorylation and activation of EGFR (2) A number of signaling pathways have been identified through which EGFR may regulate rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton, such as activation of phospholipase Cγ1 (3) and Rho GTPases (4, 5). Tyrosine kinases of the Src family are also involved in transmitting signals downstream of EGFR and other receptors, and a variety of Src substrates are known to regulate actin cytoskeleton (6).

Tks5/FISH was first identified as a Src substrate possessing one phox homology (PX) domain on its N terminus and five Src homology (SH3) domains (7). Tks5 was shown to be localized at the podosomes of Src-transformed cells and associated with some members of the ADAM metalloprotease family (8). Later, Tks5 was found to be expressed in podosomes in invasive cancer cells. In addition, Tks5 expression was required for protease-driven Matrigel invasion in human cancer cells (9). In this process Nck adaptor proteins, Nck1 and Nck2, seem to link Tks5 to invadopodia actin regulation and extracellular matrix degradation (10). Finally, Tks5 has been shown to be required for migration of neural crest cell during development of zebrafish embryos (11).

Recently, a homolog of Tks5, Tks4, has been identified and shown to also influence podosomes in cells (12). Tks4 has domain architecture similar to that of Tks5, containing one PX domain and four SH3 domains (12). Tks4 was also implicated in the production of reactive oxygen species by tumor cells (13–15) and in the differentiation of white adipose tissue (16). Intriguingly, in two independent mouse models, the absence of Tks4 resulted in abnormal development causing runted growth, craniofacial and skeletal abnormalities, hearing impairment, glaucoma, and the virtual absence of white adipose tissue (17, 18). In humans, the Tks4 deficiency is responsible for the development of Frank-ter Haar syndrome (18). Recently, we have shown that Tks4 is instrumental for the development of EGF-induced membrane ruffles and lamellipodia as well as for efficient cellular attachment and spreading of HeLa cells (19). In addition, it has been demonstrated that Tks4 associates with Src tyrosine kinase and cortactin, a well established activator of the Arp2/3 complex (19).

In this study we have investigated the mechanism by which Tks4 contributes to EGF signaling. We demonstrate that Tks4 is tyrosine-phosphorylated and associated with the activated EGF receptor upon EGF stimulation of cells. This association is not direct but requires the presence of Src tyrosine kinase. In addition, the PX domain is instrumental for the proper translocation of Tks4 to membrane ruffles in EGF-treated cells. A PX domain mutant (R43W) Tks4 carrying a reported point mutation in a Frank-ter Haar syndrome patient showed aberrant intracellular expression and reduced phosphoinositide binding. Finally, silencing of Tks4 was shown to inhibit HeLa cell migration markedly in response to EGF or serum. Our results therefore reveal a new function for Tks4 in the regulation of growth factor-dependent cell migration.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies, Constructs, and Reagents

Antibodies against the EGFR (06-847) and phosphotyrosine residues (clone 4G10, 05-321) were obtained from Millipore. Antibodies against the V5 epitope (R96025 and A7345) were purchased from Invitrogen and Sigma-Aldrich, respectively. Antibodies against GST (sc-459) and Src (2109) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and Cell Signaling Technologies, respectively. Antibody against β-actin (A5316) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit (A11008) and Alexa Fluor 488 rabbit anti-mouse (A11059) antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen. Generation of polyclonal anti-Tks4 antibody was described earlier (19). The V5 epitope-tagged Tks4 and PX domain of Tks4 expressed as GST fusion protein were described previously (19). V5-Tks4Y25F,Y373F,Y508F, V5-Tks4R71L,R94L, V5-Tks4R43Q, V5-Tks4R43W, as well as GST-PXR43W mutants were generated using the QuikChange Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). cDNA of full-length Src in mammalian expression vector pCMV6 was purchased from OriGene Technologies, Inc. Chicken ΔSH2 Src and ΔSH3 Src constructs subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pSGT were obtained from the laboratory of Giulio Superti-Furga (Vienna, Austria). Stock solutions of EGF (Sigma-Aldrich), PP1 (Biomol), and LY294002 (Merck) were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell Lines, Transfection, and Stimulation

A431, COS-7, and HeLa cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen), penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (50 μg/ml). All cell lines were transiently transfected with Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For stimulation, cells were serum-starved overnight and stimulated with EGF at 50 ng/ml for 10 min. Alternatively, cells were pretreated with the PI 3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 at 20 μm or the Src inhibitor PP1 at 20 μm for 60 min and then stimulated with EGF as above.

Chemoinvasion Assay

Boyden chamber invasion assays were carried out on HeLa cells 48 h after Stealth siRNA transfection. The Millipore QCM Cell Migration Assay (ECM508) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions with the modification that the membrane surface of each chamber was coated with 10 μg of collagen type I (Sigma-Aldrich, C8919) for 1 h in a 37 °C incubator, washed briefly in PBS, and air-dried. 1.5 × 105 cells in DMEM were added to the upper chamber and allowed to penetrate the porous membrane (8 μm) to the bottom chamber containing EGF (100 ng/ml) or 10% FBS. Cells on the top surface of the membrane were removed after 24-h incubation, and the cells on the bottom surface were quantified.

Confocal Microscopy

COS-7 cells plated on glass coverslips were transiently transfected with different Tks4 constructs as indicated and then serum-starved overnight. Cells were pretreated with 20 μm LY294002 for 60 min and then treated with 50 ng/ml EGF for 10 min. After treatment cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS for 15 min, permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, and blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 20 min. Anti-Tks4 rabbit serum was applied in 1:1,000 dilution for 30 min. After washing with PBS the samples were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-mouse secondary antibody or anti-rabbit antibody (for staining endogenous Tks4) for 30 min. After 40 min of washing with PBS, coverslips were mounted onto slides in a 100 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.5, containing 10% Mowiol 4-88 (Calbiochem), 25% glycerol, and 2.5% 1,4-diazobicyclo-[2.2.2]octane (DABCO, Sigma-Aldrich). Tks4 membrane localization was quantified by counting at least 100 cells/sample. Microscopy was performed on a Nikon Eclipse E400 fluorescence microscope or Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope.

Lipid Binding Assay

PIP strips membranes were obtained from Invitrogen (P23750). Protein-lipid overlay experiments were performed using GST-PX (amino acids 1–130) and GST-PXR43W fusion proteins following the manufacturer's protocol.

siRNA Transfection and siRNA-resistant Mutant of Tks4

Silencing of Tks4 was achieved by transfecting HeLa cells (50% confluent) with specific stealth siRNA duplex (GCCUGAUACCAAUUGAUGAAUACUG) or nontargeting (GCCGGAUACCAAUUGAUUAACAUUG) stealth siRNA duplex in a final concentration of 40 nm using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Reagent (Invitrogen). Two days after transfection, the cells were used for experiments, and the knockdown was verified by Western blotting of equal protein amounts of lysates from control and Tks4-silenced cells. To rescue the phenotype of Tks4 siRNA, an siRNA-resistant mutant of V5-Tks4 was created by substituting five nucleotides in the Tks4 siRNA targeting region (GCCTGATCCCCATCGATGAGTATTG).

Statistics

All quantitative results are presented as the mean ± S.D. of (at least three) independent experiments. Statistical differences between two groups of data were analyzed by Student's t test.

RESULTS

EGF Induces Tyrosine Phosphorylation of Tks4 and Its Interaction with the EGFR

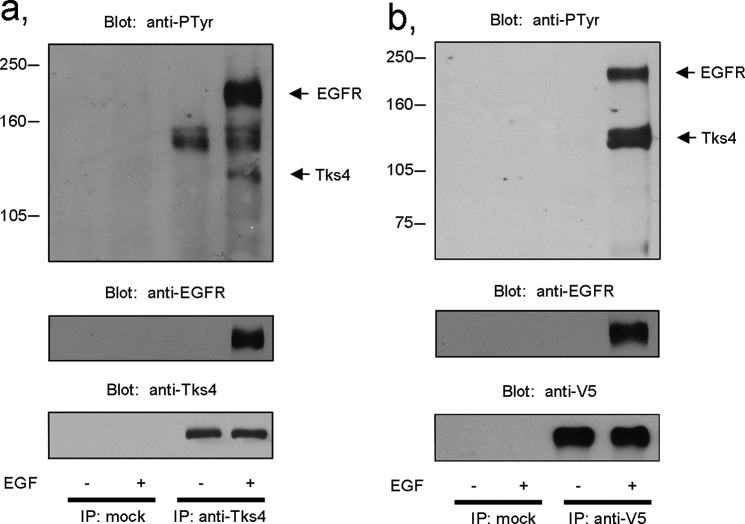

We have investigated whether Tks4 is involved directly in the EGF signaling pathway. Serum-starved A431 cells were stimulated with EGF for 10 min or left untreated, and then endogenous Tks4 was immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal anti-Tks4 antibody. As seen in Fig. 1a, Tks4 is subject of tyrosine phosphorylation in response to EGF stimulation. In addition, the activated EGFR was co-immunoprecipitated with the scaffold protein. Interestingly, a 150-kDa phosphotyrosine protein was also consistently observed in the immunoprecipitates, although the association of this unknown protein seemed to be independent of growth factor treatment. To confirm the involvement of Tks4 in the EGF signaling pathway in another cell system, V5 epitope-tagged Tks4 was transiently overexpressed in COS-7 cells, then after EGF stimulation Tks4 was immunoprecipitated with an anti-V5 antibody. Fig. 1b demonstrates that in this system Tks4 is also tyrosine-phosphorylated upon EGF treatment and associates with the autophosphorylated EGFR. These results establish a novel interaction between Tks4 and the EGFR, implicating Tks4 in growth factor signaling pathways.

FIGURE 1.

Tks4 is tyrosine-phosphorylated and associated with the EGFR upon EGF treatment of cells. a, serum-starved A431 cells were stimulated with EGF (50 ng/ml) for 10 min, and then endogenous Tks4 was immunoprecipitated (IP) with a polyclonal anti-Tks4 antibody. After SDS-PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose, samples were analyzed by anti-phosphotyrosine, anti-EGFR, and anti-Tks4 antibodies. b, wild-type, V5 epitope-tagged Tks4 was transiently expressed in COS-7 cells, and then serum-starved cells were stimulated with EGF or left untreated. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-V5 antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-phosphotyrosine, anti-EGFR, and anti-V5 antibodies. These results are representative of three experiments.

Src Is Required for EGF-dependent Tks4 Phosphorylation

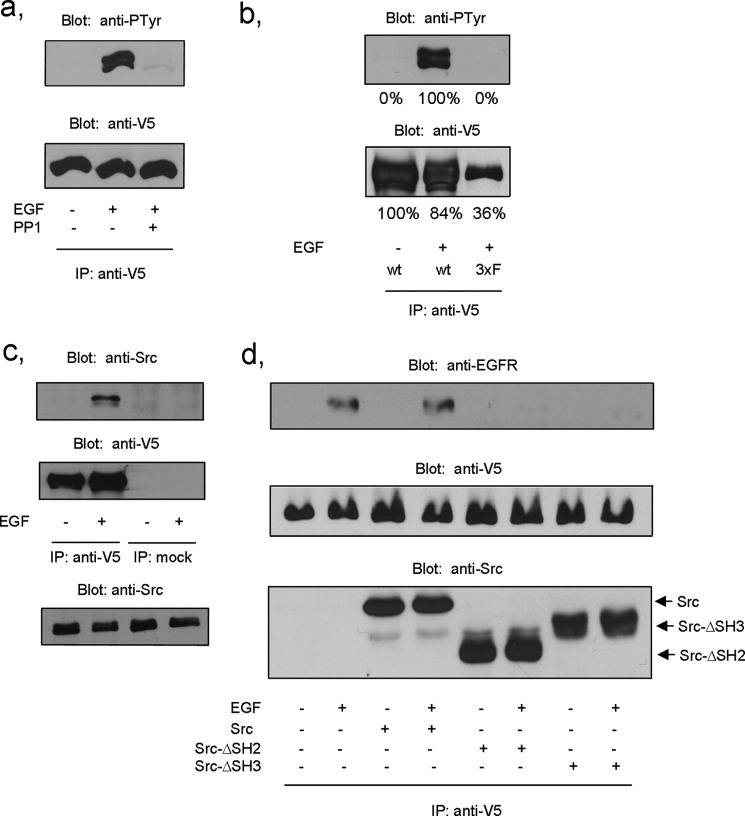

Considering the structure of Tks4, it seemed unlikely that it could associate directly with the tyrosine kinase receptor. Because both Tks4 and its close kin Tks5 are prominent substrates of the Src tyrosine kinase implicated in podosome formation (7–9, 12), we proposed that Src might function as a linker between Tks4 and the EGFR as described for many other protein complexes (20). To challenge our hypothesis, first, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with V5-Tks4 construct and then pretreated with PP1, a specific inhibitor of Src. Following EGF treatment V5-Tks4 was immunoprecipitated and subjected to anti-phosphotyrosine immunoblotting. The inhibitor markedly decreased tyrosine phosphorylation of Tks4 (Fig. 2a). A previous study has shown that Src kinase phosphorylates Tks4 on three tyrosine residues (12). Therefore, we introduced point mutations into Tks4, changing tyrosines 25, 373, and 508 to phenylalanines, respectively. V5-Tks4Y25F,Y373F,Y508F was transiently expressed in COS-7 cells, then after serum starvation cells were treated with EGF. Tks4 was immunoprecipitated from lysates with anti-V5 antibody. The anti-phosphotyrosine immunoblot demonstrated that phosphorylation of the triple mutant protein is significantly decreased upon EGF treatment (Fig. 2b). It is worth noting that the expression level of the triple Tks4 mutant is somewhat reduced compared with that of the wild type, nevertheless it is clearly not able to be phosphorylated, as indicated by the densitometry of the appropriate bands (Fig. 2b). Next, we examined whether Src tyrosine kinase could associate with Tks4. To this end, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with V5-Tks4 construct and then stimulated with EGF or left untreated. Tks4 proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-V5 antibody and subjected to anti-Src immunoblotting. Fig. 2c demonstrates that EGF treatment of the cells induced the association of Tks4 with Src. To prove that Src functions as an adaptor molecule linking EGFR to Tks4, wild-type Src and Src mutants lacking either the SH2 (ΔSH2 Src) or the SH3 (ΔSH3 Src) domains were co-expressed with V5-Tks4 in COS-7 cells. As Fig. 2d demonstrates, expression of either ΔSH2 Src or ΔSH3 Src inhibited the association of Tks4 with EGFR, whereas expression of wild-type Src did not interfere with the interaction. We have to note that when overexpressed all Src constructs seem to be co-immunoprecipitated with Tks4 independent of cell stimulation. These results collectively suggest that Src kinase serves as a linker between the receptor and the scaffold protein and is responsible for Tks4 phosphorylation in response to EGF stimulation.

FIGURE 2.

Src tyrosine kinase interacts with and phosphorylates Tks4 in response to EGF stimulation. a, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with V5-Tks4 construct, and after overnight serum starvation cells were stimulated with EGF or left untreated. Prior to stimulation the cells were treated with the Src kinase inhibitor PP1. Tks4 was immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-V5 antibody and subjected to anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-V5 immunoblots. b, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with wild-type V5-Tks4 or triple phosphorylation mutant (3xF) V5-Tks4Y25F,Y373F,Y508F constructs. Lysates of serum-starved cells were then subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-V5 antibody. Bound proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-V5 antibodies. Results of densitometry of the corresponding bands are also indicated. c, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with V5-Tks4. Serum-starved cells were treated with EGF, and Tks4 was immunoprecipitated with anti-V5 antibody. Immunoprecipitates were then immunoblotted with anti-Src and V5 antibodies. Immunoblot of lysates used in this experiment shows expression levels of Src (bottom panel). These results are typical of at least three experiments. d, wild-type Src and Src mutants lacking either the SH2 (ΔSH2 Src) or the SH3 (ΔSH3 Src) domains were co-expressed with V5-Tks4 in COS-7 cells. Serum-starved cells were challenged with EGF for 10 min or left untreated. Tks4 was then immunoprecipitated from cell lysates, and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by anti-EGFR, anti-V5, and anti-Src antibodies.

PX Domain Is Instrumental for Tks4 Function

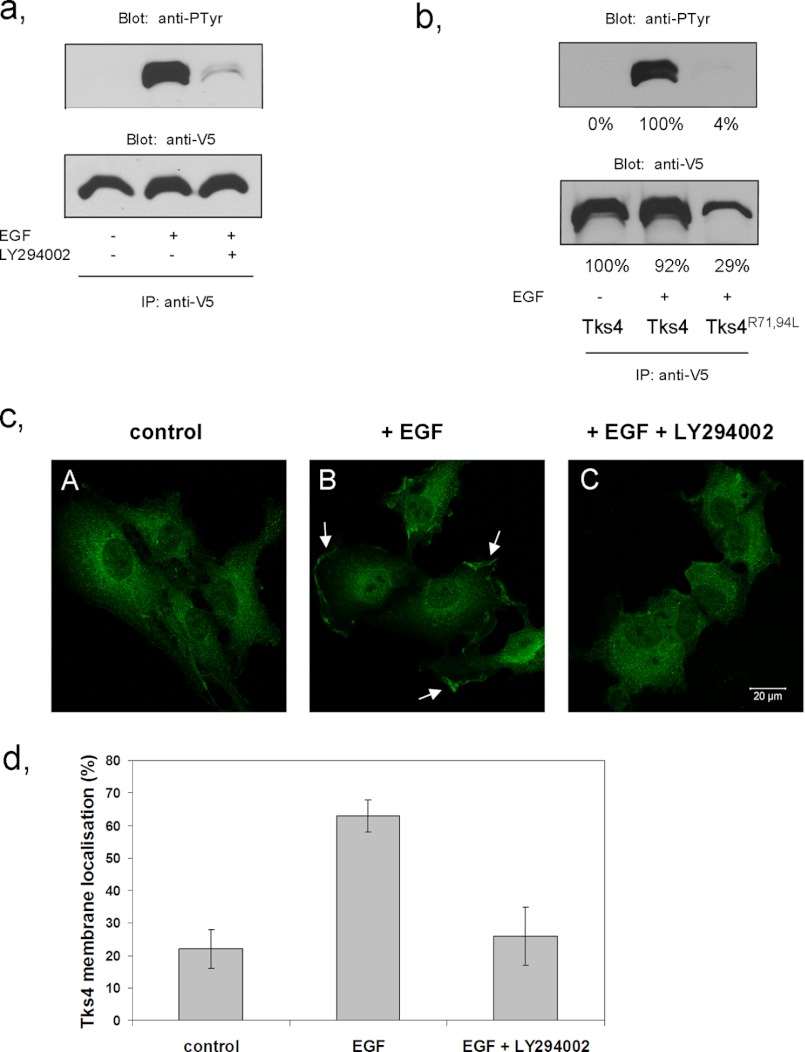

The family of Tks proteins possesses a PX domain that can bind specific membrane lipids and is implicated in the appropriate cellular localization of Tks4 and Tks5 (7–9, 12). Therefore, we asked whether the PX domain is required for tyrosine phosphorylation and proper subcellular localization of Tks4. First, V5 epitope-tagged wild-type Tks4 was transiently expressed in COS-7 cells, and then cells expressing V5-Tks4 were stimulated with EGF or left untreated. As shown in Fig. 3a, EGF-dependent phosphorylation of the scaffold protein could be inhibited by addition of the specific PI 3-kinase inhibitor LY294002. To confirm that the intact PX domain is instrumental for the adequate tyrosine phosphorylation, point mutations were introduced into the PX domain of Tks4 changing the conserved arginines 71 and 94 to leucines, as described earlier for other PX domains (21–23). Fig. 3b demonstrates that the mutations introduced reduced the tyrosine phosphorylation of Tks4 despite the fact that the expression level of the mutant Tks4 in COS-7 cells was somewhat lower. To examine the roles of PX domain in the function of Tks4 further, subcellular rearrangement of endogenous Tks4 was studied using immunofluorescence microscopy. In quiescent COS-7 cells, Tks4 showed a uniform cytoplasmic distribution, with membrane localization in only a low proportion of cells (approximately 20%). In response to EGF, Tks4 was seen to be translocated to membrane ruffles in ∼60% of cells (Fig. 3, c and d). However, when cells were pretreated with LY294002, membrane translocation of Tks4 was strongly inhibited. These findings suggest that the functional PX domain as well as the activation of PI 3-kinase is important for the proper EGF-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation and membrane localization of Tks4.

FIGURE 3.

EGF induces PI 3-kinase-dependent plasma membrane translocation of Tks4. a, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with V5-Tks4 and after serum-starvation cells were stimulated with EGF or left untreated. Prior to stimulation the cells were treated with the PI 3-kinase inhibitor LY294002. Tks4 proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-V5 antibody and subjected to anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-V5 immunoblotting. b, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with wild-type V5-Tks4 and V5-Tks4R71L,R94L constructs and challenged with EGF. Cell lysates were then subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-V5 antibody. Bound proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-V5 antibodies. Results of densitometry of the corresponding bands are also indicated. c, serum-starved COS-7 cells were stimulated with EGF (B) or left untreated (A). Prior to stimulation with EGF, cells were treated with the PI 3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 (C). Cells were then fixed and processed for immunofluorescence. Endogenous expression and subcellular localization of Tks4 were detected using a Tks4-specific polyclonal antibody. Arrows indicate Tks4 present at the plasma membrane. The scale bar represents 20 μm. d, percentage of cells with Tks4-immunreactivity in membrane ruffles under serum-starved condition or after EGF or EGF+LY294002 treatments was quantified by an observer who was blinded to cell treatment status (n = 100 cells for each group per experiment). Error bars, ±S.D.

The PX Domain Mutant of Tks4 Is Unstable Intracellularly

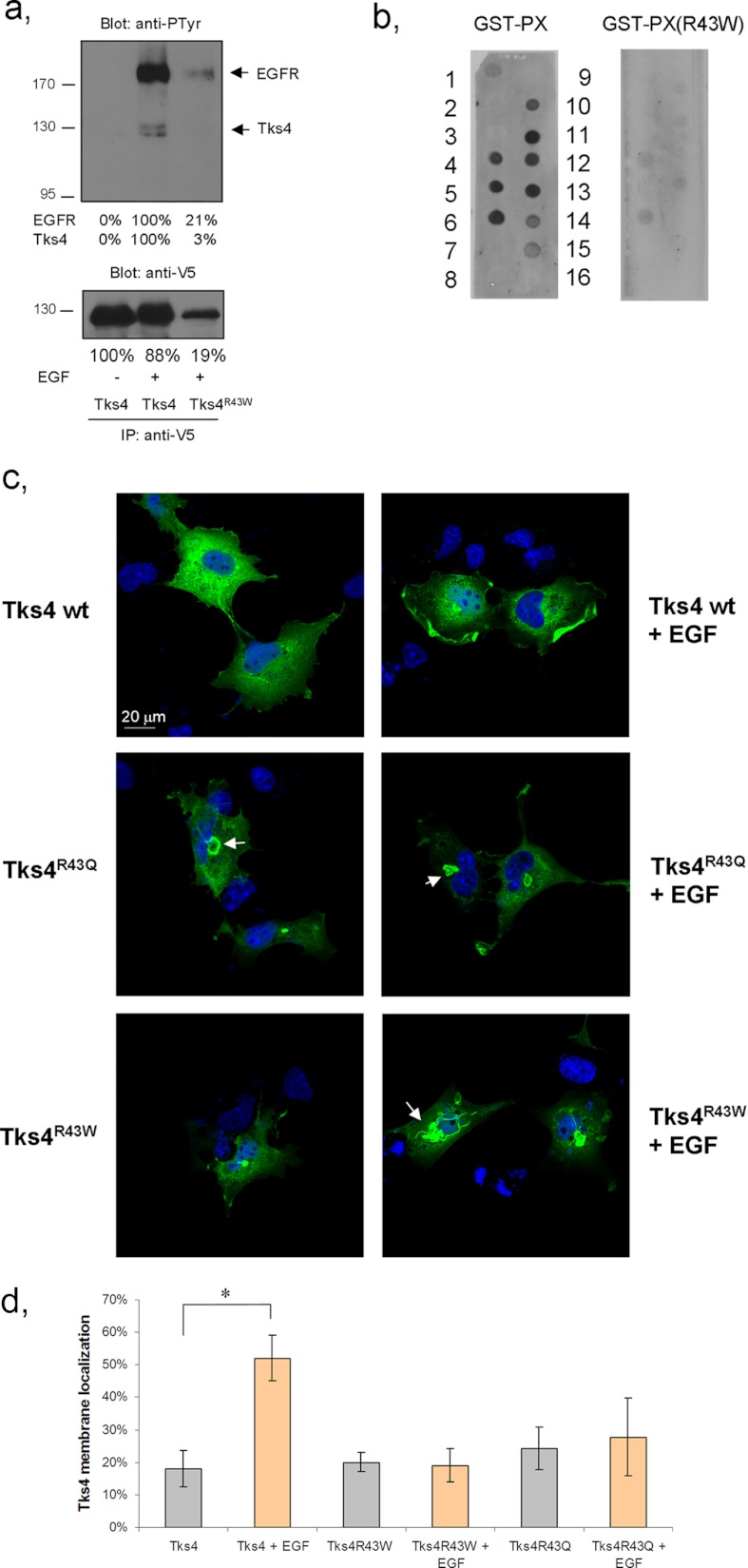

Very recently, Iqbal et al. identified a family with Frank-ter Haar syndrome whose Tks4 gene (SH3PXD2B) contains a substitution mutation which results in the change of the conserved arginine 43 to tryptophan in the PX domain (18). This mutation was predicted to abolish binding to phospholipids (18). We were interested to discover whether the above mutation really impaired the expression and/or the function of the protein. The R43W mutant of V5 epitope-tagged Tks4 was therefore generated and expressed in COS-7 cells. As shown in Fig. 4a, the expression level of the mutant protein was significantly decreased compared with the wild-type form. Intriguingly, upon EGF treatment, despite the low expression the mutant protein was capable of associating with the EGFR. It has been well established that the PX domain is required for lipid binding (24–26). To test directly whether the R43W mutation functionally inactivates the PX domain, both wild-type and R43W PX domains were expressed as GST fusion proteins and examined in a protein-lipid overlay assay, as described earlier (19). Fig. 4b demonstrates that whereas the wild-type PX domain could bind to a selection of different phosphoinositides, the R43W mutant was practically unable to recognize any of those lipids. We have to note that a weak interaction of the wild-type PX domain was detected with phosphatidylserine, which was not seen in our previous work (19). Finally, we analyzed the intracellular localization of mutant Tks4 proteins. In a previous study we showed that Tks4R43Q mutant is able to be recruited to membrane ruffles induced by EGF (19). However, quantification of subcellular localization of this mutant protein was not performed. To compare the subcellular localization of the mutant Tks4 proteins in the same cell type, both Tks4R43Q and Tks4R43W were transiently expressed in COS-7 cells stimulated with EGF or left untreated. As shown in Fig. 4, c and d, membrane localization of both mutants was detected in ∼20% of the cells. However, in contrast to wild-type Tks4, the mutant proteins were not capable of translocating to membrane ruffles induced by EGF. Intriguingly, when mutant Tks4 proteins were expressed in cells both proteins formed aggregates and accumulated around the nucleus. It has been documented that misfolded and aggregated proteins could be sequestered into specialized structures named aggresomes (27, 28). Therefore, it is very likely that both Tks4 mutants are unstable intracellularly and sequestered into aggresomes. Taken together, our data suggest that the R43W mutation found in Frank-ter Haar syndrome seriously impairs the folding and the function of Tks4 leading to accelerated degradation of the protein.

FIGURE 4.

Tks4R43W mutant shows aberrant intracellular expression and reduced phosphoinositide binding. a, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with wild-type V5-Tks4 or V5-Tks4R43W constructs and challenged with EGF. Cell lysates were then subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-V5 antibody. Bound proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-V5 antibodies. Results of densitometry of the corresponding bands are also indicated. b, the lipid-binding ability of GST-PX (left) and GST-PX carrying a mutation (R43W, right) of Tks4 was tested in protein-lipid overlay assay. Layout of the PIP strip was the following: 1, lysophosphatidic acid; 2, lysophosphatidylcholine; 3, phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns); 4, PtdIns(3)P; 5, PtdIns(4)P; 6, PtdIns(5)P; 7, phosphatidylethanolamine; 8, phosphatidylcholine; 9, sphingosine 1-phosphate; 10, PtdIns(3,4)P2; 11, PtdIns(3,5)P2; 12, PtdIns(4,5)P2; 13, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3; 14, phosphatidic acid; 15, phosphatidylserine; 16, blank. c, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with V5-Tks4, V5-Tks4R43Q, or V5-Tks4R43W. After 48 h, cells were fixed and stained for Tks4 with anti-V5 antibody. Cell nuclei were visualized by DAPI staining. Arrows indicate Tks4 aggregates close to the nucleus. The scale bar represents 20 μm. d, the percentage of cells with Tks4 immunoreactivity in membrane ruffles under serum-starved condition or after EGF treatment was quantified by an observer who was blinded to cell treatment status (n = 100 cells for each group per experiment). Asterisk indicates p < 0.005. Error bars, ±S.D.

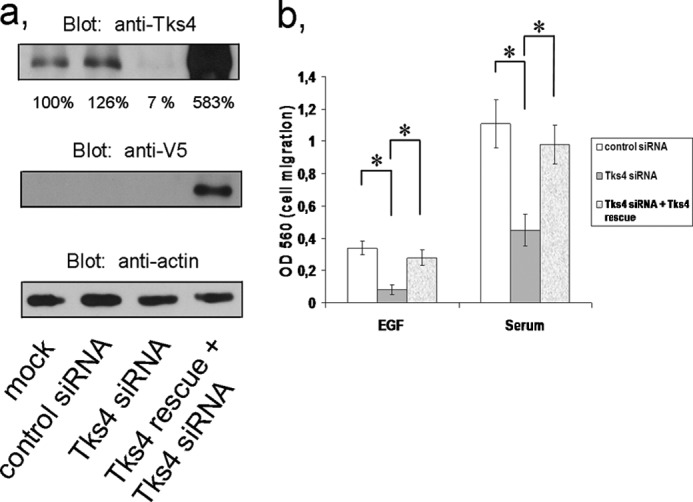

Tks4 Is Required for EGF-dependent Cell Migration in HeLa Cells

We have reported recently that Tks4 could associate with cortactin, an important protein implicated in cell migration (29, 30), and regulate cell spreading (19). This raised the intriguing possibility that Tks4 might contribute to EGF-dependent cell migration. To analyze the role of Tks4 in cell migration, Tks4 was knocked down in HeLa cells by means of RNA interference, which resulted in a considerable degree of reduction of the protein level (Fig. 5a). Cells were then serum-starved and placed in Boyden chambers to perform the chemoinvasion assay according to the manufacturer's instructions. After challenging the cells with EGF or fetal calf serum, cell migration was quantified. As seen in Fig. 5b, although EGF induced detectable cell migration, the effect of serum, possibly due to the number of growth factors present, was more prominent. Silencing of Tks4 in HeLa cells resulted in a remarkable inhibition of cell migration in both EGF- and serum-treated cells. To confirm that the inhibitory effect of Tks4 was specifically due to Tks4 silencing rather then to stress responses or other off-target effects Tks4 siRNA-expressing cells were transfected with a Tks4 “rescue” expression plasmid mutated within the siRNA-targeted sequence (Fig. 5a). Expression of the mutant Tks4 cDNA restored the ability of EGF or serum to induce cell migration (Fig. 5b).

FIGURE 5.

Tks4 silencing inhibits EGF- and serum-dependent cell migration. a, HeLa cells were transfected with control and Tks4-specific stealth siRNA duplexes as well as with siRNA-resistant V5-Tks4 (Tks4 rescue) constructs. 48 h later cells were harvested, and lysates were immunoblotted with anti-Tks4 antibody. Actin was used as a loading control for cell lysates. Results of densitometry of the corresponding bands are also indicated. b, HeLa cells were transfected with control, Tks4-specific stealth siRNA duplexes, and Tks4-specific siRNA duplexes together with a siRNA-resistant Tks4 construct (Tks4 rescue). Cells were then harvested and tested using a modified Boyden chamber assay as described under “Experimental Procedures.” After 24 h, migrated cells were quantified according to the manufacturer's protocol. Error bars represent the S.E. of three independent experiments. Asterisk indicates p < 0.005.

DISCUSSION

In this paper we report a novel role for Tks4 in the EGF signaling pathway. In our previous work we showed that Tks4 was instrumental for lamellipodium and membrane ruffle formation upon EGF stimulation as well as efficient cellular attachment and spreading of HeLa cells. In addition, we have demonstrated that Tks4/HOFI could associate with cortactin, an important protein implicated in cell migration (19). Here we completed our investigation and established that Tks4 protein forms a complex with the EGFR and becomes tyrosine-phosphorylated upon EGF stimulation. Tks4 does not contain any typical phosphotyrosine binding domain (e.g. SH2 or PTB domains), and EGFR does not possess any typical proline-rich sequences suitable for interaction with any of the SH3 domains of Tks4 (see Uniprot Web site), therefore it is highly likely that the interaction between the two proteins is indirect. Furthermore, when we used EGFR purified from A431 cells for an in vitro kinase assay, as described previously (31), we could not detect EGFR-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of Tks4 and also could not observe any direct interaction between EGFR and Tks4 (data not shown). On the other hand, upon EGF treatment of COS-7 cells inducible interaction between Src tyrosine kinase and Tks4 was seen. Because the interaction of Src kinase with the EGFR has been well established (20), we propose that Src serves as an adaptor molecule which bridges between the EGFR and Tks4. This model is further supported by our several experiments in which the crucial role of Src kinase in the tyrosine phosphorylation of Tks4 upon EGF treatment was underlined: (i) the specific Src kinase inhibitor PP1 prevented Tks4 phosphorylation; (ii) the triple phosphorylation mutant of Tks4, based on the phosphorylation sites of Src on Tks4 (12), was not capable of tyrosine phosphorylation in response to EGF; (iii) finally, expression of either ΔSH2 Src or ΔSH3 Src inhibited the association of Tks4 with EGFR. These results collectively demonstrate that Tks4 is implicated in the EGF signaling pathway by forming a complex with the EGFR. The interaction of the receptor and the scaffold protein is not direct; Src tyrosine kinase may serve as a bridging adaptor. In addition, upon EGF treatment Src kinase can phosphorylate Tks4 on three tyrosine residues; the importance of this phosphorylation is not yet clear.

Protein-lipid interaction is a well underlined mechanism by which eukaryotic cells regulate membrane recruitment and activation of proteins (26). The family of Tks proteins possesses a PX domain that can bind specific membrane lipids and is implicated in the appropriate cellular localization of Tks4 and Tks5 (7–9, 12). The PX domain of both Tks4 and Tks5 shows a very similar binding affinity, the preferred lipids are the lipid products of the PI 3-kinase (12). Here we show that the PX domain is instrumental for Tks4 to participate properly in the EGF signaling pathway. Point mutations were introduced into the PX domain of Tks4 changing the conserved arginines 71 and 94 to leucines, as described earlier for other PX domains (21–23). Intriguingly, this mutant was not able to be phosphorylated on tyrosine residues upon EGF treatment. Moreover, when cells were pretreated with the specific inhibitor of PI 3-kinase, LY294002, EGF-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of Tks4 was also markedly inhibited. When subcellular localization of endogenous Tks4 was monitored by confocal microscopy in EGF-treated cells, a significant portion of Tks4 was seen to be translocated from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane. This effect was prevented by addition of PI 3-kinase inhibitor LY294002. Based on our findings the following model could be proposed: in quiescent cells Tks4 is predominantly localized in the cytoplasm. EGF stimulation through EGFR activates Src tyrosine kinase (20) which recruits Tks4 to the plasma membrane and phosphorylates it on three tyrosine residues. Interestingly, for proper membrane localization Tks4 requires its PX domain which can bind to the lipid products of PI 3-kinase (Fig. 6). It is not unique that a regulatory protein requires two independent sites for membrane translocation. For example, the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Sos is recruited to the membrane through interactions with the SH3 domains of adaptor protein Grb2, whereas its PH domain binds certain phospholipids, such as lipid products of PI 3-kinase or phosphatidic acid (32, 33).

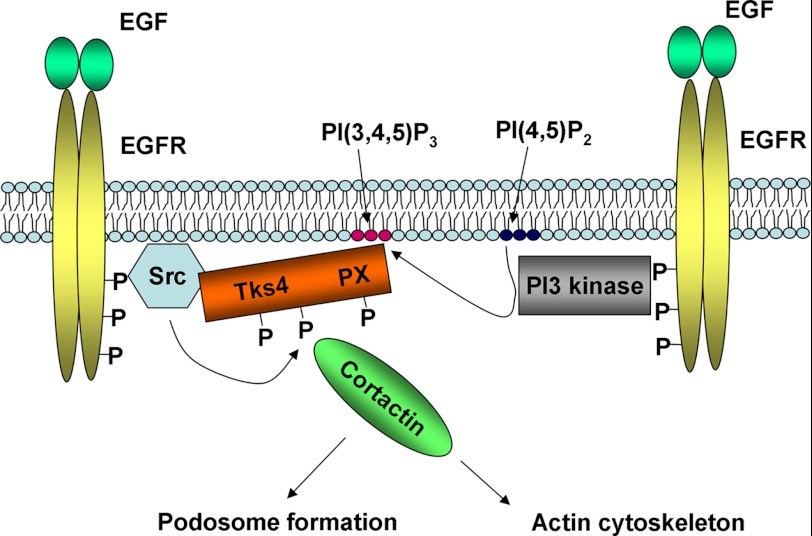

FIGURE 6.

Proposed model of Tks4 activation upon EGF stimulation. In quiescent cells, Tks4 is basically present in the cytoplasm. In response to growth factor treatment, Tks4 is translocated to the plasma membrane through at least two independent sites: an Src binding site and its lipid binding PX domain. The Tks4 PX domain may recognize lipid products of PI 3-kinase in the membrane. At the plasma membrane, Tks4 is tyrosine-phosphorylated by Src kinase. The role of Tks4 tyrosine phosphorylation is currently not known. Finally, Tks4 may signal toward podosome formation or the actin cytoskeleton. One of the known binding partners of Tks4 is cortactin, an important activator of the Arp2/3 complex.

Our data show that Tks4 is involved in the regulation of cell migration. Silencing of Tks4 in HeLa cells resulted in a remarkable inhibition of cell migration in both EGF- and serum-treated cells. This finding is in agreement with the previously suggested role of Tks4 in the remodeling of actin cytoskeleton, such as cell spreading (19). However, currently it is not clear how membrane-bound and tyrosine-phosphorylated Tks4 regulates actin polymerization leading to membrane ruffle formation or cell migration. One possible downstream candidate is cortactin, which interacts with Tks4 via its SH3 domain (19). Cortactin is a well established activator of the Arp2/3 complex which is the key regulator of the branch-chained actin polymerization (29, 34, 35). Interestingly, in addition to Tks4 and Tks5 scaffold proteins, cortactin is also implicated in the regulation of podosome formation (36). Therefore, it is likely that cortactin recruited to the membrane via Tks4 may contribute either to the formation of branched chain actin polymerization or to the development of podosomes. However, further experiments will be required to clarify how Tks proteins, in concert with cortactin, regulate the actin cytoskeleton.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Szüts (Institute of Enzymology, Research Center for Natural Sciences, Hungarian Academy of Sciences) for careful reading of the manuscript and Giulio Superti-Furga (Vienna, Austria) for providing the Src mutants.

This work was supported by Hungarian Research Fund OTKA Grants K 83867 and K 81676 and by the “Lendület” grants from the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (to L. B. and M. G.), by the Social Reform Operative Program (TÁMOP) 4.2.1/B-09/1/KONV/ 2010-007 Project (to A. L.), and by the New Hungary Development Plan, co-financed by the European Social Fund.

- EGFR

- EGF receptor

- PX

- phox homology

- SH3

- Src homology 3.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hynes N. E., Lane H. A. (2005) ERBB receptors and cancer: the complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 341–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schlessinger J., Ullrich A. (1992) Growth factor signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Neuron 9, 383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Diakonova M., Payrastre B., van Velzen A. G., Hage W. J., van Bergen en Henegouwen P. M., Boonstra J., Cremers F. F., Humbel B. M. (1995) Epidermal growth factor induces rapid and transient association of phospholipase C-γ1 with EGF-receptor and filamentous actin at membrane ruffles of A431 cells. J. Cell Sci. 108, 2499–2509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ridley A. J., Paterson H. F., Johnston C. L., Diekmann D., Hall A. (1992) The small GTP-binding protein Rac regulates growth factor-induced membrane ruffling. Cell 70, 401–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tamás P., Solti Z., Bauer P., Illés A., Sipeki S., Bauer A., Faragó A., Downward J., Buday L. (2003) Mechanism of epidermal growth factor regulation of Vav2, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rac. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 5163–5171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frame M. C., Fincham V. J., Carragher N. O., Wyke J. A. (2002) v-Src's hold over actin and cell adhesions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 233–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lock P., Abram C. L., Gibson T., Courtneidge S. A. (1998) A new method for isolating tyrosine kinase substrates used to identify FISH, an SH3 and PX domain-containing protein, and Src substrate. EMBO J. 17, 4346–4357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abram C. L., Seals D. F., Pass I., Salinsky D., Maurer L., Roth T. M., Courtneidge S. A. (2003) The adaptor protein FISH associates with members of the ADAMs family and localizes to podosomes of Src-transformed cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 16844–16851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Seals D. F., Azucena E. F., Jr., Pass I., Tesfay L., Gordon R., Woodrow M., Resau J. H., Courtneidge S. A. (2005) The adaptor protein Tks5/FISH is required for podosome formation and function, and for the protease-driven invasion of cancer cells. Cancer Cell 7, 155–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stylli S. S., Stacey T. T., Verhagen A. M., Xu S. S., Pass I., Courtneidge S. A., Lock P. (2009) Nck adaptor proteins link Tks5 to invadopodia actin regulation and ECM degradation. J. Cell Sci. 122, 2727–2740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murphy D. A., Diaz B., Bromann P. A., Tsai J. H., Kawakami Y., Maurer J., Stewart R. A., Izpisúa-Belmonte J. C., Courtneidge S. A. (2011) A Src-Tks5 pathway is required for neural crest cell migration during embryonic development. PloS One 6, e22499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buschman M. D., Bromann P. A., Cejudo-Martin P., Wen F., Pass I., Courtneidge S. A. (2009) The novel adaptor protein Tks4 (SH3PXD2B) is required for functional podosome formation. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1302–1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gianni D., Diaz B., Taulet N., Fowler B., Courtneidge S. A., Bokoch G. M. (2009) Novel p47(phox)-related organizers regulate localized NADPH oxidase 1 (Nox1) activity. Sci. Signal. 2, ra54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gianni D., Taulet N., DerMardirossian C., Bokoch G. M. (2010) c-Src-mediated phosphorylation of NoxA1 and Tks4 induces the reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent formation of functional invadopodia in human colon cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 4287–4298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gianni D., DerMardirossian C., Bokoch G. M. (2011) Direct interaction between Tks proteins and the N-terminal proline-rich region (PRR) of NoxA1 mediates Nox1-dependent ROS generation. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 90, 164–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hishida T., Eguchi T., Osada S., Nishizuka M., Imagawa M. (2008) A novel gene, fad49, plays a crucial role in the immediate early stage of adipocyte differentiation via involvement in mitotic clonal expansion. FEBS J. 275, 5576–5588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mao M., Thedens D. R., Chang B., Harris B. S., Zheng Q. Y., Johnson K. R., Donahue L. R., Anderson M. G. (2009) The podosomal-adaptor protein SH3PXD2B is essential for normal postnatal development. Mamm. Genome 20, 462–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iqbal Z., Cejudo-Martin P., de Brouwer A., van der Zwaag B., Ruiz-Lozano P., Scimia M. C., Lindsey J. D., Weinreb R., Albrecht B., Megarbane A., Alanay Y., Ben-Neriah Z., Amenduni M., Artuso R., Veltman J. A., van Beusekom E., Oudakker A., Millán J. L., Hennekam R., Hamel B., Courtneidge S. A., van Bokhoven H. (2010) Disruption of the podosome adaptor protein TKS4 (SH3PXD2B) causes the skeletal dysplasia, eye, and cardiac abnormalities of Frank-ter Haar Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 86, 254–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lányi Á., Baráth M., Péterfi Z., Bogel G., Orient A., Simon T., Petrovszki E., Kis-Tóth K., Sirokmány G., Rajnavölgyi É., Terhorst C., Buday L., Geiszt M. (2011) The homolog of the five SH3-domain protein (HOFI/SH3PXD2B) regulates lamellipodia formation and cell spreading. PloS One 6, e23653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Belsches A. P., Haskell M. D., Parsons S. J. (1997) Role of c-Src tyrosine kinase in EGF-induced mitogenesis. Front. Biosci. 2, d501–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kanai F., Liu H., Field S. J., Akbary H., Matsuo T., Brown G. E., Cantley L. C., Yaffe M. B. (2001) The PX domains of p47phox and p40phox bind to lipid products of PI(3)K. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 675–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xu Y., Hortsman H., Seet L., Wong S. H., Hong W. (2001) SNX3 regulates endosomal function through its PX-domain-mediated interaction with PtdIns(3)P. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 658–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cheever M. L., Sato T. K., de Beer T., Kutateladze T. G., Emr S. D., Overduin M. (2001) Phox domain interaction with PtdIns(3)P targets the Vam7 t-SNARE to vacuole membranes. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 613–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sato T. K., Overduin M., Emr S. D. (2001) Location, location, location: membrane targeting directed by PX domains. Science 294, 1881–1885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ellson C. D., Andrews S., Stephens L. R., Hawkins P. T. (2002) The PX domain: a new phosphoinositide-binding module. J. Cell Sci. 115, 1099–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Seet L. F., Hong W. (2006) The Phox (PX) domain proteins and membrane traffic. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 878–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johnston J. A., Ward C. L., Kopito R. R. (1998) Aggresomes: a cellular response to misfolded proteins. J. Cell Biol. 143, 1883–1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Garcia-Mata R., Gao Y. S., Sztul E. (2002) Hassles with taking out the garbage: aggravating aggresomes. Traffic 3, 388–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Buday L., Downward J. (2007) Roles of cortactin in tumor pathogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1775, 263–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clark E. S., Weaver A. M. (2008) A new role for cortactin in invadopodia: regulation of protease secretion. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 87, 581–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buday L., Downward J. (1993) Epidermal growth factor regulates p21ras through the formation of a complex of receptor, Grb2 adapter protein, and Sos nucleotide exchange factor. Cell 73, 611–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Buday L., Downward J. (2008) Many faces of Ras activation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1786, 178–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhao C., Du G., Skowronek K., Frohman M. A., Bar-Sagi D. (2007) Phospholipase D2-generated phosphatidic acid couples EGFR stimulation to Ras activation by Sos. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 706–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Uruno T., Liu J., Zhang P., Fan Y. x., Egile C., Li R., Mueller S. C., Zhan X. (2001) Activation of Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin polymerization by cortactin. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 259–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weaver A. M., Karginov A. V., Kinley A. W., Weed S. A., Li Y., Parsons J. T., Cooper J. A. (2001) Cortactin promotes and stabilizes Arp2/3-induced actin filament network formation. Curr. Biol. 11, 370–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Murphy D. A., Courtneidge S. A. (2011) The “ins” and “outs” of podosomes and invadopodia: characteristics, formation, and function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 413–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]