Background: The archaic translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane (ATOM) from Trypanosoma brucei mediates protein import.

Results: ATOM forms a hydrophilic transmembrane pore with channel characteristics resembling bacterial-type protein translocases.

Conclusion: ATOM descended from a bacterial porin and represents an evolutionary intermediate.

Significance: ATOM presumably represents the missing link between the mitochondrial outer membrane protein import pore and its bacterial ancestors.

Keywords: Electrophysiology, Evolution, Mitochondria, Protein Targeting, Protein Translocation, Trypanosoma brucei, Archaic Translocase of the Outer Mitochondrial Membrane

Abstract

Mitochondria are of bacterial ancestry and have to import most of their proteins from the cytosol. This process is mediated by Tom40, an essential protein that forms the protein-translocating pore in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Tom40 is conserved in virtually all eukaryotes, but its evolutionary origin is unclear because bacterial orthologues have not been identified so far. Recently, it was shown that the parasitic protozoon Trypanosoma brucei lacks a conventional Tom40 and instead employs the archaic translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane (ATOM), a protein that shows similarities to both eukaryotic Tom40 and bacterial protein translocases of the Omp85 family. Here we present electrophysiological single channel data showing that ATOM forms a hydrophilic pore of large conductance and high open probability. Moreover, ATOM channels exhibit a preference for the passage of cationic molecules consistent with the idea that it may translocate unfolded proteins targeted by positively charged N-terminal presequences. This is further supported by the fact that the addition of a presequence peptide induces transient pore closure. An in-depth comparison of these single channel properties with those of other protein translocases reveals that ATOM closely resembles bacterial-type protein export channels rather than eukaryotic Tom40. Our results support the idea that ATOM represents an evolutionary intermediate between a bacterial Omp85-like protein export machinery and the conventional Tom40 that is found in mitochondria of other eukaryotes.

Introduction

Mitochondria descended through endosymbiosis from an α-proteobacterium that was assimilated by its host more than 1.5 billion years ago. They were converted over time to nucleus-controlled organelles serving as specialized respiratory and metabolic compartments. In the course of evolution, most genes inherited from the endosymbiont were either lost or transferred to the nucleus, resulting in a radically reduced genome in present day mitochondria.

Accordingly, the nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins are synthesized in the cytosol and subsequently transferred to their respective destinations by a specialized protein translocation system. This machinery often comprises converted bacterial proteins complemented with new subunits of eukaryotic origin (1–6). The proteinaceous pore forming the mitochondrial entry gate for nuclear-encoded proteins is usually formed by Tom40,6 a β-barrel protein conserved in mitochondria of almost all eukaryotes (3, 6, 7).

Trypanosoma brucei is one of the oldest eukaryotic lineages. Several of its mitochondrial proteins are closely related to bacterial ancestors, including a cardiolipin synthase, a mitochondrial calcium uniporter, and a β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (8–10), and therefore support the basal position of T. brucei at the root of phylogenetic tree of eukaryotes (11). Initially, all attempts to identify a Tom40 homologue in the parasitic protozoan T. brucei failed. In contrast, the other member of the porin-3 family, VDAC (12), as well as two highly diverged VDAC-like proteins could readily be identified (13).

The first component of the elusive trypanosomal outer membrane protein import machinery, termed archaic translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane (ATOM), was then identified by a biochemical approach (14). The protein is essential for cell viability and mediates import of nuclear-encoded proteins into trypanosomal mitochondria both in vivo and in vitro. Reciprocal PSI-BLAST searches using the ATOM sequence of several trypanosomatid species revealed a similarity to the bacterial Omp85 family protein YtfM/TamA, which was recently shown to be involved in protein translocation across the outer membrane of Proteobacteria (14, 15). After the identification of ATOM, it was reported that the protein also has some similarity to the canonical Tom40 that initially was missed (16). This raised the interesting possibility that ATOM might be an evolutionary intermediate that shares sequence similarity with both bacterial YtfM/TamA and mitochondrial Tom40, respectively.

We now examined by use of the planar lipid bilayer technique the capability of ATOM to form a hydrophilic conduit for unfolded preproteins. The principal function of providing a channel for unfolded proteins is identical between several bacterial and eukaryotic protein translocases. However, a detailed analysis of single channel properties, such as gating behavior, response to channel-specific substrates, and numbers of pores per active unit, provides defining features allowing the differentiation of protein import channels.

Here we show that recombinant ATOM forms a membrane pore with single channel characteristics that allow for protein translocation across the mitochondrial outer membrane of T. brucei. Moreover, we could show that the number of pores per active unit and the gating pattern of recombinant ATOM resemble bacterial-type protein translocation pores rather than recombinant Tom40.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Materials were obtained from the following sources. Lipids were from Larodan; nonanoyl-N-methylglucamide was synthesized by Dr. S. Korneev, University of Osnabrück); CALBIOSORB adsorbent was from Merck; Q Sepharose fast flow was from GE Healthcare; RTS Wheat Germ CECF (continuous exchange cell-free) system and RTS Wheat Germ LinTempGenSet His6 tag were from 5 Prime; horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-coupled Penta-His antibody was from Qiagen; and Nycodenz was from Axis Shield. Further materials were purchased from standard commercial sources (chemicals in analytical grade).

Purification and Reconstitution of Recombinant ATOM

The sequence of ATOM (TriTrypDB: Tb09.211.1240) was amplified from genomic DNA by PCR using primers CCGCTCGAGATGCTGAAGGAATGGCTTCG and CGCGGATCCTTAGGCAGTGAATACCACAC. The PCR product was cloned into pET15b and transformed into Escherichia coli strain XL-1 blue. Positive clones were verified by DNA sequencing. The plasmid DNA was transformed into E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) for expression. For protein purification, bacteria were grown in 1-liter cultures, induced with 1 mm isopropylthiogalactoside at an A600 of ∼0.6, and harvested after 4 h. The ATOM protein was purified from inclusion bodies. Briefly, cells were lysed by sonication in 50 ml of extraction buffer (20 mm Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 4 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm PMSF) per liter of the original culture. DNase I (0.08 mg/ml) was added in the presence of 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 for 10 min. Inclusion bodies were sedimented and washed consecutively in 20 ml of 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100; 50 ml of TEND (TEND: 50 mm Tris/HCL, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm DTT) containing 2% (v/v) Triton X-100; 100 ml of TEND/no Triton X-100; and finally in 20 ml of TN (TN: 50 mm Tris/HCL, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl). The purified inclusion bodies were solubilized in a buffer containing 8 m urea; 10 mm Tris/HCl, pH 8.0; 100 mm NaH2PO4; 400 mm NaCl; and 20 mm imidazole. The solubilized protein was subjected to immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (IMAC) using Ni2+. To minimize potential contaminations in the IMAC, bound protein was challenged with 10 column volumes of wash buffer 1 (8 m urea, 10 mm Tris, pH 6.3, 100 mm NaH2PO4, 400 mm NaCl, 100 mm imidazole) and wash buffer 2 (8 m urea, 10 mm Tris, pH 5.9, 100 mm NaH2PO4, 400 mm NaCl). The protein was eluted at pH 4.2 (elution buffer: 8 m urea, 10 mm Tris, pH 4.2, 100 mm NaH2PO4, 400 mm NaCl).

The sample was further purified by anion exchange chromatography in flow-through mode (in 8 m urea, 10 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris/HCl, pH 8.1, supplemented with protease inhibitors). The second purification step was essential to remove trace contamination from bacterial outer membrane porins (17) that had been detected in the IMAC eluate by electrophysiological and mass spectrometric analysis.

For reconstitution, the protein solution was supplemented with 2% SDS. Preformed liposomes (50 mg/ml l-α-phosphatidylcholine from egg in 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm MOPS/Tris, pH 7.0) were solubilized with 80 mm nonanoyl-N-methylglucamide and added to a protein/lipid ratio between 1/500 and 1/2500 (mol/mol). After incubation for 15 min at room temperature, detergent and urea were removed by dialysis initially for 2 h at room temperature and subsequently overnight at 4 °C with the inclusion of CALBIOSORB adsorbent into the dialysis cup for efficient SDS removal.

Tom40 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae was produced and purified as described previously (7). The reconstitution procedure was the same as applied for ATOM.

Cell-free Expression and Purification of ATOMwg

The primary template was generated from trypanosomal genomic DNA with primers CTTTAAGAAGGAGATATACCATGCTGAAGGAATGGCTTCG and TGATGATGAGAACCCCCCCCGGCAGTGAATACCACACC using KOD polymerase according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purified PCR product was used as template for the RTS Wheat Germ linear template generation set to introduce flanking regions as well as a C-terminal His6 tag. Subsequent cell-free expression was performed using the RTS Wheat Germ CECF system according to manufacturer's instructions. The in vitro translation products (ATOMwg) from four 50 μl reactions were pooled, mixed with lysis buffer (0.5% SDS, 30 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.9, 300 mm NaCl, 5 mm imidazole) to a final volume of 1.5 ml, solubilized for 3 min at 55 °C, and bound to Ni-NTA agarose beads (200 μl; equilibrated with lysis buffer) for 1 h at room temperature. After eight washing steps with wash buffer (0.5% SDS, 30 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.9, 300 mm NaCl, 10 mm imidazole), elution was accomplished with the buffer as above including 300 mm imidazole. Expression and purification were monitored by SDS-PAGE (10% (w/v) polyacrylamide Tris/glycine gels) and immunoblotting using an HRP-coupled Penta-His antibody.

Density Gradient Centrifugation

Density gradient centrifugation in discontinuous Nycodenz gradients was performed to distinguish solubilized or aggregated proteins from proteoliposomes. An aliquot of proteoliposomes (5 μl) was covered with a discontinuous Nycodenz gradient (0.7 ml 40%, 0.7 ml 20%, 0.7 ml 10%, 0.7 ml 5%, 0.35 ml of buffer) in 100 mm KCl, 10 mm MOPS/Tris, pH 7.0. The gradients were centrifuged for 1 h at 200,000 × g and separated into nine fractions (350 μl each). Subsequently, the protein content of the fractions was precipitated with 20% trichloroacetic acid. The pellet was rinsed with ice-cold acetone and dried at 45 °C. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. The same procedure was applied to solubilized ATOM protein serving as a negative control.

Single Channel Recordings from Planar Lipid Bilayers

Planar lipid bilayer measurements were performed as described previously (18). Single channel currents were recorded using a patch clamp amplifier (GeneClamp 500, Axon Instruments) with a CV-5-1G Headstage (Axon Instruments) and filtered with the inbuilt four-pole Bessel low pass filter at 5 kHz. For data acquisition at a sampling rate of 50 kHz, a personal computer equipped with a DigiData 1200 (Axon Instruments) and Clampex 9 software was used. Voltage ramps were conducted with a rate of 7.5 or 15 mV/s. The denomination cis and trans corresponds to the half-chambers of the bilayer unit. Reported membrane potentials are always referred to the trans compartment.

Single channel analysis was essentially performed as summarized in Ref. 17. Channel insertion into the bilayer occurred mostly unidirectionally. Those channels integrated in reverse orientation were replotted for analysis. Gating transition amplitudes were analyzed and subsequently filtered for dwell times exceeding 0.1 ms (corresponding to five times the sampling interval) to exclude flickering, i.e. incompletely resolved gating transitions, from the analysis (19).

The construction of mean-variance histograms is described by Patlak (20). In short, data were analyzed using a sliding window of 25 data points. Mean currents in these windows were plotted against the respective variance. The frequency distribution of mean-variance data pairs is color-coded. The DLDH peptide representing the N-terminal 9 amino acids (MFRRCFPIF) of T. brucei dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (DLDH) was produced by GenScript and dissolved in 10 mm MOPS/Tris, pH 7.

RESULTS

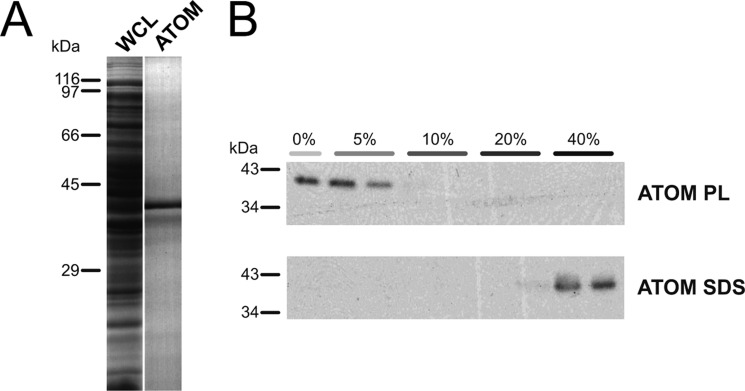

T. brucei ATOM with a C-terminal His tag was expressed in E. coli and isolated from inclusion bodies via Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (Fig. 1A). Further purification of ATOM was achieved by anion exchange chromatography in flow-through mode. Following the second purification step, we reconstituted ATOM into liposomes and assessed whether it was properly integrated using Nycodenz density gradient flotation (Fig. 1B) ATOM solubilized in SDS was detected in the high density fractions of the gradient, whereas reconstituted ATOM migrated to fractions of lower density, indicating the successful formation of proteoliposomes.

FIGURE 1.

ATOM from T. brucei was produced in E. coli, purified, and reconstituted into proteoliposomes. A, purification of ATOM from E. coli whole cell lysate (WCL) via IMAC. B, Nycodenz gradient flotation of ATOM proteoliposomes (ATOM PL) and purified protein in 2% SDS (ATOM SDS). Fractionated gradients (percentages indicate Nycodenz content) were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and detected by immunodecoration with anti-His-HRP antibodies.

Using these ATOM proteoliposomes for lipid bilayer measurements, we reproducibly obtained a consistent type of single channel activity. Current traces displayed single channels with a total conductance of Gtotal ≅ 1.2–1.7 nS ([KCl] = 250 mm) that mainly reside in an open conformation with infrequent short gating transitions to several subconductance states. After a single proteoliposome fusion event with the bilayer, complete channel closure at membrane potentials > ±120 mV always occurred in three steps or in a multiple of three distinct steps (Fig. 2A, upper panel). This characteristic is typically observed with bacterial outer membrane porins such as PorB, OmpF, or PhoE, which form homotrimers comprising three identical pores (21–25).

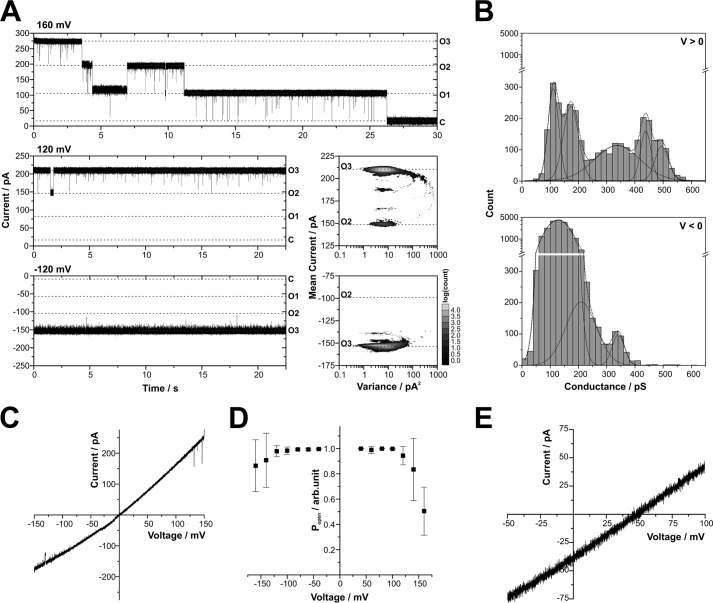

FIGURE 2.

Single channel characteristics of purified ATOM produced in E. coli. A, single channel traces exhibit three equally sized pores, marked by horizontal dashed lines, with O3, O2, and O1 for the number of open pores and C for the closed state of the complete trimeric channel unit. Similar but less frequent tripartite closure was observed at negative voltages (data not shown). Different patterns of gating transitions are observed at positive and negative voltages (±120 mV). Mean-variance plots (right panel) represent the same traces (total duration 30 s). B, frequency distribution of single channel gating transitions (n = 8 single channels). Gating amplitudes (τ > 0.1 ms) were: 110 ± 20, 170 ± 30, 340 ± 80, 440 ± 30, and 495 ± 25 pS at positive voltages and 130 ± 35, 210 ± 55, and 340 ± 20 pS at negative voltages (rectification: Gmax+/Gmax− ≈ 1.45). All conductance peaks can be mapped to transitions in the correspondent Mean-variance histogram in A. C, the voltage-dependent current of a single channel indicates rectification with higher conductivity at positive potentials. D, the open probability of single channels (n = 8) is close to 100% over a broad range of voltages, decreasing to about 50 and 80% at positive and negative voltages, respectively. Error bars indicate S.D. arb.unit, arbitrary units. E, a reversal potential of 48.4 ± 0.8 mV was determined from voltage ramps (n = 3 single channels). Buffer conditions were symmetric with 250 mm KCl, 10 mm MOPS/Tris, pH 7, in cis and trans (A–D) or asymmetric with 250/20 mm KCl, 10 mm MOPS/Tris, pH 7, in cis/trans (E).

At lower voltages, the gating behavior of the ATOM channel was dependent on the direction of the transmembrane electric field (Fig. 2A). This became more obvious from the statistical representation of the current traces by mean-variance histograms calculated according to Patlak (20). These three-dimensional plots depict a complete current trace of 30 s with the data point accumulations at low variances representing stable conductance states in which the channel resides for some time. The parabolic connections mark gating transitions between these states. At positive voltages, the single pore exhibited infrequent short gating transitions between at least four distinct conductance states. More frequent, but much shorter gating events were detected at negative voltages. Apparently, the latter were for the most part not completely resolved within the 20-μs sampling intervals. These partial gating transitions distorted the low variance region, which corresponds to the open state, toward higher variances (Fig. 2A, right panel).

The analysis of the gating transition amplitudes confirmed these asymmetric channel properties (Fig. 2B). A voltage-dependent frequency distribution of conductance changes was found with the largest amplitudes observed in the range of Gmax ≅ 400–500 pS at positive potentials and Gmax ≅ 300–400 pS at negative potentials. These gating transitions corresponded to the closure of a single pore in the trimeric channel unit. Amplitudes of gating to subconductance levels at positive potentials clustered around Gsub ≅ 100–200 pS, whereas at negative potentials, a broad distribution of Gsub ≅ 50–250 pS was observed (Fig. 2).

Using a simplified model that approximates the cross-sectional volume of the constricted region inside the pore by a cylinder, a theoretical pore diameter can be calculated based on measured conductance values (26). Assuming a pore depth of 1–5 nm and a 5-fold reduced mobility of small cations within the restriction zone (27), the single pore conductance of Gmax ≅ 400 pS corresponds to a pore diameter of 2.0 ± 0.4 nm. This would be large enough to accommodate an extended peptide chain or an α-helix.

In agreement with the conductance distribution, single trimeric channel units exhibited a voltage-dependent current with higher conductance at positive voltages (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, the voltage dependence of the channel open probability shown in Fig. 2D revealed that the channel mostly resides in an open conformation with the open probability only decreasing at voltages exceeding ±120 mV. This voltage-dependent closure was more pronounced at positive voltages.

In asymmetric buffer conditions ([KCl]cis/trans = 250/20 mm), the reversal potential was Erev = 48.4 mV. The corresponding permeability ratio calculated by the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz voltage equation denotes a marked selectivity for potassium over chloride (PK+:PCl−). In summary, proteoliposomes containing purified ATOM comprised a large, hydrophilic, cation-selective channel displaying a single pore conductance of Gmax ≅ 400 pS.

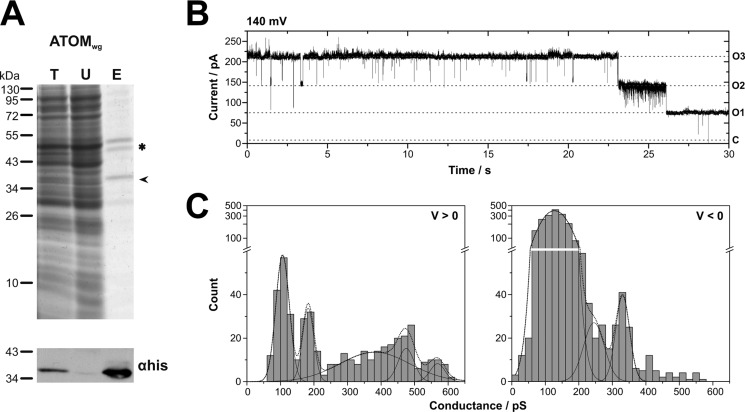

To further corroborate that the observed channels are formed by ATOM, the trypanosomal protein was produced in a cell-free wheat germ expression system and purified from the translation mix using Ni-NTA (Fig. 3A). This in vitro translation product is herein after referred to as ATOMwg. The protein was reconstituted into proteoliposomes as described above. Fusion of the ATOMwg proteoliposomes with the planar lipid bilayer resulted in the integration of ion-permeable channels with single channel characteristics matching those observed for ATOM produced in E. coli. (i) Channel closure occurred in three distinct steps, preferably at high voltages (Fig. 3B). (ii) Frequency distributions of conductance changes revealed the same pattern of gating transition amplitudes as observed before. At positive voltages, small conductance changes clustered around Gsub ≅ 100–200 pS, and larger gating transitions were within the range of Gmax ≅ 400–600 pS, whereas at negative voltages, a broad distribution of frequent, small conductance changes was observed (Gsub ≅ 50–250 pS), and the largest amplitudes ranged around Gmax ≅ 300–400 pS (Fig. 3C). (iii) Similar selectivity (Erev ≅ 46 mV) and a voltage-dependent open probability could also be confirmed (details not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Single channel characteristics of ATOMwg produced by cell-free expression in a wheat germ system. A, ATOMwg was purified via its C-terminal His6 tag using Ni-NTA. Total translation reaction (T), unbound fraction (U), and 2-fold concentrated eluate (E) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (top) and immunoblot using α-His-HRP (bottom). The migration position of ATOMwg is indicated by an arrowhead. The impurity (double band ∼50 kDa) marked with an asterisk is a constituent of the wheat germ extract known to be co-purified by Ni-NTA. B, single channel current traces reveal complete channel closure in three distinct steps marked by horizontal dashed lines, with O3, O2, and O1 for the number of open pores and C for the closed state of the complete trimeric channel unit. C, the voltage-dependent gating behavior is reflected in the frequency distributions of gating transition amplitudes (n = 3 single channels; τ > 0.1 ms): 110 ± 20, 180 ± 15, 380 ± 100, 475 ± 25, and 570 ± 20 pS at positive voltages and 130 ± 35, 245 ± 30, and 330 ± 20 pS at negative voltages. Buffer conditions were symmetric with 250 mm KCl, 10 mm MOPS/Tris, pH 7, in cis and trans.

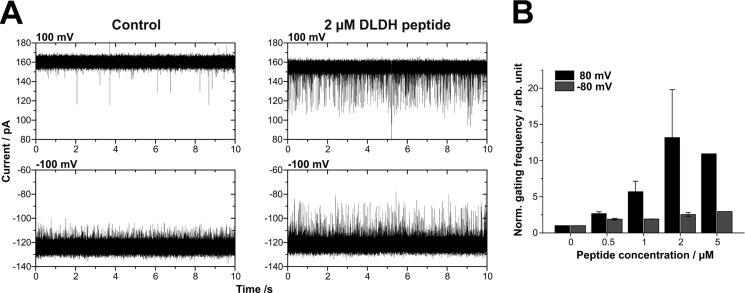

In previous studies, specific interactions of natural substrates with the respective channel proteins have helped to identify and characterize the pore forming subunits of protein import complexes (7, 18, 28). Accordingly, we investigated whether the channel formed by reconstituted ATOM responded to the presence of a peptide representing the N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence of the trypanosomal dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase, (hereinafter designated as DLDH peptide) a natural substrate of the ATOM channel (29, 30). The addition of the presequence peptide even at low concentration (0.5 μm) to both sides of the channel resulted in an increased frequency of conductance changes (Fig. 4). The effect could be reversed by removing the peptide through perfusion of the bilayer chambers.

FIGURE 4.

ATOM single channels respond to a genuine mitochondrial presequence from T. brucei in a side-specific manner. A, current traces of a single channel depict the increased frequency of conductance changes upon the addition of 2 μm DLDH peptide. B, the gating frequency in the presence of increasing peptide concentrations was normalized with respect to the gating frequency in the absence of peptide (n ≥ 2; 4 single channels). In the presence of 5 μm peptide, the gating frequency could only be measured for one channel. Buffer conditions were symmetric with 250 mm KCl, 10 mm MOPS/Tris, pH 7, in cis and trans. Error bars indicate S.D.

In the absence of peptides, the channels intrinsically exhibited more frequent gating transitions at negative than at positive voltages (Figs. 2B and 4A); thus the relative gating frequency of single channels at increasing peptide concentrations was analyzed in detail. Fig. 4B displays an increased frequency of conductance changes after peptide addition at positive voltages, whereas the frequency at negative voltages hardly changed. Because the DLDH peptide was positively charged (z = +2 at pH 7), the application of positive voltage with the simultaneous addition of the DLDH peptide to both sides of the membrane directed peptides from the trans to the cis compartment and vice versa. Consequently, the interaction of the peptide with the ATOM channel was enhanced from one side of the channel, which remarkably corresponds to the high conducting side of ATOM (Figs. 2C and 4). This demonstrated that one of the vestibules of the channel specifically interacts with the presequence peptide at low concentrations, whereas the opposite vestibule is only occasionally blocked in an unspecific fashion by peptides that are randomly driven into the pore by electrophoretic movement. A similar but less pronounced side specificity has been observed with recombinant Tom40 (7, 31).

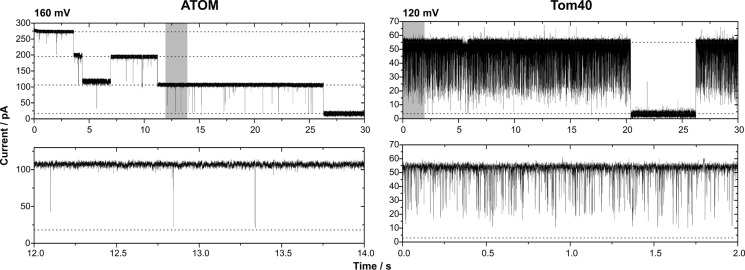

Finally, we compared the single channel activity of ATOM with the one of Tom40 (Fig. 5). To that end, the Tom40 protein from S. cerevisiae was recombinantly expressed, purified, and reconstituted into proteoliposomes (7, 28). For better comparability, the same reconstitution protocol was used as for ATOM. The observed Tom40 single channels exhibited the same characteristics as published previously (7, 28). In short, these are: (i) a single channel conductance of ∼400 pS ([KCl] = 250 mm); (ii) integration into the membrane in the form of a single pore, which is able to close in one step at voltages beyond ± 80 mV; and (iii) a gating behavior that is dominated by fast flickering into a prominent subconductance state. A similar gating mode can also be observed with the closely related mitochondrial porin VDAC (32).

FIGURE 5.

Recombinant ATOM forms a high conductance channel with a characteristic gating behavior setting it apart from Tom40. A current trace of a lipid bilayer containing a single ATOM channel is displayed (left panel; same as in Fig. 2A). As indicated by dashed lines, complete closure of the channel occurs in three distinct steps, each representing an independent pore. In the case of recombinant Tom40 (right panel), an active single channel unit consists of one pore (dashed lines), closing for longer periods in one step at voltages above ±80 mV and apart from that displaying fast flickering into a subconductance state or the closed state. The lower panel illustrates the gating behavior of a single pore by enlargement of the sections highlighted in gray in the upper current traces. Buffer conditions were symmetric with 250 mm KCl, 10 mm MOPS/Tris, pH 7, in cis and trans.

DISCUSSION

Functional studies have shown that ATOM mediates import of nuclear-encoded proteins into the mitochondrion of T. brucei (14). Based on our electrophysiological studies, we now conclude that ATOM is the central pore-forming subunit of the mitochondrial outer membrane protein import machinery in T. brucei. We demonstrated that it constitutes a wide hydrophilic channel (d ≅ 2 nm) with a conductance of Gmax ≅ 400 pS per pore that exhibits selectivity for cations. These basic characteristics are common features of several protein-conducting nanopores (Table 1) and may allow the translocation of mainly unfolded proteins with positively charged N-terminal presequences (7, 18, 31).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of single channel properties determined for recombinantly produced protein translocases

Buffer conditions for the determination of Gmax were symmetric with 250 mm KCl, 10 mm MOPS/Tris, pH 7.0, in cis and trans, and PK+:PCl− was calculated from reversal potentials measured under asymmetric buffer conditions with 250/20 mm KCl, 10 mm MOPS/Tris, pH 7, in cis/trans.

| Gmax | PK+:PCl− | No. of pores | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATOM (T. brucei) | 400 pS | 14 | 3 | This study |

| Toc75 (Pisum sativum) | 450–500 pS | 14.3 | ≥3a | 18, 40 |

| synToc75 (Synechocystis) | 410 pS | 11.1 | ≥3a | 38 |

| Tom40 (S. cerevisiae) | 370 pS | 8–10 | 1 | 7, 28 |

| Tom40 (N. crassa) | 390–500 pS | 3b–9 | 1–2 | 28, 47 |

a Denotes number of pores determined from multichannel experiments (with the smallest number of simultaneous integrations equaling three pores) or cross-linking of reconstituted proteins.

b Determined in 100/10 mm KCl, 10 mm MOPS/Tris, pH 7, in cis/trans.

We could show that the channel formed by ATOM has the ability to specifically interact with the genuine mitochondrial presequence from trypanosomal dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase in a side-dependent manner. The reversible interaction between the peptide and the channel transiently blocks the passage of ions through the ATOM pore. Using a specific mitochondrial presequence peptide in a concentration range of 1–20 μm, a similar effect has previously been observed for Tom40 of yeast (7, 28, 31, 33). Interactions of even lower concentrated peptides (20 nm) with protein translocases have only been observed for Toc75, the translocase of the outer envelope of chloroplasts. However, that effect was measured at considerably lower salt concentrations, where reduced screening of charges allows for stronger electrostatic interactions (18). The low concentrations at which the peptide effect is observed in our experiments as well as its pronounced side specificity are strong indicators for a specific interaction between the ATOM channel and the trypanosomal presequence.

The single channel characteristics of ATOM such as rectification, selectivity, asymmetric gating behavior, and asymmetric peptide interaction indicate an asymmetric topology of the pore in terms of charge distribution and/or the shape of the vestibules (34, 35). In particular, the side of higher conductance coincides with the side from which the peptide effect is more prominent. This property might help to define the directionality of preprotein transport from the cytoplasmic to the intermembrane space side of the outer mitochondrial membrane.

The general characteristics of the ATOM pore are consistent with basic features observed for protein translocases of different origin, i.e. mitochondrial Tom40 and plastid Toc75 (Table 1). However, the detailed analysis of single channel properties reveals a pronounced disparity between the channels formed by ATOM and Tom40, respectively. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the gating behavior of recombinant Tom40 single channels is dominated by fast flickering into a prominent subconductance state, and full pore closure occurs in a single step (7, 28). This contrasts with the tripartite channel closure and low frequency gating that is observed for recombinant ATOM. Certainly, the oligomeric assembly observed for the recombinant proteins reflects the number of β-barrels required for stable integration into the bilayer in the absence of accessory proteins (36). However, it does not necessarily represent the number of pores found in vivo in the respective heterooligomeric protein translocation complexes. Native TOM complexes purified from mitochondrial outer membranes of S. cerevisiae and Neurospora crassa, for example, were shown to contain two identical Tom40 pores (28, 37).

Our analysis, however, reveals common properties of recombinant ATOM and recombinant Toc75 from plastids and cyanobacteria (synToc75) (18, 38). These are: (i) a homotrimeric assembly, which for recombinant Toc75 was confirmed by cryo-electron microscopy, cross-linking, and other methods (39, 40); and (ii) a gating behavior that is characterized by infrequent, short gating events between several conductance states (18). The concordant single channel characteristics of Toc75 and its distant homologue synToc75 from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 corroborated the development of the chloroplast protein import pore from a preexisting bacterial Omp85-like porin (38). In summary, these common features might indicate that Toc75 as well as ATOM are both derived from bacterial ancestors, which probably were outer membrane porins.

Our results are therefore consistent with the previously suggested similarity between ATOM and a bacterial protein translocase of the Omp85 family, specifically YtfM/TamA, which was recently shown to promote efficient translocation of several bacterial proteins (14, 15). Electrophysiological data available for bacterial Omp85 family members that were implicated in protein translocation reveal similar general characteristics. However, in-depth single channel analyses (i.e. conductance states, gating, selectivity, interaction with natural substrates) that would allow for a detailed comparison with our ATOM measurements are lacking (41–46).

In conclusion, ATOM forms a hydrophilic pore, which meets all requirements of a mitochondrial outer membrane protein translocation channel. Our work supports the model that ATOM represents an evolutionary relic in which the origin of the mitochondrial outer membrane translocase from a bacterial Omp85-type protein export machinery is still detectable on both the sequence as well as on the functional level.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stefan Walter (University of Osnabrück) for help with the mass spectrometric analysis and Tom Alexander Götze (University of Cambridge) for helpful discussion.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Grant WA681/2-1 (to R. W.) and DFG Grant FOR967 (to R. W.), by DFG Grant ME1921 (to C. M.), by Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) Grant 31003A_13855 (to A. S.) as well as by Swiss National Science Foundation grant PP00P3_128419 and European Research Council FP7 Contract MOMP 281764 (to S. H.).

This article was selected as a paper of the week.

- Tom

- translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane

- ATOM

- archaic translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane

- VDAC

- voltage-dependent anion channel

- IMAC

- immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- S

- siemens.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gross J., Bhattacharya D. (2009) Mitochondrial and plastid evolution in eukaryotes: an outsiders' perspective. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 495–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cavalier-Smith T. (2006) Origin of mitochondria by intracellular enslavement of a photosynthetic purple bacterium. Proc. Biol. Sci. 273, 1943–1952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dolezal P., Likic V., Tachezy J., Lithgow T. (2006) Evolution of the molecular machines for protein import into mitochondria. Science 313, 314–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dyall S. D., Brown M. T., Johnson P. J. (2004) Ancient invasions: from endosymbionts to organelles. Science 304, 253–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Herrmann J. M. (2003) Converting bacteria to organelles: evolution of mitochondrial protein sorting. Trends Microbiol. 11, 74–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hewitt V., Alcock F., Lithgow T. (2011) Minor modifications and major adaptations: the evolution of molecular machines driving mitochondrial protein import. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808, 947–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hill K., Model K., Ryan M. T., Dietmeier K., Martin F., Wagner R., Pfanner N. (1998) Tom40 forms the hydrophilic channel of the mitochondrial import pore for preproteins. Nature 395, 516–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shah T. D., Hickey M. C., Capasso K. E., Palenchar J. B. (2011) The characterization of a unique Trypanosoma brucei β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 179, 100–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bick A. G., Calvo S. E., Mootha V. K. (2012) Evolutionary diversity of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Science 336, 886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Serricchio M., Bütikofer P. (2012) An essential bacterial-type cardiolipin synthase mediates cardiolipin formation in a eukaryote. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E954–E961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cavalier-Smith T. (2010) Kingdoms Protozoa and Chromista and the eozoan root of the eukaryotic tree. Biol. Lett. 6, 342–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pusnik M., Charrière F., Mäser P., Waller R. F., Dagley M. J., Lithgow T., Schneider A. (2009) The single mitochondrial porin of Trypanosoma brucei is the main metabolite transporter in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 671–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Flinner N., Schleiff E., Mirus O. (2012) Identification of two voltage-dependent anion channel-like protein sequences conserved in Kinetoplastida. Biol. Lett. 8, 446–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pusnik M., Schmidt O., Perry A. J., Oeljeklaus S., Niemann M., Warscheid B., Lithgow T., Meisinger C., Schneider A. (2011) Mitochondrial preprotein translocase of trypanosomatids has a bacterial origin. Curr. Biol. 21, 1738–1743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Selkrig J., Mosbahi K., Webb C. T., Belousoff M. J., Perry A. J., Wells T. J., Morris F., Leyton D. L., Totsika M., Phan M. D., Celik N., Kelly M., Oates C., Hartland E. L., Robins-Browne R. M., Ramarathinam S. H., Purcell A. W., Schembri M. A., Strugnell R. A., Henderson I. R., Walker D., Lithgow T. (2012) Discovery of an archetypal protein transport system in bacterial outer membranes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 506–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zarsky V., Tachezy J., Dolezal P. (2012) Tom40 is likely common to all mitochondria. Curr. Biol. 22, R479–R481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harsman A., Bartsch P., Hemmis B., Krüger V., Wagner R. (2011) Exploring protein import pores of cellular organelles at the single molecule level using the planar lipid bilayer technique. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 90, 721–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hinnah S. C., Wagner R., Sveshnikova N., Harrer R., Soll J. (2002) The chloroplast protein import channel Toc75: pore properties and interaction with transit peptides. Biophys. J. 83, 899–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McManus O. B., Blatz A. L., Magleby K. L. (1987) Sampling, log binning, fitting, and plotting durations of open and shut intervals from single channels and the effects of noise. Pflugers Arch. 410, 530–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Patlak J. B. (1993) Measuring kinetics of complex single ion channel data using mean-variance histograms. Biophys. J. 65, 29–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mauro A., Blake M., Labarca P. (1988) Voltage gating of conductance in lipid bilayers induced by porin from outer membrane of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 1071–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kozjak-Pavlovic V., Dian-Lothrop E. A., Meinecke M., Kepp O., Ross K., Rajalingam K., Harsman A., Hauf E., Brinkmann V., Günther D., Herrmann I., Hurwitz R., Rassow J., Wagner R., Rudel T. (2009) Bacterial porin disrupts mitochondrial membrane potential and sensitizes host cells to apoptosis. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Engel A., Massalski A., Schindler H., Dorset D. L., Rosenbusch J. P. (1985) Porin channel triplets merge into single outlets in Escherichia coli outer membranes. Nature 317, 643–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dargent B., Hofmann W., Pattus F., Rosenbusch J. P. (1986) The selectivity filter of voltage-dependent channels formed by phosphoporin (PhoE protein) from E. coli. EMBO J. 5, 773–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Delcour A. H. (2002) Structure and function of pore-forming β-barrels from bacteria. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4, 1–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hille B. (1992) Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes, Third Ed., pp. 291–296, Sinauer, Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smart O. S., Breed J., Smith G. R., Sansom M. S. (1997) A novel method for structure-based prediction of ion channel conductance properties. Biophys. J. 72, 1109–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Becker L., Bannwarth M., Meisinger C., Hill K., Model K., Krimmer T., Casadio R., Truscott K. N., Schulz G. E., Pfanner N., Wagner R. (2005) Preprotein translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane: reconstituted Tom40 forms a characteristic TOM pore. J. Mol. Biol. 353, 1011–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hauser R., Pypaert M., Häusler T., Horn E. K., Schneider A. (1996) In vitro import of proteins into mitochondria of Trypanosoma brucei and Leishmania tarentolae. J. Cell Sci. 109, 517–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Häusler T., Stierhof Y. D., Blattner J., Clayton C. (1997) Conservation of mitochondrial targeting sequence function in mitochondrial and hydrogenosomal proteins from the early-branching eukaryotes Crithidia, Trypanosoma, and Trichomonas. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 73, 240–251 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harsman A., Krüger V., Bartsch P., Honigmann A., Schmidt O., Rao S., Meisinger C., Wagner R. (2010) Protein-conducting nanopores. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 22, 454102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Báthori G., Szabó I., Schmehl I., Tombola F., Messina A., De Pinto V., Zoratti M. (1998) Novel aspects of the electrophysiology of mitochondrial porin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 243, 258–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mahendran K. R., Romero-Ruiz M., Schlösinger A., Winterhalter M., Nussberger S. (2012) Protein translocation through Tom40: kinetics of peptide release. Biophys. J. 102, 39–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Im W., Roux B. (2002) Ion permeation and selectivity of OmpF porin: a theoretical study based on molecular dynamics, Brownian dynamics, and continuum electrodiffusion theory. J. Mol. Biol. 322, 851–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schirmer T., Phale P. S. (1999) Brownian dynamics simulation of ion flow through porin channels. J. Mol. Biol. 294, 1159–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Naveed H., Jackups R., Jr., Liang J. (2009) Predicting weakly stable regions, oligomerization state, and protein-protein interfaces in transmembrane domains of outer membrane proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12735–12740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Künkele K. P., Juin P., Pompa C., Nargang F. E., Henry J. P., Neupert W., Lill R., Thieffry M. (1998) The isolated complex of the translocase of the outer membrane of mitochondria: characterization of the cation-selective and voltage-gated preprotein-conducting pore. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 31032–31039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bölter B., Soll J., Schulz A., Hinnah S., Wagner R. (1998) Origin of a chloroplast protein importer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 15831–15836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schleiff E., Soll J., Küchler M., Kühlbrandt W., Harrer R. (2003) Characterization of the translocon of the outer envelope of chloroplasts. J. Cell Biol. 160, 541–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bredemeier R., Schlegel T., Ertel F., Vojta A., Borissenko L., Bohnsack M. T., Groll M., von Haeseler A., Schleiff E. (2007) Functional and phylogenetic properties of the pore-forming β-barrel transporters of the Omp85 family. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 1882–1890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stegmeier J. F., Glück A., Sukumaran S., Mäntele W., Andersen C. (2007) Characterization of YtfM, a second member of the Omp85 family in Escherichia coli. Biol. Chem. 388, 37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Méli A. C., Hodak H., Clantin B., Locht C., Molle G., Jacob-Dubuisson F., Saint N. (2006) Channel properties of TpsB transporter FhaC point to two functional domains with a C-terminal protein-conducting pore. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 158–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Clantin B., Delattre A. S., Rucktooa P., Saint N., Méli A. C., Locht C., Jacob-Dubuisson F., Villeret V. (2007) Structure of the membrane protein FhaC: a member of the Omp85-TpsB transporter superfamily. Science 317, 957–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jacob-Dubuisson F., El-Hamel C., Saint N., Guédin S., Willery E., Molle G., Locht C. (1999) Channel formation by FhaC, the outer membrane protein involved in the secretion of the Bordetella pertussis filamentous hemagglutinin. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37731–37735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ertel F., Mirus O., Bredemeier R., Moslavac S., Becker T., Schleiff E. (2005) The evolutionarily related β-barrel polypeptide transporters from Pisum sativum and Nostoc PCC7120 contain two distinct functional domains. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28281–28289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Duret G., Szymanski M., Choi K. J., Yeo H. J., Delcour A. H. (2008) The TpsB translocator HMW1B of Haemophilus influenzae forms a large conductance channel. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 15771–15778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Künkele K. P., Heins S., Dembowski M., Nargang F. E., Benz R., Thieffry M., Walz J., Lill R., Nussberger S., Neupert W. (1998) The preprotein translocation channel of the outer membrane of mitochondria. Cell 93, 1009–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]