Background: The motif of human cMyBP-C contains phosphorylation sites that regulate its interaction with myosin ΔS2.

Results: The motif interacts with calmodulin in a calcium-dependent manner yet is independent of its phosphorylation state.

Conclusion: Highly conserved residues toward the C-terminal end of the motif interact with calmodulin in an extended conformation.

Significance: Calmodulin can link cMyBP-C with the calcium-signaling pathways in muscle.

Keywords: Calcium Signaling; Calmodulin; Fluorescence; NMR; Protein-Protein Interactions; Cardiac Myosin-binding Protein C; Motif; Small Angle X-ray Scattering; Ca2+ Signaling, Tryptophan Fluorescence

Abstract

The N-terminal modules of cardiac myosin-binding protein C (cMyBP-C) play a regulatory role in mediating interactions between myosin and actin during heart muscle contraction. The so-called “motif,” located between the second and third immunoglobulin modules of the cardiac isoform, is believed to modulate contractility via an “on-off” phosphorylation-dependent tether to myosin ΔS2. Here we report a novel Ca2+-dependent interaction between the motif and calmodulin (CaM) based on the results of a combined fluorescence, NMR, and light and x-ray scattering study. We show that constructs of cMyBP-C containing the motif bind to Ca2+/CaM with a moderate affinity (KD ∼10 μm), which is similar to the affinity previously determined for myosin ΔS2. However, unlike the interaction with myosin ΔS2, the Ca2+/CaM interaction is unaffected by substitution with a triphosphorylated motif mimic. Further, Ca2+/CaM interacts with the highly conserved residues (Glu319–Lys341) toward the C-terminal end of the motif. Consistent with the Ca2+ dependence, the binding of CaM to the motif is mediated via the hydrophobic clefts within the N- and C-lobes that are known to become more exposed upon Ca2+ binding. Overall, Ca2+/CaM engages with the motif in an extended clamp configuration as opposed to the collapsed binding mode often observed in other CaM-protein interactions. Our results suggest that CaM may act as a structural conduit that links cMyBP-C with Ca2+ signaling pathways to help coordinate phosphorylation events and synchronize the multiple interactions between cMyBP-C, myosin, and actin during the heart muscle contraction.

Introduction

The controlled modulation of Ca2+ concentrations within muscle sarcomeres is the primary signaling mechanism used to regulate the sliding of myosin-based thick filaments past actin-based thin filaments to give rise to muscle contraction and relaxation. In striated muscle, Ca2+ activates the thin filament by binding to troponin, thus triggering conformational changes among the thin filament accessory proteins. The result is a shift of tropomyosin on the thin filament that uncovers the binding sites where myosin heads attach to actin and impart force (1). However, there are additional layers of regulation that modulate the contractile cycle. We have previously proposed that the N-terminal modules of cardiac myosin-binding protein C can modulate the thin filament activation response to Ca2+ signals, essentially buffering the Ca2+ response by competing for myosin binding sites on actin while also sterically hindering tropomyosin from relaxing to its Ca2+-off position and thus holding myosin binding sites on actin open (2, 3). Ca2+ signals also regulate the activity of a number of kinases important in muscle action, in a number of instances via the multifunctional intracellular Ca2+ receptor calmodulin (4–6). One such calmodulin-regulated kinase is Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII)3 that phosphorylates a critical regulatory region within cMyBP-C (7, 8).

Calmodulin (CaM) is a small, dumbbell-shaped protein that is a structural homologue of the Ca2+-binding subunit of troponin (TnC), but rather than having a single known regulatory function, CaM binds to a diverse array of target proteins to modulate their functions in response to Ca2+ signals (4–6). The two globular lobes of CaM each contain a pair of Ca2+-binding EF-hand (helix-loop-helix) motifs that are connected by a solvent-exposed helix of ∼8 turns. Upon Ca2+ binding, a hydrophobic cleft opens in each lobe to mediate target protein recognition and binding. In the classical Ca2+/CaM-target protein complexes, the two lobes of CaM wrap around a helical peptide sequence via flexibility in the interconnecting helix (6, 9). Other modes of Ca2+/CaM binding have been observed in which CaM maintains an extended conformation (10–14) similar to those observed for TnC interacting with its regulatory binding partner troponin I (TnI) (15).

Myosin-binding protein C (MyBP-C) was first identified as a thick filament accessory protein and has since been determined to play both structural and regulatory roles in striated muscle contraction (16–18). MyBP-C is a modular protein made up of immunoglobulin (Ig)-type and fibronectin-like modules. An ∼100-residue sequence, referred to as the “motif” (m), sits between two Ig modules near the N terminus (Fig. 1, A and B) and has been implicated in mediating potentially key phosphorylation-dependent interactions in the cardiac isoform (19). Interest in cardiac MyBP-C (cMyBP-C) has been stimulated following the finding that mutations in the gene encoding the cardiac isoform are a leading cause of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (20–22). cMyBP-C contains eight Ig modules and three fibronectin modules, designated C0–C10. The C0 Ig module is cardiac specific and connects to C1 via a proline/alanine-rich linker (Fig. 1A). In addition, there are multiple cardiac specific phosphorylation sites compared with only one in the skeletal isoform (19). The C1-m-C2 fragment (C1C2) binds to myosin ΔS2, close to the lever arm region of the myosin head and primarily via the motif (23, 24). During β-adrenergic stimulation, cMyBP-C undergoes phosphorylation and releases the bound myosin ΔS2, resulting in an acceleration of the cross-bridge cycling rates and force generation (23, 25).

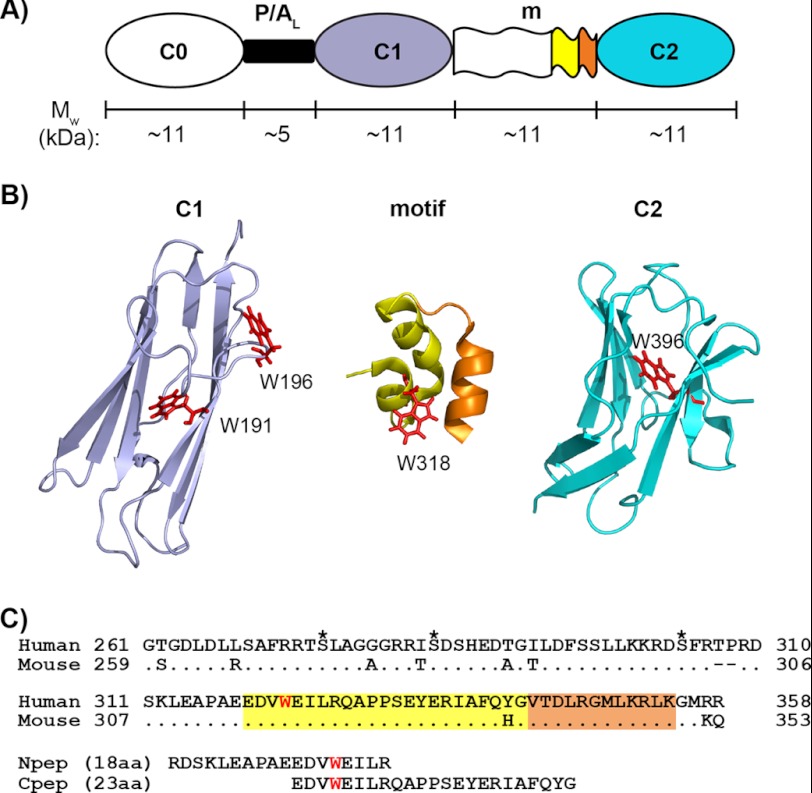

FIGURE 1.

N-terminal modules and the motif of cMyBP-C. A, schematic representation of the three N-terminal Ig modules (C0, C1, and C2) and their connectors: the proline/alanine-rich linker (P/AL) and the motif (m). The approximate molecular weight (Mw) of each region is indicated, and the color coding for different regions of sequence/structure is conserved in panels A, B, and C. B, ribbon diagrams of (from left to right) the human C1 (PDB 2AVG) module, the structured region of mouse motif (residues 315–351) (PDB 2LHU), and the human C2 (PDB 1PD6) module with tryptophan residues (Trp191, Trp196, Trp318, and Trp396) shown as red sticks. Note that Trp318 in the mouse sequence is equivalent to Trp322 in the human sequence. In the mouse motif ribbon diagram (middle), the sequence corresponding to human Cpep used in this study (incorporating Trp318) is shown in yellow, and the remaining sequence is orange. C, sequence alignments of human and mouse cMyBP-C motifs and of human motif peptides (Npep and Cpep). For the human motif, the three putative phosphorylation sites are marked by asterisks above the sequence, and the only tryptophan residue, Trp322, is highlighted in red. Sequences corresponding to the structured region of mouse motif (amino acids (aa) 315–351) are highlighted in yellow and orange as in B. Note that for the human triphosphorylation mimic C1C2EEE, the three putative phosphorylation sites are mutated to glutamates (i.e. S275E/S284E/S304E).

Both CaMKII and protein kinase A (PKA) can phosphorylate cMyBP-C on at least three serines within the motif (Ser275, Ser284, and Ser304 in the human sequence, corresponding to Ser273, Ser282, and Ser302 in mouse) (7, 8, 19, 26) (Fig. 1C). An ordered hierarchy of phosphorylation exists among these sites (23, 27, 28). In the mouse protein, Ser282 is the main target for CaMKII, and, importantly, phosphorylation at this site is necessary to induce further phosphorlyation at Ser273 and Ser302 by PKA. The critical role of Ser282 phosphorylation by CaMKII is highlighted by its links to enhanced contractility after myocardial stunning (29, 30), whereas the loss of cMyBP-C phosphorylation at Ser282 results in altered response to β-adrenergic stimuli (31). The CaMKII-regulated phosphorylation is strictly Ca2+/CaM-dependent and can be inhibited by the Ca2+ chelator EGTA or the CaM-binding peptide sequence from myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) (7, 8, 19, 32). CaMKII inhibition reduces both cMyBP-C and TnI phosphorylation and decreases maximum force through a cross-bridge feedback mechanism (33). Together, the combined evidence suggests that Ca2+/CaM-dependent phosphorylation of cMyBP-C may be a key step for coordinating events in the contractile cycle. When directly isolated from muscle tissue, cMyBP-C is purified with endogenous CaMKII activity (7), suggesting that there is an intimate link between the protein and this Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinase.

In addition to regulating CaMKII activity, Ca2+ signals regulate the activity of the Ca2+/CaM-dependent MLCK that phosphorylates yet another EF-hand relative of CaM, the myosin regulatory light chain (RLC) (34–36). The CaM-dependent phosphorylation of cMyBP-C and RLC contribute to the contraction/relaxation cycle by modifying the local concentration of cross-bridges at the interface with actin (37). The C0 domain of cMyBP-C can directly interact with the RLC (38), whereas the cMyBP-C motif, in an unphosphorylated state, can interact with myosin ΔS2 (24). Therefore, the N-terminal domains of cMyBP-C can interact with both components of myosin proximal to the myosin head and with actin (2, 39). It thus appears that Ca2+ signaling and CaM-dependent mechanisms of phosphorylation in response to these signals are integral to regulating molecular interactions between all three proteins. Because CaM is a pivotal Ca2+ sensor, we asked whether CaM may serve as a structural, Ca2+-sensitive link to the regulatory role of cMyBP-C.

In this study, we have used pull-down assays, size exclusion chromatography with multiple-angle laser light spectroscopy (SEC-MALLS), tryptophan fluorescence, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) to identify and characterize a novel interaction between cMyBP-C and CaM. We have identified a region within the motif responsible for CaM binding and determined that the interaction is of moderate affinity, with CaM maintaining an extended conformation in the complex. We show that the interaction is Ca2+-dependent yet independent of the phosphorylation state of the motif. Our results provide the first structural evidence that cMyBP-C can access Ca2+ signaling pathways via a physical attachment to Ca2+/CaM that could have consequences for synchronizing events between cMyBP-C and its binding partners in muscle filaments.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression and Purification

The expression plasmids encoding the human cMyBP-C N-terminal constructs (C0-C1  C0C1, C1-m-C2

C0C1, C1-m-C2  C1C2, C0-C1-m-C2

C1C2, C0-C1-m-C2  C0C2, and motif

C0C2, and motif  m) were prepared as described (40). The C1C2EEE triple glutamate mutant (S275E/S284E/S304E), which incorporates a stable triphosphomimic of the motif, was isolated from a synthetic C0C2EEE gene manufactured by Genscript Inc. employing the same protocol as described for the isolation of C0, C1, and C0C1 (3). All human cMyBP-C proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta 2 cells and purified as described previously (41), whereas 15N-labeled C1C2 and the triphosphomimic C1C2EEE were produced using the procedures described previously (39). The final expressed recombinant protein included an in-frame N-terminal polyhistidine tag that was not removed due to the proteolytic sensitivity of the C1C2EEE protein. CaM and 15N-labeled CaM were expressed in E. coli Rosetta 2 cells and purified as described previously (42). Stock solutions of C1C2 and C1C2EEE were stored in a buffer containing 25 mm Tris, 350 mm NaCl, and 2 mm TCEP, pH 7.0; stock solutions of the motif were stored in buffer containing 20 mm Tris, 50 mm NaCl, 2 mm TCEP, pH 6.8; and stock solutions of CaM were stored in a buffer containing 50 mm MOPS, 150 mm NaCl, and 10 mm CaCl2, pH 7.4. The two synthetic peptides were purchased from Genscript Inc. Their sequences are RDSFRTPRDSKLEAPAEEDVWEILR and EDVWEILRQAPPSEYERIAFQYG, and they are referred to as Npep and Cpep, respectively. Prior to dialysis in titration or SAXS buffers, the lyophilized Npep or Cpep was dissolved in water and 10% acetic acid, respectively, to a final concentration of ∼4 mg/ml.

m) were prepared as described (40). The C1C2EEE triple glutamate mutant (S275E/S284E/S304E), which incorporates a stable triphosphomimic of the motif, was isolated from a synthetic C0C2EEE gene manufactured by Genscript Inc. employing the same protocol as described for the isolation of C0, C1, and C0C1 (3). All human cMyBP-C proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta 2 cells and purified as described previously (41), whereas 15N-labeled C1C2 and the triphosphomimic C1C2EEE were produced using the procedures described previously (39). The final expressed recombinant protein included an in-frame N-terminal polyhistidine tag that was not removed due to the proteolytic sensitivity of the C1C2EEE protein. CaM and 15N-labeled CaM were expressed in E. coli Rosetta 2 cells and purified as described previously (42). Stock solutions of C1C2 and C1C2EEE were stored in a buffer containing 25 mm Tris, 350 mm NaCl, and 2 mm TCEP, pH 7.0; stock solutions of the motif were stored in buffer containing 20 mm Tris, 50 mm NaCl, 2 mm TCEP, pH 6.8; and stock solutions of CaM were stored in a buffer containing 50 mm MOPS, 150 mm NaCl, and 10 mm CaCl2, pH 7.4. The two synthetic peptides were purchased from Genscript Inc. Their sequences are RDSFRTPRDSKLEAPAEEDVWEILR and EDVWEILRQAPPSEYERIAFQYG, and they are referred to as Npep and Cpep, respectively. Prior to dialysis in titration or SAXS buffers, the lyophilized Npep or Cpep was dissolved in water and 10% acetic acid, respectively, to a final concentration of ∼4 mg/ml.

CaM-agarose Pull-down Assays

CaM-agarose pull-down assays were performed to screen which of the purified C0, C0C1, C1C2, and C0C2 cMyBP-C fragments could bind CaM. Approximately 500 μl of each N-terminal fragment at 1 mg/ml in 25 mm MOPS, 50 mm KCl, 5 mm CaCl2, 2 mm TCEP, pH 7.0, was added to 100-μl aliquots of covalently linked CaM-agarose beads (Sigma) equilibrated in the same buffer. The protein/agarose bead slurries were left to incubate for ∼15 min at 4 °C, with gentle mixing every 2 min to distribute the bead matrix in solution, before being spun at 10,000 × g for 30 s to pellet the beads. The pelleted beads were sequentially resuspended/washed and spun four times using 500 μl of the aforementioned buffer to remove any unbound protein. This process was also repeated as described using a calcium-free buffer solution, where 5 mm CaCl2 was substituted by 10 mm EGTA throughout the protein binding and bead washing steps. To monitor cMyBP-C fragments binding to the CaM-agarose in the presence or absence of Ca2+, 20-μl aliquots of washed and spun beads were added to 10 μl of 25 mm Tris, pH 8.0, and 10 μl of 4× SDS-PAGE loading dye to form a 50% (v/v) bead/loading dye slurry. The slurry was subsequently boiled for 5 min and spun to repellet the beads, and 15 μl of supernatant from each individual sample was used for SDS-PAGE analysis.

Size Exclusion Chromatography with Multiple-angle Laser Light Scattering

SEC-MALLS experiments and data analyses were carried out following the procedures described previously (42). SEC-MALLS data were collected for purified Ca2+/CaM, C1C2, and a mixture of Ca2+/CaM plus [15N]C1C2 solution that contained excess Ca2+/CaM (Ca2+/CaM to [15N]C1C2 molar ratio of 2:1). Typically, ∼400 μl of protein solution at ∼100 μm was analyzed in a Superdex 75 10/30 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) coupled with the miniDAWN light scattering unit (Wyatt Technology) and a DSP refractometer (Optilab). The system was equilibrated with a standard buffer containing 25 mm MOPS, 350 mm NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2, 2 mm TCEP, pH 7.0. Unless otherwise stated, this standard buffer was used in all of the SEC-MALLS, tryptophan fluorescence, and NMR titration experiments reported in this study. Following similar conditions and procedures, SEC-MALLS data were also acquired for purified Ca2+/CaM, motif, and the Ca2+/CaM-motif complex with excess Ca2+/CaM (prepared by mixing Ca2+/CaM and motif at a 2:1 molar ratio).

Tryptophan Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Fluorescence spectra of cMyBP-C protein or peptide samples (including C1C2, C1C2EEE, motif, Cpep, and Npep) and their corresponding buffer solutions were obtained at 25 °C using a Varian Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer following the same settings as described previously (42). Prior to the titration experiments, aliquots of the cMyBP-C protein or peptide and CaM stock solutions were individually dialyzed overnight against the standard buffer. To evaluate the Ca2+ dependence of the binding, the 5 mm CaCl2 in the standard buffer was replaced by 10 mm EGTA. The effect of ionic strength on the Ca2+/CaM-C1C2 interaction was evaluated by reducing the concentration of NaCl in the standard buffer to 100 mm. Similarly, the binding of motif to Ca2+/CaM was evaluated in a buffer containing 20 mm Tris, 50 mm NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2, 2 mm TCEP, pH 6.8.

At each titration step, aliquots of a concentrated CaM solution (>1 mm) were sequentially added to the cMyBP-C protein or peptide solution (∼5 μm) and left to equilibrate for 10 min prior to recording their emission spectrum eight times. The eight spectra were averaged to produce the final spectrum. All averaged sample spectra were corrected for solvent effects by subtracting the emission spectra of the respective buffer across the full emission range. Dilution effects and the intrinsic fluorescence contribution from tyrosine were considered in the data analysis. Inner filter effects were checked for by sequentially titrating CaM stock into a standard tryptophan solution (∼40 μm). No significant inner filter effects were observed for the amount of CaM used in all titration experiments (data not shown).

To determine the binding affinity (KD) in each tryptophan fluorescence titration experiment, the relative fluorescence intensity F/F0 values (where F is the fluorescence intensity at each titration step, and F0 is the fluorescence intensity of Ca2+-free (apo-) protein or peptide) at a chosen wavelength were plotted against the concentration of CaM and fitted to a quadratic equation based on a 1:1 binding model (e.g. see Ref. 43). For the Cpep/CaM titration data, the fit to the binding curve improved significantly when a concentration adjustment factor was included in the parameters. This adjustment factor typically ranged from 0.4 to 0.8, suggesting that the peptide concentration was lower than initially estimated from the extinction coefficient at 280 nm, possibly due to the low solubility of the peptide. For each set of titration data, the wavelength that gave the largest intensity changes between the apo and bound states was chosen for analysis. To achieve this, fluorescence spectra of the apo state and the last titration point were normalized to unity using their respective maximum intensity values. Subtraction of these normalized spectra yields the wavelength at which the largest intensity changes can be observed. Note that binding affinities can also be determined by plotting the changes in maximum emission wavelength λmax (i.e. the wavelength that maximal fluorescence intensity is observed) against concentrations of CaM. The KD values determined were essentially the same using F/F0 or λmax.

NMR Spectroscopy

1H-15N HSQC spectra were recorded at 25 °C using a Bruker AVIII 800-MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance cryogenic probe. Stock protein solutions were dialyzed against the standard buffer overnight, and the final protein concentrations used in titration experiments were ∼100 μm for [15N]C1C2 and [15N]C1C2EEE and ∼130 μm for 15N-labeled Ca2+/CaM. D2O was added to each sample to a final concentration of 10% (v/v). Sodium 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate was used as the internal chemical shift reference. Spectra were processed with Topspin 2.1 (Bruker Biospin) and analyzed using SPARKY (T. D. Goddard and D. G. Kneller, University of California, San Francisco). Chemical shift assignments for [15N]C1C2, [15N]C1C2EEE, and [15N]CaM were inferred using previously published chemical shift assignments (BMRB accession number 6015 for C1, BMRB 5591 for C2, BMRB 17867 for motif, and BMRB 547 for CaM). The indole nitrogens of residues Trp196, Trp322, and Trp396 were assigned based on Ref. 44.

1H-15N HSQC spectra of [15N]C1C2 were recorded after sequential additions of unlabeled Ca2+/CaM stock solution (1.2 mm) to obtain molar ratios of [Ca2+/CaM]/[[15N]C1C2] at 0.2:1, 0.4:1, 0.8:1, 1:1, and 2:1. For each addition, the solutions were mixed and equilibrated for 10 min before spectra were recorded. Relative peak heights (using the spectrum of [15N]C1C2 alone as a reference) for all identifiable and non-overlapped residues at each titration step were plotted. Residues that underwent significant intensity changes were defined as those with peak heights decreasing by more than one S.D. value from the average. Similar NMR experiments and data analyses were carried out using [15N]C1C2EEE with molar ratios of [Ca2+/CaM]/[[15N]C1C2EEE] at 0.3:1, 0.6:1, 1:1, and 2:1.

For the reverse titrations of 15N-labeled Ca2+/CaM with unlabeled C1C2, 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled Ca2+/CaM were recorded with sequential additions of unlabeled C1C2 stock solution (∼140 μm) to obtain molar ratios of [[15N]Ca2+/CaM]/[C1C2] at 1:0.2, 1:0.3, 1:0.4, 1:0.5, 1:0.75, and 1:1. Data analyses were carried out as described except that the spectrum of 15N-labeled Ca2+/CaM was used as the reference. The experiment was repeated for 15N-labeled Ca2+/CaM (∼70 μm) and Cpep. Final molar ratios of [[15N]Ca2+/CaM]/[Cpep] used were 1:0.1, 1:0.2, 1:0.3, 1:0.4, 1:0.5, 1:0.6, 1:0.7, 1:0.85, 1:1, 1:1.5, 1:2, 1:3, and 1:4. For the Cpep titration, spectral changes presented mainly as positional rather than intensity changes; therefore, combined chemical shift perturbations (Δδppm) were calculated based on the equation, Δδppm = ((ΔδHN)2 + (0.154 × ΔδN)2)½, where ΔδHN and ΔδN represent the chemical shift variations in the proton and nitrogen dimensions, respectively. Residues with positions changed by more than one S.D. value from the mean were deemed to be significantly affected. Binding affinity was determined from fitting to a 1:1 binding model using Δδppm of residues Ala57, Val121, and Ile130 at varying concentrations of Cpep.

SAXS Data Acquisition, Analysis, and Modeling

Ca2+/CaM was freshly prepared from gel filtration in the standard buffer and immediately concentrated for SAXS measurements. For Ca2+/CaM-Cpep, the complex was prepared by simply mixing the Ca2+/CaM and Cpep solutions at a 1:3 molar ratio (note that the excess Cpep does not contribute significantly to the scattering intensity due to its small molecular volume). SAXS data were acquired at 10 °C using a SAXSess instrument (Anton Paar, Graz, Austria) with 10-mm line collimation and a charge-coupled device (CCD) detector. All data reduction and analyses followed the procedures described previously (40). Low resolution ab initio shape reconstructions were performed using the program DAMMIF (45) as described previously (41). The NSD values of each set of 10 DAMMIF models were 0.621 ± 0.012 for Ca2+/CaM and 0.557 ± 0.015 for Ca2+/CaM-Cpep, respectively.

RESULTS

cMyBP-C Fragments Containing Motif-C2 Bind to Ca2+/Calmodulin

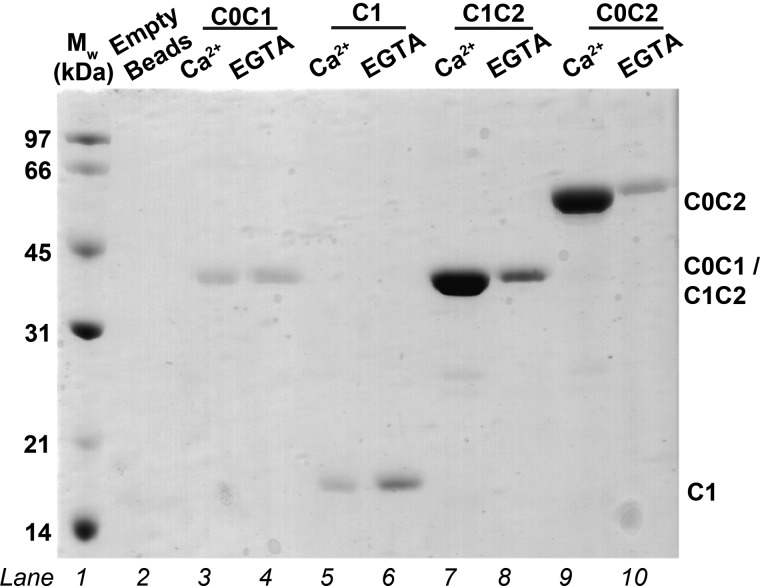

Pull-down assays were performed by incubating CaM-agarose beads with N-terminal fragments of human cMyBP-C (C0C1, C1, C1C2, and C0C2) in the presence and absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 2). Only C1C2 and C0C2, each of which includes the motif and C2, show significant binding to CaM-agarose, and this binding is Ca2+-dependent. C1C2 and C0C2 appear to be pulled down to similar extents, suggesting that C0 is not involved in the interaction and that the Ca2+/CaM binding region exists within the motif and/or C2 domain.

FIGURE 2.

SDS-PAGE pull-down assays indicating interactions between different cMyBP-C N-terminal fragments and CaM. The effects of Ca2+ on the interactions are tested by comparing results obtained in the presence of Ca2+ or with EGTA. Samples in lanes from left to right are as follows. Lane 1, molecular weight (Mw) standards; lane 2, CaM-agarose beads only; lanes 3 and 4, C0C1 + CaM-agarose; lanes 5 and 6, C1 + CaM-agarose; lanes 7 and 8, C1C2 + CaM-agarose; lanes 9 and 10, C0C2 + CaM-agarose. For each of the paired lanes (lanes 3 and 4, 5 and 6, 7 and 8, and 9 and 10), the left lane is with Ca2+, and the right is with EGTA. The calculated molecular masses for C0C2, C0C1, C1C2, and C1 are 49, 27, 33, and 11 kDa, respectively, based on their amino acid sequences. C0C1 and C1 both consistently migrate at “larger than expected” molecular masses.

Based on the qualitative pull-down assessments, a solution containing C1C2 and Ca2+/CaM in molar excess was subjected to SEC-MALLS. The results indicate that the first and predominant peak eluting from the column corresponds to a species with an experimental molecular mass of 48.9 ± 0.2 kDa, consistent with the theoretical molecular mass of 52 kDa for a 1:1 Ca2+/CaM-C1C2 complex, whereas a second elution peak corresponds to excess Ca2+/CaM (data not shown).

Tryptophan fluorescence was then used to confirm and further characterize the binding between C1C2 and Ca2+/CaM. CaM-binding proteins commonly have a tryptophan in their CaM recognition sequences (6, 9), which makes tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy useful for probing CaM interactions, especially because CaM itself contains no tryptophans. There are four tryptophans in C1C2: Trp191, Trp196, Trp322, and Trp396. Based on the NMR and crystal structures of the C1 and C2 domains (44, 46, 47), there is one tryptophan located in the central hydrophobic core of each of the C1 and C2 domains (Trp191 and Trp396, respectively), Trp196 is located on the outer surface of the C1 domain, and forms part of the β-barrel, and Trp322 resides within the motif (Fig. 1B).

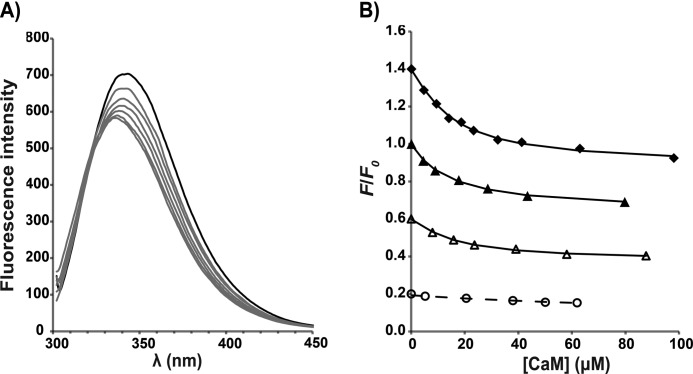

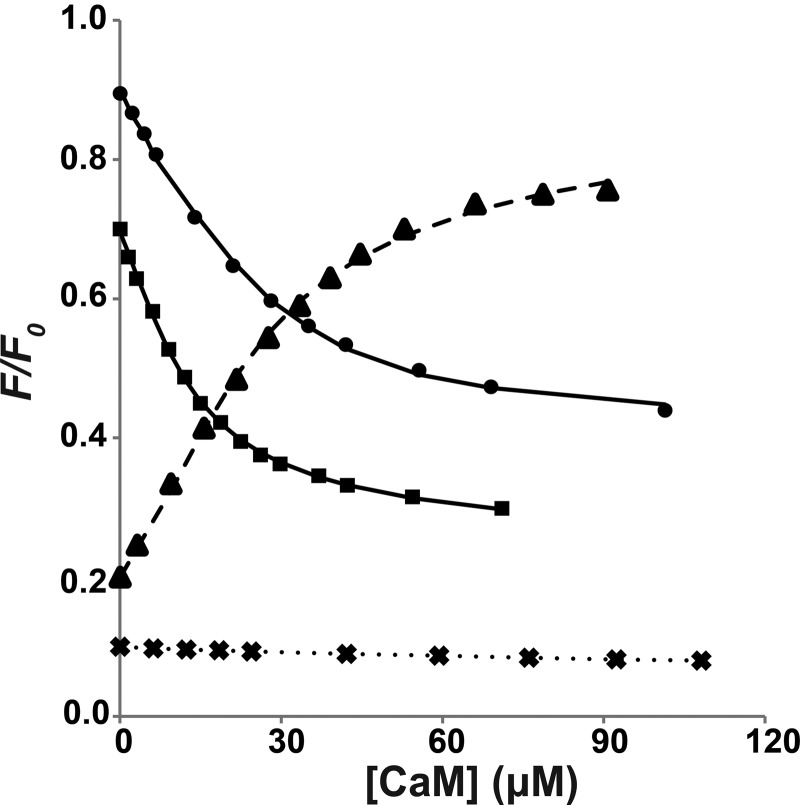

As Ca2+/CaM was titrated into a C1C2 solution, a shift of the tryptophan emission peak was observed, with the maximum emission wavelength λmax changing from ∼345 to ∼336 nm; the blue shift is accompanied by a decrease in the maximum fluorescence intensity (Fig. 3). Tryptophan quenching is dominated by its carbonyl group and is very sensitive to changes in its local environment (48, 49). The observed changes in λmax and intensity therefore indicate that the chemical environment of one or more of the tryptophans in C1C2 is altered upon Ca2+/CaM binding. Relative intensity changes at the wavelength giving the maximum change could be fitted to a 1:1 binding model to yield a dissociation constant (KD) of 13.5 ± 2.5 μm (Table 1). As in the pull-down assay, this interaction is Ca2+-dependent, and the binding affinity reduces markedly in the presence of EGTA (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Further, unlike other reported CaM-peptide interactions (6, 9), the affinity of the Ca2+/CaM-C1C2 interaction appears to be independent of ionic strength up to NaCl concentrations of 350 mm (Fig. 3 and Table 1).

FIGURE 3.

Tryptophan fluorescence from the cMyBP-C N-terminal fragments C1C2 and C1C2EEE titrated with Ca2+/CaM. A, fluorescence emission spectra for the titration of C1C2 with CaM in the standard buffer and in the presence of Ca2+. A blue shift of the maximum emission wavelength is accompanied by a decrease in the maximum fluorescence intensity. The black line corresponds to the spectrum of the free protein before adding Ca2+/CaM, and the gray lines represent spectra from the sequential titration points. B, determination of binding affinities (KD) from different titration experiments. For each titration data set, the symbols represent the experimental data of the fluorescence intensity at each titration step (F) relative to the fluorescence in the absence of Ca2+/CaM (F0) at a chosen wavelength. The lines are fitted curves for determination of KD based on a 1:1 model. For clarity of representation, each titration data set has been scaled by multiplying with the following constants in the (F/F0) values: C1C2EEE, 1.4 (♦); C1C2, 1.0 (▴); C1C2 in 100 mm NaCl, 0.6 (△); and C1C2 in EGTA, 0.2 (○). Each data point is the average of eight replicate measurements after correcting for solvent; the error bars (not shown; corresponding to ±1 S.D.) are smaller than the symbols. Note that “C1C2 in 100 mm NaCl” data were acquired in buffer containing 100 mm NaCl, and “C1C2 in EGTA” data were acquired in buffer containing 10 mm EGTA; the rest of the titrations were performed in the standard buffer containing 350 mm NaCl (for details, see “Experimental Procedures”).

TABLE 1.

Binding affinities (KD) of cMyBP-C protein or peptide binding to Ca2+-CaM determined from tryptophan fluorescence experiments

Unless otherwise stated, a standard buffer containing 25 mm MOPS, 350 mm NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2, 2 mm TCEP, pH 7.0, was used. R2 values describe the goodness of fit of titration data, with R2 of 1 indicating that the experimental values match exactly with the predicted values using a 1:1 model.

| C1C2 | C1C2 (in 100 mm NaCl) | C1C2 (in EGTA) | C1C2EEE | Motif | Motif (in 50 mm NaCl) | Cpep | Npep | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KD ± S.D. (μm) | 13.5 ± 2.5 | 8.7 ± 3.0 | >120 | 6.6 ± 1.7 | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 1.3 | >400 |

| R2 | 0.998 | 0.996 | 0.994 | 0.994 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.999 |

C1C2 Binds Ca2+/CaM Primarily via the Motif

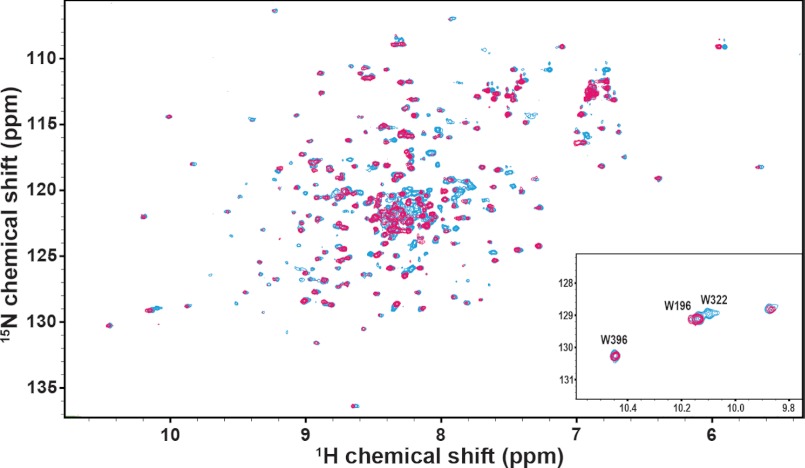

NMR experiments were carried out to further characterize the interaction between C1C2 and Ca2+/CaM. 1H-15N HSQC spectra were recorded for 15N-labeled C1C2 titrated with unlabeled Ca2+/CaM to a final molar ratio of 1:2 for [[15N]C1C2]/[Ca2+/CaM]. The 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of [15N]C1C2 is of high quality (Fig. 4) and shows mainly sharp and well dispersed peaks similar to the [15N]C1C2 spectrum reported by Ababou et al. (44). These peaks overlay well with assignments reported for the isolated C1 and C2 domains (BMRB accession numbers 6105 and 5591) and indicate that the C1 and C2 Ig modules in C1C2 adopt the same fold as the individual domains (44, 46). Over ∼80% of the amide resonances of C1 and C2 in [15N]C1C2 could be inferred readily from the reported assignments. In contrast, the motif contributes to a substantial proportion of the unidentified peaks in the [15N]C1C2 spectrum with 1H chemical shifts between 8 and 9 ppm typical of disordered regions. Recently, Howarth et al. (50) reported NMR results showing that residues 315–351 of the 103-residue mouse motif form a small three-helical bundle (Fig. 1B), whereas the remainder of the motif is unstructured. The mouse cMyBP-C motif shares ∼89% sequence identity with the human isoform (Fig. 1C), with only one amino acid difference in the three-helical bundle (Tyr340 for human versus His336 for mouse). However, despite the high degree of sequence similarity, only ∼30% of amide assignments from the small three-helical bundle of the mouse motif (BMRB accession number 17867) could be confidently matched to corresponding peaks in our [15N]C1C2 spectrum due to spectral overlap, especially in the region of the spectrum dominated by disordered structures.

FIGURE 4.

[15N]C1C2 NMR titration with Ca2+/CaM. Overlay of 15N HSQC spectra of human C1C2 before (cyan) and after the addition of Ca2+/CaM (magenta) at a molar ratio of 1:1 ([[15N]C1C2]/[Ca2+/CaM]). Inset, chemical shift changes of indole resonances of Trp196, Trp322, and Trp396.

Upon the addition of Ca2+/CaM to [15N]C1C2, a subset of peaks in the 15N-1H HSQC NMR spectrum displayed a severe drop in signal intensity, with some peaks disappearing completely (Fig. 4). Specifically, ∼66% of the amide resonance peaks mapped to the structured region of the motif showed significant intensity changes upon binding to Ca2+/CaM, including those assigned to Ala317, Ile324, Arg326, Ala328, Tyr333, Glu334, Arg346, Lys350, and Arg351 that disappeared completely. In contrast, only a handful of peaks mapped to C1 and C2 were affected. In addition, a large proportion of peaks in the disordered region, which are likely to correspond to the unstructured residues within the motif, disappeared during the titration. Even at the highest concentration of Ca2+/CaM titrated, no new peaks are observed, suggesting peaks corresponding to the bound state are broadened beyond detection, possibly due to the large size of the complex (∼52 kDa) and/or conformational exchanges on the intermediate NMR time scale.

The indole resonances of the four tryptophans in [15N]C1C2 are among the set of residues that can be identified based on previously reported assignments (44). Interestingly, the indole peak for Trp322 in the motif disappears at the first addition of Ca2+/CaM (Fig. 4, inset), suggesting that the environment of this tryptophan is very sensitive to the formation of the Ca2+/CaM-C1C2 complex, whereas the remaining three tryptophan indole peaks of [15N]C1C2 (i.e. Trp191, Trp196, and Trp396 from the C1 and C2 Ig modules) remain essentially unaffected throughout the course of the titrations.

The C-terminal End of the Motif Alone Is Sufficient for Binding to Ca2+/CaM

NMR titration studies suggest that the motif is predominantly responsible for the binding to Ca2+/CaM, with C1 and C2 playing only a minor role if any. Therefore, tryptophan fluorescence experiments were performed with a construct that encodes for the human motif only. Again, the characteristic blue shift and intensity decrease in the fluorescence emission spectra were observed as for C1C2 (Fig. 5), suggesting that the change in chemical environment of Trp322 upon binding Ca2+/CaM is similar. The affinity of the interaction is also comparable between Ca2+/CaM-motif and Ca2+/CaM-C1C2 (Table 1). In addition, the binding stoichiometry remains the same at 1:1 according to SEC-MALLS analysis (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Affinities (KD) of cMyBP-C motif and peptides binding to Ca2+/CaM determined from tryptophan fluorescence experiments. For each titration data set, the data points and fitted curves were obtained using the same approaches described in Fig. 3. For clarity of representation, each titration data set has been scaled by multiplying the following constants in the (F/F0) values: motif, 0.9 (●); motif in 50 mm NaCl, 0.7 (■); Cpep, 0.2 (▴); and Npep, 0.1 (×). Each data point is the average of eight replicate measurements after correcting for solvent; the error bars (not shown; corresponding to ± 1 S.D.) are smaller than the symbols. All titrations were performed in the standard buffer except for “motif in 50 mm NaCl” data, which used a reduced NaCl concentration (see details under “Experimental Procedures”).

The majority of the CaM minimal binding sequences characterized to date are 16–30 residues in length (9, 51, 52), with two large hydrophobic residues positioned to interact with the two CaM lobes. Hence, we considered whether the minimum binding region in cMyBP-C could be substantially shorter than the 97-residue motif. Because our fluorescence and NMR results suggest that Trp322 is likely to be critical for anchoring Ca2+/CaM, two peptides containing Trp322 and at least one candidate for a second hydrophobic anchor were tested for binding Ca2+/CaM using tryptophan fluorescence. The sequences selected were an 18-residue peptide from the sequence mainly upstream of Trp322 (Arg309–Lys326, termed Npep) and an alternate 23-residue peptide from the sequence mainly downstream of Trp322 (Glu319–Lys341, termed Cpep) (Fig. 1C). Significantly, Cpep binds to Ca2+/CaM with an affinity (i.e. 4.3 ± 1.3 μm) comparable with that of the motif, whereas Npep displays negligible binding (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Therefore, Cpep appears to contain most or all of the amino acid sequence that is important for the Ca2+/CaM interaction.

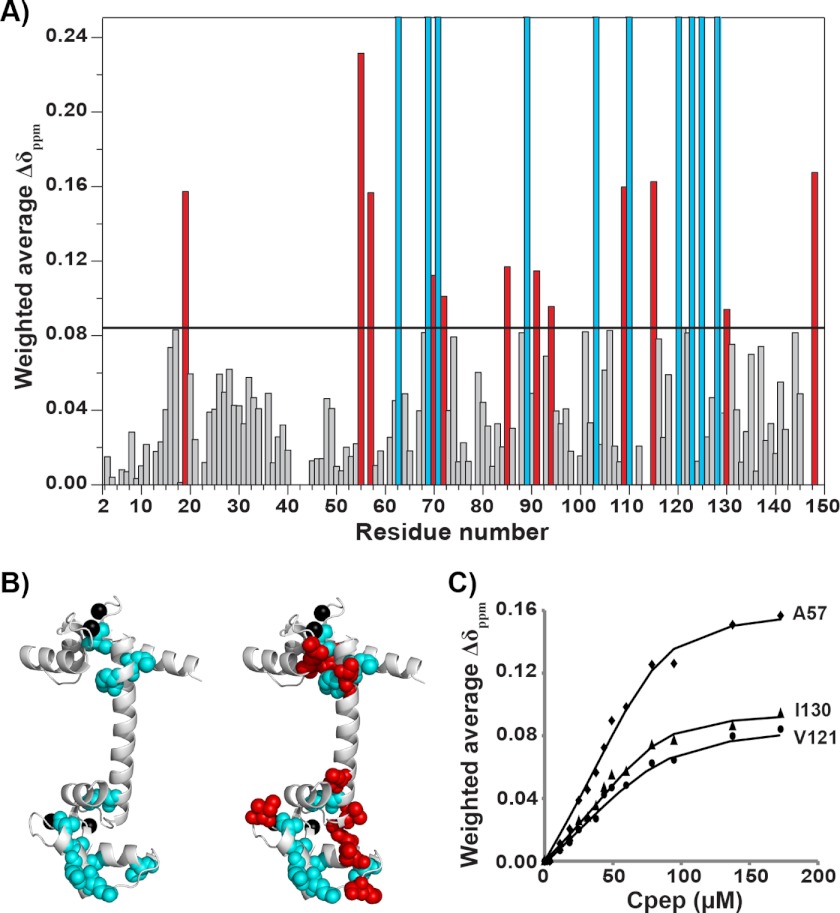

Ca2+/CaM Binds to Cpep via the Hydrophobic Cleft in Each Ca2+-binding Lobe

In order to probe which residues in Ca2+/CaM are responsible for binding Cpep, 15N HSQC spectra were recorded as Cpep was titrated into 15N-labeled Ca2+/CaM. The 15N HSQC spectrum from Ca2+/CaM alone overlays well with previously reported assignments (BMRB accession number 547), and ∼77% of the amide resonances could be readily inferred from the reported assignments, with another 12% of peaks tentatively mapped.

As Cpep was titrated into 15N-labeled Ca2+/CaM, many peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum moved, and a small subset of peaks disappeared, consistent with fast- and slow-intermediate exchange on the NMR time scale, respectively. A similar number of signals that had disappeared were observed to reappear at a molar ratio of ∼1:4 (Ca2+/CaM to Cpep) (data not shown). The residues in CaM that undergo the largest chemical shift changes (corresponding to peaks that disappeared; Fig. 6A) include Ile63, Leu69, Met71, Phe89, Ala103, Thr110, Glu120, Glu123, Ile125, and Ala128, whereas significantly perturbed residues (defined as moving by more than one S.D. from the mean) include Phe19, Val55, Ala57, Thr70, Met72, Ile85, Val91, Lys94, Arg106, Met109, Lys115, Ile130, and Lys148. Interestingly, when these residues are mapped onto the crystal structure of Ca2+/CaM (53), they are all located in the hydrophobic clefts of the two Ca2+-binding lobes of Ca2+/CaM (Fig. 6B) with ∼70% of affected peaks arising from the C-terminal lobe. In contrast, resonance peaks belonging to the interconnecting central helix (residues 73–84) show little perturbation even at the highest concentration of Cpep.

FIGURE 6.

Cpep-binding interfaces of Ca2+/CaM. A, weighted chemical shift changes Δδppm (HN, H) for assigned residues of 15N-labeled Ca2+/CaM following the addition of Cpep at a molar ratio of 4:1 (Cpep/[15N]CaM). The horizontal line indicates 1 S.D. above the mean chemical shift change. Red bars correspond to residues deemed to have undergone significant chemical shift changes (>1 S.D.). Cyan bars correspond to residues that underwent even larger chemical shift changes but could not be traced during the titration or did not reappear in the spectrum. B, annotated structure of Ca2+/CaM (PDB 1CCL) showing the locations of the perturbed residues as identified in A. Residues corresponding to cyan bars and red bars in A are shown as cyan and red spheres, respectively. Bound calcium atoms are shown as black spheres. For clarity, the left panel highlights only the cyan spheres, and the right panel highlights both cyan and red spheres. C, examples of the fitted binding curves for residues in fast exchange, including Ala57, Val121, and Ile130 (see Table 2 for corresponding KD values).

It has been reported previously that the C-lobe of Ca2+/CaM commonly acts as the initial recognition site and binds more tightly than the N-lobe in other CaM-peptide and CaM-protein interactions (6, 9). To calculate the affinity of each Ca2+-binding lobe for Cpep, binding curves were constructed by following the migration of fast exchange peaks from each lobe. The peak position changes were fitted to a 1:1 binding model by nonlinear least squares regression (for examples, see Fig. 6C). In summary, all but one of the N-lobe residues examined gave dissociation constants in the range of ∼24–60 μm, whereas all C-lobe residues gave dissociation constants of ∼5–10 μm (Table 2), suggesting that the C-lobe does bind Cpep slightly more tightly than the N-lobe. The relatively large variations in the fitted dissociation constants and the associated errors probably reflect that the exchange regime is not strictly fast (but rather fast-intermediate), leading to errors with peak position determination. Nonetheless, the overall binding affinity for the C-terminal lobe as determined by NMR is consistent with binding affinities determined from the tryptophan fluorescence experiments (Table 1).

TABLE 2.

Binding affinities (KD) of residues that underwent signal fast exchange during the titration of 15N-labeled Ca2+/CaM with Cpep

R2 values describe the goodness of fit of titration data with R2 of 1, indicating that the experimental values matched with the predicted values using a 1:1 model.

| Phe16 | Val55 | Ala57 | Thr70 | Arg74 | Lys115 | Leu116 | Val121 | Ile130 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KD ± S.D. (μm) | 47.3 ± 8.1 | 59.2 ± 16.2 | 4.9 ± 2.3 | 28.4 ± 9.6 | 24.4 ± 5.6 | 9.3 ± 5.2 | 5.3 ± 2.3 | 9.4 ± 4.4 | 4.6 ± 2.2 |

| R2 | 0.997 | 0.994 | 0.990 | 0.990 | 0.995 | 0.983 | 0.990 | 0.986 | 0.990 |

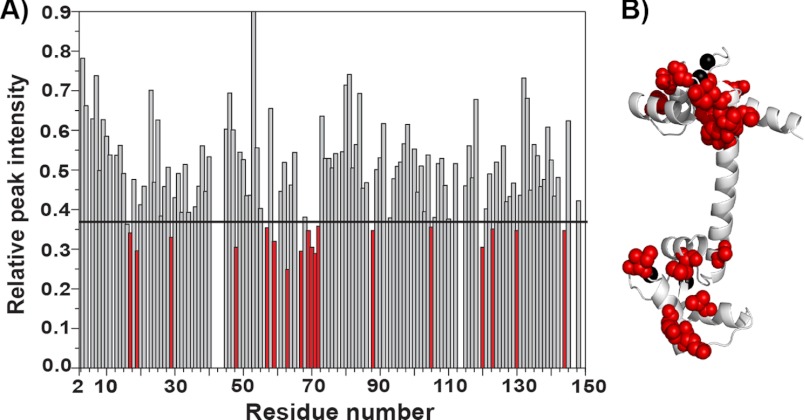

To confirm that the binding mode of Ca2+/CaM is conserved between its interaction with Cpep and in the context of cMyBP-C, the 15N HSQC titration experiment was also carried out using the larger construct C1C2. Upon the addition of C1C2 to 15N-labeled Ca2+/CaM, many peaks in the 15N HSQC spectrum experienced a severe drop in signal intensity and disappeared (Fig. 7A). The 15 amide resonance peaks that were deemed to have experienced significant intensity changes (namely Ser17, Phe19, Thr29, Leu48, Ala57, Gly59, Ile63, Glu67, Leu69, Thr70, Met71, Met72, Ala88, Leu105, Glu120, Glu123, Ile130, and Met144) when bound to C1C2 again mapped specifically to the hydrophobic clefts in each of the two lobes of CaM, similar to the result for Cpep (Fig. 7B). Therefore, the binding mode is likely to be conserved between Cpep and C1C2.

FIGURE 7.

15N-Labeled Ca2+/CaM NMR titration with C1C2. A, graph showing relative changes in peak intensity for assigned 15N-labeled Ca2+/CaM residues upon the addition of C1C2 at a molar ratio of 0.2:1 (C1C2 to 15N-labeled Ca2+/CaM). The horizontal line indicates 1 S.D. above the mean intensity change. Red bars correspond to residues that were deemed to have undergone significant intensity changes (>1 S.D.). B, annotated structure of Ca2+/CaM (PDB 1CLL) showing that residues that undergo significant intensity changes (>1 S.D.) upon C1C2 binding are located in the N- and C-terminal lobes (shown as red spheres). Bound calcium atoms are shown as black spheres.

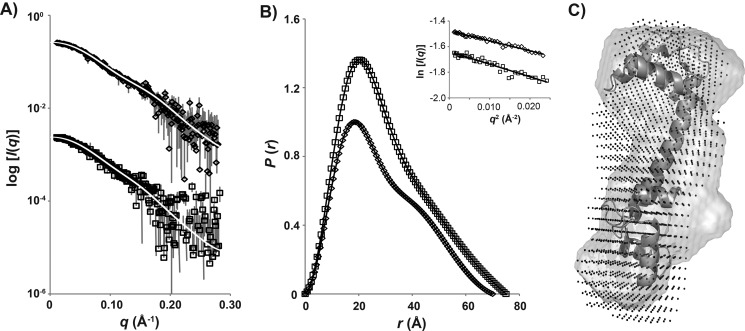

Ca2+/CaM Has an Extended Conformation in Its Complex with Cpep

SAXS was used to determine the solution conformation of the Ca2+/CaM-Cpep complex. The scattering profiles of Ca2+/CaM and its complex with Cpep are shown in Fig. 8A, and the associated structural parameters are summarized in Table 3. Guinier plots for Ca2+/CaM and Ca2+/CaM-Cpep (Fig. 8B, inset) are linear, consistent with the proteins in solution being predominantly monodisperse. AutoPorod (54) calculations yield volumes consistent with the expected molecular mass based on amino acid content. The probable distribution of distances between atom pairs (P(r) profiles calculated using GNOM (55); Fig. 8B) yields forward scattering intensity (I(0)) and radius of gyration (Rg) values in good agreement with those determined from the Guinier plots as well as the maximum linear dimension Dmax for the scattering particles. The structural parameters of Ca2+/CaM (Rg = 22.3 Å, Dmax = 70 Å) agree reasonably with previously reported values (42, 56, 57) except that the Rg value is ∼1 Å (i.e. 5%) larger, probably due to the high salt concentrations in these samples. The Ca2+/CaM-Cpep complex has Rg and Dmax values of 23.3 and 75 Å, respectively, each slightly larger than those for the unbound Ca2+/CaM. Thus, unlike the classical short helical peptides that bind CaM, there is no conformational collapse of CaM upon binding Cpep. Consistent with this, the P(r) profile of Ca2+/CaM-Cpep is similar in shape to that for CaM alone, although with a less pronounced shoulder at r ∼45 Å (Fig. 8B) that is probably accounted for by the fact that the peptide occupies space that results in less of a “dumbbell” shape compared with CaM alone. Ab initio shape reconstructions (Fig. 8C) also show that Ca2+/CaM-Cpep is similarly extended as the unbound Ca2+/CaM with the extra mass evident that can be attributed to the bound Cpep. The scattering data are thus consistent with the NMR results indicating that Cpep interacts with both lobes of Ca2+/CaM.

FIGURE 8.

SAXS profiles of Ca2+/CaM and Ca2+/CaM-Cpep complex. A, SAXS data as I(q) versus q for Ca2+/CaM (♢) and the Ca2+/CaM-Cpep complex (□) with the GNOM fits (white lines) superposed. The measured data were all placed on an absolute scale using scattering from water but are shown here multiplied on the I(q) axis for clarity. B, P(r) versus r calculated using the data in A and normalized to the ratio of the square of the molecular mass of each protein. The symbols are as for A, and error bars (not shown; corresponding to ± 1 S.D.) are smaller than the symbols. Inset, Guinier plots of the SAXS data for Ca2+/CaM (♢) and Ca2+/CaM-Cpep complex (□) and linear fits (line) to the data at qRg < 1.3. C, shape reconstructions of Ca2+/CaM and Ca2+/CaM-Cpep overlaid with the crystal structure of Ca2+/CaM. Crystal structure of Ca2+/CaM (PDB 1CLL) is shown in a ribbon diagram, and shape reconstructions of Ca2+/CaM alone and Ca2+/CaM-Cpep are shown as a gray surface and in black dots, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Structural parameters for CaM and Ca2+/CaM-Cpep complex

| Ca2+/CaM | Ca2+/CaM-Cpep | |

|---|---|---|

| Structural parameters | ||

| I(0) (cm−1) (from P(r)) | 0.0524 ± 0.0006 | 0.0477 ± 0.0004 |

| Rg (Å) (from P(r)) | 22.3 ± 0. 3 | 23.2 ± 0.2 |

| I(0) (cm−1) (from Guinier) | 0.0522 ± 0.0004 | 0.0474 ± 0.0005 |

| Rg (Å) (from Guinier) | 21.7 ± 0.5 | 23.0 ± 0.3 |

| Dmax (Å) | 70 | 75 |

| Mr estimates | ||

| Partial specific volume (cm3·g−1) | 0.723 | 0.728 |

| Contrast (Δρ × 1010 cm−2) | 2.978 | 2.962 |

| Concentration from A280 nm (mg·ml−1) | 4.3 | 2.3 |

| Mr from I(0) | 15,509 (7%) | 26,247 (34%)a |

| Mr from AutoPorod | 15,620 (6%) | 19,567 (0%) |

| Mr DAMMIF volume/2 | 17,000 (2%) | 21,700 (11%) |

| Calculated monomeric Mr from sequence | 16,700 | 19,500 |

a The relatively large error in Mr determined from I(0) is due to the low solubility of Cpep.

It is well documented for Ca2+/CaM that whereas the two hydrophobic lobes are folded into globular domains, the central helix contains a flexible region (residues 77–81) that facilitates the two lobes binding peptide sequences of different lengths and composition (6, 9). Kratky plots of Ca2+/CaM and Ca2+/CaM-Cpep complex are consistent with largely folded globular proteins with some flexibility (data not shown). It appears that this flexibility is retained to a similar degree in the Ca2+/CaM-Cpep complex as in Ca2+/CaM alone, consistent with the NMR titration experiments with 15N-labeled Ca2+/CaM-Cpep showing that residues within the central helix do not experience large chemical shift changes when the two lobes bind to Cpep.

The Interaction between Ca2+/CaM and Motif Is Phosphorylation-independent

Typically C1C2 is unphosphorylated following expression in bacteria (58). To determine the specific role of the phosphorylation-induced change in charge, we generated a mutant that is a triphosphomimic, C1C2EEE, by substituting glutamate (E) for serine (S) at the CaMKII (S284E) and PKA phosphorylation sites (S275E and S304E) of human C1C2 (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, C1C2EEE binds to Ca2+/CaM in a very similar fashion and with an affinity comparable with that of the wild-type C1C2 as monitored by tryptophan fluorescence (Fig. 3 and Table 1). The 1H-15N HSQC spectra of [15N]C1C2EEE and [15N]C1C2 overlay very well (data not shown) with few differences, which are located mainly in the region associated with disordered structure and probably corresponded to residues in close proximity to the three Ser to Glu mutations. It appears that these mutations do not induce large conformational changes in the C1 and C2 domains or in the motif. In particular, the indole resonances of [15N]C1C2EEE overlay well with those of [15N]C1C2, suggesting that the chemical environment around the four tryptophan residues (including Trp322 in the motif) remain the same in C1C2EEE as in C1C2. Consistent with results from tryptophan fluorescence experiments, 1H-15N HSQC spectra of [15N]C1C2EEE titrated with unlabeled Ca2+/CaM show patterns of resonance intensity changes similar to those of [15N]C1C2, confirming that [15N]C1C2EEE interacts with Ca2+/CaM similarly to [15N]C1C2 (data not shown) with Trp322 in the motif of [15N]C1C2EEE also directly interacting with Ca2+/CaM.

DISCUSSION

By combining pull-down assays, SEC-MALLS, tryptophan fluorescence, and NMR titration data, we have identified a novel interaction between the N-terminal fragment C1C2 of human cMyBP-C and CaM. Previous co-sedimentation assays have failed to detect this interaction (59). The 1:1 stoichiometric interaction is Ca2+-dependent and independent of ionic strength. Furthermore, we conclude that the motif that links the C1 and C2 modules is required for the complex formation and that a 23-residue sequence (i.e. residues Glu319–Lys341) at the C-terminal end of the motif is sufficient for maintaining this interaction. This 23-residue peptide (Cpep) has no obvious consensus with any reported CaM-target sequences identified to date (5, 6, 51). Nevertheless, the formation of a Ca2+/CaM-C1C2 complex appears to be specific because NMR titration data confirm that a number of hydrophobic residues from both motif and Ca2+/CaM are involved in the complex formation. The interaction of Ca2+/CaM with the motif is via the hydrophobic clefts within the two Ca2+-binding lobes of CaM, as has been observed in all CaM-target complexes (5, 6, 9), and as is commonly observed the C-lobe of CaM appears to interact slightly more strongly with the motif than the N-lobe does. In addition, our results show that basic residues and methionine residues of 15N-labeled Ca2+/CaM are among the residues that undergo large chemical shift changes during titrations with Cpep, indicating that these residues are important for the complex formation, again consistent with previous suggestions that they act to optimize the contacts between CaM and the hydrophobic interface of its target protein (6, 9). It is likely that the tryptophan residue (Trp322) within the motif is involved in anchoring to Ca2+/CaM, similar to what has been observed in other known CaM-target peptides (6, 9–14). It is noteworthy that residue Trp322, together with most of the residues included in the 23-residue Cpep sequence, is highly conserved between isoforms and species of myosin-binding protein C (19, 24), arguing that its ability to bind to Ca2+/CaM could be a crucial function of the protein. Consistent with this idea, seven mutations linked to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy have been identified in the gene encoding this 23-residue sequence (including single amino acid substitutions, such as R326Q, E334K, V342D, and L352P, and frameshift mutations at positions, such as Gln327, Thr343, and Met348) (60).

In the context of CaM-binding sequences commonly being helical, it is interesting that the equivalent Cpep sequence forms two short α-helices within a three-helical bundle in the mouse motif structure (50) (Fig. 1B). In this configuration, residue Trp322 lies within the hydrophobic core of the three-helical bundle, whereas for the shorter Cpep that does not include the third helix, Trp322 is likely to be more solvent-exposed. Consistent with this idea, the tryptophan fluorescence intensity increases for Cpep as it binds to Ca2+/CaM, whereas intensity decreases are observed for all constructs containing an intact motif upon binding (Figs. 3 and 5). Unlike the classic collapsed conformations of CaM observed when binding short helical target sequences (6, 9), the SAXS data show that Cpep binds to an extended Ca2+/CaM. Of note, the maximum length of the two helices of Cpep (∼38 Å) is sufficient to span the two Ca2+-binding lobes of CaM in its extended formation. Taken together, our data suggest that CaM probably induces conformational changes within the structured three-helical bundle of the motif to expose and position Trp322 for binding; one way this could be achieved is through hinge motions at the junctions connecting the helices.

At Ca2+ concentrations below the threshold for muscle contraction, Ca2+-regulated changes in phosphorylation of cMyBP-C are related to changes in cardiac contractility (28). Activation of CaMKII requires Ca2+/CaM for autophosphorylation prior to its phosphorylating Ser282 in the motif (19, 61). Thus, the Ca2+-dependent interaction between the motif and CaM may be functionally important to the timing and sequence of phosphorylation events that regulate cMyBP-C attachment and detachment from myosin ΔS2. Interestingly, the interaction reported here is independent of the phosphorylation state of the motif because both C1C2 and the triphosphomimic C1C2EEE bind to Ca2+/CaM with micromolar affinity. C1C2 (predominantly via the motif) has also been found to bind to myosin ΔS2 with a KD of ∼5 μm (24), which is comparable with its binding affinity with Ca2+/CaM as identified in this study. However, the interaction between C1C2 and myosin ΔS2 can be abolished by phosphorylation of the motif (23). Therefore, the motif appears to interact with Ca2+/CaM in a region structurally independent from the three phosphorylation sites so that phosphorylation or mutation of these sites has no impact on its interaction with Ca2+/CaM. Consistent with this idea, we have identified residues involved in direct interactions with Ca2+/CaM clustered at the structured C-terminal end of the motif.

In light of the fact that Ca2+/CaM binds to the motif independently of its apparent phosphorylation state, it is interesting to consider the idea that this interaction could provide a means to store and readily supply Ca2+/CaM. For example, CaMKII requires Ca2+/CaM to initiate the first phosphorylation event necessary for additional phosphorylation events in the motif. Alternatively, when C1C2 is bound to myosin ΔS2, the bound Ca2+/CaM on the motif may also facilitate phosphorylation of neighboring myosin RLC via the Ca2+/CaM-dependent MLCK to promote myosin cross-bridge formation (34, 62). The micromolar range binding affinity between motif and Ca2+/CaM is weaker than affinities reported for most CaM-target proteins (KD values between 0.1 μm and 0.01 nm) (6, 52); therefore, these CaM-regulated proteins, in particular CaMKII and MLCK, which are responsible for modulating contractile events, could compete with the motif for Ca2+/CaM. Upon autophosphorylation of CaMKII or MLCK, CaM would be released and bind to the motif of cMyBP-C for storage.

The role of the interaction between Ca2+/CaM and the motif of cMyBP-C reported in this study has yet to be fully understood in the context of the complex molecular networks that regulate muscle contraction. Nonetheless, our observations provide the first evidence that CaM can link cMyBP-C with the Ca2+ signaling pathways in muscle, which opens the possibility of the interaction playing a role in synchronizing key regulatory phosphorylation events.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Paul Rosevear for providing the mouse motif assignments.

This work was supported by Australian Research Council Grant DP120103841.

- CaMKII

- Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- CaM

- calmodulin

- MyBP-C

- myosin-binding protein C

- cMyBP-C

- cardiac MyBP-C

- myosin ΔS2

- the 126 residues of human cardiac β-MHC (residues 848–963)

- MLCK

- myosin light chain kinase

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- RLC

- myosin regulatory light chain

- SAXS

- small angle x-ray scattering

- SEC-MALLS

- size exclusion chromatography coupled with multiple-angle laser light scattering

- TCEP

- tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- TnC and TnI

- troponin C and I, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1. Geeves M. A., Holmes K. C. (2005) The molecular mechanism of muscle contraction. Adv. Protein. Chem. 71, 161–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whitten A. E., Jeffries C. M., Harris S. P., Trewhella J. (2008) Cardiac myosin-binding protein C decorates F-actin. Implications for cardiac function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 18360–18365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Orlova A., Galkin V. E., Jeffries C. M., Egelman E. H., Trewhella J. (2011) The N-terminal domains of myosin-binding protein C can bind polymorphically to F-actin. J. Mol. Biol. 412, 379–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chin D., Means A. R. (2000) Calmodulin. A prototypical calcium sensor. Trends Cell Biol. 10, 322–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vetter S. W., Leclerc E. (2003) Novel aspects of calmodulin target recognition and activation. Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 404–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crivici A., Ikura M. (1995) Molecular and structural basis of target recognition by calmodulin. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 24, 85–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hartzell H. C., Glass D. B. (1984) Phosphorylation of purified cardiac muscle C-protein by purified cAMP-dependent and endogenous Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 15587–15596 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schlender K. K., Bean L. J. (1991) Phosphorylation of chicken cardiac C-protein by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 2811–2817 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yamniuk A. P., Vogel H. J. (2004) Calmodulin's flexibility allows for promiscuity in its interactions with target proteins and peptides. Mol. Biotechnol. 27, 33–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rodríguez-Castañeda F., Maestre-Martínez M., Coudevylle N., Dimova K., Junge H., Lipstein N., Lee D., Becker S., Brose N., Jahn O., Carlomagno T., Griesinger C. (2010) Modular architecture of Munc13/calmodulin complexes. Dual regulation by Ca2+ and possible function in short-term synaptic plasticity. EMBO J. 29, 680–691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim E. Y., Rumpf C. H., Van Petegem F., Arant R. J., Findeisen F., Cooley E. S., Isacoff E. Y., Minor D. L., Jr. (2010) Multiple C-terminal tail Ca2+/CaMs regulate CaV1.2 function but do not mediate channel dimerization. EMBO J. 29, 3924–3938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Köster S., Pavkov-Keller T., Kühlbrandt W., Yildiz Ö. (2011) Structure of human Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1 regulatory region in complex with calmodulin and Ca2+. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 40954–40961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Izumi Y., Watanabe H., Watanabe N., Aoyama A., Jinbo Y., Hayashi N. (2008) Solution x-ray scattering reveals a novel structure of calmodulin complexed with a binding domain peptide from the HIV-1 matrix protein p17. Biochemistry 47, 7158–7166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schumacher M. A., Rivard A. F., Bächinger H. P., Adelman J. P. (2001) Structure of the gating domain of a Ca2+-activated K+ channel complexed with Ca2+/calmodulin. Nature 410, 1120–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lu Y., Jeffries C. M., Trewhella J. (2011) Invited review. Probing the structures of muscle regulatory proteins using small-angle solution scattering. Biopolymers 95, 505–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oakley C. E., Hambly B. D., Curmi P. M., Brown L. J. (2004) Myosin-binding protein C. Structural abnormalities in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Cell Res. 14, 95–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oakley C. E., Chamoun J., Brown L. J., Hambly B. D. (2007) Myosin-binding protein-C. Enigmatic regulator of cardiac contraction. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39, 2161–2166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Flashman E., Redwood C., Moolman-Smook J., Watkins H. (2004) Cardiac myosin-binding protein C. Its role in physiology and disease. Circ. Res. 94, 1279–1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gautel M., Zuffardi O., Freiburg A., Labeit S. (1995) Phosphorylation switches specific for the cardiac isoform of myosin-binding protein-C. A modulator of cardiac contraction? EMBO J. 14, 1952–1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tardiff J. (2005) Sarcomeric proteins and familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Linking mutations in structural proteins to complex cardiovascular phenotypes. Heart Fail. Rev. 10, 237–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kelly M., Semsarian C. (2009) Multiple mutations in genetic cardiovascular disease. A marker of disease severity? Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2, 182–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Dijk S. J., Dooijes D., dos Remedios C., Michels M., Lamers J. M., Winegrad S., Schlossarek S., Carrier L., ten Cate F. J., Stienen G. J., van der Velden J. (2009) Cardiac myosin-binding protein C mutations and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy haploinsufficiency, deranged phosphorylation, and cardiomyocyte dysfunction. Circulation 119, 1473–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gruen M., Prinz H., Gautel M. (1999) cAPK phosphorylation controls the interaction of the regulatory domain of cardiac myosin-binding protein C with myosin-S2 in an on-off fashion. FEBS Lett. 453, 254–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gruen M., Gautel M. (1999) Mutations in β-myosin S2 that cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (FHC) abolish the interaction with the regulatory domain of myosin-binding protein-C. J. Mol. Biol. 286, 933–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kunst G., Kress K. R., Gruen M., Uttenweiler D., Gautel M., Fink R. H. (2000) Myosin-binding protein C, a phosphorylation-dependent force regulator in muscle that controls the attachment of myosin heads by its interaction with myosin S2. Circ. Res. 86, 51–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mohamed A. S., Dignam J. D., Schlender K. K. (1998) Cardiac myosin-binding protein C (MyBP-C). Identification of protein kinase A and protein kinase C phosphorylation sites. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 358, 313–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weisberg A., Winegrad S. (1996) Alteration of myosin cross-bridges by phosphorylation of myosin-binding protein C in cardiac muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 8999–9003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McClellan G., Kulikovskaya I., Winegrad S. (2001) Changes in cardiac contractility related to calcium-mediated changes in phosphorylation of myosin-binding protein C. Biophys. J. 81, 1083–1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cheng L. H., Qin Q. H., Ding G. L., Yao H., Floyd D., Woods D., Yang Q. L. (2003) Substitution of a constantly phosphorylated cardiac myosin-binding protein C in transgenic mouse heart enhances cardiac performance. Circulation 108, (Suppl IV) 90 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yuan C., Guo Y., Ravi R., Przyklenk K., Shilkofski N., Diez R., Cole R. N., Murphy A. M. (2006) Myosin-binding protein C is differentially phosphorylated upon myocardial stunning in canine and rat hearts. Evidence for novel phosphorylation sites. Proteomics 6, 4176–4186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sadayappan S., Gulick J., Osinska H., Barefield D., Cuello F., Avkiran M., Lasko V. M., Lorenz J. N., Maillet M., Martin J. L., Brown J. H., Bers D. M., Molkentin J. D., James J., Robbins J. (2011) A critical function for Ser-282 in cardiac myosin-binding protein-C phosphorylation and cardiac function. Circ. Res. 109, 141–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Blumenthal D. K., Charbonneau H., Edelman A. M., Hinds T. R., Rosenberg G. B., Storm D. R., Vincenzi F. F., Beavo J. A., Krebs E. G. (1988) Synthetic peptides based on the calmodulin-binding domain of myosin light chain kinase inhibit activation of other calmodulin-dependent enzymes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 156, 860–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tong C. W., Gaffin R. D., Zawieja D. C., Muthuchamy M. (2004) Roles of phosphorylation of myosin-binding protein-C and troponin I in mouse cardiac muscle twitch dynamics. J. Physiol. 558, 927–941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ding P., Huang J., Battiprolu P. K., Hill J. A., Kamm K. E., Stull J. T. (2010) Cardiac myosin light chain kinase is necessary for myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation and cardiac performance in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 40819–40829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sweeney H. L., Bowman B. F., Stull J. T. (1993) Myosin light-chain phosphorylation in vertebrate striated muscle. Regulation and function. Am. J. Physiol. 264, C1085-C1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhi G., Ryder J. W., Huang J., Ding P., Chen Y., Zhao Y., Kamm K. E., Stull J. T. (2005) Myosin light chain kinase and myosin phosphorylation effect frequency-dependent potentiation of skeletal muscle contraction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 17519–17524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Solaro R. J. (2008) Multiplex kinase signaling modifies cardiac function at the level of sarcomeric proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26829–26833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ratti J., Rostkova E., Gautel M., Pfuhl M. (2011) Structure and Interactions of myosin-binding protein C domain C0. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 12650–12658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lu Y., Kwan A. H., Trewhella J., Jeffries C. M. (2011) The C0C1 fragment of human cardiac myosin-binding protein C has common binding determinants for both actin and myosin. J. Mol. Biol. 413, 908–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jeffries C. M., Lu Y., Hynson R. M., Taylor J. E., Ballesteros M., Kwan A. H., Trewhella J. (2011) Human cardiac myosin-binding protein C. Structural flexibility within an extended modular architecture. J. Mol. Biol. 414, 735–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jeffries C. M., Whitten A. E., Harris S. P., Trewhella J. (2008) Small-angle x-ray scattering reveals the N-terminal domain organization of cardiac myosin-binding protein C. J. Mol. Biol. 377, 1186–1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chow J. Y., Jeffries C. M., Kwan A. H., Guss J. M., Trewhella J. (2010) Calmodulin disrupts the structure of the HIV-1 MA protein. J. Mol. Biol. 400, 702–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. André I., Kesvatera T., Jönsson B., Akerfeldt K. S., Linse S. (2004) The role of electrostatic interactions in calmodulin-peptide complex formation. Biophys. J. 87, 1929–1938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ababou A., Rostkova E., Mistry S., Le Masurier C., Gautel M., Pfuhl M. (2008) Myosin-binding protein C positioned to play a key role in regulation of muscle contraction. Structure and interactions of domain C1. J. Mol. Biol. 384, 615–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Franke D., Svergun D. I. (2009) DAMMIF, a program for rapid ab initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 42, 342–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ababou A., Gautel M., Pfuhl M. (2007) Dissecting the N-terminal myosin binding site of human cardiac myosin-binding protein C. Structure and myosin binding of domain C2. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9204–9215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Govada L., Carpenter L., da Fonseca P. C., Helliwell J. R., Rizkallah P., Flashman E., Chayen N. E., Redwood C., Squire J. M. (2008) Crystal structure of the C1 domain of cardiac myosin-binding protein-C. Implications for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Mol. Biol. 378, 387–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Weljie A. M., Vogel H. J. (2000) Tryptophan fluorescence of calmodulin binding domain peptides interacting with calmodulin containing unnatural methionine analogues. Protein Eng. 13, 59–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Muiño P. L., Callis P. R. (2009) Solvent effects on the fluorescence quenching of tryptophan by amides via electron transfer. Experimental and computational studies. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 2572–2577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Howarth J. W., Ramisetti S., Nolan K., Sadayappan S., Rosevear P. R. (2012) Structural insight into the unique cardiac myosin-binding protein-C motif. A partially folded domain. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 8254–8262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yap K. L., Kim J., Truong K., Sherman M., Yuan T., Ikura M. (2000) Calmodulin target database. J. Struct. Funct. Genomics 1, 8–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rhoads A. R., Friedberg F. (1997) Sequence motifs for calmodulin recognition. FASEB J. 11, 331–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chattopadhyaya R., Meador W. E., Means A. R., Quiocho F. A. (1992) Calmodulin structure refined at 1.7 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 228, 1177–1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Petoukhov M. V., Konarev P. V., Kikhney A. G., Svergun D. I. (2007) ATSAS 2.1. Toward automated and web-supported small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, S223–S228 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Svergun D. I. (1992) Determination of the regularization parameter in indirect-transform methods using perceptual criteria. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 25, 495–503 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Heidorn D. B., Trewhella J. (1988) Comparison of the crystal and solution structures of calmodulin and troponin C. Biochemistry 27, 909–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Matsushima N., Hayashi N., Jinbo Y., Izumi Y. (2000) Ca2+-bound calmodulin forms a compact globular structure on binding four trifluoperazine molecules in solution. Biochem. J. 347, 211–215 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jia W., Shaffer J. F., Harris S. P., Leary J. A. (2010) Identification of novel protein kinase A phosphorylation sites in the m-domain of human and murine cardiac myosin-binding protein-C using mass spectrometry analysis. J. Proteome Res. 9, 1843–1853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rybakova I. N., Greaser M. L., Moss R. L. (2011) Myosin-binding protein C interaction with actin. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 2008–2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Harris S. P., Lyons R. G., Bezold K. L. (2011) In the thick of it. HCM-causing mutations in myosin-binding proteins of the thick filament. Circ. Res. 108, 751–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Colbran R. J. (2004) Targeting of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem. J. 378, 1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Stull J. T., Kamm K. E., Vandenboom R. (2011) Myosin light chain kinase and the role of myosin light chain phosphorylation in skeletal muscle. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 510, 120–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]