Abstract

Anastomotic complications such as stenosis and leakage in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract can cause high patient morbidity and mortality. To identify the potential preconditions of these complications intraoperatively, we explored the use of two 700 nm near-infrared (NIR) fluorophores administered intraluminally: (1) chlorella, an over-the-counter herbal supplement containing high concentrations of chlorophyll and (2) methylene blue (MB). In parallel, we administered the 800 nm NIR fluorophore indocyanine green (ICG) intravenously to assess vascular function. Dual channel, real-time intraoperative imaging, and quantitation of the contrast-to-background ratio (CBR), were performed under normal conditions, or after anastomosis or leakage of the stomach and intestines in 35-kg Yorkshire pigs using the Fluorescence-Assisted Resection and Exploration (FLARE™) imaging system. Lumenal integrity could be assessed with relatively high sensitivity with either chlorella or MB, although chlorella provided significantly higher CBR. ICG angiography provided assessment of blood perfusion of normal, ischemic, and anastomotic areas of the GI tract. Used simultaneously, 700 nm (chlorella or MB) and 800 nm (ICG) NIR fluorescence permitted independent assessment of luminal integrity and vascular perfusion of the GI tract intraoperatively and in real time. This technology has the potential to identify critical complications, such as anastomotic leakage, intraoperatively, when correction is still possible.

Keywords: Dual-channel near-infrared fluorescence, chlorella, indocyanine green, GI tract, intraoperative assessment

INTRODUCTION

Thousands of gastrointestinal (GI) surgeries are performed annually, and while complications such as leakage from anastomoses are relatively uncommon, they can result in high patient morbidity and mortality. Many intraoperative tests have been developed to prevent complications at anastomotic sites, including endoscopic evaluation,[1] pneumatic testing,[2,3] and methylene blue (MB) testing to identify anastomotic leakage. However, an ideal method for assessing anastomoses would provide sensitive and simultaneous assessment of both luminal integrity and vascular perfusion intraoperatively, when it is still possible to correct any abnormalities found.

Intraoperative real-time near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence imaging has been used in many areas of surgery, including cardiovascular,[4] neurosurgery,[5] and biliary-tract surgery,[6] but oral administration of a fluorescent contrast agent for the purpose of GI surgery has not yet been reported. Gremlich and colleagues used cyanine dye as a fluorescent agent to study gastric emptying in mice,[7] but this technique has been neither applied to surgery of the GI tract, nor demonstrated in large animals or humans. For clinical use, the availability of NIR fluorophores is limited. The only NIR fluorophores approved by the FDA are MB and indocyanine green (ICG). Chen et al. demonstrated that chlorophyll shows NIR fluorescence around 700 nm wavelength;[8] therefore, we used chlorella, which contains chlorophyll, as a test compound with the potential for rapid clinical translation because it is already approved for use as an oral supplement.

The enabling technology for our study is the Fluorescence-Assisted Resection and Exploration (FLARE™) optical imaging system, which provides simultaneous acquisition of color video and 2 independent channels of invisible NIR fluorescence, one centered at 700 nm and the other at 800 nm. We hypothesized that when used with the FLARE™ imaging system, either of 2 clinically available 700 nm NIR fluorescent oral agents, chlorella containing chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b, or MB, could be used to assess luminal patency, while the clinically available 800 nm fluorescence agent indocyanine green (ICG) could be used to simultaneously assess vascular perfusion in the tissue under study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Stock solutions of chlorella (NOW® Foods, Bloomingdale, IL) having an effective chlorophyll concentration of 4 mM, chlorophyll a (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and chlorophyll b (Sigma-Aldrich) were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). A 32-mM solution of MB was purchased from Taylor Pharmaceuticals (Decatur, IL). ICG (Akorn, Inc., Decatur, IL) was prepared using the manufacturer’s diluent to create a 3.2-mM stock solution.

Animals

Animals were housed in an AAALAC-certified facility and were studied under the supervision of an approved institutional protocol. Seventeen female Yorkshire pigs (N = 17) were purchased from E.M. Parsons and Sons (Hadley, MA) with an average body weight of ≈ 35 kg. Animals were induced with 4.4-mg/kg intramuscular Telazol™ (Fort Dodge Labs, Fort Dodge, IA), intubated, and maintained with 2% isoflurane (Baxter Healthcare Corp., Deerfield, IL). Animals were fasted the morning of the experiment to prevent autofluorescence due to residual food. Following anesthesia, a 14-G central venous catheter was inserted into the external jugular vein, and saline was administered as needed. Electrocardiogram, heart rate, pulse oximetry, and body temperature were monitored throughout surgery. After surgery, anesthetized pigs were euthanized by rapid injection of 86-mg/kg Fatal-Plus solution (Vortech Pharmaceuticals, Dearborn, MI).

Measurement of Optical Properties

Optical properties of 10-μM solutions of chlorella, chlorophyll a, and chlorophyll b were first measured in 100% DMSO, and then in a “formulation” composed of 1% DMSO, 1% Cremophor EL (polyethoxylated castor oil; Sigma-Aldrich), and 98% distilled water. It should be noted that this formulation of chlorella is not FDA-approved for human use. Measurement of optical properties of MB was performed in water. Optical properties of ICG in serum have been previously described.[9] For measurements of fluorescence quantum yield (QY), oxazine 725 in ethylene glycol (QY = 19%)[10] was used as a calibration standard under conditions of matched absorbance at 655 nm. For in vitro optical property measurements, online fiberoptic HR2000 absorbance (200–1100 nm) and USB2000FL fluorescence (350–1000 nm) spectrometers (Ocean Optics, Dunedin, FL) were used. NIR excitation was provided by a 770-nm NIR laser diode light source (Electro Optical Components, Santa Rosa, CA) set to 8 mW and coupled through a 300-μm core diameter NA 0.22 fiber (Fiberguide Industries, Stirling, NJ). NIR fluorophore quenching was measured in a 0° geometry[11] using the FLARE™ imaging system.

NIR Fluorescence Imaging System

The dual-NIR channel FLARE™ imaging system has been described in detail previously.[12,13] In this study, 670 nm excitation and 760 nm excitation fluence rates used were 4.0 and 11.0 mW/cm2, respectively, with white light (400 to 650 nm) at 40,000 lx. Color video and 2 independent channels (700 nm and 800 nm) of NIR fluorescence images were acquired simultaneously with custom software at rates up to 15 Hz over a 15-cm diameter field of view (FOV). In the color-NIR merged images, 700 nm NIR fluorescence (chlorella or MB) and 800 nm fluorescence (ICG) were pseudo-colored red and green, respectively. The imaging system was positioned at a distance of 18 inches from the surgical field.

NIR Imaging of the GI Tract in Swine

For all experiments, a midline abdominal incision was performed and a nasogastric (NG) tube was inserted until palpable in the stomach. To assess luminal integrity, chlorella and MB were administered orally through the NG tube. Because the flow of chlorella or MB in the lumen mirrored peristalsis and was generally fast, we clamped the anal side of the leakage point and the anastomotic site using our fingers or clamp forceps for better observation. Four animals (n = 4) received 100 mL of 40 μM chlorella in formulation. An additional 4 animals (n = 4) received 100 mL of 32 μM MB. As indicated, a leakage point with a diameter of 3 mm was created on the jejunum using an electric scalpel. Quantitative assessment was performed using the contrast to background ratio (CBR) as defined in Statistical Analysis (below).

To assess sensitivity to leakage of an anastomosis, a gastrojejunostomy (side-to-side anastomosis of the stomach and the jejunum) was performed in one animal (n=1). The anastomosis was created by hand, using the Albert-Lembert technique with 4-0 silk suture, the first layer being an Albert suture, and the second being a Lembert suture. Leakage was created using the same procedure as described above.

To assess the stricture of the anastomoses, 4 jejunojejunostomies (end-to-end anastomoses) were created in each pig (n = 4; 16 total anastomoses). All anastomoses were created by hand, using the Albert-Lembert technique with 4-0 silk suture; a varying bite was used to adjust the luminal diameter and wall thickness of the site. After creating anastomoses, 100 mL of 40 μM chlorella in formulation was orally administered. To measure the correlation between wall thickness and CBR, each anastomosis site was resected and wall thickness measured with a caliper.

As we have reported previously, the intravenously injected, 800 nm fluorophore ICG can be used for both qualitative[14] and quantitative[15] assessment of tissue perfusion in the context of surgical anatomy. ICG was administered intravenously after oral administration of chlorella to simultaneously assess tissue perfusion, luminal integrity, and surgical anatomy of GI anastomoses. For proof of principle, a jejunojejunostomy and an ischemic model were prepared in each pig (n = 4 pigs). The jejunojejunostomy was created by hand (as described above). For the ischemic model, 3 to 4 arteries and veins were ligated with 3-0 silk suture. Via the nasogastric tube, 100 mL of 40 μM chlorella was administered. Then, 10 mL of 80 μM ICG in saline were infused as a rapid bolus via the external jugular vein. Images were recorded at the time of injection (T = 0 min), then every 10 s until 120 s post-injection using a camera exposure time of 150 ms.

Quantitation and Statistical Analysis

The background (BG) intensity and fluorescence intensity (FI) of a 1 cm diameter circular region of interest (ROI) over the GI tract were quantified using custom software. The performance metric for this study was the contrast-to-background ratio (CBR); where exposed rectus muscles were used as background. CBR = (FI of ROI − BG intensity)/BG intensity. Results were presented as mean ± SEM. A one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test were used to assess the statistical differences between multiple groups. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Optical Properties of Chlorella in Formulation and MB in Water

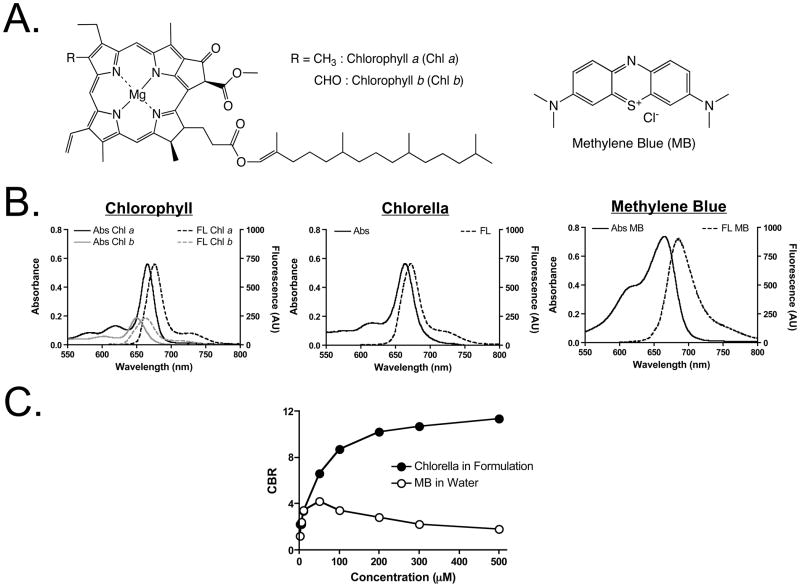

The chemical structures of the 700 nm fluorophores used in this study are shown in Figure 1A. Prior to in vivo experiments, the optical properties of chlorella, chlorophyll a and b, and MB were fully characterized. Chlorella has a maximum solubility of 3.8 mg/mL in DMSO, but only 0.01 mg/mL in water. Chlorella also has very low solubility in other organic solvents such as methanol, ethanol, acetone, dichloromethane, and chloroform (data not shown). Because DMSO is the optimal solvent for dissolving chlorella, a 4-mM (concentration of chlorophyll) stock solution was prepared in 100% DMSO. The optimal formulation was prepared by dissolving this stock solution 100-fold in water (1% final DMSO) and supplementing with 1% Cremophor EL.

Figure 1. Chemical Structures and Optical Properties of Chlorella, Chlorophyll a and b, and Methylene Blue (MB).

A. Chemical structures of chlorophyll (Chl) a and b (left) and MB (right).

B. Absorbance (Abs) and fluorescence (FL) spectra of the chlorophylls in formulation (10 μM; left), chlorella in formulation (10 μM; middle), and MB in water (10 μM; right).

C. Fluorescence quenching curves for chlorella in formulation and MB in water.

Peak absorption of chlorella, chlorophyll a, and chlorophyll b, each in formulation, and MB in water was at 667 nm, 668 nm, 645 nm, and 665 nm, respectively; peak emission was at 671 nm, 677 nm, 662 nm, and 687 nm, respectively (Figures 1B and Table 1). The extinction coefficient (56,500 M−1cm−1) and QY (14.2%) of chlorella in formulation were close to those in DMSO, which were the same or higher than the values of chlorophyll a and b (Table 1). In formulation, chlorella exhibited significantly less concentration-dependent quenching than MB (Figure 1C). At all concentrations tested, chlorella exhibited an absolute fluorescence intensity 3-fold higher than MB and was therefore preferred for in vivo experiments.

Table 1.

Optical Properties of Chlorophyll a, Chlorophyll b, Chlorella, and Methylene Blue (MB)

| Optical Property | Chlorophyll a | Chlorophyll b | Chlorella | MB in Water | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| DMSO | Formulation* | DMSO | Formulation* | DMSO | Formulation* | ||

| Extinction Coefficient (M−1cm−1) | 74,200 | 56,500 | 22,500 | 18,900 | 74,200 | 56,500 | 74,400 |

| Absorbance Maximum (nm) | 667 | 668 | 647 | 645 | 666 | 667 | 665 |

| Emission Maximum (nm) | 674 | 677 | 663 | 662 | 671 | 671 | 687 |

| Quantum Yield (%) | 24.4 | 10.2 | 10.4 | 9.0 | 19.2 | 14.2 | 4.5 |

DMSO: dimethylsulfoxide;

Formulation is composed of 1% DMSO, 1% Cremophor EL, and 98% distilled water.

Assessment of Luminal Integrity of the GI Tract using NIR Fluorescence

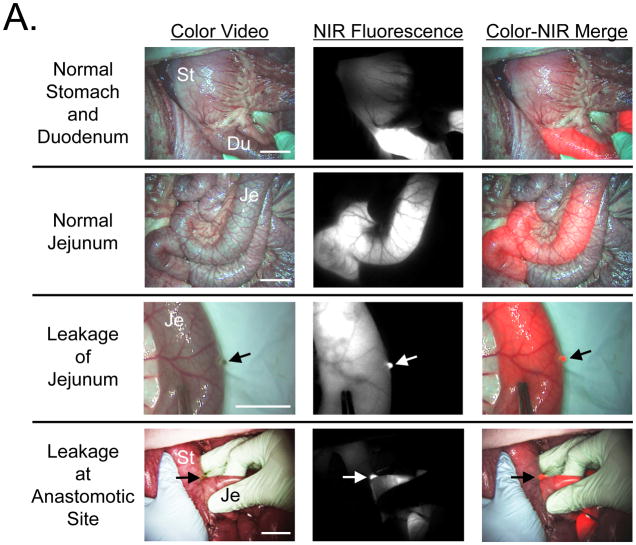

After infusion of either MB (not shown) or chlorella (Figure 2A) into the GI tract, the lumen became brightly fluorescent at 700 nm. Importantly, imaging was performed in real time, therefore, the surgeon had dynamic information about luminal flow that is not obvious from these still images.

Figure 2. Assessment of Luminal Integrity of the GI Tract.

A. Assessment of luminal integrity under conditions of normal stomach and duodenum (top row), normal jejunum (2nd row), leakage of jejunum (3rd row), and leakage at the anastomotic site of a gastrojejunostomy (bottom row) after infusion of 100 mL of 40 μM chlorella in formulation into the GI tract. Shown are color video (left), 700 nm NIR fluorescence (NIR fluorescence channel #1; middle), and a merge of the two (right). NIR fluorescence is pseudo-colored in red in the color-NIR merged image. St: Stomach, Du: Duodenum, and Je: Jejunum. Arrow indicates leakage point. Scale bar = 3 cm.

B. Quantitative comparison of CBR (mean ± SEM) measured in vivo among control (before administration), MB, and chlorella in stomach, duodenum, jejunum, and after leakage from the jejunum. St: Stomach, Du: Duodenum, and Je: Jejunum. P values for the indicated statistical comparisons are as follows: * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01; *** =P < 0.001.

The thickness of the tissue being imaged had a significant impact on the overall fluorescence intensity. For example, the thick wall of the stomach attenuated much more light than the thinner wall of the duodenum or jejunum (Figure 2A). Quantitative comparison of MB and chlorella at different sites along the GI tract confirmed that chlorella provided 1.5- to 3-fold higher signal intensity than MB (Figure 2B).

More significant was the sensitivity of this technology to leakage either in the wall of the bowel or at the site of an anastomosis (Figures 2A). In this case, chlorella provided approximately 2-fold higher sensitivity than MB (Figure 2B). Of note, neither fluorophore nor the NIR fluorescent light itself changed the look or color of the surgical field; the fluorophores were both used as dilute solutions, and NIR fluorescent light is invisible to the human eye.

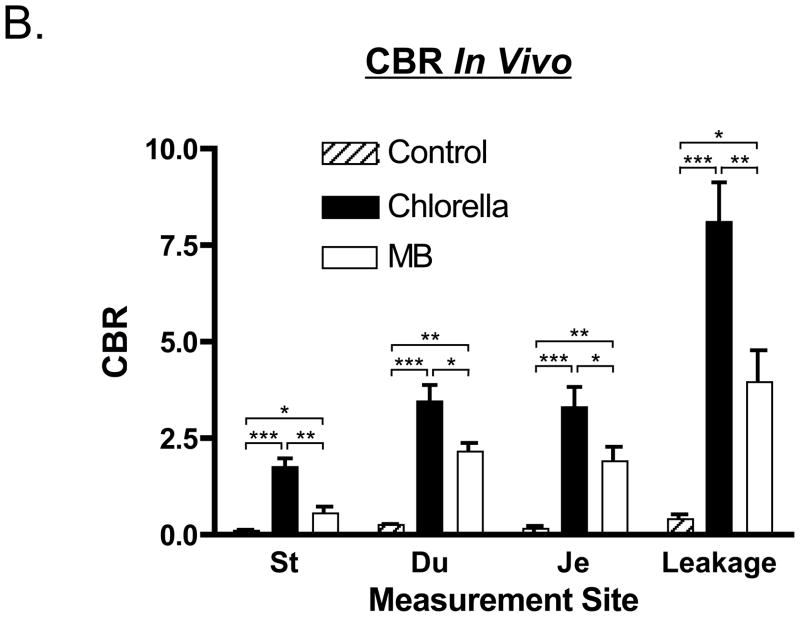

Assessment of the Anastomotic Site

In a total of 16 jejunojejunostomy models, different bites of Lembert sutures were used to alter the diameter of the anastomosis (Figure 3A). As seen both qualitatively (Figure 3A) and quantitatively (Figure 3B), the fluorescence intensity of the anastomotic site was inversely correlated with the thickness of the wall. In the example shown in Figure 3A, the thickness of J-J#1 was 2.5 mm, which corresponded to a CBR of 4.6, whereas the thickness of J-J#2 was 6.0 mm and showed a CBR of only 0.84. Because of the strong effect of tissue thickness on fluorescence intensity, it was not possible to develop a quantitative fluorescence metric that permitted accurate assessment of the lumen diameter of the anastomosis.

Figure 3. Assessment of Patency at the Anastomotic Site using Chlorella.

A. Assessment of luminal patency in representative jejunojejunostomies using Albert-Lembert sutures. Shown is a normal jejunojejunostomy (J-J #1; top) and a jejunojejunostomy with an inadequate suture (J-J #2; bottom). For assessment, 100 mL of 40 μM chlorella in formulation was infused into the GI tract. Shown are color video (left), 700 nm NIR fluorescence (fluorescence channel #1; middle), and a merge of the two (right). NIR fluorescence is pseudo-colored in red in the Color-NIR merged image. Arrow indicates site of anastomosis. Scale bar = 3 cm.

B. Quantitative correlation between CBR at the anastomotic site and wall thickness (n = 4 pigs; 16 anastomoses total). The correlation coefficient shown is from fitting with a one-phase exponential decay.

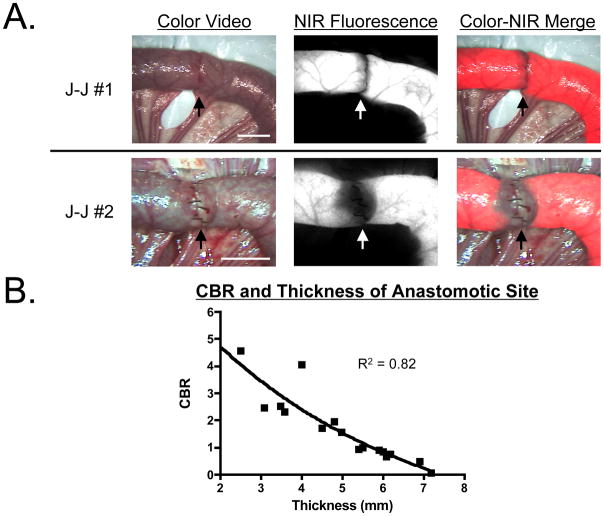

Simultaneous Assessment of Lumen Integrity and Vascular Perfusion using Dual-NIR Fluorescence Imaging

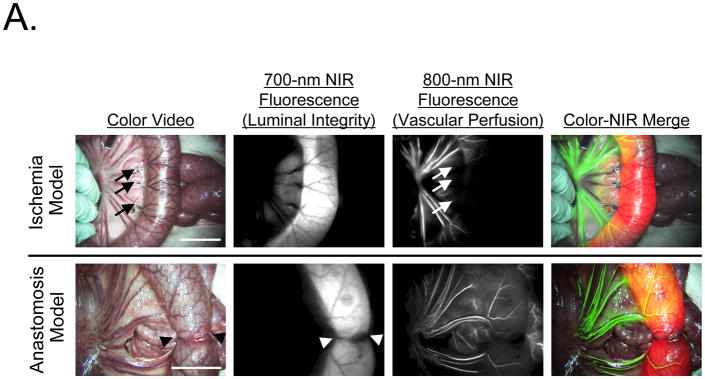

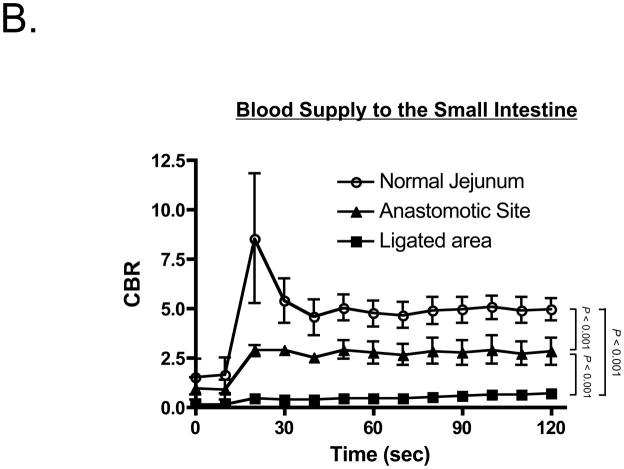

Vascular perfusion could be independently assessed by intravenous injection of 10 mL of 80 μM ICG after infusion of 100 mL of 40 μM chlorella dissolved in formulation into the small intestine to assess luminal integrity (Figure 4A). Importantly, ICG injection could be repeated as many times as needed, provided that a ≈ 15 min period between doses of was employed to minimize dose stacking. In both ischemia and anastomosis models, the lumen and vessels of the GI tract could be assessed simultaneously and in real time (Figure 4A). Quantitative assessment of ICG vascular perfusion over time revealed statistically significant differences in fluorescence intensity of the normal bowel wall, the infarcted bowel wall, and the anastomotic site (Figure 4B). The predictive capability of quantitative ICG perfusion measurements will be reported elsewhere (Matsui et al., manuscript in review).

Figure 4. Simultaneous Assessment of Luminal Integrity and Vascular Perfusion of the GI Tract using Dual-Channel NIR Fluorescence.

A. Ischemic models (top row) were created by the ligation of veins and arteries, and anastomosis models (bottom row) were created using an Albert-Lembert suture. For assessment of luminal integrity, 100 mL of 40 μM chlorella (a 700 nm fluorophore) in formulation was infused into the jejunum. For assessment of vascular perfusion, a 10 mL bolus of 80 μM ICG (an 800 nm fluorophore) in saline was injected intravenously. Areas of vascular compromise (arrows) and the anastomotic site (arrowheads) are indicated. Shown are color video (left), 700 nm NIR fluorescence (NIR fluorescence channel #1; 2nd column), 800 nm NIR fluorescence (NIR fluorescence channel #2; 3rd column) and a pseudo-colored merge of the three (right). In the merged image, NIR fluorescence channel #1 (chlorella) and NIR fluorescence channel #2 (ICG) are pseudo-colored in red and green, respectively. Scale bar = 3 cm.

B. Quantitative comparison of CBR (mean ± SEM) among normal jejunum, the anastomotic site, and ligated vessels in n = 4 pigs. Shown are the P values for the indicated statistical comparisons.

DISCUSSION

Post-operative anastomotic leaks remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality following GI surgery.[16] The risk of this complication would likely be minimized if reparable problems could be identified intraoperatively. Unfortunately, clinical judgment alone has been shown to have low sensitivity and specificity for predicting anastomotic leakage.[17] As reviewed above, many types of real-time techniques are available for assessing anastomotic sites, but the use of NIR fluorescence imaging has not yet been reported. Although we studied only gastrojejunostomy and jejunojejunostomy models, our approach will likely be useful for other GI anastomoses, such as during esophagectomy. It is widely recognized that esophageal anastomoses are subject to high rates of leakage (4.4%-10.9%) and subsequently high rates of mortality (12%-50%).[16,18,19]

Invisible NIR fluorescent light offers several advantages over visible light for surgical imaging, including high sensitivity and specificity, and low tissue autofluorescence (reviewed in [11,20]). Importantly, several NIR fluorescence-imaging systems, both investigational and FDA-approved, are now available for clinical use (reviewed in [11]). The FLARE™ system, for example, has already been translated to the clinic for investigational use in breast cancer sentinel lymph node mapping[13] and perforator artery mapping;[21] additionally, prototype versions of the minimally invasive FLARE™ (m-FLARE™) for laparoscopy have also recently been described.[22]

The only impediment to widespread clinical use of this technology is the availability of suitable contrast agents. We focused our study on chlorella and MB, two 700 nm fluorescent agents that are either already clinically available or pose low potential risk. Chlorella is a chlorophyll-containing, over-the-counter, general nutritional supplement of green algae sold in the United States and worldwide. Because intact green algae are poorly fluorescent, chlorella powder must be dissolved in DMSO and then diluted in water containing the pharmaceutical solubilizer Cremophor EL. Both DMSO and Cremophor EL are widely used in pharmaceutical formulations,[23,24] and have been used for oral delivery[25] at extremely high concentrations (for example, 1 to 6 g[25] as opposed to the 1 g used in our study). Although chlorella in this formulation caused high fluorescence intensity both in vivo and in vitro, it must be stressed that this particular formulation of chlorella is not FDA-approved for human use. An immediate alternative to chlorella is MB, which is already used for assessing GI patency. However, when employed as a NIR fluorophore, it generates lower fluorescence intensity than chlorella and needs to be appropriately diluted so that quenching (Figure 1C) does not occur.

Using chlorella or MB, we demonstrated that luminal patency and leakage could be identified in real time with high sensitivity. However, thick tissue effectively attenuates NIR fluorescent light, making quantitation of luminal diameter very difficult. Simple reflectance-based NIR fluorescent techniques are most effective in scattering tissues less than approximately 5 mm in thickness or depth (see, for example, Figure 3B). At the very least, the ability to dynamically image luminal flow, and to see into the lumen noninvasively, should provide qualitative information that is not presently available. Also, the relative CBR difference between lumen and anastomosis permits an estimate of anastomotic thickness (Figure 3B).

A complete assessment of the bowel after an anastomosis includes measurement of tissue perfusion in addition to lumenal integrity. Using the dual NIR channel capabilities of FLARE™, we demonstrated that the 800 nm NIR fluorophore ICG permits repetitive assessment of blood flow to the bowel, although it should be remembered that ICG is cleared by the liver and begins appearing in small bowel within ≈ 15 min after intravenous injection, with peak excretion at 30 to 90 min [26].

Using ICG angiography, there appears to be a quantitative difference between blood flow to the anastomotic site, the nearby normal bowel, and between the anastomotic site and the ligated site (Figure 4B). Although blood perfusion will often change during surgery, the ability to quantify perfusion may prove useful. Indeed, a recently completed study by our laboratory (Matsui et al., manuscript in review) suggests that such quantitative differences in ICG perfusion can predict bowel survival. Moreover, a large clinical study by Kudszus et al. [27] suggests that evaluation of tissue perfusion using ICG can halve the rate of post-operative complications from all anastomoses, and reduce the rate of leakage from hand-sewn anastomoses by 84%. Thus, the dual channel NIR fluorescence imaging technology we describe in this study has the potential to permit surgical correction intraoperatively.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Financial Support: This study was funded by National Institutes of Health (National Cancer Institute) grants #R01-EB-005805 and #R01-CA-115296 to JVF.

We thank Rita G. Laurence for assistance with animal surgery, Lindsey Gendall, Mary M. McCarthy, and Lorissa A. Moffitt for editing, and Eugenia Trabucchi for administrative assistance. This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grants #R01-EB-005805 and #R01-CA-115296 to JVF. All FLARE™ technology is owned by Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, a teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. As inventor, Dr. Frangioni may someday receive royalties if products are commercialized. Dr. Frangioni is the founder and unpaid director of The FLARE Foundation, a non-profit organization focused on promoting the dissemination of medical imaging technology for research and clinical use.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BG

Background

- CBR

Contrast-to-background ratio

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- FI

Fluorescent intensity

- FLARE™

Fluorescence-Assisted Resection and Exploration imaging system

- FOV

Field of view

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- ICG

Indocyanine green

- MB

Methylene blue

- NG

Nasogastric

- NIR

Near-infrared

- QY

Quantum yield

- ROI

Region of interest

References

- 1.Sekhar N, Torquati A, Lutfi R, Richards WO. Endoscopic evaluation of the gastrojejunostomy in laparoscopic gastric bypass. A series of 340 patients without postoperative leak. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:199–201. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amarasinghe DC. Air test as an alternative to methylene blue test for leaks. Obes Surg. 2002;12:295–6. doi: 10.1381/096089202762552557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kligman MD. Intraoperative endoscopic pneumatic testing for gastrojejunal anastomotic integrity during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1403–5. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakayama A, del Monte F, Hajjar RJ, Frangioni JV. Functional near-infrared fluorescence imaging for cardiac surgery and targeted gene therapy. Mol Imaging. 2002;1:365–77. doi: 10.1162/15353500200221333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferroli P, Tringali G, Albanese E, Broggi G. Developmental venous anomaly of petrous veins: intraoperative findings and indocyanine green video angiographic study. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:ONS418-21. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000326029.47090.16. discussion ONS421-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka E, Choi HS, Humblet V, Ohnishi S, Laurence RG, Frangioni JV. Real-time intraoperative assessment of the extrahepatic bile ducts in rats and pigs using invisible near-infrared fluorescent light. Surgery. 2008;144:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gremlich HU, Martinez V, Kneuer R, Kinzy W, Weber E, Pfannkuche HJ, Rudin M. Noninvasive assessment of gastric emptying by near-infrared fluorescence reflectance imaging in mice: pharmacological validation with tegaserod, cisapride, and clonidine. Mol Imaging. 2004;3:303–11. doi: 10.1162/15353500200404127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen M, Schliep M, Willows RD, Cai ZL, Neilan BA, Scheer H. A red-shifted chlorophyll. Science. 2010;329:1318–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1191127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohnishi S, Lomnes SJ, Laurence RG, Gogbashian A, Mariani G, Frangioni JV. Organic alternatives to quantum dots for intraoperative near-infrared fluorescent sentinel lymph node mapping. Mol Imaging. 2005;4:172–81. doi: 10.1162/15353500200505127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sens R, Drexhage KH. Fluorescence quantum yield of oxazine and carbazine laser dyes. J Luminesc. 1981;24:709–712. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee BT, Hutteman M, Gioux S, Stockdale A, Lin SJ, Ngo LH, Frangioni JV. The FLARE intraoperative near-infrared fluorescence imaging system: a first-in-human clinical trial in perforator flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1472–81. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f059c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gioux S, Kianzad V, Ciocan R, Gupta S, Oketokoun R, Frangioni JV. High-power, computer-controlled, light-emitting diode-based light sources for fluorescence imaging and image-guided surgery. Mol Imaging. 2009;8:156–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Troyan SL, Kianzad V, Gibbs-Strauss SL, Gioux S, Matsui A, Oketokoun R, Ngo L, Khamene A, Azar F, Frangioni JV. The FLARE intraoperative near-infrared fluorescence imaging system: a first-in-human clinical trial in breast cancer sentinel lymph node mapping. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2943–52. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0594-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsui A, Lee BT, Winer JH, Vooght CS, Laurence RG, Frangioni JV. Real-time intraoperative near-infrared fluorescence angiography for perforator identification and flap design. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:125e–7e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31819a3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsui A, Lee BT, Winer JH, Laurence RG, Frangioni JV. Submental perforator flap design with a near-infrared fluorescence imaging system: the relationship among number of perforators, flap perfusion, and venous drainage. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:1098–104. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b5a44c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pickleman J, Watson W, Cunningham J, Fisher SG, Gamelli R. The failed gastrointestinal anastomosis: an inevitable catastrophe? J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:473–82. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karliczek A, Harlaar NJ, Zeebregts CJ, Wiggers T, Baas PC, van Dam GM. Surgeons lack predictive accuracy for anastomotic leakage in gastrointestinal surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:569–76. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0658-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alanezi K, Urschel JD. Mortality secondary to esophageal anastomotic leak. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;10:71–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Briel JW, Tamhankar AP, Hagen JA, DeMeester SR, Johansson J, Choustoulakis E, Peters JH, Bremner CG, DeMeester TR. Prevalence and risk factors for ischemia, leak, and stricture of esophageal anastomosis: gastric pull-up versus colon interposition. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:536–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.11.026. discussion 541–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frangioni JV. In vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:626–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee BT, Matsui A, Hutteman M, Lin SJ, Winer JH, Laurence RG, Frangioni JV. Intraoperative near-infrared fluorescence imaging in perforator flap reconstruction: current research and early clinical experience. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2010;26:59–65. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1244805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashitate Y, Tanaka E, Stockdale A, Choi HS, Frangioni JV. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging of thoracic duct anatomy and function in open surgery and video-assisted thoracic surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142:31–38. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schrijvers DL. Extravasation: a dreaded complication of chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2003;14(Suppl 3):iii26–30. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dimitrakov J, Kroenke K, Steers WD, Berde C, Zurakowski D, Freeman MR, Jackson JL. Pharmacologic management of painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1922–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.18.1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amemori S, Iwakiri R, Endo H, Ootani A, Ogata S, Noda T, Tsunada S, Sakata H, Matsunaga H, Mizuguchi M, Ikeda Y, Fujimoto K. Oral dimethyl sulfoxide for systemic amyloid A amyloidosis complication in chronic inflammatory disease: a retrospective patient chart review. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:444–9. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1792-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutteman M, van der Vorst JR, Mieog JS, Bonsing BA, Hartgrink HH, Kuppen PJ, Lowik CW, Frangioni JV, van de Velde CJ, Vahrmeijer AL. Near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging in Patients Undergoing Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Eur Surg Res. 2011;47:90–97. doi: 10.1159/000329411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kudszus S, Roesel C, Schachtrupp A, Hoer JJ. Intraoperative laser fluorescence angiography in colorectal surgery: a noninvasive analysis to reduce the rate of anastomotic leakage. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2010;395:1025–30. doi: 10.1007/s00423-010-0699-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]