Abstract

The Memory and Aging Project is a longitudinal, epidemiologic clinical-pathologic cohort study of common chronic conditions of aging with an emphasis on decline in cognitive and motor function and risk of Alzheimer's disease (AD). In this manuscript, we first summarize the study design and methods. Then, we present data on: 1) the relation of motor function to cognition, disability, and death; 2) the relation of risk factors to cognitive and motor outcomes, disability and death; 3) the relation of neuropathologic indices to cognitive outcomes; 4) the relation of risk factors to neuropathologic indices; and 5) additional study findings. The findings are discussed and contextualized.

Keywords: Dementia, Alzheimer's disease, cognitive function, epidemiology, clinical-pathologic study

INTRODUCTION

The number of persons with AD is expected to increase markedly in the coming decades [1,2]. With a public health problem of this magnitude, disease prevention provides the best long-term strategy for reducing the burden of cognitive impairment in the U.S. [3,4]. Disease prevention requires the identification of risk factors for cognitive decline and the development of strategies to delay the onset of cognitive impairment through behavior modification or pharmacologic interventions. However, this goal has proved elusive [5,6] due to the complexity of the disease. Although a general consensus regarding the clinical and pathologic diagnoses of AD had emerged by the mid 1980's [7,8], it was subsequently found that AD pathology can be widespread in persons without dementia [9–13]. Some investigators suggested that these persons had greater brain reserve [9].

The concept of reserve applies to many human physiologic systems (e.g., pulmonary, renal, hepatic, cardiac [14–20]). These functional systems are highly redundant and considerable tissue destruction must take place before systems are compromised and signs of disease become evident. Although the nervous system is more complex, it has long been recognized that some type of reserve can protect the nervous system from expressing pathology or injury as functional impairment. For example, a number of studies in the early 1990s found that education and occupation were associated with a reduction in AD risk [21,22], and investigators concluded that these lifestyle factors might alter brain reserve. Data on the relation of head circumference to AD provided further support for the reserve concept [23,24]. Finally, neuroimaging studies provided evidence of neurobiologic correlates of reserve [25–28].

The Memory and Aging Project began in 1997 [29]. The overall goal of the study is to identify factors associated with the maintenance of cognitive health despite the accumulation of AD and other pathology. When the Memory and Aging Project began, there were a number of ongoing epidemiologic studies that included, but did not require, organ donation. However, there were only two cohort studies of aging and AD that required organ donation: the Nun Study and the Religious Orders Study. Both studies were restricted to Catholic clergy and included participants with a restricted range of life experiences and socioeconomic status and exceedingly high educational attainment. The Memory and Aging Project was specifically designed to complement and extend other ongoing epidemiologic studies that included organ donation. The study design is similar to the Religious Orders Study in that it enrolls persons without dementia who agree to annual clinical evaluation and organ donation. However, it enrolls participants with a much wider range of life experiences and socioeconomic status with a goal of enrolling a third of participants with 12 or fewer years of education. Further, the study requires that participants agree to donate spinal cord, muscle and nerve, in addition to brain, to support studies of decline in motor function and disability as well as cognitive function. More recently, participants have been encouraged to participate in a variety of additional studies including studies of physical activity and sleep using actigraphy, structural and resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies, and studies of well-being, behavioral economics, and health and financial decision making.

METHODS

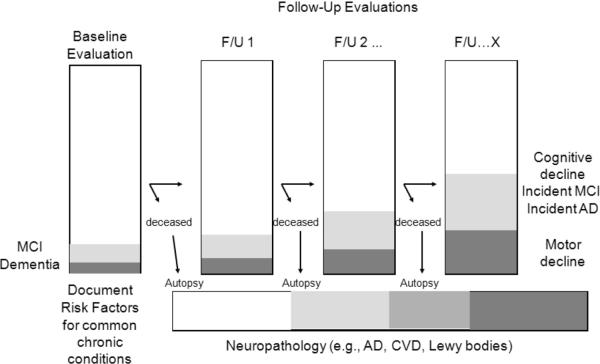

Study Design

The Memory and Aging Project is funded by the National Institute on Aging and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rush University Medical Center. Older persons without known dementia must agree to an assessment of risk factors, blood donation, and a detailed clinical evaluation each year. Further, all participants also agree to donation of brain, the entire spinal cord, and selected nerve and muscles at the time of death.

Study participants are primarily recruited from retirement communities throughout northeastern Illinois Fig. (1). The study primarily enrolls residents of continuous care retirement communities. Several features of these facilities and the study design enhance the validity and generalizability of the study. Because the only exclusion is the inability to sign the Anatomical Gift Act, and because all clinical evaluations are performed as home visits, co-morbidities common in population-based epidemiologic studies are well represented; this reduces the “healthy volunteer effect” seen in many cohort studies [30]. The home visits reduce participant burden facilitating high rates of follow-up. Follow-up rates are further enhanced because these facilities provide all levels of care from independent living to unskilled and skilled nursing on campus. This also enhances autopsy rates as many participants die on campus and the Anatomical Gift Act allows us to work directly with facility staff and the funeral home to arrange the autopsy. Residents of continuous care retirement communities are predominantly white and tend to be more affluent. Therefore, the study also recruits from Section 8 and Section 202 housing subsidized by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, retirement homes, and through local churches and other social service agencies serving minorities and low-income elderly.

Fig. (1).

Major locations of Memory and Aging Project participants in Northeastern Illinois.*

*Alden of Waterford, Aurora; Beacon Hill, Lombard; Bethlehem Woods, La Grange Park; Clare Oaks Retirement Community, Bartlett; Covenant Village, Northbrook; Elgin Housing Authority, Elgin; Fairview Village, Downer's Grove; Frances Manor, Des Plaines; Franciscan Village, Lemont; Friendship Village, Schaumburg; Garden House, Calumet City; Green Castle, Arlington Heights; Holland Home, South Holland; King-Bruwaert House, Burr Ridge; Kingston Manor, Chicago; Lawrence Manor, Matteson; Luther Village, Arlington Heights; Marian Village, Homer Glen; Mayslake Village, Oak Brook; Peace Village, Palos Park; Renaissance, Hillside; Victorian Village, Tinley Park; St. Andrew's Manor, Phoenix; St. Paul Home, Chicago; The Breakers of Edgewater, Chicago; The Birches, Clarendon Hills; The Holmstad, Batavia; The Imperial, Chicago; The Mills, Oak Park; The Moorings, Arlington Heights; The Oaks, Oak Park; Trinity United Church Of Christ, Chicago; Victory Lakes, Lindenhurst; Village Woods, Crete; Washington Jane Smith, Chicago; Windsor Park Manor, Carol Stream; Wyndemere, Wheaton.

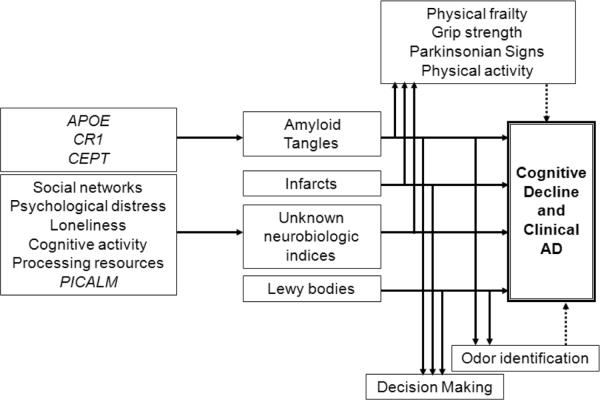

The study design allows the following types of analyses to be conducted within a single dataset Fig. (2): 1) the relation of risk factors with incident AD, incident MCI, and decline in cognitive and motor function; 2) the relation of neurobiologic indices with AD, MCI, and cognitive and motor function; and 3) modeling neurobiologic pathways linking risk factors to clinical phenotypes.

Fig. (2).

Overall study design of the Rush Memory and Aging Project*

*Through November, 2011, the baseline evaluation was completed on 1,489 persons. There have been 343 cases of incident MCI and 250 cases of incident dementia, and 424 autopsies.

Demographic Variables and Socioeconomic Status

Race and ethnicity are ascertained using the 1990 U. S. Census questions. Measures of socioeconomic status include education and occupation. Birth addresses were linked to 1920 census data to determine early-life socioeconomic status [31]. Age 40 addresses were linked to 1960 census data to determine mid-life socioeconomic status. Other indicators of early life socioeconomic status include parental education and occupation.

Clinical Diagnoses of Dementia, AD, MCI and Other Medical Conditions

Clinical evaluation, self-report, and medication inspection are used to document medical conditions. The diagnostic process is identical to that performed in the Religious Orders Study. Briefly, a decision tree designed to mimic expert clinical judgment was implemented by computer to inform several clinical diagnoses, including dementia and AD [32]. It combines data reduction techniques for the cognitive performance testing with a series of discrete clinical judgments made in series by a neuropsychologist and a clinician. Presumptive diagnoses of dementia and AD are calculated that conform to accepted clinical criteria [7]. The clinician is asked to agree or disagree with the decisions. An algorithm uses these decisions to provide diagnoses of MCI and amnestic MCI [33]. Persons with MCI are judged to have cognitive impairment by neuropsychologic testing without a diagnosis of dementia by the clinician. Persons without dementia or MCI are categorized as no cognitive impairment (NCI). A similar decision tree also is employed to aid the diagnosis of stroke, cognitive impairment due to stroke (vascular dementia), parkinsonism, Parkinson's disease (PD), and depression following accepted criteria [34–36]. The evaluation is designed to reduce costs and enhance uniformity of diagnostic decisions over time and space [37,38]. Other less common diagnoses are made by contemporary standards [39].

Most of the remaining diagnoses are by self report, including cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) and cardiovascular diseases (e.g., myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, claudication) [40] and musculoskeletal pain [41]. Tobacco and alcohol use is documented [42]. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure ae measured directly, and all over the counter and prescription medications are recorded. Thus, a diagnosis of diabetes is based on self report and medication use (e.g., insulin) [42]. Sensitivity analyses are routinely performed to ensure findings are not driven by inconsistent information (e.g., diabetes limited to persons on medications). We are also collecting hemoglobin A1C on a subset of participants.

Cognitive Performance Tests

A battery of 21 cognitive performance tests is administered each year (Table 1) [43–55]. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [43] is primarily used to describe the cohort. Eleven tests are used for diagnostic classification. Nineteen tests that assess a range of cognitive abilities are used to construct separate summary measures of global cognitive function and five cognitive domains, including episodic memory, semantic memory, working memory, perceptual speed, and visuospatial ability. The composite measures are created by converting each test within each domain to a z-score and averaging the z-scores, as previously described [56]. Seven tests can be administered by telephone. The telephone version yields composites for episodic memory, semantic memory, and working memory, in addition to global cognition.

Table 1.

Cognitive Performance Tests in the Memory and Aging Project

| Test | Diagnoses | Composite | Telephone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mini-Mental State Examination | Orientation | MMSE22 | |

| Logical Memory Ia | Episodic memory | ||

| Logical Memory IIa | Episodic memory | ||

| Immediate story recall | Episodic memory | Episodic memory | |

| Delayed story recall | Memory | Episodic memory | Episodic memory |

| Word List Memory (3 trials) | Episodic memory | ||

| Word List Recall | Memory | Episodic memory | |

| Word List Recognition | Memory | Episodic memory | |

| Complex Ideational Material | Language | ||

| Boston Naming Test | Language | Semantic memory | |

| Category Fluency (fruits, animals) | Language | Semantic memory | Semantic memory |

| National Adult Reading test | Semantic memory | ||

| Digit Span Forward | Working memory | Working memory | |

| Digit Span Backward | Attention | Working memory | Working memory |

| Digit Ordering | Working memory | Working memory | |

| Symbol Digit Modalities Test | Attention | Perceptual speed | |

| Number Comparison | Perceptual speed | ||

| Stroop word reading | Perceptual speed | ||

| Stroop color naming | Perceptual speed | ||

| Judgment of Line Orientation | Visuospatial | Visuospatial ability | |

| Standard Progressive Matrices | Visuospatial | Visuospatial ability |

Motor Function and Structure and Physical Frailty

The clinical evaluation includes a modified version of the motor portion of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (modified UPDRS) which is used to assess four parkinsonian domains including bradykinesia, rigidity, parkinsonian gait, and tremor, in addition to a composite global measure of parkinsonism [40].

Upper and lower extremity motor strength and performance tests were collected as previously described [57]. These include grip and pinch strength measured by hydraulic dynamometers, arm abduction, arm flexion, arm extension, hip flexion, knee extension, plantar flexion, and ankle dorsiflexion measured with handheld dynamometry; time and number of steps to walk 2.4 meters and to turn 360°; participants were asked to stand on each leg and then on their toes for 10 seconds. We record number of steps off the line when walking 8 feet (2.4 meters) heel-to-toe; and Purdue pegboard and finger tapping. A composite measure of global motor function was constructed by converting the raw score from each of the motor measures to z scores using the mean (SD) from all participants at baseline and averaging. Separate summary measures of strength and performance were also developed.

A continuous composite measure of physical frailty was developed based on the four commonly used components of frailty, as previously described [58]. These include grip strength, timed 2.4 meter walk, body mass index based on measured height and weight, and fatigue based on two questions from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D). A dichotomous version was also developed for analyses.

Actigraphy and Sleep

Actigraphy was employed to provide objective measures of motion not subject to patient recall. The actigraph is a waterproof wristwatch-size battery-operated activity monitor (Actical, Phillips Respironics, Bend, OR) placed on the non-dominant wrist of each subject and worn 24 hours/day for up to 10 days. Since the device quantifies and records average movement over each 15 second (epoch) continuously 24 hours/day, these recordings include periods of activity (arousal) and non-activity (rest). Several measures are used to summarize activity including total daily activity, and intensity of daily activity [59]

The actigraphy data has also been used to extract indices of rest rest activity fragmentation as a proxy for sleep [60]. Further, it has been used to calculate acrophase (time of peak activity) and circadian phases [61].

Gait Belt

A small, light-weight whole body sensor, the size of a wrist watch, is worn on a neoprene belt around the waist during motor performance testing. The device contains 3 accelerometers and 3 gyroscopes (DynaPort MiniMod Modules, McRoberts BV). The Netherlands) A wide range of spatial-temporal gait measures can be derived from the data collected, augmenting traditional measures of time used to describe gait performances tested in the community-setting such as the 8' walk or the Timed Get-Up and Go [62].

Pulmonary Function

Pulmonary function was assessed with a hand-held spirometer as previously described [63]. Measures included forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), and peak expiratory flow (PEF) from which a composite measure was derived. Respiratory muscle strength was assessed using a hand-held device that contains a pressure sensitive transducer to measure maximal inspiratory and expiratory pressures from which a composite measure was derived [64].

Self Report Activities of Daily Living

Self-report measures assess the ability to live independently and perform basic and instrumental activities of daily living [65–67].

Experiential and Personality Risk Factors of Interest

Experiential factors include early- mid- and late-life (current) cognitive and physical activities, social engagement, social networks, and childhood adversity [31,56,68–72]. Affect includes measures of depressive symptoms [73,74]. Personality includes measures of neuroticism, extroversion, openness, agreeableness, conscientiousness, harm avoidance, novelty seeking, loneliness, and anxiety [75–78]. We assessed experiential well being with a measure of purpose in life [79,80]. Additional personality and well-being measures were added in 2010. Odor identification was assessed with the Brief Smell Identification Test [81]. We also assessed life space, an index of spatial mobility in the world [82].

Ante-Mortem Biological Specimens and Data

A blood sample is taken at each evaluation and aliquots of serum and plasma are stored in a −80°C freezer. Lymphocytes are extracted to provide a source of DNA for genetic studies, and cell lines have been created from more than 1000 participants. Lymphocytes are also cryopreserved for functional studies.

Serum and plasma are used to obtain laboratory studies (e.g., hemoglobin, creatinine). DNA has been used to characterize apolipoprotein E allele status (APOE) [83] and other genetic variants [84]. Recently, it has been used to generate genome-wide data [85].

Post-Mortem Biological Specimens

Staff is on-call 24 hours per day, seven days a week, to coordinate transportation of the body and perform the autopsies. The calvarium is opened, cerebrospinal fluid is removed, spun, aliquoted into separate nunc vials and frozen in a −80°C freezer. The brain is removed and weighed. The brainstem and cerebellum are dissected from the hemispheres and one hemisphere and the cerebellum are cut into 1 cm slabs in a plexiglass jig. The 1 cm slabs are frozen in a −80°C freezer and the remainder of the brain is placed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Digital pictures of the hemispheres and slabs are obtained at the time of autopsy. Beginning in 2007, the fixed hemisphere has undergone post-mortem imaging [86].

After paraformaldehyde fixation and post-mortem imaging, the fixed hemisphere is cut into 1 cm slabs, photographed and tissue blocks are dissected from specified brain regions (including hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, midfrontal cortex, superior frontal cortex, inferior temporal cortex, middle temporal cortex, inferior parietal cortex, primary occipital cortex, anterior basal ganglia, anterior thalamus, and midbrain) and paraffin embedded for subsequent histochemistry and immunocytochemistry. Gross features and pathology (e.g., atrophy, cerebrovascular disease) are described at the time of blocking, and blocks are obtained from all areas of visible pathology (e.g., infarcts, tumors) from direct observation or from the digital photographs. The remainder of the brain is transferred to a graded cryoprotectant solution (final solution of 20% glycerol and 2% DMSO in phosphate buffer) for long term storage at 4°C.

After the brain is removed, the entire spinal cord including cauda equina, dura, and dorsal root ganglia is removed using the standard posterior approach. Prior to turning the body, the most rostral aspect of the cervical cord is loosened from the spinal canal at the level of the foramen magnum (after brain removal) and is cut and removed separately to avoid pulling of the cord and consequent “toothpaste” artifact. The body is then turned and the entire spinal cord, cauda equina, dura, and dorsal root ganglia are removed. After removal, the length and diameter of the cord is measured and recorded, and each segment of the cord is dissected in order to obtain fresh frozen cord. The spinal cord is cut midway through the lumbar enlargement (L3-S1), as identified by enlarged motor rootlets, which approximates L4-5 levels. A 4 mm thick block of lumbar spinal cord is taken from both sides of this incision and is fixed. The rostral lumbar and caudal adjacent 0.4 cm are frozen. A similar procedure is used for the cervical and thoracic cord in order to obtain frozen slices of cord in the cervical enlargement and midthoracic regions. The remainder of the spinal cord is fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 to 72 hours and then transferred to cryoprotectant (glycerol, DMSO, and phosphate buffer) for storage in a 4°C refrigerator.

Bilateral tibial nerves are dissected and stored from all subjects. At autopsy most of the nerve is fixed in a solution of glutaraldehyde and paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer and water). After fixation, samples are stored in buffer at 4°C for future EM studies. A small segment of nerve is also fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde.

Two adjacent samples of 2.0 cm3 from the belly of each deltoid, quadriceps femoris, and the gastrocnemius muscles bilaterally for a total of 12 muscle samples are dissected. The choice of muscles was based on several considerations, including the likelihood that dysfunction would contribute to motor impairment, the availability of clinical measures of their function, and that the site of biopsy would not leave a visible scar which would preclude an open casket and wake following the procedure. Two 1.0 cm portions of muscle are oriented on cork in cross-section, placed in OCT, and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen insulated by isopentane. Frozen muscle is stored (in vials containing frozen water for hydration) at −80°C. The remainder of the muscle is fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2–3 days and embedded in paraffin.

Post-Mortem Data

The post-mortem neuropathologic evaluation includes a uniform structured assessment of AD pathology, cerebral infarcts, Lewy body disease, and other pathologies common in aging and dementia. The procedures follow those outlined by the pathologic dataset recommended by the National Alzheimer's Disease Coordinating Center (NACC) [87]. Pathologic diagnoses of AD use NIA-Reagan and modified CERAD criteria, and the staging of neurofibrillary pathology uses Braak Staging [88–90]. The location, size, and age of each macroscopic infarct are recorded as described [91]. Microscopic infarctions are identified on H&E stained sections; Lewy bodies are identified on alpha-synuclein immunostained sections [91].

Counts of neuritic plaques diffuse plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles based on silver stain from five brain regions are used to create a global measure of AD pathology [70]. Amyloid load and the density of paired helical filament tau (PHFtau) are determined in eight brain regions and summarized [70].

Statistical Approaches

The study design permits many types of analyses to be performed within a single dataset. The analyses address a wide range of issues related to the causes and consequences of common age related conditions, while controlling for demographics and other potential confounding variables. Analyses without neuropathologic indices are performed in the entire cohort. Thus, the temporal relation between a risk factor and clinical outcome is established in the entire cohort. This allows us to draw valid inferences from the cross-sectional associations with pathology.

Logistic regression is used in cross-sectional analyses examining the association of neuropathology to cognitive outcomes such as MCI and AD proximate to death [33]. Linear regression is used in cross-sectional analyses examining the relation of neuropathology to continuous outcomes such as level of cognition proximate to death [70]. Interaction terms are used in these models to examine whether the association of neuropathology with clinical outcomes varies by the level of a third factor [70].

Longitudinal time to event analyses use Cox proportional hazards models for dichotomous outcomes (e.g., incident AD, incident MCI) [92]. Recently, we have used models for discrete (tied) data [93]. Mixed models are used to examine the relation of risk factors to change in cognitive function over time [94]. These models assume that individuals follow the mean path of the group, conditional on a set of explanatory variables, except for random effects which allow for the initial level to be higher or lower and the rate of change to be faster or slower. Other paths of change can be modeled in other ways such as change point models [95].

Recently confirmatory factor analysis was used to develop latent cognitive and neuropathologic indices for use in Multiple-Indicator-Multiple-Cause (MIMIC) models [96].

FINDINGS

From November September of 1997 through November of 2011, 1,556 persons agreed to participate and the baseline clinical evaluation has been completed on 1,489. Of these, 1,088 (73.1%) are women, 1,307 (87.8%) are non-Hispanic white, the mean age is 80.1 years and the mean education is 14.4 years. 1,409 (94.6%) were without dementia following the baseline clinical evaluation. All clinical evaluation forms have been translated into Spanish and of 80 Hispanics, 63 are being tested in Spanish.

The overall follow-up of survivors approaches 95%. There have been 343 cases of incident MCI including 168 cases of incident amnestic MCI, and 250 cases of incident dementia including 238 cases of incident AD with or without a coexisting condition.

The autopsy rate exceeds 80% with 424 autopsies of 519 deaths (81.7%). Of these, 272 (64.2%) are women, 407 (96.0%) are non-Hispanic white, the average age at death is 88.5 and the interval from last evaluation to death is 10.6 months. The post-mortem interval is 8:07 hours:minutes. The summary clinical diagnoses have been completed for the first 418, of whom 136 (32.5%) were without cognitive impairment, 117 (28.0%) had MCI, 138 (33.0%) had probable AD, 18 (4.3%) had possible AD, and 9 (2.2%) had dementia due to another condition. The diagnostic pathologic evaluation has been completed for the first 402 (94.8%). Of the 424 persons with a brain autopsy, the spinal cord has been obtained on 411 (96.9%).

Relation of Motor Function to Cognition, Disability and Death

In cross-sectional analyses, a global measure of parkinsonism and individual parkinsonian signs were related to a global measure of cognition and specific cognitive abilities [97]. Similarly, parkinsonian signs were also related to MCI [40]. Among persons with MCI, lower extremity function was also related to disability [98].

In longitudinal analyses, level of physical frailty and change in physical frailty over time were associated with risk of incident AD and incident MCI, and to the rate of cognitive decline [99,100]. Parkinsonian signs were also related to risk of AD [101]. Likewise, level of baseline global cognition and five cognitive abilities were also associated with the development of incident mobility impairment based on gait speed and loss of the ability to ambulate as well as the annual rate of decline of mobility [102].

Further, change over time in cognition, an overall measure of motor function, physical frailty, parkinsonian signs, and an overall measure of physical activity with actigraphy were all related to risk of death [57,58,95,101,103]. Parkinsonian signs were also related to functional disability and risk of falls [104,105].

We also conducted change point models to determine the timing of onset of cognitive decline prior to incident AD and MCI [106]. Compared to persons who were not diagnosed with AD or MCI, cognitive decline started a number of years prior to disease diagnosis.

Relation of Risk Factors to Cognitive and Motor Outcomes, Disability and Death

Cognitive, Physical Activities, Social Engagement, Loneliness and Life Space

Participation in cognitively stimulating activities across the life course was associated with level of cognition [56,107,108]. Both past and current cognitive activities were associated with a reduced risk of AD and with a slower rate of cognitive decline, especially episodic memory, semantic memory, and perceptual speed, in analyses that controlled for baseline level of cognition [31]. Further, current activities were associated with AD risk after controlling for past activities. The effect of late life cognitive activities appears to be stronger than the effect of education on building cognitive reserve [109]. Current activities were also associated with incident MCI. We used dual change models to document that change in cognitive activities precede changes in cognition [110]. Finally, cognitive activities were not related to measures of neuropathology suggesting that lower cognitive activities were not likely a consequence of the accumulation of pathology.

Physical activity by self report was associated with a slower rate of decline in motor function [68]. This association was unchanged after controlling for leg strength [111]. Physical activity was associated with a reduced risk of incident disability, a finding that persisted when controlling for muscle strength [111,112]. Physical activity and greater rest activity fragmentation assessed by actigraphy were associated with cognition [113,114], incident AD and change in cognition [115], and with decline in motor function [116]. In longitudinal analyses, total daily physical activity was associated with risk of death [103].

Social engagement, specifically social activity and social support, though not social networks, was associated with global cognition and diverse measures of specific cognitive domains, especially perceptual speed [69]. Late life social activities were also related to a slower rate of decline in cognitive and motor function even after controlling for physical and cognitive activities [118–120]. Social engagement was also related to incident disability [121]. The related construct of loneliness was also associated with risk of AD and rate of cognitive decline, even after controlling for the effect of social activity [119]. It was also associated with the rate of decline in motor function [122].

Finally, greater life space was associated with better cognitive and motor function [123], and it was associated with a lower risk of incident AD, incident MCI, and cognitive decline, as well as risk of death [124,125].

Anxiety-Related Traits: Neuroticism, Anxiety, Childhood Adversity, and Harm Avoidance

Neuroticism was associated with an increased risk of AD and with a more rapid rate of cognitive decline among persons without dementia, and risk of MCI and change in cognition among persons without dementia or MCI [126,127]. Interestingly, the association was most robust for episodic memory and executive abilities (i.e., working memory, perceptual speed) [128]. Neuroticism is a broad trait. Of its facets, anxiety and vulnerability to stress were most strongly related to cognitive decline [128]. Neuroticism was also associated with change in motor function [129]. Anxiety is also associated with risk of dementia [128]. Interestingly, childhood adversity, in particular emotional neglect and parental intimidation, was associated with neuroticism [72].

Harm avoidance, a trait associated with apprehensiveness and behavioral inhibition, was associated with cognitive decline and risk of AD [130]. It was also associated with measures of disability [131].

Medical Conditions

In cross-sectional analyses, low hemoglobin was associated with lower cognition [132], and in longitudinal analyses it was associated with risk of incident AD [133]. In longitudinal analyses, lower kidney function was associated with more rapid rate of cognitive decline [134]. Diabetes was associated with poorer cognitive function and more parkinsonism [42,135–137]. Vibratory function was also associated with parkinsonian gait after controlling for diabetes [138]. Musculoskeletal pain was associated with incident disability [41]. Finally, inflammatory markers were associated with cortical thinning on ante-mortem neuroimaging [139].

Apolipoprotein E Allele Status (APOE) and Other Genetic Variants

The APOE ε4 allele was associated with a greater rate of decline in motor function [83]. CR1 and PICALM were also associated with cognitive decline and AD risk [84]. CR1 was also associated with amyloid angiopathy [140]. The 1405V CEPT polymorphism was was also associated with risk of AD and cognitive decline [141]. Genome-wide data are available and have been used in a number of collaborative projects [85,142–148].

Well-Being (Purpose in Life)

Purpose in life was associated with a reduced risk of incident AD, incident MCI and a slower rate of decline in cognitive function among persons without dementia or MCI [93]. Purpose in life was also associated with a reduced risk of incident disability and risk of death [80,149].

Odor Identification

Loss of odor identification was associated with a greater rate of cognitive decline and an increased risk of MCI [150,151]. Odor identification was also associated with progression of parkinsonian signs, primarily parkinsonian gait [152]. Finally, it was associated with risk of death [153].

Respiratory Muscle Strength and Pulmonary Function

Respiratory muscle strength was associated with the rate of change in mobility even after controlling for leg strength and physical activity [63]. In a subsequent study, we found that respiratory muscle strength, leg strength, physical activity as well as pulmonary function all made relatively independent contributions to the development of mobility disability [64]. In contrast, we found that pulmonary function linked both appendicular and respiratory muscle strength with the risk of death [117].

Relation of Common Neuropathologic Indices to Clinical AD, MCI, and Level of Cognition AD, MCI, and Level of Cognition

Alzheimer's Disease Pathology

About 90% of persons meeting clinical criteria for AD also met pathologic criteria for the disease [32,33]. However, about half of persons with MCI also met pathologic criteria for AD and a third of those without cognitive impairment met pathologic criteria for AD [33]. Further, among this group of very high functioning individuals, the presence of AD pathology was associated with deficits in episodic memory [154]. Interestingly, self-report memory complaints were also related to measures of AD pathology in analyses that controlled for depression and chronic disease [155].

Cerebrovascular Disease

Persons with dementia were most likely to have had cerebral infarcts and those with MCI had an intermediate number of infarctions compared to those without cognitive impairment [33]. Interestingly, while infarcts were related to all cognitive abilities, in analyses controlling for AD pathology, both infarcts overall and subcortical infarcts were strongly related to measures of episodic memory [156]. Further, AD pathology and cerebral infarcts had an additive effect on the odds of dementia. In this community based study, cerebrovascular disease was found to be more common than in clinic based series [91,157]

Lewy Bodies

Lewy bodies were most common in persons with dementia and intermediate among those with MCI [33]. In this community based study, Lewy bodies were found to be less common than in clinic based series [91]

Mixed Pathologies

The combination of AD pathology with cerebral infarcts or Lewy bodies is so common that mixed pathologies are the most common cause of dementia [158]. They are also as common as “pure” AD pathology as a cause of probable AD [33]. In addition, mixed pathology accounts for a substantial proportion of cases of both amnestic and non-amnestic MCI [33]. Consistent with this, all three pathologies are strongly related to multiple cognitive abilities, including episodic memory [159].

Relation of Common Neuropathologic Indices to Motor Function and Odor Identification

Parkinsonian signs were related to AD pathology, cerebrovascular disease, Lewy bodies and nigral degeneration [160]. Physical frailty was also directly related to AD pathology and the association was similar in persons both with and without dementia [161]. Further, among those without cognitive impairment, impaired odor identification was related to both AD pathology and Lewy bodies [162,163]. Unlike APOE and other polymorphisms for which there is considerable evidence suggesting that it leads to the accumulation of AD pathology, the findings with parkinsonian signs, frailty and odor identification suggest that these clinical findings may be early signs of disease [164].

Relation of Risk Factors to Neuropathologic Indices (Table 3)

Table 3.

Relation of Risk Factors to Neuropathologic Indices

| Risk Factor | Association with Neuropathology | Reduced Association of Pathology with Cognition |

|---|---|---|

| APOE ε4 | AD | |

| APOE ε2 | AD | |

| CR1 | AD | |

| CEPT | AD | |

| PICALM | ||

| Neuroticism | ||

| Anxiety | ||

| Vulnerability to stress | ||

| Social networks | AD | |

| Purpose in life | AD | |

| Processing resources | AD | |

| Cognitive activity | ||

| Loneliness | ||

| Oder identification | AD, Lewy bodies | |

| Grip strength | AD | |

| Physical frailty | AD | |

| Parkinsonian signs | AD, Infarcts, Lewy bodies |

The APOE ε4 allele was associated with greater AD pathology and the ε2 allele was associated with less AD pathology [165]. Similar findings were seen with CR1 and CEPT suggesting that these polymorphisms are also associated with AD in part through an association with AD pathology [83,141]. A number of other polymorphisms were related to AD pathology in a candidate gene study [166–168].

While we did not find a main effect of social networks on either AD risk or neuropathology, we did find that social networks modified the relation of AD pathology to cognition [169]. In other words, AD pathology had much less effect on cognition among persons with larger networks. In further analyses, the effect was most strongly associated with tangle formation. We conjectured that social networks may be a proxy for social cognition and hypothesized that some types of cognition might modify the relation of AD pathology to other forms of cognition. In keeping with this idea, we found that processing resources reduced the effect of AD pathology on episodic memory, semantic memory, and visuospatial ability [170]. Further, purpose in life reduced the effect of AD pathology on the rate of change in cognition over multiple years prior to death [171].

Two risk factors for AD, cognitive activities and loneliness, were not related to AD pathology nor did they modify the relation of AD pathology to cognition [31,119]. Similarly, neuroticism and anxiety were unrelated to measures of neuropathology [128]. Thus, these factors must influence AD risk via alternate mechanisms.

Selected Other Study Findings

Studies of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI)

MCI was associated with a substantially increased risk of developing AD and a greater rate of cognitive decline [172]. Persons with MCI had entorhinal cortex and hippocampal atrophy and disruption of parahippocampal white matter fibers [173]. They also had reductions of fractional anisotropy in posterior white matter regions [174]. Finally, among persons with MCI, both baseline entorhinal cortex hippocampal volume and rate of change in entorhinal cortex and hippocampal volume are associated with risk of AD [175–177]. MCI was also associated with changes in resting state fMRI [178].

Post-Mortem Neuroimaging

Post-mortem imaging is being performed to better understand the relation of brain pathology to MRI changes. We first conducted a study of repeated post-mortem images over a six month period to characterize changes in T2 values and identify the optimal timing of imaging [86]. Subsequently, we have started to characterize the relation of neuropathology to structural changes beginning with the hippocampal formation [179].

Behavioral Economics, Neuroeconomics, and Decision Making

In 2008, a behavior economics and decision making survey was added to the Memory and Aging Project. These data are just beginning to mature. We have shown that among persons without dementia, lower cognition is associated with greater risk aversion [180]. Using resting state fMRI, we also showed regional differences associated with risk aversion [181].

Other Findings

The Rush Memory and Aging Project has contributed biologic specimens and data to support a range of other efforts [182,183]. Some efforts are still maturing including studies of nutrition and anti-phospholipid antibodies, synaptic proteins, TDP-43, DNA methylation, histone acetylation (H3K9Ac), RNA microarray, and next generation RNA-Sequencing.

DISCUSSION

Data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project has generated more than 125 peer-reviewed publications to date on a wide range of issues related to aging and AD. The main find ings can be summarized into four major headings: 1) evidence of common causation of loss of cognitive, motor and olfactory function; 2) continuum of cognition and neuropathology from normality to MCI to dementia; 3) implications of mixed pathologies; 4) evidence of neural reserve.

Common Causation of Loss of Cognitive, Motor and Olfactory Function

Cognitive and motor abilities are generally considered unique and separate functional outputs of neural systems. However, to some extent they rely on similar underlying neural processes. For example, motor function, especially skilled movements such as those required to produce language and complex movements, require motor programs which can be impaired and lead to loss of learned motor abilities despite intact strength and coordination. A unique feature of the Memory and Aging Project is the detailed longitudinal data on both cognitive and motor function. The latter includes measures of parkinsonian signs, an overall measure of motor function based on strength and performance measures, a measure of physical frailty that includes measures of muscle structure and function as well as walking speed, all of which were related to cognitive outcomes. Other studies have also shown both cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between cognitive and motor function [184–194]. In addition, several risk factors, including APOE, social activity, loneliness, neuroticism, respiratory function, renal function and diabetes were related to both cognitive and motor abilities in either cross-sectional or longitudinal analyses, consistent with some prior studies [195]. Together, these findings provide strong evidence of common causation of decline in cognitive and motor abilities.

Interestingly, odor identification was also related to AD risk and change in cognitive function, consistent with prior research [196,197], and with decline in motor function suggesting that this too might have a common causation. This was supported by the clinical pathologic analyses which find that measures of AD pathology were related to olfactory function, parkinsonian signs, frailty, and strength. Lewy bodies were also related to odor identification and parkinsonian signs. Given that it is highly unlikely that parkinsonian signs, frailty, strength and odor identification cause the accumulation of neuropathology, it is likely the case that neuropathology leads to parkinsonian signs, frailty, loss of strength, and impaired odor identification. Thus, changes in motor function and odor identification may be early signs of AD pathology and may appear prior to the development of not only clinical AD but also prior to the onset of MCI.

Continuum of Cognition and Neuropathology from Normality to MCI to Dementia

Our data suggest that there is a continuum of cognitive change accompanied by gradual accumulation of neuropathology with no precise clinical or neuropathologic cut-point that distinguishes dementia from MCI or MCI from normality. This is similar to many other common chronic conditions of aging such as osteoporosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. These diseases have an insidious onset over years and possibly decades and the demarcation between the presence and absence of the disease is determined by consensus criteria based on imperfect data. For some conditions, a designation of intermediate between normality and disease is employed, as in pre-hypertension and osteopenia. This is analogous to the use of MCI as a condition intermediate between normality and dementia. Overall, the data suggest that much of cognitive decline among persons without dementia is not the result of a normative aging process but rather the result of the common neuropathologies that ultimately result in MCI and dementia [198]. This conclusion is consistent with reports that AD pathology is common among persons with MCI [199–202] and some report AD pathology among persons without cognitive impairment [203–208]. We related AD pathology to subtle decrements in episodic memory among persons without cognitive impairment [154]. These data are consistent with what is being reported with amyloid imaging agents among persons without dementia but are based on quantitative neuropathologic data [209,210]. Overall, the data suggest that there is unlikely to be qualitatively meaningful biologic distinctions between MCI and AD, regardless of the definition used. The data strongly support the recent revised criteria of AD as beginning with a pathophysiologic process and evolving to MCI due to AD and finally to AD dementia [211–213].

Implications of Mixed Pathologies for the Prevention of AD

Clinical and post-mortem data from the Memory and Aging Project offer an unprecedented opportunity to investigate biologic pathways linking risk factors to clinical disease among a socioeconomically diverse cohort of older men and women. This investigation involves first understanding the relation of pathological indices to clinical AD and MCI. We found that AD pathology with other common pathologies, in particular cerebrovascular disease and Lewy bodies, are the most common cause of clinically probable AD and a common cause of MCI and amnestic MCI. These data are consistent with and extend findings from several other clinical-pathologic studies [214–224]. The findings raise the possibility that some risk factors for clinical AD are likely to be risk factors for pathologies other than AD. For example, APOE is strongly related to AD pathology and CR1 and CEPT less so. Thus, these polymorphisms appear to be related to AD in part through an association with AD pathology. Understanding the mechanism linking these polymorphisms to amyloid deposition would be a useful for developing strategies for interventions. By contrast, several other risk factors for clinical AD were not directly related to measures of AD pathology. Thus, they must work through an alternate pathway.

The data also shed light on the important role of mixed pathologies in the development of dementia such that the elimination of mixed disease, such as cerebrovascular disease will result in less clinically diagnosed AD. This has important implications for our conceptuatlization of AD as well as vascular cognitive impairment [225].

Evidence of Neural Reserve

A major goal of the Rush Memory and Aging Project is to identify factors associated with neural reserve, i.e., factors that increase the ability of the brain to tolerate the pathology of AD without manifesting clinical signs of cognitive impairment [226]. In some respects, mixed pathology can be conceptualized in terms of neural reserve; that is, the presence of cerebrovascular disease and Lewy bodies reduce the ability of the brain to tolerate any given amount of AD pathology making it more likely that it will lead to cognitive impairment and dementia. Thus, the prevention of cerebrovascular disease and Lewy body disease will reduce the numbers of persons meeting clinical criteria for AD.

It is now apparent that many other factors can increase or decrease neural reserve. For example, we found that social networks modified the association of AD pathology to cognition such that AD pathology was less likely to be associated with cognitive impairment among persons with large compared to those with small social networks. Similar finding were observed for processing resources and purpose in life. These data provide strong evidence that some experiential factors can alter the clinical expression of AD pathology. Other studies have reported similar findings with education and other indices using measures of AD pathology and amyloid imaging [227–232].

By contrast, several other factors associated with incident AD had effects that were separate from any of the three common causes of dementia. These include cognitive activity, neuroticism (especially the facets of anxiety and vulnerability to stress), and loneliness. Thus, these factors alter the likelihood that AD pathology will lead to clinical disease. The biologic mechanisms underlying the association of these traits with clinical disease are unknown. However, identifying these pathways is important as an understanding of pathways would provide new targets for therapeutic interventions. A variety of efforts are ongoing in the Memory and Aging Project aimed at identifying additional therapeutic targets including epigenome-wide DNA methylation and histone acetylation studies, RNA expression studies, and proteomics.

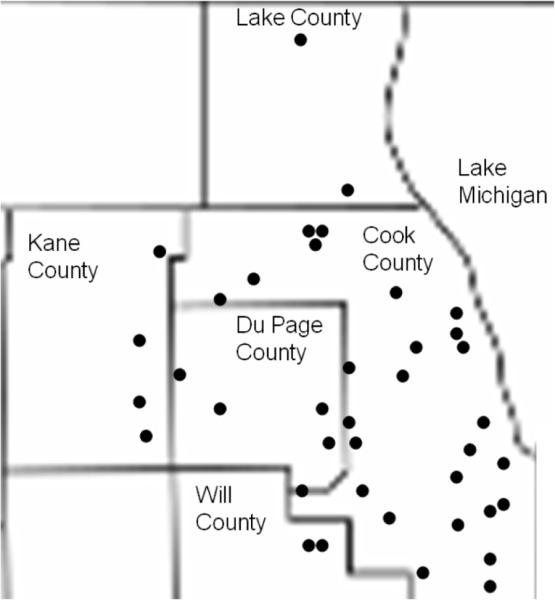

Overall Model Summarizing Findings Fig. (3)

Fig. (3).

Overview of clinical pathologic relationships reported in the Rush Memory and Aging Project through November 2010.

Fig. (3) presents an overview of selected findings to date. The model highlights the important role of mixed pathology and neural reserve in the development of clinical AD. It illustrates that some risk factors such as APOE, CR1, and CEPT lead to clinical AD in part through an association with AD pathology. However, it also shows that some other factors associated with the development of clinical AD such as parkinsonian signs, grip strength, frailty, and odor identification, are not risk factors at all. Rather they are likely to be early signs of AD and other pathology that manifest prior to the onset of dementia and in some cases prior to the onset of MCI. It is conceivable that these non-cognitive manifestations could be the sole clinical manifestation of AD pathology in some persons. By contrast, we have not been able to directly relate psychological and experiential factors to any known type of neuropathology. It is interesting that we have only identified genetic risk factors associated with AD pathology, and an ongoing genome-wide association study is examining additional genomic variants associated with cognitive decline and neuropathologic indices [148]. These observations have led us to consider a model whereby AD pathology is primarily under the control of genomic variation, whereas experiential and psychological factors primarily affect how the brain responds to the accumulation of pathology, i.e., neural or cognitive reserve. These findings are similar to results found in the Religious Orders Study [233–236].

The figure also illustrates decision making as a complementary outcome to cognitive, motor, and olfaction. While data are not yet available, we hypothesize that impaired decision making is likely to be a consequence of common neuropathologies.

Integral to the study design is that once a relationship between a risk factor and cognitive loss is identified, the risk factor must be related to changes in the structural or functional elements that subserve cognition. It is clear from Fig. (3) that there are many risk factors for which the biologic signature has not yet been identified. We are currently investigating the potential for a number of indices to mediate these associations. There are two ongoing epigenome-wide studies of brain tissue and peripheral blood lymphocytes. There are also ongoing RNA expression (microarray and next generation RNA sequencing), proteomic and metabolomic studies searching for novel biologic pathways linking risk factors to clinical disease.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

The study has several strengths. Individuals known to be free of dementia or free of MCI at baseline are followed for the development of incident disease and cognitive decline. There is a large sample size and a relatively long duration of follow-up with repeated measures of cognition and large number of persons with incident disease. The follow-up rate of survivors and the autopsy rates are very high, which reduces the biases that occur when persons drop out of longitudinal studies or when autopsy is not obtained. Structured procedures ensure uniformity of diagnostic decisions across time and space. Examiners are blinded to previously collected data, which further reduces bias. The study enrolls participants with a wide range of experiential factors in order to facilitate investigating the role of these factors in the development of neural reserve. Finally, a unique aspect of the study is that both clinical and pathologic data collection procedures are similar in many respects to the Religious Orders Study, which allows data to be merged for analyses that may have small to moderate effects [32,33,123,154,159,165,166].

The study also has limitations. There are relatively few racial and ethnic minorities, which limits the ability to examine associations across race and ethnicity. However, clinical data collection procedures are similar in many respects to the Minority Aging Research Study whic allows data to be merged to examine potential racial differences [80, 102, 124, 125, 136, 237]. In addition, this is a volunteer cohort that has agreed to autopsy at study entry. Thus, participants may not be representative of the general population of older persons and similar types of studies will need to be done in cohorts with a greater proportion of racial and ethnic minorities, and in population based cohorts.

Table 2.

Factors Related to Loss of Cognition and Motor Function

| Risk Factor | AD | Cog Dec (1) | MCI | Cog Dec (2) | Motor Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parkinsonian signs | X | X | NA | ||

| Physical frailty | X | X | X | X | NA |

| Muscle strength | X | X | X | X | X |

| MCI | X | NA | NA | NA | |

| Cognitive activity | X | X | X | ||

| Social activity | X | X | X | ||

| Physical activity | X | X | X | ||

| Neuroticism | X | X | X | X | X |

| Anxiety | X | X | |||

| Vulnerability to stress | X | X | |||

| Loneliness | X | X | X | ||

| Harm avoidance | X | X | X | X | |

| Purpose in life | X | X | X | X | |

| Life space | X | X | X | X | |

| Odor identification | X | X | X | X | X |

| APOE | X | ||||

| CR1 | X | ||||

| PICALM | X | ||||

| CEPT | X | X | |||

| Hemoglobin | X | X | |||

| Cognition | NA | NA | NA | NA | X |

cognitive decline among persons without dementia at baseline.

cognitive decline among persons without dementia or MCI at baseline.

NA not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the older men and women from across northeastern Illinois participating in the Rush Memory and Aging Project.

We thank Tracy Colvin, MPH; Tracey Nowakowski, MS; Tracy Faulkner, MS; Barbara Eubeler, Karen Lowe-Graham, MS, and Karen Skish, MS, PA(ASCP) MT, for study recruitment and coordination, and John Gibbons, MS and Greg Klein for data management, and the staff of the Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center.

Work presented here was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging: R01AG17917, R01AG15819, R01AG22018, R01AG24480, R01AG24871, R01AG26916, R01AG33678, R01AG34374, R21AG30765, K23AG23040, the Illinois Department of Public Health, the Elsie Heller Brain Bank Endowment Fund, and the Robert C. Borwell Chair of Neurological Sciences.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST None declared.

REFERENCES

- [1].Trends in Aging – United States and Worldwide. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:101–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer's disease in the US population: Prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurology. 2003;60:1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Brookmeyer R, Gray S, Kawas C. Projections of Alzheimer's disease in the United States and the public health impact of delaying disease onset. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1337–1342. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sloane PD, Zimmerman S, Suchindran C, et al. The public health impact of Alzheimer's disease, 2000-2050: potential implication of treatment advances. Annu Rev Public Health. 2002;23:213–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Selkoe DJ. Defining molecular targets to prevent Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:192–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Haan MN, Wallace R. Can dementia be prevented? Brain aging in a population-based context. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.122951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D. Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–44. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Khachaturian ZS. Diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Arch Neurol. 1985;42:1097–105. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1985.04060100083029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Katzman R, Terry R, DeTeresa R, Brown T, Davies P, Fuld P, et al. Clinical, pathological, and neurochemical changes in dementia: a subgroup with preserved mental status and numerous neocortical plaques. Ann Neurol. 1988;23:138–44. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Crystal HA, Dickson DW, Sliwinski MJ, Lipton RB, Grober E, Marks-Nelson H, et al. Pathological markers associated with normal aging and dementia in the elderly. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:566–573. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Morris JC, Storandt M, McKeel DW, Jr, et al. Cerebral amyloid deposition and diffuse plaques in “normal” aging: evidence for pre-symptomatic and very mild Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1996;46:707–719. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hulette CM, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Murray MG, Saunders AM, Mash DC, McIntyre LM. Neuropathological and neuropsychological changes in “normal” aging: evidence for preclinical Alzheimer disease in cognitively normal individuals. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:1168–1174. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199812000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Davis DG, Schmitt FA, Wekstein DR. Markesbery WR. Alzheimer neuropathologic alterations in aged cognitively normal subjects. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:376–388. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199904000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Krieger BP Respiratory failure in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 1994;10:103–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Epstein M. Aging and the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:1106–22. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V781106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Matsuzaki S, Onda M, Tajiri T, Kim DY. Hepatic lobar differences in progression of chronic liver disease: correlation of asialoglyco-protein scintigraphy and hepatic functional reserve. Hepatology. 1997;25:828–32. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lakatta EG. Cardiovascular reserve capacity in healthy older humans. Aging. 1994;6:213–23. doi: 10.1007/BF03324244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hornick TR, Kowal J. Clinical epidemiology of endocrine disorders in the elderly. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1997;26:145–63. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70238-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Scott RT, Jr, Hofmann GE. Prognostic assessment of ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril. 1995;63:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Necas E, Sefc L, Brecher G, Bookstein N. Hematopoietic reserve provided by spleen colony-forming units (CFU-S) Exp Hematol. 1995;23:1242–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhang MY, Katzman R, Salmon D, et al. The prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer's disease in Shanghai, China: impact of age, gender, and education. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:428–37. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Stern Y, Gurland B, Tatemichi TK, Tang MX, Wilder D, Mayeux R. Influence of education and occupation on the incidence of Alzheimer's disease. JAMA 6. 271:1004–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Graves AB, Mortimer JA, Larson EB, Wenzlow A, Bowen JD, McCormick WC. Head circumference as a measure of cognitive reserve. Association with severity of impairment in Alzheimer's disease. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169:86–92. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schofield PW, Logroscino G, Andrews HF, Albert S, Stern Y. An association between head circumference and Alzheimer's disease in a population-based study of aging and dementia. Neurology. 1997;49:30–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Stern Y, Alexander GE, Prohovnik I, Mayeux R. Inverse relationship between education and parietotemporal perfusion deficit in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1992;32:371–5. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Stern Y, Alexander GE, Prohovnik I, et al. Relationship between lifetime occupation and parietal flow: implications for a reserve against Alzheimer's disease pathology. Neurology. 1995;45:55–60. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Alexander GE, Furey ML, Grady CL, et al. Association of premorbid intellectual function with cerebral metabolism in Alzheimer's disease: implications for the cognitive reserve hypothesis. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:165–72. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Coffey CE, Saxton JA, Ratcliff G, et al. Relation of education to brain size in normal aging: implications for the reserve hypothesis. Neurology. 1999;53:189–96. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Mendes de, Leon CF, Bienias JL, Wilson RS. The Rush Memory and Aging Project: Study design and baseline characteristics of the study cohort. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:163–175. doi: 10.1159/000087446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lindsted KD, Fraser GE, Steinkohl M, Beeson WL. Healthy volunteer effect in a cohort study: temporal resolution in the Adventist Health Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:783–790. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wilson RS, Scherr PA, Schneider JA, Tang Y, Bennett DA. The relation of cognitive activity to risk of developing Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 2007;69:1911–20. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271087.67782.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Aggarwal NT, et al. Decision rules guiding the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease in two community-based cohort studies compared to standard practice in a clinic-based cohort study. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;27:169–176. doi: 10.1159/000096129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. Neuropathology of probable AD and amnestic and non-amnestic MCI. Annals of Neurology. 2009;66:200–208. doi: 10.1002/ana.21706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Roman GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, et al. Vascular dementia: Diagnostic criteria for research studies - Report of the NINDSAIREN International Workshop. Neurology. 1993;43:250–260. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Langston JW, Widner H, Goetz CGT, et al. Core Assessment Program for Intracerebral Transplantations (CAPIT) Movement Disord. 1992;7:2–13. doi: 10.1002/mds.870070103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Robins LN, Helzer JE, Ratcliff KS, Seyfried W. Validity of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, II: DSM-III diagnoses. Psychol Med. 1982;12:855–870. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700049151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wilson RS, Weir DR, Leurgans SE, et al. Sources of variability in estimates of the prevalence of Alzheimer's disease in the United States. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2011;7:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Weir DR, Wallace RB, Langa KM, et al. Reducing case ascertainment costs in US population studies of Alzheimer's disease, dementia, and cognitive impairment – Part 1. Alzheimer's & Dementia 7. 2011:94–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].McKeith IG, Perry EK, Perry RH. Report of the second dementia with Lewy body international workshop: diagnosis and treatment. Consortium on Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Neurology. 1999;53:902–905. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.5.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Aggarwal NT, et al. Parkinsonian signs in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2005;65:1901–1906. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000188878.81385.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Buchman AS, Shah RC, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. Musculoskeletal pain and incident disability in community-dwelling elders. Arthritis Care & Research. 2010;62:1287–1293. doi: 10.1002/acr.20200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Arvanitakis Z, Wilson RS, Li Y, Aggarwal NT, Bennett DA. Diabetes and function in different cognitive systems in older persons without dementia. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:560–565. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: A practical method for grading the mental state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised manual. Psychological Corporation; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Albert MS, Smith LA, Scherr PA, et al. Use of brief cognitive tests to identify individuals in the community with clinically-diagnosed Alzheimer's disease. Intl J Neurosci. 1991;57:167–178. doi: 10.3109/00207459109150691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wilson RS, Beckett LA, Barnes LL, et al. Individual differences in rates of change in cognitive abilities of older persons. Psychology and Aging. Psych & Aging. 2002;17:179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Morris J, Heyman A, Mohs R, et al. The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer's disease (CERAD). Part. Clinical and neruopsychological assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1989;39:1159–1165. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kaplan EF, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. The Boston Naming Test. Lea & Febiger; Philadelphia: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Cooper JA, Sagar HJ. Incidental and intentional recall in Parkinson's disease: An account based on diminished attentional resources. J Clin Exper Neuropsychol. 1993;15:713–731. doi: 10.1080/01688639308402591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test manual-revised. Western Psychological; Los Angeles: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Ekstrom RB, French JW, Harman HH, Dermen D. Manual for kit of factor-referenced cognitive tests. Educational Testing Service; Princeton: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Trenerry MR, Crosson B, DeBoe J, Leber WR. The Stroop Neuropsychological Screening Test. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Benton AL, Varney N, Hamsher KD, et al. Visuospatial judgment-A clinical test. Arch Neurol. 1978;35:364–367. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1978.00500300038006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Raven JC, Court JH, Raven J. Standard progressive matrices-1992 edition; Raven manual:Section 3. Oxford Psychologists Press; Oxford: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Goodglass H, Kaplan E. The Assessment of Aphasia and Related Disorders. Lea & Febiger; Philadelphia: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Assessment of lifetime participation of cognitively stimulating activities. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2003;25:634–642. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.5.634.14572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Change in motor function and risk of mortality in older persons. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2007;55:11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Change in frailty and risk of death in older persons. Experimental Aging Research. 2009;35:61–82. doi: 10.1080/03610730802545051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Bennett DA. Total daily activity is associated with cognition in older persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:697–701. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31817945f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Lim ASP, Yu L, Costa MD, et al. Quantification of the fragmentation of rest-activity patterns in elderly individuals using a state transition analysis. Sleep. 2011;34:1569–1581. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Lim AS, Saper CB, Buchman AS, Bennett DA, DeJager PL. A common genetic variant near PER1 is associated with objectively measured circadian phase in humans. Ann Neurol. 2010:S74. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Mirelman A, Weiss A, Buchman AS, Bennett DA, Hausdorff J. Potential utility of using a body-worn sensor in the community-setting to augment the assessment of mobility in cohort studies of aging. 64th Annual Meeting of the Gerontological Society of America; Boston, MA. November 20, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [63].Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Shah RC, Bennett DA. Respiratory muscle strength predicts decline in mobility in older persons. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31:174–180. doi: 10.1159/000154930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Leurgans SE, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Pulmonary function, muscle strength, and incident mobility disability in old age. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2009;6:581–587. doi: 10.1513/pats.200905-030RM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Katz S, Akpom C. A measure of primary sociobiological functions. Int J Health Serv. 1976;6:493–508. doi: 10.2190/UURL-2RYU-WRYD-EY3K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Rosow I, Breslau N. A Guttman health scale for the aged. J Gerontol. 1966;21:556–559. doi: 10.1093/geronj/21.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Higher level of physical activity is associated with slower motor decline in older persons. Muscle & Nerve. 2007;35:354–362. doi: 10.1002/mus.20702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Krueger KR, Wilson RS, Kamenetsky JM, Barnes LL, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Social engagement and cognitive function in old age. Experimental Aging Research. 2009;35:45–60. doi: 10.1080/03610730802545028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Arnold SE, Tang Y, Wilson RS. The effect of social networks on the relation between Alzheimer's disease pathology and level of cognitive function in old people: a longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet Neurology. 2006;5:406–412. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Wilson RS, Kreuger KR, Arnold SE, et al. Childhood adversity and psychosocial adjustment in old age. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14:307–315. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000196637.95869.d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. J Aging Hlth. 1993;5:179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- [75].Costa PT, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- [76].CloningerC R, Przybeck TR, Svrakic DM, Wetzel RD. The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI): A guide to its development and use. Center for Psychobiology of Personality; St. Louis, MO: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- [77].de Jong Gierveld J, Kamphuis FH. The development of a Rasch-type loneliness scale. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1985;9:289–299. [Google Scholar]

- [78].Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (form Y) Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- [79].Ryff CD, Keyes CL. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:719–727. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:574–579. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181a5a7c0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Doty RL, Marcus A, Lee WW. Development of the 12-item Cross-Cultural Smell Identification Test (CC-SIT) Laryngoscope. 1996;106:353–356. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199603000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].May D, Nayak US, Isaacs B. The life-space diary: A measure of mobility in old people at home. International Rehabilitation Medicine. 1985;7:182–186. doi: 10.3109/03790798509165993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Beck T, Kelly JF, Bennett DA. The presence of apolipoprotein E ε4 allele is associated with an increased rate of motor decline in older persons. Alzheimer's Disease & Associated Disorders. 2009;23:63–69. doi: 10.1097/wad.0b013e31818877b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Chibnik LB, Shulman JM, Leurgans SE, et al. The Alzheimer's susceptibility locus CR1 is associated with increased amyloid plaque burden and age-related cognitive decline. Annals of Neurology. 2011;69:560–569. doi: 10.1002/ana.22277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Walter S, Atzmon G, Demerath EW, et al. A genome-wide association study of aging. Neurobiology of Aging. 2011;32:2109.e15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Dawe RJ, Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Vasireddi SK, Arfanakis K. Post-mortem MRI of human brain hemispheres: T2 relaxation times during formaldehyde fixation. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2009;61:810–818. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Honig LS, Kukull W, Mayeux R. Atherosclerosis and AD: analysis of data from the US National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center. Neurology. 2005;64:494–500. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150886.50187.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].The National Institute on Aging, Reagan Institute Working Group on Diagnostic Criteria for the Neuropathological Assessment of Alzheimer's Disease Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:S1–S2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Mirra SM, Hart MN, Terry RD. Making the Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease. A Primer for Practicing Pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993;117:132–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological staging of AD-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Schneider JA, Aggarwal NT, Barnes LL, Boyle PD, Bennett DA. The neuropathology of older persons with and without dementia from community vs. clinic cohorts. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2009;18:691–701. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Cox DR. Regression models and life tables (with discussion) J Soc Stat Soc B. 1972;74:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- [93].Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of incident Alzheimer's disease among community-dwelling older persons. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:304–10. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Laird N, Waire J. Random effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Wilson RS, Beck TL, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Terminal cognitive decline: Accelerated loss of cognition in the last years of life. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:131–137. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31803130ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Jöreskog KG, Goldberger AS. Estimation of a model with multiple indicators and multiple causes of a single latent variable. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1975;70:631–639. [Google Scholar]

- [97].Fleischman DA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Parkinsonian signs and cognitive function in old age. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2005;11:591–597. doi: 10.1017/S1355617705050708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]