Abstract

Background

Sesquiterpene lactones (SL) are plant secondary metabolites that are known for their anti-fungal, anti-bacterial, anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumor properties. Considering that several SL-derived drugs are currently in cancer clinical trials, we have tested two SL molecules, 3-β-methoxy-iso-seco-tanapartholide (β-tan) isolated from Achillea falcata and salograviolide A (Sal A) isolated from Centaurea ainetensis, for their anti-tumor properties. We used the mouse epidermal JB6P + cells as a model for tumor promotion and cellular transformation. Key players that are involved in cellular transformation and tumorigenesis are the AP-1 and NF-κB transcription factors; therefore, we assessed how β-tan and Sal A modulate their signaling pathways in JB6P + cells.

Methods

The effects of β-tan and Sal A on the growth of normal and neoplastic keratinocytes and on the tumor promotion-responsive JB6P + cells were determined using the MTT assay. Anchorage-independent cell growth transformation assays were used to evaluate the anti-tumor promoting properties of these SL molecules in JB6P + cells and dual luciferase reporter assays and western blot analysis were used to investigate their effects on tumor promoter-induced AP-1 and NF-κB activities and protein levels of key AP-1 and NF-кB target genes.

Results

β-tan and Sal A selectively inhibited tumor promoter-induced cell growth and transformation of JB6P + cells at concentrations that do not affect JB6P + and primary keratinocytes basal cell growth. In addition, both molecules reduced basal and tumor promoter-induced NF-κB transcriptional activities, differentially regulated basal and tumor promoter-induced AP-1 transcriptional activities, and modulated key players of the AP-1 and NF-κB signaling pathways.

Conclusions

These results highlight the anti-tumor promoting properties of β-tan and Sal A. These SL molecules isolated from two plant species native to the Middle East may provide opportunities for complementary medicine practices.

Background

There is a renewed interest in the use of natural compounds to prevent/treat several types of diseases including cancer and inflammatory conditions [1,2]. Currently, there are more than 200 natural product-derived drugs already in preclinical/clinical development or in the clinic [1,3,4]. The therapeutic properties of medicinal plants are generally attributed to plant secondary metabolites, an example of which are sesquiterpene lactones (SL), which are present almost exclusively in plant species belonging to the family Asteraceae[5,6]. This family comprises plant species commonly used in ethnomedicine [7], some of which have been reported to specifically treat diseases such as cancer, inflammation, headaches, and infections [6,8]. Sesquiterpene lactones often colorless and with a bitter taste, are a stable form of terpenoids and are divided into four groups: germacranolides, eudesmanolides, guaianolides, and pseudoguaianolides [6]. The bioactivity of a SL molecule has been attributed to several factors including the number of alkylating centers, the lipophilicity of the molecule, and its geometry [9]. Importantly, several SL-derived drugs are currently being tested in cancer clinical trials [9].

Following bioassay guided fractionation, we have isolated, identified, and characterized two SL molecules of the guaianolide group, 3-β-methoxy-iso-seco-tanapartholide (β-tan) and salograviolide A (Sal A), with promising anti-tumor and anti-inflammatory activities [10-14].

β-tan which was purified from Achillea falcata, a species native to Lebanon and the Middle East [15], differentially inhibited the growth of the epidermal human HaCaT cells at non-cytotoxic concentrations to primary epidermal keratinocytes [11]. Sal A, which was isolated from Centaurea ainetensis, also a species native to Lebanon and the Middle East, was found to possess anti-inflammatory [13,14,16] and anti-cancer activities in a mouse colon cancer model and in skin cancer cells at different stages of tumorigenesis [10,12,17].

In this study, we specifically investigated whether these SL molecules target the tumor promotion stage of tumorigenesis and cell transformation using the well-established JB6 mouse epidermal cell system, which includes the promotion-sensitive P + cells [18,19]. In contrast to tumor initiation, tumor promotion is largely reversible, dependent on epigenetic mechanisms, and is a rate-limiting step in multi-stage carcinogenesis, making it an attractive target for anticancer drugs [20,21]. The JB6P + cells can be transformed to malignancy by tumor promoters, and hence, constitute an ideal model to identify anti-tumor promoting and chemopreventive agents and to decipher their mechanism of action [19,22-24].

The anti-tumor promoting activities of β-tan and Sal A and their modulation of AP-1 and NF-κB signaling were investigated using JB6P + cells. AP-1 and NF-κB signaling pathways have been shown to be up regulated and to play key roles in tumor promotion and epidermal tumorigenesis [19,25]. Members of the AP-1 and NF-κB complexes are expressed at high levels in JB6P + cells [19], and AP-1 and NF-κB activities are required for tumor promotion [26,27]. The inhibition of NF-κB and/or AP-1 activities abrogates transformation in JB6 cells in transgenic mice and in human keratinocytes [25,28-30].

Methods

Cells and culture conditions

Primary mouse keratinocytes (PMKs) were freshly prepared from one- to-two day-old neonatal BALB-c mice as described by Yuspa et al.[31]. The SP-1 benign tumor cell lines were produced in SENCAR mice [31]. The neoplastic PAM212 cell line is a differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) that spontaneously transformed in vitro[32]. I7 is a spindle cell line derived from a skin carcinoma formed from PMKs infected with the v-rasHa and c-fos oncogenes and grafted to nude mice [32]. PAM212, SP1, and I7 cell lines were generously provided by Dr. Stuart H. Yuspa (NIH, Bethesda, MD). The JB6P + cell line is a tumor promoter-sensitive clonal variant (clone 41, subclone 5a), derived from the JB6 model for tumor promotion, and originally derived from primary mouse epidermal cells [33]. The JB6P + cell line was generously provided by Dr. Nancy Colburn (NCI, Frederick, MD).

SP1, PAM212, and PMK cells were cultured in fresh Eagle Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) (Bio Whittaker, Cambrex Co., MD) containing 10% chelated fetal bovine serum (FBS) with no more than 0.05 mM Ca++ to maintain a basal proliferating cell phenotype [34], 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomysin antibiotics (Gibco-BRL Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). I7 cells were cultured in complete EMEM medium with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomysin. JB6P + cells were cultured in EMEM (SIGMA, M2279) containing 4% heat inactivated FBS (Gibco BRL Life), 2 mM L-glutamine, 25 μg/mL of gentamicin (SIGMA SG 1397 M10) and 1% non-essential amino acids (NEAA) (Gibco). JB6P + cells were used up to ten passages in culture to avoid spontaneous transformation in vitro. All cells were grown in a humidified incubator which was set at 95% air and 5% CO2 except for PMKs which were grown in 93% air and 7% CO2.

Sesquiterpene lactones isolation and cell treatments

Extraction, purification, and identification of the SL β-tan and Sal A from Achillea falcata and Centaurea ainetensis, respectively, were performed as previously described [11,14]. Briefly, the plant material was soaked in methanol and then subjected to filtration and several fractionation steps where the different fractions were subjected to bio-guided fractionation. The sub-fractions with the most potent anti-proliferative activities were further purified, and the pure bioactive compounds, Sal A from Centaurea ainetensis and β-tan from Achillea falcata were identified using 1 H and 13 C NMR identified using several spectroscopic techniques including 1D and 2D NMR as well as mass spectrometry, UV, and IR. β-tan and Sal A were prepared from a stock of 20 mg/ml diluted in absolute ethanol. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of β-tan and Sal A. For the control conditions, concentrations of ethanol in culture medium did not exceed 0.1% which had no effect on the growth of cells (data not shown).

Cell growth assay

Cell growth was assayed at indicated time points using the MTT Cell Proliferation Kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (Roche Diagnostics). The proliferation assay is an MTT-based method which measures the ability of metabolically active cells to convert tetrazolium salt into a blue formazan product, the absorbance of which is recorded at 595 nm using an ELISA microplate reader. Cell growth results were expressed as percentage of control and were derived from the mean of triplicate wells.

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates, at a density of 1 x 105 cells/ml in 100 μl media, and incubated until confluency reached 50%. After which the media was removed and 100 μl of fresh media containing different concentrations of β-tan or Sal A were placed for treatment conditions, or a maximum of 0.1% ethanol in media for control conditions. For MTT assays using the phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) (Enzo Life Sciences, USA), JB6P + cells were treated with either 5 nM TPA [35] in media only, or with the indicated concentrations of β-tan or Sal A with or without 5 nM TPA co-treatment.

Anchorage-independent growth transformation assay

Colony growth in soft agar is a well-established index of cell transformation [24]. Anchorage-independent growth was studied using the CytoSelectTM 96-Well Cell Transformation Assay kit (Cell Biolabs) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The base agar layer (0.6% agar, 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine and 25 μg/ml gentamicin) was layered into wells of a 96-well plate and allowed to solidify. Once solidified, the cell agar layer containing 0.4% agar with JB6P + cells treated with the indicated concentrations of β-tan and Sal A, with 5 nM TPA [23,35,36], in complete EMEM (10% FBS), was layered on top of the base agar layer. The indicated concentrations of β-tan and Sal A were then prepared in complete EMEM (10% FBS), with 5 nM TPA and placed over the solidified cell agar layer. The cells were incubated for 9 ± 1 day at 37°C and 5% CO2, replenished with the indicated concentrations of β-tan and Sal A with 5 nM TPA every 3 days. Colonies were photographed and then quantified using the CyQuant GR Dye where the fluorescence was measured using a 96-well fluorometer set at a 485/520 nm filter set.

Dual luciferase reporter assay for AP-1 and NF-κB transcriptional activities

JB6P + cells were seeded in 24-well plates (1 x 105 cells/ml), and at 60–80% confluency, cells were co-transfected with the AP-1 (pXP2-35alb-Luc, 0.8 μg) or NF-κB (pGL2-IL-6–Luc, 0.8 μg) firefly luciferase reporter plasmids with the renilla luciferase reporter plasmid (pRL-SV40, 0.04 μg). The pXP2-35alb-Luc harbors the albumin promoter upstream from the luciferase gene. Within this promoter, the GCN4 oligo sequence, which harbors the AP-1 binding site, was ligated. The pGL2-IL-6–Luc uses the IL-6 promoter region containing four putative NF-κB binding sites. These reporter plasmids were kindly provided by Dr. Nancy Colburn (NCI). Co-transfection was done using LipofectamineTM 2000 with PLUSTM reagent (Invitrogen), without antibiotics for 3 h at 37°C, 5% CO2, then replenished with complete EMEM (4% heat-inactivated FBS, with antibiotics) for at least 12 h. Cells were then treated with the indicated concentrations of β-tan and Sal A, with or without 16 nM TPA for 24 h as described [35]. Cell lysates were then prepared and luminescence measured using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (Promega) as per manufacturer’s instructions. The firefly reporter transfection efficiencies were normalized relative to the renilla luciferase activity generated by this vector and plotted as percentage of control.

Western blot analysis

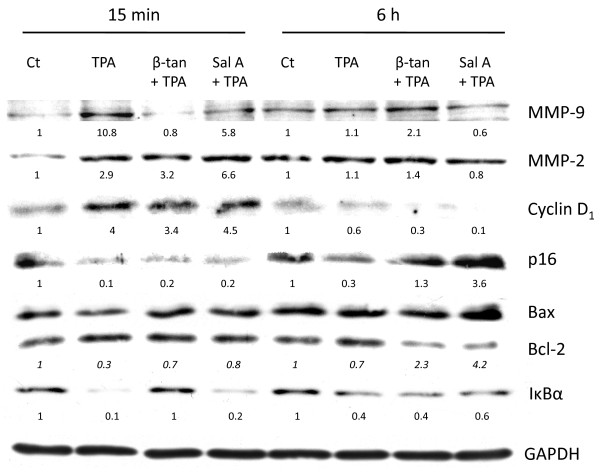

JB6P + cells were plated in 100 mm dishes at a density of 50,000 cells/ml. At 80–90% confluency, cells were starved with 0.1% FBS for 24 h, then were pre-treated with either 10 μg/ml β-tan or 15 μg/ml Sal A for 1 hr followed by 15 min or 6 h 32 nM TPA [35,37]. Whole cell protein extracts (30 μg) were prepared as described [10] and probed overnight at +4 °C with primary antibodies against MMP-9 (Chemicon, Millipore) MMP-2 (Chemicon, Millipore), GAPDH, IκBα, cyclin D1, p16, Bax and Bcl-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) followed by secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. Equal protein loading and quality were verified through GAPDH reprobing and Ponceau staining of membranes. The immunocomplexes were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescent kits obtained from Santa Cruz (ECL system). Bands were quantified using ImageQuant software and the Molecular Dynamics 860 System (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). In some western blots, adjustments of brightness and contrast were applied to all bands of the same membrane image.

Statistical analysis

Data presented are the means ± SE of at least two independent experiments or as indicated. Significant differences were determined using the post-hoc tests; Tukey, SNK and Dunnett tests of the SPSS Version 16.0 software. Significance was set at indicated p-values (0.05, 0.01 or 0.001).

Results

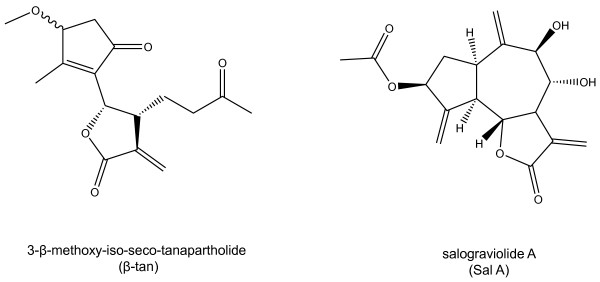

We have previously shown that β-tan and Sal A which belong to the same guaianolide group, exhibit selective anti-tumor activities with minimal effects on normal cells [11,17]. In this study, we investigated whether Sal A and β-tan (Figure 1), attenuate tumor promotion, using the JB6 tumor model. We focused on AP-1 and NF-κB signaling pathways, known to play crucial roles in tumor promotion and in epidermal carcinogenesis [19].

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of 3-β-methoxy-iso-seco-tanapartholide (β-tan) and salograviolide A (Sal A) fromAchillea falcataandCentaurea ainetensis, respectively.

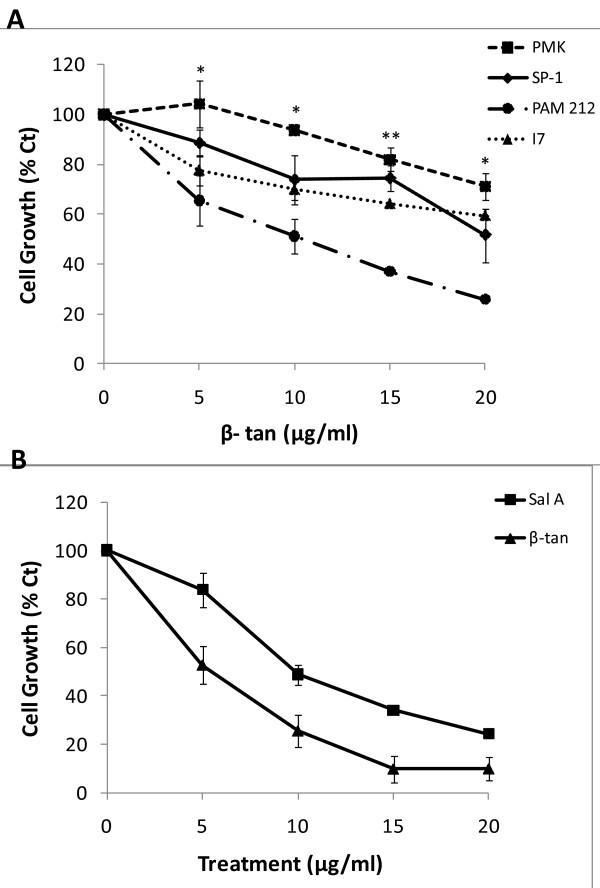

β-tan and Sal A selectively inhibit the growth of tumor cells

We have previously shown, in a murine in vitro model of epidermal carcinogenesis, that Sal A selectively inhibits the cell growth of papilloma and SCC cell lines without significantly affecting the growth of normal cells [10]. Here, we characterized the growth-inhibitory effects of β-tan in vitro using an MTT-based assay. In this model, the primary mouse keratinocytes (PMKs) are representatives of normal cells, the SP-1 cell line as benign tumor cells, PAM-212 cell line as SCC, and the spindle I7 cells as aggressive and metastasizing tumor cells. Treatment with β-tan caused a dose-dependent growth inhibition at 24 h, where a concentration of 10 μg/ml decreased cell growth significantly by 49 ± 7% (p < 0.01) in PAM 212 cells compared to a 6 ± 1% decrease in PMKs cell growth (Figure 2A). The benign SP-1 cells and spindle I7 cells appeared to be less sensitive at this concentration, showing a 26 ± 10% and 30 ± 4% decrease, respectively, that were not significantly different than the normal PMKs (Figure 2A). We have previously performed similar experiments on Sal A and found that 10 μg/ml is selective for tumor cells [10]. In this study, we used this same concentration (10 μg/ml) to study the effect of both β-tan and Sal A on JB6P + cell growth and transformation. β-tan and Sal A produced a dose-dependent growth inhibition in JB6P + cells (Figure 2B). Treatment with 10 μg/ml β-tan and Sal A inhibited JB6P + cell growth by a significant 74 ± 7% and 51 ± 4% (p < 0.01), respectively (Figure 2B). These results show that at low concentrations, both molecules preferentially inhibited the growth of JB6P + cells versus normal keratinocytes, eliminating the possibility that the anti-tumor promoting effects of β-tan and Sal A is due to drug cytotoxicity.

Figure 2.

β-tan and Sal A selectively inhibit the growth of JB6P+ cells. At 50–60% confluency, primary mouse keratinocytes (PMK), SP-1, PAM212, I7 (A) and JB6 P+ (B) cells were treated with the indicated β-tan or Sal A concentrations, or 0.1% ethanol as the control. Cell growth was determined at 24 h and expressed as percentage of control (Ct) treated cells using the MTT Cell Proliferation Kit, as described in Materials and Methods. Significance between neoplastic cell lines and PMKs is indicated by * at p < 0.05 or ** at p < 0.01. Results represent the mean (± SEM) of at least two independent experiments done in triplicate wells.

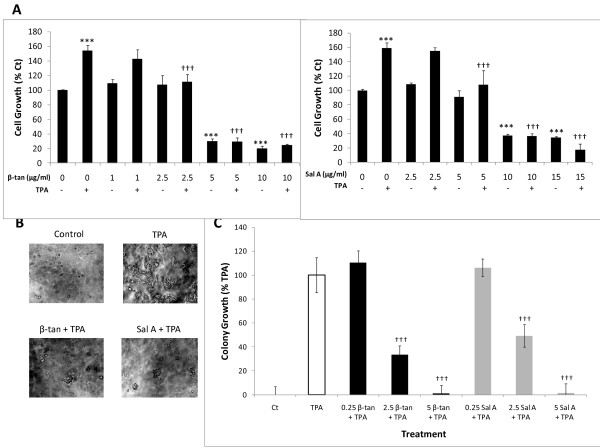

β-tan and Sal A inhibit tumor promoter-induced proliferation and transformation of JB6P + cells

We investigated the anti-tumor promoting properties of β-tan and Sal A in JB6P + cells. Tumor promoters, such as the phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA), increase JB6P + cell growth and transformation. Treatment of JB6P + cells with TPA alone significantly increased their growth at 48 h by approximately 160 ± 7% relative to control (p < 0.001) (Figure 3A). However, co-treatment with β-tan or Sal A with TPA for 48 h inhibited tumor promoter-induced proliferation of JB6P + cells (Figure 3A). β-tan treatment for 48 h at 1 or 2.5 μg/ml did not cause a significant growth inhibition of JB6P + cell proliferation compared to control treated cells (p > 0.05) (Figure 3A). However, co-treatment of 2.5 μg/ml β-tan with TPA showed a significant (p < 0.001) inhibition of TPA-induced proliferation, by 28 ± 10%, relative to the TPA-treated cells; whereas, co-treatment of 1 μg/ml β-tan with TPA showed no significant inhibition on TPA-induced proliferation (p > 0.05) (Figure 3A). β-tan concentrations of 5 and 10 μg/ml had a significant growth inhibitory effect after 48 h on JB6P + cells (by 70 ± 3% and 80 ± 3% respectively) relative to control (p < 0.001), and when co-treated with TPA, cell proliferation was significantly decreased (p < 0.001) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

β-tan and Sal A inhibit promoter-induced proliferation and transformation of JB6P + cells. At 50–60% confluency, JB6P + cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of β-tan and Sal A, with or without TPA co-treatment. (A) Cell growth was determined at 48 h and expressed as percentage of control (Ct) treated cells using the MTT Cell Proliferation Kit. Significance from TPA treatment is indicated by ††† at p < 0.001 while significance from control treatment is indicated by *** at p < 0.001. Results represent the averages (± SEM) of at least two independent experiments done in triplicate wells. (B, C) In the anchorage-independent growth assay, JB6P + cells were suspended in 0.4% soft agar over 0.6% base agar layers, with the indicated β-tan and Sal A concentrations (μg/ml) and TPA co-treatment. Treatments were replenished every three days, where the co-treatment of 2.5 μg/ml β-tan or Sal A with TPA and colony growth was photographed at 200X magnification (B) and quantified at 9 ± 1 day post-seeding using the CytoSelectTM Transformation Assay (C). Colony growth is expressed as percentage of TPA only-treated cells and plotted as mean colony growth (± SEM) of two independent experiments done in triplicate wells (C). Significance from TPA control is indicated by ††† at p < 0.001.

Treatment with Sal A at 5 μg/ml had no growth inhibitory effect in JB6P + cells while this concentration caused a significant inhibition of TPA-induced proliferation by 33 ± 20% relative to the TPA-treated cells (p < 0.001) (Figure 3A). Higher concentrations of Sal A at 10 or 15 μg/ml caused a significant 63 ± 3% and 65 ± 1% decrease in cell proliferation, respectively, with or without the presence of TPA (p < 0.001) (Figure 3A). These results indicate that both SL molecules reduced tumor promoter-induced proliferation of JB6P + cells at concentrations that did not affect the growth of normal cells.

To test whether these two SL molecules inhibit tumor promoter-induced cell transformation, we determined their effects on anchorage-independent cell growth in soft agar, which is a hallmark of malignant transformation. In the presence of tumor promoters, the immortalized but non-tumorigenic JB6P + cells become tumorigenic, forming colonies in an anchorage-independent manner [23]. JB6P + cells treated with only TPA, but not solvent control, exhibit colony growth in soft agar (Figure 3B, C). Importantly, upon co-treatment of β-tan or Sal A with TPA, colony formation was inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner in JB6P + cells (Figure 3B, C). At 0.25 μg/ml, neither β-tan nor Sal A decreased JB6P + colony growth 9 ± 1 day after seeding; however, at 2.5 μg/ml concentrations, which were non-cytotoxic to normal and JB6P + cells by MTT (Figure 2), β-tan and Sal A significantly inhibited tumor promoter-induced colony formation by 66 ± 8% and 51 ± 8%, respectively (p < 0.001) (Figure 3B, C). Both SL molecules completely abrogated colony growth 9 ± 1 day post-seeding at 5 μg/ml concentrations. These results show that β-tan and Sal A inhibit tumor promoter-induced JB6P + cell transformation.

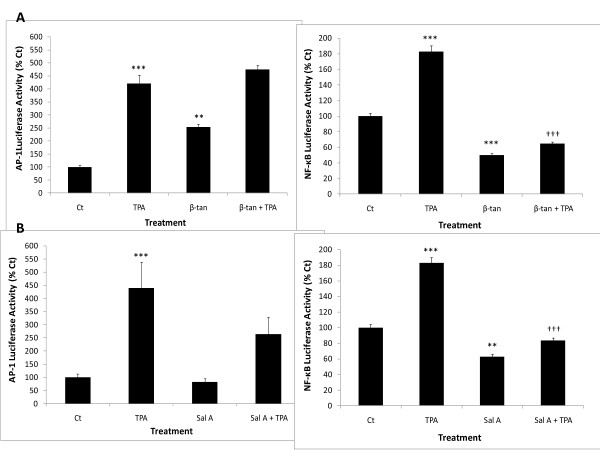

β-tan and Sal A differentially modulate TPA-induced NF-κB and AP-1 activities in JB6P + cells

Elevated levels of AP-1 and NF-κB activities are hallmarks of malignant transformation [19,27,37]. Since β-tan and Sal A both inhibited tumor promoter-induced cell transformation, we hypothesized that these SL molecules mediate their anti-tumor promoting activities by repressing AP-1, NF-κB, or both transcriptional activities.

The application of TPA alone dramatically increased AP-1 and NF-κB luciferase activities in JB6P + cells by four- and approximately two-fold, respectively, compared to control (Figure 4). We tested the effects of β-tan and Sal A on TPA-induced AP-1 and NF-κB transcriptional activities for 24 hours, using 5 μg/ml concentrations as these completely abrogated colony formation with minimal effects on primary keratinocyte cell growth. Unexpectedly, at this concentration, β-tan showed a significant 2.5-fold increase in basal AP-1 activity, relative to control (p < 0.01) and did not decrease TPA-induced AP-1 activity (Figure 4A). Importantly, 5 μg/ml β-tan showed a significant inhibition of basal and TPA-induced NF-κB activity by 50 ± 4% and 64 ± 4%, respectively, at 24 h (p < 0.001) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

β-tan and Sal A decrease basal and TPA-induced NF-κB transcriptional activities. At 60–80% confluency, JB6P + cells were transiently co-transfected with control renilla luciferase reporter construct and AP-1 or NF-κB firefly luciferase reporter constructs and were pre-treated with the indicated concentrations of β-tan (A) or Sal A (B) for 1 h followed by TPA treatment up to 24 h. Results were standardized relative to renilla luciferase and expressed as percentage of control (Ct)-treated cells. Significance from Ct-treated condition is indicated as ** at p < 0.01 and *** at p < 0.001. Significance from TPA-control condition is indicated as †† at p < 0.01 and ††† at p < 0.001. Results are representative of two independent experiments and plotted as averages of triplicate wells (± SD).

Sal A (5 μg/ml) did not modulate basal AP-1 activity, but caused a non-statistically significant decrease in TPA-induced AP-1 activity. Interestingly, Sal A significantly decreased basal and TPA-induced NF-κB transcriptional activities at 24 h by 37 ± 6% and 54 ± 5%, respectively (p < 0.01) (Figure 4B). Our experiments show that both β-tan and Sal A decreased basal and tumor promoter-induced NF-κB activities, which in fact is a characteristic property of SL [6].

β-tan and Sal A modulate key target genes of the AP-1 and NF-κB signaling pathways in JB6P + cells

In JB6 cells, both AP-1 and NF-κB activities are essential for the transformation response, which can be attributed to their roles in the transcriptional activation of genes controlling cellular proliferation, metastasis, angiogenesis, tumor invasion, and apoptosis [38,39]. We next investigated the effect of β-tan and Sal A on the protein levels of key downstream targets of the AP-1 and NF-κB pathways known to be induced by tumor promoters in cell transformation and tumor progression. These target genes are modulated by tumor promoters at early time points; therefore, we pretreated JB6P + cells for one hour with high concentrations of β-tan (10 μg/ml) and Sal A (15 μg/ml), followed by TPA for 15 minutes or 6 hours. We chose these high concentrations that kill approximately 70% of cells by 24 h to be able to detect early protein changes of key AP-1 and NF-κB target genes. Protein levels of metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) were induced by approximately 11-fold in TPA-treated JB6P + cells as early as 15 minutes and were reduced to basal levels and by approximately 50% by pre-treatment with β-tan and Sal A, respectively (Figure 5). On the other hand, MMP-2 protein levels were induced by three-fold in TPA-treated JB6P + cells at 15 minutes but were not reduced by β-tan or Sal A pretreatment. As early as 15 minutes post-TPA treatment, cyclin D1 protein levels were increased by four-fold, and were slightly decreased upon pretreatment with β-tan (Figure 5). The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKI) p16 was reduced by TPA at 15 minutes and 6 hours, and pretreatment with β-tan or Sal A increased p16 protein levels to control or higher levels by 6 hours (Figure 5). Furthermore, we investigated the changes in pro-apoptotic Bax and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins upon treatment with β-tan or Sal A in the presence of TPA. These apoptotic regulators are also key target genes for mediating the AP-1 and NF-κB transformation response. An increase in the ratio of pro-apoptotic over anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins leads to an increase in mitochondrial permeability and subsequent release of cytochrome c, an event central to apoptotic activation [40]. Treatment with TPA alone reduced the pro-apoptotic Bax/Bcl-2 protein ratio to 0.3 folds of control as early as 15 minutes (Figure 5). Pre-treatment with β-tan or Sal A restored the Bax/Bcl-2 protein ratio to almost control values at 15 minutes and to more than two- and four-fold of control values at 6 hours post-TPA treatment (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

β-tan and Sal A modulate the protein levels of key AP-1 and NF-κB downstream target genes in JB6P + cells. JB6P + cells were plated in 100 mm dishes at a density of 50,000 cells/ml. At 80–90% confluency, cells were starved with 0.1% FBS for 24 h, then were pre-treated with either 10 μg/ml β-tan or 15 μg/ml Sal A for 1 h, followed by 15 min or 6 h TPA treatment. Whole cell proteins were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies and reprobed with GAPDH antibody to ensure equal protein loading. Densitometry values were standardized relative to GAPDH for each condition and results are expressed relative to control (Ct) treated cells for each time point. Densitometry values for Bax:Bcl-2 protein ratios are indicated in italics.

Since both SL molecules inhibited TPA-induced NF-κB transactivation, we next studied their effects on the NF-κB inhibitor, IκBα. Treatment with TPA alone abrogated IκBα protein levels as early as 15 minutes (Figure 5). Interestingly, only pre-treatment with β-tan restored IκBα protein levels after 15 minutes of TPA-treatment. These results indicate that pretreatment with β-tan or Sal A regulate TPA-induced AP-1 and NF-кB target genes that are involved in the regulation of cell growth, cell migration, and metastasis.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the anti-tumor promoting effects of β-tan and Sal A, isolated from Achillea falcata and Centaurea ainetensis, respectively, using the JB6 epidermal cell model of tumor promotion and cell transformation. In the multi-stage model of carcinogenesis, the tumor promotion phase is a rate limiting step that is responsible for the clonal expansion of initiated cells and is largely reversible [41], offering a practical approach for identifying potential inhibitors of cancer development [42].

Herein, we report that treatment with either Sal A or β-tan preferentially inhibited the growth of murine neoplastic keratinocytes, whilst sparing normal cells. The promotion-sensitive JB6P + cells were the most sensitive to β-tan treatment at concentrations that did not affect the growth of PMKs. Treatment with Sal A was relatively less potent on JB6P + cells, compared to β-tan, where 10 μg/ml β-tan inhibited cell growth by 74 ± 7%, whereas 10 μg/ml Sal A inhibited by 51 ± 4%. Although both belong to the SL guaianolide family, it seems that β-tan, with its relatively open ring structure, possesses higher flexibility, possibly enhancing β-tan diffusion across the cell membrane; in contrast to Sal A which bears a closed ring structure (Figure 1). In addition to the bioactive –α-methylene-γ-lactone ring present in Sal A and β-tan, the latter harbors an additional alkylating center, the cyclopentenone. Moreover, the presence of two hydroxyl (OH) groups within Sal A renders the molecule less lipophilic, possibly decreasing cell membrane penetration and may explain its reduced toxicity to JB6P + cells compared to β-tan.

In studying the anti-tumor promoting properties of these two purified SL molecules, it was essential to assess their effect on TPA-induced JB6P + cell transformation. In this study, we found that both β-tan and Sal A inhibited TPA-induced JB6P + cell transformation, at concentrations not cytotoxic to normal nor to the non-tumorigenic JB6P + cells. A hallmark of cell transformation is the ability of malignant cells to grow in soft agar in an anchorage-independent manner [18,23,36]. Our results show that β-tan and Sal A, at concentrations that did not inhibit JB6P + cell proliferation, were effective in reducing TPA-induced proliferation and inhibiting TPA-induced colony formation. These results suggest that β-tan and Sal A may have promising chemopreventive properties in epidermal carcinogenesis. Future in vivo experiments are required to confirm the chemopreventive properties of these purified SL molecules. However, a limiting step for in vivo studies will be the availability of large quantities of these molecules.

The activation of the transcription factors AP-1 and NF-κB is essential for tumor promotion and neoplastic transformation, and are highly expressed in the promoter-sensitive JB6P + cells, and the inhibition of both or either one of these signaling pathways is sufficient to inhibit neoplastic transformation [19,23,25]. To study the modulation of tumor promoter-induced AP-1 and NF-κB transcriptional activities by β-tan and Sal A in JB6P + cells, concentrations that inhibited JB6P + cell transformation and did not affect normal cell growth were used. Interestingly, both SL molecules decreased basal and TPA-induced NF-κB activities, but not of TPA-induced AP-1 activity. This suggests that β-tan and Sal A primarily inhibit NF-κB signaling in tumor cells. In fact, it is well established that NF-κB is a vital molecular target for various SL, and some of them, such as parthenolide, artimisinin and thapsigargin are currently in cancer clinical trials [6,9,43]. This can be attributed to the presence of the α-methylene-γ-lactone functional group, which directly alkylates cysteine residues of the p65 subunit, interfering with DNA binding [6,44]. In fact, elevated NF-κB signaling is sufficient to induce epidermal tumor transformation [27]. This prompted us to study the effect of these SL molecules on the protein levels of one of the main NF-κB inhibitors, IκBα. Previous studies have shown that the expression of non-degradable mutants of IκBα and antisense RNA inhibition of NF-κB, result in tumor regression [29,45-47]. Interestingly, only pre-treatment with β-tan restored IκBα protein levels after 15 minutes of TPA-treatment, suggesting that Sal A and β-tan differentially mediate their inhibition of NF-κB signaling. This differential regulation of IκBα proteins by the SL molecules can be attributed to their differences in alkylating centers and lipophilicity, thus, affecting their interaction with the IκBα proteins. Nevertheless, β-tan also significantly increased basal AP-1 levels in JB6P + cells at concentrations that decreased cell growth. This may implicate the dual role of AP-1 in increased cell proliferation and cell death [48].

Since earlier studies have shown that AP-1 and NF-κB can interact together [49], we assessed how both SL molecules modulated key downstream target genes, containing TPA response elements (TREs) common to both AP-1 and NF-κB. Metalloproteinases are essential for tumor promotion, progression, and invasion and AP-1 and NF-κB play a dominant role in the transcriptional activation of the majority of MMPs [50,51] including MMP-9 and MMP-2. In fact, it was shown in mice lacking MMP-9 that this gene is functionally involved in the regulation of oncogene-induced keratinocyte hyperproliferation, progression to invasive cancer, and end-stage malignant grade epithelial carcinomas [52]. Treatment of TPA-promoted JB6P + cells with β-tan or Sal A, abrogated MMP-9, but not MMP-2, protein levels. This implies that the two SL molecules differentially modulate MMP protein levels suggesting the regulation of MMP2 by factors other than AP-1 and NF-κB.

Another important AP-1 and NF-κB target gene is the CDKI p16. Both SL molecules noticeably up regulated p16 that was reduced upon TPA treatment, which suggests that β-tan and Sal A inhibit cell cycle progression that is induced by tumor promoters. Furthermore, AP-1 and NF-κB components also regulate apoptotic proteins such as the pro-apoptotic Bax and the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins [38,51]. SL are known to be inducers of apoptosis in a variety of cancer cells, and this is considered one of the important mechanisms by which SL exert their anti-tumor properties [6]. Our results show that both β-tan and Sal A increase the Bax:Bcl-2 ratios in TPA-promoted JB6P + cells and suggest that Bcl-2 family members are involved in the growth suppressive effects of β-tan and Sal A.

Conclusions

This is the first report which investigates the anti-tumor promoting effects of the SL β-tan and Sal A in cell transformation. Our studies highlight the mechanism by which these SL molecules inhibit tumor promotion by reducing TPA-induced NF-κB activity and in regulating several downstream players involved in cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and tumor invasion. It is well established that tumor promotion is epigenetically regulated, and numerous plant-derived anti-cancer drugs are modulators of epigenetic processes [53], therefore it would be interesting to test whether these purified SL molecules are epigenetic regulators. Finally, future studies investigating the anti-tumor promoting properties in vivo are needed to test the potential chemopreventive use of these SL molecules.

Abbreviations

AP-1, Activator protein-1; β-tan, 3-β-methoxy-iso-seco-tanapartholide; CDKI, Cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor; EGF, Epidermal growth factor; EMEM, Eagle’s minimum essential medium; FBS, Fetal bovine serum; IκBα, Inhibitor of NF-κB; MMP, Matrix metalloproteinase; NF-κB, Nuclear factor-κB; NEAA, Non-essential amino acids; NMR, Nuclear magnetic resonance; PMKs, Primary mouse keratinocytes; Sal A, Salograviolide A; SEM, Standard error of mean; SL, Sesquiterpene lactones; TNFα, Tumor necrosis factor α; TPA, 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate; TREs, TPA response elements.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MS, AG and RH performed the experiments and data analysis. MS wrote the manuscript. AG provided statistical analysis and revised the manuscript. NS supervised the extraction and identification of β-tan and Sal A. SNT contributed in the identification and selection of plant species with potential medicinal properties, provided plant material for isolation and testing of molecules, and contributed to the editing of the manuscript. ND designed and oversaw the study, interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Melody Saikali, Email: ms200@aub.edu.lb.

Akram Ghantous, Email: ayg01@aub.edu.lb.

Racha Halawi, Email: rzh04@aub.edu.lb.

Salma N Talhouk, Email: ntsalma@aub.edu.lb.

Najat A Saliba, Email: ns30@aub.edu.lb.

Nadine Darwiche, Email: nd03@aub.edu.lb.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Middle East Science Fund (MESF, Jordan). We thank Dr. Stuart Yuspa for supplying the SP-1, PAM 212 and I7 cell lines; Dr. Nancy Colburn for supplying the JB6P + cells, AP-1 (pXP2-35alb-Luc) and NF-κB (pGL2-IL-6–Luc) plasmids; Dr. Marwan El Sabban for the MMP-9 and MMP-2 antibodies; Dr. Rihab Nasr and Dr. Hala Mohtaseb for their valuable suggestions; Dr. Fadia Homeidan for her critical review of the manuscript; and Kamal A. Shair Central Research Science Laboratory at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon.

References

- Harvey AL. Natural products in drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today. 2008;13:894–901. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah B, Seth A, Maheshwari K. A review on medicinal plants as a source of anti-inflammatory agents. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2011;5:101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Darwiche N, El-Banna S, Gali-Muhtasib H. Cell cycle modulatory and apoptotic effects of plant-derived anticancer drugs in clinical use or development. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery. 2007;2:361–379. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traditional Medicine Fact Sheet No. 134. 2008. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs134/en/

- Merfort I. Perspectives on sesquiterpene lactones in inflammation and cancer. Current Drug Targets. 2011;12:1560–73. doi: 10.2174/138945011798109437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Won YK, Ong CN, Shen HM. Anti-cancer potential of sesquiterpene lactones: bioactivity and molecular mechanisms. Current Medicinal Chemistry-Anti-Cancer Agents. 2005;5:239–249. doi: 10.2174/1568011053765976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaij-a-Kamb M, Amoros M, Girre L. Search for new antiviral agents of plant origin. Pharmaceutica acta Helvetiae. 1992;67:130–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurib-Fakim A. Medicinal plants: traditions of yesterday and drugs of tomorrow. Molecular aspects of Medicine. 2006;27:1–93. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghantous A, Gali-Muhtasib H, Vuorela H, Saliba NA, Darwiche N. What made sesquiterpene lactones reach cancer clinical trials? Drug Discovery Today. 2010;15:668–678. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghantous A, Tayyoun AA, Lteif GA, Saliba NA, Gali-Muhtasib H, El-Sabban M, Darwiche N. Purified Salograviolide A isolated from Centaurea ainetensis causes growth inhibition and apoptosis in neoplastic epidermal cells. International Journal of Oncology. 2008;32:841–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghantous A, Nasser N, Saab I, Darwiche N, Saliba NA. Structure–activity relationship of seco-tanapartholides isolated from Achillea falcata for inhibition of HaCaT cell growth. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;44:3794–3797. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Najjar N, Dakdouki S, Darwiche N, El-Sabban M, Saliba NA, Gali-Muhtasib H. Anti-colon cancer effects of Salograviolide A isolated from Centaurea ainetensis. Oncology Reports. 2008;19:897–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talhouk RS, El-Jouni1 W, Baalbaki R, Gali-Muhtasib H, Kogan J, Talhouk S. Anti-inflammatory bio-activities in water extract of Centaurea ainetensis. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2008;2:024–033. [Google Scholar]

- Saliba NA, Dakdouki S, Homeidan F, Kogan J, Bouhadir K, Talhouk S, Talhouk R. Bio-guided identification of an anti-inflammatory guaianolide from Centaurea ainetensis. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2009;47:701–707. doi: 10.1080/13880200902933021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nehmé M. Wild flowers of Lebanon. National Council for Scientific Research, Beirut, NCSR Beirut (Lebanon); 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saghir J, Al-Ashi R, Salloum R, Saliba NA, Talhouk RS, Homaidan FR. Anti-inflammatory properties of Salograviolide A purified from Lebanese plant Centaurea ainetensis. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2009;9:36. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-9-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gali-Muhtasib H, Fakhoury I. In: Advances in Cancer Therapy. Gali-Muhtasib H, editor. InTech, 388; 2011. Salograviolide A: A Plant-Derived Sesquiterpene Lactone with Promising Anti-Inflammatory and Anticancer Effects; pp. 369–388. [Google Scholar]

- Colburn NH, Former BF, Nelson KA, Yuspa SH. Tumour promoter induces anchorage independence irreversibly. Nature. 1979;281:589–591. doi: 10.1038/281589a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar A, Young MR, Colburn NH. The role of AP-1, NF-kappaB and ROS/NOS in skin carcinogenesis: the JB6 model is predictive. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2002;234-235:185–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Plass C, Gerhäuser C. Cancer chemoprevention by targeting the epigenome. Current Drug Targets. 2010;12:1925–1956. doi: 10.2174/138945011798184155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YW, Kuo CT, Stoner K, Huang TH, Wang LS. An overview of epigenetics and chemoprevention. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:2129–2136. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colburn NH. Tumor promoter produces anchorage independence in mouse epidermal cells by an induction mechanism. Carcinogenesis. 1980;1:951–954. doi: 10.1093/carcin/1.11.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Birrer MJ, Watts RG, Matrisian LM, Colburn NH. Blocking of tumor promoter-induced AP-1 activity inhibits induced transformation in JB6 mouse epidermal cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1994;91:609–613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber TJ, Siegel RW, Markillie LM, Chrisler WB, Lei XC, Colburn NH. A paracrine signal mediates the cell transformation response to low dose gamma radiation in JB6 cells. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2005;43:31–37. doi: 10.1002/mc.20092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JJ, Westergaard C, Ghosh P, Colburn NH. Inhibitors of both nuclear factor-κB and activator protein-1 activation block the neoplastic transformation response. Cancer Research. 1997;57:3569–3576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young MR, Li JJ, Rincón M, Flavell RA, Sathyanarayana BK, Hunziker R, Colburn NH. Transgenic mice demonstrate AP-1 (activator protein-1) transactivation is required for tumor promotion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1999;96:9827–9832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu TC, Nair R, Tulsian P, Camalier CE, Hegamyer GA, Young MR, Colburn NH. Transformation nonresponsive cells owe their resistance to lack of p65/nuclear factor-κB activation. Cancer Research. 2001;61:4160–4168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts RG, Huang C, Young MR, Li JJ, Dong Z, Pennie WD, Colburn NH. Expression of dominant negative Erk2 inhibits AP-1 transactivation and neoplastic transformation. Oncogene. 1998;17:3493–3498. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu TC, Young MR, Cmarik J, Colburn NH. Activator protein 1 (AP-1)- and nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kappaB)-dependent transcriptional events in carcinogenesis. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2000;28:1338–1348. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young MR, Yang HS, Colburn NH. Promising molecular targets for cancer prevention: AP-1, NF-[kappa] B and Pdcd4. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2003;9:36–41. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4914(02)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuspa SH, Koehler B, Kulesz-Martin M, Hennings H. Clonal growth of mouse epidermal cells in medium with reduced calcium concentration. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1981;76:144–146. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12525490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh DA, Welty DJ, Player A, Yuspa SH. Two oncogenes, v-fos and v-ras, cooperate to convert normal keratinocytes to squamous cell carcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1990;87:643–647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colburn NH, Wendel EJ, Abruzzo G. Dissociation of mitogenesis and late-stage promotion of tumor cell phenotype by phorbol esters: mitogen-resistant variants are sensitive to promotion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1981;78:6912–6916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuspa SH, Kilkenny AE, Steinert PM, Roop DR. Expression of murine epidermal differentiation markers is tightly regulated by restricted extracellular calcium concentrations in vitro. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1989;109:1207–1217. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.3.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzukawa K, Weber TJ, Colburn NH. AP-1, NF-kappa-B, and ERK activation thresholds for promotion of neoplastic transformation in the mouse epidermal JB6 model. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2002;110:865–870. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Cmarik JL, Wendel EJ, Colburn NH. Differential transformation efficiency but not AP-1 induction under anchorage-dependent and-independent conditions. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:1001–1004. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.5.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KW, Kang NJ, Heo YS, Rogozin EA, Pugliese A, Hwang MK, Bowden GT, Bode AM, Lee HJ, Dong Z. Raf and MEK protein kinases are direct molecular targets for the chemopreventive effect of quercetin, a major flavonol in red wine. Cancer Research. 2008;68:946–955. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eferl R, Wagner EF. AP-1: a double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2003;3:859–868. doi: 10.1038/nrc1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl HL. Activators and target genes of Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors. Oncogene. 1999;18:6853–6866. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plati J, Bucur O, Khosravi-Far R. Apoptotic cell signaling in cancer progression and therapy. Integative Biology. 2011;3:279–296. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00144a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennings H, Shores R, Wenk ML, Spangler EF, Tarone R, Yuspa SH. Malignant conversion of mouse skin tumours is increased by tumour initiators and unaffected by tumour promoters. Nature. 1983;304:67–69. doi: 10.1038/304067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding M, Feng R, Wang SY, Bowman L, Lu Y, Qian Y, Castranova V, Jiang BH, Shi X. Cyanidin-3-glucoside, a natural product derived from blackberry, exhibits chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:17359–17368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehner SP, Heinrich M, Bork PM, Vogt M, Ratter F, Lehmann V, Schulze-Osthoff K, Dröge W, Schmitz ML. Sesquiterpene lactones specifically inhibit activation of NF-kappa B by preventing the degradation of I kappa B-alpha and I kappa B-beta. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:1288–1297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Pineres AJ, Castro V, Mora G, Schmidt TJ, Strunck E, Pahl HL, Merfort I. Cysteine 38 in p65/NF-kappaB plays a crucial role in DNA binding inhibition by sesquiterpene lactones. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:39713–39720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101985200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Antwerp DJ, Martin SJ, Kafri T, Green DR, Verma IM. Suppression of TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis by NF-kappaB. Science. 1996;274:787–789. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finco TS, Westwick JK, Norris JL, Beg AA, Der CJ, Baldwin AS. Oncogenic Ha-Ras-induced signaling activates NF-κB transcriptional activity, which is required for cellular transformation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:24113–24116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latimer M, Ernst MK, Dunn LL, Drutskaya M, Rice NR. The N-Terminal Domain of I kappa B alpha Masks the Nuclear Localization Signal (s) of p50 and c-Rel Homodimers. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1998;18:2640–2649. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaulian E, Karin M. AP-1 as a regulator of cell life and death. Nature Cell Biology. 2002;4:E131–E136. doi: 10.1038/ncb0502-e131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein B, Baldwin AS, Ballard DW, Greene WC, Angel P, Herrlich P. Cross-coupling of the NF-kappa B p65 and Fos/Jun transcription factors produces potentiated biological function. The EMBO journal. 1993;12:3879–3891. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel P, Szabowski A, Schorpp-Kistner M. Function and regulation of AP-1 subunits in skin physiology and pathology. Oncogene. 2001;20:2413–2423. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Lin A. NF-kappaB at the crossroads of life and death. Nature Immunology. 2002;3:221–227. doi: 10.1038/ni0302-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens LM, Tinkle CL, Hanahan D, Werb Z. MMP-9 supplied by bone marrow–derived cells contributes to skin carcinogenesis. Cell. 2000;103:481–490. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00139-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider-Stock R, Ghantous A, Bajbouj K, Saikali M, Darwiche N. Epigenetic mechanisms of plant-derived anticancer drugs. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2012;17:129–173. doi: 10.2741/3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]