Abstract

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi uses type IVB pili to facilitate bacterial self-association, but only when the PilV proteins (potential minor pilus proteins) are not synthesized. This pilus-mediated event may be important in typhoid fever pathogenesis. We initially show that S. enterica serovar Paratyphi C strains harbor a pil operon very similar to that of serovar Typhi. An important difference, however, is located in the shufflon which concludes the pil operon. In serovar Typhi, the Rci recombinase acts upon two 19-bp inverted repeats to invert the terminal region of the pilV gene, thereby disrupting PilV synthesis and permitting bacterial self-association. In serovar Paratyphi C, however, the shufflon is essentially inactive because each of the Rci 19-bp substrates has acquired a single base pair insertion. A PilV protein is thus synthesized whenever the pil operon is active, and bacterial self-association therefore does not occur in serovar Paratyphi C. The data thus suggest that serovar Typhi bacterial self-association using type IVB pili may be important in the pathogenesis of epidemic enteric fever.

Type IVB pili encoded by the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi pil operon mediate bacterial self-association, but only when the presumptive minor pilus proteins PilV1 and PilV2 are not expressed (8). This may be achieved in wild-type serovar Typhi by rapid DNA inversion activity of the shufflon (5, 11), composed of the C-terminal part of the pilV gene and the adjacent rci gene, encoding a site-specific recombinase. The Rci protein acts on inverted 19-bp repeats to invert DNA in the C-terminal region of the pilV gene. The inversion activity inhibits the expression of genes inserted between the inverted repeats, and the activity of Rci increases when DNA is supercoiled (2, 3, 8). The data thus suggest that serovar Typhi self-associates under conditions (such as low oxygen tension in the gut) favoring DNA supercoiling. As this type IVB pilus-mediated event cannot be effected by serovars lacking pil, such as S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, we have suggested that the expression of type IVB pili by serovar Typhi might be important in explaining why only serovar Typhi causes epidemics of enteric fever in humans (8). Inactivation of a similar pil operon in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis decreased mouse virulence, with an increase in the 50% lethal dose of 0.7 log (1).

Proof of the proposal that the pili are important in serovar Typhi pathogenesis in humans ideally requires data from human volunteers ingesting serovar Typhi bacteria showing that a serovar Typhi mutant defective in type IVB pilus expression is avirulent. Such tests are ethically difficult, and we therefore sought an alternative approach to address the possible role of type IVB pili in typhoid fever pathogenesis.

The serovar Typhi pil operon is located in Salmonella pathogenicity island 7 (SPI7), which also carries the viaB gene cluster required for the synthesis of the Vi antigen (9). Both the pil operon and the viaB cluster may have entered serovar Typhi on the same conjugative transposon (12). We therefore thought it likely that other Vi antigen-positive Salmonella serovars might contain a pil operon. In particular, some strains of S. enterica serovar Paratyphi C are Vi+. While serovar Paratyphi strains cause occasional episodes of disease (including fever) in humans, serovar Paratyphi is not associated with large-scale persistent epidemics of enteric fever, which are invariably caused by serovar Typhi. We decided to ask whether serovar Paratyphi C might contain a pil operon and, if so, to ascertain if the pil operon differed in arrangement or function from that of serovar Typhi. If a serovar Paratyphi C pil operon were identical in function to that of serovar Typhi, then the enhanced human virulence (relative to serovar Paratyphi C) of serovar Typhi would not be explained by an activity of the pil operon in serovar Typhi. Rather, the molecular basis of enhanced human virulence would reside in other (possibly uncharacterized) genes which differ between the two serovars. If, however, a pil operon of serovar Paratyphi C were incapable of executing a function of the serovar Typhi pil operon, then this would focus attention on the serovar Typhi-specific pil operon function as possibly key to an understanding of typhoid fever pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Reagents were of molecular biology grade. Enzymes active on DNA were obtained from either Invitrogen or Roche and were used as directed by the suppliers. 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) were purchased from Amersham. Bio-Rad was the supplier of polyvinylidene difluoride membrane.

Media.

Luria-Bertani broth (LB) was prepared as described by Miller (7). Solid medium contained 1.5% (wt/vol) agar. Antibiotics were added, when appropriate, to 5 to 15 μg/ml (tetracycline [TET]), 30 μg/ml (chloramphenicol), 50 μg/ml (kanamycin, rifampin, and streptomycin [STR]), or 100 μg/ml (ampicillin).

Bacterial strains.

Serovar Paratyphi strains (Table 1) were obtained from the Salmonella Genetic Stock Center (SGSC) at the University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Serovar Typhi J341 (Ty2 Vi−) (12) is the wild-type strain used in this work. Serovar Typhimurium J357 [leu trpD2 ilv452 metE551 lys metA22 hsdA(r− m+) hsdB(r− m+) hsdL(r− m+) rpsL120 thyA] cured of virulence plasmid pSLT served as a modifying strain prior to transformation of recombinant plasmids to serovars Paratyphi C or Typhi. To make a serovar Paratyphi C strain proficient in transfer of a conjugative plasmid, an Escherichia coli K-12 strain carrying the conjugative plasmid pRU670 (Rts1::Tn1731) (Kmr Tcr) (8) was conjugated with a spontaneous Rifr derivative of a pilS mutant of the serovar Paratyphi C strain SGSC 2712 (ca. 108 bacteria of each strain) on solid medium for 1 h at 30°C, and transconjugants were obtained and purified by subsequent plating on solid medium with TET and rifampin, also at 30°C. As reported (8), transfer of this plasmid in liquid mating does not involve an R64-like type IVB pil operon. For use as recipients in liquid mating tests, spontaneous rpsL (Strr) mutants of serovar Paratyphi C strains were obtained by plating ca. 3 × 109 bacteria on plates with STR (50 μg/ml). Mutants were obtained at a frequency of ca. 10−8. E. coli K-12 DH5α [supE44 ΔlacU169 (φ80 lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1] was the usual host for recombinant plasmids. E. coli JM109 [F′ traD36 lacIq Δ(lacZ)M15 proA+B+/e14−(McrA−) Δ(lac-proAB) thi gyrA96(Nalr) endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) relA1 supE44 recA1] was used as host for pUST160-pUST169. The xylE gene was obtained by PCR from pCM20 (6).

TABLE 1.

Serovar Paratyphi C strains (which either do or do not express the Vi antigen) also carry the type IVB pilus operon originally described (12) from serovar Typhic

| Serovar and straina | Vi antigen statusb | Presence of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pilS | vexDE | vipAB | ||

| Paratyphi A | ||||

| 2281 | Negative | No | No | No |

| 2276 | Negative | No | No | No |

| Paratyphi B | ||||

| 2221 | Negative | No | No | No |

| 2222 | Negative | No | No | No |

| Paratyphi C | ||||

| 2710 | Negative | Yes | Yes | No |

| 2711 | Negative | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2712 | Positive | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2713 | Positive | Yes | Yes | Yes |

The SGSC numbers are used.

Vi antigen expression as historically assessed by slide agglutination with anti-Vi antigen antiserum.

Total DNA was prepared from various serovar Paratyphi strains, and the presence or absence of specific DNA regions was assessed by PCR amplifications and sequencing of PCR products, if obtained. The details are in the text. Serovar Paratyphi C strains carried either or both the vexDE region (that nearer pil) and the vipAB region (pil distal) of the viaB gene cluster. “Yes” indicates (i) that PCR products of appropriate sizes were obtained from the DNAs of various strains and (ii) that DNA sequencing from either end of these products confirmed their authenticity. “No” usually indicates that no PCR products were obtained; in a few instances, inappropriately sized PCR products were detected. Subsequent DNA sequencing invariably showed that these were spurious.

Primers.

To amplify the entire pilS gene, primers 5′-GTTAAGCAATGGATCCAAAAATGAAACAGAGGG-3′ and 5′-CACACATCCCGCGAATTCAGCCGTTGTAGT-3′, which bind to nucleotides (nt) 13329 to 13361 and nt 13949 to 13978 of GenBank accession no. AY249242, respectively, were employed (the primers differ slightly from serovar Paratyphi C sequences in that they have restriction sites used in earlier cloning work). To amplify the entire vipAB gene region (the pil-distal part of the viaB gene cluster), primers 5′-GCCATCGCCATTGATATAAATTGGTTCATC-3′ (part of the vipB gene; nt 3490 to 3519 of GenBank accession no. D14156) and 5′-GGTGGATGTCAATCTGGAAACCACTG-3′ (part of the vipA gene; nt 1693 to 1718 of GenBank accession no. D14156) were used. To amplify the entire vexDE gene region (the pil-proximal part of the viaB gene cluster), primers 5′-GTGTTCAGCAAGCCAAGCAATCGCTAC-3′ (part of the vexD gene; nt 11011 to 11037 of GenBank D14156) and 5′-TCGTAATAAATCACGGCCATTCTTTGC-3′ (part of the vexE gene; nt 12331 to 12357 of GenBank accession no. D14156) were employed.

To amplify pilV genes, three primers were used. Primer prpilV5′ (5′-GAGTGGATACTGGATCCAAAAAACAAAAAC-3′) hybridizes to DNA (nt 15090 to 15119 of GenBank accession no. AY249242) at the beginning of pilV; the primer has a modified pilV sequence, creating a BamHI site used in earlier cloning work. Primers prpilV13′ and prpilV23′ were, respectively, 5′-CAGGGCTTGAATTCATAATCCGGC-3′ and 5′-CCTGCACCCGGCGAATTCAGGCATGT-3′ (both modified from the pilV sequence to include EcoRI sites) and hybridize to DNA potentially invertible by Rci lying beyond the end of the pilV gene. As implied, the primers will act with prpilV5′ to amplify pilV DNA in an orientation-specific manner. The fragment sizes amplified from serovar Typhi are 1,336 or 1,314 bp, respectively. From serovar Paratyphi C strains, fragments of 1,337 or 1,315 bp, respectively, are obtained.

Measurement of XylE activity.

The assay for measurement of XylE activity, using sonicates of stationary-growth-phase cultures of E. coli JM109-based strains, has been described previously (8). Levels of catechol 2,3-dioxygenase were assayed. Catechol was from Aldrich Inc., Milwaukee, Wis. Enzyme units are expressed as picomoles of 2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde produced per minute per microgram of protein.

Analytical methods.

Plasmid preparation, restriction enzyme digestion, and other DNA manipulations followed the methods of Sambrook et al. (10). Development of immunoblots used the Enhanced Chemiluminescence system (Amersham). Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed on 5% (wt/vol) (stacking gel)-15% (wt/vol) (separating gel) polyacrylamide.

Terminology used in describing DNA sequences in the pilV region.

In wild-type serovar Typhi, DNA invertible by Rci lies between two 19-bp inverted repeat sequences, differing by a single base pair, and termed the V1 or V2 sequences (8). In serovar Paratyphi C strains, the inverted repeats are 20 bp long and are termed the PV1 and PV2 sequences. Use of the terms “V1 orientation” or “PV1 orientation” indicates that a promoter external to potentially invertible DNA reads first through the V1 or PV1 sequence, across invertible DNA, and out through the V2 or PV2 sequence, while use of the terms “V2 orientation” or “PV2 orientation” indicates that the locations of the repeat sequences are reversed.

Construction of serovar Paratyphi C pil mutants.

The construction of serovar Typhi pil mutants, by chromosomal recombination of plasmid-borne mutations, has been described elsewhere (8, 11). The pilS and ΔpilV mutations in the serovar Paratyphi C mutants used in this study are identical to those in the serovar Typhi pil mutants (8). The construction of a serovar Typhi pil mutant where the tac promoter and an upstream Cmr cassette are both inserted in a noncoding region between the pilM and pilN genes, and in which the tac promoter drives the transcription of the pilN-pilV genes, has been described previously (12). An identical mutant of serovar Paratyphi C strain SGSC 2712 was constructed.

Preparation of pili.

Two Cmtac strains were grown in shaking (200 rpm) culture for 18 h at 30°C, and the bacterial numbers were adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 with sterile medium. The cultures (250 ml) were centrifuged at 9,200 × g for 10 min, and the supernatants were then centrifuged at 140,000 × g for 1 h. Each pellet was resuspended in 0.2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline, and each contained type IVB pili, with a yield of ca. 10% of that obtained by sonication of concentrated bacteria (12).

Liquid and plate mating tests.

Liquid and plate mating tests were conducted as described previously (8). Briefly, donor strains (pilS mutants of either serovar Typhi or serovar Paratyphi C, carrying conjugative Tcr plasmids and Strs) in the logarithmic growth phase and recipients (various Strr strains) in the stationary growth phase were mixed in a 10:1 ratio of recipients to donors, and liquid matings proceeded for 1.5 h at 30°C. Dilutions of the mating mixtures were plated with TET (selecting for the R-factor) and STR (counterselecting the donors) for colony enumeration. The plate mating technique has been described previously (8).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The serovar Paratyphi C pil operon sequence discussed in this work has been lodged with GenBank under accession no. AY249242.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Serovar Paratyphi C strains carry a pil operon.

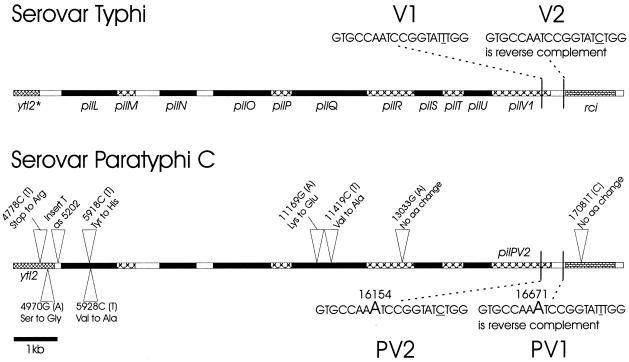

Various serovar Paratyphi strains were examined for the presence of (i) pilS DNA, which encodes the structural pilin of the serovar Typhi type IVB pilus, and (ii) DNA of the viaB gene cluster, which is required for Vi antigen synthesis (Table 1). All four of the serovar Paratyphi C strains examined carried pilS DNA. The two Vi+ strains examined also yielded PCR products from either end of the viaB operon, as expected. One of the Vi-negative strains also yielded both of the viaB-specific products. In this strain, a point mutation inactivating viaB may have occurred during passage or storage. The final Vi-negative strain examined contained DNA from one end, but not the other end, of viaB. This strain has probably suffered a partial deletion of an originally intact viaB operon. Serovar Paratyphi A and B strains carry neither viaB nor pilS DNA. Using primers suggested by the serovar Typhi pil operon sequence (GenBank accession no. AF000001), PCR products were amplified from the genome of serovar Paratyphi C strain SGSC 2712 (CN13/87) and sequenced in both directions. Comparison of the pil operon sequences of serovars Typhi and Paratyphi C (Fig. 1) identified four amino acid residue differences in the pilL-pilV sequence and a single base substitution (in pilR) which does not change the encoded amino acid residue. The between-serovar differences of most interest occurred in the shufflon region. In serovar Typhi, the Rci recombinase encoded by the rci gene (located just downstream of pil) is active to invert DNA between a pair of 19-bp inverted repeats. In serovar Paratyphi C, each of the 19-bp inverted repeat sequences has an extra base (Fig. 1), and they now become 20-bp inverted repeat sequences. In the rci gene (Fig. 1), a single between-serovar base pair difference does not affect the amino acid residue (Pro) encoded. As the between-serovar differences in the shufflon region were of particular interest (see below), PCR products encompassing this region were obtained from the other three (Table 1) pil+ strains of serovar Paratyphi C, and DNA sequencing confirmed that the shufflon sequences of these strains (including the sequences of the 20-bp inverted repeats and the rci genes) were identical to that of serovar Paratyphi C strain SGSC 2712.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the pil operons and adjacent DNA (including the ytl2 gene upstream of pil and the downstream rci gene) of serovar Typhi and serovar Paratyphi C strain SGSC 2712. Serovar Paratyphi C sequence differences with respect to serovar Typhi were confirmed by reamplification and resequencing. In serovar Typhi, two 19-bp inverted repeats, V1 and V2, which differ by a single base (underlined) are used by Rci to invert DNA between the repeats. In serovar Paratyphi C, each repeat has an additional single base pair (shown in a larger typeface) and the shufflon appears locked in the PV2 orientation (see the text). Other differences between the two sequences are discussed in the text. The numbers refer to the serovar Paratyphi C-derived GenBank submission AY249242, where bp 1 is located before the start of a topoisomerase B gene (topB) located upstream of pil. The base pair and amino acid residue differences noted are with reference to serovar Typhi. Thus, “G(A)” and “Ser to Gly” mean that an A in serovar Typhi becomes a G in serovar Paratyphi C and a Ser residue in serovar Typhi becomes a Gly residue in serovar Paratyphi C. Coding regions are shown either filled or hatched; noncoding regions are blank. ytl2*, truncated ytl2 gene.

The shufflon of serovar Paratyphi C is inactive.

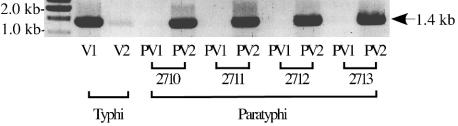

In serovar Typhi, the Rci protein acts to invert DNA located between the 19-bp inverted repeats, and this shufflon activity may be important in typhoid fever pathogenesis (8). DNA supercoiling, required for Rci activity (2, 3), may ultimately regulate shufflon activity, resulting in PilV-free pili when inversion activity is high and PilV-tipped pili when such activity is low. In turn, bacterial self-association is mediated by PilV-free pili and therefore occurs preferentially in the anaerobic environment of the human gut as a prelude to bacterial invasion. PCR was used to amplify DNA characteristic of the two possible shufflon states, from either serovar Typhi or pil+ strains of serovar Paratyphi C (Fig. 2). As previously reported, both possible pilV products were obtained from serovar Typhi DNA, in which the V1 orientation predominates. With the serovar Paratyphi C strains, however, no PCR product was detected from the PV1 orientation, and the shufflons appear to be locked exclusively in the PV2 orientation (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

The shufflons of serovar Paratyphi C strains appear locked in the PV2 orientation. Orientation-specific PCR primers were used to amplify shufflon DNA from either serovar Typhi or from the four pil+ strains of serovar Paratyphi C examined in this work, and the PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. While the serovar Typhi shufflon is predominantly in the V1 orientation (a weak band from the V2 shufflon orientation may be seen in the third track), the shufflons of serovar Paratyphi C strains appear locked in the PV2 orientation, as PCR products characteristic of the PV1 orientation cannot be detected. The first track contains molecular mass markers. The SGSC strain numbers of the serovar Paratyphi C strains used are shown. The approximate size of the PCR products is indicated on the right.

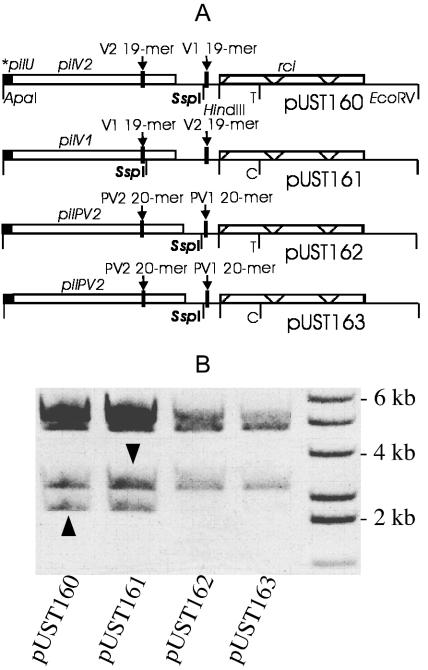

It seemed possible that Rci was unable to act on the 20-bp inverted repeats. To test this suggestion, plasmid pUST162 (Fig. 3A) was constructed to contain the shufflon of serovar Paratyphi C, while plasmid pUST163 was identical to plasmid pUST162 except that the rci gene had the serovar Typhi rci sequence, thus differing in 1 bp from that of the serovar Paratyphi C rci gene. As controls, plasmid pUST161 contained the serovar Typhi shufflon, while plasmid pUST160 was identical to plasmid pUST161 except that the rci gene sequence was that of serovar Paratyphi C. The shufflon of plasmid pUST160 is shown in the orientation opposite to that of the pUST161 shufflon in Fig. 3A, reflecting the cloning strategy. Note, however, that Rci, acting on invertible sequences, establishes equilibrium populations of plasmids carrying such sequences. Shufflon cloning directions are therefore immaterial in such plasmids.

FIG. 3.

The serovar Paratyphi C shufflon is inactive. (A) The shufflons of serovars Typhi (pUST161) and serovar Paratyphi C (pUST162) were cloned into pBluescript SK(+), and two hybrid plasmids (pUST160 and pUST163), with the potentially invertible sequence of either serovar in combination with the rci allele of the other serovar, were also constructed. The HindIII site (shown in pUST160) is artificial and was introduced during PCR-based assembly of plasmid subfragments. The SspI site highlighted in pUST160 is asymmetrically located in potentially invertible DNA, and use of this enzyme therefore yields orientation-specific shufflon fragments. (B) The plasmids in panel A were purified from E. coli JM109 and digested with SspI, and the fragments were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. The lower-molecular-weight fragments resulting from DNA inversion by Rci are indicated by arrowheads. The rci alleles of either pUST160 or pUST161 act to invert DNA between 19-bp inverted repeats, while the 20-bp inverted repeats of either pUST162 or pUST163 are poor Rci substrates. A lane containing molecular mass markers (some annotated) is shown. The rci alleles of serovars Typhi and Paratyphi C are distinguished (as shown) by the presence of a C in serovar Typhi whereas a T occurs in serovar Paratyphi C. *pilU, truncated pilU gene.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of SspI-digested DNA of plasmids pUST160-pUST163 showed that Rci encoded by the rci alleles of either serovar Typhi or Paratyphi C was active to invert DNA between the serovar Typhi-specific 19-bp inverted repeats but apparently failed to act on the serovar Paratyphi C-specific 20-bp inverted repeats (Fig. 3B). The smallest gel fragments of SspI-digested pUST160 and pUST161 are characteristic of the V1 orientation, and at most a trace of such DNA may be noted in the digests of pUST162 and pUST163.

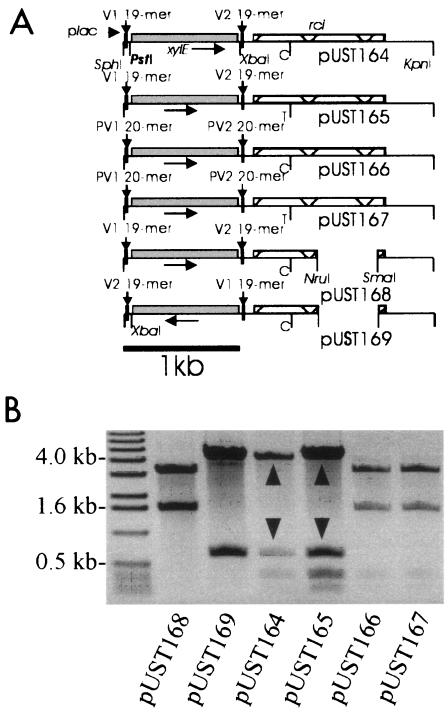

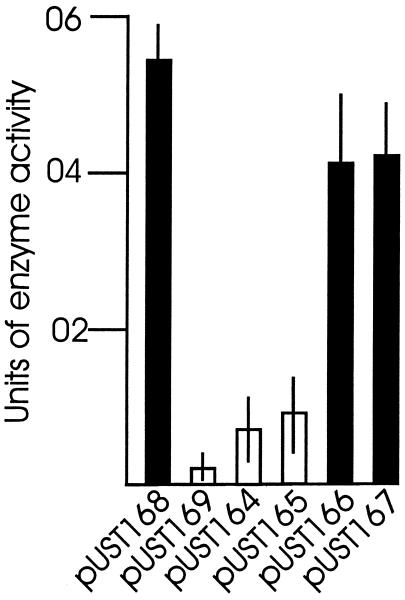

Plasmids pUST164 to pUST167 (Fig. 4A), all of which have a lac promoter reading into cloned DNA from the left, were constructed to contain an xylE gene (without a transcription terminator) bracketed by (i) serovar Typhi-specific 19-bp V1 or V2 inverted repeat sequences or (ii) serovar Paratyphi C-specific 20-bp PV1 or PV2 inverted repeat sequences, followed by either the serovar Typhi or serovar Paratyphi C-specific rci alleles. Plasmids pUST168 and pUST169, in both of which the rci gene has been inactivated by deletion, served as positive and negative controls, respectively. In plasmid pUST168, the xylE gene is locked in the orientation permitting transcription from the lac promoter, while the xylE gene is in the reverse orientation in plasmid pUST169. The rationale was that transcription, from the induced lac promoter, of the xylE gene in the orientation shown in plasmids pUST164 to pUST167 (Fig. 4A) would allow through-transcription of rci, as the intergenic space is only 143 bp and the xylE gene is not followed by a transcription terminator sequence. Under such conditions, Rci expression would be high and DNA between invertible repeat sequences (the xylE gene) would be readily inverted. As the xylE gene would then be in an orientation nonpermissive for transcription, the through-transcription of rci would cease and Rci levels would drop. There would thus be little tendency for the invertible DNA to return to the orientation characteristic of xylE transcription. In summary, growth of E. coli JM109 strains hosting any of plasmids pUST164 to pUST167 in IPTG-containing medium should result in high-level inversion of xylE-containing DNA from the orientations shown in Fig. 4A if the inverted repeats bracketing the xylE DNA are substrates for Rci action. When the xylE gene was bracketed by V1 or V2 19-bp inverted repeats, such inversion was indeed observed (Fig. 4B). When the xylE gene was bracketed by PV1 or PV2 20-bp inverted repeats, however, no trace of inverted DNA was found. The XylE enzyme levels expressed in IPTG-induced E. coli JM109 cultures hosting individual plasmids of the pUST164 to pUST169 series were measured (Fig. 5). When the xylE gene was bracketed by V1 or V2 19-bp inverted repeats, low XylE levels (not significantly different from that of the negative control) were noted. When the xylE gene was bracketed by PV1 or PV2 20-bp inverted repeats, however, XylE levels did not differ significantly from that of the positive control.

FIG. 4.

The serovar Paratyphi C-specific 20-bp inverted repeat sequences are poor Rci substrates. (A) Plasmids were constructed in pUC19 with (i) a promoterless xylE gene behind the lac promoter and between DNA sequences potentially invertible by Rci and (ii) the rci allele of either serovar Typhi or Paratyphi C. The XbaI site (shown in pUST164) is artificial and was introduced during PCR-based assembly of plasmid subfragments. The PstI site highlighted in pUST164 is asymmetrically located in potentially invertible DNA, and use of this enzyme therefore yields orientation-specific shufflon fragments. Plasmids pUST168 and pUST169 (with partially deleted rci genes) are positive and negative controls for XylE expression, respectively. (B) The plasmids in panel A were purified from E. coli JM109 strains grown with IPTG and digested with PstI, and the fragments were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Fragments resulting from DNA inversion by Rci are indicated by arrowheads. The rci alleles of either pUST164 or pUST165 act to invert DNA between 19-bp inverted repeats, while the 20-bp inverted repeats of either pUST166 or pUST167 are poor Rci substrates. Digests of rci-lacking control plasmids (pUST168 and pUST169) are also shown. A lane containing molecular mass markers (some annotated) is shown. The rci alleles of serovars Typhi and Paratyphi C are distinguished (as shown) by the presence of a C in serovar Typhi where a T occurs in serovar Paratyphi C.

FIG. 5.

DNA inversion mediated by Rci separates the xylE gene from the lac promoter. The xylE gene was placed between a pair of 19-bp inverted repeats (in pUST164 and pUST165) or a pair of 20-bp inverted repeats (in pUST166 and pUST167), in an orientation permissive for xylE transcription from the lac promoter (Fig. 4). Strains of E. coli JM109 hosting various plasmids were grown with ampicillin and IPTG, and XylE enzyme levels were assayed. Plasmids pUST168 and pUST169 (Fig. 4) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The XylE enzyme levels from E. coli JM109/pUST164 and E. coli JM109/pUST165 were not significantly different from that of the negative control (open bars). The XylE enzyme levels from E. coli JM109/pUST166 and E. coli JM109/pUST167 were not significantly different from that of the positive control (filled bars). The tests were performed five times, each time in triplicate. Averages and standard errors (error bars) are shown.

Taken together, the data strongly suggest that DNA bracketed by a pair of PV1 and PV2 inverted repeats is poorly invertible by Rci. We suggest that Rci cannot use the serovar Paratyphi C 20-bp inverted repeats as substrates for inversion activity and that the serovar Paratyphi C shufflon is therefore locked in the PV2 position (Fig. 1 and 2). Serovar Paratyphi C strains carrying the type IVB pil operon thus synthesize a PilV protein whenever the pil operon is active.

Serovar Paratyphi C expresses pili, but the pili are not used for bacterial self-association.

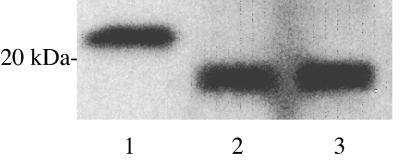

As serovar Paratyphi C strain SGSC 2712 carries a pilS gene, it was of interest to first ask if this strain expressed exported PilS protein, which would in turn suggest an ability of the strain to assemble type IVB pili on the bacterial surface. Transcription of the serovar Paratyphi C pil operon downstream of the pilN gene was augmented by insertion of a tac promoter in the pilM-pilN intergenic space (12), and the serovar Paratyphi C strain SGSC 2712 derivative modified in this manner produced PilS protein at a level similar to that expressed by an equivalently modified strain of serovar Typhi (Fig. 6). The PilS protein is synthesized in a precursor (prePilS) form, bearing a signal sequence that is removed when the protein is exported (12). Expression by serovar Paratyphi C strain SGSC 2712 of the PilS protein, whose molecular weight is lower than that of the prePilS protein, therefore indicates that the prePilS protein is exported, with concomitant cleavage to PilS protein and (presumably) polymerization into pili.

FIG. 6.

Serovar Paratyphi C strain SGSC 2712 synthesizes type IVB pili. The tac promoter was inserted in the pilM-pilN intergenic gap in strains of both serovar Typhi and serovar Paratyphi C, and pili prepared from both strains were solubilized for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and viewed by immunoblotting. Lanes: 1, purified prePilS (100 ng); 2, PilS from serovar Typhi (2 × 108 bacteria); 3, PilS from serovar Paratyphi C SGSC 2712 (2 × 108 bacteria). The prePilS protein is of higher molecular weight than the PilS protein because of signal sequence cleavage, indicative of PilS export, in the bacterial samples. The position of a molecular mass marker is shown on the left.

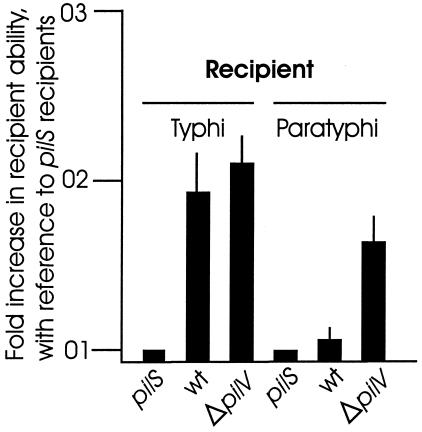

In serovar Typhi, the type IVB pili mediate bacterial self-association, but only when the PilV1 and PilV2 proteins are not made (8). As inactivation of the shufflon in serovar Paratyphi C results in synthesis of a PilV protein whenever the pil operon is active, it was thought possible that a wild-type serovar Paratyphi C strain might be incapable of self-association, while a ΔpilV mutant (which should express PilV-free pili) would show clumping behavior. As described previously (8), a liquid mating assay, in which potentially self-associating bacterial recipients are in 10-fold excess to donors, provides a measure of bacterial self-association, as the recipients tend to enmesh donor bacteria in a developing pellet. This entrapment of donors is reflected in higher transfer of a conjugative plasmid, from donor to recipient, than is the case when the recipient strains do not self-associate. Below, pilS donors of both serovars Typhi and Paratyphi C are used, as these strains do not make pili and therefore cannot contribute to any pilus-mediated bacterial association.

When a pilS donor of serovar Typhi was used in a liquid mating assay with various serovar Typhi strains (Fig. 7), the wild-type and ΔpilV mutant of serovar Typhi showed evidence of bacterial self-association, as previously described (8). When a pilS donor of serovar Paratyphi C was used in a liquid mating assay with various serovar Paratyphi C recipients (Fig. 7), however, only the ΔpilV mutant of serovar Paratyphi C self-associated. The wild-type strain, in which pili may always be capped with a PilV protein, did not self-associate. It should be noted that pil+ strains illustrated in Fig. 7 produce pili from natural promoter(s). Unlike the strains illustrated in Fig. 6, the tac promoter is not used to drive any pil genes in the strains of Fig. 7.

FIG. 7.

The type IVB pili of serovar Paratyphi C strain SGSC 2712 do not mediate bacterial self-association. A liquid mating assay was used to measure bacterial self-association, on the basis that self-associating recipients tend to enmesh donor bacteria in a developing bacterial pellet. The donors were pilS mutants of either serovar Typhi (for the serovar Typhi matings) or serovar Paratyphi C strain SGSC 2712 (for the serovar Paratyphi C matings). Transfer of a conjugative plasmid was measured. The type IVB pili of serovar Typhi mediate bacterial self-association in both the wild-type and ΔpilV mutant strain, while the type IVB pili of serovar Paratyphi C are always capped with a PilV protein and the wild-type strain therefore does not use the pili for self-association. Inactivation of the pilV gene allows serovar Paratyphi C self-association. The experiments were repeated five times, each time in triplicate, and averages with standard errors (error bars) are shown. The pilS to pilS transfer frequencies in individual tests ranged from 3 × 10−3 to 11 × 10−3/donor bacterium, as before (8). Plate mating tests showed that all six plasmid transfers described above were high and uniform.

Bacterial self-association may be important in typhoid fever pathogenesis.

Strains of serovar Paratyphi C carry a pil operon very similar to that of serovar Typhi, but Rci-mediated shufflon activity is essentially absent due to the insertion (relative to serovar Typhi) of a single base pair in each of the 19-bp inverted repeats which (in serovar Typhi) are used by Rci to mediate DNA inversion. The DNA regions with the resulting 20-bp inverted repeats are poor Rci substrates. The shufflon in the chromosome of serovar Paratyphi C appears locked in the PV2 position. A PilV protein will thus be synthesized whenever the pil operon is active, and the pili will thus carry this PilV protein, as a minor component, at all times. The type IVB pili of serovar Paratyphi C therefore cannot mediate bacterial self-association (which requires PilV-free pili). However, serovar Paratyphi C synthesizes and exports (after cleavage of the signal sequence) a PilS protein identical to that of serovar Typhi (Fig. 6). This protein is presumably polymerized into pili.

Proof of the idea that the type IVB pili of serovar Typhi are important in typhoid fever pathogenesis can best come from tests involving the administration of defined pil mutants of serovar Typhi to human volunteers. In the absence of such data, attempts to correlate reduced human virulence with compromised pil functions in Salmonella serovars other than serovar Typhi may be considered useful, even though such serovars are not, of course, isogenic with serovar Typhi at loci other than pil. Serovars Typhi and Paratyphi C differ in the Kauffman-White scheme (4), and the I-CeuI map of serovar Paratyphi C strain RKS4594 is distinct from that of serovar Typhi Ty2. The serovar Paratyphi strain RKS4594 genome map shows potential insertions and deletions with respect to the map of serovar Typhi Ty2 (S.-L. Liu, D. N. Qi, G. R. Liu, W. Q. Liu, Sanderson, K. E., and R. N. Johnston, Abstr. 102nd Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2002, abstr. R-5, p. 459, 2002).

The pil operon of serovar Paratyphi C does not function to effect the bacterial self-association mediated by the homologous operon of serovar Typhi. Also, the shufflon of the pil operon expressed by Vi-positive strains of S. enterica serovar Dublin appears biased in the V2 orientation in the bacterial chromosome (our unpublished data; also see GenBank accession no. AF247502). No other Salmonella serovars express the Vi antigen. This focuses attention on possible within-gut self-association mediated by the serovar Typhi pil operon as potentially important in an understanding of typhoid fever pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Hong Kong Government Research Grants Council.

Editor: V. J. DiRita

REFERENCES

- 1.Collyn, F., M.-A. Léty, S. Nair, V. Escuyer, A. Ben Younes, M. Simonet, and M. Marceau. 2002. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis harbors a type IV pilus gene cluster that contributes to pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 70:6196-6205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gyohda, A., and T. Komano. 2000. Purification and characterization of the R64 shufflon-specific recombinase. J. Bacteriol. 182:2787-2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gyohda, A., N. Furuya, N. Kogure, and T. Komano. 2002. Sequence-specific and non-specific binding of the Rci protein to the asymmetric recombination sites of the R64 shufflon. J. Mol. Biol. 318:975-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kauffman, F. 1961. Die Bakteriologie der Salmonella Species. Munksgaard, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 5.Komano, T., S.-R. Kim, T. Yoshida, and T. Nisioka. 1994. DNA rearrangement of the shufflon determines recipient specificity in liquid mating of IncI1 plasmid R64. J. Mol. Biol. 243:6-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marx, C. J., and M. E. Lidstrom. 2001. Development of improved versatile broad-host-range vectors for use in methylotrophs and other Gram-negative bacteria. Microbiology 147:2065-2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 8.Morris, C., I. S. M. Tsui, C. M. C. Yip, D. K.-H. Wong, and J. Hackett. 2003. The shufflon of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi regulates type IVB pilus-mediated bacterial self-association. Infect. Immun. 71:1141-1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkhill, J., G. Dougan, K. D. James, N. R. Thomson, D. Pickard, J. Wain, C. Churcher, K. L. Mungall, S. D. Bentley, M. T. Holden, M. Sebaihia, S. Baker, D. Basham, K. Brooks, T. Chillingworth, P. Connerton, A. Cronin, P. Davis, R. M. Davies, L. Dowd, N. White, J. Farrar, T. Feltwell, N. Hamlin, A. Haque, T. T. Hien, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, A. Krogh, T. S. Larsen, S. Leather, S. Moule, P. O'Gaora, C. Parry, M. Quail, K. Rutherford, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, K. Stevens, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a multiple drug resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi CT18. Nature (London) 413:848-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 11.Zhang, X.-L., C. Morris, and J. Hackett. 1997. Molecular cloning, nucleotide sequence, and function of a site-specific recombinase encoded in the major “pathogenicity island” of Salmonella typhi. Gene 202:139-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang, X.-L., I. S. M. Tsui, C. M. C. Yip, A. W. Y. Fung, D. K.-H. Wong, X. Dai, Y. Yang, J. Hackett, and C. Morris. 2000. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi uses type IVB pili to enter human intestinal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 68:3067-3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]