Abstract

Through recognition of HLA class I, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) modulate NK cell functions in human immunity and reproduction. Although a minority of HLA-A and –B allotypes are KIR ligands, HLA-C allotypes dominate this regulation, because they all carry either the C1 epitope recognized by KIR2DL2/3 or the C2 epitope recognized by KIR2DL1. The C1 epitope and C1-specific KIR evolved first, followed several million years later by the C2 epitope and C2-specific KIR. Strong, varying selection pressure on NK cell functions drove the diversification and divergence of hominid KIR, with six positions in the HLA class I binding site of KIR being targets for positive selection. Introducing each naturally occurring residue at these positions into KIR2DL1 and KIR2DL3, produced 38 point mutants that were tested for binding to 95 HLA- A, -B and –C allotypes. Modulating specificity for HLA-C is position 44, whereas positions 71 and 131 control cross reactivity with HLA-A*11:02. Dominating avidity modulation is position 70, with lesser contributions from positions 68 and 182. KIR2DL3 has lower avidity and broader specificity than KIR2DL1. Mutation can increase the avidity and change the specificity of KIR2DL3, whereas KIR2DL1 specificity was resistant to mutation and its avidity could only be lowered. The contrasting inflexibility of KIR2DL1 and adaptability of KIR2DL3 fits with C2-specific KIR having evolved from C1-specific KIR, and not vice versa. Substitutions restricted to activating KIR all reduced the avidity of KIR2DL1 and KIR2DL3, further evidence that activating KIR function often becomes subject to selective attenuation.

Keywords: Natural Killer Cells, MHC, Epitopes, Comparative Immunology/Evolution

Introduction

MHC class I molecules function as ligands for a variety of activating and inhibitory receptors expressed by NK cells and CD8 T cells (1-4). In the human MHC, the HLA complex, six genes encode MHC class I molecules: HLA-A, -B, -C, -E, -F and -G, all of which are known to interact with NK cell receptors. Of these HLA-E is the oldest and most conserved; it binds a restricted set of peptides that are largely derived from the leader sequences of other HLA class I molecules and is the ligand for conserved CD94:NKG2 lectin-like receptors (5, 6).

In contrast, HLA-A, -B, -C, and -G bind diverse peptides and furnish ligands for diverse and polymorphic killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR). This family of variable NK cell receptors is of very recent origin, being restricted to the simian primates: monkeys, apes, and humans (7, 8). HLA-G, the ligand for KIR2DL4, is expressed only by extravillous trophoblast (EVT) and is implicated in the interactions between EVT and uterine NK cells (uNK), which are critical for placentation and successful reproduction (9-11). HLA-A, -B and -C are highly polymorphic and function as ligands for both KIR and the αβ TCR of CD8 T cells. Of these three, HLA-C is the most recently evolved and the only one for which all the variant forms (allotypes) are ligands for KIR (12-14). Dimorphism at position 80 in HLA-C defines two epitopes, C1 (asparagine 80) and C2 (lysine 80), that are ligands for different forms of KIR (15). In contrast, only around one third of the HLA-A and HLA-B allotypes have the capacity to interact with KIR (8). Such comparisons indicate that HLA-C, which arose from an HLA-B-like ancestor (16), diverged under selection to become a specialized and dominant source of ligands for KIR. That HLA-C but not HLA-A or –B is expressed by EVT, and uterine NK cells selectively express KIR that recognize HLA-C, further argues that selection pressure from reproduction contributed to the evolution of HLA-C (17, 18).

The C2 epitope, carried by the subset of HLA-C allotypes having lysine 80, is recognized by the inhibitory receptor KIR2DL1 and the activating receptor KIR2DS1. The signaling domains of these two receptors are divergent, but their Ig-like domains, which form the ligand-binding site, have high sequence similarity. The C1 epitope, carried by the subset of HLA-C allotypes having asparagine 80, and two unusual HLA-B allotypes (HLA-B*46:01 and HLA-B*73:01), is recognized by the inhibitory receptor KIR2DL2/3 (19-21). Corresponding to the dimorphism at position 80 in HLA-C is a dimorphism at position 44 in the D1 domain of the KIR that determines the receptors’ specificities. Thus, C2-specific KIR2DL1 and KIR2DS1 have methionine 44, whereas C1-specific KIR2DL2/3 has lysine 44. That mutation at this position was demonstrated to be sufficient to swap the receptors’ specificities led to position 44 being described as the specificity-determining residue (22, 23). Functional studies and clinical correlations point to the C1 and C2 epitopes of HLA-C being the dominant ligands for KIR (24-26). And because C1 and C2 are alternatives, all human individuals have at least one of these epitopes and some have both of them; which is not the case for the A*03/11 epitope of HLA-A recognized by KIR3DL2 (27, 28), or the Bw4 epitope of HLA-A and –B recognized by KIR3DL1 (29, 30). The KIR that recognize epitopes of HLA-A and B form a phylogenetic lineage (lineage II KIR) that is distinguished from the lineage III KIR to which the HLA-C receptors belong (31).

Comparison of primate species shows how KIR co-evolve with their cognate MHC class I ligands. Old World monkeys have MHC class I genes resembling HLA-A and -B, but no equivalent to HLA-C. Correspondingly, in these species there are multiple lineage II KIR genes but only one lineage III KIR (32-37). An equivalent to HLA-C is present only in the hominids (great apes and humans) and exists in a more primitive state in the orangutan MHC where the gene is not fixed, as it is in human and chimpanzee MHCs, and all the allotypic variants carry the C1 epitope (12, 38). Nonetheless, there are multiple lineage III KIR in the orangutan, but only one lineage II KIR, indicating the functional impact of the emergence of MHC-C and its cognate lineage III KIR.

By the time of the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees, the C2 epitope and its interaction with lineage III KIR had evolved from the C1 epitope and its cognate receptors. The chimpanzee maintains a diverse array of nine lineage III KIR that recognize the C1 and C2 epitopes with good avidity, which includes both inhibitory and activating KIR (7). In contrast, of the seven human lineage III KIR only four bind to HLA-C and the other three have no demonstrable binding to any HLA class I (39, 40). These comparisons show how the selection pressures acting upon the interactions of lineage III KIR with human HLA-C, and its MHC-C counterparts in other species, have been remarkably variable throughout hominid evolution.

To investigate the effects of natural selection on hominid lineage III KIR, we identified sites of positive diversifying selection within the ligand-binding site and assessed the functional effects of this variation by mutagenesis directed at these sites in human C2–specific KIR2DL1 and C1-specific KIR2DL2/3. For KIR2DL1 the 2DL1*003 allele was chosen as the target for mutagenesis, because it is the most common allele in many human populations. KIR2DL2/3 has two distinctive allelic lineages: KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3. We chose 2DL3*001, the most frequent KIR2DL3 allele, as the target for mutagenesis because KIR2DL2 is a recombinant form (with greater sequence similarity to KIR2DL3 in the Ig-like domains and to KIR2DL1 in the stem, trans-membrane and cytoplasmic regions) that in functional assays recognizes both C1 and C2, whereas KIR2DL3 appears functionally specific for C1, although exhibiting some cross-reactivity with C2-bearing allotypes in direct-binding assays (21). The disadvantage to choosing KIR2DL3 over KIR2DL2 is availability of a crystallographic structure only for KIR2DL2 bound to HLA-C (41), but not for KIR2DL3 bound to HLA-C.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

The human cell line NKL was maintained as described (42). The G4-NKL cell line was derived from NKL by specific siRNA knockdown of LILRB1 expression using the pSIREN-RetroQ vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) (43). Transduction of NKL and G4-NKL with wild-type and mutant KIR was performed as described (13) with minor modifications. The full-length KIR coding region was cloned into the pIB2 expression vector (kindly provided by Dr Mark Davis, Stanford University, CA), and transduced into Phi-NX cells (kindly provided by Dr Garry Nolan, Stanford University, CA) to generate recombinant amphotrophic retrovirus, which was then used to infect NKL cells. After two weeks of infection, the NKL cells were FACS-purified using KIR-specific monoclonal antibodies. After such selection >95% of the cells expressed KIR. Transduced cells were periodically checked for surface expression of KIR using specific monoclonal antibodies.

Transduced NKL cells express GFP driven by an IRES from the same promoter as the KIR. This allowed cells transduced with different KIR to be sorted by FACS for equivalent GFP expression. Subsequently the sorted transductants were analyzed for KIR expression using several KIR-specific monoclonal antibodies that interact with lineage III KIR (EB-6, CH-L, anti-2DS4 and NKVFS1) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Among these the reactivity of NKVFS1, which has a very broad reactivity for lineage III KIR from all hominid species, was particularly constant and allowed us to select cells with similar levels of KIR expression for use in functional assays (13, 21, 39, 40).

The HLA-A, B and C deficient cell-line 721.221 (subsequently referred to as 221 cells) was transfected with individual HLA class I alleles which had been mutated in the leader peptide so that on binding to HLA-E the derived peptides do not permit interaction with CD94:NKG2A (44). Lacking transporter-associated proteins, the T2 human cell line has a reduced amount of HLA-A*02 to the cell surface and no detectable amount of the other endogenous HLA class I allotypes (45). Permanent transduction of T2 with HLA-A*11:02 was achieved using the Amaxa Nucleofector Kit (Lonza, Cologne, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After transduction and two weeks of growth in selective medium, T2 HLA-A*11:02 cells were pulsed with the A*11-specific peptide RLRAEAQVK and cells with high expression of HLA-A*11 were FACS-purified using monoclonal antibody specific for HLA-A*11 (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA). Throughout this paper the new nomenclature for HLA class I is used (46).

T2 cell incubation with synthetic peptides

The HLA-A*11 restricted RLRAEAQVK peptide from Epstein Barr virus (EBV) and the HLA-A*02 restricted NLVPMVATV peptide from cytomegalovirus (CMV) were purchased from Synthetic Biomolecules (San Diego, CA). 106 T2 cells were incubated overnight in 500μl of serum-free medium with peptide at a final concentration of 100 μM. To assess cell surface expression of HLA-A*11:02 by peptide-pulsed cells, the cells were first incubated with unconjugated monoclonal anti-HLA-A*11 antibody (reconstituted in 100μl of distilled water and 2μl used per test) (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA) followed by goat-anti-mouse FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (10μg/ml) (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL), and then analyzed by flow cytometry.

Assay of NK cell cytotoxicity

NKL-mediated cell lysis was assessed in the standard 4-hour chromium release assay, as described (21). Effector cells were incubated with 51Cr-labeled target cells at various effector-to-target cell ratios. For antibody inhibition experiments, 51Cr-labeled 221-A*11:02 target cells (106) were incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C in 10 μl of undiluted anti-HLA-A*11 monoclonal antibody (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA) and then washed two times before incubation with effector cells. Following four hours of incubation at 37 °C, cell supernatants were harvested and 51Cr content was quantified using a Wallac γ-counter (Wallac, Turku, Finland). Specific lysis was calculated using the formula (specific release - spontaneous release)/(total release - spontaneous release). Each set of conditions was performed in triplicate; each experiment was independently replicated three or more times.

Generation of KIR-Fc fusion proteins

Wildtype and mutant KIR-Fc fusion proteins and mutants were generated according to published protocols (21, 47). The insect cell lines Sf9 and Hi5 (kindly provided by Dr K. Chris Garcia, Stanford University, CA) were cultured as described (48). Regions encoding the Ig-like domains and the stem of KIR2DL1*003 and KIR2DL3*001 were fused with the region encoding the Fc portion of the human IgG1 heavy chain. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed with the QuikChange Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The chimeric constructs were transferred into the pACgp67 vector and cotransfected into Sf9 cells with linearized baculovirus (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), using Cellfectin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After two rounds of amplification, high-titer virus was used to infect Hi5 cells for 72 hours. Cell supernatant was then collected, filtered and neutralized with HEPES buffered saline. After overnight incubation with protein A conjugated to Sepharose beads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) the beads were washed with PBS, and the KIR-Fc fusion proteins were then eluted from the beads with 0.1M glycine (pH 2.7) and immediately neutralized using 0.2M Tris-base (pH 9.0).

Binding assay of KIR-Fc fusion proteins to beads coated with HLA class I

KIR-Fc fusion proteins were tested for binding to a panel of microbeads, each bead being coated with one of 95 HLA class I allotypes: 29 HLA-A, 50 HLA-B, and 16 HLA-C (LABScreen single-Ag bead sets, One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA). These beads were originally developed for studying the specificity of human alloantibodies (49, 50) and were subsequently adapted by our group for the study of KIR specificity (21). The HLA class I proteins that coat the beads are purified from EBV-transformed B cell lines and are therefore highly heterogeneous with regard to bound peptide.

KIR-Fc fusion proteins at a concentration of 100 μg/ml were incubated with LABScreen microbeads for 60 min at 4°C on a shaker. After three washes, secondary staining with anti-human Fc-PE (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA) was performed for 60 minutes. Samples were then analyzed on a Luminex 100 reader (Luminex Corp., Austin, TX). Independently, the beads were incubated with W6/32 (50μg/ml) an anti-HLA class I antibody that recognizes an epitope shared by HLA-A, -B and –C variants (51), which showed strong binding to all 95 microbeads, and with limited variability (<20%) in the amount bound. To take account of differences in the amount of HLA class I protein coating each bead, the binding obtained with KIR was normalized to the binding obtained with W6/32. Thus the binding avidities for KIR-Fc were expressed as relative fluorescence ratios, and calculated using the formula (specific binding – bead background fluorescence)/(W6/32 binding – bead background fluorescence), to normalize KIR-Fc binding to the amount of HLA class I on each bead type. Comparison of the specificity and avidity of W6/32 for HLA class I with other monoclonal anti-HLA class I, particularly the anti-β2-microglobulin antibody BBM1 (52) that recognizes an epitope away from the polymorphic HLA class I heavy chain and involving arginine 45 of β2-m (53), is consistent with W6/32 recognizing an epitope shared by all HLA-A, B and C allotypes (54, 55).

Results

Six positively selected residues in the HLA-binding site of lineage III KIR

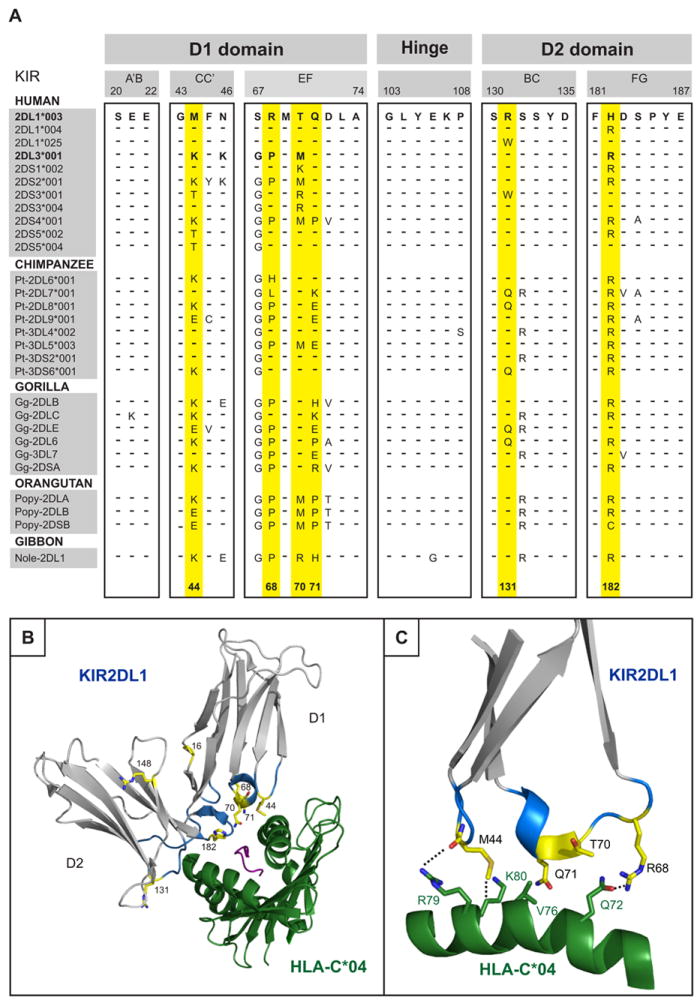

KIR of phylogenetic lineage III, which includes all the KIR that recognize HLA-C, comprises three inhibitory receptors (KIR2DL1, 2 and 3) and five activating receptors (KIR2DS1, 2, 3, 4 and 5). In addition to sequence variation among the different receptors, all of them exhibit allelic polymorphism, but to a varying degree (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ipd/kir/). To identify sites of sequence variation that have been subject to natural selection, we previously performed maximum-likelihood analysis on the aligned sequences of 110 lineage III KIR from humans and apes (7). Positive diversifying selection was evident at 16 sites in the extracellular, ligand-binding domains of the KIR molecule: positions 6, 13, 16, 44, 50, 68, 70, 71, 84, and 90 in the D1 domain; and positions 119, 123, 131, 148, 182 and 190 in the D2 domain. Examination of the crystallographic structures of HLA-C bound to KIR2DL (41, 56) showed that six of the positively selected residues lay within regions that directly contact HLA class I (Fig. 1A, B): positions 44, 68, 70 and 71 in the D1 domain (Fig. 1C) and positions 131 and 182 in the D2 domain. These positions were therefore chosen for further study.

Figure 1. Six positively selected residues in the binding site of hominoid lineage III KIR.

(A) Alignment of partial amino acid sequences of hominoid lineage III KIR showing the loops of the D1 and D2 domains that contact HLA-C. Sequences were aligned to 2DL1*003, identities being indicated by dashes (–). The six positively selected residues in the binding site for HLA class I are colored yellow, as is also the case for panels B and C. (B) Ribbon diagram of KIR2DL1 (grey) bound to HLA-C*04:01 (green) (PDB1IM9) (56). The loops of the KIR molecule are colored blue and positively selected residues are colored yellow. (C) Details of the binding between the D1 domain contact loop of KIR2DL1*003 (in blue with positively selected residues in yellow) and the α1 domain helix of HLA-C*04:01 (green).

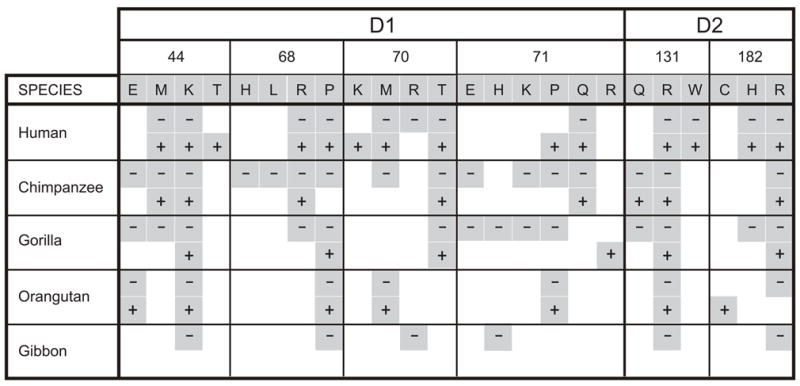

For these six positions, sequence variability is notably higher in the D1 domain than the D2 domain, both in the number s of positively-selected positions and the number of alternative residues at each position (Fig. 2). Nonetheless, there is a variety of residues with distinctive chemistry and functional potential at all six positions. Lysine 44, proline 68, arginine 131 and arginine 182, are the only residues present in all five hominoid species examined, consistent with them having been present in the common hominoid ancestor. Greater variability and species-specificity is observed for positions 70 and 71. Position 70 stands out for its diversification in humans but relative conservation in other species, whereas position 71 is more variable in chimpanzees and gorillas than humans, particularly for the inhibitory KIR (Fig. 2). Given these properties, we hypothesized that variation at these six positions had been selected for its direct effect on the functional interactions of hominoid lineage III KIR with MHC class I. To test this hypothesis we introduced all naturally occurring variations at the six positions (Fig. 2) into human C2-specific KIR2DL1 and C1-specific KIR2DL3, and then determined the effects of these mutations on KIR specificity and avidity for HLA class I.

Figure 2. Sequence variation in human and ape lineage III KIR at each of the six positively selected positions located within the binding site for MHC-C.

For each of the six positions (44, 68, 70, 71, 131, and 182) the variety of residues is shown. For each species, the presence of a given residue in their KIR is indicated by a grey-shaded box; a box with a dash (-) denotes its presence in inhibitory KIR, a box with a plus sign (+) denotes its presence in activating KIR.

Fc fusion proteins were made from the mutant and wild-type KIR and tested for binding to 95 HLA class I allotypes, using a robust, sensitive assay in which the target are microbeads, each coated with a single HLA class I allotype (13, 21, 40, 43, 57). Being purified from EBV-transformed B cell lines, each single HLA class I allotype is highly diverse with regard to the sequence of the bound peptide (49).

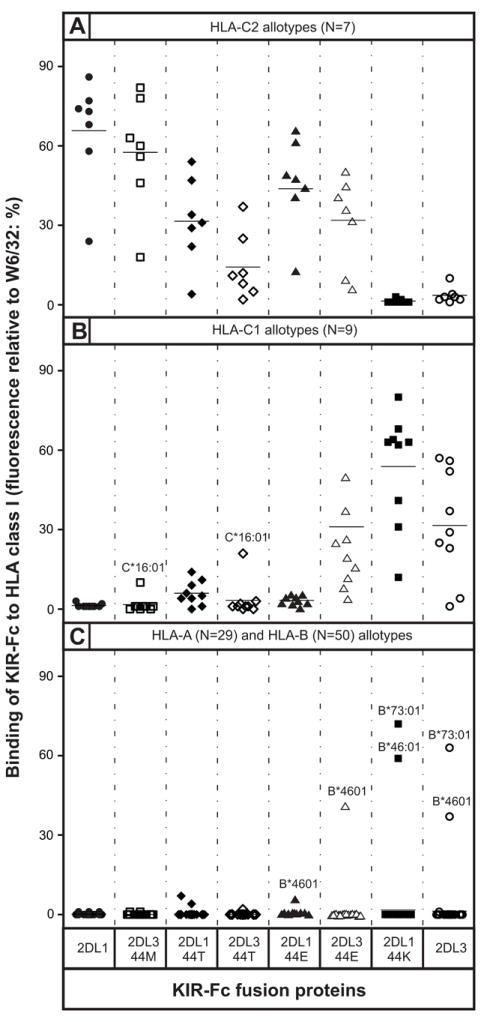

Variation at position 44 modulates specificity and strength of KIR recognition of MHC-C

Consistent with previous studies (22, 23), we find that swapping the position 44 residues of KIR2DL1 and KIR2DL3 is sufficient to swap their HLA class I specificities. Thus the 2DL3-44M mutant has C2 specificity like KIR2DL1 (Fig. 3A) and the 2DL1-44K mutant has C1 specificity like KIR2DL3 (Fig. 3B). Two exceptional HLA-B allotypes, B*46:01 and HLA-B*73:01, also carry the C1 epitope (21, 58) and bind well to both KIR2DL3 and mutant 2DL1-44K (Fig. 3C). It is on the basis of data such as these that position 44 has been described as the specificity determining position of the lineage III KIR (22, 23).

Figure 3. The residue at position 44 determines the HLA-C specificity of lineage III KIR.

Shown are the results of assays to measure the binding of wild-type and mutant KIR2DL1-Fc and KIR2DL3-Fc fusion proteins to beads coated with a representative range of HLA-A, -B, and -C allotypes. Mutations were restricted to position 44 where KIR2DL1 has methionine and KIR2DL3 has lysine. Fusion proteins tested were: 2DL1 (●), 2DL3-44M (□), 2DL1-44T (◆), 2DL3-44T (◇), 2DL1-44E (σ), 2DL3-44E (△), 2DL1-44K (■), and 2DL3-WT (○). Shown are representative results from (A) 7 C2-bearing HLA-C allotypes; (B) 9 C1-bearing HLA-C allotypes, and (C) 29 HLA-A and 50 HLA-B allotypes. The mean value for each allotype group is denoted by a horizontal line. Allotypes showing unusual patterns of binding are indicated by their official names (46).

On average, the binding of KIR2DL1 to C2 (Fig. 3A) was around twice that of KIR2DL3 to C1 (Fig. 3B), indicating that KIR2DL1 is a stronger receptor than KIR2DL3. That mutant 2DL1-44K bound C1 at a much higher level (180%) than KIR2DL3 (Fig. 3B) confirms that 2DL1 is an inherently stronger receptor, and that substitutions other than the lysine-methionine dimorphism at position 44 contribute to the avidity difference. However, the observation that mutant 2DL3-44M binds C2 almost as well (85%) as KIR2DL1 shows clearly that methionine 44 must also contribute to KIR2DL1 having higher avidity than KIR2DL3 (Fig. 3A). Consistent with this proposition, the mean binding of mutant 2DL1-K44 to C1 is 83% of that achieved by 2DL1 to C2, a comparison in which the only difference between the two KIR-Fc is at position 44 (Figure 3). Likewise the mean binding of 2DL3 to C1 (not including the poorly reactive HLA-C*12:03 and HLA-C*14:02) is 69% of that achieved by 2DL3-M44 binding to C2 (Figure 3). These comparisons show that methionine 44 produces a stronger avidity than lysine 44, consistent with the qualitatively different bonding patterns observed between KIR residue 44 and HLA-C residue 80 in the crystallographic structures of complexes of KIR2D and HLA-C (41, 56, 59).

Threonine 44 is naturally present in KIR2DS3 and KIR2DS5 (Fig. 1A), activating receptors exhibiting no detectable avidity for any HLA class I when tested in the same binding assay as that used here (40). In contrast, KIR2DL1 and KIR2DL3 mutants with threonine 44 recognize some HLA-C allotypes. Replacement of lysine 44 by threonine in KIR2DL3 (mutant 2DL3-44T) abrogated binding to C1, with the exception of C*16:01 which retained ~50% of binding (Fig. 3B). Accompanying the loss of C1 reactivity was acquisition of C2 specificity by 2DL3-44T, but with much lower avidity than KIR2DL1 or 2DL3-44M (Fig. 3A). The 2DL1-44T mutant retained the C2 specificity of KIR2DL1, but with avidity reduced by ~50%. The avidity of 2DL1-44T for C2 was greater than that of 2DL3-44T, the same hierarchy as observed for the 2DL1 and 2DL3 mutants with methionine and lysine at position 44. Moreover, the avidity of 2DL1-44T for C2 (Fig. 3A) is comparable to that of 2DL3 for C1 (Fig. 3B), well within the functional range of inhibitory NK cell receptors. Thus human lineage III KIR with threonine 44 have the potential to be C2-specific receptors, suggesting that KIR2DS3 and KIR2DS5, for which ligands remain unknown (40, 60, 61), evolved from activating C2 receptors that lost the capacity to bind HLA class I through selected substitutions at positions other than 44. That threonine 44 is present only in human lineage III KIR, points to these receptors having both arisen and become attenuated during the course of human evolution.

Although orangutan, gorilla and chimpanzee have KIR with glutamate 44, such KIR were lost during human evolution (Fig. 2). Mutant 2DL1-44E retained the C2 specificity of KIR2DL1 but with 36% loss of avidity (Fig. 3A), properties similar to those of chimpanzee KIR2DL9 that has glutamate 44 (62). In contrast, mutant 2DL3-44E acquired reactivity with C2, while retaining 87% of the avidity for C1. Consequently, 2DL3-44E binds with comparable avidity to C1 and C2, thus having pan specificity for HLA-C (Fig. 3A and 3B). This C1+C2 specificity of 2DL3-44E is very similar to that of Popy-2DLB and Popy-2DSB, paired inhibitory and activating orangutan KIR that have glutamate 44 (38). The only difference between 2DL3-44E and the orangutan KIR is in the recognition of the two C1-bearing HLA-B allotypes; the orangutan KIR recognize both HLA-B*46:01 and HLA-B*73:01, whereas 2DL3-44E recognizes only HLA-B*46:01 (Fig. 3C).

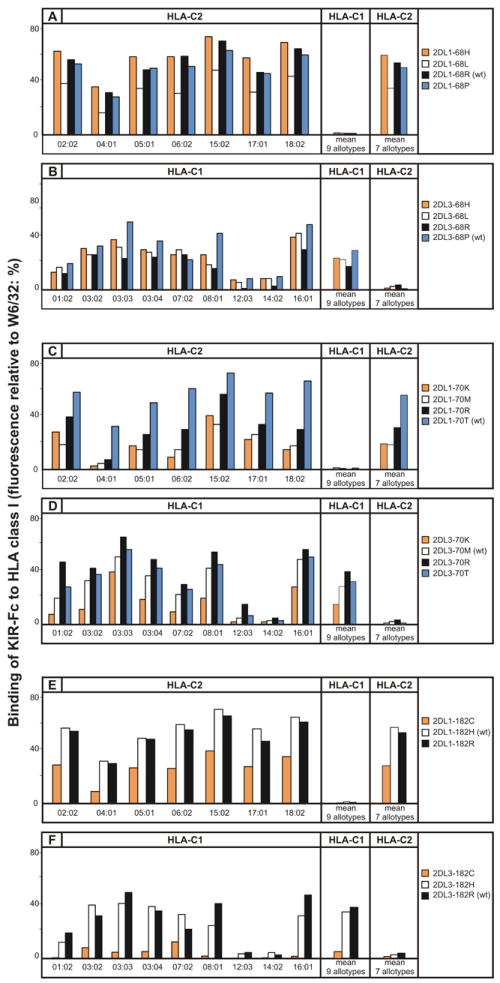

Variation at positions 68, 70, and 182 modulates the avidity of KIR2DL for MHC-C

Substitution at position 68 did not perturb the specificities of KIR2DL1 and KIR2DL3 for HLA-C, but did affect their avidities for HLA-C. Mutation of arginine 68 in KIR2DL1 to histidine or proline (the residue present in KIR2DL3) had little effect, but mutation to leucine reduced the avidity by 34% while preserving C2 specificity (Fig. 4A). For KIR2DL3, mutation of proline 68 to histidine, leucine or arginine reduced the avidity for C1 by 19-40% (mean of 27%), while preserving C1 specificity (Fig. 4B). KIR2DL3 is thus seen to be more sensitive to substitution at position 68 than KIR2DL1.

Figure 4. The avidity of KIR2D for MHC-C has been modulated by positive selection at positions 68, 70, and 182.

Shown is the binding of wild-type (wt) and mutant KIR2DL-Fc fusion proteins to beads coated with 16 HLA-C allotypes: 9 having the C1 epitope (HLA-C1) and 7 the C2 epitope (HLA-C2). Binding to each HLA-C allotype is given (left), as well as mean values for the HLA-C1 and HLA-C2 allotype groups (right). (A) Mutation at position 68 of KIR2DL1: 2DL1-68H (orange shading), 2DL1-68L (white shading), 2DL1-68R (wt) (black shading), 2DL1-68P (blue shading). (B) Mutation at position 68 of KIR2DL3: 2DL3-68H (orange shading), 2DL3-68L (white shading), 2DL3-68R (black shading) and 2DL3-68P (wt) (blue shading). (C) Mutation at position 70 of KIR2DL1: 2DL1-70K (orange shading), 2DL1-70M (white shading), 2DL1-70R (black shading) and 2DL1-70T (wt) (blue shading). (D) Mutation at position 182 of KIR2DL3: 2DL3-70K (orange shading), 2DL3-70M (wt) (white shading), 2DL3-70R (black shading) and 2DL1-70T (blue shading). (E) Mutation at position 182 of KIR2DL1: 2DL1-182C (orange shading), 2DL1-182H (wt) (white shading) and 2DL1-182R (black shading) and (F) Mutation at position 182 of KIR2DL3: 2DL3-182C (orange shading), 2DL3-182H (white shading) and 2DL3-182R (wt) (black shading). HLA-C*12:03 and C*14:02, routinely bind weakly compared to other C1-bearing allotypes.

Substitutions at position 70 had no effect on either the C2 specificity of KIR2DL1 or the C1 specificity of KIR2DL3, but altered their avidities to a greater extent than seen for the position 68 mutations. Substitution of threonine 70 in KIR2DL1 to lysine, methionine or arginine reduced the avidity by 43-66%, the greatest effect being seen with methionine, the residue present at position 70 in KIR2DL3 (Fig. 4C). In contrast, substitution of methionine 70 in KIR2DL3 with arginine or threonine (the residue present in KIR2DL1) gave a modest increase (16-38%) in the avidity for C1, whereas lysine substitution reduced the avidity by 48% (Fig. 4D). The results obtained for the position 70 swap mutants indicate that the threonine-methionine difference at position 70 is a major factor contributing to the higher avidity of KIR2DL1 and lower avidity of KIR2DL3.

Substitution of histidine 182 in KIR2DL1 for arginine (the residue in KIR2DL3) had no effect, whereas substitution for cysteine reduced the avidity for C2 by 50% (Fig. 4E). The effect of the cysteine substitution in KIR2DL3 was even greater. When arginine 182 of KIR2DL3 was replaced by cysteine the avidity for C1 was reduced by 87%, whereas the introduction of histidine had only modest effect (10% reduction) (Fig. 4F). A common property of the mutations at positions 68, 70, and 182 is that they affect the avidity, but not the specificity, of the receptors. For KIR2DL1 these mutations led only to retention or reduction of avidity for C2, whereas for KIR2DL3, they could also lead to increased avidity for C1. Comparison of the properties of the swap mutations between 2DL1 and 2DL3 at positions 68, 70, and 182 indicates that the difference at position 70 contributes significantly to the differential avidity of the two receptors, whereas the effects of the reciprocal substitutions at positions 68 and 182 are weaker and less clear cut.

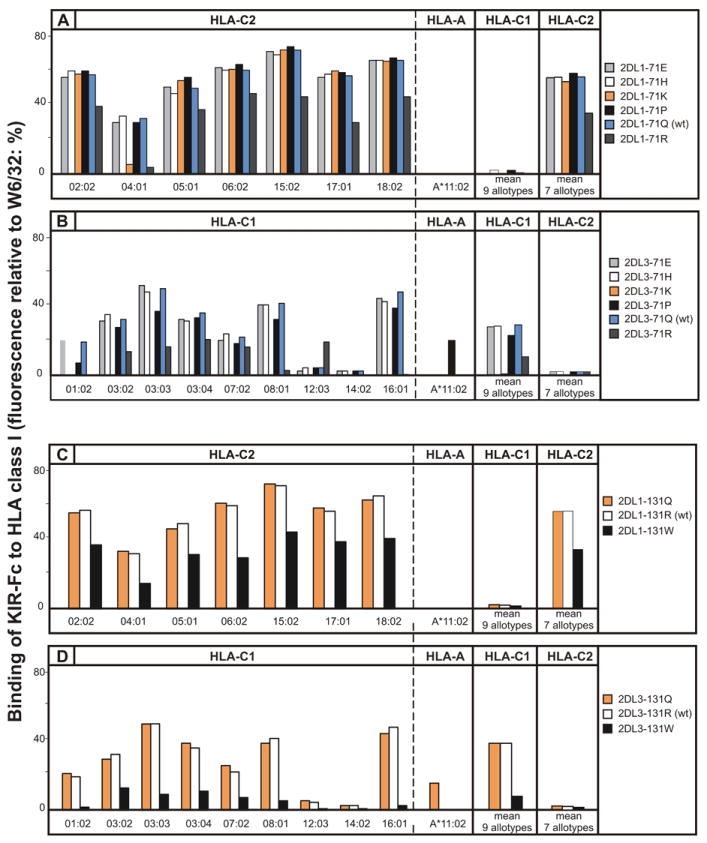

Position 71 and 131 variation can alter avidity for HLA-C and introduce recognition of HLA-A*11:02

Both KIR2DL1 and KIR2DL3 have glutamine 71. In KIR2DL1 its substitution with glutamate, histidine, and proline had little effect on the specificity or avidity for C2. In contrast, the 2DL1-71R mutant exhibited a general reduction of avidity, while preserving C2 specificity (Fig. 5A). For HLA-C*04:01 the avidity was diminished by 88% and for other C2-bearing allotypes the reduction was 38% (Fig. 5A). For the 2DL1-71K mutant this selective trend was more extreme: binding to HLA-C*04:01 was reduced by 82%, whereas the binding to other C2-bearing allotypes was unperturbed.

Figure 5. Positive selection at positions 71 and 131 of KIR2D can introduce reactivity with HLA-A*11:02 and alter avidity for HLA-C.

Shown is the binding of wild-type (WT) and mutant KIR2D-Fc fusion proteins to beads coated HLA-C (9 HLA-C1 and 7 HLA-C2) and A*11:02 allotypes. (A) Mutation at position 71 of KIR2DL1: 2DL1-71E (light-grey shading), 2DL1-71H (white shading), 2DL1-71K (orange shading), 2DL1-71P (black shading), 2DL1-71Q (wt) (blue shading), 2DL1-71R (dark-grey shading). (B) Mutation at position 71 of KIR2DL3: 2DL3-71E (light-grey shading), 2DL3-71H (white shading), 2DL3-71K (orange shading), 2DL3-71P (black shading), 2DL3-71Q (wt) (blue shading), 2DL3-71R (dark-grey shading). (C) Mutation at position 131 of KIR2DL1: 2DL1-131Q (orange shading), 2DL1-131R (wt) (white shading), 2DL1-131W (black shading). (D) Mutation at position 131 of KIR2DL3: 2DL3-131Q (orange shading), 2DL1-131R (wt) (white shading), 2DL1-131W (black shading). HLA-C*12:03 and C*1402, routinely bind weakly compared to other C1-bearing allotypes.

Replacing glutamine 71 in KIR2DL3 with either glutamate or histidine had little effect on C1 specificity or avidity. In contrast, lysine 71 abrogated the interaction of KIR2DL3 with C1 and arginine 71 reduced the mean avidity for C1 by 64% while increasing the avidity for C1-bearing HLA-C*12:03 (Fig. 5B). Proline 71 caused a modest decrease in the avidity for C1 (25%), but broadened the specificity of mutant 2DL3-71P to include HLA-A*11:02 (Fig. 5B). KIR2DS4 is an activating lineage III KIR that naturally has proline 71 and exhibits similar reactivity with HLA-A*11:02 (43). However, proline 71 is not necessary for recognition of HLA-A*11:02, as became apparent from analysis of the position 131 mutants (Fig. 5C and 5D). Substitution of arginine 131 in KIR2DL3 with glutamine introduced reactivity with HLA-A*11:02 while preserving avidity for C1-bearing HLA-C (Fig. 5D). In contrast, substitution of arginine 131 for tryptophan caused 86% loss of avidity for C1, but no binding to HLA-A*11:02. For KIR2DL1, replacement of arginine 131 by glutamine preserved the avidity and specificity for C2, with no acquisition of reactivity towards HLA-A*11:02, while replacement with tryptophan preserved a pure C2 specificity, but reduced in avidity by 40% (Fig. 5C).

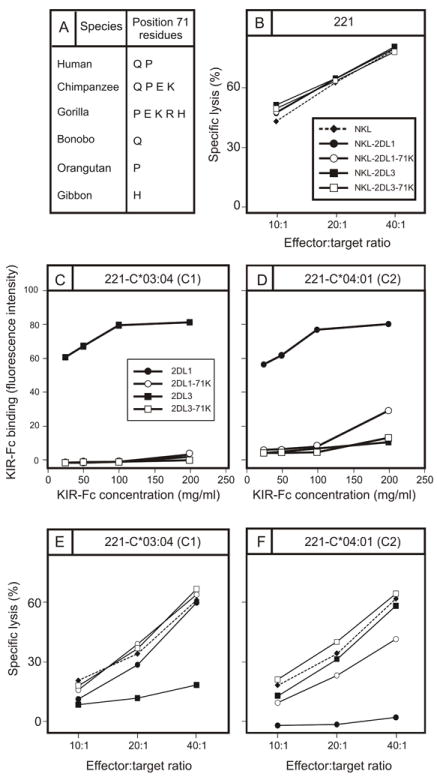

In structural and functional studies of KIR interaction with HLA-C it has been common practice to use HLA-C*04:01 as the prototypical C2-bearing allotype (23, 56, 63). As the selective loss of HLA-C*04:01 reactivity by 2DL1-71K and 2DL1-71R (Fig. 5A) implies that HLA-C*04:01 has unusual properties, we investigated the capacity of 2DL1-71K to recognize HLA-C*04:01 in a functional assay of NK cell killing. NKL cells transduced with 2DL1, 2DL1-71K, 2DL3, and 2DL3-71K, lysed untransfected 221 cells effectively and to similar degree (Fig. 6B). KIR-Fc fusion constructs made from 2DL1, 2DL1-71K, 2DL3, and 2DL3-71K, bound to transfected 221 cells expressing HLA-C*03:04 (C1) and HLA-C*04:01 (C2) with similar specificities and avidities to those obtained in the bead-binding assay. Thus, KIR2DL3 bound to 221-C*03:04 (Fig. 6C) but not to 221-C*04:01 (Fig. 6D), whereas KIR2DL1 bound to 221-C*04:01 (Fig. 6D) but not 221-C*03:04 (Fig. 6C). No binding of 2DL3-71K was detected on either target cell, whereas 2DL1-71K bound weakly but specifically to 221-C*04:01 (Fig. 6D). In cytolytic assays, 221-C*03:04 cells were resistant to lysis by NKL cells expressing KIR2DL3, but were killed by NKL cells expressing KIR2DL1, 2DL1-71K, or 2DL3-71K (Fig. 6E). Conversely, 221-C*04:01 cells were resistant to lysis by NKL cells expressing KIR2DL1, but were killed by NKL cells expressing either KIR2DL3 or 2DL3-71K (Fig. 6F). NKL cells expressing 2DL1-71K lysed 221-C*04:01 cells to a much lesser extent than KIR2DL1, consistent with its weak but detectable signal in the binding assay (Fig. 6D). In conclusion, a positive correlation was observed between the results obtained in the direct binding assay and functional assays of cellular cytotoxicity. Consequently, our analysis points to HLA-C*04:01 having unusual properties, that could challenge its prototypical stature.

Figure 6. Lysine 71 abrogates interaction of KIR2DL3 with HLA-C and selectively impairs interaction of KIR2DL1 with HLA-C*04:01.

(A) Shown are the residues present at position 71 in hominoid lineage III KIR. Notably lysine 71 is absent from humans but present in chimpanzees and gorillas. (B) Killing of class I-deficient 221 cells by NKL cells (◆, broken line), and by NKL cell transduced with KIR2DL1 (●), 2DL1-71K (○), KIR2DL3 (■), and 2DL3-71K (□). (C,D) Binding to 221 cells expressing C1-bearing HLA-C*03:04 (C) and C2-bearing HLA-C*04:01 (D) of KIR2DL-Fc fusion proteins: KIR2DL1 (●), 2DL1-71K (○), 2DL3 (■), and 2DL3-71K (□). (E, F) Killing of 221 target cells expressing HLA-C*03:04 (E) and HLA-C*04:01 (F) by NKL cells expressing KIR2DL1 (●), 2DL1-71K (○), 2DL3 (■), and 2DL3-71K (□).

Functional recognition of HLA-A*1102 by mutant KIR2DL3-71P

Of the four HLA class I epitopes (A3/11, Bw4, C1 and C2) recognized by KIR, A3/11 is the one for which the functional significance remains uncertain. Carried by HLA-A*03 and HLA-A*11 allotypes, the A3/A11 epitope was first shown to engage the lineage III KIR, KIR3DL2 (28, 64). Whereas Bw4, C1 and C2 mediate robust inhibition and education of NK cells on binding their cognate KIR, the interaction of the A3/11 with 3DL2 gives weak inhibition (25) and no detectable education (65, 66). In previous studies of lineage III KIR2DS4 (43) and orangutan lineage III (13) we have detected binding HLA-A allotypes carrying the A3/11 epitope, for which the strength of binding is A*11:02>A*11:01>A*03:01. This hierarchy is again seen for mutant 2DL3-71P, which binds significantly to A*11:02, but not to A*11:01 or A*03:01 (Figure 6A). With this background and context, we tested if the recognition of HLA-A*11:02 by 2DL2-71P could influence NK cell function.

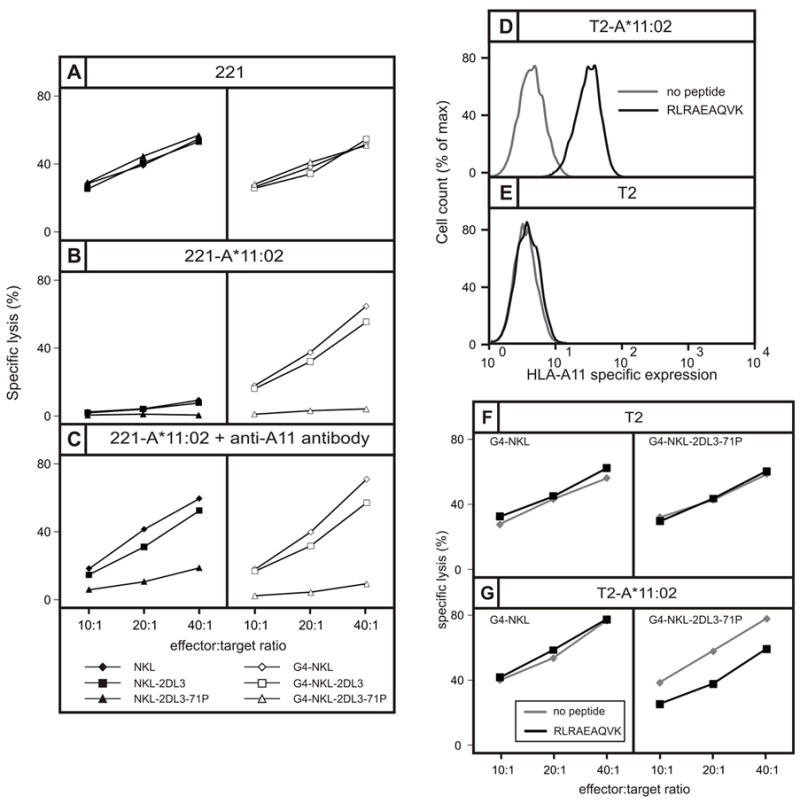

In cytotoxic assays, NKL cells killed 221 cells (Fig. 7A) but not 221 cells transfected with HLA-A*11:02 (Fig. 7B), an inhibitory effect never saw with 221 cells expressing either C*03:04 or C*04:01 (20) (Fig. 6E, F). As the leader peptides of the transfected HLA class I are all non-permissive for HLA-E interaction with CD94:NKG2A, the enhanced inhibition of cytolysis achieved by A*11:02 was unlikely to be mediated through this receptor. Alternatively, the inhibition could arise from interaction of HLA-A*11:02 with the LILRB1 receptor on NKL. Consistent with this mechanism, G4-NKL a derivative of NKL having siRNA that reduces LILRB1 expression by >90% killed 221-A*11:02 cells much more effectively than NKL (Figure 7B). Our observations that HLA-C*03:04 and HLA-C*04:01 are not good functional ligands for LILRB1 agree with the results of previous studies. Using a similar assay system, LILRB1 was seen to bind HLA-G, HLA-A*03:01, B*27:02, and B*27:05, but not HLA-C*03:01 (67). Likewise, a LILRB1-Fc fusion protein bound well to a variety of HLA-A and –B allotypes at cell surfaces, but not to HLA-C*04:01 or C*07:02, and only weakly to C*03:04 (68). By contrast, in non-cellular binding assays LILRB1 has detectable avidity for the spectrum of HLA-C allotypes (69, 70). The mechanisms underlying the differing results obtained in cellular and molecular binding assays, and between HLA-A and –B compared to HLA-C, have yet to be determined. To identify and avoid the inhibitory effects of LILRB1, our experiments to investigate the capacity for HLA-A*11:02 to be a KIR ligand were performed using both NKL (Fig. 7A, B, and C, left) and G4-NKL cells (Fig. 7A, B, and C, right).

Figure 7. Proline 71 present in KIR2DS4 and KIR3DL2 confers specificity for HLA-A*11:02 on KIR2DL3 but not on KIR2DL1.

(A, B and C) Shows the results of cytotoxicity assays in which the target cells are (A) class I deficient 221 cells, (B) 221 cells expressing HLA-A*11:02, or (C) 221 cells expressing HLA-A*11:02 cells pre-incubated with antibody specific for HLA-A*11. In the panels on the left the effector cells are NKL cells (◆), NKL cells expressing 2DL3 (■), and NKL cells expressing 2DL3-71P (σ). In the panels on the right the effector cells are G4-NKL cells (◇), G4-NKL cells expressing 2DL3 (□), and G4-NKL cells expressing 2DL3-71P (△). NKL cells express the HLA class I receptor LILRB1, whereas G4-NKL is a NKL cell in which LILRB1 expression is suppressed. (D, E) Flow cytometric analysis of the binding of anti-A*11 antibody to (D) T2 cells transfected with HLA-A*11:02 (T2-A*11:02) and (E) untransfected T2 cells, following overnight incubation in the presence (black line) or absence (grey line) of the RLRAEAQVK peptide that binds HLA-A*11 (black histogram). (F, G) Shows the results of cytotoxicity assays in which the targets were (F) T2-A*11:02 cells and (G) T2 cells, following overnight incubation in the presence (black line) or absence (grey line) of peptide RLRAEAQVK. Effector cells were G4-NKL cells (left) and G4-NKL cells expressing 2DL3-71P.

That G4-NKL cells expressing KIR2DL3 killed 221-A*11:02 cells shows A*11:02 is not a ligand for wild type KIR2DL3 (Fig. 7B right). In contrast, killing of 221-A*11:02 was strongly inhibited when G4-NKL cells expressed the 2DL3-71P mutant, showing that binding of A*11:02 to 2DL3-71P is a functional ligand-receptor interaction that leads to the transduction of an inhibitory signal (Fig. 7B right). Pre-incubation of 221-A*11:02 with an anti-A11 monoclonal antibody had little effect on the interaction between 2DL3-71P and HLA-A*11:02 (Fig. 7C right), but rendered the cells susceptible to lysis by NKL cells, with an efficiency similar to that achieved by siRNA-mediated down-regulation of LILRB1 (Fig. 7C left). This result, suggesting the antibody recognizes an epitope of HLA-A*11:02 in or near the binding site for LILRB1, but away from the binding site for KIR2DL3-71P, is consistent with crystallographic studies showing that LILRB1 interacts with the conserved Ig-like domains (α3 and β2-microglobulin) of HLA class I (71), whereas lineage III KIR interact with the highly polymorphic α1 and α2 domains (59).

Mutant KIR2DL3-71P can recognize the complex of HLA-A*11:02 and a peptide derived from Epstein-Barr virus

Comparison of five peptides that bind to HLA-A*03:01 and five peptides that bind to HLA-A*11:01 showed that peptide RLRAEAQVK from the EBNA3A protein of EBV, which binds both A*03:01 and A*11:01, was the only peptide that permitted interaction with KIR3DL2 (72-74). With this precedent, we investigated whether this peptide could bind to HLA-A*11:02 and form a functional ligand for the KIR2DL3-71P mutant. To do this, we transfected the TAP-deficient T2 cell line with A*11:02. T2 cells present very few endogenous peptides, giving a minimal surface expression of HLA class I unless binding peptide is supplied exogenously. In the absence of peptide, basal expression of A*11:02 on transfected T2 cells was undetectable (Figure 7E). T2 and T2-A*11:02 cells were incubated overnight either in the absence or presence of peptide RLRAEAQVK (73). Incubation of T2-A*11:02 cells with peptide increased the amount of A*11:02 on the cell surface ten-fold over T2-A*11:02 cells incubated in the absence of peptide (Fig. 7D) or T2 cells incubated either in the presence or absence of peptide (Fig. 7E). This result shows that A*11:02 does bind the RLRAEAQVK peptide. (Figure 7F). Consequently, the substitution of lysine for glutamate at position 19 that distinguishes HLA-A*11:02 from A*11:01 does not affect the binding of this peptide.

In cytotoxicity assays, T2 cells that were incubated in the presence or absence of peptide were killed to similar extent by G4-NKL cells and G4-NKL cells expressing the 2DL3-71P mutant (Fig. 7F). G4-NKL and G4-NKL-2DL3-71P gave a similarly effective killing of T2-A*11:02 cells that had been incubated in the absence peptide. In contrast, T2-A*11:02 cells that had been incubated with peptide exhibited a resistance to killing by G4-2DL3-71P (Fig.7G). This result indicates that 2DL3-71P recognizes the complex of RLRAEAQVK bound to A*11:02 to generate a functional signal that inhibits NK cells.

Discussion

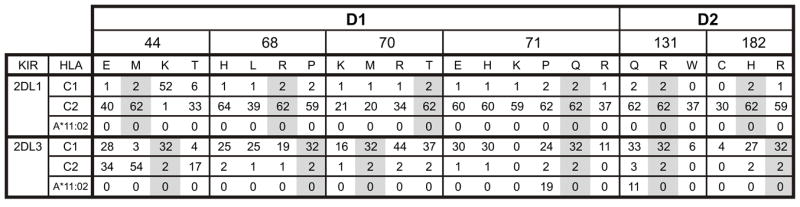

MHC-C mediated regulation of NK cells is of recent and rapid evolution and specific to hominids: humans and great apes. In humans comprises a bipartite system in humans of two mutually exclusive epitopes that are defined by dimorphism at position 80 of HLA-C and which serve as ligands for different lineage III KIR (15, 19, 31). Here we compared KIR2DL3 that recognizes the C1 epitope (asparagine 80) with KIR2DL1 that recognizes the C2 epitope (lysine 80). Comparison of >100 hominid lineage III KIR identified six positions of sequence variation that have been subject to positive diversifying selection and are situated in the part of the KIR molecule that forms the binding site for HLA-C, as visualized at high resolution in three-dimensional crystallographic structures (56, 59, 75). To assess the effects of natural selection upon the interactions of KIR with MHC-C, we studied the strength and specificity of mutant KIR2DL3 and KIR2DL1 receptors, each one substituted with one of the natural variations identified at the six positively selected sites. Each wild-type receptor was thus compared to 18 mutants. The results of this analysis are summarized in Figure 8.

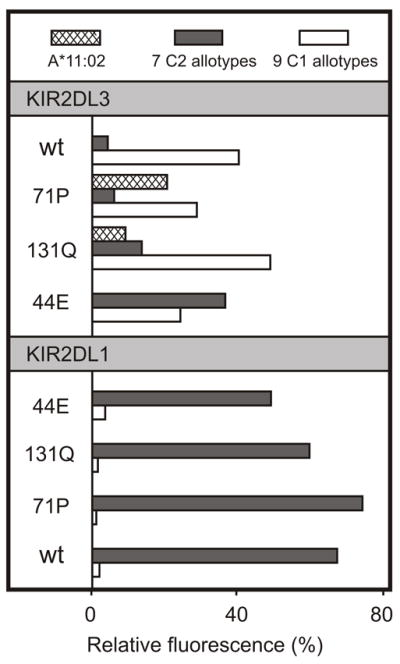

Figure 8. Summary of the binding avidity of KIR2DL1 and KIR2DL3 mutants for the C1 and C2 epitopes of HLA-C and for HLA-A*1102.

Each value is the binding of the KIR-Fc protein to the target HLA class I expressed as a percentage of the binding of the W6/32 monoclonal to the same HLA class I. Values for C1 and C2 are the means from 9 C1-bearing and 7 C2-bearing HLA-C allotypes, respectively. Grey shading indicates the residues in wild type KIR2DL1*003 and KIR2DL3*001.

Overall, mutation had a wider range of effects on KIR2DL3 than KIR2DL1. The C1 specificity of KIR2DL3 was changed in two ways: the first, a major broadening to give a pan HLA-C receptor with C1 plus C2 specificity; the second, a minor broadening to give reactivity with HLA-A*11:02 as well as C1. The avidity of KIR2DL3 was also changed in two ways: two of the mutations increased avidity for C1 by >10%, 13 decreased the avidity by >10%, and three had little effect (Fig. 8) In comparison to KIR2DL3, the ligand-binding properties of KIR2DL1 were more resistant to mutation: none of the 18 mutations altered the C2 specificity, and none of them increased the avidity for C2. Ten mutations in KIR2DL1 reduced C2 avidity by >10%, and eight had little effect. Consideration of all the mutants except those at specificity-determining position 44, shows that all KIR2DL1 mutants retained a minimum of 32% of the wild type binding with an average of 75%, whereas the KIR2DL3 mutants ranged from 0-138% of wild-type binding with an average of 68%. Exemplifying the variety of effects that mutation had on KIR2DL3 and their limited effect on KIR2DL1, are the avidities and specificities of the mutants containing glutamate 44, proline 71, and glutamine 13 (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. KIR2DL1 has stronger avidity and narrower HLA class I specificity than KIR2DL3.

Shown is the binding of wild-type (wt) and mutant KIR2DL3- (upper) and KIR2DL1-Fc (lower) fusion proteins to beads coated with HLA-A*11:02 (cross-hatch shading), HLA-C2 allotypes (dark grey shading, mean value for 7 allotypes) and 9 HLA-C1 allotypes (white shading, mean value for 9 allotypes). The specificity and avidity of KIR2DL1 are markedly more resistant to mutation at positions 44, 71 and 131 than KIR2DL3.

In functional and epidemiological studies the interactions of KIR2DL1 with C2 and KIR2DL2/3 with C1 are often considered as complementary but equivalent. From molecular analysis a different picture emerges, one in which KIR2DL1 is seen as the stronger and more selective receptor, which appears to have been optimized for high-avidity recognition of C2 and as a consequence became relatively resistant to further functional change by point mutation. On the other hand, KIR2DL3 is seen as the weaker and less selective receptor, which by being less refined retains greater potential for improvement and change. Having acquired a strong and exquisite specificity for C2, KIR2DL1 is now specialized and inflexible; by retaining a weaker C1 specificity that cross-reacts with C2 (21, 22, 30) KIR2DL3 is less specialized but more flexible and adaptable.

These contrasting and complementary properties fit well with an evolutionary model in which the C1 epitope and their cognate C1-specific KIR evolved first and subsequently underwent mutation and selection to give rise to the C2 epitope and C2-specific KIR (38). The crucial feature of this model is the flexibility of the C1 receptor and its cross-reactivity with C2, which while maintaining function as a C1 receptor provides a potential C2 receptor prior to formation of the C2 epitope. Thus the inherent flexibility of the C1 receptor allows C2 and C2-specific KIR to evolve by stepwise point mutation through a series of intermediate forms that all have biological function and could be maintained by natural selection. The model’s first intermediate is a receptor with broad MHC-C reactivity like the 2DL3-44E mutant (Fig. 8). Presence of this C1+C2 specific receptor sets the stage for mutation at position 80 of MHC-C to produce C2 from C1 and for it to be a functional KIR ligand. With both C1 and C2 in place, further mutation of the KIR, including the key introduction of methionine 44, then gave rise to highly specific C2 receptors such as KIR2DL1.

Hominid variation at three of the six positively selected positions is associated with changes in receptor specificity: position 44 controls HLA-C specificity, positions 71 and 131 affect the recognition of HLA-A*11:02. Variation at all six positions influences receptor avidity, but the major players are positions 70 and 44. In determining both specificity and avidity, residues of the D1 domain are the dominant influence, with D2 domain residues taking the minor role. Because KIR2DL1*003 and KIR2DL3*001 are identical at positions 71 and 131, only positions 44, 68, 70, and 182 can contribute to their functional differences. That dimorphism at position 44 determines receptor specificity is well known (23), but this difference of methionine in KIR2DL1 and lysine in KIR2DL3 also contributes to their relative strength.

The major modulator of avidity is residue 70: threonine in KIR2DL1 and methionine in KIR2DL3. By rough estimate, 67% of the avidity difference comes from position 70 and 19% comes from position 44. The remaining 14% could involve synergism between positions 44 and 70, which would go undetected in this study of single mutations, or contributions from other positions, including 68, 182, and the ten positively-selected positions away from the binding site (7). Precedent being the synergistic contribution that distal residues 16 and 148 make to KIR2DL2*001 being a stronger C1 receptor than KIR2DL3*001 (21). Although residue 70 is the major influence on receptor avidity, it has no role in receptor specificity. In their respective crystallographic structures, glutamine 70 of KIR2DL1 makes no direct contact with HLA-C*04 (56, 59, 75), whereas glutamine 70 of KIR2DL2 forms a hydrophobic bond with arginine 69 of HLA-C*03. It is not known if glutamine 70 of KIR2DL3 makes a similar contact with HLA-C, because a pertinent crystallographic structure has yet to be determined

Interaction of KIR2DL3 with HLA-A*11:02 was achieved by mutation at either position 71 or 131. The A3/11 epitope, carried by HLA-A*03 and HLA-A*11, was first described as the ligand for KIR3DL2, a lineage II KIR (28, 64). Subsequently, lineage III KIR2DS4 was shown to bind HLA-A*11 but not HLA-A*03, a property associated with the proline 71 valine 72 motif acquired from a KIR3DL2-like lineage II gene, and not present in other lineage III KIR (43). We now show that introduction of proline 71 into KIR2DL3 is sufficient to confer reactivity with HLA-A*11:02, but it is not necessary to achieve this effect. Mutating arginine 131 to glutamine in KIR2DL3 also conferred recognition of HLA-A*11:02. Popy-2DLA, an orangutan receptor that has lysine 44, proline 71 and arginine 131 also recognizes HLA-A*1102. Unlike C1, C2 and Bw4, the A3/11 epitope cannot be described in terms of a single specificity-determining residue.

Of the four HLA class I epitopes recognized by KIR, the A3/11 epitope is the one least studied and for which the functional significance remains uncertain. Although all human populations have the Bw4, C1 and C2 epitopes, the A3/11 epitope appears dispensable: for example, it is absent from Native American populations (http://www.allelefrequencies.net (76)). Functionally, interactions of Bw4, C1, and C2 with cognate KIR mediate robust inhibition and education of NK cells, whereas KIR3DL2 engagement of A3/11 gives weak inhibition (25) and no detectable education (65, 66). Only one of ten viral or self peptides that binds to HLA-A*03 and/or HLA-A*11 (RLRAEAQVK from EBV) has been shown to permit interaction with KIR3DL2 (27), raising the possibility that only small fractions of the HLA-A*11 and HLA-A*03 molecules on cell surfaces function as ligands for KIR3DL2. The biological relevance of these interactions remains an open question, and another function for KIR3DL2 as a receptor and transporter of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides has been proposed (77).

A possible consequence of rapidly co-evolving NK cell receptors and MHC ligands is the circumstance of NK cell receptors losing function, by failure to keep up with changes in MHC class I imposed by selected pressures from other functions, such as antigen presentation to CD8 T cells. Surviving such a crisis, with subsequent evolution of a new set of variable NK cell receptors could explain how humans and mice came to use completely unrelated proteins as variable NK cell receptors. The human KIR and mouse Ly49 became MHC class I receptors through convergent evolution, and being subject to similar selection pressure acquired several similar functional characteristics, including activating and inhibitor receptors with the same MHC class I specificity. The activating receptors have a greater tendency than their inhibitory counterparts to accumulate substitutions causing loss of receptor avidity (40, 78), a trend well illustrated by human activating lineage III KIR: 2DS1 has half the C2 avidity of 2DL1, 2DS4 binds weakly to just a few HLA class I allotypes, and 2DS2, 2DS3 and 2DS5 exhibit no binding to HLA class I.

Five of the substitutions we studied are principally found in activating KIR (threonine 44, lysine 70, arginine 71, tryptophan 131 and cysteine 182) and were therefore likely acquired through mutation of the activating KIR, and not from the inhibitory KIR from which they were formed by recombinations (78). When introduced into KIR2DL1 and KIR2DL3 these residues had no effect upon receptor specificity, but they all reduced avidity for HLA-C: KIR2DL1 avidity for C2 was reduced by 38-66% (mean of 51%), and KIR2DL3 avidity for C1 was reduced by 65-90% (mean of 74%). That positions 44, 70, 71, 131, and 182 were subject to positive selection implies there was functional advantage to reducing the potency of activating receptors with the introduction of threonine 44, lysine 70, arginine 71, tryptophan 131 and cysteine 182. Exemplifying this phenomenon is KIR2DS1*002 (the common 2DS1 allele) in which lysine substituted for threonine 70 was responsible for reducing C2 avidity to half that of KIR2DL1*003 (40, 79). At an early stage of pregnancy interplay and balance between KIR2DL1 and KIR2DS1 appears to modulate interactions between fetal trophoblast and maternal uterine NK cells that facilitate placentation. In pregnancies where the fetus expresses C2, the risk of preeclampsia and other disorders is less if the mother has both KIR2DL1 and KIR2DS1, than if she has only KIR2DL1 (80). If this balance was improved by having an activating receptor less avid than its inhibitory partner, it could explain the positive selection of lysine 70 in KIR2DS1.

Within the groups of C1-bearing and C2-bearing HLA-C there is a considerable and reproducible range of avidity for the cognate KIR. Because the observed binding is stable to washing and residues 7 and 8 of HLA-C bound peptide contact KIR (27, 56, 75), we suspect that the observed avidity differences are the consequence of substitutions in the peptide-binding site causing different populations of peptides to be bound by the various HLA-C allotypes. In this context, the selective and almost complete loss of binding to HLA-C*04:01 by mutant 2DL1-71P is a striking example of the increasing number of allotype-specific effects that are being uncovered in the study of HLA-C binding to lineage III KIR. This result is not an artifact of the direct binding assay, because 2DL1-71P on NK cell surfaces similarly fails to engage HLA-C*04:01 on target cells. In many studies of KIR specificity, HLA-C*04:01 and HLA-C*03:04 have provided the representative C2 and C1 epitopes, respectively (22, 23, 63, 81). Notably, these allotypes formed the complexes with KIR that were used to determine the three-dimensional structures (56, 75). Although a good ligand for KIR2DL1 in cellular assays of NK cell function, we have noticed that the binding of KIR2DL1 to HLA-C*04:01 is generally lower than for other C2-bearing allotypes. Such observations suggested HLA-C*04:01 could have some properties that are not representative of other C2-bearing HLA-C, a possibility that is strengthened by the results we report here.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI22039 (P.P.) and Telethon Foundation Grant GGP08201 (K.F.). H.H. was also supported by the March of Dimes Prematurity Center at Stanford University School of Medicine, CTSA grant (UL1 RR025744) and the Stanford University Dean’s Fellowship

References

- 1.Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cells. Blood. 2008;112:461–469. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-077438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell KS, Purdy AK. Structure/function of human killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors: lessons from polymorphisms, evolution, crystal structures and mutations. Immunology. 2011;132:315–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03398.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lanier LL. NK cell receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:359–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moretta A, Bottino C, Vitale M, Pende D, Biassoni R, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Receptors for HLA class-I molecules in human natural killer cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:619–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braud VM, Allan DS, O’Callaghan CA, Soderstrom K, D’Andrea A, Ogg GS, Lazetic S, Young NT, Bell JI, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, McMichael AJ. HLA-E binds to natural killer cell receptors CD94/NKG2A, B and C. Nature. 1998;391:795–799. doi: 10.1038/35869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez-Villar JJ, Melero I, Navarro F, Carretero M, Bellon T, Llano M, Colonna M, Geraghty DE, Lopez-Botet M. The CD94/NKG2-A inhibitory receptor complex is involved in natural killer cell-mediated recognition of cells expressing HLA-G1. J Immunol. 1997;158:5736–5743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abi-Rached L, Moesta AK, Rajalingam R, Guethlein LA, Parham P. Human-specific evolution and adaptation led to major qualitative differences in the variable receptors of human and chimpanzee natural killer cells. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parham P, Norman PJ, Abi-Rached L, Guethlein LA. Human-specific evolution of killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor recognition of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367:800–811. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajagopalan S, Long EO. A human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-G-specific receptor expressed on all natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1093–1100. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ponte M, Cantoni C, Biassoni R, Tradori-Cappai A, Bentivoglio G, Vitale C, Bertone S, Moretta A, Moretta L, Mingari MC. Inhibitory receptors sensing HLA-G1 molecules in pregnancy: decidua-associated natural killer cells express LIR-1 and CD94/NKG2A and acquire p49, an HLA-G1-specific receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5674–5679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovats S, Main EK, Librach C, Stubblebine M, Fisher SJ, DeMars R. A class I antigen, HLA-G, expressed in human trophoblasts. Science. 1990;248:220–223. doi: 10.1126/science.2326636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guethlein LA, Older Aguilar AM, Abi-Rached L, Parham P. Evolution of killer cell Ig-like receptor (KIR) genes: definition of an orangutan KIR haplotype reveals expansion of lineage III KIR associated with the emergence of MHC-C. J Immunol. 2007;179:491–504. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Older Aguilar AM, Guethlein LA, Adams EJ, Abi-Rached L, Moesta AK, Parham P. Coevolution of killer cell Ig-like receptors with HLA-C to become the major variable regulators of human NK cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:4238–4251. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Older Aguilar AM, Guethlein LA, Hermes M, Walter L, Parham P. Rhesus macaque KIR bind human MHC class I with broad specificity and recognize HLA-C more effectively than HLA-A and HLA-B. Immunogenetics. 2011;63:577–585. doi: 10.1007/s00251-011-0535-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandelboim O, Reyburn HT, Vales-Gomez M, Pazmany L, Colonna M, Borsellino G, Strominger JL. Protection from lysis by natural killer cells of group 1 and 2 specificity is mediated by residue 80 in human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen C alleles and also occurs with empty major histocompatibility complex molecules. J Exp Med. 1996;184:913–922. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizuki N, Ando H, Kimura M, Ohno S, Miyata S, Yamazaki M, Tashiro H, Watanabe K, Ono A, Taguchi S, Sugawara C, Fukuzumi Y, Okumura K, Goto K, Ishihara M, Nakamura S, Yonemoto J, Kikuti YY, Shiina T, Chen L, Ando A, Ikemura T, Inoko H. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the HLA class I region spanning the 237-kb segment around the HLA-B and -C genes. Genomics. 1997;42:55–66. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King A, Burrows TD, Hiby SE, Bowen JM, Joseph S, Verma S, Lim PB, Gardner L, Le Bouteiller P, Ziegler A, Uchanska-Ziegler B, Loke YW. Surface expression of HLA-C antigen by human extravillous trophoblast. Placenta. 2000;21:376–387. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King A, Boocock C, Sharkey AM, Gardner L, Beretta A, Siccardi AG, Loke YW. Evidence for the expression of HLAA-C class I mRNA and protein by human first trimester trophoblast. J Immunol. 1996;156:2068–2076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colonna M, Borsellino G, Falco M, Ferrara GB, Strominger JL. HLA-C is the inhibitory ligand that determines dominant resistance to lysis by NK1- and NK2-specific natural killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:12000–12004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.12000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colonna M, Spies T, Strominger JL, Ciccone E, Moretta A, Moretta L, Pende D, Viale O. Alloantigen recognition by two human natural killer cell clones is associated with HLA-C or a closely linked gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:7983–7985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.7983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moesta AK, Norman PJ, Yawata M, Yawata N, Gleimer M, Parham P. Synergistic polymorphism at two positions distal to the ligand-binding site makes KIR2DL2 a stronger receptor for HLA-C than KIR2DL3. J Immunol. 2008;180:3969–3979. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winter CC, Gumperz JE, Parham P, Long EO, Wagtmann N. Direct binding and functional transfer of NK cell inhibitory receptors reveal novel patterns of HLA-C allotype recognition. J Immunol. 1998;161:571–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winter CC, Long EO. A single amino acid in the p58 killer cell inhibitory receptor controls the ability of natural killer cells to discriminate between the two groups of HLA-C allotypes. J Immunol. 1997;158:4026–4028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moffett A, Loke C. Immunology of placentation in eutherian mammals. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:584–594. doi: 10.1038/nri1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valiante NM, Uhrberg M, Shilling HG, Lienert-Weidenbach K, Arnett KL, D’Andrea A, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, Parham P. Functionally and structurally distinct NK cell receptor repertoires in the peripheral blood of two human donors. Immunity. 1997;7:739–751. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Velardi A, Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, Aversa F, Christiansen FT. Natural killer cell allorecognition of missing self in allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation: a tool for immunotherapy of leukemia. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:525–530. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansasuta P, Dong T, Thananchai H, Weekes M, Willberg C, Aldemir H, Rowland-Jones S, Braud VM. Recognition of HLA-A3 and HLA-A11 by KIR3DL2 is peptide-specific. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1673–1679. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dohring C, Scheidegger D, Samaridis J, Cella M, Colonna M. A human killer inhibitory receptor specific for HLA-A. J Immunol. 1996;156:3098–3101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cella M, Longo A, Ferrara GB, Strominger JL, Colonna M. NK3-specific natural killer cells are selectively inhibited by Bw4-positive HLA alleles with isoleucine 80. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1235–1242. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gumperz JE, Litwin V, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, Parham P. The Bw4 public epitope of HLA-B molecules confers reactivity with natural killer cell clones that express NKB1, a putative HLA receptor. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1133–1144. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajalingam R, Parham P, Abi-Rached L. Domain shuffling has been the main mechanism forming new hominoid killer cell Ig-like receptors. J Immunol. 2004;172:356–369. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palacios C, Cuervo LC, Cadavid LF. Evolutionary patterns of killer cell Ig-like receptor genes in Old World monkeys. Gene. 474:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook JG, Bashirova A, Palmer S, Sims S, Trowsdale J, Abi-Rached L, Parham P, Carrington M, Beck S. Single haplotype analysis demonstrates rapid evolution of the killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) loci in primates. Genome Res. 2005;15:25–35. doi: 10.1101/gr.2381205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blokhuis JH, van der Wiel MK, Doxiadis GG, Bontrop RE. The mosaic of KIR haplotypes in rhesus macaques. Immunogenetics. 62:295–306. doi: 10.1007/s00251-010-0434-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.LaBonte ML, Hershberger KL, Korber B, Letvin NL. The KIR and CD94/NKG2 families of molecules in the rhesus monkey. Immunol Rev. 2001;183:25–40. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1830103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kruse PH, Rosner C, Walter L. Characterization of rhesus macaque KIR genotypes and haplotypes. Immunogenetics. 62:281–293. doi: 10.1007/s00251-010-0433-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hershberger KL, Kurian J, Korber BT, Letvin NL. Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) of the African-origin sabaeus monkey: evidence for recombination events in the evolution of KIR. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:922–935. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Older Aguilar AM, Guethlein LA, Adams EJ, Abi-Rached L, Moesta AK, Parham P. Coevolution of killer cell Ig-like receptors with HLA-C to become the major variable regulators of human NK cells. J Immunol. 185:4238–4251. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moesta AK, Abi-Rached L, Norman PJ, Parham P. Chimpanzees use more varied receptors and ligands than humans for inhibitory killer cell Ig-like receptor recognition of the MHC-C1 and MHC-C2 epitopes. J Immunol. 2009;182:3628–3637. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moesta AK, Graef T, Abi-Rached L, Older Aguilar AM, Guethlein LA, Parham P. Humans differ from other hominids in lacking an activating NK cell receptor that recognizes the C1 epitope of MHC class I. J Immunol. 2011;185:4233–4237. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyington JC, Motyka SA, Schuck P, Brooks AG, Sun PD. Crystal structure of an NK cell immunoglobulin-like receptor in complex with its class I MHC ligand. Nature. 2000;405:537–543. doi: 10.1038/35014520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robertson MJ, Cochran KJ, Cameron C, Le JM, Tantravahi R, Ritz J. Characterization of a cell line, NKL, derived from an aggressive human natural killer cell leukemia. Exp Hematol. 1996;24:406–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graef T, Moesta AK, Norman PJ, Abi-Rached L, Vago L, Older Aguilar AM, Gleimer M, Hammond JA, Guethlein LA, Bushnell DA, Robinson PJ, Parham P. KIR2DS4 is a product of gene conversion with KIR3DL2 that introduced specificity for HLA-A*11 while diminishing avidity for HLA-C. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2557–2572. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michaelsson J, Teixeira de Matos C, Achour A, Lanier LL, Karre K, Soderstrom K. A signal peptide derived from hsp60 binds HLA-E and interferes with CD94/NKG2A recognition. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1403–1414. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cerundolo V, Alexander J, Anderson K, Lamb C, Cresswell P, McMichael A, Gotch F, Townsend A. Presentation of viral antigen controlled by a gene in the major histocompatibility complex. Nature. 1990;345:449–452. doi: 10.1038/345449a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marsh SG, Albert ED, Bodmer WF, Bontrop RE, Dupont B, Erlich HA, Fernandez-Vina M, Geraghty DE, Holdsworth R, Hurley CK, Lau M, Lee KW, Mach B, Maiers M, Mayr WR, Muller CR, Parham P, Petersdorf EW, Sasazuki T, Strominger JL, Svejgaard A, Terasaki PI, Tiercy JM, Trowsdale J. Nomenclature for factors of the HLA system, 2010. Tissue Antigens. 2010;75:291–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2010.01466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winter CC, Long EO. Binding of soluble KIR-Fc fusion proteins to HLA class I. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;121:239–250. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-044-6:239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dukkipati A, Vaclavikova J, Waghray D, Garcia KC. In vitro reconstitution and preparative purification of complexes between the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and its ligands SDF-1alpha, gp120-CD4 and AMD3100. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;50:203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pei R, Lee JH, Shih NJ, Chen M, Terasaki PI. Single human leukocyte antigen flow cytometry beads for accurate identification of human leukocyte antigen antibody specificities. Transplantation. 2003;75:43–49. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200301150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.El-Awar N, Lee J, Terasaki PI. HLA antibody identification with single antigen beads compared to conventional methods. Hum Immunol. 2005;66:989–997. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barnstable CJ, Bodmer WF, Brown G, Galfre G, Milstein C, Williams AF, Ziegler A. Production of monoclonal antibodies to group A erythrocytes, HLA and other human cell surface antigens-new tools for genetic analysis. Cell. 1978;14:9–20. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brodsky FM, Bodmer WF, Parham P. Characterization of a monoclonal anti-beta 2-microglobulin antibody and its use in the genetic and biochemical analysis of major histocompatibility antigens. Eur J Immunol. 1979;9:536–545. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830090709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parham P, Androlewicz MJ, Holmes NJ, Rothenberg BE. Arginine 45 is a major part of the antigenic determinant of human beta 2-microglobulin recognized by mouse monoclonal antibody BBM.1. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:6179–6186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brodsky FM, Parham P. Evolution of HLA antigenic determinants: species cross-reactions of monoclonal antibodies. Immunogenetics. 1982;15:151–166. doi: 10.1007/BF00621948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brodsky FM, Parham P. Monomorphic anti-HLA-A,B,C monoclonal antibodies detecting molecular subunits and combinatorial determinants. J Immunol. 1982;128:129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fan QR, Long EO, Wiley DC. Crystal structure of the human natural killer cell inhibitory receptor KIR2DL1-HLA-Cw4 complex. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:452–460. doi: 10.1038/87766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Older Aguilar AM, Guethlein LA, Abi-Rached L, Parham P. Natural variation at position 45 in the D1 domain of lineage III killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) has major effects on the avidity and specificity for MHC class I. Immunogenetics. 2011;63:543–547. doi: 10.1007/s00251-011-0527-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barber LD, Percival L, Valiante NM, Chen L, Lee C, Gumperz JE, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, Bigge JC, Parekh RB, Parham P. The inter-locus recombinant HLA-B*4601 has high selectivity in peptide binding and functions characteristic of HLA-C. J Exp Med. 1996;184:735–740. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boyington JC, Sun PD. A structural perspective on MHC class I recognition by killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors. Mol Immunol. 2002;38:1007–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Della Chiesa M, Romeo E, Falco M, Balsamo M, Augugliaro R, Moretta L, Bottino C, Moretta A, Vitale M. Evidence that the KIR2DS5 gene codes for a surface receptor triggering natural killer cell function. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2284–2289. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.VandenBussche CJ, Mulrooney TJ, Frazier WR, Dakshanamurthy S, Hurley CK. Dramatically reduced surface expression of NK cell receptor KIR2DS3 is attributed to multiple residues throughout the molecule. Genes Immun. 2009;10:162–173. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moesta AK, Abi-Rached L, Norman PJ, Parham P. Chimpanzees use more varied receptors and ligands than humans for inhibitory killer cell Ig-like receptor recognition of the MHC-C1 and MHC-C2 epitopes. J Immunol. 2009;182:3628–3637. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wagtmann N, Rajagopalan S, Winter CC, Peruzzi M, Long EO. Killer cell inhibitory receptors specific for HLA-C and HLA-B identified by direct binding and by functional transfer. Immunity. 1995;3:801–809. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pende D, Biassoni R, Cantoni C, Verdiani S, Falco M, di Donato C, Accame L, Bottino C, Moretta A, Moretta L. The natural killer cell receptor specific for HLA-A allotypes: a novel member of the p58/p70 family of inhibitory receptors that is characterized by three immunoglobulin-like domains and is expressed as a 140-kD disulphide-linked dimer. J Exp Med. 1996;184:505–518. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Andersson S, Fauriat C, Malmberg JA, Ljunggren HG, Malmberg KJ. KIR acquisition probabilities are independent of self-HLA class I ligands and increase with cellular KIR expression. Blood. 2009;114:95–104. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yawata M, Yawata N, Draghi M, Partheniou F, Little AM, Parham P. MHC class I-specific inhibitory receptors and their ligands structure diverse human NK-cell repertoires toward a balance of missing self-response. Blood. 2008;112:2369–2380. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Colonna M, Navarro F, Bellon T, Llano M, Garcia P, Samaridis J, Angman L, Cella M, Lopez-Botet M. A common inhibitory receptor for major histocompatibility complex class I molecules on human lymphoid and myelomonocytic cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1809–1818. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.11.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fanger NA, Cosman D, Peterson L, Braddy SC, Maliszewski CR, Borges L. The MHC class I binding proteins LIR-1 and LIR-2 inhibit Fc receptor-mediated signaling in monocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3423–3434. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199811)28:11<3423::AID-IMMU3423>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jones DC, Kosmoliaptsis V, Apps R, Lapaque N, Smith I, Kono A, Chang C, Boyle LH, Taylor CJ, Trowsdale J, Allen RL. HLA class I allelic sequence and conformation regulate leukocyte Ig-like receptor binding. J Immunol. 2011;186:2990–2997. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shiroishi M, Tsumoto K, Amano K, Shirakihara Y, Colonna M, Braud VM, Allan DS, Makadzange A, Rowland-Jones S, Willcox B, Jones EY, van der Merwe PA, Kumagai I, Maenaka K. Human inhibitory receptors Ig-like transcript 2 (ILT2) and ILT4 compete with CD8 for MHC class I binding and bind preferentially to HLA-G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8856–8861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1431057100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Willcox BE, Thomas LM, Bjorkman PJ. Crystal structure of HLA-A2 bound to LIR-1, a host and viral major histocompatibility complex receptor. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:913–919. doi: 10.1038/ni961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dohring C, Scheidegger D, Samaridis J, Cella M, Colonna M. A human killer inhibitory receptor specific for HLA-A. J Immunol. 1996;156:3098–3101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hansasuta P, Dong T, Thananchai H, Weekes M, Willberg C, Aldemir H, Rowland-Jones S, Braud VM. Recognition of HLA-A3 and HLA-A11 by KIR3DL2 is peptide-specific. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1673–1679. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pende D, Biassoni R, Cantoni C, Verdiani S, Falco M, di Donato C, Accame L, Bottino C, Moretta A, Moretta L. The natural killer cell receptor specific for HLA-A allotypes: a novel member of the p58/p70 family of inhibitory receptors that is characterized by three immunoglobulin-like domains and is expressed as a 140-kD disulphide-linked dimer. J Exp Med. 1996;184:505–518. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boyington JC, Brooks AG, Sun PD. Structure of killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors and their recognition of the class I MHC molecules. Immunol Rev. 2001;181:66–78. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1810105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gonzalez-Galarza FF, Christmas S, Middleton D, Jones AR. Allele frequency net: a database and online repository for immune gene frequencies in worldwide populations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D913–919. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sivori S, Falco M, Carlomagno S, Romeo E, Soldani C, Bensussan A, Viola A, Moretta L, Moretta A. A novel KIR-associated function: evidence that CpG DNA uptake and shuttling to early endosomes is mediated by KIR3DL2. Blood. 2010;116:1637–1647. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-256586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abi-Rached L, Parham P. Natural selection drives recurrent formation of activating killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor and Ly49 from inhibitory homologues. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1319–1332. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Biassoni R, Pessino A, Malaspina A, Cantoni C, Bottino C, Sivori S, Moretta L, Moretta A. Role of amino acid position 70 in the binding affinity of p50.1 and p58.1 receptors for HLA-Cw4 molecules. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:3095–3099. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hiby SE, Apps R, Sharkey AM, Farrell LE, Gardner L, Mulder A, Claas FH, Walker JJ, Redman CW, Morgan L, Tower C, Regan L, Moore GE, Carrington M, Moffett A. Maternal activating KIRs protect against human reproductive failure mediated by fetal HLA-C2. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4102–4110. doi: 10.1172/JCI43998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Litwin V, Gumperz J, Parham P, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. NKB1: a natural killer cell receptor involved in the recognition of polymorphic HLA-B molecules. J Exp Med. 1994;180:537–543. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]