Abstract

Background

Data on long-term complications in adult patients with congenital heart disease (ACHD) and a prosthetic valve are scarce. Moreover, the influence of prosthetic valves on quality of life (QoL) and functional outcome in ACHD patients with prosthetic valves has not been studied.

Objectives

The primary objective of the PROSTAVA study is to investigate the relation between prosthetic valve characteristics (type, size and location) and functional outcome as well as QoL in ACHD patients. The secondary objectives are to investigate the prevalence and predictors of prosthesis-related complications including prosthesis-patient mismatch.

Methods

The PROSTAVA study, a multicentre cross-sectional observational study, will include approximately 550 ACHD patients with prosthetic valves. Primary outcome measures are maximum oxygen uptake during cardiopulmonary exercise testing and QoL. Secondary outcomes are the prevalence and incidence of valve-related complications including prosthesis-patient mismatch. Other evaluations are medical history, physical examination, echocardiography, MRI, rhythm monitoring and laboratory evaluation (including NT-proBNP).

Implications

Identification of the relation between prosthetic valve characteristics in ACHD patients on one hand and functional outcome, QoL, the prevalence and predictors of prosthesis-related complications on the other hand may influence the choice of valve prosthesis, the indication for more extensive surgery and the indication for re-operation.

Keywords: Congenital heart disease, Prosthesis-patient mismatch, Prosthetic heart valve, Valvular heart disease, Functional outcome, Quality of life

Background

Due to the improved survival of children with congenital heart disease (CHD), the number of adults with CHD has increased and adult patients with CHD now outnumber children [1]. Prosthetic valves, mechanical or biological, are part of the treatment in many patients with CHD. Mechanical prosthetic valves may negatively influence quality of life because of the necessity for anticoagulation therapy, which can hamper the active lifestyle of young adult patients with CHD and which prevents women from going through untroubled and safe pregnancies [2]. Biological prosthetic valves are an alternative, but they have their own disadvantages, the most important of which is their high deterioration rate, especially in young patients and during pregnancy, inevitably leading to re-operation [3].

Both types of valves share another complication: prosthesis-patient mismatch (PPM). PPM is present when the effective orifice area (EOA) of the inserted prosthetic valve is too small in relation to body size. In adults with acquired heart disease, PPM is associated with increased morbidity and mortality [4]. The prevalence of PPM is probably high in adult patients with CHD, both with biological and with mechanical valves, because of somatic growth of patients after implantation of a small valve during childhood. A few small series have investigated mid- and long-term complications of prosthetic valves including PPM in children [5, 6]. However, the prevalence of PPM and its consequences in adult patients with CHD are unknown.

Adult patients with CHD and a prosthetic valve differ from patients with acquired valve disease in terms of age, lifestyle and underlying disease. Additionally, the prevalence of tricuspid and pulmonary prosthetic valves is higher in adult patients with CHD. These differences may lead to a different outcome in terms of functional capacity and quality of life as well as to a distinct spectrum of long-term complications associated with prosthetic valves.

However, the influence of prosthetic valves on quality of life and functional outcome in adult patients with CHD has not been studied, and data on long-term complications are scarce [7]. We intend to study these issues in an adult population with CHD and prosthetic valves. In this article we introduce the study design and describe the rationale of the ‘Functional outcome and quality of life in adult patients with congenital heart disease and prosthetic valves (PROSTAVA) study’.

Methods

Study objectives

The primary objective of this multicentre cross-sectional observational study is to investigate the relationship between characteristics of valve prostheses (type, size, location) and functional outcome as well as quality of life in adult patients with CHD (objective 1). The secondary objectives of this study are to investigate the prevalence and predictors of PPM (objective 2) and the incidence of prosthesis-related complications (objective 3) in an adult CHD population.

Study population

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for objectives 1, 2 and 3 are shown in Table 1. All patients in the Dutch national CONCOR (‘CONgenital CORvitia’) database with valve prostheses (homografts, heterografts and mechanical valves) are eligible to participate in this study. Of the 900 identified patients, 702 were eligible for prospective investigation; by 15 February 2012, 406 of these patients with 424 valves were included in the PROSTAVA study (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria PROSTAVA

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| All objectives | All objectives |

| Included in the CONCOR database | Patient aged < 18 years |

| Prosthetic valve | |

| Objectives 1, 2 | Objective 1, 2 |

| Patients able to understand the study procedures | Pregnant or <3 months after pregnancy |

| Patients willing to provide informed consent | Inability to complete QoL questionnaire |

| Inability to perform cardiopulmonary aerobic capacity testing |

CONCOR CONgenital CORvitia; QoL quality of life

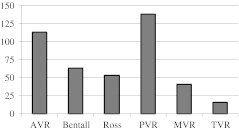

Fig. 1.

Prosthetic valves included in the prospective part of the study by 15 February 2012. AVR = aortic valve replacement, PVR = pulmonary valve replacement, MVR = mitral valve replacement, TVR = tricuspid valve replacement

Main procedures

Objective 1

Characteristics of valve prostheses (type, size and location) will be obtained from the medical records and from echocardiographic examination. For the evaluation of functional outcome and quality of life, cardiopulmonary aerobic capacity testing (CACT), New York Heart Association functional class and the SF-36 quality of life questionnaire will be used as primary outcome measures. Confounders which may influence the quality of life and functional outcome, such as ventricular function, native valve dysfunction and rhythm disorders, will be recorded using echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and 24-hour Holter recording.

Objective 2

To investigate the prevalence and degree of PPM, echocardiography will be used to measure the EOA and calculate the indexed EOA (iEOA = EOA/Body Surface Area). Consequences of PPM including the presence and degree of ventricular hypertrophy, ventricular and atrial volumes, and pulmonary pressures will be measured with MRI and/or echocardiography. Possible predictors of PPM will be identified from the medical records, such as underlying heart disease, type of cardiac surgery, type and size of valve prosthesis and age at implantation.

Objective 3

The inventory of the patient’s past medical history and present medical status (including current medical history and physical examination) will be used to record the incidence of prosthesis-related complications. Published guidelines will be used for the registration of complications [8]. To ensure completeness of data collection a patient interview will be used to check if any data were missed by studying the medical files; however, data that can not be verified from medical files are not qualified for entry in the database.

Laboratory evaluations will be performed to obtain information on heart failure and haemolysis. To detect rhythm disorders, ventricular hypertrophy and intraventricular conduction delays, electrocardiogram and 24-hour Holter monitoring will be used. Ventricular volumes, mass and function and prosthetic valve function will be assessed using echocardiography and MRI.

Cardiopulmonary aerobic capacity testing

The parameters to be recorded are: expected and achieved VO2max, respiratory quotient, anaerobic threshold, blood pressure at rest and during exercise, and heart rate at rest and during exercise.

Quality of life questionnaire

Quality of life will be assessed using the short-form 36 health survey questionnaire. This questionnaire consists of 36 items to measure health and quality of life using a multi-item scale for eight different aspects: physical functioning, role of limitations due to physical problems, role of limitations due to emotional problems, social functioning, mental health, pain, energy/vitality and general health. Furthermore, there is a single item on changes in respondents’ health over the past year.

Echocardiography

Two-dimensional echocardiography will be performed according to current guidelines to assess the function of prosthetic and native valves, to quantify chamber dimensions and left ventricular mass, and to assess chamber function. Pulmonary artery systolic pressure will be estimated and disease-specific evaluation performed. The EOA will be determined by the continuity equation using continuous and pulsed wave Doppler. For prosthetic valves, moderate PPM in the aortic and pulmonary valve position is defined as an iEOA of 0.65–0.85 cm2/m2 and severe PPM as iEOA ≤ 0.65 cm2/m2. For the mitral and tricuspid position, we will consider moderate PPM to be present when the iEOA is ≤ 1.25 cm2/m2 and severe PPM when the iEOA is ≤ 0.95 cm2/m2 [9, 10].

Magnetic resonance imaging

Systemic and pulmonary ventricular function, volume and mass will be determined with a steady-state free precession cine sequence in the short-axis plane. Flow dynamics, including the regurgitation fraction of the aortic and pulmonary valve, will be assessed by using velocity-encoded MR imaging distal to the prosthetic valve. It is expected that approximately 25 % of the patients will have a contraindication for MRI (i.e. pacemaker).

Statistical and ethical considerations

Sample size

Because this is an explorative study in a population where the prevalence of both valve characteristics (e.g. PPM) and the values for outcome measures are yet unknown, an appropriate sample calculation is not possible. However, the populations we expect to include are sufficiently large for all valve locations; therefore, meaningful outcomes can be expected.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables will be expressed as mean and standard deviation when normally distributed or as median with interquartile ranges in case of non-normal distribution. Categorical variables will be presented as absolute numbers and percentages.

Groups will be compared by using independent Student’s t-test for normally distributed continuous variables. Mann–Whitney U test will be used for comparisons of non-normally distributed continuous variables, and χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for comparison of categorical variables. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis will be performed to identify independent predictors for main outcome measures. All statistical analyses will be performed using the statistical software package SPSS version 16.0 or higher (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). All statistical tests are two-tailed and a P-value of < .05 is considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The PROSTAVA study has been approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of all the participating hospitals (METc2009/270; NL29965.042.09). The study will be conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Subjects will be asked to participate and sign a written informed consent form after having received written as well as oral information about the study.

Discussion

In the proposed PROSTAVA study, we will assess the implications of prosthetic valves in adult patients with CHD. We will have the opportunity to relate prosthetic valve characteristics to functional outcome and quality of life in a unique large-scale patient cohort. In addition we will investigate the incidence of complications related to prosthetic valve type, size and location in this adult population with CHD.

Valve type: biological or mechanical valve prosthesis

In children and young adults, biological valves are often implanted to avoid the disadvantages of oral anticoagulation therapy. The rate of structural valve degeneration is, however, high at young age. Structural valve deterioration results in progressive prosthesis dysfunction which will impair functional capacity and which ultimately leads to valve replacement. The influence of the amount and prospect of re-operations on quality of life in patients with CHD has only been studied in a relatively small population and seems to be limited [11]. However, parameters reflecting functional status are associated with satisfaction with life and perceived health [12]. Therefore we expect that structural valve deterioration in adult patients with CHD will influence quality of life through its impact on functional outcome, which we will elucidate in the PROSTAVA study.

Structural valve deterioration and re-operations can be avoided by use of mechanical prostheses. The risk of thromboembolic complications warrants the need for anticoagulation therapy resulting in an increased risk of bleeding complications. The cumulative risk of bleeding complications during life may well be high in young adults with CHD because of their long life expectancy after valve replacement. The risk of bleeding complications may be increased by the active lifestyle of many young adult patients with CHD. Frequent international normalised ratio (INR) controls are needed with anticoagulant therapy and patients are prevented from participating in risky sports activities. Poor compliance with warfarin therapy, which is not uncommon in adolescents, can increase the risk of thromboembolic complications. Pregnancy in women with mechanical valves bears the risk of foetal loss and embryopathy when oral anticoagulants are continued throughout pregnancy, while substitution with heparin increases the risk of thromboembolic complications [13, 14]. Therefore, the impact of anticoagulation therapy is probably high in this young population. Our study will provide insight into the incidence and predictors of biological and mechanical prosthesis-related complications in adult patients with CHD as well as the consequences for quality of life and functional outcome.

Valve size: the impact of PPM

When valve replacement is necessary in childhood, implantation of an adult-sized prosthetic valve is often not possible. With somatic growth in children, the iEOA decreases steadily until they reach adulthood. Therefore we expect that in our study population the prevalence of PPM will be high.

A few small series have investigated PPM in children [15]. However, in adult patients with CHD the prevalence and consequences of PPM are unknown. In patients with acquired valve disease, aortic PPM is associated with less improvement in symptoms and exercise capacity, less regression of left ventricular hypertrophy, more cardiac events and higher mortality [4, 9, 16]. Mitral PPM is associated with recurrence of congestive heart failure, pulmonary hypertension and decreased survival [10]. We expect that PPM in adult patients with CHD will further diminish the already compromised ventricular function and exercise capacity. This reduction in exercise capacity may negatively influence quality of life by limiting these patients in their daily activities. Our study will provide a comprehensive database with a long follow-up to present us with useful information on the incidence, predictors and consequences of PPM in adult CHD patients.

Valve location: right-sided versus left-sided prostheses

Prevalence of tricuspid and pulmonary prosthetic valves is relatively high in adult patients with CHD compared with patients with acquired valve disease. In right-sided mechanical prostheses thromboembolic risk is presumed to be higher compared with left-sided mechanical prostheses due to lower pressures and flow velocities in the right heart. Therefore, biological valves are the preferred valve type in the tricuspid and pulmonary position in most centres. Several recent studies have reported satisfactory results in pulmonary mechanical prostheses with aggressive anticoagulation, INR 3.0–4.5 [17, 18]. However, data concerning long-term survival, and thromboembolic and bleeding complications are still limited. Available studies are small and the only large study with more than 30 patients has a short median follow-up of only 2 years. The proposed study gives the possibility to compare complications of pulmonary mechanical valves in a relatively large cohort (54 patients) and a cohort of patients with biological valves, with a long median follow-up duration of more than 6 years.

Limitations

A limitation of our study is the presence of multiple confounding factors such as the heterogeneity of patients with CHD, multiple types and locations of prosthetic valves and differences in ventricular function. Regression analysis will partially overcome this limitation. As patients who are not able to complete the CACT and quality of life questionnaire will be excluded from the prospective study, the study population will not be entirely representative for adult patients with CHD and a prosthetic valve.

Another limitation comes with the use of the CONCOR database. This database started including patients with CHD in 2001. Patients who died before this date are not included, which will limit the possibility to investigate long-term mortality.

Conclusion

The PROSTAVA study is the first study to investigate the influence of prosthetic valve characteristics on functional outcome and quality of life in adult congenital heart disease patients. Our results may influence the choice of valve prosthesis, the indication for more extensive surgery and the indication for re-operation in patients with prosthesis patient mismatch.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

This study is supported by a grant from the Netherlands Heart Foundation to P.G.P. (2009B013).

Footnotes

The questions can be answered after the article has been published in print. You have to log in to: www.cvoi.nl.

References

- 1.Marelli AJ, Mackie AS, Ionescu-Ittu R, et al. Congenital heart disease in the general population: changing prevalence and age distribution. Circulation. 2007;115:163–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.627224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drenthen W, Boersma E, Balci A, et al. Predictors of pregnancy complications in women with congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2124–32. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahimtoola SH. Choice of prosthetic heart valve in adults an update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2413–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tasca G, Mhagna Z, Perotti S, et al. Impact of prosthesis-patient mismatch on cardiac events and midterm mortality after aortic valve replacement in patients with pure aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2006;113:570–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.587022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karamlou T, Jang K, Williams WG, et al. Outcomes and associated risk factors for aortic valve replacement in 160 children: a competing-risks analysis. Circulation. 2005;112:3462–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.541649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masuda M, Kado H, Ando Y, et al. Intermediate-term results after the aortic valve replacement using bileaflet mechanical prosthetic valve in children. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:42–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oosterhof T, Meijboom FJ, Vliegen HW, et al. Long-term follow-up of homograft function after pulmonary valve replacement in patients with tetralogy of Fallot. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1478–84. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akins CW, Miller DC, Turina MI, et al. Guidelines for reporting mortality and morbidity after cardiac valve interventions. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:732–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pibarot P, Dumesnil JG. Hemodynamic and clinical impact of prosthesis-patient mismatch in the aortic valve position and its prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1131–41. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00859-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pibarot P, Dumesnil JG. Prosthesis-patient mismatch in the mitral position: old concept, new evidences. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:1405–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loup O, Weissenfluh C, Gahl B, et al. Quality of life of grown-up congenital heart disease patients after congenital cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;36:105–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moons P, Deyk K, Geest S, et al. Is the severity of congenital heart disease associated with the quality of life and perceived health of adult patients? Heart. 2005;91:1193–8. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.042234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pieper PG, Balci A, Dijk AP. Pregnancy in women with prosthetic heart valves. Neth Heart J. 2008;16:406–11. doi: 10.1007/BF03086187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pieper PG. Expected and unexpected cardiac problems during pregnancy. Neth Heart J. 2008;16:403–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03086186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masuda M, Kado H, Tatewaki H, et al. Late results after mitral valve replacement with bileaflet mechanical prosthesis in children: evaluation of prosthesis-patient mismatch. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:913–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tasca G, Brunelli F, Cirillo M, et al. Impact of valve prosthesis-patient mismatch on left ventricular mass regression following aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:505–10. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waterbolk TW, Hoendermis ES, Hamer IJ, et al. Pulmonary valve replacement with a mechanical prosthesis. Promising results of 28 procedures in patients with congenital heart disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.02.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stulak JM, Dearani JA, Burkhart HM, et al. The increasing use of mechanical pulmonary valve replacement over a 40-year period. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:2009–15. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]