SUMMARY

This study explores relationships between young adult restaurant employees' understanding and compliance with workplace alcohol control policies and consequences of alcohol policy violation. A mixed method analysis of 67 semi-structured interviews and 1,294 telephone surveys from restaurant chain employees found that alcohol policy details confused roughly a third of employees. Among current drinkers (n=1,093), multivariable linear regression analysis found that frequency of alcohol policy violation was positively associated with frequency of experiencing problems at work; perceived supervisor enforcement of alcohol policy was negatively associated with this outcome. Implications for preventing workplace alcohol-related problems include streamlining confusing alcohol policy guidelines.

Keywords: Workplace policy, alcohol use, young adults, food service workers

INTRODUCTION

Research on the correlates of work-related drinking has identified permissive drinking norms (Ames et al., 2007; Ames et al., 2000; Bacharach et al., 2002; Barrientos-Gutierrez et al., 2007; Delaney and Ames, 1995) and drinking networks at work (Janes and Ames, 1989) as key group influences on individual behavior. To counteract these influences, employers can provide the infrastructure to deal with alcohol related problems at work through employee assistance programs (Roman and Blum, 2002) as well as primary prevention policies regarding work-related alcohol and drug use (Ames et al., 2000; Pidd et al., 2006).

The literature on occupational prevention and employee assistance programs suggests that although there are multiple connections between leisure and work (e.g., Long Dilworth, 2004), substance misuse prevention policies tend to focus upon work performance as a key criterion rather than explicitly targeting off-the-clock behavior. Relevant workplace alcohol policies include those which address rules and regulations regarding drinking at work, on breaks, between shifts, coming to work under the influence of alcohol, including hangovers (Moore, 1998), and whether or not consequences concern treatment programs (Trice and Sonnenstuhl, 1988), and disciplinary action (Ames et al., 1992). More generally, and in addition to alcohol-specific policy, workplace policies concerned with job performance and attendance may help control work-related alcohol problems because of their relevance for heavy drinkers or smokers who take frequent breaks or call in sick more frequently (Ames et al., 2000).

The literature on occupational drinking norms and practices suggests that workplace rules concerning alcohol use before, during, and after work hours are most effective in reducing employee work-related drinking when they are clear and are consistently enforced (Ames and Delaney, 1992; Ames et al., 2000). Moreover, occupational alcohol research has found significant relationships between work-related drinking among assembly worker population and perceptions that alcohol policies are lax and unenforceable (Delaney and Ames, 1995; Grube et al., 1994).

Written workplace policies describing disciplinary consequences for alcohol and drug use constitute a potentially significant piece of a comprehensive occupational substance use prevention program. In the 2002–2004 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, 78.7% of full-time U.S. workers reported being aware of a written drug and alcohol policy at their place of employment (Larson et al., 2007). With relevance to young adults, self-reported illicit drug use was approximately 8% less frequent among workers between the ages of 18 and 25 who reported having a written policy at work than among their agemates who did not have a written workplace alcohol policy.

Nationwide surveys have found restaurant and other food service work among the occupations with the highest rates of heavy and problem drinking (Larson et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 1999). For example, the 2002–2004 National Household Surveys on Drug Use and Health found that 15.2% of waiters, bartenders and other workers in the food service industry reported past-month heavy alcohol use, and 19.6% of them reported past-year alcohol dependence or abuse (Larson et al., 2007).

The current study builds upon our previous work showing the high prevalence of problem drinking among young adult workers in a large national bar-restaurant chain (Moore et al., 2009), part of the $516 billion dollar commercial restaurant industry (National Restaurant Association, 2009). Specifically, we found that 41% of 1294 restaurant workers met gender-specific criteria for problem drinking based on the AUDIT, a screener developed by the World Health Organization that identifies those who have engaged in hazardous drinking resulting in increased risk of harm to self or others (Babor et al., 2001). The purpose of this paper is to explore young restaurant workers' understanding of workplace alcohol policy, as well as the consequences of alcohol policy violation, using qualitative and quantitative methods. This mixed methods approach allows us to use our ethnographic findings to explicate results from the quantitative survey analysis, thereby providing more holistic explanations for the occupational and drinking-related behaviors among the sample. Following the results, we provide policy recommendations for prevention of workplace alcohol-related problems.

METHODS

QUALITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS

To address questions about connections between alcohol policy comprehension and compliance and alcohol-related problems both at work and more generally, sixty-four face-to-face semi-structured interviews were held with service and kitchen staff in locations across the country. Interview instruments were developed to cover employee perceptions of rules concerning alcohol use at work and enforcement of rules, as well as their experience with customers, other restaurant employees, and managers. Respondents between the ages of 18 and 29 were chosen randomly from employee lists provided by seventeen restaurants in the Midwestern, Southern, and Northeastern U.S. divisions of a nationwide restaurant-bar chain. Urban, suburban, and rural restaurant locations were included in each region. These respondents included 19 bartenders, 12 servers, 13 kitchen workers, 8 hosts/hostesses, and 7 managers, evenly divided between 32 men and 32 women. An additional three interviews with managerial staff at the corporate headquarters provided particular insight into alcohol policy formulation.

The semi-structured qualitative interviews were carried out by three of the authors, who are experienced in on-site qualitative workplace research. Some of the interviews were conducted in Spanish. Incentive fees of $25 each were offered for participation in both the survey and qualitative interviews. All interviews were recorded and transcribed (and translated, when necessary) verbatim.

Using the qualitative text management software package ATLAS.ti (Muhr, 2006), the interview transcripts were coded by the research team for recurring themes or topics, including employees' understanding of alcohol control policy. A theme may be defined as a specific category or subcategory of information that appears throughout the interview data in similar or varying contexts and with interconnectedness to other themes (Ryan and Bernard, 2003). Themes may be directly or indirectly addressed by the majority of informants, or by a select few who, because of specific or differing characteristics (e.g., gender, ethnicity, job category or work setting), have different experiential realities.

The team's anthropologists developed the thematic coding manual after reading the first six interviews independently and then comparing and reaching consensus. Thereafter, they revised the manual by including sub-themes and new themes that emerged in the course of analyzing the interviews. This inclusion of both a priori codes and inductive codes follows guidelines laid down by Strauss and Corbin (1998). Conducting analyses related to workplace alcohol policy, the research team members retrieved coded segments of text concerning drinking behaviors, policy comprehension and enforcement, and examined other codes that were assigned to the same and adjacent blocks of text. Recurring themes connected to the relationship between policy and problem drinking behaviors were identified and are illustrated below.

SURVEY METHODS

The restaurant-bar chain provided the researchers with a roster of 4,999 employees between the ages of 18 to 29. Professionally trained interviewers attempted to contact by telephone all 4,999 employees. Excluding individuals who could not be reached because of non-working telephone numbers, 1,892 were found eligible to participate in the study. Of these, 339 (17.9%) refused to participate, 259 (13.7%) were deemed eligible but asked to be called later, and 1,294 were interviewed after providing informed consent, resulting in a 68.4% response rate (Moore et al, 2009).

SURVEY MEASURES

Problems at work (Outcome)

Questions concerning the frequency of problems experienced at work during the preceding year were derived from a scale created in our previous occupational studies (Ames et al., 1997). These work problems have been shown to correlate with heavy drinking. Items included 'had a heated argument with your supervisor', 'been in a physical fight with a co-worker', 'been in a heated argument with a co-worker', 'been hung over at work', 'called in sick', 'had an injury at work', 'been involved in an accident at work', 'been criticized by supervisor', and 'came to work late.' Respondents were asked to state the number of days each of these problems had occurred over the past 12 months. Responses to each of the 9 items were summed and divided by 9 to create a summary score of work problem frequency for each respondent.

Alcohol Policy Understanding

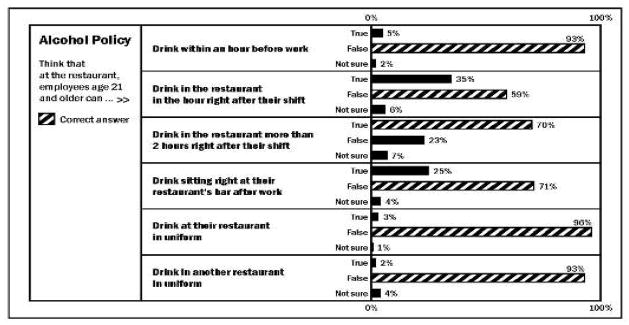

A series of true-false questions asked if specific drinking practices by employees over 21 (drinking within an hour before work, drinking in the restaurant in the hour right after their shift, drinking in the restaurant more than 2 hours right after their shift, drinking sitting right at their restaurant's bar after work, drinking at their restaurant in uniform and drinking in another of their chain's restaurants in uniform) was permitted by the restaurant's employee alcohol use policy.

Alcohol Policy Compliance

A series of questions then asked about the number of times during the past month the respondent had engaged in the specific drinking practices prohibited by the restaurant's employee alcohol use policy. These included drinking within an hour before work, drinking during work hours, drinking in the restaurant in the 2 hours right after their shift, drinking sitting right at their restaurant's bar, drinking in their restaurant in uniform, drinking at another of their chain's restaurants in uniform, and drinking more than 2 drinks at any time in their restaurant. Response categories ranged from 'not at all' to '5–6 days per week.' Responses to the items were summed to create an alcohol policy compliance score for each respondent.

Perception of Supervisors' Strict Enforcement of Alcohol Policy

Respondents were asked to rate on a five-point scale (1= very lenient to 5 = very strict) how strict or lenient their immediate supervisor was in enforcing the restaurant's rules about employee alcohol use. A variable was created for each respondent based on their perception.

Frequency of Intoxication

Respondents were asked, "During the past 12 months, about how often did you drink enough to feel intoxicated or drunk, that is, when your speech was slurred, you felt unsteady on your feet, or you had blurred vision? Response categories ranged from 'every day' to 'not at all.'

Smoking

Respondents who reported smoking any cigarettes in the past 30 days were classified as current smokers

Sociodemographic Factors

Gender

Participant gender was coded as male or female.

Age

Each respondent was asked how old they were at the time of the survey.

Race/ethnicity

Self-reported race/ethnicity was recorded for each respondent.

Education

Respondents were asked to state their highest level of completed education. They were also asked whether they were currently enrolled in school.

Occupational Factors

Job Categories

The self-reported job duties of respondents were classified as follows: those serving customers, including waiters, waitresses, and bartenders, were categorized as servers; those without direct customer contact, including cooks and dishwashers, were categorized as kitchen staff; and those assisting servers (e.g., busboys, and hosts) were categorized as hosts.

Work shifts

Workers were classified as working predominantly during the day shift, night shift, or no regular shifts.

ANALYTIC STRATEGY

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, proportions) were computed for continuous and categorical variables. Chi square tests of independence were used to test whether workplace alcohol policy comprehension (having none, 1, 2, or 3 or more incorrect responses on the survey's workplace alcohol policy questions) varied by age (18 to 20 years old; 21 to 24 years old; 25 to 29 years old). A multivariable linear regression model was developed to estimate the contribution of policy-related factors and frequency of intoxication to work-related problems. Control variables included gender, age, level of education, race/ethnicity, occupational category and shift. Smoking was included in the model as a potential confounder. This analysis was conducted among current drinkers only (86% of the sample) since, by definition, only drinkers could violate the company's workplace alcohol policies.

FINDINGS

QUALITATIVE RESULTS

Formulation and Dissemination of Policy

In the bar-restaurant chain described here, a written policy on alcohol use was introduced to workers during their orientation. At some restaurants, these policies were posted out of sight of the public. At the time of the survey, the elements of this policy were as follows: 1. Employees were not to drink alcohol within an hour before going to work, with the rationale that they were not to be impaired at work; 2. Employees were not to drink alcohol during work hours, with the exception of servers over the age of 21 who were permitted to taste small samples of new specialty drinks promoted by the organization (The idea behind this exception was to enable bartenders and servers to describe these drinks to their customers); 3. Employees were not to drink alcohol in their restaurant within the two hours following their shift; one rationale provided to us was to avoid negative perceptions from customers whom they might have served just before the end of the shift; 4. For similar reasons, employees were not to drink alcoholic beverages in uniform at any establishment; 5. Employees were not to drink alcohol sitting directly at their restaurant's bar; 6. Finally, employees were not to drink more than two alcoholic beverages while off-duty in their restaurant, if all other conditions (e.g., out of uniform, time elapsed after shift, not sitting at the bar and of course being at least 21 years of age) had been met.

Approximately five years prior to data collection, the restaurant chain's alcohol policy was modified from a simple agreement not to drink during work hours to the complex series of limitations described above. Although employees were never allowed to consume alcohol during work, other than to taste new drink specials, there was a growing concern among management about the potentially negative consequences of workers drinking in the restaurant after their shift was completed. These concerns were less about workers becoming intoxicated per se, than in being a distraction to workers who were still on the clock. As a general manager noted: "You've got your off-duty folks having drinks, you have your on-duty folks who are talking with them. Before you know it, somebody's doing something wrong and loses their job."

This same manager reported that trying to change the policy so that employees could not drink in their restaurant until at least two hours after their shift met with some resistance within the company. "The debate became an economic debate. We had people in marketing say, 'Look, that's sales dollars, they're a paying customer, so you're telling me they can't have drinks at our restaurant? We're shooing them over to a competitor.'" In the course of changing the policy regarding after-work drinking, the company also codified a number of additional policies regarding workers' drinking comportment, the elements of which are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Most workers learn about the company's alcohol policy during their job orientation, in which a manager verbally describes the rules, illustrating them with a tabletop flip chart. Moreover, workplace alcohol policy is contained in an employee manual. During their orientation, new hires are required to sign a statement asserting that they have read and understood the policy. Some restaurants we visited also posted the policy in the kitchen area, although this was relatively uncommon. When asked about whether employees find the policy to be confusing, a high-level manager in the corporate headquarters told us: "Well to me it's crystal clear. And I think that they're pretty solid when they deliver that message during the orientation." However, when we interviewed workers in sites across the country, we found that they were often confused about the company's alcohol policies, which could have negative consequences in terms of their drinking behaviors. Illustrating this confusion, one 20 year old hostess stated, "You know they run over it at orientation, and I believe the rule is you are allowed to go in for drinks, but you're not allowed to sit at the bar. But, other than that, I don't really remember because it's so long ago. But, again, I'm not legal to drink."

Confusion about policy details was not limited to underage employees. A female kitchen worker of legal drinking age actually thought the rules were more restrictive than they really were, but understood the underlying rationale articulated by headquarters management: "You can sit at the tables around the bar if you're not in uniform and if you have not been working for something like 3 or 4 hours or something like that. They don't want customers that were in the restaurant that you waited on to see you come in a half an hour later or even in a different uniform, coming in a half an hour later and sit at the bar and have a beer."

Worker confusion about alcohol policy details was particularly pronounced regarding the number of drinks that they were permitted to have in the restaurant if all other requirements were satisfied (being 21 or older, having completed work two hours earlier, not being in uniform, and not sitting right at the bar). However, over time it is likely that the details of the policy became unclear for some workers, particularly when the policies are posted solely in the employee handbook, where it is unlikely to be reread after orientation.

From the perspective of some employees, the policies were not as appealing as they were to the upper management. For example, a bartender and waiter spoke nostalgically of when employees could drink right after their shifts at the bar-restaurant, but had an interpretation for why the policy was stricter: "Someone got killed driving home after work and corporate nicked it right there. So, one person ruined it for the rest. But, I know this other place I used to work at you can drink after work, and I don't see a problem… I don't see a problem with it. I know if I owned a restaurant, I'd let you drink."

A female bartender said, "Well, I don't think the rules have changed over time. I think that they were bent over time. And you know, it was fine, everything was going well and probably something bad happened because the rules were getting bent so they got strict. Just like with anything, you know, let it go, let it go until something bad happens and then you go, 'Oh, wow the policy!'"

Alcohol policy enforcement

From a manager's perspective, having a clear alcohol policy made that policy easier to enforce. One restaurant manager said, "You can't rely on people to be able to monitor themselves, so they have to make some policy. It really makes our job easier as managers because there is a policy. And, if you stick with the policy, then you don't have problems with people that work for you or work for [the company] being drunk. Because any time [employees] are in here and they're not working, they get in the way of work. When they're drinking, it's even worse. It may become a distraction for everyone else that's working."

In terms of enforcement of these policies, most employees portrayed their managers as interpreting the policy guidelines fairly. A waiter recalled an incident in which a coworker came to work incapacitated with a hangover: "A girl came in and she was hung over. She was getting sick in the bathroom. They just told her to go home and don't do this again. She needed the money, I know she had bills to pay, but that was her choice, she did what she did. They just told her you can go ahead, but don't do this again. They are not necessarily like, 'You're fired because you came in with a hangover,' but they're strict about it."

When asked if enforcement of the alcohol control policy was overly strict in her restaurant, a hostess replied, "No. I think the way our managers take care of us and the restaurant is right on. I mean, they are not so strict that people take it as they're being rude, but they're not so lenient that people can get away with something. They take care of what needs to be taken care of." To illustrate an example of enforcement that sent a message to other employees, an underage host mentioned a waiter who was caught drinking, "He was like the number one server, he was really good and everything, and everybody liked him. He made more money than anybody else just because he was so good at his job. But, they caught him drinking right before he came into work and he actually got fired for that. So they told me you can't come in, smelling like alcohol."

In the qualitative portion of the study, some employees described lax enforcement of the policies, but most had the sense that the managers enforced the protocols outlined in the manual. They did not always agree on the details of those policies, however. Again and again, when asked about the details of the policy, non-managerial employees of all kinds described different numbers of hours without drinking required before or after work, and different numbers of drinks they were permitted to consume on the premises once they had changed out of their uniform, indicating that they had not retained the key points of the policy. The survey findings, reported below, shed more light on the relationships between policy comprehension and compliance on the one hand, and on the other, self-reported alcohol-related problems at work.

QUANTITATIVE RESULTS

Survey Sample Characteristics

Background Factors

Most respondents (58%) were female; 42% were male. On average, respondents were 22.3 years of age (SD 2.9). Nearly 48% reported being current smokers. Most sample respondents (59%) were currently enrolled in school. About 13% of respondents reported their race/ethnicity as African American, Hispanic, or other (non-white).

Occupational Factors

In terms of job categories, 11% were hosts, 64% were servers (including bartenders), and 25% worked in the kitchen. Regarding length of employment, most respondents had worked at the restaurant one year or less. Specifically, 29% had worked there less than 6 months; 27% had worked between 6–12 months, 33% between 1 and 3 years and 11% more than 3 years. Approximately 17% worked the day shift, 54% worked the night shift, 11% worked a split shift, and 18% reported no usual shift.

Policy violations and comprehension

A third (33.5%) of survey respondents who drank reported violating one or more elements of the employee alcohol policy in the past month. As Figure 1 indicates, a majority of employees understood basic elements of the policy such as refraining from drinking during work hours, but were confused about other policy details, including the number of hours after their shift that must elapse before they can drink at the restaurant.

Bivariate analysis showed that there were significant age differences (chi-square=34.18, 6df, p<.001) in the proportions of employees who correctly understood workplace alcohol policies, with employees 18–20 years old (n=471) reporting more errors than those 21–24 (n=536) or those 25–29 (n=283).

MULTIVARIATE RESULTS

Relationships between policy violations and work problems,

Table 1 presents the results of the linear regression model, which shows that frequency of past-month alcohol policy violations was significantly associated (beta = 0.084, p=0.005) with the outcome, work problems. Perceived alcohol policy enforcement on the part of one's supervisor was inversely associated with work problems (beta=-0.112, p < 0.001); in other words, the more that workers thought that their supervisor would enforce the policy, the less likely they were to violate it. Being a current smoker (beta=0.080, p = 0.007) and frequency of intoxication (beta=0.304, p < 0.001) were also significantly associated with experiencing work problems. Working the day shift compared to night shift was significantly correlated to work problems (beta=0.062, p < 0.05). Those who were classified as servers had a significantly negative correlation to work problems compared to those classified as kitchen workers (beta=−0.086), p = 0.02. Interestingly, the analysis showed that gender was not a significant correlate of work problems.

Table 1.

Standardized coefficients from linear regression model for frequency of work problems among young adult restaurant workers (current drinkers only, n=1093)

| Beta | t | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 3.010 | 0.003 | |

| Male | 0.034 | 1.067 | 0.286 |

| Current smoker | 0.080 | 2.698 | 0.007 |

| Age | −0.024 | −0.727 | 0.467 |

| Enrolled in school | 0.014 | 0.446 | 0.656 |

| High school education | −0.047 | −1.613 | 0.107 |

| Non-white race/ethnicity | 0.046 | 1.609 | 0.108 |

| Host | −0.048 | −1.344 | 0.179 |

| Server | −0.086 | −2.321 | 0.020 |

| Past month alcohol policy violation score | 0.084 | 2.807 | 0.005 |

| Frequency of intoxication | 0.304 | 10.335 | <0.001 |

| Perceived alcohol policy supervisor enforcement | −0.112 | −3.962 | <0.001 |

| Day shift | 0.062 | 2.112 | 0.035 |

| Split shift | −0.006 | −0.216 | 0.829 |

| No usual shift | −0.018 | −0.631 | 0.528 |

| R2 =0.169 |

The regression model shows that the more frequently these young workers report having been inebriated, the more work problems they will report. While we did not explicitly ask where employees drank, it is reasonable to assume that it was off-duty because little on-the-job drinking was reported in the survey. This finding was triangulated by the qualitative interviews in which close managerial oversight of employee behavior made drinking on the job untenable. Violations of alcohol policy were also significantly associated with frequency of work problems. Moreover, additional analysis using bivariate logistic regression (OR=1.44; 95% CI 1.29, 1.62; p< .001) showed that among current drinkers (85% of the sample), past-month alcohol policy violations were significantly associated with likelihood of being classified as a hazardous drinker (i.e., positive AUDIT score).

DISCUSSION

Both qualitative and quantitative analyses point to extensive employee confusion, particularly among workers under the legal drinking age of 21, about details of their employer's alcohol control policies, It is worth noting that among current drinkers, the survey analysis found that employees were more likely to be classified as hazardous drinkers when they violated the alcohol policy in the month prior to the survey.

The picture that emerges from these analyses is interesting and complex, namely: a) few workers drank at work; b) despite this, those who scored lower on the policy questions were more likely to drink heavily (presumably outside of work); c) those who drank more (again outside of work) were more likely to have problems at work, and; d) those who violated alcohol policies were more likely to have problems at work. These mixed-method findings suggest that overly complex alcohol guidelines may be difficult to follow or enforce in an occupation such as restaurant work, which is characterized by high turnover and a young adult work force.

Implications for prevention of alcohol-related problems at work include clarifying confusing policy guidelines and periodic review to ensure that employees fully understand their company's alcohol control policy, especially in light of the association between alcohol policy noncompliance with hazardous drinking, and alcohol-related problems at work. However, it is worth noting that in this population, hazardous drinking tends to occur outside the confines of work hours, and thus might be considered beyond the purview of a work policy, except for the case of hangovers or disruption of workers by their off-the-clock colleagues who drink in the establishment.

As with all studies relying upon cross-sectional survey data we were unable to establish causal relationships. Moreover, employees may have under-reported their substance use in the context of an occupational health survey, despite assurances of confidentiality. If this were the case, the results of the model may represent an attenuation of the association between variables such as frequency of intoxication and past-month violation of alcohol policy with the outcome, work problems. Strengths of this study include the use of mixed methods to shed additional light on the frequently stated observation in the literature that young adult hospitality industry workers are heavy drinkers (Leigh, 1995; Moore et al., 2009). This study's focus on policy elements that were added to the restaurant chain's guidelines for its workers indicates that specific steps may be taken to alter the workplace environment of these heavy drinkers. Thus these findings may inform prevention efforts targeting negative consequences of alcohol use among this population.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIAAA Grant #R01-AA015423 (Genevieve Ames, PI; Roland Moore, CoPI). We are thankful for the entrée and ongoing cooperation provided by the restaurant chain management and personnel, who have requested not to be named in our reports. We also would like to thank Michael Frone for his help in developing the survey instrument.

Contributor Information

Roland S. Moore, Email: roland@prev.org, Senior Research Scientist at the Prevention Research Center, Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation (PIRE), 1995 University Ave., Ste. 450, Berkeley, CA 94704-5315 USA.

Genevieve M. Ames, Senior Research Scientist and Associate Director of the Prevention Research Center, PIRE. She is also an Adjunct Professor in the University of California, Berkeley's School of Public Health.

Carol B. Cunradi, Senior Research Scientist at the Prevention Research Center, PIRE.

Michael R. Duke, Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology, University of Memphis.

References

- Ames GM, Cunradi CB, Moore RS, Stern P. Military culture and drinking behavior among U.S. Navy careerists. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(3):336–344. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames GM, Delaney WP. Minimization of workplace alcohol problems: The supervisor's role. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1992;16(2):180–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb01362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames GM, Delaney WP, Janes CR. Obstacles to effective alcohol policy in the workplace: A case study. British Journal of Addictions. 1992;87:1055–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb03124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames GM, Grube JW, Moore RS. The relationship of drinking and hangovers to workplace problems: an empirical study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58(1):37–47. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames GM, Grube JW, Moore RS. Social control and workplace drinking norms: A comparison of two organizational cultures. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61(2):203–219. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. 2. Geneva: World Health Organization Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bacharach SB, Bamberger PA, Sonnenstuhl WJ. Driven to drink: Work-related risk factors and employee problem drinking. Academy of Management Journal. 2002;45:637–658. [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos-Gutierrez T, Gimeno D, Mangione T, Harrist R, Amick B. Drinking social norms and drinking behaviours: A multilevel analysis of 137 workgroups in 16 worksites. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2007;64:602–608. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.031765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney WP, Ames GM. Work team attitudes, drinking norms, and workplace drinking. Journal of Drug Issues. 1995;25(2):275–290. [Google Scholar]

- Grube JW, Ames GM, Delaney WP. Alcohol expectancies and workplace drinking. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1994;24(7):646–660. [Google Scholar]

- Janes CR, Ames GM. Men, blue collar work and drinking: alcohol use in an industrial subculture. Culture Medicine and Psychiatry. 1989;13(3):245–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00054338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson SL, Eyerman J, Foster MS, Gfroerer JC. Worker Substance Use and Workplace Policies and Programs (DHHS Publication No SMA 07-4273, Analytic Series A-29) Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh JP. Dangerous jobs and heavy alcohol use in two national probability samples. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1995;30:71–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long Dilworth J. Predictors of negative spillover from family to work. Journal of Family Issues. 2004;25(2):241–261. [Google Scholar]

- Moore RS. The hangover: An ambiguous concept in workplace alcohol policy. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1998;25(1):49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Moore RS, Cunradi CB, Duke M, Ames GM. Dimensions of problem drinking among young adult restaurant workers. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35(5):329–333. doi: 10.1080/00952990903075042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhr T. ATLAS.ti Qualitative Software Package Version 5.0. Berlin: Scientific Software; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- National Restaurant Association. 2009 Restaurant Industry Pocket Factbook. Washington, DC: National Restaurant Association; 2009. Accessible at http://www.restaurant.org/pdfs/research/2009Factbook.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Pidd K, Boeckmann R, Morris M. Adolescents in transition: The role of workplace alcohol and other drug policies as a prevention strategy. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 2006;13(4):353–365. [Google Scholar]

- Roman P, Blum T. The workplace and alcohol problem prevention. Alcohol Research and Health. 2002;26(1):49–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003;15:85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Trice HM, Sonnenstuhl WJ. Constructive confrontation and other referral processes. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Vol. 6. New York: Plenum Press; 1988. pp. 159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Huang LX, Brittingham AM. Worker Drug Use and Workplace Policies and Programs: Results from the 1994 and 1997 NHSDA. Rockville, MD: US Department of HHS, SAMHSA; 1999. [Google Scholar]