Abstract

Protein biosynthesis requires aminoacyl-transfer RNA (tRNA) synthetases to provide aminoacyl-tRNA substrates for the ribosome. Most bacteria and all archaea lack a glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase (GlnRS); instead, Gln-tRNAGln is produced via an indirect pathway: a glutamyl-tRNA synthetase (GluRS) first attaches glutamate (Glu) to tRNAGln, and an amidotransferase converts Glu-tRNAGln to Gln-tRNAGln. The human pathogen Helicobacter pylori encodes two GluRS enzymes, with GluRS2 specifically aminoacylating Glu onto tRNAGln. It was proposed that GluRS2 is evolving into a bacterial-type GlnRS. Herein, we have combined rational design and directed evolution approaches to test this hypothesis. We show that, in contrast to wild-type (WT) GlnRS2, an engineered enzyme variant (M110) with seven amino acid changes is able to rescue growth of the temperature-sensitive Escherichia coli glnS strain UT172 at its non-permissive temperature. In vitro kinetic analyses reveal that WT GluRS2 selectively acylates Glu over Gln, whereas M110 acylates Gln 4-fold more efficiently than Glu. In addition, M110 hydrolyzes adenosine triphosphate 2.5-fold faster in the presence of Glu than Gln, suggesting that an editing activity has evolved in this variant to discriminate against Glu. These data imply that GluRS2 is a few steps away from evolving into a GlnRS and provides a paradigm for studying aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase evolution using directed engineering approaches.

INTRODUCTION

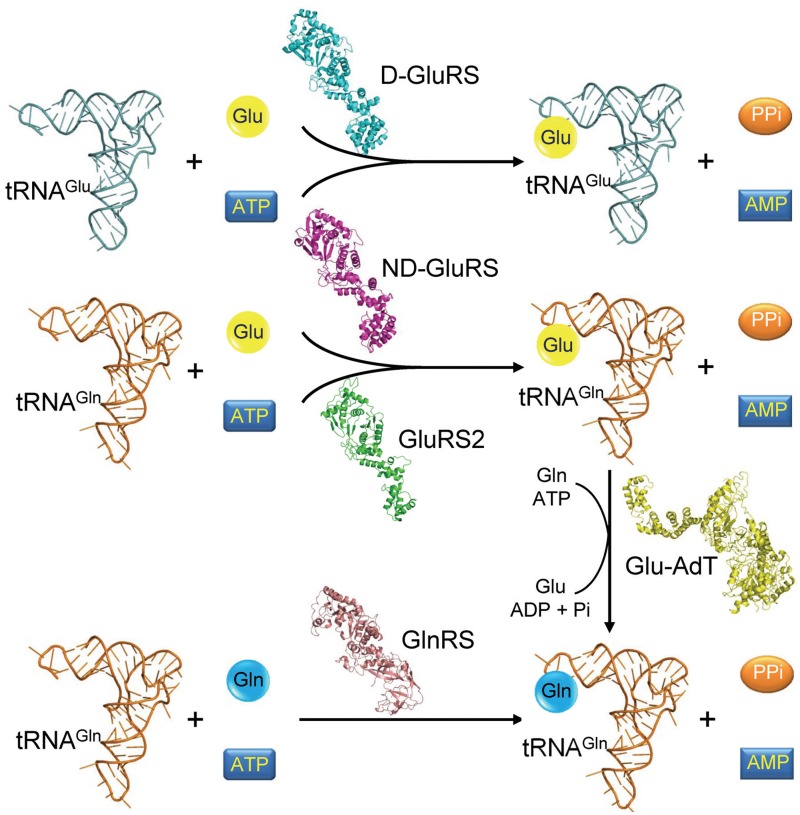

Translation of the genetic information from DNA to protein is a central process in all three domains of life (bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes). Protein synthesis on the ribosome requires aminoacyl-transfer RNA (aa-tRNA) substrates, which are formed by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs) and delivered to the ribosome by elongation factors (1–3). Except for selenocysteine, each of the 22 proteinogenic amino acids has a cognate aaRS that ligates it to the corresponding tRNAs, although several aa-tRNAs use indirect synthesis pathways in defined organisms (4). For example, a number of methanogenic archaea lack a cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase and produce Cys-tRNACys via a two-step pathway (5). Many bacteria and archaea do not encode an asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase; in such organisms, synthesis of Asn-tRNAAsn begins with misacylation of aspartate (Asp) to tRNAAsn by a non-discriminating (ND) aspartyl-tRNA synthetase, followed by conversion of Asp to Asn by an amidotransferase (AdT) (4). Similarly, most bacteria and all archaea lack a glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase (GlnRS) and use a Glu-AdT to produce Gln-tRNAGln from Glu-tRNAGln, which is synthesized by a glutamyl-tRNA synthetase (GluRS) (4,6) (Figure 1). In contrast, eukaryotes have evolved a GlnRS to directly synthesize Gln-tRNAGln (1).

Figure 1.

Pathways for Glu-tRNA and Gln-tRNA synthesis. Discriminating-GluRS (D-GluRS) selectively attaches Glu to tRNAGlu; ND-GluRS attaches Glu to both tRNAGlu and tRNAGln and GluRS2 specifically attaches Glu to tRNAGln. The resulting Glu-tRNAGln is converted to Gln-tRNAGln by Glu-AdT. Alternatively, Gln-tRNAGln is directly synthesized by GlnRS. The structures are taken from PDB 1QTQ, 3AL0 and 3AII.

In most bacteria and archaea, glutamate (Glu) is attached to both tRNAGlu and tRNAGln by a ND-GluRS. Certain bacteria (e.g. Helicobacter pylori) encode two types of GluRSs: GluRS1 that ligates Glu to tRNAGlu and GluRS2 that specifically attaches Glu to tRNAGln (7,8) (Figure 1). Phylogenetic and structural studies suggested that modern GluRSs and GlnRSs evolved from a common ancestral ND-GluRS (9). GlnRS evolved from ND-GluRS after the split between archaea and eukaryotes, and the gene encoding eukaryotic GlnRS was later transferred horizontally to certain bacterial species (e.g. Escherichia coli) (10–12). In this work, we have combined rational design and directed evolution approaches to obtain a H. pylori GluRS2 variant that is capable of rescuing a glnS temperature-sensitive E. coli strain (13,14), and aminoacylating Gln to tRNAGln in vitro. We have thus identified an important precursor that could further evolve into a bacterial-type GlnRS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids and protein purification

Escherichia coli UT172 glnS temperature-sensitive strain was used for selection of the H. pylori GluRS2 mutation library carried on pERS2 vector, which was derived from pUC18. Escherichia coli total tRNA used in this study was purchased from Roche. Wild-type (WT) and mutant H. pylori GluRS2 were cloned into pET20b vector for overexpression in the BL21(DE3) E. coli strain. Expression of WT GluRS2 was induced in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth with 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 1 h at 37°C when A600 reached 1.2. M110 GluRS2 formed inclusion bodies when overexpressed at 37°C. Its expression was thus induced at 30°C with 0.1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 5 h at A600 ∼1.2. The proteins were purified with Ni-NTA affinity resin (Qiagen) according to the standard procedures and dialyzed against a storage buffer containing 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 3 mM MgCl2 and 50% glycerol.

Construction and selection of H. pylori GluRS2 mutation library

To construct a pERS2 plasmid, the full-length gene encoding GluRS2 was inserted into pUC18 plasmid between EcoRI and PstI sites. An additional G nucleotide was included after the EcoRI site to allow GluRS2 controlled by Plac promoter.

Seven residues (A5, S7, E39, C178, I190, R192 and H196) located in the amino acid binding pocket of H. pylori GluRS2 were chosen based on the crystal structure of Thermus thermophilus GluRS:tRNAGlu (2CV0) to generate the mutation library. I190 and R192 were rationally mutated to serine and cysteine, respectively. A5, S7, E39, C178 and H196 were randomized. Overlap polymerase chain reaction was performed as described previously (15). 4 × 108 transformants were obtained for the library, which was 12 times larger than calculated library size (3.4 × 107).

The mutation library was selected in E. coli UT172 strain, in which mutants charging tRNAGln with glutamine would survive on LB plate supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 42°C. During the first round of selection, 1 μg plasmid was transformed into UT172 electro-competent cells to obtain 1 × 109 transformants. The transformants were recovered in 20 ml Super Optimal broth with Catabolite repression (SOC) at 30°C for 2 h, followed by the addition of 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 8 h of growth. 0.3 ml saturated culture was diluted into 15 ml SOC medium and grown for 5 h at 30°C. Next, 1 ml culture was spread on 20 × 20 cm LB plate supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and the plate was incubated at 42°C for 24 h. Colonies growing on the plate were scraped off and extracted for plasmids. The plasmids from the first round of selection were subjected to a second round of selection with the same procedure.

Enzymatic assays

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP)–pyrophosphate (PPi) exchange reaction was performed in the buffer containing 100 mM Hepes–KOH, pH 7.2, 30 mM KCl, 12 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 2 mM KF, 5 mg/ml total E. coli tRNA, 5 mM ATP, 5 mM PPi, 0.1 μCi [γ-32P]ATP, 9 μM enzymes and 0.24–10 mM Glu and Gln. The 1 μl reaction mixture was spotted onto thin-layer chromatography (TLC) polyethylenimine (PEI) cellulose F plates (Merck). Then, the TLC plates were developed in 1 M KH2PO4 and 1 M urea to separate ATP and PPi. Detection and quantification of signals were performed as described before (16).

Aminoacylation assay was essentially performed as described before (8) with slight modifications. The 40 μl reaction mixture contained 100 mM Hepes–KOH, pH 7.2, 30 mM KCl, 12 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 5 mg/ml total E. coli tRNA, 5 mM ATP, 40 μM [14C]Glu or [3H]Gln and 2.3 μM enzymes; 8 μl aliquots were taken out at each time point for scintillation counting.

ATP consumption was performed in the presence of 100 mM Hepes–KOH (pH 7.2), 30 mM KCl, 12 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 5 mg/ml total E. coli tRNA, 0.1 μCi [α-32P]ATP, 1 mM cold ATP, 10 mM Glu or Gln and 9 μM GluRS2. At each time spot, a 2 -μl aliquot was quenched with 2 μl acetic acid. The 1 μl resulting mixture was spotted on PEI cellulose plates and separated in 0.1 M ammonium acetate and 5% acetic acid. The Adenosine monophosphate (AMP)/ATP ratios were quantified with phosphorimaging. No aminoacyl adenylate spot was observed during the reaction time course.

RESULTS

Design and evolution of a GluRS2 variant that rescues a glnS temperature-sensitive strain

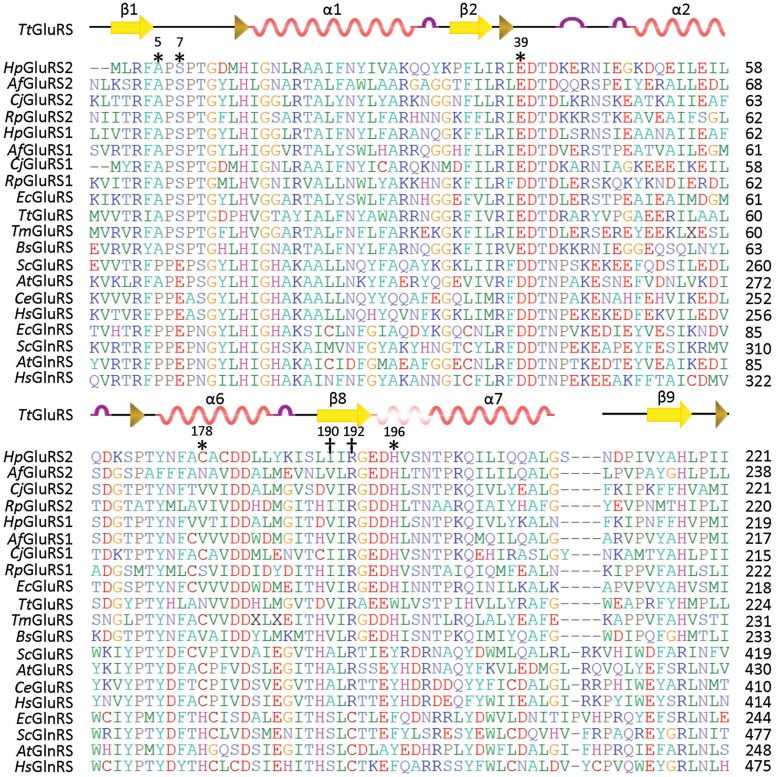

Previous studies have shown that unlike ND-GluRS that aminoacylates Glu to both tRNAGlu and tRNAGln, H. pylori GluRS2 (HpGluRS2) specifically charges Glu to tRNAGln, indicating that GluRS2 may be on the way to evolve into a bacterial-type GlnRS that is distinct from the eukaryotic-type GlnRS found in modern organisms (7,8). Phylogenetic analyses have shown that GluRS2 is closely related to bacterial GluRSs but is more distant from GlnRSs present in eukaryotes and certain bacteria (9). Our sequence alignment revealed multiple active site residues that have distinct patterns in GluRS and GlnRS proteins (Figure 2). For example, position 190 (H. pylori GluRS2 numbering) is either an isoleucine or valine in bacterial GluRSs but is changed to a conserved serine in GlnRSs, and R192 of HpGluRS2 corresponds to a cysteine in GlnRSs. The crystal structure of T. thermophilus GluRS shows that these two residues interact with the side chain of the substrate Glu in the presence of tRNA (17) (Figure 3). The structures of E. coli GlnRS also reveal that S227 and C229 (corresponding to I190 and R192 in HpGluRS2, respectively) are located close to the side chain of Gln at the active site (18,19).

Figure 2.

Sequence alignment of the GluRS/GlnRS family proteins. The residues that are rationally engineered in this work are indicated by daggers and the randomized residues are asterisked. Hp, Helicobacter pylori; Af, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans; Cj, Campylobacter jejuni; Rp, Rickettsia prowazekii; Ec, Escherichia coli; Tt, Thermus thermophilus; Tm, Thermotoga maritima; Bs, Bacillus subtilis; Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans and Hs, Homo sapiens.

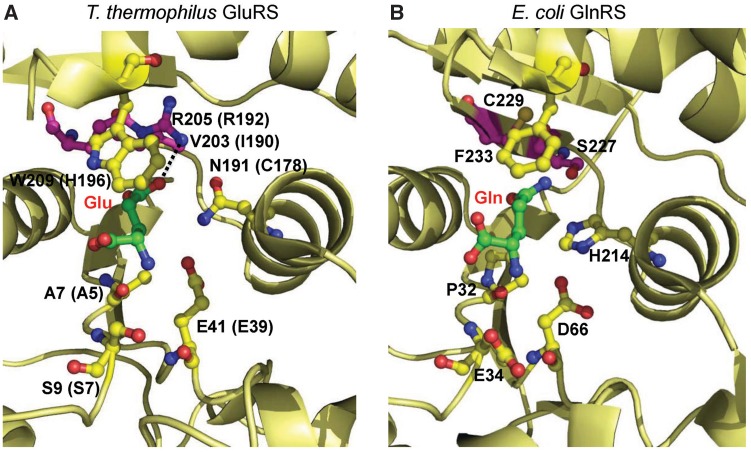

Figure 3.

Active sites of GluRS and GlnRS. The crystal structures of (A) T. thermophilus GluRS (2CV0) and (B) E. coli GlnRS (1O0B) are shown. In parentheses are corresponding residues in H. pylori GluRS2. The rationally mutated residues are shown in purple and randomized residues are shown in blue.

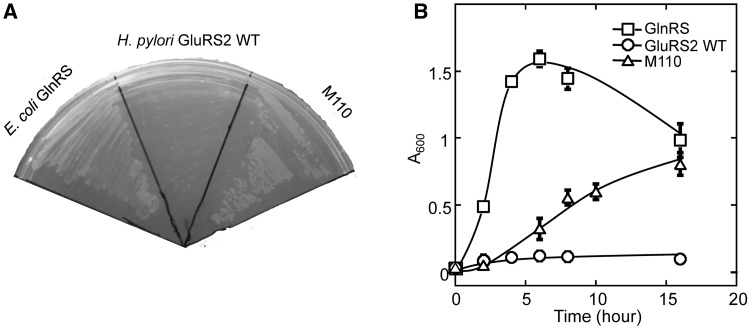

To evolve HpGluRS2 into a GlnRS, we rationally introduced mutations I190S and R192C. We further randomized five active site residues that are important for amino acid binding based on the structure of T. thermophilus GluRS (17) (Figure 3). The plasmid library expressing randomized HpGluRS2 was transformed into E. coli strain UT172, which harbored a temperature-sensitive glnS gene (13,14). This E. coli strain was not able to grow at 42°C due to a defect in Gln-tRNAGln synthesis, and as expected, WT HpGluRS2 did not complement growth at 42°C (Figure 4). Selection of the transformed library at 42°C led to one GluRS2 variant (named M110) that rescued the growth of UT172 (Figure 4). Growth analysis revealed that UT172 transformed with M110 exhibited a doubling time of 94 min at 42°C, compared with 32 min for the strain transformed with E. coli GlnRS (Figure 4B). Sequencing results showed that M110 contained mutations A5L, S7R, E39R, C178L, I190S, R192C and H196Q. The in vivo complementation assay suggested that M110 GluRS2 likely supplied the E. coli cells with sufficient Gln-tRNAGln to support growth. Alternatively, M110 GluRS2 might possess a higher Glu-tRNAGln synthesis activity than the WT at 42°C, and Glu misincorporation at Gln codons rescued the growth of UT172. Such possibilities were further investigated using biochemical assays in vitro.

Figure 4.

Complementation of the glnS temperature-sensitive E. coli strain UT172. (A) GlnRS and M110 GluRS2, but not WT GluRS2, are able to rescue the growth of strain UT172 at 42°C on LB plates. (B) UT172 expressing M110 shows a slower growth rate compared with the strain expressing E. coli GlnRS at 42°C in LB broth. The results are the average of at least four repeats with standard deviations indicated.

M110 GluRS2 has evolved a GlnRS activity

To probe the amino acid specificity of the evolved enzyme, we purified the WT and M110 GluRS2 variants and performed in vitro pyrophosphate exchange experiments, which measured the activation of amino acids with ATP. To our surprise, WT GluRS2 exhibited similar activation efficiencies (determined by the kcat/Km value) for Glu and Gln (Table 1). Both the kcat and Km values for Gln were ∼2-fold lower than Glu. Conversely, the M110 variant showed 2.3-fold preference for Gln over Glu. The Gln activation efficiency was 9-fold higher for M110 than WT due to increased kcat and decreased Km values.

Table 1.

Pyrophosphate exchange activities of WT and M110 GluRS2 at 37°C

| Glu |

Gln |

Selectivity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (×10−3 s−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (×10−3 mM−1 s−1) | kcat (×10−3 s−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (×10−3 mM−1 s−1) | (Gln/Glu) | |

| WT | 18 ± 0.1 | 0.44 ± 0.07 | 41 ± 7 | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 49 ± 11 | 1.2 |

| M110 | 18 ± 0.4 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 190 ± 40 | 26 ± 2 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 430 ± 110 | 2.3 |

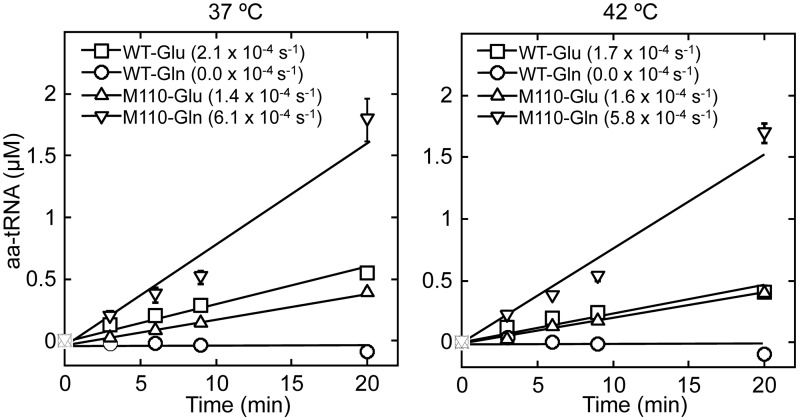

Next, we measured aminoacylation activities of WT and M110 GluRS2. Despite similar amino acid activation efficiencies, WT GluRS2 only attaches Glu, but not Gln, to tRNAGln at both 37 and 42°C (Figure 5). M110 showed 4-fold increased aminoacylation efficiency for Gln than Glu, confirming that this variant had evolved a GlnRS activity. M110 still maintained the Glu charging activity, although it was reduced by 30% compared with the WT GluRS2 at 37°C. The WT and M110 variants showed almost identical Glu charging efficiency at 42°C. Given that only M110 but not the WT GluRS2 rescued the glnS temperature-sensitive strain, our aminoacylation data suggested that instead of Glu-tRNAGln production, the Gln-tRNAGln synthesis activity that had evolved in M110 was responsible for rescuing the growth phenotype of UT172.

Figure 5.

Aminoacylation by GluRS2 variants. WT GluRS2 (2.3 μM) charges Glu (40 μM) but not Gln (40 μM) to tRNAGln (5 mg/ml total E. coli tRNA containing 3 μM tRNAGln as determined by plateau charging), whereas M110 (2.3 μM) preferentially aminoacylates Gln over Glu at both 37 and 42°C.

M110 GluRS2 uses an editing mechanism to reduce aminoacylation of Glu to tRNAGln

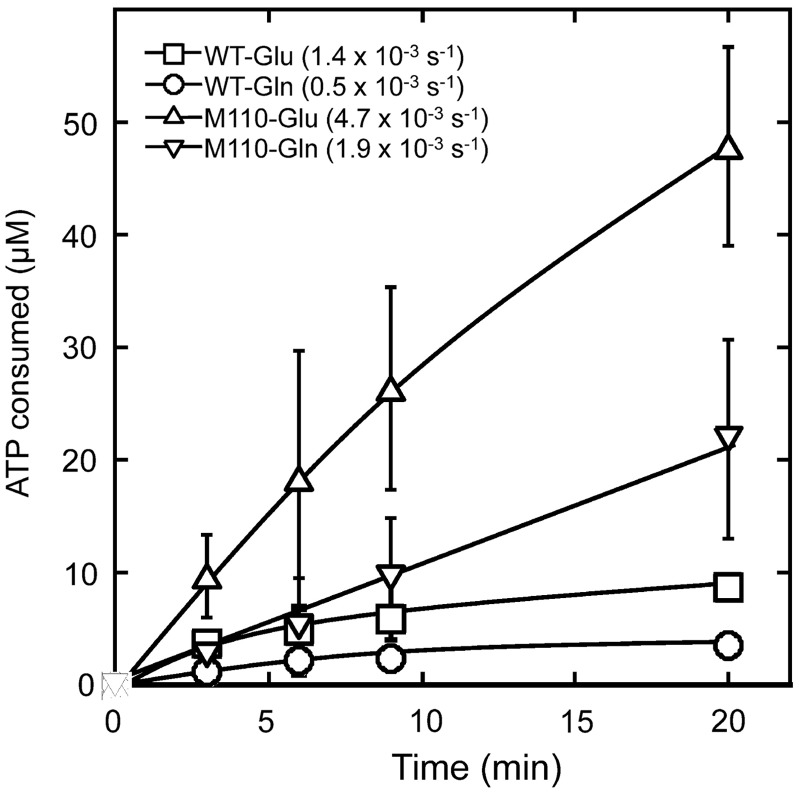

The discrepancies between amino acid activation and aminoacylation results led us to investigate whether a quality control mechanism might help GluRS2 variants to discriminate between Glu and Gln. It has been previously shown that E. coli GlnRS hydrolyzes glutaminyl adenylate (Gln-AMP) in the presence of tRNA (20), mimicking a pre-transfer editing activity discovered in other aaRSs (21–24). We measured the hydrolysis of [α-32P]ATP by WT and M110 GluRS2 in the presence of tRNA and Glu or Gln (Figure 6). WT GluRS2 hydrolyzed ATP about 3-fold more slowly in the presence of Gln than Glu, suggesting that the WT enzyme does not use an editing activity to prevent Gln from being attached to tRNAGln. Rather, the activated Gln-AMP is likely positioned in a non-productive fashion at the active site of WT GluRS2, restricting the transfer of Gln to tRNA. The M110 variant showed 3-fold higher ATP hydrolysis rate than the WT in the presence of Glu, and the end point of hydrolyzed ATP was 15-fold higher than the available pool of tRNAGln in the reaction (Figure 6). This suggests that M110 uses an editing mechanism to selectively hydrolyze activated Glu-AMP. Collectively, our results indicate that M110 uses both kinetic discrimination and editing mechanisms to preferentially aminoacylate Gln over Glu.

Figure 6.

ATP hydrolysis by GluRS2 variants. M110 (9 μM) hydrolyzes ATP 2.5-fold faster in the presence of Glu (10 mM) than Gln (10 mM) at 37°C, suggesting that this mutant discriminates against Glu using an editing mechanism.

DISCUSSION

Evolution of the GluRS/GlnRS family enzymes

It has been widely accepted that the indirect pathway of Gln-tRNAGln synthesis predates the direct pathway and that GlnRS was absent in the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) (4,10,12). The GluRS in LUCA was a ND enzyme and charged Glu to both tRNAGlu and tRNAGln (Figure 1). Glu-tRNAGln was then converted to Gln-tRNAGln by a Glu-AdT (GatCAB in chloroplasts and mitochondria of bacteria; GatFAB in mitochondria of yeast and GatDE in archaea) (4,25–28). GlnRS evolved in early eukaryotes from a duplicated ND-GluRS to gain specificity for Gln and tRNAGln and was later transferred to certain bacteria (9,29). A group of proteobacteria, including H. pylori, acquired a second GluRS (GluRS2) through horizontal gene transfer. GluRS2 specifically recognizes tRNAGln, leading to the hypothesis that it has been evolving to become a bacterial-type GlnRS (7,8). We show here that WT H. pylori GluRS2 already possesses the power to activate Gln, yet the resulting Gln-AMP may not be correctly positioned for the transfer of the amino acid moiety to tRNA. Our engineered GluRS2 variant (M110) has gained Gln charging activity and thus represents an important precursor towards the evolution of a bacterial-type GlnRS. The aminoacylation activities of our GluRS2 variants are low compared with previously published results (30), presumably because to be consistent with our in vivo tests, we have used total E. coli tRNA instead of purified H. pylori tRNAGln. The heterologous tRNA used and the competition from non-cognate tRNAs could decrease the aminoacylation efficiency of GluRS2.

Structural insights into substrate recognition by WT and M110 GluRS2

WT GluRS2 specifically attaches Glu (but not Gln) to tRNA, although it also activates Gln during the pyrophosphate exchange assay (Figure 5 and Table 1). In contrast, the M110 variant acylates Gln 4-fold more efficiently than Glu (Figure 5). We propose that WT GluRS2 binds activated Gln-AMP in a mode not suitable for aminoacylation. Structural studies of T. thermophilus GluRS reveal that R205 (equivalent of R192 in H. pylori GluRS2 and C229 in E. coli GlnRS) directly interacts with the side-chain oxygen of Glu (Figure 3). This residue might serve as a negative determinant for proper positioning of Gln-AMP during the amino acid transfer step. The evolved M110 variant contains a R192C mutation, which could be critical for glutaminylation. In line with this notion, a C229R mutation has been shown to significantly improve the Km of E. coli GlnRS for Glu (31). It is interesting that the M110 variant maintains the same glutamylation activity as in the WT, presumably due to the cumulative effects of other mutations present in M110.

Quality control mechanisms in natural and engineered aaRSs

Selection of the correct amino acid is a big challenge for many aaRSs due to the structural and chemical similarities between amino acids. To maintain translational fidelity, such aaRSs use editing mechanisms to hydrolyze incorrect aminoacyl adenylates (pre-transfer editing) or aa-tRNAs (post-transfer editing) (32,33), whereas post-transfer editing requires a separate editing domain or a free-standing protein (34–36) and pre-transfer editing mainly occurs at the active site (21,37,38). It is intriguing that our engineered M110 GluRS2 appears to have evolved an editing mechanism to discriminate against Glu in favor of Gln (Figure 6). GluRS2 lacks a post-transfer editing domain, prompting us to hypothesize that M110 uses a pre-transfer editing strategy to hydrolyze activated Glu-AMP, presumably at the active site resembling E. coli GlnRS (20). It is worth noting that a recent study shows that WT GluRS2 modestly increases the hydrolysis of Glu-tRNAGln by an unknown mechanism (30). The fidelity mechanism for GluRS2 thus remains to be addressed in future studies. Should editing occur at the active site before amino acid transfer, a water molecule is likely required for hydrolysis of Glu-AMP and Gln-AMP. We have recently shown that yeast mitochondrial threonyl-tRNA synthetase edits seryl adenylate faster than threonyl adenylate due to the minor movement of a potential catalytic water molecule (Ling et al., unpublished work). A similar mechanism could explain the preferential hydrolysis of Glu-AMP over Gln-AMP by M110, which needs to be clarified by future structural studies.

Engineering aaRSs towards expanded substrate recognition

Several aaRSs have been successfully engineered to co-translationally incorporate a variety of unnatural amino acids into proteins in bacteria and eukaryotes (15,39–46). Both rational design and directed evolution methods have been used for unnatural amino acid incorporation, yet only a few studies have used such methods to understand the evolution of natural aaRSs. A rationally engineered E. coli GlnRS has obtained a misacylation activity to produce Glu-tRNAGln (31), and transplanting the GlnRS acceptor stem loop to an archaeal ND-GluRS makes it specifically recognize tRNAGln (29). In this work, we have combined rational design and directed evolution approaches to understand the evolutionary potential from GluRS2 to GlnRS. Such a strategy could be used as a model to investigate how primordial aaRSs have acquired new functions to become the enzymes present in modern organisms.

FUNDING

Funding for open access charge: National Institute of General Medical Sciences [GM022854 to D.S.].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Kelly Sheppard (Skidmore College), Patrick O'Donoghue and Ilka Heinemann (Yale University) for insightful discussion and comments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ibba M, Söll D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:617–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steitz TA. A structural understanding of the dynamic ribosome machine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:242–253. doi: 10.1038/nrm2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dale T, Uhlenbeck OC. Amino acid specificity in translation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:659–665. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheppard K, Yuan J, Hohn MJ, Jester B, Devine KM, Söll D. From one amino acid to another: tRNA-dependent amino acid biosynthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:1813–1825. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sauerwald A, Zhu W, Major TA, Roy H, Palioura S, Jahn D, Whitman WB, Yates JR, 3rd, Ibba M, Söll D. RNA-dependent cysteine biosynthesis in archaea. Science. 2005;307:1969–1972. doi: 10.1126/science.1108329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nureki O, Vassylyev DG, Katayanagi K, Shimizu T, Sekine S, Kigawa T, Miyazawa T, Yokoyama S, Morikawa K. Architectures of class-defining and specific domains of glutamyl-tRNA synthetase. Science. 1995;267:1958–1965. doi: 10.1126/science.7701318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skouloubris S, Ribas de Pouplana L, De Reuse H, Hendrickson TL. A noncognate aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase that may resolve a missing link in protein evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11297–11302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932482100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salazar JC, Ahel I, Orellana O, Tumbula-Hansen D, Krieger R, Daniels L, Söll D. Coevolution of an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase with its tRNA substrates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:13863–13868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1936123100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nureki O, O’Donoghue P, Watanabe N, Ohmori A, Oshikane H, Araiso Y, Sheppard K, Söll D, Ishitani R. Structure of an archaeal non-discriminating glutamyl-tRNA synthetase: a missing link in the evolution of Gln-tRNAGln formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7286–7297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamour V, Quevillon S, Diriong S, N’Guyen VC, Lipinski M, Mirande M. Evolution of the Glx-tRNA synthetase family: the glutaminyl enzyme as a case of horizontal gene transfer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:8670–8674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woese CR, Olsen GJ, Ibba M, Söll D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, the genetic code, and the evolutionary process. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000;64:202–236. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.1.202-236.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Donoghue P, Luthey-Schulten Z. On the evolution of structure in aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003;67:550–573. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.550-573.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Englisch-Peters S, Conley J, Plumbridge J, Leptak C, Söll D, Rogers MJ. Mutant enzymes and tRNAs as probes of the glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase: tRNAGln interaction. Biochimie. 1991;73:1501–1508. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weygand-Durasevic I, Schwob E, Söll D. Acceptor end binding domain interactions ensure correct aminoacylation of transfer RNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:2010–2014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park HS, Hohn MJ, Umehara T, Guo LT, Osborne EM, Benner J, Noren CJ, Rinehart J, Söll D. Expanding the genetic code of Escherichia coli with phosphoserine. Science. 2011;333:1151–1154. doi: 10.1126/science.1207203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo LT, Chen XL, Zhao BT, Shi Y, Li W, Xue H, Jin YX. Human tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase is switched to a tRNA-dependent mode for tryptophan activation by mutations at V85 and I311. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5934–5943. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sekine S, Shichiri M, Bernier S, Chenevert R, Lapointe J, Yokoyama S. Structural bases of transfer RNA-dependent amino acid recognition and activation by glutamyl-tRNA synthetase. Structure. 2006;14:1791–1799. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rath VL, Silvian LF, Beijer B, Sproat BS, Steitz TA. How glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase selects glutamine. Structure. 1998;6:439–449. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bullock TL, Uter N, Nissan TA, Perona JJ. Amino acid discrimination by a class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase specified by negative determinants. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;328:395–408. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gruic-Sovulj I, Uter N, Bullock T, Perona JJ. tRNA-dependent aminoacyl-adenylate hydrolysis by a nonediting class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:23978–23986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boniecki MT, Vu MT, Betha AK, Martinis SA. CP1-dependent partitioning of pretransfer and posttransfer editing in leucyl-tRNA synthetase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:19223–19228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809336105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hendrickson TL, Nomanbhoy TK, Crécy-Lagard V, Fukai S, Nureki O, Yokoyama S, Schimmel P. Mutational separation of two pathways for editing by a class I tRNA synthetase. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:353–362. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00449-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Splan KE, Ignatov ME, Musier-Forsyth K. Transfer RNA modulates the editing mechanism used by class II prolyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:7128–7134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minajigi A, Francklyn CS. Aminoacyl transfer rate dictates choice of editing pathway in threonyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:23810–23817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.105320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pujol C, Bailly M, Kern D, Marechal-Drouard L, Becker H, Duchene AM. Dual-targeted tRNA-dependent amidotransferase ensures both mitochondrial and chloroplastic Gln-tRNAGln synthesis in plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:6481–6485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712299105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frechin M, Senger B, Braye M, Kern D, Martin RP, Becker HD. Yeast mitochondrial Gln-tRNAGln is generated by a GatFAB-mediated transamidation pathway involving Arc1p-controlled subcellular sorting of cytosolic GluRS. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1119–1130. doi: 10.1101/gad.518109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagao A, Suzuki T, Katoh T, Sakaguchi Y. Biogenesis of glutaminyl-mt tRNAGln in human mitochondria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:16209–16214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907602106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tumbula DL, Becker HD, Chang WZ, Söll D. Domain-specific recruitment of amide amino acids for protein synthesis. Nature. 2000;407:106–110. doi: 10.1038/35024120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Donoghue P, Sheppard K, Nureki O, Söll D. Rational design of an evolutionary precursor of glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:20485–20490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117294108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huot JL, Fischer F, Corbeil J, Madore E, Lorber B, Diss G, Hendrickson TL, Kern D, Lapointe J. Gln-tRNAGln synthesis in a dynamic transamidosome from Helicobacter pylori, where GluRS2 hydrolyzes excess Glu-tRNAGln. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:9306–9315. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bullock TL, Rodriguez-Hernandez A, Corigliano EM, Perona JJ. A rationally engineered misacylating aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:7428–7433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711812105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mascarenhas AP, An S, Rosen AE, Martinis SA, Musier-Forsyth K. Fidelity mechanisms of the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. In: RajBhandary UL, Köhrer C, editors. Protein Engineering. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 153–200. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ling J, Reynolds N, Ibba M. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis and translational quality control. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;63:61–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt E, Schimmel P. Mutational isolation of a sieve for editing in a transfer RNA synthetase. Science. 1994;264:265–267. doi: 10.1126/science.8146659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.An S, Musier-Forsyth K. Trans-editing of Cys-tRNAPro by Haemophilus influenzae YbaK protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:42359–42362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahel I, Korencic D, Ibba M, Söll D. Trans-editing of mischarged tRNAs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:15422–15427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136934100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.SternJohn J, Hati S, Siliciano PG, Musier-Forsyth K. Restoring species-specific posttransfer editing activity to a synthetase with a defunct editing domain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:2127–2132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611110104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu B, Yao P, Tan M, Eriani G, Wang ED. tRNA-independent pretransfer editing by class I leucyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:3418–3424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806717200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoo TH, Tirrell DA. High-throughput screening for methionyl-tRNA synthetases that enable residue-specific incorporation of noncanonical amino acids into recombinant proteins in bacterial cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2007;46:5340–5343. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Datta D, Wang P, Carrico IS, Mayo SL, Tirrell DA. A designed phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase variant allows efficient in vivo incorporation of aryl ketone functionality into proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:5652–5653. doi: 10.1021/ja0177096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang Y, Tirrell DA. Attenuation of the editing activity of the Escherichia coli leucyl-tRNA synthetase allows incorporation of novel amino acids into proteins in vivo. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10635–10645. doi: 10.1021/bi026130x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu W, Brock A, Chen S, Schultz PG. Genetic incorporation of unnatural amino acids into proteins in mammalian cells. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:239–244. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wan W, Huang Y, Wang Z, Russell WK, Pai PJ, Russell DH, Liu WR. A facile system for genetic incorporation of two different noncanonical amino acids into one protein in Escherichia coli. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2010;49:3211–3214. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chin JW, Cropp TA, Anderson JC, Mukherji M, Zhang Z, Schultz PG. An expanded eukaryotic genetic code. Science. 2003;301:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.1084772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neumann H, Peak-Chew SY, Chin JW. Genetically encoding N(epsilon)-acetyllysine in recombinant proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:232–234. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu CC, Schultz PG. Adding new chemistries to the genetic code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:413–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.105824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]