Abstract

Excessive exposure to manganese (Mn) increases levels of oxidative stressors and proinflammatory mediators, such as cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin E2. Mn also activates nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), an important mediator of inflammation. The signaling molecule 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15 d-PGJ2) is an anti-inflammatory prostaglandin. Here, we tested the hypothesis that 15 d-PGJ2 modulates Mn-induced activation of astrocytic intracellular signaling, including NF-κB and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2), a master regulator of antioxidant transcriptional responses. The results establish that 15 d-PGJ2 suppresses Mn-induced NF-κB activation by interacting with several signaling pathways. The PI3K/Akt pathway, which is upstream of NF-κB, plays a role in this activation, because (i) pretreatment with 15 d-PGJ2 (10 µM for 1 h) significantly (p<0.01) inhibited Mn (500 µM)-induced PI3K/Akt activation and (ii) inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway with LY29004 significantly (p<0.05) decreased NF-κB activation. 15 d-PGJ2 also significantly (p<0.05) attenuated Mn-induced astrocytic NF-κB activation by inhibiting the Mn-induced phosphorylation of IκB kinase and subsequent IκB-α degradation. Because Mn-induced oxidative stress is also associated with Nrf2 activation, additional studies addressed the ability of 15 d-PGJ2 to modulate the Nrf2 pathway. 15 d-PGJ2 significantly (p<0.01) increased Nrf2 expression in whole-cell lysates. Consistent with its pro-oxidant properties, Mn also increased Nrf2 expression. Nevertheless, cotreatment of whole-cell lysates with both Mn and 15 d-PGJ2 partially suppressed (p<0.01) the 15 d-PGJ2-induced increase in astrocytic Nrf2 protein expression. Mn treatment also decreased (p<0.001) expression of DJ-1, a Parkinson disease-associated protein and a stabilizer of Nrf2, and 15 d-PGJ2 attenuated Mn-induced astrocytic inhibition of DJ-1 expression. Collectively, these results demonstrate that 15 d-PGJ2 exerts a protective effect in astrocytes against Mn-induced inflammation and oxidative stress by modulating the activation of the NF-κB and Nrf2 signaling pathways.

Keywords: Manganese, Neurotoxicity, 15 d-PGJ2, Nrf2, NF-κB, Free radicals

Manganese (Mn) is an essential trace element for numerous cellular enzyme reactions, including those of glutamine synthase, arginase, and mitochondrial superoxide dismutase [1,2]. However, excessive brain Mn accumulation causes an abnormal neurological syndrome with marked clinical resemblance to Parkinson disease (PD), referred to as manganism [3]. The mechanisms by which Mn induces neurotoxicity are not completely understood, but oxidative stress, neurotransmitter metabolism dyshomeostasis, and glial inflammation may mediate its effects [4–6]. Mn activates glial cells, increasing proinflammatory mediator expression [7–9], which causes neuroinflammation, release of proinflammatory cytokines, breaching of blood–brain barrier permeability, and leukocyte invasion.

Prostaglandins (PGs) are signaling molecules with diverse biological activities [10,11], including inflammation, thrombosis, and calcium regulation. PGs are synthesized from arachidonic acid released from membrane phospholipids by phospholipase A2. The major signaling pathway of PGs involves binding to G-protein-coupled receptors at the plasma membrane and nuclear orphan receptors [10]. A subclass of PGs may also affect multiple additional targets. For example, intracellular levels of 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15 d-PGJ2) generated from PGD2 by spontaneous or induced dehydration [12–14] increase under inflammatory conditions [15]. 15d-PGJ2 has anti-inflammatory properties [12], possessing high affinity for PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ) [16,17]. Upon binding to 15 d-PGJ2, PPARγ translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, where it initiates transcription of a large number of genes that contain a PPARγ-responsive element in their promoter sequence [18].

The cellular effects of 15 d-PGJ2 are also PPARγ-independent [19]. 15 d-PGJ2 can covalently modify several proteins and affect their function. For example, 15 d-PGJ2 modulates nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathways [13,20] and attenuates NF-κB signaling by inhibiting the degradation of IκB, the nuclear translocation of p65, and the activation of PI3K/Akt [19]. 15 d-PGJ2 binds to cysteine in the IκB kinase (IKK) sequence, which phosphorylates IκB, the inhibitor of the transcription factor NF-κB. This binding reduces the proinflammatory effects of IκB kinase-activating cytokines, partially explaining the anti-inflammatory effects of 15 d-PGJ2 [21,22]. In addition to its function as an endogenous signaling molecule, exogenously supplemented 15 d-PGJ2 induces anti-inflammatory effects [12] by inhibiting the CRM1-dependent nuclear protein export pathway [23].

15 d-PGJ2 also reduces inflammation by activating nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2), an oxidative stress-responsive transcription factor. Nrf2 is sequestered in the cytoplasm by binding to a cytoskeletal protein, Keap1. Upon oxidative stress, Nrf2 is released from its repressor protein, Keap1, and translocates to the nucleus where it interacts with the antioxidant-response element (ARE) located in the promoter sequence of Nrf2-responsive genes [24,25]. 15 d-PGJ2 induces the dissociation and subsequent translocation of “free” Nrf2 to the nucleus by directly binding to a cysteine linker region on Keap1 via covalent linkage [26,27].

Nrf2 is regulated by DJ-1 and mutations in the DJ-1 gene induce juvenile parkinsonism [28]. Loss-of-function mutations of DJ-1 lead to selective neurodegeneration of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons, characteristic of PD and manganism [28,29]. DJ-1 promotes cell survival and protects cells from oxidative stress [30], but the mechanisms by which DJ-1 induces cytoprotection have yet to be completely understood. Notably, Nrf2 is unstable in the absence of DJ-1, resulting in attenuated Nrf2-regulated transcriptional responses [31]. DJ-1 is also required for stabilization of Nrf2 by preventing its association with Keap1, which prevents Nrf2's subsequent ubiquitination [31].

Because Mn induces cytotoxic effects in astrocytes via oxidative stress and inflammation, and given the role of 15 d-PGJ2 in regulating intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, this series of studies was designed to test the hypothesis that 15 d-PGJ2 offers protective effects against Mn toxicity in astrocytes. Specifically, we aimed to characterize the modulatory effects of 15 d-PGJ2 on the astrocytic NF-κB and Nrf2 signaling pathways in response to Mn treatment.

Materials and methods

Materials

Manganese chloride (MnCl2) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), 15 d-PGJ2 from Cayman (Ann Arbor, MI, USA), LY29004 from Tocris (Ellisville, MO, USA). Minimal essential medium (MEM) with Earle's salts, heat-inactivated horse serum, penicillin, and streptomycin were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). All other chemicals and supplies were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburg, PA, USA), unless otherwise specified.

Primary cultures of rat astrocytes

Primary cultures of astrocytes were prepared according to previously established protocols [32] in a protocol approved by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. One-day-old Sprague–Dawley rats were decapitated under halothane anesthesia and the cerebral cortices were dissected out and digested with bacterial neutral protease (dispase; Invitrogen). Dissociated astrocytes were then plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells/ml. Twenty-four hours after the initial plating, the medium was changed to preserve the adhering astrocytes and to remove neurons and oligodendrocytes. The cultures were grown at 37 °C in a 95% air/5% CO2 incubator for 3 weeks in MEM with Earle's salts supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. The medium was changed twice a week. The surface-adhering monolayer cultures were >95% positive for the astrocyte-specific marker glial fibrillary acidic protein. All experiments were performed 3 weeks after isolation, when cultures were confluent.

Astrocyte treatments

Astrocytes (3 weeks old) were incubated with 500 µM MnCl2 for 6 h or the indicated time in the presence or absence of 15 d-PGJ2 (10 µM) for 2 h. When treated with the PI3K/Akt inhibitor, astrocytes were preincubated with LY29004 (20 µM) [33] for the indicated times. Toxic Mn concentrations present in relevant mammalian cells can be estimated from the literature. For example, weekly injections of Mn over a 3-month period in the striatum and glubos pallidus (GP) of monkeys (0, 2.25, 4.5, and 9 g) produce dose-related clinical signs that are more severe in the higher dose ranges. At the highest dose, the Mn concentration is increased 12-fold in the striatum and 9-fold in the GP [34]. The “physiological range” (no symptoms) is ~75–100 µM, and clinical signs increase in frequency and severity above this level, suggesting this concentration is near the threshold of toxicity. Accordingly, a 500 µM Mn concentration, deemed to be toxic, was chosen for the present series of studies.

Subcellular fractionation and detection of NF-κB and Nrf2 levels and localization

After treatment, astrocytes were lysed in ice-cold hypotonic buffer containing 10 mM Hepes, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma–Aldrich). After 30 min incubation on ice, the samples were centrifuged at 4 °C at 12,000 g for 3 min and the supernatant (cytosolic fraction) was collected. The pellet was extracted for 30 min in a high-salt lysis buffer containing 50 mM Hepes, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma–Aldrich). After 10 min centrifugation at 4 °C at 12,000 g for 3 min, the supernatant (nuclear fraction) was collected. Ku-86, a nuclear protein, was used for the normalization of the NF-κB protein content in the nuclear fraction. Mitochondrial fractionation was performed with a mitochondria fractionation kit (Abcam, Boston, MA, USA).

Western blot analysis

After treatments with designated compounds, astrocytes were washed with HBSS and lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma–Aldrich). Cell lysates were sonicated and centrifuged at 4 °C at 10,000 g for 5 min and the supernatant was used for protein quantification with the bicinchoninic acid (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) protein assay kit. An equal amount of protein (30 µg) from each sample was separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Immunoblot analysis was carried out with the primary antibodies, rabbit anti-NF-κB (1:2000), rabbit anti-Nrf2 (1:1000), rabbit anti-pAkt (1:2000), rabbit anti-Akt (1:1000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and mouse anti-β-actin (1:2000) (A1978; Sigma–Aldrich). Secondary antibodies were mouse anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (1:2000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and donkey anti-mouse IgG conjugated with HRP (1:2000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using the RNeasy Mini RNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The evaluation of mRNA levels of DJ-1 was performed by semiquantitative RT-PCR with GAPDH as a control as described previously [35]. The primers were the following: for DJ-1, 5′-TGGCTCACGAAGTAGGCTTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGGGCTTGGGCTCTCTAGTC-3′ (reverse), and for GAPDH, 5′-TCCCTCAAGATTGTCAGCAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGATCCACAACGGATACATT-3′ (reverse), to yield products of 247 and 300 bp, respectively, with 30 PCR cycles.

Immunocytochemistry

At the end of the treatments, astrocytes were washed twice with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and fixed with 100% methanol for 10 min at room temperature. After being rinsed in TBS containing 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, the cells were incubated with TBS containing 5% normal goat serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 (TGT) for 30 min at room temperature. Cultures were incubated overnight at 4 °C in TGT containing rabbit anti-NF-κB (1:250, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After being rinsed in TBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, the cells were incubated for 2 h at room temperature in TGT containing anti-rabbit IgG–TRITC conjugates (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). In addition, in separate experiments, primary or secondary antibodies were omitted to test for the specificity and possible cross-reaction. To visualize cell nuclei, cells were rinsed and coverslips were mounted with Vectashield solution containing DAPI. Images were taken with a Nikon confocal microscope (A1R laser scanning confocal; Melville, NY, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means±SEM relative to controls (standardized to 1). The data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test with statistical significance set at p<0.05. When the overall significance resulted in the rejection of the null hypothesis (p<0.05), the source of the variance was determined with the Tukey–Kramer test. All analyses were carried out with GraphPad software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Each experiment was carried out in three or more independently cultured primary astrocyte preparations.

Results

15d-PGJ2 inhibits the Mn-induced phosphorylation of PI3K/Akt

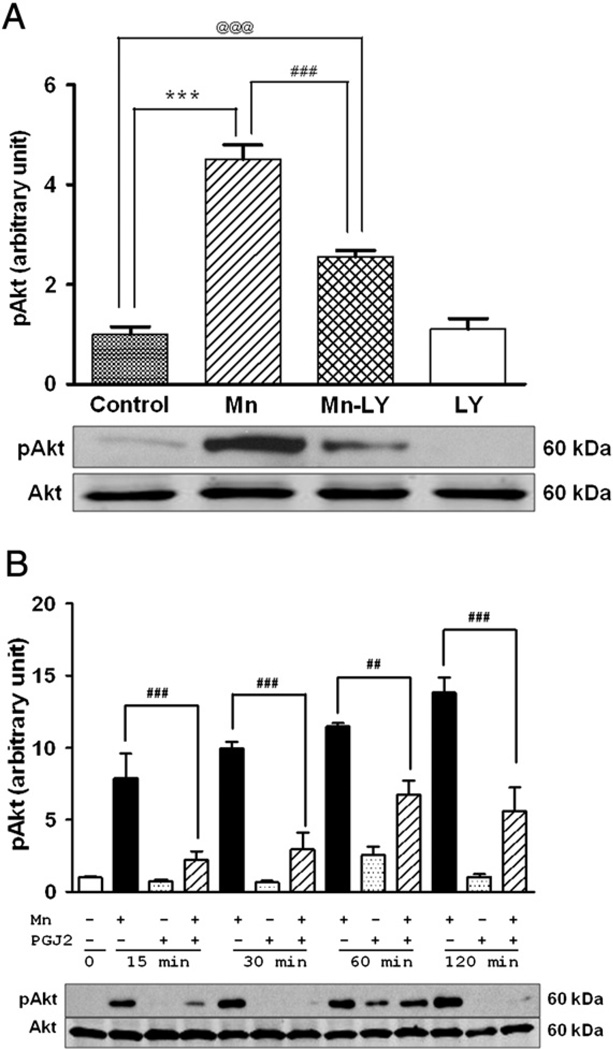

PI3K/Akt phosphorylation is upstream of NF-κB activation [19] and Mn is known to activate this pathway [36]. Accordingly, as a first step, we examined whether 15 d-PGJ2 protects against the cytotoxic effects of Mn. LY29004 (20 µM) [33], a specific inhibitor of PI3K/Akt, was used as a positive control (Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig. 1, Mn treatment (6 h) readily activated PI3K/Akt (with pAkt levels increasing by approximately fourfold over control levels, Fig. 1A) and this effect was attenuated by LY29004 (Fig. 1A), as well as 15 d-PGJ2 (Fig. 1B). 15 d-PGJ2 alone did not activate PI3K/Akt, but 2 h pretreatment of astrocytes with 15 d-PGJ2 before 6 h Mn treatment (total treatment with 15 d-PGJ2 of 8 h) significantly attenuated Mn-induced activation of PI3K/Akt. As shown in Fig. 1B, 15 d-PGJ2 significantly blocked PI3K/Akt activation at multiple time points (15, 30, 60, and 120 min) when astrocytes were pretreated for 2 h with 15 d-PGJ2 (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

15d-PGJ2 inhibits the Mn-induced activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway in astrocytes. Astrocytes were pretreated with LY290047 (20 µM) for 1 h before treatment with Mn (500 µM). (A) Mn increased phosphorylation of Akt; LY20094, an inhibitor of this pathway, blocked the Mn-induced activation of pAkt. Mn increased the phosphorylation of Akt within as little as 15 min of treatment. (B) 2 h pretreatment with 15 d-PGJ2 (10 µM) before Mn (500 µM) treatment blocked the Mn-induced activation of Akt at multiple time points. Data are means±SEM (n=4). ***p<0.001 compared to the controls; ##p<0.01, ###p<0.001 compared to the matched groups; @@@p<0.001.

15d-PGJ2 inhibits the Mn-induced phosphorylation of IKK

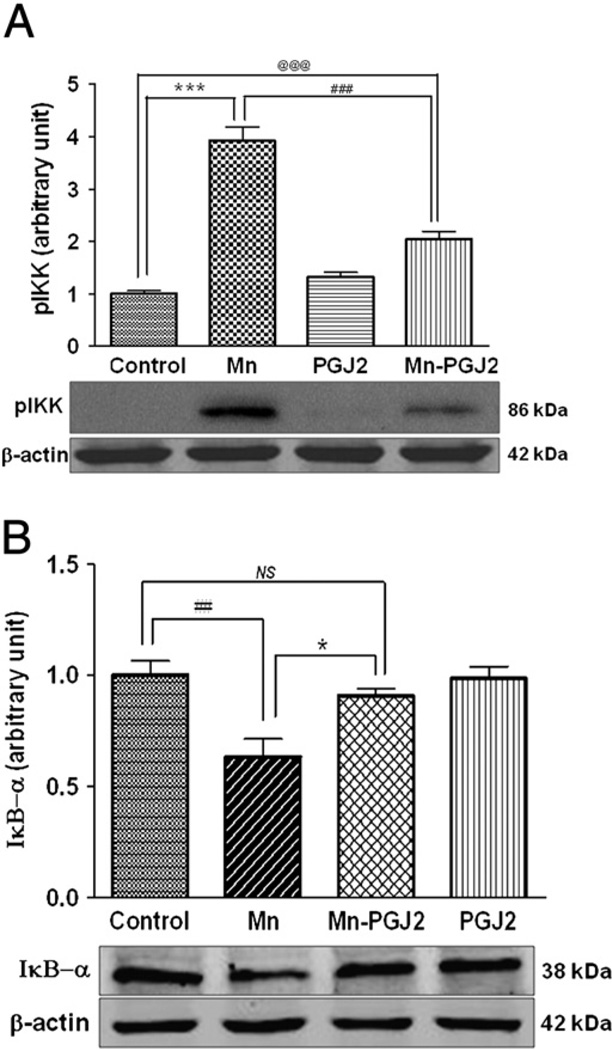

NF-κB mediates cellular responses to stimuli such as oxidative stress and inflammation [36,37]. Under resting conditions, the NF-κB complex is sequestered in the cytoplasm by a family of inhibitors, referred to as IκB's. Activation of NF-κB is initiated by signal-induced degradation of IκB, secondary to the activation of IKK. Accordingly, we tested whether Mn activates the NF-κB pathway by IKK activation. As shown in Fig. 2A, Mn increased phosphorylation of IKK, whereas 15 d-PGJ2 almost fully suppressed the Mn-induced activation of IKK. Consistent with these observations, cytosolic IκB was degraded in response to Mn treatment (IκB-α subunit measured by Western blotting), and the Mn (500 µM, 6 h)-induced effect on IκB degradation was fully reversed by 2 h pretreatment with 15 d-PGJ2 (Fig. 2B). There was no statistical difference between the control and the Mn–PGJ2 groups with respect to IκB-α protein expression.

Fig. 2.

15d-PGJ2 inhibits Mn-induced (A) activation of pIKKα/β (phosphorylation of IKK) and (B) IκB degradation in astrocytes. Astrocytes were pretreated for 1 h with 15 d-PGJ2 (10 µM) before 15 min treatment with Mn (500 µM). Cytosolic fractions were immunoblotted for pIKK (86 kDa) (A) and IκB-α (38 kDa) (B). Data are means±SEM (n=4). *p<0.05 compared to the controls, ##p<0.01, ###p<0.001 compared to the matched groups; ***p<0.01, @@@p<0.01 . NS, not significant.

15d-PGJ2 suppresses the Mn-induced activation of the NF-κB pathway

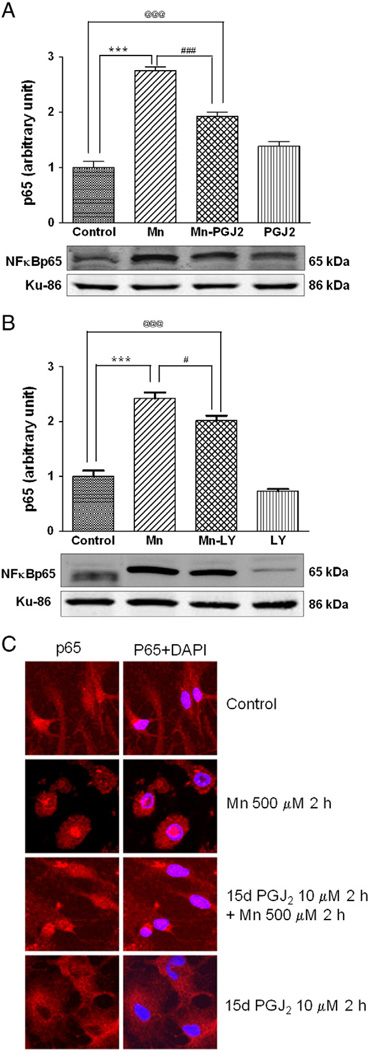

Once activated, NF-κB is translocated into the nucleus where it binds to specific response element consensus sequences, upregulating the transcription of multiple genes, including interleukin-6 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). Accordingly, next we tested if Mn treatment in astrocytes caused the translocation of cytosolic NF-κB to the nucleus. As shown in Fig. 3A, Mn (500 µM, 6 h treatment) increased NF-κB p65 protein levels in the nucleus, and this effect was partially but significantly (p<0.001) reduced by 2 h pretreatment with 15 d-PGJ2 (10 µM). These results were corroborated by cellular staining (Fig. 3C) showing that 2 h pretreatment with 15 d-PGJ2 suppressed the Mn-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB. Inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway with LY29004 (20 µM) only partially blocked the Mn-induced NF-κB translocation (Fig. 3B), indicating that NF-κB nuclear translocation is not regulated solely by PI3K/Akt.

Fig. 3.

15d-PGJ2 reduces Mn-induced activation of NF-κB in astrocytes. NF-κB expression was examined by the detection of the p65 subunit. Astrocytes were pretreated for 2 h with (A) 15 d-PGJ2 (10 µM) or (B) LY29004 (20 µM) before treatment with Mn (500 µM) for 6 h. Nuclear fractions were immunoblotted for the NF-κB p65 subunit. (C) Intracellular localization of NF-κB was examined by the detection of p65 with immunocytochemistry upon treatment with Mn, 15 d-PGJ2, or 15d-PGJ2 plus Mn for the indicated incubation time periods. Data are means±SEM (n=4) (A, B). Imaging sections are representative of six examined sections. ***p<0.001 compared to the controls, #p<0.05, ###p<0.001 compared to the matched groups, @@@p<0.01.

15d-PGJ2 regulates Mn-induced Nrf2 activation

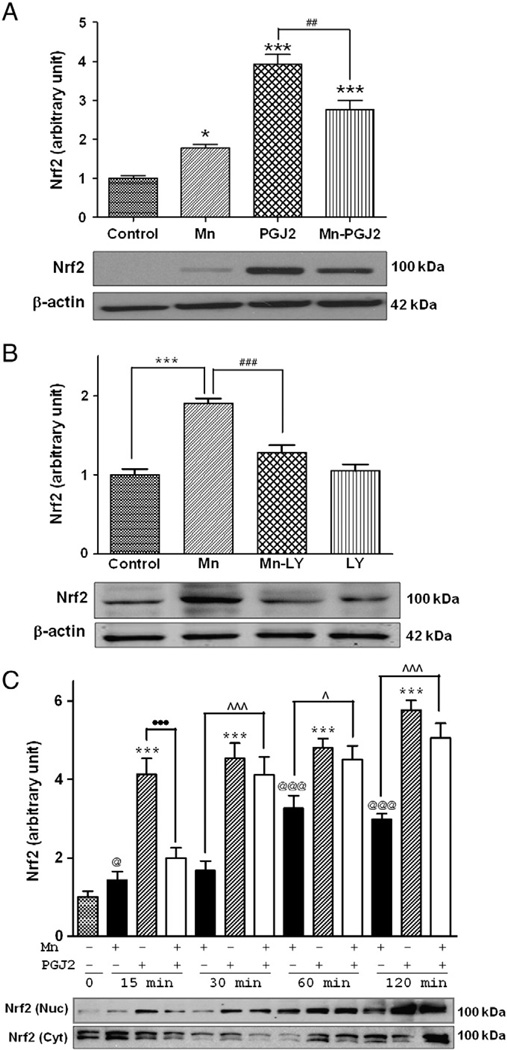

Mn increases the nuclear localization of Nrf2 and its subsequent binding to the ARE, leading to upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and other genes in PC12 cells [38]. Herein, we show that Mn treatment significantly (p<0.05) increased astrocytic Nrf2 protein levels by 77.2% in whole-cell lysates (Fig. 4A); 15 d-PGJ2 had an analogous and more potent effect than Mn alone (p<0.001). Pretreatment (2 h) with 10 µM 15 d-PGJ2 before Mn treatment (6 h), which was in the presence of 15 d-PGJ2, partially suppressed the 15 d-PGJ2-induced increase in Nrf2 protein expression (p<0.01; Fig. 4A). Inhibition of PI3K/Akt with the specific inhibitor LY29004 completely blocked the Mn-induced increase in Nrf2 protein expression in whole-cell lysates (Fig. 4B), indicating that PI3K/Akt activity is required for this effect. Next, we tested whether 15 d-PGJ2 modulates the effect of Mn on Nrf2 nuclear translocation. As shown in Fig. 4C, Mn (500 µM for 2 h) induced a significant (p<0.05) increase in nuclear Nrf2 protein expression. 15 d-PGJ2 also significantly (p<0.001) increased Nrf2 accumulation in the nucleus and the effect was more pronounced than that of Mn treatment alone. Pretreatment (2 h) with 15 d-PGJ2 followed by Mn (2 h) treatment also increased Nrf2 protein accumulation in the nucleus (p<0.001), but the effect was not additive. Whereas the 15 d-PGJ2-induced increase in Nrf2 nuclear accumulation was blocked by 15 min treatment with Mn, this effect was absent upon Mn treatments for ≥30 min. After 30 min treatment, 15 d-PGJ2 potentiated the Mn-induced Nrf2 activation. Nrf2 protein levels in the cytosolic fraction were also analyzed to offer more comprehensive detail. At the early time points coinciding with Mn- and 15 d-PGJ2-induced increases in nuclear Nrf2 (p<0.001), cytosolic Nrf2 levels were significantly reduced (Fig. 4C, p<0.05). However, after 1 h of treatment with 15 d-PGJ2 or Mn, cytosolic Nrf2 proteins levels were indistinguishable from control levels.

Fig. 4.

15d-PGJ2 increases Mn-induced Nrf2 expression in astrocytes. Astrocytes were pretreated with (A) 15 d-PGJ2 (10 µM) for 2 h or (B) LY29004 (20 µM) for 1 h before treatment with Mn (500 µM) for 6 h, followed by Western blot analysis. (C) Time course of Nrf2 protein expression. Astrocytes were pretreated for 2 h with 15 d-PGJ2 (10 µM) before treatment with Mn (500 µM; several time points, up to 120 min). Nuclear and cytosolic fractions were probed for Nrf2 proteins by Western blot analysis. Data are means±SEM (n=4). *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 compared to the controls; ##p<0.01, ###p<0.001 compared to the matched groups; ^p<0.05, ^^^p<0.001; •••p<0.001; @p<0.05, @@@p<0.01.

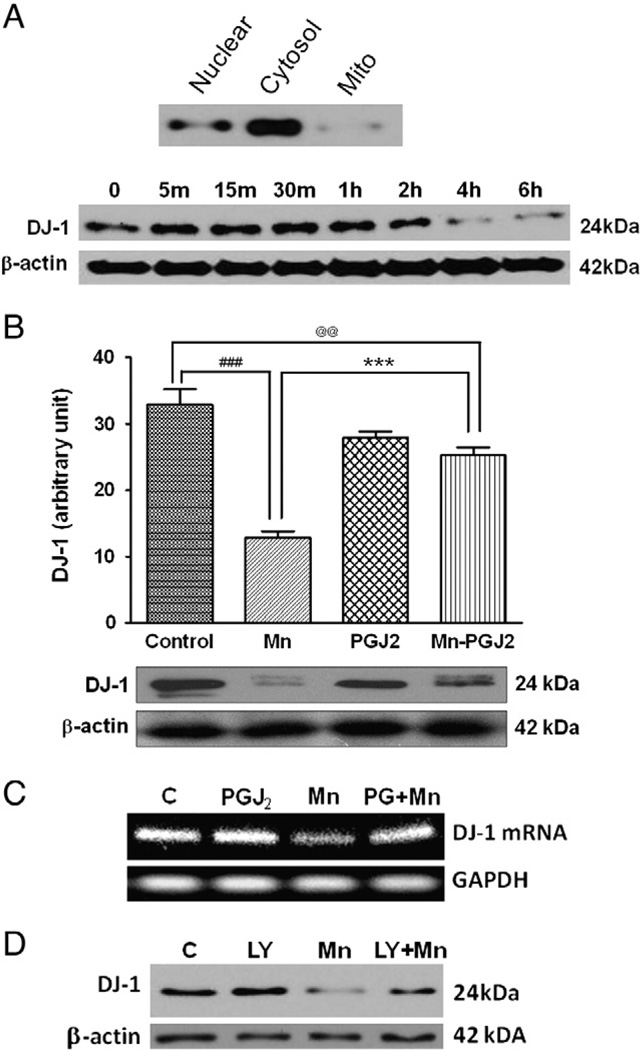

15d-PGJ2 reverses the Mn-induced reduction in DJ-1 expression

Next, we tested whether DJ-1 plays a role in modulating the ability of 15 d-PGJ2 to suppress the Mn-induced effects (see above). DJ-1 is a 189-amino-acid protein that protects cells from oxidative stress [39], but the functional basis of this protection is unclear. DJ-1 is primarily localized in the cytosol and barely detectable in astrocytic mitochondria (Fig. 5A). Mn (500 µM) treatment suppressed DJ-1 expression in astrocytes, with a significant decrease at 4 h, in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). Mn (500 µM) significantly decreased (p<0.001) DJ-1 expression, whereas 15 d-PGJ2 attenuated (p<0.001) the Mn-induced suppression of DJ-1 (Fig. 5B). 15 d-PGJ2 alone did not significantly reduce DJ-1 levels from the control level. Mn-reduced DJ-1 mRNA levels were also reversed by 15 d-PGJ2 pretreatment (Fig. 5C). To determine whether the PI3K signaling pathway is involved in the Mn-reduced DJ-1 expression, astrocytes were pretreated for 1 h before Mn exposure with LY294002. Inhibition of the PI3K pathway attenuated the Mn-reduced DJ-1 expression (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

15d-PGJ2 attenuates Mn-induced inhibition of DJ-1 expression in astrocytes. (A) Top: astrocyte lysates were fractionated into nuclear, cytosolic, and mitochondrial fractions. Bottom: astrocytes were incubated with Mn (500 µM) for various times to analyze DJ-1 protein levels. (B, C) Astrocytes were pretreated for 2 h with 15 d-PGJ2 (10 µM) before Mn (500 µM) exposure for 6 h, followed by (B) Western blot or (C) RT-PCR analyses. (D) Astrocytes were also pretreated for 1 h with LY294002 (20 µM) before Mn (500 µM) exposure for 6 h. Data are means±SEM (B, n=4). ***p<0.001 compared to the controls; ###p<0.001 compared to the matched groups; @@p<0.01.

Discussion

In this study, we show for the first time that 15 d-PGJ2 inhibits Mn-induced NF-κB signaling in rat primary astrocytes by repressing the Mn-induced phosphorylation of IKK. 15 d-PGJ2 also increased astrocytic Nrf2 protein expression in whole lysates as well as its nuclear translocation. Furthermore, 15 d-PGJ2 reversed the Mn-induced decrease in DJ-1 protein expression. These results indicate that 15 d-PGJ2 effectively protects against Mn-induced inflammation and oxidative stress in astrocytes.

The mechanism by which 15 d-PGJ2 blocks the Mn-induced inhibition of IKK phosphorylation and subsequent NF-κB activation has yet to be fully understood. One potential mechanism is covalent binding of 15 d-PGJ2 to the IKKb cysteine residue (Cys179); this reduces the Mn-induced degradation of IκB-α [21]. In addition to binding to IKK, 15 d-PGJ2 may also interact directly with IκB given its ability to bind at the Ser32 site [40]. This mechanism is involved in various in vivo oxidative stress models in which 15 d-PGJ2 has been shown to inhibit NF-κB activation by preventing IκB-α degradation [41]. Whereas 15 d-PGJ2 is a ligand for PPARγ, numerous studies, including this one, suggest that it induces cellular events via PPARγ-independent pathways [23,42]. 15 d-PGJ2 also seems to target Mn-induced activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway because it significantly attenuated the Mn-induced phosphorylation of PI3K (Fig. 1). Mn-induced NF-κB activation could be achieved indirectly by Mn-generated ROS activation of IKK because oxidative stress is considered a general mechanism for NF-κB activation in astrocytes [36]. In addition to inhibiting NF-κB activation, 15 d-PGJ2 might afford its protective effect against Mn toxicity by enhancing Nrf2 protein expression (Fig. 4A). The morphologic change in Mn-treated astrocytes vs control (Fig. 3C) is probably the result of Mn-induced toxicity, such as generation of ROS. There were no changes in cell morphology in the 15 d-PGJ2 plus Mn group or the 15 d-PGJ2 alone group vs controls, consistent with the protective effect of 15 d-PGJ2. 15 d-PGJ2 is also known to block NF-κB inflammatory processes downstream of 15 d-PGJ2-induced Nrf2 activation [43].

Nrf2 probably plays a role in 15 d-PGJ2-induced inhibition of the NF-κB pathway. It has been reported that NF-κB antagonizes Nrf2 by depriving Nrf2 of CREB-binding protein (CBP) [44], indicating that there is cross talk between the NF-κB and the Nrf2 pathways. When 15 d-PGJ2 increases Nrf2 activation, it would deprive NF-κB p65 of CBP, which is required for the activation of the NF-κB pathway, thus resulting in the inhibition of NF-κB activation.

Because Nrf2 induction is an important cellular mechanism for preventing oxidative stress, we examined the effects of 15 d-PGJ2 on Nrf2 expression [45,46]. Upon exposure to Mn, multiple antioxidant genes are upregulated [38]. Consistent with this observation, Mn increased Nrf2 expression (Fig. 4A). Notably, compared with Mn treatment alone, 15 d-PGJ2 was more effective in increasing astrocytic Nrf2 expression (Fig. 4C); yet, a combined treatment with both Mn and 15 d-PGJ2 led to reduced astrocytic Nrf2 protein expression compared with treatment with 15 d-PGJ2 alone. Several cysteine residues on Keap1 are highly reactive and 15 d-PGJ2 is known to directly alkylate Keap1 without dissociating Keap1 from Nrf2, preventing the recruitment of Cul3 ligase and Nrf2 degradation. Keap1 dissociation from Nrf2, in turn, leads to the upregulation of the Nrf2 pathway [47]. A potential mechanism for the seemingly unexpected inhibition by Mn of 15 d-PGJ2-induced Nrf2 activation is that Mn itself can increase Nrf2 expression (Fig. 4A), yet it concomitantly inhibits the covalent binding of 15 d-PGJ2 to Keap1, thus overall attenuating astrocytic Nrf2 activation in the presence of both compounds. Ultimately, concomitant treatment with 15 d-PGJ2 and Mn would potentiate Mn-induced Nrf2 activation, thus strengthening protection against Mn-induced cytotoxicity.

However, a temporal factor must be associated with this effect. The only significant time point at which this antagonism was apparent was the 15-min treatment time point. Notably, Mn antagonism of the PGJ2 effect is absent at 30, 60, and 120 min. The reason for the difference between the 15-min treatment and the other time points remains unclear. One possibility for such discrepancy is that PGJ2 at 30 min causes a maximal activation of Nrf2, such that a ceiling effect is reached, with Mn failing to further potentiate Nrf2 activation.

15 d-PGJ2-induced Nrf2 activation has been shown to modulate multiple cellular functions. It contributes to cytoprotection against oxidative stress by regulating ARE-dependent gene expression [48–50] and against inflammatory processes by activating macrophages [43]. 15 d-PGJ2-induced Nrf2 activation also induces Nrf2-dependent HO-1 and peroxiredoxin 1 expression, which in turn, inhibits inflammatory cytokine TNF-α expression [43].

Mn-induced reduction of DJ-1 expression may represent an alternative pathway by which Mn attenuates the 15 d-PGJ2 induction of Nrf2 protein expression. DJ-1 is known to be a positive regulator of Nrf2 [31]. DJ-1 stabilizes the Nrf2 protein by impairing Keap1-dependent proteasomal degradation of Nrf2 [51]. Our results showed that Mn reduces astrocytic DJ-1 protein as well as mRNA expression, which was readily reversed by 15 d-PGJ2 (Figs. 5B and C). DJ-1 functions as a redox sensitive molecular chaperone [52] and its overexpression protects against oxidative stress-induced toxicity. Conversely, attenuated DJ-1 levels render cells more susceptible to oxidative injury [30]. Because under basal conditions DJ-1 is predominantly localized within the cytosol (Fig. 5A), it might be overexpressed in mitochondria upon stimulation, secondary to oxidative stress, representing a protective mechanism [53]. Indeed, the same authors have localized DJ-1 within both the mitochondrial matrix and the intermembrane space [54], where it maintains mitochondrial integrity and affords protection from oxidant damage [55]. The significant decrease in DJ-1 protein expression upon Mn treatment (Fig. 5) is consistent with the propensity of Mn to preferentially accumulate within mitochondria [56,57]. DJ-1 is also required for Nrf2 activation and its consequent binding to the nuclear ARE and upregulation of antioxidant genes [51]. The PI3K pathway is involved in Mn-induced suppression of DJ-1 because the PI3K pathway inhibitor (LY294002) abolished Mn's effect on DJ-1 suppression. Notably, the reduced DJ-1 protein expression in Mn-treated astrocytes is consistent with observations of increased ROS levels upon treatment with this metal [38]. Mn activates the PI3K pathway in various cell types, including microglia [59], thus modulating a diverse array of cellular functions. For example, in microglia, Mn induces iNOS by the PI3K pathway. Mn induces oxidative stress, which in turn causes cleavage of DJ-1 [60]. Thus, Mn-induced oxidative stress and the ensuing decrease in DJ-1 expression may be mediated by activation of the PI3K pathway.

The 15 d-PGJ2-induced activation of the Nrf2 pathway in astrocytes may play a central role in mediating neuroprotective effects. For example, Nrf2-mediated neuronal protection against MPTP correlates with astrocytic Nrf2 activation [58]. Moreover, expression of astrocytic Nrf2 suppresses microglial function, suggesting that microglial activation and the ensuing neuroinflammation is secondary to astrocyte dysfunction [58].

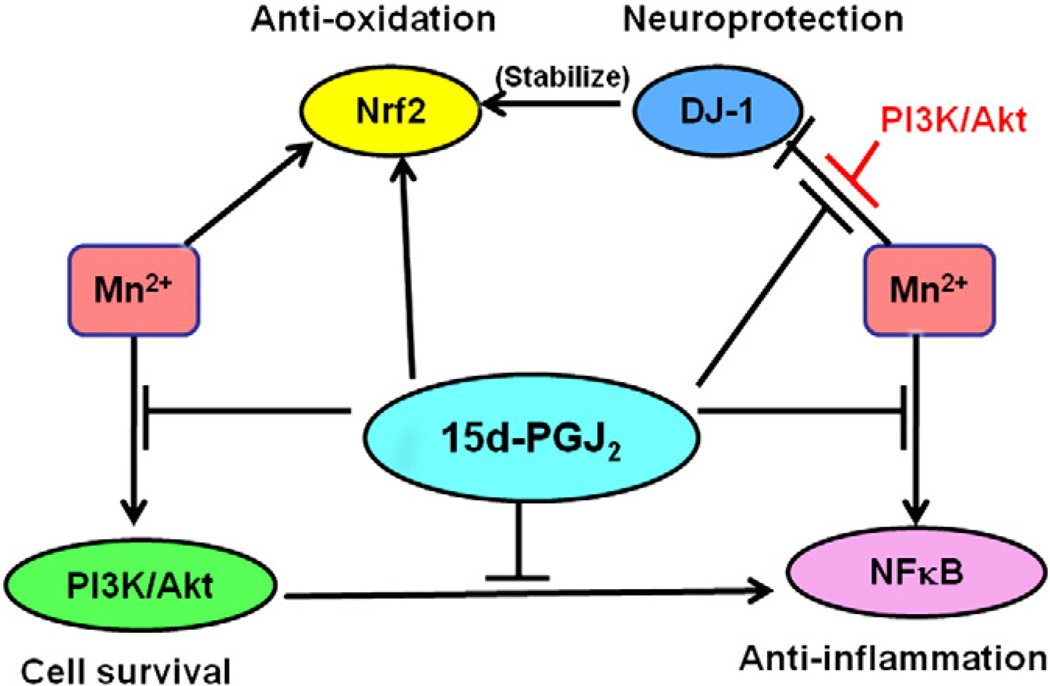

Taken together, results presented herein suggest that 15 d-PGJ2 protects against Mn-induced cellular toxicity via multiple pathways in astrocytes (as diagrammed in Fig. 6). 15 d-PGJ2 inhibits PI3K/Akt activation (Fig. 1), which is associated with NF-κB activation, promoting cell survival. 15 d-PGJ2 also suppresses NF-κB activation by blocking Mn-induced phosphorylation of IKK (Fig. 2). 15 d-PGJ2-induced Nrf2 activation (Fig. 4) and the resulting transcriptional upregulation of antioxidant-related genes represents an additional important mechanism in conferring a measure of cytoprotection. Given that DJ-1 is necessary for transcriptional function and stability of Nrf2, a further mechanism of neuroprotection, including the PI3K pathway, invokes the ability of 15 d-PGJ2 to reverse the Mn-induced reduction in DJ-1 expression (Fig. 5).

Fig. 6.

Proposed mechanisms for 15 d-PGJ2 modulation of Mn-induced cytotoxicity. 15 d-PGJ2 modulates several cellular pathways in response to Mn treatment: it inhibits PI3K/Akt activation, suppresses NF-κB activation by blocking the phosphorylation of IKK, enhances Nrf2 activation in response to Mn-induced oxidative stress, and reverses the Mn-induced attenuation of DJ-1 expression.

Mn preferentially accumulates in astrocytes, where it causes inflammation as well as PI3K/Akt and NF-κB activation [36]. Although 15 d-PGJ2 did not completely abolish the Mn-induced inflammatory effects via the aforementioned pathways, indicating there might be other pathways involved, it effectively afforded significant protection against Mn toxicity. The efficacy of 15 d-PGJ2 in attenuating Mn-induced neurotoxicity is noteworthy as it affords a putative target for mediating neuroprotection. Various mechanisms including Nrf2, NF-κB, DJ-1, and PI3K appear to be involved in Mn-induced neurotoxicity and the protective effect by 15 d-PGJ2 (Fig. 6). Our results suggest that 15 d-PGJ2 could be targeted as a novel therapeutic modality to protect against neurotoxicity in a plethora of other neurotoxic and/or neurodegenerative disorders. Our findings are limited by the lack of dose–response and acute vs chronic exposure assays and a relatively high in vitro dose (500 µM). Nevertheless, they form the basis for additional experimentation in vivo to shed further information on the potential for PGJ2 to afford neuroprotection. Future studies should be carried out in animal models of neurodegeneration to further characterize 15 d-PGJ2's efficacy in attenuating ROS generation and inflammation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anton Webb and Brenya Griffin for technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ES R01 10563 to M.A.).

References

- 1.Carl GF, Blackwell LK, Barnett FC, Thompson LA, Rissinger CJ, Olin KL, Critchfield JW, Keen CL, Gallagher BB. Manganese and epilepsy: brain glutamine synthetase and liver arginase activities in genetically epilepsy prone and chronically seizured rats. Epilepsia. 1993;34:441–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takeda A. Manganese action in brain function. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2003;41:79–87. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mergler D, Baldwin M, Belanger S, Larribe F, Beuter A, Bowler R, Panisset M, Edwards R, de Geoffroy A, Sassine MP, Hudnell K. Manganese neurotoxicity, a continuum of dysfunction: results from a community based study. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:327–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen CJ, Liao SL. Oxidative stress involved in astrocytic alterations induced by manganese. Exp. Neurol. 2002;175:216–225. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CJ, Ou YC, Lin SY, Liao SL, Chen SY, Chen JH. Manganese modulates pro-inflammatory gene expression in activated glia. Neurochem. Int. 2006;49:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stokes AH, Lewis DY, Lash LH, Jerome WG, III, Grant KW, Aschner M, Vrana KE. Dopamine toxicity in neuroblastoma cells: role of glutathione depletion by L-BSO and apoptosis. Brain Res. 2000;858:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barhoumi R, Faske J, Liu X, Tjalkens RB. Manganese potentiates lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of NOS2 in C6 glioma cells through mitochondrial-dependent activation of nuclear factor κB. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2004;122:167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Filipov NM, Seegal RF, Lawrence DA. Manganese potentiates in vitro production of proinflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide by microglia through a nuclear factor κB-dependent mechanism. Toxicol. Sci. 2005;84:139–148. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spranger M, Schwab S, Desiderato S, Bonmann E, Krieger D, Fandrey J. Manganese augments nitric oxide synthesis in murine astrocytes: a new pathogenetic mechanism in manganism? Exp. Neurol. 1998;149:277–283. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294:1871–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith WL. The eicosanoids and their biochemical mechanisms of action. Biochem. J. 1989;259:315–324. doi: 10.1042/bj2590315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scher JU, Pillinger MH. 15d-PGJ2: the anti-inflammatory prostaglandin? Clin. Immunol. 2005;114:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Straus DS, Glass CK. Cyclopentenone prostaglandins: new insights on biological activities and cellular targets. Med. Res. Rev. 2001;21:185–210. doi: 10.1002/med.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uchida K, Shibata T. 15-Deoxy-Δ(12,14)-prostaglandin J2: an electrophilic trigger of cellular responses. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008;21:138–144. doi: 10.1021/tx700177j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajakariar R, Hilliard M, Lawrence T, Trivedi S, Colville-Nash P, Bellingan G, Fitzgerald D, Yaqoob MM, Gilroy DW. Hematopoietic prostaglandin D2 synthase controls the onset and resolution of acute inflammation through PGD2 and 15-deoxyΔ12 14 PGJ2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:20979–20984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707394104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forman BM, Tontonoz P, Chen J, Brun RP, Spiegelman BM, Evans RM. 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPAR γ. Cell. 1995;83:803–812. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kliewer SA, Lenhard JM, Willson TM, Patel I, Morris DC, Lehmann JM. A prostaglandin J2 metabolite binds peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and promotes adipocyte differentiation. Cell. 1995;83:813–819. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Negishi M, Katoh H. Cyclopentenone prostaglandin receptors. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;68–69:611–617. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giri S, Rattan R, Singh AK, Singh I. The 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 inhibits the inflammatory response in primary rat astrocytes via down-regulating multiple steps in phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–Akt–NF-κB–p300 pathway independent of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. J. Immunol. 2004;173:5196–5208. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cernuda-Morollon E, Pineda-Molina E, Canada FJ, Perez-Sala D. 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 inhibition of NF-κB–DNA binding through covalent modification of the p50 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:35530–35536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104518200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rossi A, Kapahi P, Natoli G, Takahashi T, Chen Y, Karin M, Santoro MG. Anti-inflammatory cyclopentenone prostaglandins are direct inhibitors of IκB kinase. Nature. 2000;403:103–108. doi: 10.1038/47520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vunta H, Davis F, Palempalli UD, Bhat D, Arner RJ, Thompson JT, Peterson DG, Reddy CC, Prabhu KS. The anti-inflammatory effects of seleniumare mediated through 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:17964–17973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703075200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hilliard M, Frohnert C, Spillner C, Marcone S, Nath A, Lampe T, Fitzgerald DJ, Kehlenbach RH. The anti-inflammatory prostaglandin 15-deoxy-Δ(12,14)-PGJ2 inhibits CRM1-dependent nuclear protein export. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:22202–22210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.131821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dinkova-Kostova AT, Holtzclaw WD, Cole RN, Itoh K, Wakabayashi N, Katoh Y, Yamamoto M, Talalay P. Direct evidence that sulfhydryl groups of Keap1 are the sensors regulating induction of phase 2 enzymes that protect against carcinogens and oxidants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:11908–11913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172398899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itoh K, Wakabayashi N, Katoh Y, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Engel JD, Yamamoto M. Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes Dev. 1999;13:76–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim EH, Surh YJ. 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 as a potential endogenous regulator of redox-sensitive transcription factors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006;72:1516–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X, Lu L, Dixon C, Wilmer W, Song H, Chen X, Rovin BH. Stress protein activation by the cyclopentenone prostaglandin 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 in human mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2004;65:798–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonifati V, Rizzu P, van Baren MJ, Schaap O, Breedveld GJ, Krieger E, Dekker MC, Squitieri F, Ibanez P, Joosse M, van Dongen JW, Vanacore N, van Swieten JC, Brice A, Meco G, van Duijn CM, Oostra BA, Heutink P. Mutations in the DJ-1 gene associated with autosomal recessive early-onset parkinsonism. Science. 2003;299:256–259. doi: 10.1126/science.1077209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kahle PJ, Waak J, Gasser T. DJ-1 and prevention of oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease and other age-related disorders. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;47:1354–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taira T, Saito Y, Niki T, Iguchi-Ariga SM, Takahashi K, Ariga H. DJ-1 has a role in antioxidative stress to prevent cell death. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:213–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clements CM, McNally RS, Conti BJ, Mak TW, Ting JP. DJ-1, a cancer- and Parkinson's disease-associated protein, stabilizes the antioxidant transcriptional master regulator Nrf2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:15091–15096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607260103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aschner M, Gannon M, Kimelberg HK. Manganese uptake and efflux in cultured rat astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 1992;58:730–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdul-Ghani R, Serra V, Gyorffy B, Jurchott K, Solf A, Dietel M, Schafer R. The PI3K inhibitor LY294002 blocks drug export from resistant colon carcinoma cells overexpressing MRP1. Oncogene. 2006;25:1743–1752. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki Y, Mouri T, Nishiyama K, Fujii N. Study of subacute toxicity of manganese dioxide in monkeys. Tokushima J. Exp. Med. 1975;22:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee ES, Sidoryk M, Jiang H, Yin Z, Aschner M. Estrogen and tamoxifen reverse manganese-induced glutamate transporter impairment in astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 2009;110:530–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liao SL, Ou YC, Chen SY, Chiang AN, Chen CJ. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 expression by manganese in cultured astrocytes. Neurochem. Int. 2007;50:905–915. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baeuerle PA, Baichwal VR. NF-κB as a frequent target for immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory molecules. Adv. Immunol. 1997;65:111–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, Wu S, Shi N, Lian S, Lin W. Nrf2/HO-1 pathway activation by manganese is associated with reactive oxygen species and ubiquitin–proteasome pathway, not MAPKs signaling. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2011;31:690–697. doi: 10.1002/jat.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inberg A, Linial M. Protection of pancreatic β-cells from various stress conditions is mediated by DJ-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:25686–25698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.109751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castrillo A, Diaz-Guerra MJ, Hortelano S, Martin-Sanz P, Bosca L. Inhibition of IκB kinase and IκB phosphorylation by 15-deoxy-Δ(12,14)-prostaglandin J(2) in activated murine macrophages. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:1692–1698. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1692-1698.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia-Bueno B, Madrigal JL, Lizasoain I, Moro MA, Lorenzo P, Leza JC. The anti-inflammatory prostaglandin 15d-PGJ2 decreases oxidative/nitrosative mediators in brain after acute stress in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2005;180:513–522. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin TH, Tang CH, Wu K, Fong YC, Yang RS, Fu WM. 15-Deoxy-Δ(12,14)-prostaglandin-J2 and ciglitazone inhibit TNF-α-induced matrix metalloproteinase 13 production via the antagonism of NF-κB activation in human synovial fibroblasts. J. Cell. Physiol. 2011;226:3242–3250. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Itoh K, Tong KI, Yamamoto M. Molecular mechanism activating Nrf2–Keap1 pathway in regulation of adaptive response to electrophiles. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004;36:1208–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.02.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu GH, Qu J, Shen X. NF-κB/p65 antagonizes Nrf2–ARE pathway by depriving CBP from Nrf2 and facilitating recruitment of HDAC3 to MafK. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1783:713–727. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McEwen BS. Stress, adaptation, and disease: allostasis and allostatic load. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1998;840:33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanaka N, Ikeda Y, Ohta Y, Deguchi K, Tian F, Shang J, Matsuura T, Abe K. Expression of Keap1–Nrf2 system and antioxidative proteins in mouse brain after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. Brain Res. 2011;1370:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kobayashi M, Yamamoto M. Nrf2–Keap1 regulation of cellular defense mechanisms against electrophiles and reactive oxygen species. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 2006;46:113–140. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ishii T, Itoh K, Takahashi S, Sato H, Yanagawa T, Katoh Y, Bannai S, Yamamoto M. Transcription factor Nrf2 coordinately regulates a group of oxidative stress-inducible genes in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:16023–16029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.21.16023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prestera T, Zhang Y, Spencer SR, Wilczak CA, Talalay P. The electrophile counterattack response: protection against neoplasia and toxicity. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 1993;33:281–296. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(93)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramos-Gomez M, Kwak MK, Dolan PM, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Talalay P, Kensler TW. Sensitivity to carcinogenesis is increased and chemoprotective efficacy of enzyme inducers is lost in nrf2 transcription factor-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:3410–3415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051618798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Malhotra D, Thimmulappa R, Navas-Acien A, Sandford A, Elliott M, Singh A, Chen L, Zhuang X, Hogg J, Pare P, Tuder RM, Biswal S. Decline in NRF2-regulated antioxidants in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease lungs due to loss of its positive regulator, DJ-1. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008;178:592–604. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-380OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 52.Shendelman S, Jonason A, Martinat C, Leete T, Abeliovich A. DJ-1 is a redoxdependent molecular chaperone that inhibits α-synuclein aggregate formation. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Junn E, Jang WH, Zhao X, Jeong BS, Mouradian MM. Mitochondrial localization of DJ-1 leads to enhanced neuroprotection. J. Neurosci. Res. 2009;87:123–129. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang L, Shimoji M, Thomas B, Moore DJ, Yu SW, Marupudi NI, Torp R, Torgner IA, Ottersen OP, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Mitochondrial localization of the Parkinson's disease related protein DJ-1: implications for pathogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:2063–2073. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sriram K, Lin GX, Jefferson AM, Roberts JR, Wirth O, Hayashi Y, Krajnak KM, Soukup JM, Ghio AJ, Reynolds SH, Castranova V, Munson AE, Antonini JM. Mitochondrial dysfunction and loss of Parkinson's disease-linked proteins contribute to neurotoxicity of manganese-containing welding fumes. FASEB J. 2010;24:4989–5002. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-163964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gavin CE, Gunter KK, Gunter TE. Manganese and calciumefflux kinetics in brain mitochondria: relevance to manganese toxicity. Biochem J. 1990;266:329–334. doi: 10.1042/bj2660329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gunter TE, Miller LM, Gavin CE, Eliseev R, Salter J, Buntinas L, Alexandrov A, Hammond S, Gunter KK. Determination of the oxidation states of manganese in brain, liver, and heart mitochondria. J. Neurochem. 2004;88:266–280. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen PC, Vargas MR, Pani AK, Smeyne RJ, Johnson DA, Kan YW, Johnson JA. Nrf2-mediated neuroprotection in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease: critical role for the astrocyte. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:2933–2938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813361106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bae JH, Jang BC, Suh SI, Ha E, Baik HH, Kim SS, Lee MY, Shin DH. Manganese induces inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression via activation of both MAP kinase and PI3K/Akt pathways in BV2 microglial cells. Neurosci. Lett. 2006;398:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ooe H, Maita C, Maita H, Iguchi-Ariga SM, Ariga H. Specific cleavage of DJ-1 under an oxidative condition. Neurosci. Lett. 2006;406:165–168. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]