Abstract

Background

Most manufacturers of blood glucose monitoring equipment do not give advice regarding the use of their meters and strips onboard aircraft, and some airlines have blood glucose testing equipment in the aircraft cabin medical bag. Previous studies using older blood glucose meters (BGMs) have shown conflicting results on the performance of both glucose oxidase (GOX)- and glucose dehydrogenase (GDH)-based meters at high altitude. The aim of our study was to evaluate the performance of four new-generation BGMs at sea level and at a simulated altitude equivalent to that used in the cabin of commercial aircrafts.

Methodology/Principal Findings

Blood glucose measurements obtained by two GDH and two GOX BGMs at sea level and simulated altitude of 8000 feet in a hypobaric chamber were compared with measurements obtained using a YSI 2300 blood glucose analyzer as a reference method. Spiked venous blood samples of three different glucose levels were used. The accuracy of each meter was determined by calculating percentage error of each meter compared with the YSI reference and was also assessed against standard International Organization for Standardization (ISO) criteria. Clinical accuracy was evaluated using the consensus error grid method. The percentage (standard deviation) error for GDH meters at sea level and altitude was 13.36% (8.83%; for meter 1) and 12.97% (8.03%; for meter 2) with p = .784, and for GOX meters was 5.88% (7.35%; for meter 3) and 7.38% (6.20%; for meter 4) with p = .187.

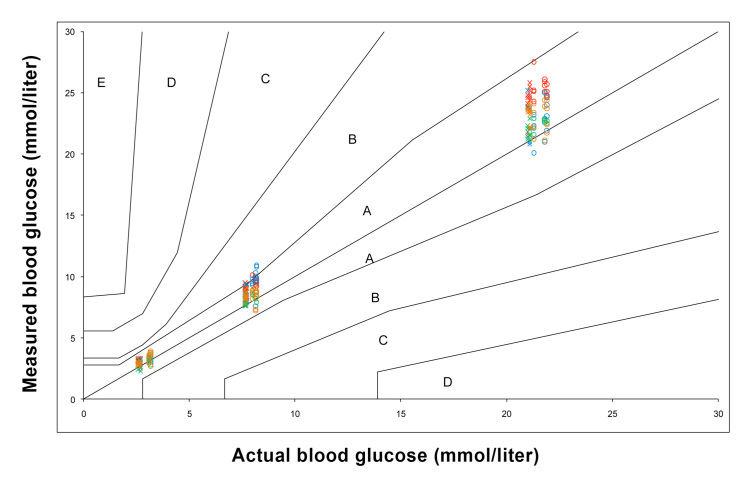

There was variation in the number of time individual meters met the standard ISO criteria ranging from 72–100%. Results from all four meters at both sea level and simulated altitude fell within zones A and B of the consensus error grid, using YSI as the reference.

Conclusions

Overall, at simulated altitude, no differences were observed between the performance of GDH and GOX meters. Overestimation of blood glucose concentration was seen among individual meters evaluated, but none of the results obtained would have resulted in dangerous failure to detect and treat blood glucose errors or in giving treatment that was actually contradictory to that required.

Keywords: altitude, blood glucose meters, diabetes, self-monitoring blood glucose

Introduction

Many national diabetes charities publish guidelines to assist people who have diabetes in their travel plans, and a common recommendation is to take blood glucose monitoring equipment onto the flight rather than stowing it in the luggage hold.1–3 In addition, most manufacturers of blood glucose meters (BGMs) and strips do not advise restricting their use onboard aircraft, and some airlines have blood glucose testing equipment in the aircraft cabin medical bag.4

However, meters utilizing glucose oxidase (GOX)-based enzyme systems can overestimate glucose at high altitudes and/or low temperature, while glucose dehydrogenase (GDH)-based meters can give unpredictable results at altitudes if the test strip is exposed to increased humidity.5 Previous studies using older BGMs, of which some are no longer available on the market, have shown conflicting results on the performance of both GOX- and GDH-based meters at high altitudes.6,7 Two studies conducted by De Mol and colleagues8 and Oberg and Ostenson9 using newer-generation BGMs have come to slightly differing conclusions. The study by Oberg and Ostenson9 showed that GDH meters outperformed a GOX meter only at simulated altitude; however, at real altitude and low temperature, all tested meters performed with similar magnitudes of discrepancy, with the GDH meters showing a within-group variation. The study by De Mol and colleagues,8 on the other hand, showed GDH-based BGMs performing better at real altitude in relation to within-meter variation and accuracy, with no differences observed between GDH- and GOX-based BGMs at simulated altitude of up to 5000 m.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the performance of four new-generation glucose meters at simulated altitude equivalent to that used in the cabin of commercial aircraft.

We hope our study will add to the rather limited knowledge on the accuracy of currently available BGMs at high altitudes. The limitation of our study is that we have not assessed the accuracy of these meters at real altitude and at lower temperatures.

Methods and Design

The study was conducted using a hypobaric chamber provided by the Royal Airforce Base (Henlow, U.K.) to simulate the cabin pressure of commercial airline flights (equivalent to 8000 ft.).10,11

Four BGMs using two different enzyme systems were compared:

OneTouch Ultra Easy (LifeScan Inc.)—GOX

GlucoMen GM (Menarini Diagnostics)—GOX

ACCU-CHEK Aviva (Roche Diagnostics)—GDH

Optium Xceed (Abbott Laboratories Ltd.)—GDH

These systems measure blood glucose by means of an electrochemical reaction, which involves glucose reacting with a reagent, leading to the generation of current proportional to the glucose concentration. All meters used are designed for use with capillary blood. Three of the meters are calibrated against plasma, while the ACCU-CHEK Aviva is calibrated against venous blood. All meters were calibrated as recommended by the manufacturer, and calibration readings were within expected range.

For the purpose of our study, the YSI 2300 Stat Plus analyzer (YSI Life Sciences, Fleet, Hants, UK) was used as the laboratory reference method for glucose measurement and was kept outside the hypobaric chamber throughout the studies. In addition, a Radiometer EML 100 analyzer (Radiometer Ltd., Crawley, U.K.) was placed inside the hypobaric chamber, and samples were analyzed simultaneously with both the YSI reference analyzer and the Radiometer to determine if altitude per se had an effect on blood glucose results obtained.

Venous blood was collected from a healthy volunteer, in lithium heparin tubes, on the day before the study and was allowed to sit overnight for the glucose concentration to fall. Glucose spiking solution (20% in deionized water) was added to aliquots of heparinized whole blood to attain target glucose concentrations in the “hypoglycemic” (3.0–4.0 mmol/liter), “euglycemic” (7–11 mmol/liter), and “hyperglycemic” (19–25 mmol/liter) ranges.

All the samples were evaluated with the four BGMs at sea level under local conditions and at a simulated altitude of 8000 ft. in the hypobaric chamber.

On attaining the desired simulated altitude, 20 min were allowed for the three different blood samples to acclimatize to this altitude and the solutions were mixed by inversion before testing. All the BGMs were recalibrated at a simulated altitude of 8000 ft. Graduated Pasteur pipettes were used to place the test solutions on the meter reagent strips. The test sample’s glucose concentration was measured at regular intervals by both the YSI and the Radiometer analyzers under local barometric pressure to detect the rate of glycolysis with time. Glucose measurements from each meter at sea level and at simulated altitude were compared with those obtained by the reference methods under local barometric pressure.

At both sea level and altitude, for each solution, the test was performed three times by two operators (simultaneously on the YSI and Radiometer) over a period of 25 and 20 min, respectively. The timing was synchronized with the BGM assessment. There was a time lag of approximately 1.5 h between the start of sea level assessment and the altitude assessment.

Statistical Analysis

No sample size estimation was done prior to commencing the study. Using the results found, post hoc calculations indicated that, with the given number of observations in each comparison, the study had a minimum of 83% power to detect differences of at least 7% between the mean percentage errors (PEs) at sea level and altitude [assuming 8% for the common standard deviation (SD) and a two-sided significance level of 0.05].

Statistical analysis assessed agreement between BGM determination of plasma glucose and the reference method at each altitude. The PE of the radiometer readings compared with the YSI readings (using YSI as the gold standard) was also calculated. The accuracy of each meter was determined by calculating the PE of each meter’s readings versus corresponding YSI readings (at the same time, solution, and altitude) and was calculated as

For each of the four meters, mean PE was compared between sea level and altitude using the paired t-test separately for each glucose concentration solution. A similar analysis was carried out with the four meters grouped according to type of enzyme system used (GDH or GOX) to compare PE at sea level and altitude. Each sample was tested in duplicate over three time points by two operators at sea level and at simulated altitude. There was no significant change in results obtained over time, so the data for all three time points were used together in the analyses, and no adjustment for a time factor was made. An analysis of variance was carried out to compare the mean PE between the four meters, separately for each solution at sea level and altitude. Bland–Altman graphs were plotted to determine the agreement between results obtained by the different BGMs and the reference laboratory method, i.e., YSI and Radiometer.

The performance of each meter was assessed against the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) criteria, and clinical accuracy was evaluated using the consensus error grid analysis (EGA).12 The ISO criteria are a standard method of evaluating the accuracy of BGMs. The standard calls for a minimum accuracy—95% of all measured values should fall within 20% of glucose values above 4.2 mmol/liter and 0.83 mmol/liter of glucose values below 4.2 mmol/liter.13

The EGA14 considers the clinical implication of any self-treatment decisions based on estimated blood glucose level. The EGA defines the x axis as the reference blood glucose and the y axis as the value generated by the reference system. The diagonal represents perfect agreement between the two, with data points above and below the diagonal representing overestimates and underestimates, respectively. The grid is divided into five zones of varying degrees of accuracy and inaccuracy of glucose estimation. Values falling into zone A would result in clinically correct treatment decisions, zone B in benign or no treatment, zone C in overcorrection of acceptable blood glucose levels, zone D in dangerous failure to detect and treat blood glucose errors, and zone E in erroneous treatment (i.e., treatment contradictory to that actually required). An EGA was done for each meter compared with the YSI reference method, and results were plotted on a single graph, with points for sea level and altitude shown separately.

Analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics version 18 and Microsoft Office Excel 2007.

Results

We compared the YSI reference method with the performance of the Radiometer for three solutions of different glucose concentration at both sea level and a simulated altitude of 8000 ft.

The differences in the Radiometer readings between sea level and altitude were small and similar to the differences in the YSI readings, suggesting that the Radiometer’s readings are not affected by this altitude (not possible to test differences for significance due to small number of observations) (Table 1). Given the 1.5 h delay between measurements at sea level and simulated altitude, this difference would be consistent with the anticipated fall in glucose over time in an unpreserved blood sample as a result of in vitro glycolysis.15,16

Table 1.

Blood Glucose Values for the Radiometer (inside the Chamber) and YSI (outside the Chamber) Glucose Analyzers

| Hypoglycemia | Euglycemia | Hyperglycemia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 3 observations per category | Radiometer blood glucose values: mean (SD), mmol/liter | ||

| Sea level | 3.83 (0.15) | 10.33 (0.15) | 28.13 (0.23) |

| Simulated altitude 8000 ft. | 3.10 (0.10) | 9.60 (0.10) | 26.97 (0.06) |

| Mean difference (sea level–altitude) | 0.70 | 0.70 | 1.20 |

| YSI blood glucose values: mean (SD), mmol/liter | |||

| Sea level | 3.14 (0.05) | 8.09 (0.10) | 21.67 (0.32) |

| Simulated altitude 8000 ft. | 2.62 (0.06) | 7.67 (0.03) | 21.07 (0.06) |

| Mean difference (sea level–altitude) | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.60 |

Combining results from all three solutions gives the mean (SD) PE for GDH meters at sea level and altitude as 13.36% (8.83%) and 12.97% (8.03%), respectively, a mean difference of 0.38% (p = .784), when compared with the YSI. For GOX meters, the mean (SD) PE at sea level and altitude were 5.88% (7.35%) and 7.38% (6.20%), respectively, a mean difference of -1.50% (p = .187). The mean (SD) percentage error for the GDH and GOX meters at sea level and altitude compared to the YSI for each solution is shown above in Table 2.

Table 2.

Percentage Error for Both Glucose Dehydrogenase and Both Glucose Oxidase Meters Compared with the YSI Reference for the Different Glucose Concentrations at Sea Level and Altitude

| Hypoglycemia | Euglycemia | Hyperglycemia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 24 observations per category | GDH meters: PE (mean[SD]), % | ||

| Sea level | 11.44 (8.04) | 17.93 (8.18) | 10.69 (8.73) |

| Altitude | 12.45 (10.09) | 14.45 (6.72) | 12.01 (6.98) |

| Mean difference (sea level–altitude) | -1.01 | 3.48 | -1.31 |

| p value (sea level versus altitude) | 0.704 | 0.115 | 0.568 |

| GOX meters: PE (mean[SD]), % | |||

| Sea level | 7.70 (10.31) | 4.74 (5.99) | 5.20 (4.36) |

| Altitude | 8.21 (8.51) | 7.12 (4.94) | 6.82 (4.55) |

| Mean difference (sea level–altitude) | -0.50 | -2.38 | -1.63 |

| p value (sea level versus altitude) | 0.855 | 0.140 | 0.212 |

An analysis of variance was carried out to compare the PEs with the YSI between the meters separately for each solution at sea level and altitude. This showed that, with the exception of solution 1 (i.e., hypoglycemic sample) at sea level (p = .116), there was a highly statistically significant difference between the four meters in terms of their PE for all other combinations of solution and sea level/altitude (p < .001 for all comparisons). The percentage error for each meter compared to the YSI at sea level and altitude for the difference glucose concentration is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Percentage Error for Each of the Four Glucose Meters Compared with the YSI for the Different Glucose Concentrations at Sea Level and Altitude

| Hypoglycemia | Euglycemia | Hyperglycemia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 12 observations per category | ACCU-CHEK Aviva: PE (mean[SD]), % | ||

| Sea level | 13.84 (6.11) | 16.77 (4.88) | 17.33 (4.39) |

| Altitude | 19.77 (4.18) | 17.72 (3.16) | 16.97 (2.84) |

| Mean difference (sea level–altitude) | -5.92 | -0.95 | 0.36 |

| p value (sea level versus altitude) | 0.011 | 0.577 | 0.812 |

| Optium Xceed: PE (mean[SD]), % | |||

| Sea level | 9.04 (9.24) | 19.10 (10.64) | 4.06 (6.62) |

| Altitude | 5.13 (8.86) | 11.19 (7.82) | 7.04 (6.32) |

| Mean difference (sea level–altitude) | 3.91 | 7.90 | -2.99 |

| p value (sea level versus altitude) | 0.302 | 0.050 | 0.271 |

| OneTouch Ultra Easy: PE (mean[SD]), % | |||

| Sea level | 4.78 (8.39) | 5.04 (3.61) | 3.89 (1.48) |

| Altitude | 8.05 (10.49) | 4.34 (3.62) | 3.56 (2.51) |

| Mean difference (sea level–altitude) | -3.27 | 0.70 | 0.33 |

| p value (sea level versus altitude) | 0.408 | 0.639 | 0.700 |

| GlucoMen GM: PE (mean[SD]), % | |||

| Sea level | 10.63 (11.54) | 4.43 (7.86) | 6.50 (5.82) |

| Altitude | 8.36 (6.43) | 9.89 (4.59) | 10.09 (3.71) |

| Mean difference (sea level–altitude) | 2.27 | -5.46 | -3.58 |

| p value (sea level versus altitude) | 0.558 | 0.050 | 0.086 |

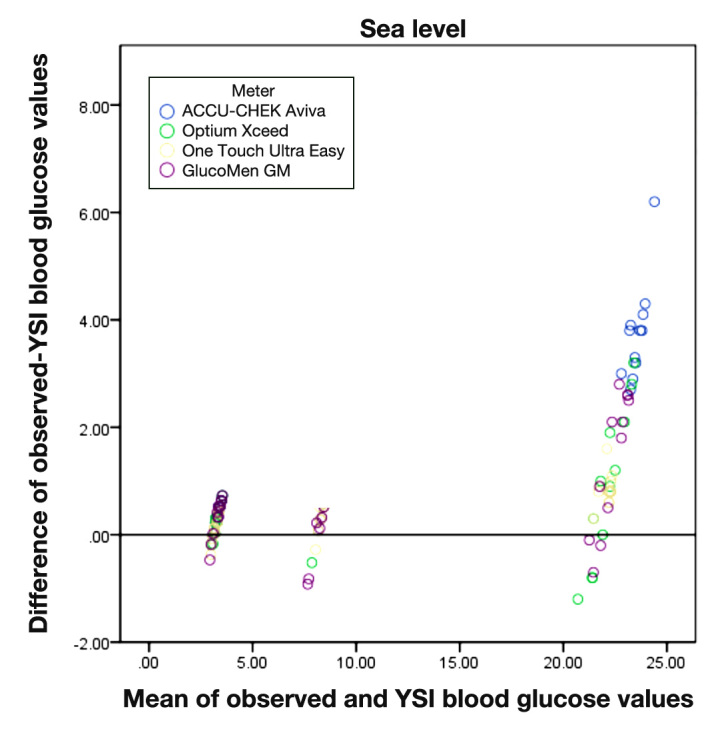

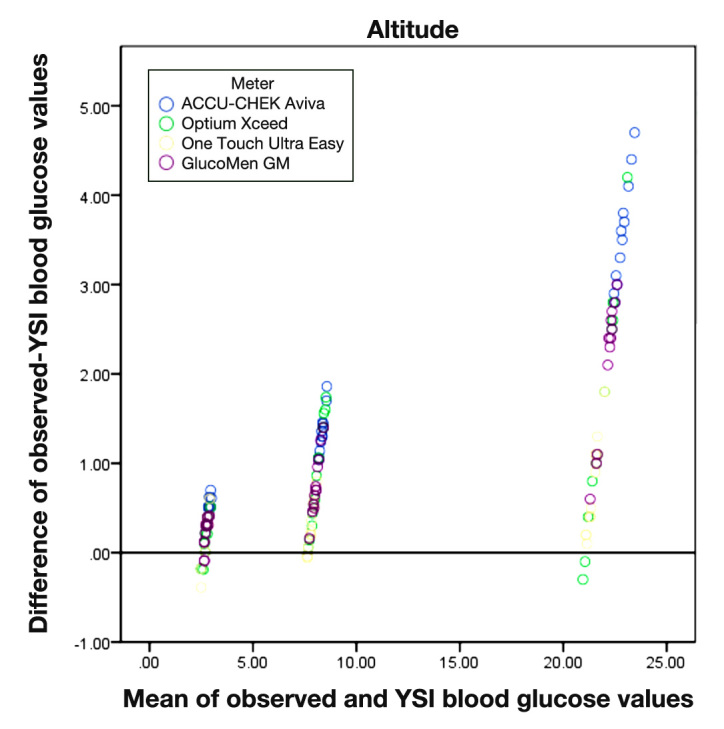

The size of difference between the readings from each meter and the YSI is positively correlated with the size of measurement (i.e., larger absolute differences with larger average readings (p < .001 for all correlation coefficients) (Figures 1 and 2). All the meters overestimated readings of glucose concentration compared with the YSI.

Figure 1.

Bland–Altman graph for each meter compared with the YSI.

Figure 2.

Bland-Altman graph for each meter compared with the YSI at 8,000 feet altitude.

International Organization for Standardization Criteria

The ACCU-CHEK Aviva BGM fulfilled the ISO criteria for readings at sea level and almost fulfilled the criteria at simulated altitude. The GlucoMen GM BGM fulfilled these criteria with blood glucose concentrations obtained at simulated altitude only. The Optium Xceed and the OneTouch Ultra Easy did not meet the criteria, as only approximately 72% of the results obtained at sea level and 87% and 80%, respectively, of those obtained at simulated altitude were within the defined criteria (Table 4).

Table 4.

Percentage of Blood Glucose Meter Results Meeting ISO 15197 Criteria

| Meter | Sea level | Altitude |

|---|---|---|

| ACCU-CHEK Aviva | 95.8% | 94.4% |

| Optium Xceed | 72.2% | 87.5% |

| OneTouch Ultra Easy | 72.2% | 80.5% |

| GlucoMen GM | 75% | 100% |

Consensus Error Grid Analysis

All results obtained from the four glucose meters at both sea level and simulated altitude fell within zones A and B of the consensus error grid, using YSI as the reference (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Consensus EGA for all 4 glucose meters compared with YSI. Red, ACCU-CHEK Aviva; blue, Optium Xceed; green, OneTouch Ultra Easy; orange, GlucoMen GM; circles, sea level; crosses, simulated altitude.

Discussion

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has indicated that there is a requirement for BGMs to deliver enhanced performance in terms of (1) better analytical performance, (2) better clinical performance, (3) better adherence to human factors that can effect accuracy, as well as (4) better labeling of interfering substances.17 Implicit in these suggestions is a drive to better performance of self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) systems in specific clinical situations.

Studies assessing the accuracy of BGMs at altitude have been conducted in the past, with conflicting results. Some studies, such as ours, were conducted at simulated altitude in a hypobaric chamber,6,8,9 while others were conducted during mountaineering expeditions.7–9 Older-generation BGMs, which are no longer commercially available, were used in some studies.6,7

The results obtained from our study are similar to those of a study by De Mol and colleagues8 that was conducted in a hypobaric chamber at simulated altitude and also at real altitude. The simulated altitude arm showed a trend of overestimation of blood glucose levels by both GDH- and GOX-based blood glucose monitoring systems under hypobaric conditions in comparison with normobaric conditions. Our findings are somewhat similar to those of Oberg and Ostenson,9 where five meters (four GDH and one GOX) were evaluated in a hypobaric chamber. Three of the GDH-based meters (Precision Xtra, ACCU-CHEK Compact, and FreeStyle) overestimated blood glucose levels at altitude in comparison with sea level at both normal and high blood glucose ranges, although the overestimation was less in the GDH meters in comparison with the GOX system, i.e., OneTouch Ultra.

Our findings are in contrast to those of Gautier and associates,6 who showed underestimation of blood glucose concentration at low barometric pressure and under hypoxic conditions in a hypobaric chamber in three out of the five meters evaluated. In that study, however, the ACCU-CHEK Easy meter significantly overestimated BGM readings at altitude whereas the OneTouch II also showed a trend of overestimation but was not of statistical significance. An earlier study assessed the performance of seven blood glucose testing systems at high altitude at a diabetes camp and also demonstrated underestimation of whole blood glucose concentration in six of the meters, but most of the results obtained were in the error grid “safe zones,” i.e., zones A and B.7

The supposition is that GDH-based meters are more accurate at higher altitudes, as these systems are not affected by the reduced oxygen availability at this level. Accuracy and precision of BGMs have been shown to be affected by altitude, temperature, and relative humidity. Kenneth and coworkers18 demonstrated an underestimation of blood glucose by 1–2% for each 1000 ft. gain in altitude using seven commonly available BGMs during a mountaineering expedition. They also demonstrated that the effect of altitude on BGM precision was less significant when temperature and relative humidity were adjusted for.

By comparison, we found that none of the results obtained by either the GDH-based or the GOX-based BGMs assessed were significantly affected by a simulated altitude of 8000 ft., although all meters overestimated glucose concentration compared with the YSI reference at both sea level and altitude.

Both the Radiometer and the YSI analyzers utilize a GOX-based enzymatic reaction. Here, the results obtained with the Radiometer were not significantly affected by altitude, and as previously mentioned, the 2.5% reduction in results obtained at altitude is consistent with the effect of in vitro glycolysis, as the sea level assessment was conducted prior to altitude assessment.

Manufacturers of both GDH-based meters recommend use at altitudes of up to 3094 m (10,150 ft.) and 2195m (7200 ft.) for ACCU-CHEK Aviva and Optium Xceed, respectively. Both OneTouch Ultra Easy and GlucoMen GM are recommended for use at altitudes of up to 3048 m (10,000 ft.). Our altitude testing was conducted at a simulated altitude of 8000 ft., which is the adjusted in-flight cabin pressure of most commercial air flights. At altitude, there is reduced partial pressure of oxygen, with reduced oxygen availability, and the assumption is that GOX test strips, being sensitive to oxygen concentration, may over-estimate capillary glucose concentration in comparison with GDH-based systems.

Using the ISO criteria to compare our results with our validated laboratory method, ACCU-CHEK Aviva appeared to be the best performing of all meters assessed at both sea level and altitude, as almost all the results obtained with this meter were within the predefined criteria for performance of BGM. Caution must be taken in interpreting this data, as the overall numbers of samples tested were small, and a single failure represents a relatively large percentage.

Of more relevance is the practical application or consequences of acting on the results obtained from the different meters. Error grid analysis assigns a specific level of clinical risk to any possible SMBG error. Despite the intermeter and intrameter variability of the meters, when the consensus EGA was applied, none of the results obtained at sea level or simulated altitude by the different meters fell within higher clinical risk zones C, D, or E. There would be no overcorrection of acceptable blood glucose levels, dangerous failure to detect and treat blood glucose errors, or treatment contradictory to that actually required. This shows that there are no clinically significant differences between the different meters, and they are all acceptable for decision making and clinical use at altitude.

Although the latest-generation BGMs are highly accurate, caution still needs to be exercised when these meters are used at higher altitudes.

Conclusions

The findings of this small study indicate that the meters tested give a clinically satisfactory performance in conditions simulating commercial airline flight and that patients can be reassured with regard to their operation and performance.

It is important, however, that diabetes specialists educate people with diabetes, who engage in altitude-related activities and air travel, on how environmental factors as well as other factors can affect the performance of meters, and if necessary, give guidance on what type of meter to use under such conditions. Other factors that would limit potential for errors such as proper techniques should also be emphasized.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. Joan Parkes for providing the coordinates for the consensus EGA used and to Jo Haviland the statistician. We would also like to thank RAF, Henlow, UK for the use of the Hypobaric Chamber

Glossary

- (BGM)

blood glucose meter

- (EGA)

error grid analysis

- (GDH)

glucose dehydrogenase

- (GOX)

glucose oxidase

- (ISO)

International Organization for Standardization

- (PE)

percentage error

- (SD)

standard deviation

- (SMBG)

self-monitoring of blood glucose

Disclosures

David Kerr has received consultancy fees, research support, and honoraria from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diabetes Care, manufacturers of blood glucose monitoring systems.

References

- 1.Diabetes UK Air travel and insulin. http://www.diabetes.org.uk/Guide-to-diabetes/Living_with_diabetes/Travel/Air_travel_and_insulin/#equip. Accessed June 22, 2012.

- 2.Chandran M, Edelman SV. Have insulin, will fly: diabetes management during air travel and time zone adjustment strategies. Clin Diabetes. 2003;21(2):82–85. [Google Scholar]

- 3.FitForTravel; NHS Scotland Diabetes mellitus and travel. www.fitfortravel.scot.nhs.uk/advice/advice-for-travellers/diabetes.aspx. Accessed July 12, 2011.

- 4.VoyageMD Tips for a safe journey. http://www.voyagemd.com/diabetes-travel-tips/. Accessed June 22, 2012.

- 5.Piepmeier EH, Jr, Hammett-Stabler C, Price ME, Kemper GB, Davis MG., Jr Atmospheric pressure effects on glucose monitoring devices. Diabetes Care. 1995;18(3):423–424. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.3.423b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gautier JF, Bigard AX, Douce P, Duvallet A, Cathelineau G. Influence of simulated altitude on the performance of five blood glucose meters. Diabetes Care. 1996;19(12):1430–1433. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.12.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giordano BP, Thrash W, Hollenbaugh L, Dube WP, Hodges C, Swain A, Banion CR, Klingensmith GJ. Performance of seven blood glucose testing systems at high altitude. Diabetes Educ. 1989;15(5):444–448. doi: 10.1177/014572178901500515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Mol P, Krabbe HG, de Vries ST, Fokkert MJ, Dikkeschei BD, Rienks R, Bilo KM, Bilo HJ. Accuracy of handheld blood glucose meters at high altitude. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e15485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oberg D, Ostenson CG. Performance of glucose dehydrogenase-and glucose oxidase-based blood glucose meters at high altitude and low temperature. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(5):1261. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Civil Aviation Authority . CAP 393 air navigation: the order and the regulations. London: Civil Aviation Authority; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Federal Aviation Administration. FAR code of US federal regulations. Parts 25, 121, and 125. Washington DC: US Department of Transportation; 2004.

- 12.Parkes JL, Slatin SL, Pardo S, Ginsberg BH. A new consensus error grid to evaluate the clinical significance of inaccuracies in the measurement of blood glucose. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(8):1143–1148. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.8.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. International Organization for Standardization. ISO 15197:2003. In vitro diagnostic test systems -- requirements for blood-glucose monitoring systems for self-testing in managing diabetes mellitus.

- 14.Clarke WL, Cox D, Gonder-Frederick LA, Carter W, Pohl SL. Evaluating clinical accuracy of systems for self-monitoring of blood glucose. Diabetes Care. 1987;10(5):622–628. doi: 10.2337/diacare.10.5.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Pasqua A, Mattock MB, Phillips R, Keen H. Errors in blood glucose determination. Lancet. 1984;2(8412):1165. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91611-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikesh LM, Bruns DE. Stabilization of glucose in blood specimens: mechanism of delay in fluoride inhibition of glycolysis. Clin Chem. 2008;54(5):930–932. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klonoff DC. The Food and Drug Administration is now preparing to establish tighter performance requirements for blood glucose monitors. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4(3):499–504. doi: 10.1177/193229681000400301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fink KS, Christensen DB, Ellsworth A. Effect of high altitude on blood glucose meter performance. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2002;4(5):627–635. doi: 10.1089/152091502320798259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]