Abstract

Objective

Biomarkers for preterm labor and delivery can be discovered through the analysis of the transcriptome (transcriptomics) and protein composition (proteomics). Characterization of the global changes in low molecular weight compounds which constitute the “metabolic network” of cells (metabolome) is now possible by using a “metabolomics” approach. Metabolomic profiling has special advantages over transcriptomics and proteomics since the metabolic network is downstream from gene expression and protein synthesis, and thus more closely reflects cell activity at a functional level. This study was conducted to determine if metabolomic profiling of the amniotic fluid can identify women with spontaneous preterm labor (PTL) at risk for preterm delivery, regardless of the presence or absence of intra-amniotic infection/inflammation (IAI).

Study Design

Two retrospective cross-sectional studies were conducted, including 3 groups of pregnant women with spontaneous PTL and intact membranes: 1) PTL who delivered at term; 2) PTL without IAI who delivered preterm; and 3) PTL with IAI who delivered preterm. The first was an exploratory study that included 16, 19 and 20 patients in groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively. The second study included 40, 33 and 40 patients in groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Amniotic fluid metabolic profiling was performed by combining chemical separation (with gas and liquid chromatography) and mass spectrometry. Compounds were identified by using authentic standards. The data were analyzed using Discriminant Analysis for the first study and Random Forest for the second.

Results

1) In the first study, metabolomic profiling of the amniotic fluid was able to identify patients as belonging to the correct clinical group with an overall 96.3% (53/55) accuracy; 15 of 16 patients with PTL who delivered at term were correctly classified; all patients with PTL without IAI who delivered preterm neonates were correctly identified as such (19/19), while 19/20 patients with PTL and IAI were correctly classified. 2) In the second study, metabolomic profiling was able to identify patients as belonging to the correct clinical group with an accuracy of 88.5% (100/113); 39 of 40 patients with PTL who delivered at term were correctly classified; 29 of 33 patients with PTL without IAI who delivered preterm neonates were correctly classified. Among patients with PTL and IAI, 32/40 were correctly classified. The metabolites responsible for the classification of patients in different clinical groups were identified. A preliminary draft of the human amniotic fluid metabolome was generated and found to contain products of the intermediate metabolism of mammalian cells as well as xenobiotic compounds (e.g. bacterial products and Salicylamide).

Conclusion

Among patients with spontaneous PTL with intact membranes, metabolic profiling of the amniotic fluid can be used to assess the risk of preterm delivery in the presence or absence of infection/inflammation.

Keywords: preterm labor, preterm delivery, intra-amniotic inflammation, pregnancy, amniocentesis, microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity, MIAC, cytokines, chorioamnionitis, high-dimensional biology, “omics” sciences, intraamniotic infection

INTRODUCTION

Preterm parturition is one of the “Great Obstetrical Syndromes”. This term was coined to indicate that obstetrical disorders have: 1) multiple etiologies; 2) a long preclinical phase; 3) frequent fetal involvement; 4) be adaptive in nature; and 5) be the result of gene-environment interactions. [1–4] Progress in the understanding of the causes of preterm labor has relied on hypothesis-driven research. [5–73] This approach has yielded important information. However, the development of high-dimensional biology promises to provide a comprehensive description of the biological processes in complex diseases such as the preterm parturition syndrome[4,74,75] and identify biomarkers with prognostic and diagnostic implications, which may be more difficult to identify using a reductionist approach.

High-dimensional biology refers to the use of high throughput techniques which allow simultaneous examination of changes in the genome (DNA), transcriptome (mRNA), proteome (proteins), lipidome (lipids) and other biochemical components in a biological sample with the goal of understanding the physiology or mechanisms of disease. [76–78] The term “ome” refers to an abstract entity, group of mass, while “omics” sciences refer to the study of entities in aggregate. [79,80] Such techniques have included genomics, [81–85] transcriptomics, [86–88] proteomics, [89,90] and lipidomics, [91–93] and their fundamental principle is that a complex system can be understood more completely by considering its entirety, allowing for a global description of changes in biological samples.

Metabolites, which have small molecular weights, are part of primary and intermediate metabolism, and are estimated to be represented by more than 2,000 compounds in the human metabolome, [94–97] which refers to the catalog of those molecules in a specific organism or compartment, such as human metabolome, plasma metabolome, or amniotic fluid metabolome. Metabolomics is the study of the repertoire of non-proteinaceous, small molecules present in an organ, tissue or fluid. [98] Like other “omics” sciences, this discovery-based approach does not require a specific hypothesis and it is presumably unbiased in nature. So far, examination of the cervico-vaginal and amniotic fluid proteome has been employed in order to identify biomarkers for spontaneous preterm labor. [99–110] The objective of this study was to determine, for the first time, if amniotic fluid metabolic profiling could be used to identify women with preterm labor and intact membranes at risk for preterm delivery, regardless of the microbial and inflammatory state of the amniotic cavity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population

We conducted a cross-sectional study by searching our clinical database and bank of biological samples to identify patients admitted to the hospital with the diagnosis of spontaneous preterm labor (PTL) with intact membranes, and that underwent amniocentesis for the assessment of the microbial state of the amniotic cavity and/or fetal lung maturity. Inclusion criteria included: 1) singleton gestation; 2) gestational age between 22–35 weeks; 3) live fetus; 4) intact membranes; and 5) signed informed consent approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Sotero del Rio Hospital (an affiliate of the Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, Chile,) or Wayne State University (Detroit, Michigan, USA) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS. Women with multiple pregnancies as well as those with fetal chromosomal and/or congenital anomalies were excluded.

This study was conducted in two phases and included patients divided in 3 groups: 1) PTL who subsequently had a delivery at term; 2) PTL without IAI who delivered preterm; and 3) PTL with IAI who delivered preterm. The first study included 16 pregnant women with PTL who delivered at term, 19 women with PTL without IAI who delivered preterm, and 20 patients with PTL and IAI. The second study included 40 pregnant women with PTL who delivered at term, 33 women with PTL without IAI who delivered preterm, and 40 patients with PTL and IAI.

Definitions

Spontaneous preterm labor was defined by the presence of regular uterine contractions occurring at a frequency of at least two every 10 minutes associated with cervical change before 37 completed weeks of gestation that required hospitalization. Preterm delivery was defined as birth before 37 weeks of gestation. Intra-amniotic infection was defined as a positive amniotic fluid culture for microorganisms. For the purpose of the first study, intra-amniotic inflammation was defined as an amniotic fluid white blood cell (WBC) count >100 cells/mm3, [111,112] while for the second study, intra-amniotic inflammation was defined as an amniotic fluid interleukin (IL)-6 concentration >2.6 ng/mL. [113]

Sample collection

Amniotic fluid samples were obtained from transabdominal amniocentesis performed for evaluation of microbial status of the amniotic cavity and/or assessment of fetal lung maturity in patients approaching term. Samples of amniotic fluid were transported to the laboratory in a sterile capped syringe and cultured for aerobic/anaerobic bacteria and genital mycoplasmas. White blood cell count, glucose concentration and Gram-stain were also performed in the amniotic fluid shortly after collection as previously described. [112,114,115] The results of these tests were used for clinical management. Amniotic fluid IL-6 concentrations were used only for research purposes. Amniotic fluid not required for clinical assessment was centrifuged at 1,300 g for 10 minutes at 4°C and the supernatant was aliquoted and stored at −80°C until analysis. Many of these samples have been previously used to study the biology of inflammation, hemostasis, and growth factor concentrations in normal pregnant women and those with pregnancy complications.

Metabolomics methodology

Randomization of samples

amniotic fluid samples (n=168) were coded with a unique identifier for subsequent handling, and these identifiers were associated with a random number so that laboratory staff was blinded to the clinical diagnosis (including studies 1 and 2). The samples were processed in ascending order of their random numbers in two sets of samples. All samples were bar-coded throughout and received new barcodes at each step.

Extraction and preparation

The samples were removed from a −80° freezer and placed on ice to thaw. A 550 μl aliquot of pooled amniotic fluid (control sample) was placed on ice as well. A 100 μl aliquot of each sample was placed in individual wells of a 96-well deep-well plate, as were three 100 μl aliquots of the control sample and three 100 μl volumes of water (for blank controls). The sample placement was randomized and controlled by a platform-wide LIMS. Using a method described by Andreoli et al., [116] a 400 μl volume of EtOAc/EtOH (1:1) was added to each sample and mixed on a Hamilton Star liquid-handling robot (Hamilton, Inc. Reno, NV, USA). The samples were transferred to a filter plate and a vacuum applied. Subsequent rinse solvents were similarly applied at 200 μl each (MeOH, MeOH/H2O (3:1), and DCM/MeOH (1:1), respectively). The resulting pooled extract was divided into two equal parts for LC/MS and GC/MS, respectively. Samples were concentrated on a Labconco Centrivap Concentrator 7810000, prior to lyophilization in a Labconco Freezone 6 lyophilizer (both Labconco Corp., Kansas City, MO, USA). The remaining samples were returned to a −80° freezer. Samples to be analyzed by liquid chromatography were re-dissolved in a 40% aquous ethanolic solution, while samples to be analyzed using gas chromatography were derivatized according to the procedure described by Gehrke and Leimer. [117] All samples had a final volume of 100 μl.

Mass spectroscopy and data processing

Samples subjected to LC/MS were analyzed on a Thermo-Finnigan LTQ-FT, a hybrid ion trap-Fourier transform mass spectrometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Inc. Waltham, MA, USA). The ion trap mass spectrometer (ITMS) and Fouier transform mass spectometry (FTMS) units were run at resolutions of 1,500 and 50,000, respectively, and tuned daily for these resolutions. Each sample carried a set of internal standards which were used to validate the performance of the procedures. An ITMS was scanned from 80 to 800 m/z, and FTMS analyzed from 200 to 2,000 m/z. A 10 μl aliquot of the re-dissolved extract was injected into the solvent path of a Perflourophenyl (PFP) column. The non-linear elution gradient began at water [0.1% formic acid (FA)] to 100% methanol (0.1% FA) at 7.5 minutes and ultimately to 100% acetone (0.1% FA) at 15 minutes. The column was re-equilibrated for 10 minutes before the next injection.

The samples were analyzed by GC/MS on a Thermo-Finnigan Mat95 (Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA, USA) coupled to an Ultra-Trace high resolution Gas Chromatograph (the Mat95 was tuned to a resolution of 10,000, and mass accuracy checked against the 131 ion of Perfluorokerosene) daily. The chromatographic conditions were non-linear on a RTX-5-sil column. The temperatures ranged from 60° to 340° C. A 1 μl aliquot of the derivatized extract was injected into a split/splitless injector (kept at 240° C) run in splitless mode. Each sample carried a set of internal standards which were used to validate procedural parameters.

The data analysis was chemocentric; therefore, the resulting data streams were processed to identify as many compounds as could be seen by the Metabolyzer software. [118] All identified peaks had a signal-to-noise ratio of >6, and an area of >50,000 ions. All named compounds were compared to authentic compounds. Compounds seen with regularity, but for which no standard was available, were assigned unique identifiers. Quantitation was relative to internal standards specific to each data stream. Data analyzed included both relative and normalized (Z-score) concentration. The identification of Mass spectral peaks for both the LC and GC platforms was accomplished by comparison to authentic standards.

Data mining

Metabolomic profiles in the amniotic fluid were defined as the sets of biochemical compounds and their concentrations that best distinguish PTL patients in one group from the other two groups. Compounds that are significantly high or low in one group could be discovered by algorithms that have been used to build “class predictors”. The class predictors use the concentrations of these informative compounds to distinguish the profiles of PTL patients in one group from profiles of individuals in the other groups. Broadly speaking, this is “supervised learning”, a type of data mining in which a learning algorithm is presented with known “classes” and then attempts to derive a set of rules (a class predictor) that will predict the class membership of new samples. In investigations of this kind, class predictors are typically trained on a random subset of the data, the “training set”. Our study was conducted in two phases. The first set included 16 women with PTL who delivered at term, 19 women with PTL without IAI who delivered preterm, and 20 patients with PTL and IAI. The second set included 40 women with PTL who delivered at term, 33 women with PTL without IAI who delivered preterm, and 40 patients with PTL and IAI. This allowed us to rigorously assess the degree to which the class predictors have captured signatures that truly distinguish the different PTL groups. We used three approaches to class prediction: partial least square discriminate analysis (PLS-DA), relative class association/weighted voting, and scatter analysis.

Statistical analysis

Linear discriminant function analysis, which constructs linear separation boundaries, was used to explore the relationship between the metabolomic profile of amniotic fluid and clinical classification of patients for study #1. Random Forest, a classification tree-based algorithm, was used for the analysis of study #2. Single classification tree method is useful for selecting from a small collection of predictor variables those that best explain a phenotype. Some of the features of this technique are: 1) ease of interpretation; 2) flexibility for the inclusion of interactions among predictors; and 3) ability to handle heterogeneity among samples. Classification trees use all variables and relevant cases when creating nodes in a single tree that represents the outcome of the learning process. However, single classification tree algorithms may easily over-fit data in the presence of a large number of predictor variables.

Alternatively, Random Forest builds a large number of classification trees, each grown using a subset of a bootstrap sample, while the remaining are left out for prediction. Each bootstrap sample was drawn randomly and of the same size from the original data with replacement. The variables used for splitting nodes in a tree are randomly chosen, much smaller sub-samples of the complete set of variables. The introduced double randomness (bootstrap sample and variable selection) and internal validation ultimately leads to an unbiased estimation of misclassification error. Over-fitting in presence of a large number of variables can be therefore avoided. Importantly, random Forest calculates importance scores which estimate the importance of a variable by looking at how much node impurities or prediction accuracy decreases when data for that variable are permuted while all other data are left unchanged. The Importance Score is a useful tool that organizes the metabolites according to the degree of contribution in classifying the cases into well-defined clinical phenotypes. Importance Scores are used to prioritize the variables in this model, and this information is used to determine the patterns that are informative with respect to the phenotype, creating a classification for each case. The results of classification are compared with actual clinical statuses. As the result of this process, matrices (true-negative, false-positive, true-positive, and false-negative) are created showing the number of patients classified properly. Classification accuracy is calculated as the proportion of total of correct classifications (number of true-negative and true-positive classifications).

In this study, the three classes were preterm labor and delivery with and without IAI, and preterm labor delivered at term.. Rpackage “randomForest”[119] was applied to classify the three classes based on metabolomic profiling.

Gini Index calculation

The variable importance calculation depends slightly upon the specific algorithm used to split nodes in growing a trees in Random Forest. A splitting rule takes all the cases at a particular node in a decision tree and divides those cases so that some go to the left branch and others go to the right branch. There are a very large number of possible splitting rules – one for each explanatory variable and every possible split-point for that variable. At each node in the current tree, Classification and Regression Trees (CART) does a computer-intensive search to find the particular splitting rule that most helps in the classification of the cases. Our analysis used the Gini impurity criterion to determine the best splitting rule at each (non-terminal) node in the tree, because of its fast but generally robust performance in classification problems. Alternative rules include the entropy criterion and the misclassification rate (see Brienan for a comparative study). [120] The rules are usually consistent with each other. Gini criterion seeks the split such that the cases that go to the left are mostly of one category (or a small set of categories), while the cases that go to the right are mostly of another category (or small set of other categories). One says that the best split maximally reduces the “impurity” at that node. In Random Forest, this splitting process continues until all of the cases in a node have the same classification, and thus the node is “pure”.

There are many possible measures of impurity. The most widely used Gini index at a node t is:

where there are k different categories among the cases at node t, and Pj is the proportion of cases in the node belonging to category j. CART searches among all the possible splits that divide cases in a parent node t into a left and right child nodes to find the one that maximizes

where PL is the proportion of cases assigned to the left child node, PR is the proportion of cases assigned to the right child node and Φ(t L), Φ(tR) are the Gini indices for the left and right child nodes.

RESULTS

Tables 1 and 2 display the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients included in the first and second study, respectively. Microorganisms isolated from the amniotic fluid in the first and second study are presented in Table 3.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population (First study).

| Term Delivery (n=16) | PTL without IAI (n=19) | PTL with IAI (n=20) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 25 (16 – 38) | 21 (17 – 45) | 31 (19 – 41) |

| Nulliparity | 47 (9/19) | 56 (9/16) | 25 (5/20) |

| Gestational age at amniocentesis (weeks) | 27 (22 – 32) | 28 (23 – 33) | 26 (22 – 33) |

| Cervical dilatation (cm) | 0 (0 – 1) | 1.5 (0 – 5) | 0 (0 – 5) |

| Amniocentesis to delivery interval (days) | 86 (49 – 130) | 1 (0 – 7) | 3 (0 – 7) |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 39 (37 – 42) | 29 (23 – 33) | 27 (22 – 34) |

| Sample storage time (months) | 49 (15 – 73) | 63 (22 – 80) | 33 (8 – 63) |

Values are presented as median (range) of percentage (number)

PTL: preterm labor; IAI: intra-amniotic infection/inflammation

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population (Second study).

| Term Delivery (n=40) | PTL without IAI (n=33) | PTL with IAI (n=40) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 21 (15 – 41) | 22 (14 – 40) | 22 (16 – 41) |

| Nulliparity | 50 (20/40) | 52 (17/33) | 50 (20/40) |

| Gestational age at amniocentesis (weeks) | 31 (24 – 33) | 30 (23 – 33) | 29 (23 – 33) |

| Cervical dilatation (cm) | 0 (0 – 4) | 0 (0 – 5) | 1 (0 – 7) |

| Amniocentesis to delivery interval (days) | 55 (33 – 109) | 5 (0 – 7) | 1 (0 – 7) |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 39 (37 – 41) | 31 (23 – 34) | 29 (23 – 34) |

| Sample storage time (months) | 71 (17 – 83) | 32 (1 – 144) | 57 (4 – 114) |

Values are presented as median (range) of percentage (number)

PTL: preterm labor; IAI: intra-amniotic infection/inflammation

Table 3.

Microorganisms isolated from the amniotic fluid in the first and second study.

| First Study | Second Study |

|---|---|

| Ureaplasma urealyticum | Ureaplasma urealyticum |

| Candida albicans | Candida albicans |

| Fusobacterium sp. | Fusobacterium sp. |

| Listeria monocytogenes | Escherichia coli |

| Peptostreptococcus sp. | Gardnerella vaginalis |

| Prevotella sp. | Mycoplasma hominis |

| Streptococcus viridans | Streptococus agalactiae |

| Bacteroides sp. | Vellonella sp. |

| Prevotella sp. | |

| Clostridium sp. | |

| Capnocytophaga sp. |

First Study (Exploratory study)

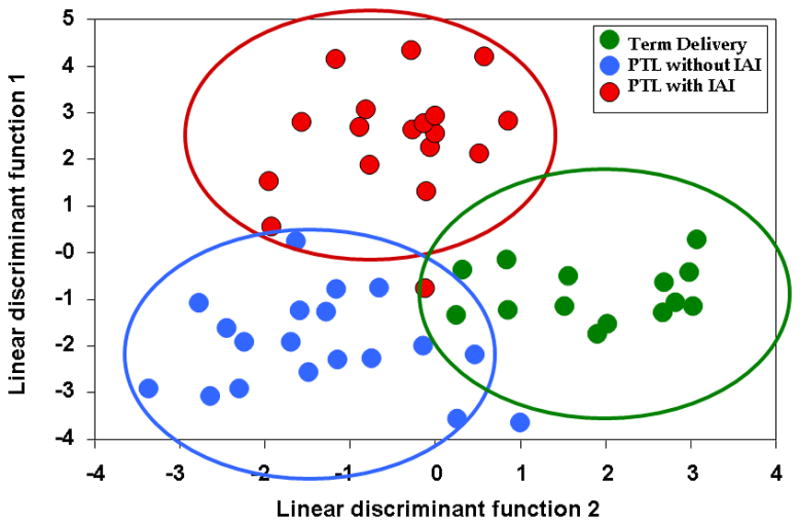

The purpose of the first study was to examine whether the metabolic profile of amniotic fluid could classify patients according to phenotype. A supervised analysis with the results of the metabolic profiling of amniotic fluid using linear discriminant function analysis was conducted. The results displayed in Figure 1 show that the technique (metabolomics) had promise to classify patients into the three groups. Table 4 displays the classification of patients according to their metabolomic profile. The accuracy of classification was 96.36% (53/55). Recognizing that this excellent diagnostic performance could have been due to over-fitting, we conducted a second study in an independent and larger set of samples using more robust-to-overfitting method to identify metabolomes separating the three groups.

Figure 1.

Supervised analysis for classification of patients according to their metabolic profile of amniotic fluid. In green, patients who presented with preterm labor but delivered at term; in blue, those with preterm labor who delivered preterm without intra-amniotic inflammation and in red, those with intra-amniotic inflammation. (PTL – preterm labor; IAI – intra-amniotic infection/inflammation)

Table 4.

Prediction of the Clinical Class According to the Amniotic Fluid Metabolic Profile (First study; supervised).

| Predicted Class | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True Class | PTL Term Delivery | PTL without IAI | PTL with IAI | |

| PTL Term delivery | 15 | 1 | 0 | |

| PTL without IAI | 0 | 19 | 0 | |

| PTL with IAI | 0 | 1 | 19 | |

Data are presented as number.

PTL: preterm labor; IAI: intra-amniotic infection/inflammation

Second Study (Validation study)

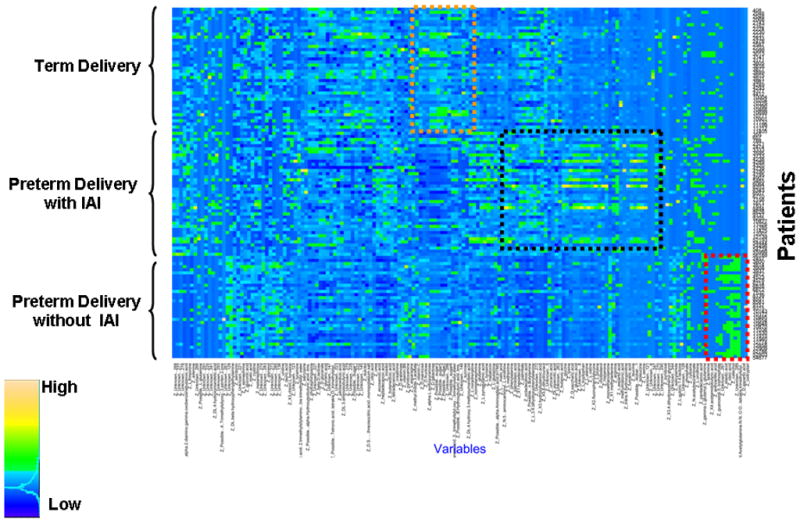

Figure 2 shows the raw data of the second study in a heatmap, in which every single row represents a metabolic “fingerprint” of a particular patient. A cursory inspection of the graph displays differences among groups. Tables 5, 6 and 7 display the differentially expressed metabolites in the amniotic fluid of patients with PTL who delivered at term, PTL without IAI who delivered preterm, and that of those with PTL with IAI, respectively. Random Forest analysis of the metabolic profiling of the amniotic fluid accurately predicted 39 of 40 patients who delivered at term and 29 of 33 patients who delivered preterm without IAI. However, it performed less well in patients with preterm delivery with IAI (32 out of 40). The overall accuracy for prediction of clinical classes was 88.5% (100/113) (Table 8). To identify the metabolites that contributed to the separation of the groups, we calculated the Gini index (Table 9).

Figure 2.

Each horizontal line is a fingerprint of the metabolomic profile of amniotic fluid in an individual patient. Each vertical line represents the concentration of a metabolite in amniotic fluid. The color scale provides an index of abundance. Three patient groups are included in the study (see left column), and the metabolic fingerprinting characterizing each group is within a colored box. (IAI – intra-amniotic infection/inflammation)

Table 5.

Differentially regulated metabolites in patients with PTL who delivered at term (Second study).

| Increase | Decrease | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | Others | Amino Acids | Others |

| Galactose | Urea | Alanine | Possible heptanedioic acid |

| Hexose cluster 5 | 3-hydroxybutanoic acid | Glutamine | Possible alpha aminoadipic acid |

| Hexose cluster 3 | Unknown 286 | Pyroglutamic acid | Pentanedioic acid |

| Mannose | Palmitate | Isoleucine | Normetanephrine |

| Hexose cluster 2 | Threo-isocitric acid | Glutamic acid | Unknown 8 |

| Hexose cluster 6 | Glycerol | Serine | Unknown 121 |

| Fructose | Citric acid | Tyrosine | Unknown 221 |

Table 6.

Differentially regulated metabolites in patients with PTL without IAI who delivered preterm (Second study).

| Increase | Decrease | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | Others | Amino Acids | Carbohydrates | Others |

| Hexose cluster 6 | Urocanic acid | Alanine | Galactose | Urea |

| Dulcitol | Possible N-Acetyl glutamine | Pyroglutamic acid | Hexose cluster 5 | 3-hydroxybutanoic acid |

| 1-methyladenine | Proline | Hexose cluster 3 | Palmitate | |

| Butanoic acid | Glycine | Mannose | Octadecanoic acid | |

| Beta hydroxyphenylethyamine | Glutamine | Inositol | Butanedioic acid | |

| Vitamin B6 | ||||

| Salicylamide | ||||

| Oleic acid | ||||

| Unknown 128 | ||||

| Unknown 276 | ||||

| Unknown 285 | ||||

| Unknown 283 | ||||

| Unknown 123 | ||||

| Unknown 344 | ||||

Table 7.

Differentially regulated metabolites in patients with PTL with IAI (Second study).

| Increase | Decrease | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acids | Others | Carbohydrates | Others |

| Alanine | Palmitate | Galactose | Glycerol |

| Pyroglutamic acid | Urea | Hexose cluster 3 | Gluconic acid |

| Glutamine | Inositol | Hexose cluster 5 | Threo-isocitric acid |

| Leucine | Octadecanoic acid | Mannose | Unknown 221 |

| Proline | Possible heptanedioic acid | Hexose cluster 6 | Unknown 286 |

| Isoleucine | Possible alpha aminoadipic acid | Hexose cluster 2 | |

| Valine | Possible butanoic acid 3oxy | Hexose cluster1 | |

| Glutamic acid | Butanedioic acid | Fructose | |

| Glycine | Unknow 270 | ||

| Tyrosine | Unknown 8 | ||

| Unknown 121 | |||

Table 8.

Prediction of the Clinical Class According to the Amniotic Fluid Metabolic Profile (Second study).

| Predicted Class | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True Class | PTL Term Delivery | PTL without IAI | PTL with IAI | |

| PTL Term delivery | 39 | 0 | 1 | |

| PTL without IAI | 2 | 29 | 2 | |

| PTL with IAI | 7 | 1 | 32 | |

Data are presented as number.

PTL – preterm labor; IAI – intra-amniotic infection/inflammation

Table 9.

Metabolites Important in Classification Determined by Random Forest (Gini Index) (* - Amino acids; # - carbohydrates)

| Metabolite | Gini Index | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Methyladenine | 3.066 |

| 2 | Heptanedioic acid | 3.005 |

| 3 | N Acetylglutamine* | 2.939 |

| 4 | Beta hydroxyphenylethylamine* | 2.698 |

| 5 | Unknown 128 | 2.389 |

| 6 | Hexose cluster 5# | 1.878 |

| 7 | Hexose cluster 1# | 1.874 |

| 8 | Leucine* | 1.836 |

| 9 | glycerol | 1.729 |

| 10 | Isoleucine* | 1.687 |

| 11 | Inositol# | 1.541 |

| 12 | Methionine* | 1.506 |

| 13 | Glycine* | 1.501 |

| 14 | Galactose# | 1.464 |

| 15 | Hexose cluster 3# | 1.463 |

| 16 | Catechol | 1.442 |

| 17 | Salicylamide | 1.431 |

| 18 | Succinic acid | 1.410 |

| 19 | Unknown 5 | 1.263 |

| 20 | Mannose# | 1.220 |

| 21 | Unknown 8 | 1.217 |

| 22 | Glutamic acid* | 1.130 |

| 23 | Phenylalanine* | 1.104 |

| 24 | Alpha sorbopyranose# | 1.077 |

| 25 | Cholesterol | 1.045 |

| 26 | Unknown 289 | 1.039 |

| 27 | Fructose# | 1.031 |

| 28 | Hexose cluster 2# | 0.995 |

| 29 | Tryptophan* | 0.883 |

| 30 | Eicosanoic acid | 0.816 |

Amino acids;

Carbohydrates

A list of the metabolites identified in study #1 and study #2 is provided as a supplementary table.

DISCUSSION

Principal findings of the study

1) The metabolome of amniotic fluid can be characterized by using parallel techniques; 2) a group of compounds previously identified as part of the human intermediate metabolism were identified in the amniotic fluid. Notably, we also identified compounds that could be considered xenobiotic, such as Salicylamide and bacterial products; 3) the amniotic fluid metabolome can be analyzed for the identification of metabolites differentially expressed in patients with PTL using a combination of liquid chromatography and gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry; 4) metabolomic profiling was able to identify patients as belonging to the correct clinical group with a 88.5% precision (100/113); 5) patients who deliver preterm without IAI have a relative decrease in both carbohydrates and amino acids; and 6) in contrast, those with IAI have a more substantial decrease in compounds in the carbohydrate cluster, and a relative increase in amino acids.

The results of the study reported herein indicate that the presence of IAI is associated with an altered amniotic fluid metabolite composition. Specifically, amniotic fluid of women with IAI contains less carbohydrates and more amino acids compared to patients with PTL who delivered at term. Interestingly, while a decrease in carbohydrates was associated with preterm delivery in the presence or absence of IAI, an increase in amino acid metabolites is a unique feature of PTL with IAI (Table 10). Indeed, carbohydrates such as mannose, galactose and fructose were relatively increased in patients with PTL who delivered at term, but decreased in patients with PTL and IAI. The opposite was true with amniotic fluid amino acids. A decrease in alanine, glutamine and glutamic acid was noted in patients with PTL who delivered at term, while all of these amino acids were increased in the presence of IAI.

Table 10.

Relative abundance of carbohydrate and amino acids in the study groups.

| Carbohydrates | Amino Acids | |

|---|---|---|

| PTL Term delivery | ↑ | ↓ |

| PTL without IAI | ↓ | ↓ |

| PTL with IAI | ↓↓ | ↑ |

The cross-sectional nature of our studies does not allow us to infer a causal or a temporal relationship between alterations in amniotic fluid metabolites and IAI. In addition, it is not clear what the specific source of each metabolite is. Fetal urine is a major contributor of amniotic fluid and both amnion cells and amniotic fluid WBC secrete their metabolites into the amniotic cavity. Nevertheless, a possible explanation for the shift from carbohydrate-rich to amino-acid-predominant metabolites could be a fetal catabolic state associated with a fetal systemic response syndrome (FIRS). [121–126] Catabolic states are associated with an increased demand for carbohydrates and decreased protein synthesis. This, in turn, can affect plasma and urine concentrations of these metabolites. Indeed, early neonatal sepsis (within 48 hours from delivery) in preterm neonates born to mothers with chorioamnionitis is characterized by an increased demand for carbohydrates. [127] Likewise, term neonates with infection have a higher consumption rate of carbohydrates than non-infected term newborns that can not be reconciled by changes in caloric intake. [128–130] The increase in amniotic fluid amino acids further supports the hypothesis that fetal infection and/or inflammation induces a catabolic state. Sepsis is associated with changes in metabolism that result in net proteolysis and negative nitrogen balance. [131,132] Of interest, both non-essential (e.g. alanine, glutamate) and essential (e.g. isoleucine) amino acids were included among the differentially expressed metabolites among patients with and without IAI. The latter finding is of special importance since the source of the essential amino acids in amniotic fluid should be the maternal circulation. The increase in the amniotic fluid concentration of amino acids in patients with PTL and IAI may reflect either changes in maternal availability of these amino acids or altered placental-amino acid transport. [133]

An additional explanation for the changes in metabolite content of amniotic fluid in patients with PTL and IAI relates to the presence of bacteria in the amniotic cavity. Utilization of carbohydrates as nutrients by bacteria may result in decreased concentrations of these molecules. Several lines of evidence support this view: 1) a low amniotic fluid glucose concentration is a well-established biomarker of IAI. [134–137] Low glucose concentrations are also associated with microbial invasion of other biological fluids including cerebrospinal[138,139] and synovial fluid;[140] 2) Fusobacterium species contain a galactose-binding protein, and it is possible that this protein may contribute to the decrease concentrations of galactose in infected amniotic fluid;[141] 3) Ureaplasmal lipoglycans are constituted primarily of mannose, glucose, and galactose, [142] suggesting that these carbohydrates may be consumed with the replication of this microorganism in the amniotic fluid; and 4) glucose is also required as a fuel by activated neutrophils engaged in the process of microbial phagocytosis and killing. [143]

Methyladenine was the most important classifier as determined by Random Forest analysis (Gini Index). N6-methyl-adenine (m6A) is found in the genomes of many fungi, bacteria and protists, [144] as well as in archaeal DNA. [145] N6-methyl-adenine is involved in many fundamental bacterial cell processes including: 1) bacterial defense against bacteriophages and transposons; 2) regulation of chromosome replication, chromosome segregation, and reorganization of the nucleoid after DNA replication; 3) DNA-strand discrimination for mismatch repair; 4) regulation of conjugal transfer of plasmids; 5) packaging of phage DNA into capsids; and 6) transcriptional regulation of fimbrial operons and other virulence genes. [146] This is the first study to report the detection of methyladenine in amniotic fluid. Tavazzi et al. [147] used the highly sensitive, ion-pairing High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) method with UV detection to identify several purines, pyrimidines, amino acids and other molecules in amniotic fluid of 10 normal pregnant women. Despite the high sensitivity of HPLC, methyladenine was not detected. It is possible that the presence of methyladenine in amniotic fluid is due to bacterial destruction. This explanation can account for the importance of this metabolite in the classification of the study groups, as well as for the negative results reported by Tavazzi et al. [147] in normal pregnant women.

The second most important metabolite in the classification of the study groups was heptanedioic acid, also know as pimelic acid. [148] Diamino pimelic acid (DAP) is a component of the bacterial cell-wall. Specifically, DAP is a key cross-linking constituent of the peptidoglycan layer. Most bacteria require either lysine or its biosynthetic precursor, DAP, as a component of the peptidoglycan layer of the cell wall. [149] Importantly, mammals do not produce or utilize DAP and require L-lysine as a dietary component. These observations led to the hypothesis that inhibitors of the DAP biosynthetic pathway would not be expected to show mammalian toxicity and made the biosynthesis of L-lysine via DAP as a target for naturally occurring antibiotics. [150–152] Recently, a DAP residue [γ-D-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid (iE-DAP)] was identified as the minimal structure in cell wall peptidoglycan capable of stimulating Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain protein 1 (NOD1, an important component of the innate immune system). [153] iE-DAP is known to exist only in particular bacteria including common Gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, and several Gram-positive bacteria, such as Listeria monocytogenes. [154] Of note, both Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes were identified in the amniotic fluid of patients in our study. Consistent with this, IL-6 production by folliculostellate cells in the normal pituitary gland is stimulated by diamino pimelic acid. It is tempting to postulate that this metabolite is released to the amniotic cavity following the destruction of bacterial cell-wall.

Several metabolites that have been shown to have a prognostic value for the diagnosis of IAI and/or preterm labor such as prostaglandins[155–163] and leukotrienes[164–166], were not identified as differentially expressed in the present study. Low concentrations of these metabolites, their biochemical diversity, as well as extraction method that is not optimized for these compounds, can account for this limitation. This issue needs to be addressed with an additional analytical platform, such as specifically optimized lipidomics, to cover a broad range of metabolites.

Metabolomics in pregnancy

High-dimensional biology techniques have been used to study normal pregnancy and parturition, as well as pregnancy complications, largely through the application of genomics, [167–176] transcriptomics[177–198] and proteomics. [99,101,105,107,152,199–232] Yet, few studies have reported the use of metabolomics in reproduction and pregnancy complications. It has been proposed that metabolomics may play an important role in the management of male infertility[233] as well as in assisted reproductive technology; indeed, the metabolomic profiling of embryo culture media and follicular fluid has been used to assess oocyte and embryo quality and viability. [234–242]

Recently, Heazell et al. [243] used gas-chromatography-mass spectroscopy to examine the metabolic profile of conditioned culture media and tissue lysates of placental villous explants from normal pregnant women cultured at different oxygen tensions. This study demonstrated that detection of the placental metabolic footprint is feasible, and that this metabolic footprint was different among placental samples as a function of the oxygen tension used for culture. Hexadecanoic acid, threitol or erythritol, and 2-deoxyribose were among the most differentially expressed metabolites. The same authors[244] conducted a similar study using Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) in serum-conditioned culture medium of villous trophoblast from placentas of normal pregnant women and patients with preeclampsia. The relative concentration of 154 metabolites was significantly different in culture medium from normal pregnancies between normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Interestingly, 47 metabolites in preeclampsia-derived conditioned media cultured under normoxic conditions had a comparable relative concentration to that of those from normal placentas cultured in hypoxic conditions, suggesting that hypoxia may have a role in preeclampsia. Three metabolic pathways (glutamate and glutamine, tryptophan metabolism and leukotriene or prostaglandin metabolism) were considered of interest for future studies to determine their role in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. [244]

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy has been used for more than 10 years to explore the metabolomic profile of the amniotic fluid to determine fetal lung[245,246] and kidney maturation, [247] as well as in other pathologic conditions such Down syndrome, [247] and open spina bifida. [247,248] Recently, 1H NMR coupled with LC-NMR/MS has been applied to further characterize the metabolic composition of the amniotic fluid[249,250] and to determine its possible role as a diagnostic method for fetal malformations. The advantage of NMR analysis is that it is non-destructive of the samples. On the other hand the metabolomics technique described in the present manuscript has a superior sensitivity. Graça et al. [251] studied amniotic fluid from midtrimester genetic amniocenteses of 51 normal pregnant women and 12 pregnancies with fetal anomalies. Maternal age, fetal gender, and maternal age at amniocentesis did not change the metabolic profile of amniotic fluid of normal pregnant women. Using Principal Component Analysis, no differences were observed between the amniotic fluid samples from normal pregnancies and those with fetal malformations. However, orthogonal variant Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis differentiated the two groups by identifying changes in glucose, succinate, and eight amino acids, as well as changes in the protein fraction and in the ratio of free to protein-interacting lactate. The authors suggest that these changes may represent a shift in energy production towards glycolysis due to hypoxia. [251]

In conclusion, this is the first draft of the human amniotic fluid metabolome in patients with spontaneous preterm labor with intact membranes. A stereotypic pattern of metabolites was identified in clinical groups with different outcomes, and global changes in the metabolic profile of the amniotic fluid allowed classification of patients at risk for preterm delivery (88% accuracy). Characterization of the human amniotic fluid metabolome can serve as the basis for the development of rapid tests to identify the patient at risk for impending preterm birth from the patient who will deliver at term, in the presence or absence of intra-amniotic infection/inflammation. Further studies with more sensitive tools could increase the number of metabolites identified in amniotic fluid and improve the draft of the amniotic fluid metabolome reported herein. In addition to the study of amniotic fluid, metabolomics characterization of maternal plasma, urine and cervico-vaginal fluid can be of great importance. Insights gained from these studies could help improve the understanding of metabolism of the fetus and fetal membranes in normal and pathologic conditions.

Supplementary Material

Reference List

- 1.Romero R. The child is the father of the man. Prenat Neonat Med. 1996:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Renzo GC. The great obstetrical syndromes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:633–635. doi: 10.1080/14767050902866804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romero R. Prenatal medicine: the child is the father of the man. 1996. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:636–639. doi: 10.1080/14767050902784171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romero R, Espinoza J, Kusanovic JP, Gotsch F, Hassan S, Erez O, Chaiworapongsa T, Mazor M. The preterm parturition syndrome. BJOG. 2006;113 (Suppl 3):17–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esplin MS, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Kim YM, Edwin S, Gomez R, Mazor M, Adashi EY. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 is increased in the amniotic fluid of women who deliver preterm in the presence or absence of intra-amniotic infection. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;17:365–373. doi: 10.1080/14767050500141329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soto E, Espinoza J, Nien JK, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Richani K, Santolaya-Forgas J, Romero R. Human beta-defensin-2: a natural antimicrobial peptide present in amniotic fluid participates in the host response to microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20:15–22. doi: 10.1080/14767050601036212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaiworapongsa T, Hong JS, Hull WM, Romero R, Whitsett JA. Amniotic fluid concentration of surfactant proteins in intra-amniotic infection. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:663–670. doi: 10.1080/14767050802215664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaiworapongsa T, Erez O, Kusanovic JP, Vaisbuch E, Mazaki-Tovi S, Gotsch F, Than NG, Mittal P, Kim YM, Camacho N, et al. Amniotic fluid heat shock protein 70 concentration in histologic chorioamnionitis, term and preterm parturition. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:449–461. doi: 10.1080/14767050802054550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gotsch F, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Erez O, Vaisbuch E, Espinoza J, Kusanovic JP, Mittal P, Mazaki-Tovi S, Kim CJ, et al. Evidence of the involvement of caspase-1 under physiologic and pathologic cellular stress during human pregnancy: a link between the inflammasome and parturition. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:605–616. doi: 10.1080/14767050802212109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gotsch F, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Espinoza J, Kim CJ, Vaisbuch E, Than NG, Mazaki-Tovi S, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. The anti-inflammatory limb of the immune response in preterm labor, intra-amniotic infection/inflammation, and spontaneous parturition at term: a role for interleukin-10. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:529–547. doi: 10.1080/14767050802127349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamill N, Romero R, Gotsch F, Kusanovic JP, Edwin S, Erez O, Than NG, Mittal P, Espinoza J, Friel LA, et al. Exodus-1 (CCL20): evidence for the participation of this chemokine in spontaneous labor at term, preterm labor, and intrauterine infection. J Perinat Med. 2008;36:217–227. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2008.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kusanovic JP, Romero R, Mazaki-Tovi S, Chaiworapongsa T, Mittal P, Gotsch F, Erez O, Vaisbuch E, Edwin SS, Than NG, et al. Resistin in amniotic fluid and its association with intra-amniotic infection and inflammation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:902–916. doi: 10.1080/14767050802320357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SE, Romero R, Park CW, Jun JK, Yoon BH. The frequency and significance of intraamniotic inflammation in patients with cervical insufficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:633–638. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SE, Romero R, Park IS, Seong HS, Park CW, Yoon BH. Amniotic fluid prostaglandin concentrations increase before the onset of spontaneous labor at term. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:89–94. doi: 10.1080/14767050701830514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Gotsch F, Mittal P, Than NG, Nhan-Chang CL, Hamill N, Vaisbuch E, et al. Visfatin/Pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor in amniotic fluid in normal pregnancy, spontaneous labor at term, preterm labor and prelabor rupture of membranes: an association with subclinical intrauterine infection in preterm parturition. J Perinat Med. 2008;36:485–496. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2008.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mittal P, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Edwin SS, Gotsch F, Mazaki-Tovi S, Espinoza J, Erez O, Nhan-Chang CL, Than NG, et al. CXCL6 (granulocyte chemotactic protein-2): a novel chemokine involved in the innate immune response of the amniotic cavity. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;60:246–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00620.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romero R, Espinoza J, Hassan S, Gotsch F, Kusanovic JP, Avila C, Erez O, Edwin S, Schmidt AM. Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) and endogenous secretory RAGE (esRAGE) in amniotic fluid: modulation by infection and inflammation. J Perinat Med. 2008;36:388–398. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2008.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaisbuch E, Romero R, Erez O, Kusanovic JP, Gotsch F, Than NG, Mazaki-Tovi S, Mittal P, Edwin S, Hassan SS. Total hemoglobin concentration in amniotic fluid is increased in intraamniotic infection/inflammation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:426–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cruciani L, Romero R, Vaisbuch E, Kusanovic JP, Chaiworapongsa T, Mazaki-Tovi S, Mittal P, Ogge G, Gotsch F, Erez O, et al. Pentraxin 3 in amniotic fluid: a novel association with intra-amniotic infection and inflammation. J Perinat Med. 2010;38:161–171. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2009.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erez O, Romero R, Vaisbuch E, Chaiworapongsa T, Kusanovic JP, Mazaki-Tovi S, Gotsch F, Gomez R, Maymon E, Pacora P, et al. Changes in amniotic fluid concentration of thrombin-antithrombin III complexes in patients with preterm labor: Evidence of an increased thrombin generation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009:1–12. doi: 10.3109/14767050902994762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kusanovic JP, Romero R, Jodicke C, Mazaki-Tovi S, Vaisbuch E, Erez O, Mittal P, Gotsch F, Chaiworapongsa T, Edwin SS, et al. Amniotic fluid soluble human leukocyte antigen-G in term and preterm parturition, and intra-amniotic infection/inflammation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:1–12. doi: 10.3109/14767050903019684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Vaisbuch E, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Mittal P, Gotsch F, Chaiworapongsa T, Than NG, Kim SK, et al. Adiponectin in amniotic fluid in normal pregnancy, spontaneous labor at term, and preterm labor: A novel association with intra-amniotic infection/inflammation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009:1–11. doi: 10.3109/14767050903026481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pacora P, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Vaisbuch E, Mazaki-Tovi S, Gotsch F, Jai KC, Than NG, et al. Amniotic fluid angiopoietin-2 in term and preterm parturition, and intra-amniotic infection/inflammation. J Perinat Med. 2009;37:503–511. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2009.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Romero R, Pedro KJ, Munoz H, Gomez R, Lamont RF, Yeo L. Allergy-induced preterm labor after the ingestion of shellfish. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:351–359. doi: 10.3109/14767050903177193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Gomez R, Lamont R, Bytautiene E, Garfield RE, Mittal P, Hassan SS, Yeo L. The clinical significance of eosinophils in the amniotic fluid in preterm labor. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:320–329. doi: 10.3109/14767050903168465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soto E, Romero R, Richani K, Yoon BH, Chaiworapongsa T, Vaisbuch E, Mittal P, Erez O, Gotsch F, Mazor M, et al. Evidence for complement activation in the amniotic fluid of women with spontaneous preterm labor and intra-amniotic infection. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:983–992. doi: 10.3109/14767050902994747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaisbuch E, Romero R, Erez O, Mazaki-Tovi S, Pedro KJ, Soto E, Gotsch F, Dong Z, Chaiworapongsa T, Kim SK, et al. Fragment Bb in amniotic fluid: evidence for complement activation by the alternative pathway in women with intra-amniotic infection/inflammation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:905–916. doi: 10.1080/14767050902994663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaisbuch E, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Mazaki-Tovi S, Gotsch F, Kim CJ, Kim JS, Chaiworapongsa T, Edwin S, Than NG, et al. Amniotic fluid fetal hemoglobin in normal pregnancies and pregnancies complicated with preterm labor or prelabor rupture of membranes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:388–397. doi: 10.1080/14767050802578285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kusanovic JP, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Mittal P, Mazaki-Tovi S, Vaisbuch E, Erez O, Gotsch F, Gabor TN, Edwin SS, et al. Amniotic fluid sTREM-1 in normal pregnancy, spontaneous parturition at term and preterm, and intra-amniotic infection/inflammation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:34–47. doi: 10.3109/14767050903009248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaisbuch E, Mazaki-Tovi S, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Nandor GT, Kim SK, Dong Z, Gotsch F, Mittal P, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Retinol binding protein 4: An adipokine associated with intra-amniotic infection/inflammation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:111–119. doi: 10.3109/14767050902994739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Tarca A, Pedro KJ, Mittal P, Kwon KS, Gotsch F, Erez O, Vaisbuch E, Mazaki-Tovi S, et al. A subset of patients destined to develop spontaneous preterm labor has an abnormal angiogenic/anti-angiogenic profile in maternal plasma: evidence in support of pathophysiologic heterogeneity of preterm labor derived from a longitudinal study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:1122–1139. doi: 10.3109/14767050902994838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Vaisbuch E, Erez O, Mittal P, Chaiworapongsa T, Kim SK, Pacora P, Yeo L, Gotsch F, et al. Dysregulation of maternal serum adiponectin in preterm labor. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:887–904. doi: 10.1080/14767050902994655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Vaisbuch E, Erez O, Chaiworapongsa T, Mittal P, Kim SK, Pacora P, Gotsch F, Dong Z, et al. Maternal plasma visfatin in preterm labor. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:693–704. doi: 10.1080/14767050902994788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Pineles BL, Gotsch F, Mittal P, Than NG, Espinoza J, Hassan SS. Recurrent preterm birth. Semin Perinatol. 2007;31:142–158. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim JS, Romero R, Cushenberry E, Kim YM, Erez O, Nien JK, Yoon BH, Espinoza J, Kim CJ. Distribution of CD14+ and CD68+ macrophages in the placental bed and basal plate of women with preeclampsia and preterm labor. Placenta. 2007;28:571–576. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Espinoza J, Kim YM, Edwin S, Bujold E, Gomez R, Kuivaniemi H. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in patients with preterm parturition and microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;18:405–416. doi: 10.1080/14767050500361703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nathanielsz PW. A time to be born: implications of animal studies in maternal-fetal medicine. Birth. 1994;21:163–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1994.tb00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lappas M, Permezel M, Georgiou HM, Rice GE. Type II phospholipase A2 in preterm human gestational tissues. Placenta. 2001;22:64–69. doi: 10.1053/plac.2000.0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bethin KE, Nagai Y, Sladek R, Asada M, Sadovsky Y, Hudson TJ, Muglia LJ. Microarray analysis of uterine gene expression in mouse and human pregnancy. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1454–1469. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meadows JW, Eis AL, Brockman DE, Myatt L. Expression and localization of prostaglandin E synthase isoforms in human fetal membranes in term and preterm labor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:433–439. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitchell MD, Simpson KL, Keelan JA. Paradoxical proinflammatory actions of interleukin-10 in human amnion: potential roles in term and preterm labour. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4149–4152. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maul H, Mackay L, Garfield RE. Cervical ripening: biochemical, molecular, and clinical considerations. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49:551–563. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200609000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bruni L, Luisi S, Ferretti C, Janneau JL, Quadrifoglio M, Richon S, Dangles-Marie V, Bellet D, Petraglia F. Changes in the maternal serum concentration of proearly placenta insulin-like growth factor peptides in normal vs abnormal pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:606–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maner WL, Garfield RE. Identification of human term and preterm labor using artificial neural networks on uterine electromyography data. Ann Biomed Eng. 2007;35:465–473. doi: 10.1007/s10439-006-9248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blank V, Hirsch E, Challis JR, Romero R, Lye SJ. Cytokine signaling, inflammation, innate immunity and preterm labour - a workshop report. Placenta. 2008;29 (Suppl A):S102–S104. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Casciani V, Premyslova M, Luo D, Marinoni E, Moscarini M, Di Iorio R, Challis JR. Effect of calcium ionophore A23187 on prostaglandin synthase type 2 and 15-hydroxy-prostaglandin dehydrogenase expression in human chorion trophoblast cells. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:554–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shynlova O, Tsui P, Dorogin A, Lye SJ. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (CCL-2) integrates mechanical and endocrine signals that mediate term and preterm labor. J Immunol. 2008;181:1470–1479. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Challis JR, Lockwood CJ, Myatt L, Norman JE, Strauss JF, III, Petraglia F. Inflammation and pregnancy. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:206–215. doi: 10.1177/1933719108329095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lappas M, Rice GE. Transcriptional regulation of the processes of human labour and delivery. Placenta. 2009;30 (Suppl A):S90–S95. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stella CL, Bennett MR, Devarajan P, Greis K, Wyder M, Macha S, Rao M, Jodicke C, Moussa H, How HY, et al. Preterm labor biomarker discovery in serum using 3 proteomic profiling methodologies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:387–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leguizamon G, Smith J, Younis H, Nelson DM, Sadovsky Y. Enhancement of amniotic cyclooxygenase type 2 activity in women with preterm delivery associated with twins or polyhydramnios. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:117–122. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.108076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hirsch E, Goldstein M, Filipovich Y, Wang H. Placental expression of enzymes regulating prostaglandin synthesis and degradation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1836–1842. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bastek JA, Sammel MD, Pare E, Srinivas SK, Posencheg MA, Elovitz MA. Adverse neonatal outcomes: examining the risks between preterm, late preterm, and term infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:367–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elovitz MA, Gonzalez J. Medroxyprogesterone acetate modulates the immune response in the uterus, cervix and placenta in a mouse model of preterm birth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:223–230. doi: 10.1080/14767050801923680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simhan HN, Krohn MA. Paternal race and preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:644–646. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Filipovich Y, Lu SJ, Akira S, Hirsch E. The adaptor protein MyD88 is essential for E coli-induced preterm delivery in mice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simhan HN, Krohn MA. First-trimester cervical inflammatory milieu and subsequent early preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:377–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elovitz MA, Baron J, Phillippe M. The role of thrombin in preterm parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1059–1063. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goldenberg RL, Iams JD, Mercer BM, Meis PJ, Moawad A, Das A, Miodovnik M, Vandorsten PJ, Caritis SN, Thurnau G, et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: toward a multiple-marker test for spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:643–651. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.116752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Mercer BM, Moawad AH, Meis PJ, Das AF, Caritis SN, Miodovnik M, Menard MK, Thurnau GR, et al. The preterm prediction study: can low-risk women destined for spontaneous preterm birth be identified? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:652–655. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.111248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goldenberg RL, Iams JD, Mercer BM, Meis P, Moawad A, Das A, Copper R, Johnson F. What we have learned about the predictors of preterm birth. Semin Perinatol. 2003;27:185–193. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(03)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalish RB, Vardhana S, Normand NJ, Gupta M, Witkin SS. Association of a maternal CD14 -159 gene polymorphism with preterm premature rupture of membranes and spontaneous preterm birth in multi-fetal pregnancies. J Reprod Immunol. 2006;70:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Diamond AK, Sweet LM, Oppenheimer KH, Bradley DF, Phillippe M. Modulation of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 expression during lipopolysaccharide-induced preterm delivery in the pregnant mouse. Reprod Sci. 2007;14:548–559. doi: 10.1177/1933719107307792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chaves JH, Babayan A, Bezerra CM, Linhares IM, Witkin SS. Maternal and neonatal interleukin-1 receptor antagonist genotype and pregnancy outcome in a population with a high rate of pre-term birth. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;60:312–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Iams JD, Romero R, Culhane JF, Goldenberg RL. Primary, secondary, and tertiary interventions to reduce the morbidity and mortality of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:164–175. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ratajczak CK, Muglia LJ. Insights into parturition biology from genetically altered mice. Pediatr Res. 2008;64:581–589. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31818718d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berghella V, Baxter JK, Hendrix NW. Cervical assessment by ultrasound for preventing preterm delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD007235. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007235.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carlin A, Norman J, Cole S, Smith R. Tocolytics and preterm labour. BMJ. 2009;338:b195. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Defranco EA, Chang JJ, Macones GA, Muglia LJ. The correlation in birth timing between singleton and twin gestations in the same mother. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:106–110. doi: 10.1080/14767050802488204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scheib S, Visintine JF, Miroshnichenko G, Harvey C, Rychlak K, Berghella V. Is cerclage height associated with the incidence of preterm birth in women with an ultrasound-indicated cerclage? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:e12–e15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith R, Smith JI, Shen X, Engel PJ, Bowman ME, McGrath SA, Bisits AM, McElduff P, Giles WB, Smith DW. Patterns of plasma corticotropin-releasing hormone, progesterone, estradiol, and estriol change and the onset of human labor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2066–2074. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nien JK, Yoon BH, Espinoza J, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Soto E, Richani K, Gomez R, Hassan S, Mazor M, et al. A rapid MMP-8 bedside test for the detection of intra-amniotic inflammation identifies patients at risk for imminent preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1025–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Romero R, Espinoza J, Gotsch F, Kusanovic JP, Friel LA, Erez O, Mazaki-Tovi S, Than NG, Hassan S, Tromp G. The use of high-dimensional biology (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) to understand the preterm parturition syndrome. BJOG. 2006;113 (Suppl 3):118–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Romero R, Tromp G. High-dimensional biology in obstetrics and gynecology: functional genomics in microarray studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:360–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Evans GA. Designer science and the “omic” revolution. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:127. doi: 10.1038/72480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gracey AY, Cossins AR. Application of microarray technology in environmental and comparative physiology. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:231–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mehta T, Tanik M, Allison DB. Towards sound epistemological foundations of statistical methods for high-dimensional biology. Nat Genet. 2004;36:943–947. doi: 10.1038/ng1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Weinstein JN. Fishing expeditions. Science. 1998;282:628–629. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.627g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Weinstein JN. ‘Omic’ and hypothesis-driven research in the molecular pharmacology of cancer. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2:361–365. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(02)00185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Collins FS, Guttmacher AE. Genetics moves into the medical mainstream. JAMA. 2001;286:2322–2324. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.18.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Collins FS, Mansoura MK. The Human Genome Project. Revealing the shared inheritance of all humankind. Cancer. 2001;91:221–225. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1+<221::aid-cncr8>3.3.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ginsburg GS, McCarthy JJ. Personalized medicine: revolutionizing drug discovery and patient care. Trends Biotechnol. 2001;19:491–496. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(01)01814-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McKusick VA. The anatomy of the human genome: a neo-Vesalian basis for medicine in the 21st century. JAMA. 2001;286:2289–2295. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.18.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Subramanian G, Adams MD, Venter JC, Broder S. Implications of the human genome for understanding human biology and medicine. JAMA. 2001;286:2296–2307. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.18.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hegde PS, White IR, Debouck C. Interplay of transcriptomics and proteomics. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2003;14:647–651. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schena M, Shalon D, Davis RW, Brown PO. Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. Science. 1995;270:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lipshutz RJ, Morris D, Chee M, Hubbell E, Kozal MJ, Shah N, Shen N, Yang R, Fodor SP. Using oligonucleotide probe arrays to access genetic diversity. Biotechniques. 1995;19:442–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Petricoin EF, Ardekani AM, Hitt BA, Levine PJ, Fusaro VA, Steinberg SM, Mills GB, Simone C, Fishman DA, Kohn EC, et al. Use of proteomic patterns in serum to identify ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2002;359:572–577. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07746-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Phizicky E, Bastiaens PI, Zhu H, Snyder M, Fields S. Protein analysis on a proteomic scale. Nature. 2003;422:208–215. doi: 10.1038/nature01512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Han X, Gross RW. Global analyses of cellular lipidomes directly from crude extracts of biological samples by ESI mass spectrometry: a bridge to lipidomics. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:1071–1079. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R300004-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lagarde M, Geloen A, Record M, Vance D, Spener F. Lipidomics is emerging. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1634:61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wenk MR. The emerging field of lipidomics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:594–610. doi: 10.1038/nrd1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Goodacre R, Vaidyanathan S, Dunn WB, Harrigan GG, Kell DB. Metabolomics by numbers: acquiring and understanding global metabolite data. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jain S, Jayasimhulu K, Clark JF. Metabolomic analysis of molecular species of phospholipids from normotensive and preeclamptic human placenta electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Front Biosci. 2004;9:3167–3175. doi: 10.2741/1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nobeli I, Thornton JM. A bioinformatician’s view of the metabolome. Bioessays. 2006;28:534–545. doi: 10.1002/bies.20414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wishart DS, Tzur D, Knox C, Eisner R, Guo AC, Young N, Cheng D, Jewell K, Arndt D, Sawhney S, et al. HMDB: the Human Metabolome Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D521–D526. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rochfort S. Metabolomics reviewed: a new “omics” platform technology for systems biology and implications for natural products research. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:1813–1820. doi: 10.1021/np050255w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vuadens F, Benay C, Crettaz D, Gallot D, Sapin V, Schneider P, Bienvenut WV, Lemery D, Quadroni M, Dastugue B, et al. Identification of biologic markers of the premature rupture of fetal membranes: proteomic approach. Proteomics. 2003;3:1521–1525. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gravett MG, Novy MJ, Rosenfeld RG, Reddy AP, Jacob T, Turner M, McCormack A, Lapidus JA, Hitti J, Eschenbach DA, et al. Diagnosis of intra-amniotic infection by proteomic profiling and identification of novel biomarkers. JAMA. 2004;292:462–469. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ruetschi U, Rosen A, Karlsson G, Zetterberg H, Rymo L, Hagberg H, Jacobsson B. Proteomic analysis using protein chips to detect biomarkers in cervical and amniotic fluid in women with intra-amniotic inflammation. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:2236–2242. doi: 10.1021/pr050139e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cobo T, Palacio M, Navarro-Sastre A, Ribes A, Bosch J, Filella X, Gratacos E. Predictive value of combined amniotic fluid proteomic biomarkers and interleukin-6 in preterm labor with intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:499–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shah SJ, Yu KH, Sangar V, Parry SI, Blair IA. Identification and quantification of preterm birth biomarkers in human cervicovaginal fluid by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:2407–2417. doi: 10.1021/pr8010342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Horgan RP, Clancy OH, Myers JE, Baker PN. An overview of proteomic and metabolomic technologies and their application to pregnancy research. BJOG. 2009;116:173–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bujold E, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Gotsch F, Chaiworapongsa T, Gomez R, Espinoza J, Vaisbuch E, Mee KY, et al. Proteomic profiling of amniotic fluid in preterm labor using two-dimensional liquid separation and mass spectrometry. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:697–713. doi: 10.1080/14767050802053289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Klein LL, Jonscher KR, Heerwagen MJ, Gibbs RS, McManaman JL. Shotgun proteomic analysis of vaginal fluid from women in late pregnancy. Reprod Sci. 2008;15:263–273. doi: 10.1177/1933719107311189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cho CK, Shan SJ, Winsor EJ, Diamandis EP. Proteomics analysis of human amniotic fluid. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1406–1415. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700090-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dasari S, Pereira L, Reddy AP, Michaels JE, Lu X, Jacob T, Thomas A, Rodland M, Roberts CT, Jr, Gravett MG, et al. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of human cervical-vaginal fluid. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:1258–1268. doi: 10.1021/pr0605419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pereira L, Reddy AP, Jacob T, Thomas A, Schneider KA, Dasari S, Lapidus JA, Lu X, Rodland M, Roberts CT, Jr, et al. Identification of novel protein biomarkers of preterm birth in human cervical-vaginal fluid. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:1269–1276. doi: 10.1021/pr0605421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Di Quinzio MK, Oliva K, Holdsworth SJ, Ayhan M, Walker SP, Rice GE, Georgiou HM, Permezel M. Proteomic analysis and characterisation of human cervico-vaginal fluid proteins. Aust NZJ Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47:9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gomez R, Romero R, Nien JK, Medina L, Carstens M, Kim YM, Espinoza J, Chaiworapongsa T, Gonzalez R, Iams JD, et al. Antibiotic administration to patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes does not eradicate intra-amniotic infection. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20:167–173. doi: 10.1080/14767050601135485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Romero R, Quintero R, Nores J, Avila C, Mazor M, Hanaoka S, Hagay Z, Merchant L, Hobbins JC. Amniotic fluid white blood cell count: a rapid and simple test to diagnose microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity and predict preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:821–830. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90423-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yoon BH, Romero R, Moon JB, Shim SS, Kim M, Kim G, Jun JK. Clinical significance of intra-amniotic inflammation in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1130–1136. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Romero R, Emamian M, Quintero R, Wan M, Hobbins JC, Mazor M, Edberg S. The value and limitations of the Gram stain examination in the diagnosis of intraamniotic infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:114–119. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Romero R, Jimenez C, Lohda AK, Nores J, Hanaoka S, Avila C, Callahan R, Mazor M, Hobbins JC, Diamond MP. Amniotic fluid glucose concentration: a rapid and simple method for the detection of intraamniotic infection in preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:968–974. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91106-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Andreoli R, Manini P, Poli D, Bergamaschi E, Mutti A, Niessen WM. Development of a simplified method for the simultaneous determination of retinol, alpha-tocopherol, and beta-carotene in serum by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry with atmospheric pressure chemical ionization. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2004;378:987–994. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gehrke CW, Leimer K. Trimethylsilylation of amino acids derivatization and chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1971;57:219–238. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(71)80035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Evans AM, Dehaven CD, Barrett T, Mitchell M, Milgram E. Integrated, Nontargeted Ultrahigh Performance Liquid Chromatography/Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry Platform for the Identification and Relative Quantification of the Small-Molecule Complement of Biological Systems. Anal Chem. 2009;81:6656–6667. doi: 10.1021/ac901536h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Liaw A, Wiener M. Classication and Regression by random Forest. R news. 2002;2:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Breiman L. Technical Note: Some Properties of Splitting Criteria. Machine Learning. 1966;24:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gomez R, Romero R, Ghezzi F, Yoon BH, Mazor M, Berry SM. The fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:194–202. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Romero R, Gomez R, Ghezzi F, Yoon BH, Mazor M, Edwin SS, Berry SM. A fetal systemic inflammatory response is followed by the spontaneous onset of preterm parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:186–193. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Gotsch F, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Mazaki-Tovi S, Pineles BL, Erez O, Espinoza J, Hassan SS. The fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50:652–683. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31811ebef6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Madsen-Bouterse SA, Romero R, Tarca AL, Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, Kim CJ, Kim JS, Edwin SS, Gomez R, Draghici S. The transcriptome of the fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63:73–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yoon BH, Romero R, Jun JK, Maymon E, Gomez R, Mazor M, Park JS. An increase in fetal plasma cortisol but not dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate is followed by the onset of preterm labor in patients with preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1107–1114. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70114-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]