Abstract

Background

A distinction between symptomatic non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) and erosive esophagitis (EE) patientsis supported by the presence of inflammatory response in the mucosa of EE patients, leading to a damage of mucosal integrity. To explore the underlying mechanism of this difference we assessed inflammatory mediators in mucosal biopsies from EE and NERD patients and compared them to controls.

Methods

Nineteen NERD patients, fifteen EE patients and sixteen healthy subjects underwent endoscopy after a 3-week washout from PPI or H2 antagonists. Biopsies obtained from the distal esophagus, were examined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and multiplex ELISA for selected chemokines and lyso-PAF acetyltransferase (LysoPAF-AT), the enzyme responsible for production of platelet activating factor (PAF).

Results

Expression of LysoPAF-AT and multiple chemokines was significantly increased in mucosal biopsies derived from EE patients, when compared to NERD patients and healthy controls. Upregulated chemokines included interleukin 8, eotaxin-1, -2 and -3, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1). LysoPAF-AT and the chemokine profile in NERD patients were comparable to healthy controls.

Conclusions

Levels of selected cytokines and Lyso-PAF AT were significantly higher in the esophageal mucosa of EE patients compared to NERD and control patients. This difference may explain the distinct inflammatory response occurring in EE patients’ mucosa. In contrast, since no significant differences existed between the levels of all mediators in NERD and control subjects, an inflammatory response does not appear to play a major role in the pathogenesis of the abnormalities found in NERD patients.

Keywords: Gastroesophageal reflux disease, chemokines, PAF, esophageal inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a multifactorial disease that affects more than 20% of the adult population of Western countries, with a significant impact on quality of life and the potential for developing esophagitis, esophageal strictures and Barrett’s esophagus. (1–3) However, 50–70% of GERD patients do not develop esophageal erosions, and are classified as non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) patients (4, 5). Although several reports suggest a possible progression of NERD to erosive esophagitis (EE), clinical, endoscopic and molecular characteristics differentiate these two GERD groups and the response of NERD patients to acid suppressive therapy is less effective than in patients with EE (6). In patients with NERD, esophageal visceral hypersensitivity, impaired mucosal integrity and sustained esophageal contractions have been proposed as possible mechanisms underlying reflux symptoms (6).

Both GERD groups present a similar increase in esophageal mucosa expression of transient receptor potential channel vanilloid subfamily member-1 (TRPV1) mRNA and protein when compared to asymptomatic healthy controls (7). Acid-induced inflammation of the esophagus is triggered by activation of acid sensitive TRPV1 receptors in the mucosa that, in turn, causes release of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (8), platelet activating factor (PAF) (9) and several chemokines including interleukin-8 (IL-8) (10) from epithelial cells. ATP released from epithelial cells is thought to affect sensory pathways beyond the submucosal plexus (11), possibly mediating pain by acting on the sensory nerve terminals extending to the mucosa (12).

PAF is a phospholipid mediator that activates a G protein-coupled receptor and results in several biological effects, including platelet activation, airway constriction, and hypotension (13, 14). In an animal model of acute esophagitis, Paterson et al. showed that acid perfusion induced release of PAF from the esophageal mucosa into the lumen and significant epithelial injury, which could be prevented by a PAF-antagonist (15).

We recently demonstrated that acid-induced production of IL-8, PAF and SP by the esophageal mucosa promotes migration of peripheral blood leucocytes. In addition, PAF and SP induce production of H2O2 by peripheral blood leucocytes (10).

Microscopic inflammation, characterized by neutrophilic and eosinophilic infiltration of the esophageal mucosa and submucosa, is more commonly observed in EE than NERD patients (7, 16, 17). A possible explanation for the diverse esophageal phenotypes of GERD may be the presence of different soluble mediators responsible for mucosal immune and inflammatory responses in these groups of patients (18, 19–22).

PAF is known to induce aggregation and stimulation of immune cells and is one of the most potent chemoattractants for eosinophils (23, 24). Other factors are chemotactic for neutrophils, eosinophils and monocytic cells, such as IL-8, eotaxin-1, eotaxin-2, eotaxin-3, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) (25, 26). To explore the mechanism underlying inflammation in EE patients, we examined mucosal biopsies from NERD and EE patients as well as in controls, focusing on the expression of LysoPAF-AT and several chemokines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

A total of 38 consecutive patients (16 female, 22 male, mean age 56 years, range 26–76) attending the out-patient units of Campus Bio Medico University of Rome between September 2009 and May 2010 participated in this study. Inclusion criteria were: recurrent typical GERD symptoms, such as heartburn and/or acid regurgitation and a duration of symptoms>6 months. Exclusion criteria were: presence of Barrett’s esophagus, peptic ulcer disease, history of gastrointestinal (GI) cancer and GI tract surgery (with the exception of appendectomy). Patients on proton pump inhibitors (PPI), H2-antagonists or prokinetic drugs underwent a 3-week pharmacological wash-out before upper endoscopy. The control group consisted of sixteen asymptomatic subjects, (9 female, 7 male, mean age 46 years, range 22–71), with no history of GERD. Clinical data were obtained using a standardized questionnaire for Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia (QOLRAD) (27) which was completed by all patients before endoscopy and following 2 week-treatment with PPIs.

The NERD patients, all symptomatic as defined by the questionnaire, had negative findings at endoscopy, and a satisfactory response to PPIs (>50% improvement in symptoms following 2-week treatment, according to the symptom score). Symptomatic patients with no esophageal mucosal injury, who had demonstrated evidence of esophageal erosive disease at previous endoscopic investigations, were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Campus Bio Medico University of Rome.

After overnight fasting, patients and controls underwent upper endoscopy, performed by the same operator (MPLG). A combination of midazolam and propofol was used for sedation. The distal portion of the esophagus was carefully evaluated in order to determine the presence of mucosal injury. A total of four biopsies from each individual, 2 for routine histological evaluation and 2 for analysis of LysoPAF-AT, IL-8, Eotaxin-1, Eotaxin-2, Eotaxin-3, MCP-1, MIP-1α gene expression, were taken at 5 cm above the squamo-columnar junction in NERD patients and in controls, and from normal appearing mucosa in EE patients. When sufficient material was available, the protein expression was measured by multiplex Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA).

Routine histological analysis

Two biopsies were collected for the routine histological evaluation; tissue fragment were fixed in buffered formalin for 12 h and embedded in paraffin with melting point 55–57 °C. Three to four micrometers sections were cut and stained with haematoxylin-eosin stain for morphological analysis.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA from human biopsies was isolated by RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). To eliminate DNA contamination one μg of total RNA was treated by DNAase I according to the product manual. RNA was reversely transcribed and subjected to real time PCR by using GeneAmp Gold RNA PCR Reagent Kit and Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) respectively. StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with StepOne Software (Version 2.1) was used for the real time PCR assay. Melting curve (dissociation curve) was run after the real time PCR to ensure that the desired amplicon was detected. 28S rRNA was used as the reference or housekeeper and comparative CT method was used to analyze the real time PCR data. Primers used are shown in table II.

Table II.

Primers used for RT-PCR analysis.

| Primers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lyso-PAF AT | Sense | 5′-ATTGACTTCCGAGAGTATGTGA-3′ | 85bp |

| Antisense | 5′-GCTTAAATGCCACCTGGATGA-3′ | ||

| IL-8 | Sense | 5′-ACTGAGAGTGATTGAGAGTGGAC-3′ | 112bp |

| Antisense | 5′-AACCCTCTGCACCCAGTTTTC-3′ | ||

| hMCP-1 | Sense | 5′-GATCTCAGTGCAGAGGCTCG-3′ | 153bp |

| Antisense | 5′-TGCTTGTCCAGGTGGTCCAT-3′ | ||

| hMIP-1α | Sense | 5′-TGCTTGTCCAGGTGGTCCAT-3′ | 212bp |

| Antisense | 5′-CACTCAGCTCCAGGTCGCTGAC-3′ | ||

| hEotaxin-1 | Sense | 5′-GAAACCACCACCTCTCACG-3′ | 190bp |

| Antisense | 5′-GCTCTCTAGTCGCTGAAGGG-3′ | ||

| hEotaxin-2 | Sense | 5′-GCAGGAGCACATGCCTCAA-3′ | 113bp |

| Antisense | 5′-GGCGTCCAGGTTCTTCATGTA-3′ | ||

| hEotaxin-3 | Sense | 5′-ATATCCAAGACCTGCTGCTTC-3′ | 152bp |

| Antisense | 5′-TTTTTCCTTGGATGGGTACAG-3′ |

IL-8, interleukin-8,; hEotaxin-1, human eotaxin-1; hEotaxin-2, human eotaxin-2; hEotaxin-3, human eotaxin-3; LysoPAF-AT, Lyso-PAF acetyl transferase; hMCP-1, human monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; hMIP-1α, human macrophage inflammatory protein-1α.

Multiplex ELISA Assay

When available, one biopsy (from EE, NERD and control patients) was homogenated in PBS with 1% Triton X-100, 5mM EDTA and proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich,St. Louis, MO,USA ), the protein was quantified and then adjusted to a concentration of 700ug/ml using PBS containing 0.5% BSA. The protein was then used for multiplex ELISA cytokine assay that included Eotaxin-1, IL-8, and MCP-1 according to the manufacturer’s manual (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistics

Data are expressed as means, and standard errors (SE). To assess inter-group variability the ANOVA test was performed and the Fisher Exact test was used to check for significance. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 54 subjects were examined, including 16 controls. No statistically significant differences, in age and sex, between healthy controls and patients were observed. Four patients in whom Barrett’s esophagus was revealed at endoscopy, were excluded from the study, thus the population comprised 34 patients and 16 controls.

Of the 34 patients studied, 19 (mean age 52 years, range 28–72) presented with NERD, and 15 (mean age 63 years, range 47–76) presented evidence of EE (Grade A in 10, Grade B in 4, Grade C in 1, according to the Los Angeles classification). Neutrophilic and eosinophilic infiltration, in the distal esophageal mucosa, was detected in all EE patients and in none of the NERD patients and of the controls.

Individual data of patients and tests used in this study are shown in Table I.

Table I.

PAF and selected chemokines mRNA and protein expression: individual data.

| Patient Name | Patient Type | IL-8 | EOT-1 | MCP-1 | EOT-2 | EOT-3 | LysoPAF-AT | MIP-1α | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Real-time PCR | Multiplex ELISA | Real-time PCR | Multiplex ELISA | Real-time PCR | Multiplex ELISA | ||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| mRNA relative expression | (pg/mg protein) | mRNA relative expression | (pg/mg protein) | mRNA relative expression | (pg/mg protein) | mRNA relative expression | mRNA relative expression | mRNA relative expression | mRNA relative expression | ||

|

|

|||||||||||

| CS | Control | 0,34 | -- | 1,71 | -- | 0,67 | -- | 1,49 | 0,78 | 1,17 | 1,08 |

| OM | Control | 1,66 | -- | 0,29 | -- | 1,33 | -- | 0,51 | 1,22 | 0,83 | 0,92 |

| BR | Control | 0,81 | -- | 1,33 | -- | 0,38 | -- | 0,68 | 0,84 | 1,02 | 1,23 |

| BG | Control | 1,19 | -- | 0,81 | -- | 1,39 | -- | 1,64 | 1,73 | 0,88 | -- |

| AR | Control | -- | -- | 0,86 | -- | 1,23 | -- | 0,69 | 0,43 | 1,10 | 0,77 |

| SK | Control | 1,43 | -- | 1,21 | -- | 0,41 | -- | 1,21 | 0,07 | 0,48 | 1,00 |

| SF | Control | 0,57 | -- | 0,79 | -- | 1,59 | -- | 0,79 | 1,93 | 1,52 | -- |

| PR | Control | 0,88 | -- | 0,55 | -- | 0,31 | -- | 1,63 | 1,96 | 0,63 | 0,57 |

| PS | Control | 0,85 | -- | 1,45 | -- | 1,69 | -- | 0,37 | 0,04 | 1,37 | 1,43 |

| PR2 | Control | 0,64 | 2,51 | 0,61 | 1,37 | 0,60 | 0,74 | 1,31 | 0,33 | 0,68 | 1,16 |

| CR | Control | 3,03 | 13,66 | 2,47 | 4,60 | 3,08 | 4,99 | 1,35 | 2,67 | 1,77 | 2,18 |

| CG | Control | 0,67 | 1,63 | 0,62 | 0,83 | 0,74 | 2,06 | 0,76 | 0,19 | 0,78 | 0,74 |

| VA | Control | 0,44 | 0,49 | 0,53 | 1,69 | 0,29 | 3,21 | 0,37 | 0,08 | 1,16 | 0,49 |

| VC | Control | 0,41 | 1,76 | 0,84 | 1,97 | 1,18 | 5,87 | 1,27 | 0,48 | 1,21 | -- |

| BC | Control | 0,62 | 1,20 | 0,32 | 1,63 | 0,50 | 2,94 | 0,54 | 0,56 | 1,05 | 0,74 |

| CS | Control | 1,96 | -- | 1,84 | -- | 1,32 | -- | 1,19 | 1,96 | 0,74 | 1,26 |

| TR | NERD | 0,73 | 7,43 | 10,15 | 3,01 | 5,14 | 4,51 | 1,39 | 3,38 | 7,90 | 1,30 |

| RP | NERD | 0,31 | 9,51 | 6,29 | 3,19 | 3,71 | 4,86 | 2,23 | 6,76 | 4,61 | -- |

| MA | NERD | 0,34 | -- | 7,42 | -- | 1,66 | -- | 0,68 | -- | 0,18 | -- |

| SO | NERD | 1,49 | 9,76 | 2,07 | 1,93 | 2,61 | 5,21 | 3,26 | 1,51 | 1,41 | 1,76 |

| OD | NERD | 3,45 | 2,03 | 3,43 | 3,20 | 2,36 | 5,61 | 15,66 | 8,94 | 3,21 | 3,60 |

| CE | NERD | 3,76 | 3,19 | 4,39 | 2,84 | 1,18 | 4,66 | 4,26 | 1,81 | 1,08 | 1,12 |

| GN | NERD | 1,12 | -- | 0,95 | -- | 0,94 | -- | 0,63 | 1,31 | 1,42 | 2,84 |

| MA | NERD | 1,68 | -- | 2,35 | -- | 1,18 | -- | 0,34 | 0,96 | 1,26 | 1,01 |

| HD | NERD | 1,02 | -- | 0,58 | -- | 0,11 | -- | 1,39 | 29,28 | 0,26 | 0,14 |

| VA | NERD | 0,09 | -- | 1,53 | -- | 0,60 | -- | 1,53 | 1,15 | 1,59 | 0,21 |

| LA | NERD | 0,05 | -- | 1,16 | -- | 1,76 | -- | 1,16 | 1,04 | 1,29 | 0,09 |

| GJ | NERD | 0,51 | -- | 1,12 | -- | 0,76 | -- | 0,41 | 0,44 | 0,37 | 2,08 |

| GA | NERD | 0,95 | -- | 0,49 | -- | 0,62 | -- | 0,33 | 0,21 | 0,64 | 2,11 |

| AD | NERD | 1,01 | -- | 0,32 | -- | 0,35 | -- | 0,48 | 0,08 | 0,60 | 0,83 |

| MI | NERD | 0,12 | -- | 0,67 | -- | 0,36 | -- | 0,34 | 0,55 | 0,86 | 0,34 |

| FL | NERD | 2,67 | -- | 0,10 | -- | 1,07 | -- | 0,27 | 2,87 | 0,35 | 2,27 |

| BM | NERD | 4,00 | -- | 0,61 | -- | 0,41 | -- | 0,07 | 4,21 | 0,31 | 0,30 |

| DM | NERD | 2,84 | -- | 0,48 | -- | 0,86 | -- | 0,78 | 0,43 | 0,60 | 0,63 |

| BR | NERD | 1,94 | -- | 0,25 | -- | 0,36 | -- | 0,70 | 0,83 | 0,39 | 0,38 |

| BA | EE | 8,32 | 11,94 | 4,28 | 6,23 | 1,25 | 8,39 | 0,51 | 11,97 | 0,56 | 0,95 |

| BG2 | EE | 2,98 | 27,03 | 0,20 | 4,44 | 0,74 | 11,37 | 1,15 | 26,39 | 1,30 | 1,50 |

| CL | EE | 2,94 | -- | 0,85 | -- | 1,44 | -- | 0,36 | 0,11 | 0,98 | 11,54 |

| BA2 | EE | 0,42 | -- | 1,73 | -- | 4,01 | -- | 1,73 | 5,76 | 1,22 | 14,43 |

| ZM | EE | 0,07 | -- | 2,07 | -- | 1,51 | -- | 2,07 | 0,52 | 1,25 | 1,85 |

| TO | EE | 2,98 | 27,03 | 0,20 | 4,44 | 0,74 | 11,37 | 1,15 | 26,39 | 1,30 | 1,50 |

| AS | EE | 17,67 | 110,56 | 1,74 | 15,67 | 1,27 | 7,29 | 4,06 | 2,92 | 5,78 | 3,22 |

| CF | EE | 44,00 | 21,10 | 16,44 | 28,20 | 3,45 | 19,59 | 7,32 | 2,94 | 7,95 | 8,12 |

| ZR | EE | 13,93 | 26,69 | 18,46 | 72,26 | 3,97 | 4,79 | 9,92 | 2,24 | 8,09 | 11,86 |

| BGA | EE | 3,81 | -- | 1,33 | -- | 0,99 | -- | 3,66 | 1,97 | 5,41 | 14,11 |

| CR | EE | 1,62 | -- | 6,62 | -- | 3,17 | -- | 12,67 | 5,57 | 4,59 | -- |

| AA | EE | 22,01 | -- | 3,95 | -- | 7,44 | -- | 15,70 | 13,04 | 7,93 | 9,65 |

| GD | EE | 19,85 | 18,50 | 1,72 | 4,43 | 1,57 | 7,13 | 17,71 | 12,49 | 1,26 | 1,28 |

| BS | EE | 28,70 | 163,16 | 2,37 | 8,20 | 8,80 | 43,07 | 1,95 | 1,38 | 8,17 | 2,03 |

| PR | EE | 15,38 | 40,84 | 5,99 | 5,54 | 1,29 | 14,16 | 31,98 | 3,99 | 11,15 | 4,08 |

| PT | EE | 4,79 | 15,14 | 12,85 | 37,31 | 8,43 | 46,06 | 3,24 | 5,69 | 2,37 | -- |

NERD, non-erosive reflux disease; EE, erosive esophagitis; IL-8, interleukin-8,;EOT-1, eotaxin-1; EOT-2, eotaxin 2; EOT-3, eotaxin 3; LysoPAF-AT, Lyso-PAF acetyl transferase; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MIP-1α, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α.

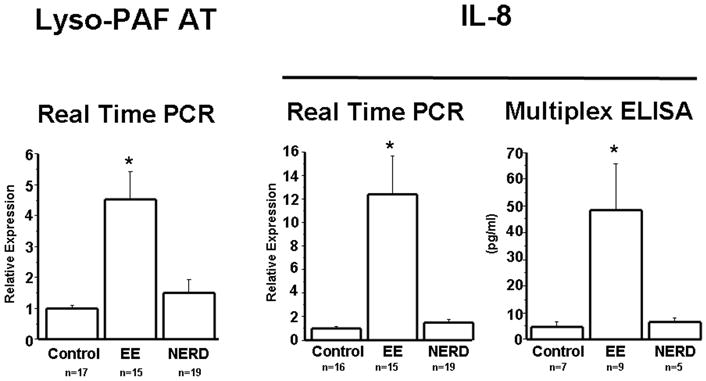

When biopsies from EE patients were examined, they contained significantly elevated levels of LysoPAF-AT mRNA when compared to biopsies of control and NERD subjects. Levels of LysoPAF-AT mRNA in biopsies from NERD patients were not significantly different from those of controls (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

LysoPAF-AT mRNA was measured by real time PCR in biopsies from controls as well as NERD and EE patients. The level of LysoPAF-AT mRNA expression was significantly increased in EE patients (p<0.001) when compared to NERD patients and controls. Differences in mRNA levels between NERD and controls were not statistically significant.

IL-8 mRNA was measured by real time PCR in biopsies from controls, NERD and EE patients. IL-8 protein was measured by multiplex ELISA. IL-8 mRNA (p<0.001) and protein (p<0.05) were significantly increased in EE patients when compared to NERD patients and controls. Differences in mRNA and protein levels between NERD and controls were not statistically significant.

The same biopsies examined for LysoPAF-AT content were used to measure IL-8 mRNA levels. Mimicking the results seen with LysoPAF-AT, IL-8 mRNA expression was significantly increased in biopsies from EE patients compared to NERD and control patients (Fig. 1). Protein levels of IL-8 were also measured in a subset of patients, and they confirmed the findings with IL-8 mRNA. IL-8 mRNA and protein expression in NERD patients were comparable to those of controls (Fig. 1).

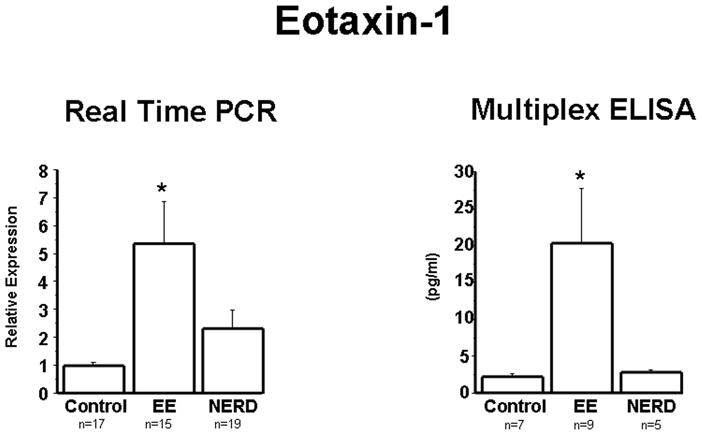

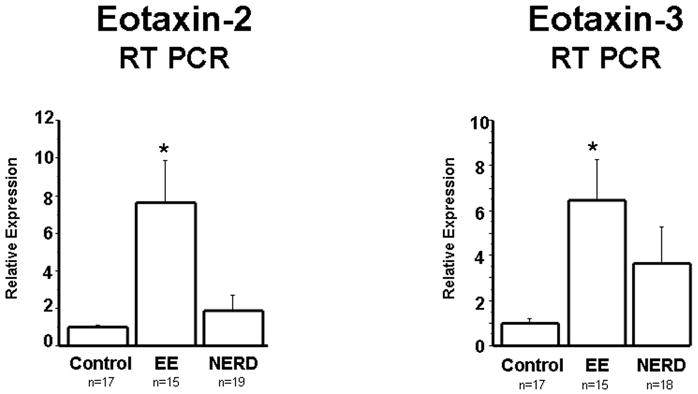

Next, the eosinophil chemoattractant eotaxin-1 was measured at the mRNA and protein levels, and the results obtained essentially reproduced the findings observed with IL-8 (Fig. 2). mRNA levels of eotaxin-2 and -3, chemokines with biological activity similar to that of eotaxin-1, were also measured (Fig. 3). Again, similar differences were observed, with EE patients exhibiting significantly higher levels of both eotaxin-1 and -2 in comparison to control and NERD patients, the latter two groups showing no significant differences between them.

Figure 2.

Eotaxin-1 mRNA was measured by real time PCR in biopsies from controls, NERD and EE patients. Eotaxin-1 protein was measured by multiplex ELISA. Eotaxin-1 mRNA (p<0.001) and protein (p<0.05) were significantly increased in EE patients when compared to NERD patients and controls. Differences in mRNA and protein levels between NERD and controls were not statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Eotaxin-2 and Eotaxin-3 mRNA was measured by real time PCR in biopsies from controls, NERD and EE patients. Eotaxin-2 (p<0.001) and Eotaxin-3 (p<0.05) mRNA were significantly increased in EE patients when compared to NERD patients and controls. Differences in mRNA between NERD and controls were not statistically significant.

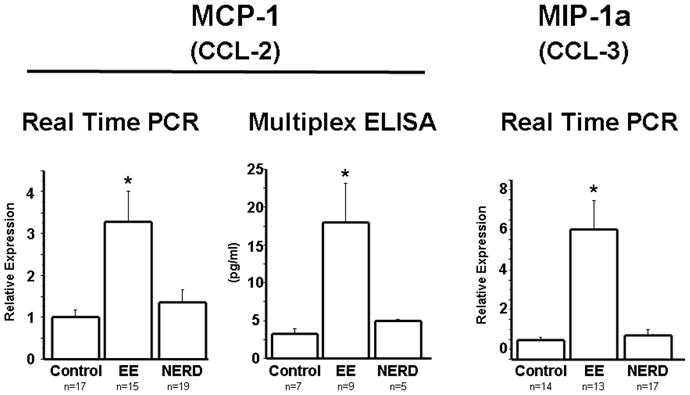

The differences detected for IL-8 and all three eotaxins were extended also to the monocytic cell chemokines MCP-1 and MIP-1α, and were confirmed at the protein level for MCP-1 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

MCP-1 and MIP-1α mRNA were measured by real time PCR in biopsies from controls, NERD and EE patients. MCP-1 protein was measured by multiplex ELISA. MCP-1 mRNA (p<0.001) and protein (p<0.05) were significantly increased in EE patients when compared to NERD patients and controls. Similarly MIP-1α mRNA was significantly increased in EE patients (p<0.001) when compared to NERD patients and controls. Differences in mRNA and protein levels between NERD and controls were not statistically significant.

Due the limited size of esophageal biopsies enough material was not obtained to perform ELISA or Western blotting for all mediators.

Discussion

The pathophysiology of GERD is still not well understood, but growing evidence indicates that NERD and EE patients represent two distinct categories of the GERD population. NERD patients are characterized by the same reflux-related symptoms as EE patients, but do not exhibit evidence of esophageal mucosal injury at conventional endoscopy (4, 5, 28).

A clear distinction between these two groups is provided by the number of neutrophils and eosinophils in the esophageal mucosa of EE patients, but not in the mucosa of NERD patients (7, 16, 17). This difference, in turn, suggests that a traditional inflammatory response may play a central role in the pathogenesis of EE but not necessarily in NERD.

The observed differences in infiltration of immune cells into the esophageal mucosa may be triggered by various factors. In this investigation a significant increase in LysoPAF-AT mRNA was observed in biopsies of EE patients, when compared to NERD patients. In rabbit esophageal mucosa exposed to HCl, an increase in PAF production contributes to migration and activation of peripheral blood leukocytes, supporting a role of this mediator in acid-induced epithelial injury (15).

PAF is known to induce migration of immune cells, and may be critical in the pathogenesis of EE (23, 29). It can be generated by two biosynthetic pathways, the de novo pathway and the remodeling pathway. The remodeling pathway is mainly responsible for pathological conditions that generate PAF (30). In this pathway the PAF precursor Lyso-PAF, is synthesized by phospholipase A2 (14), removing arachidonic acid (AA) from a membrane phospholipid, and resulting in AA and 1-alkyl-phosphatidylcholine (lysoPAF). Lyso-PAF is converted to PAF by Lyso-PAF acetyl transferase (LysoPAF-AT) (14). An increase of amount and activity of LysoPAF-AT reflects an increased synthesis of PAF during inflammation (10,14).

Other chemokines present in mucosal biopsies from EE, but not from NERD patients, are known to induce immune cell migration, and may be involved in the pathophysiology of EE. IL-8, the most powerful neutrophil chemoattractant (31, 32) is overexpressed in the affected mucosa of GERD patients (17, 19–21). In agreement with previous reports, our results revealed an increasedIL-8 mRNA and protein expression in EE patients, when compared to controls and NERD patients. The finding of enhanced levels of IL-8 protein, not only of mRNA expression, in the EE biopsies is important, as it shows that levels of the biologically active molecules are increased. Indeed, our results are not in agreement with previous investigations in which the increased IL-8 expression was also detected in esophageal biopsies of NERD patients. However, most of these studies showed mRNA level of IL-8 not providing data on protein expression, which better prove the presence of bioactivity (16, 21, 22). Moreover, increased IL-8 levels in the esophageal mucosa have been reported to correlate with endoscopic and histological severity of disease (20–22) and to decrease after treatment with PPIs (33) and following anti-reflux surgery (34), thus suggesting a role played by this chemokine in the mucosal injury. This is also supported by a recent multicenter, randomized, controlled trial including 514 patients affected by GERD. The study found that “microscopic esophagitis” (basal cell hyperplasia, dilatation of intercellular spaces, papillar elongation), was found in about 2/3 of NERD patients and in more than 90% of EE patients (18), but a significant immune cells infiltrate was not observed in NERD patients.

In addition, in the biopsies from EE patients, an up-regulation of eotaxin-1 mRNA and protein, and eotaxin-2 and -3 mRNA was observed. Eotaxins are recognized chemoattractants for eosinophils, basophils and mast cells (35–36). The evidence of increased in mRNA levels of eotaxins was previously shown in patients affected by eosinophilic esophagitis and, also, in GERD, even though at lower levels than in eosinophilic esophagitis (37–39). In the biopsies from EE patients, the data also show an increase in MCP-1 mRNA and protein and in MIP-1αmRNA. MCP-1 and MIP-1α are involved primarily in recruitment of monocytes and macrophages (40, 41). In our study we selected these chemokines because even in an animal model of chronic esophagitis, a significant increased expression of several inflammatory mediators, among which IL-1 β, TNF-α, MCP-1 and MIP-1 α, was detected in esophageal lesions compared with normal esophagus (42). The presence of mononuclear cells in the esophageal lamina propria, but not in the epithelium, is indicative of EE (43–45). Production of these chemoattractants by the esophageal epithelial cells following acid exposure may promote monocyte recruitment, which is maybe difficult to assess in bioptic sample, not sufficiently deep to contain a significant amount of lamina propria (44). Isomoto et al, using Cox’s proportional hazard regression model, have previously demonstrated a significantly positive association between the esophageal mucosal levels of some of these inflammatory mediators, particularly IL-1β and MCP-1, and symptoms recurrence in NERD patients (46). As the authors suggest, further investigations are needed to better understand the interplay between the hypersensitivity and esophageal inflammation mediated by enhanced production of inflammatory mediators.

Our results therefore are in agreement with recent findings supporting a cytokine mediated mechanism rather than a direct effect of gastroesophageal reflux in the induction of mucosal injury in EE (17).

An important finding of this study is that, different from EE patients, esophageal mucosa of NERD patients exhibited mRNA levels of all measured mediators comparable to asymptomatic controls. This observation again reinforces the notion that inflammatory mechanisms do not appear to play a central role in NERD pathogenesis.

A limitation of our study is the lack of pH-metry evaluation, as in the present series we have pH-metry findings in a minority of patients. However, only patients with a good response to PPIs (according to the symptom score of the QOLRAD questionnaire, before and following treatment) therefore, according to the Rome criteria, not functional heartburn patients, were studied. Furthermore we have previously demonstrated that no significant correlation was found between AET values and expression of TRPV1 in both ERD and NERD patients (7). These previous findings strongly support the role of TRPV1 receptors in the pathogenesis of typical symptoms in NERD patients, irrespective of duration of the esophageal acid exposure.

It’s conceivable that, despite similarities in NERD and EE concerning the increased expression of TRPV1 receptors (7), likely responsible for similar reflux-related symptoms, a different production of neurotransmitters and/or inflammatory mediators is involved in the pathogenesis of these two GERD phenotypes; further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying pathway, in order to identify new therapeutical strategies in both these pathological conditions. Increased density of TRPV1 receptors may therefore account for increased sensitivity to acid reflux causing release of ATP, that is involved in inflammation and pain transmission (11, 47–49). In addition, TRPV1-induced ATP release causes release of substance P and CGRP from submucosal neurons (8, 9) that could be involved in the symptoms genesis, and increases the activity of LysoPAF-AT (9), the enzyme responsible for PAF production. It is tempting to hypothesize that there is an “intrinsic”, different vulnerability of the esophageal mucosal barrier, possibly genetically determined, responsible for the different epithelial reaction to acid exposure in ERD, compared to NERD patients.

In summary, the infiltration of inflammatory cells observed in biopsies from EE patients and not in NERD biopsies may result from differences in the upregulation of chemokines observed in these two patient categories. Biopsies from NERD patients lack the elevated levels of chemokines that are known to attract the leukocyte subsets observed in patients with EE. Infiltration of these leukocytes into the esophageal mucosa may ultimately be responsible for the macroscopic mucosal injury.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, USA (NIDDK RO1 57030).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES AND COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Authors contributions:

A. Altomare and J. Ma: performed the research, analysed the data and wrote the paper.

L. Cheng: performed the ELISA measurements and analysed the data.

M. Guarino and M. Ribolsi collected the biopsies of the patients and revised the manuscript.

J. Ma., P. Biancani and K. Harnett contributed essential reagents or tools.

P. Biancani, K. Harnett and M. Cicala designed the research study and performed a critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

F. Rieder and C. Fiocchi contributed to design the project with constructive suggestions and performed a critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

All the authors approved the submitted and final versions.

References

- 1.Camilleri M, Dubois D, Coulie B, et al. Prevalence and socioeconomic impact of upper gastrointestinal disorders in the United States: results of the US Upper Gastrointestinal Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:543–552. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Locke GR, 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448–56. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710–717. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.051821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fass R, Ofman JJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease--should we adopt a new conceptual framework? Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1901–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong D. Endoscopic evaluation of gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Yale J Biol Med. 1999;72:93–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knowles CH, Aziz Q. Visceral hypersensitivity in non-erosive reflux disease. Gut. 2008;57:674–83. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.127886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guarino MP, Cheng L, Ma J, et al. Increased TRPV1 gene expression in esophageal mucosa of patients with non-erosive and erosive reflux disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:746–51. e219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma J, Altomare A, Rieder F, Behar J, Biancani P, Harnett KM. ATP: a mediator for HCl-induced TRPV1 activation in esophageal mucosa. American J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301:G1075–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00336.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng L, de la Monte S, Ma J, et al. HCl-activated neural and epithelial vanilloid receptors (TRPV1) in cat esophageal mucosa. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G135–43. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90386.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma J, Altomare A, de la Monte S, et al. HCl-induced inflammatory mediators in esophageal mucosa increase migration and production of H2O2 by peripheral blood leukocytes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G791–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00160.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertrand PP. ATP and sensory transduction in the enteric nervous system. Neuroscientist. 2003;9:243–60. doi: 10.1177/1073858403253768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burnstock G. Purines and sensory nerves. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2009;194:333–92. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-79090-7_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato M, Kita H, Tachibana A, Hayashi Y, Tsuchida Y, Kimura H. Dual signaling and effector pathways mediate human eosinophil activation by platelet-activating factor. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2004;134:37–43. doi: 10.1159/000077791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shindou H, Hishikawa D, Nakanishi H, et al. A single enzyme catalyzes both platelet-activating factor production and membrane biogenesis of inflammatory cells. Cloning and characterization of acetyl-CoA:LYSO-PAF acetyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6532–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paterson WG, Kieffer CA, Feldman MJ, Miller DV, Morris GP. Role of platelet-activating factor in acid-induced esophageal mucosal injury. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1861–6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isomoto H, Saenko VA, Kanazawa Y, et al. Enhanced expression of interleukin-8 and activation of nuclear factor kappa-B in endoscopy-negative gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:589–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Souza RF, Huo X, Mittal V, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux might cause esophagitis through a cytokine-mediated mechanism rather than caustic acid injury. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1776–84. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiocca R, Mastracci L, Engstrom C, et al. Long-term outcome of microscopic esophagitis in chronic GERD patients treated with esomeprazole or laparoscopic antireflux surgery in the LOTUS trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1015–23. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzgerald RC, Onwuegbusi BA, Bajaj-Elliott M, Saeed IT, Burnham WR, Farthing MJ. Diversity in the oesophageal phenotypic response to gastro-oesophageal reflux: immunological determinants. Gut. 2002;50:451–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.4.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isomoto H, Wang A, Mizuta Y, et al. Elevated levels of chemokines in esophageal mucosa of patients with reflux esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:551–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshida N, Uchiyama K, Kuroda M, et al. Interleukin-8 expression in the esophageal mucosa of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:816–22. doi: 10.1080/00365520410006729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monkemuller K, Wex T, Kuester D, et al. Interleukin-1beta and interleukin-8 expression correlate with the histomorphological changes in esophageal mucosa of patients with erosive and non-erosive reflux disease. Digestion. 2009;79:186–95. doi: 10.1159/000211714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okada S, Kita H, George TJ, Gleich GJ, Leiferman KM. Transmigration of eosinophils through basement membrane components in vitro: synergistic effects of platelet-activating factor and eosinophil-active cytokines. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;16:455–63. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.16.4.9115757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sigal CE, Valone FH, Holtzman MJ, Goetzl EJ. Preferential human eosinophil chemotactic activity of the platelet-activating factor (PAF) 1–0-hexadecyl-2-acetyl-sn-glyceryl-3-phosphocholine (AGEPC) J Clin Immunol. 1987;7:179–84. doi: 10.1007/BF00916012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lampinen M, Carlson M, Hakansson LD, Venge P. Cytokine-regulated accumulation of eosinophils in inflammatory disease. Allergy. 2004;59:793–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamouse-Smith ES, Furuta GT. Eosinophils in the gastrointestinal tract. Current gastroenterology reports. 2006;8:390–5. doi: 10.1007/s11894-006-0024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiklund IK, Junghard O, Grace E, et al. Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia patients. Psychometric documentation of a new disease-specific questionnaire (QOLRAD) Eur J Surg Suppl. 1998;583:41–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Modlin IM, Hunt RH, Malfertheiner P, et al. Diagnosis and management of non-erosive reflux disease--the Vevey NERD Consensus Group. Digestion. 2009;80:74–88. doi: 10.1159/000219365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wardlaw AJ, Moqbel R, Cromwell O, Kay AB. Platelet-activating factor. A potent chemotactic and chemokinetic factor for human eosinophils. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:1701–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI112765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snyder F. Platelet-activating factor and its analogs: metabolic pathways and related intracellular processes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1254:231–49. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)00192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harada A, Sekido N, Akahoshi T, Wada T, Mukaida N, Matsushima K. Essential involvement of interleukin-8 (IL-8) in acute inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56:559–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zwahlen R, Walz A, Rot A. In vitro and in vivo activity and pathophysiology of human interleukin-8 and related peptides. Int Rev Exp Pathol. 1993;34:27–42. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-364935-5.50008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isomoto H, Nishi Y, Kanazawa Y, et al. Immune and Inflammatory Responses in GERD and Lansoprazole. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2007;41:84–91. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.2007012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oh DS, DeMeester SR, Vallbohmer D, et al. Reduction of interleukin 8 gene expression in reflux esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus with antireflux surgery. Arch Surg. 2007;142:554–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.6.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rankin SM, Conroy DM, Williams TJ. Eotaxin and eosinophil recruitment: implications for human disease. Mol Med Today. 2000;6:20–7. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(99)01635-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Badewa AP, Hudson CE, Heiman AS. Regulatory effects of eotaxin, eotaxin-2, and eotaxin-3 on eosinophil degranulation and superoxide anion generation. Exp Biol Med. 2002;227:645–51. doi: 10.1177/153537020222700814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhattacharya B, Carlstein J, Sabo E, et al. Increased expression of eotaxin-3 distinguishes between eosinophilic esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux diseases. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1744–53. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blanchard C, Stucke EM, Rodriguez-Jimenez B, et al. A striking local esophageal cytokine expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:208–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang JJ, Joh JW, Fuentebella J, et al. Eotaxin and FGF enhance signaling through an extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK)-dependent pathway in the pathogenesis of Eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2010;6:25. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-6-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baggiolini M, Loetscher P, Moser B. Interleukin-8 and the chemokine family. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1995;17:103–8. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(94)00088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mukaida N, Harada A, Yasumoto K, Matsushima K. Properties of pro-inflammatory cell type-specific leukocyte chemotactic cytokines, interleukin 8 (IL-8) and monocyte chemotactic and activating factor (MCAF) Microbiol Immunol. 1992;36:773–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1992.tb02080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamaguchi M, Fujiwara Y, Yakashima T, et al. Increased expression of cytochines and adhesion molecules in rat chronic esophagitis. Digestion. 2003;68:189–197. doi: 10.1159/000075698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ismail-Beigi F, Horton PF, Pope CE., 2nd Histological consequences of gastroesophageal reflux in man. Gastroenterology. 1970;58:163–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kobayashi S, Kasugai T. Endoscopic and biopsy criteria for the diagnosis of esophagitis with a fiberoptic esophagoscope. Am J Dig Dis. 1974;19:345–52. doi: 10.1007/BF01072525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frierson HF., Jr Histology in the diagnosis of reflux esophagitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1990;19:631–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barlow WJ, Orlando RC. The pathogenesis of heartburn in nonerosive reflux disease: a unifying hypothesis. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:771–778. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bertrand PP, Bornstein JC. ATP as a putative sensory mediator: activation of intrinsic sensory neurons of the myenteric plexus via P2X receptors. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4767–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-04767.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burnstock G. Purinergic mechanosensory transduction and visceral pain. Molecular pain. 2009;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mihara H, Boudaka A, Sugiyama T, Moriyama Y, Tominaga M. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4)-dependent calcium influx and ATP release in mouse oesophageal keratinocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 2011;589:3471–82. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.207829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]