Abstract

Objective

To describe out-of-pocket costs of inpatient care for children under 5 years of age in district hospitals in Kenya.

Methods

A total of 256 caretakers of admitted children were interviewed in 2-week surveys conducted in eight hospitals in four provinces in Kenya. Caretakers were asked to report care seeking behaviour and expenditure related to accessing inpatient care. Family socio-economic status was assessed through reported expenditure in the previous month.

Results

Seventy eight percent of caretakers were required to pay user charges to access inpatient care for children. User charges (mean, US$ 8.1; 95% CI, 6.4–9.7) were 59% of total out-of-pocket costs, while transport costs (mean, US$ 4.9; 95% CI, 3.9–6.0) and medicine costs (mean, US$ 0.7; 95% CI, 0.5–1.0) were 36% and 5%, respectively. The mean total out-of-pocket cost per paediatric admission was US$ 14.1 (95% CI, 11.9–16.2). Out-of-pocket expenditures on health were catastrophic for 25.4% (95% CI, 18.4–33.3) of caretakers interviewed. Out-of-pocket expenditures were regressive, with a greater burden being experienced by households with lower socio-economic status.

Conclusion

Despite a policy of user fee exemption for children under 5 years of age in Kenya, our findings show that high unofficial user fees are still charged in district hospitals. Financing mechanisms that will offer financial risk protection to children seeking care need to be developed to remove barriers to child survival.

Keywords: user fees, out-of-pocket costs, child health, hospitals

Introduction

Access to hospital care plays an important role in improving child survival (Schellenberg et al. 2004), and costs have been identified as a significant barrier to access (Perkins et al. 2009). In Kenya, public hospitals operate on a cost-sharing arrangement, where the government provides healthcare services at a subsidised rate, financed by central government budgetary allocations to health and supplemented by out-of-pocket payments from users (Management science for health 2001). The cost-sharing policy provides for exemptions of user charges for children under the age of 5 (Carrin et al. 2007). Experience in developing countries shows that policies on removal of user fees or exemptions are often poorly implemented (Chuma et al. 2009). We examined out-of-pocket payments incurred by caretakers arising from inpatient episodes and explored their magnitude in relation to household expenditures on essential items so as to determine whether out-of-pocket expenditures were catastrophic.

Methods

The study was conducted in 2008 as part of a larger study to improve the quality of paediatric inpatient care in district hospitals in Kenya (Ayieko et al. 2011). Data were collected prospectively, in a survey over 2 weeks, by administering a questionnaire to caretakers of children admitted in eight district hospitals in Kenya. The sampling and selection of hospitals has been described elsewhere (Ayieko et al. 2011). We interviewed 256 caretakers (range, 23–36 per hospital). For this descriptive analysis, the data from the eight hospitals were pooled. Total out-of-pocket costs were defined as the sum of transport costs to and from the hospital, user fees and any charges levied for medicines and laboratory services. Caregivers were asked to recall household expenditures they incurred in the previous month. Households were considered to have incurred catastrophic expenditures if their total out-of-pocket costs exceeded 40% of their monthly non-subsistence expenditure (Xu et al. 2003). Households were grouped into socio-economic quintiles (1 = lowest to 5 = highest) and two broader groups, higher and lower socio-economic status, based on household monthly expenditures. Out-of-pocket costs and household expenditures were converted from Kenya shillings to US dollars and inflated to 2010 prices using GDP deflators for Kenya. The data were skewed, and so, we explored presenting them as medians and interquartile ranges. Household expenditure categories (rent, food and education) and out-of-pocket cost categories (medicine, transport and user charges) were heavily zero-inflated and hence could only meaningfully be presented as means. Total out-of-pocket costs are presented as both means and medians with non-parametric tests used to test for associations.

Results

The characteristics of the admitted children are shown in Table 1. The median time of the journey to the hospital by caregivers and the sick children under their care was 45 min (IQR, 30–105). 79.7% (95% CI, 74.2–84.5) of the caregivers used public means to get to hospital while 18.3% (95% CI, 13.7–23.7) walked to the hospital and 2.0% (95% CI, 0.6–4.6) used private means. The median number of visits to a healthcare provider before the child was admitted was 3 (IQR, 1–6).

Table 1.

Characteristics of admitted children

| Age | (n) Observations | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age in months | 184 | 11.6 (5.2–24.9) |

| Proportion (95% CI) | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | (249) 128 | 51.4% (45.0–57.8) |

| Female | (249) 121 | 48.6% (42.2–56.0) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Malaria | (256) 162 | 63.3% (57.1–69.2) |

| Pneumonia | (256) 124 | 40.6% (34.6–46.9) |

| Diarrhoea and dehydration | (256) 72 | 28.1% (23.4–34.9) |

| Other | (256) 24 | 9.38% (6.10–13.63) |

| Socio-economic status | ||

| Higher socio-economic group | (250) 123 | 49.2% (42.8–55.8) |

| Lower socio-economic group | (250) 127 | 50.8% (44.4–57.2) |

| Employment status of caregivers | ||

| Formal employment | (251) 60 | 23.9% (18.8–29.7) |

| Informal/unemployed | (251) 191 | 76.1% (70.3–81.2) |

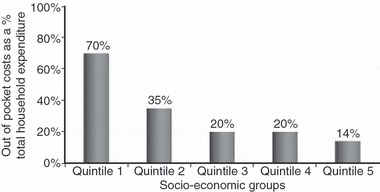

Household monthly expenditure on food was 79% of the total monthly expenditure on essentials (food, rent and education); expenditures on rent constituted 11%, and on education 10% (Table 2). The majority of caretakers interviewed (77.7% (95% CI, 72.1–82.7)) reported paying user fees for admission care of sick children. 66.7% (95% CI, 59.3–73.4) used their savings to meet hospital out-of-pocket costs, and 33.3% (95% CI, 26.6–40.7) borrowed money. User charges contributed to the greatest proportion (59%) of out-of-pocket costs, followed by transport (36%) and medicine (5%). Table 3 shows hospitalization expenditure. Figure 1 shows the relationship between out-of-pocket expenditures and their burden (out-of-pocket expenditure as a percentage of total household expenditure) and socio-economic quintiles. Non-parametric tests showed that the household out-of-pocket costs were significantly higher in lower socio-economic strata households (median US$ 11.0 (IQR (4.7–19.3)) than in higher socio-economic strata households (median, US$ 7.0 (IQR, 2.6–14.2)) (rank sum P = 0.025) but did not vary significantly with diagnosis. Out-of-pocket costs were catastrophic for 25.4% (95% CI, 18.4–33.3) of households. The proportion of catastrophic health expenditures was higher in households in the lower socio-economic group (41.3% (95% CI, 29.0%–54.4%)) than in the higher socio-economic group (11.5% (95% CI, 5.4%–20.7%)).

Table 2.

Household monthly expenditures

| Expenditure category | Number of caretakers | As% of total expenditure | Mean expenditure US$ (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food* | 250 | 79 | 56.2 (52.0–60.5) |

| Education | 181 | 10 | 6.8 (4.5–9.2) |

| Rent | 154 | 11 | 8.2 (3.8–12.5) |

| Total expenditure | 250 | 66.2 (60.7–71.7) |

Does not include self-produced food.

Table 3.

Out-of-pocket expenditures associated with inpatient care for children

| Cost category | Observations | Median US$ (IQR) | Mean US$ (95% CI) | As % of total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transport costs | 246 | 4.9 (3.9–6.1) | 36 | |

| Medicine costs | 254 | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | 5 | |

| User charges | 254 | 8.1 (6.4–9.7) | 59 | |

| Total in-patient out-of-pocket costs | 244 | 7.9 (3.8–17.2) | 14.1 (11.9–16.2) | |

| Out-of-pocket costs as a percentage of total household expenditure | 238 | 36.5% (27.4–45.5) | ||

| Proportion of households with catastrophic expenditures | 142 | 25.4 (95% CI 18.4–33.3) |

Figure 1.

Relationship between out-of-pocket expenditure burden and socio-economic status. (Social-economic status is represented by socio-economic quintiles: Quintile 1 represents the lowest socio-economic group while 5 represents the highest).

Discussion

Our findings show that 78% of caretakers paid user fees for inpatient paediatric care for sick children. The mean out-of-pocket costs for inpatient paediatric care were US$ 14.1 (95%CI 11.9–16.2), which is almost three times higher than reported out-of-pocket costs for district hospital paediatric inpatient care in Tanzania (US$ 5.5) (Saksena et al. 2010). Given that children under 5 years of age are officially exempted from user fees in public health facilities in Kenya, it is apparent that this policy is not well implemented in practice. The violation of the user fee exemption policy in Kenya has been reported in previous studies (Ayieko et al. 2009; Chuma et al. 2009), with funding gaps given as a reason for this violation (Chuma et al. 2009). The poor implementation of exemption and waiver mechanisms within cost-sharing policies is likely to introduce inequities in access to child health.

The mean percentage of out-of-pocket costs to total household expenditure on essentials was 36.5% (95% CI 27.4–45.5). This level of healthcare expenditure is arguably high and comparable to findings in Tanzania of 35.4% (Saksena et al. 2010). A cost burden >40% of household non-subsistence expenditure is likely to be catastrophic to the household (Xu et al. 2003). Based on this definition, out-of-pocket expenditures on health were catastrophic for 25.4% (95% CI, 18.4–33.3) of caretakers interviewed. The mean percentage of out-of-pocket costs to non-subsistence household expenditure was 46.9% (95% CI, 28.5–65.2). When households were divided into 2 socio-economic groups, catastrophic costs were incurred by 41.3% (95% CI, 29.0–54.4) in the lower socio-economic group and 11.5% (95% CI, 5.4–20.8) in the higher socio-economic group. As expected, out-of-pocket expenditures in these households appear to be regressive with a greater burden being experienced by households in lower socio-economic groups given that their capacity to pay is diminished compared to households in higher socio-economic groups (Figure 1).

This study has a number of limitations. Data on household monthly expenditures depend on recalled expenditure over a period of a month and are subject to recall biases. Out-of-pocket costs reported are lower than actual costs, given that we did not collect information on other direct costs (e.g. expenses for food and upkeep of any accompanying relatives). The study also only focused on out-of-pocket costs associated with hospital admissions and left out costs associated with outpatient visits and with those who did not seek care in hospitals; these costs would be important in giving a comprehensive picture of out-of-pocket healthcare costs associated with child illnesses. Also, whereas catastrophic health expenditures are conventionally calculated based on annual health expenditure and annual consumption expenditure, the data available allowed for a calculation based on monthly household and health expenditures. These limitations notwithstanding the data presented are potentially useful as inputs in costing and/or cost-effectiveness models that require patient cost and suggest there are significant-out-of pocket costs associated with paediatric admission care in district hospitals in Kenya, which offer a barrier to access to care.

Policy makers need to mitigate the adverse effects of such expenditures, for example, by extending insurance coverage to the uninsured or by increasing efforts to implement exemption mechanisms. Our findings reinforce observations of tension between policy makers and health facility managers in resource-limited settings, with managers trying to provide services with limited resources and hence forced to disregard policies that threaten their revenue streams.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the staff of all the hospitals included in the study and colleagues from the Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, the Ministry of Medical Services and the KEMRI/Wellcome Trust Programme for their assistance in the conduct of this study. This work is published with the permission of the Director of KEMRI and was funded by the Wellcome Trust.

References

- Ayieko P, Akumu AO, Griffiths UK, English M. The economic burden of inpatient paediatric care in Kenya: household and provider costs for treatment of pneumonia, malaria and meningitis. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation. 2009;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayieko P, Ntoburi S, Wagai J, et al. A multifaceted intervention to implement guidelines and improve admission paediatric care in Kenyan district hospitals: a cluster randomized trial. PLOS Medicine. 2011;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001018. e1001018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrin G, James C, Adelhardt M, Al E. Health financing reform in Kenya – assessing the social health insurance proposal. South African Medical Journal. 2007;97:130–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuma J, Musimbi J, Okungu V, Goodman C, Molyneux C. Reducing user fees for primary health care in Kenya: policy on paper or policy in practice? International Journal for Equity in Health. 2009;8:15. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Management science for health. A decade of cost sharing in Kenya: sharing the burden yields better health services, higher quality. In: MSH, editor. Boston, MA: Nairobi, Management Science for Health; 2001. pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins M, Brazier E, Themmen E, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for facility-based maternity care in three African countries. Health Policy Planning. 2009;24:289–300. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saksena P, Reyburn H, Njau B, Chonya S, Mbakilwa H, Mills A. Patient costs for paediatric hospital admissions in Tanzania: a neglected burden? Health Policy Planning. 2010;25:328–333. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellenberg JA, Adam T, Mshinda H, et al. Effectiveness and cost of facility-based Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) in Tanzania. Lancet. 2004;364:1583–1594. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17311-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Evans D, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray C. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet. 2003;362:111–117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13861-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]