Abstract

Eastern boundary currents are often described as ‘wasp-waist’ ecosystems in which one or few mid-level forage species support a high diversity of larger predators that are highly susceptible to fluctuations in prey biomass. The assumption of wasp-waist control has not been empirically tested in all such ecosystems. This study used stable isotope analysis to test the hypothesis of wasp-waist control in the southern California Current large marine ecosystem (CCLME). We analyzed prey and predator tissue for δ13C and δ15N and used Bayesian mixing models to provide estimates of CCLME trophic dynamics from 2007–2010. Our results show high omnivory, planktivory by some predators, and a higher degree of trophic connectivity than that suggested by the wasp-waist model. Based on this study period, wasp-waist models oversimplify trophic dynamics within the CCLME and potentially other upwelling, pelagic ecosystems. Higher trophic connectivity in the CCLME likely increases ecosystem stability and resilience to perturbations.

The California Current large marine ecosystem (CCLME) is one of the world's eastern boundary currents that undergo seasonal upwelling leading to high productivity1. The CCLME supports a large biomass of planktivorous lower trophic level (LTL) species such as sardine, anchovy, and small squids2, which support diverse predators such as tunas, billfish, seabirds, pinnipeds, sharks, and cetaceans3,4. Large-scale electronic tagging efforts (e.g., TOPP: Tagging of Pacific Predators) have revealed the importance of the CCLME to these highly migratory predators and demonstrated a high level of residency for many highly migratory species5,6,7. In the eastern Pacific Ocean, as in most other marine systems, highly migratory species (e.g., tunas) and LTLs (e.g., sardine) have been heavily fished and some have shown periodic population declines3,8,9. Although the populations of many of these species declined during periods of overfishing, many have subsequently rebounded in the CCLME. Trophic dynamics may affect population fluctuations, and assessing the strength of trophic linkages is important in forecasting the potential impacts of natural and human-induced declines in prey or predator populations.

In characterizing ecosystem trophic structure, it is important to understand whether dominant forcing mechanisms are bottom-up or top-down10. The effect of predator removal from pelagic ecosystems is contentious, but recent work suggests the possibility of top-down effects of predators even in open-ocean systems11. Conversely, bottom-up controls also likely affect predator feeding success and consequently, the extent of their residency in the CCLME12 and other upwelling ecosystems13. The interaction between top-down and bottom-up controls remains relatively poorly understood and difficult to test in productive upwelling ecosystems. Other models of ecological control in eastern boundary currents have been proposed, including ‘wasp-waist’ control as an alternative to classical bottom-up or top-down models13,14,15.

In wasp-waist (WW) systems, population dynamics are suggested to be largely controlled by LTLs rather than the bottom or the top. WW ecosystems are highly productive systems that support low diversity (one or few species) but high abundance of LTLs such as sardine and anchovy13,14,15. This large prey biomass supports a high diversity of marine mammals, teleosts, elasmobranchs, and seabirds. LTLs at the wasp-waist level exert top-down control on zooplankton and bottom-up control on top predators, with environmental factors largely affecting their abundance10,13. Ecosystem models have shown that WW upwelling systems are more vulnerable to collapse when forage fish decline due to the critical energetic links that LTLs provide between highly available zooplankton and larger predators16. However, recent studies have shown that in some eastern boundary currents (e.g., the northern California Current), trophic dynamics may be more complex, with predators feeding on multiple trophic levels including planktonic organisms (e.g., euphausiids)17, increasing ecosystem stability18. Characterizing a system as WW (or under different controls) thus requires the acquisition of diet information for predators within a system.

The primary tool to identify trophic linkages has traditionally been directly through gut content analysis of predators19. Gut content analysis is an important tool to identify dominant prey species in predator diets. However, these analyses are limited to feeding data during the timeframe(s) of predator sample availability, and may overemphasize the importance of large prey or prey with hard parts, which tend to accumulate in the stomachs of predators19. Stable isotope analysis (SIA) is a newer ecological tool to study predator diets that provides longer-term estimates of the primary prey that are incorporated into predator tissue. SIA is time-integrated, non-lethal, and significantly faster than gut content analysis20, and it is particularly powerful when combined with the specific prey information that stomach contents can provide.

SIA of carbon and nitrogen isotopes, the elements most commonly used in ecological studies, measures the ratio of a heavier, rare isotope to a lighter, more common isotope (13C:12C or δ13C;15N:14N or δ15N) expressed as parts per mille (‰) relative to a standard. Stable isotope values increase stepwise up food webs due to preferential retention of the heavier isotope in consumer tissues during metabolic processes; the subsequent difference between the isotope values of consumer and prey is the trophic discrimination factor (TDF). δ13C values are often used to infer different baseline sources (e.g. phytoplankton vs. macroalgae), as primary producers in discrete ecosystems may have dissimilar δ13C values that will change minimally through food webs20. In contrast, δ15N values have generally been used to estimate trophic level due to the higher increase of δ15N values with each trophic step in food webs20,21.

The stable isotope ratios of predator tissues reflect an integrated value of prey consumed over time. If prey isotope values are sufficiently different, relative proportions of dietary inputs can be estimated from predator isotope values using Bayesian mixing models22,23,24 that take uncertainty in prey values and trophic discrimination factors into account when estimating predator diets. With adequate sampling of predators, potential prey, and TDF values of predators, SIA becomes a powerful tool to study trophic interactions to an extent that is unfeasible using gut content analysis alone.

We used SIA to test whether the trophic dynamics of the CCLME were consistent with those hypothesized by the wasp-waist model. Specifically we asked the question: do predators in the southern CCLME rely predominantly on a few forage species at the wasp waist level? Alternatively, are there inter-specific differences in predator foraging and diversity of diet? Results show the degree to which predators rely on, and exploit, certain prey groups. Thus these results have implications for management of both predator and prey species in the CCLME25. They also suggest the underlying mechanisms that dictate trophic dynamics in the CCLME, which is crucial for understanding and predicting changes in this pelagic ecosystem over time.

Results

We obtained tissue samples from 30 species from the southern CCLME from 2007–2010 (17 predator and 13 prey; Fig. 1 and Table 1) and analyzed 292 individual predators and 181 individual prey for δ13C and δ15N (Table 1). Prey species sampled from predator stomachs indicated that predators fed on a wide range of prey, including forage fishes (saury, sardine, jack mackerel, juvenile rockfish) mesopelagic species (myctophids, eelpouts, barracudinas), rocky-reef associated wrasses (señoritas), epipelagic crustaceans (pelagic red crabs), and cephalopods (argonauta, gonatid, onychoteuthid, market, and jumbo squids) (Table 1).

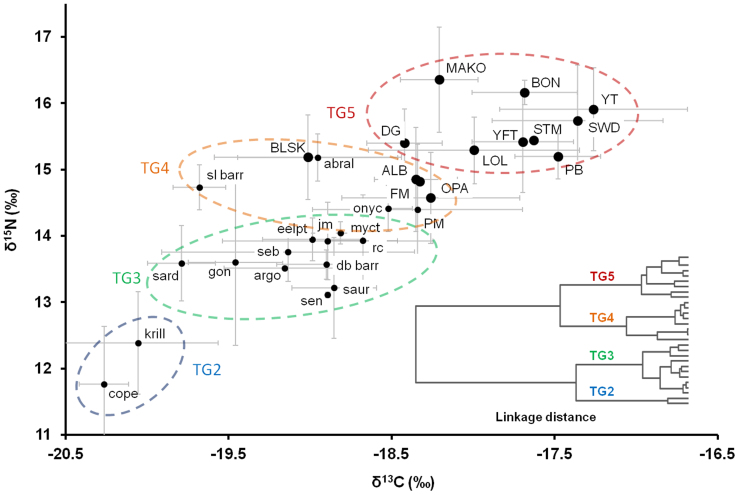

Figure 1. Biplot of δ13C and δ15N values (mean ± SD) for predators (caps labels,  ) and prey (lowercase labels,

) and prey (lowercase labels,  ).

).

Large ovals show trophic groups (TG2-5) from cluster analysis by color. Species are abbreviated as in Table 1. Inset shows dendrogram of cluster analysis; each node represents an individual species.

Table 1. Table of all predator and prey species sampled in this study, separated by trophic group (TG2 – 5). Mean (± SD) δ13C and δ15N values are for white muscle for all species except crustaceans (analyzed whole). δ13C values are arithmetically lipid-corrected according to Logan et al. 2008.

| Species | Common name | Code | Mean δ13C (SD) | Mean δ15N (SD) | Mean length (SD) (cm) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trophic Group 5 | ||||||

| Isurus oxyrinchus | mako shark | MAKO | −18.21 (0.24) | 16.36 (0.80) | 109.8 (17.9) | 10 |

| Sarda chiliensis | bonito | BON | −17.68 (0.32) | 16.16 (0.18) | 47.8 (0.6) | 12 |

| Seriola lalandi | yellowtail jack | YT | −17.26 (0.57) | 15.90 (0.62) | 73.7 (13.0) | 34 |

| Tetrapturus audax | striped marlin | STM | −17.63 | 15.44 | 215.9 | 1 |

| Xiphias gladius | swordfish | SWD | −17.36 (1.17) | 15.74 (0.80) | 135.2 (29.4) | 21 |

| Thunnus orientalis | Pacific bluefin tuna | PBFT | −17.48 (0.26) | 15.20 (0.34) | 84.8 (3.1) | 42 |

| Thunnus albacares | yellowfin tuna | YFT | −17.70 (0.31) | 15.42 (0.77) | 77.6 (9.7) | 64 |

| Dosidicus gigas | jumbo squid | DG | −18.42 (0.23) | 15.40 (0.52) | 22.4 (4.3) | 17 |

| Loligo opalescens | market squid | LOL | −17.99 (0.65) | 15.29 (0.50) | 4.2 (1.5) | 21 |

| Trophic Group 4 | ||||||

| Lampris guttatus | opah | OPA | −18.26 (0.55) | 14.57 (0.69) | 97.2 (3.7) | 4 |

| Prionace glauca | blue shark | BLSK | −19.01 (0.57) | 15.19 (0.64) | 111.2 (31.8) | 9 |

| Thunnus alalunga | albacore tuna | ALB | −18.35 (0.26) | 14.85 (0.79) | 86.0 (8.2) | 61 |

| Auxis thazard | frigate mackerel | FM | −18.32 | 14.82 | nd | 1 |

| Scomber japonicus | Pacific mackerel | PM | −18.34 (0.64) | 14.40 (0.98) | 18.6 (1.9) | 16 |

| Abraliopsis spp. | squid | ABRL | −18.95 (0.49) | 15.18 (0.36) | 1.9 (0.3) | 4 |

| Lestidiops ringens | slender barracudina | SL BARR | −19.68 (0.16) | 14.73 (0.34) | nd | 5 |

| Onychoteuthis spp. | clubhook squid | ONYC | −18.52 (0.15) | 14.41 (0.34) | 10.3 (1.4) | 6 |

| Trophic Group 3 | ||||||

| Sardinops sagax | sardine | SARD | −19.79 (0.21) | 13.59 (0.57) | 8.2 (1.5) | 18 |

| Cololabis saira | saury | SAUR | −18.85 (0.26) | 13.21 (0.76) | 9.2 (3.1) | 20 |

| Trachurus symmetricus | jack mackerel | JM | −18.89 (0.65) | 13.92 (0.58) | 7.9 (2.8) | 27 |

| Gonatopsis spp. | gonatid squid | GON | −19.46 (0.29) | 13.61 (1.25) | 7.9 (1.8) | 7 |

| Sebastes juv. | rockfish juveniles | SEB | −19.14 (0.78) | 13.76 (0.44) | 6.2 (4.0) | 7 |

| Oxyjulis californica | señorita | SEN | −18.89 (0.01) | 13.11 (0.04) | 17.8 (0.4) | 2 |

| Melanostigma pammelas | midwater eelpout | EELPT | −18.98 (0.31) | 13.94 (0.32) | 7.2 (1.0) | 8 |

| Magnisudis atlantica | duckbill barracudina | DB BARR | −18.90 (0.31) | 13.57 (0.22) | 28.1 (5.7) | 5 |

| Argonauta spp. | argonauta | ARGO | −19.16 (0.37) | 13.51 (0.03) | 1.8 (0.4) | 2 |

| Pleuroncodes planipes | pelagic red crab | RC | −18.65 (0.21) | 13.99 (0.69) | 2.0 (0.1) | 5 |

| Myctophidae spp. | myctophid | MYCT | −18.81 (0.25) | 14.04 (0.17) | 5.6 (1.3) | 5 |

| Trophic Group 2 | ||||||

| Euphausidae spp. | krill | KRILL | −20.06 (0.49) | 12.39 (0.77) | 2.2 (0.3) | 14 |

| Copepoda | calanoid copepod | COPE | −20.26 (0.15) | 11.77 (0.87) | 0.1 (0) | 25 |

Cluster analysis resulted in separation of species into four trophic groups based on mean species δ13C and δ15N values (Fig. 1). These four groups were labeled, based on trophic ecology, as: zooplankton (TG2), planktivorous prey or LTLs (TG3), meso-predators (TG4), and upper trophic level predators (in this study, apex predators) (TG5). Linkage distances were relatively high between the four groups (Fig. 1 inset), suggesting that these trophic groups had distinct isotopic values. Hereafter these species groups will be referred to as TG2, TG3, TG4, and TG5 (see Table 1 for species included in each trophic group). TG3 represents LTLs at the wasp-waist trophic level of WW ecosystem models13.

The predominant planktivorous prey species (TG3) showed stepwise increases in δ13C and δ15N values relative to zooplankton (TG2), followed by meso-predators (TG4; onychoteuthid squids, Pacific mackerel, albacore, frigate mackerel, opah) (Fig. 1). The highest mean δ15N values were observed in mako sharks, yellowtail, bonito, jumbo squid, blue sharks, striped marlin, yellowfin, and bluefin tunas (TG5), though these species showed considerable range in mean δ13C values (−18.4‰ – −17.3‰; Table 1 and Fig. 1).

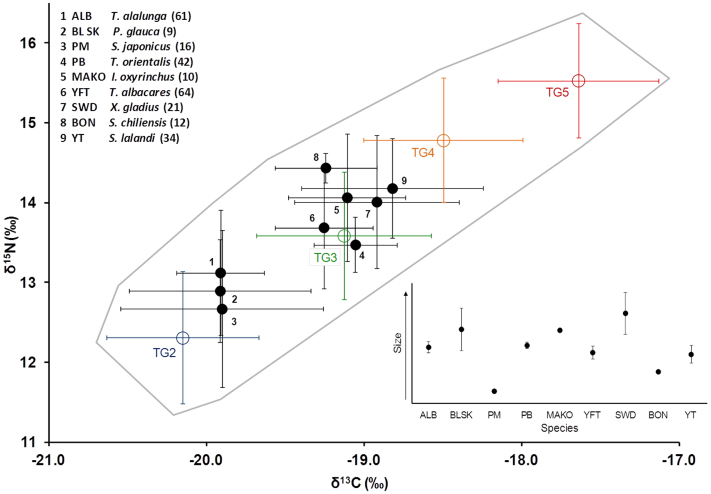

After TDF correction, two predator clusters were clearly discernible based on their position in isospace relative to prey inputs (Fig. 2). Of the nine predator species of adequate sample size to be included in this analysis, the three TG4 species (meso-predators) overlapped more closely with TG2 than TG3, though the TDF-corrected mean TG4 isotope values fell between the two groups (Fig. 2). The remaining six species, all apex predators (TG5), overlapped closely with TG3 (Fig. 2). Both clusters contained a range of predator sizes (Fig. 2 inset).

Figure 2. Biplot of δ13C and δ15N values (mean ± SD) for TGs 2–5 ( ) and TDF-corrected δ13C and δ15N values (mean ± SD) for nine predator species (

) and TDF-corrected δ13C and δ15N values (mean ± SD) for nine predator species ( ), numerically labeled as shown.

), numerically labeled as shown.

Sample size for each species shown in parentheses. Predators are adjusted for TDFs for δ15N and δ13C according to PB TDFs from Madigan (submitted) (PM, BON, ALB, YT, PB, YFT: Δ15N = 1.85, Δ13C = 1.83‰) or Hussey et al. 2010 (MAKO, BLSK: Δ15N = 4.0, Δ13C = 0.9‰). Grey outline encloses predator and prey isospace in the southern CCLME. Inset shows relative sizes (CFL ± SD) for nine species shown.

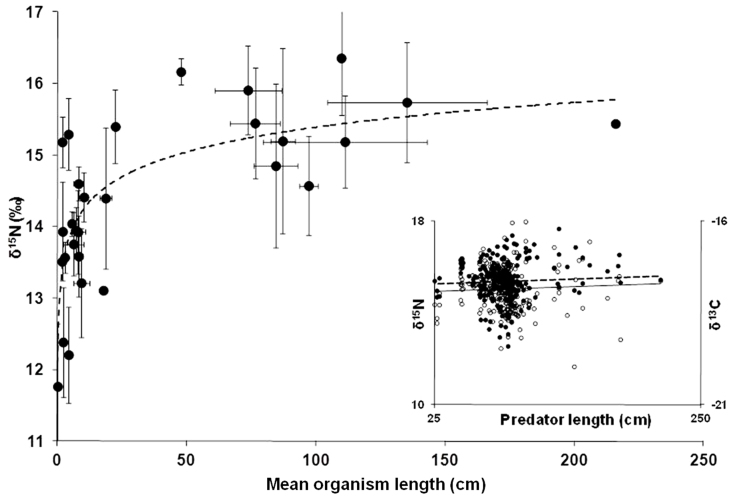

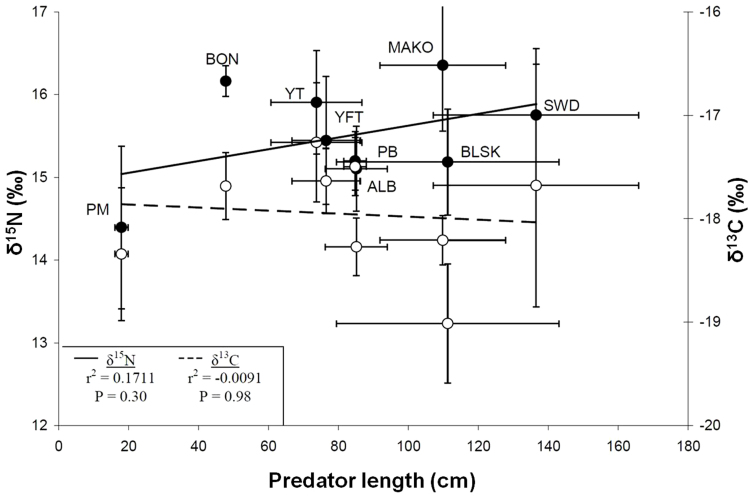

δ15N values increased rapidly with size in organisms <25 cm but there was strikingly little change with size between 25 and 250 cm (Fig. 3). Differences in mean δ13C and δ15N values of predators did not correspond with body size (Fig. 4). Linear fits showed a slightly negative trend of mean predator δ13C values (r2 = −0.0091) and a slightly positive trend of mean predator δ15N values (r2 = 0.1711) with mean predator size, though neither were statistically significant (P = 0.98, P = 0.30, respectively) (Fig. 4). Most individual species did not show significant change in δ13C and δ15N with size (S Fig 2 and Supplementary Table S1). Exceptions were jack mackerel and yellowtail in which δ13C and δ15N values increased with size, and Pacific bluefin tuna in which δ13C values increased and δ15N values decreased with size (Supplementary Fig. S2 and Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 3. Relationship between mean organism size and mean δ15N values for species sampled in this study.

Line represents logarithmic fit to data (δ15N = 0.4997*ln(size); r2 = 0.56). Inset shows relationship between length of individual meso- and higher level predators (>25 cm) and δ13C ( ) and δ15N (

) and δ15N ( ) values. Relationship between size and δ13C (δ13C = 0.0018(size) + 15.2; r2 = 0.0038) and δ15N (δ15N = 0.0011(size) − 17.9; r2 = 0.0026) are not significantly different from zero (P = 0.41 and 0.31, respectively).

) values. Relationship between size and δ13C (δ13C = 0.0018(size) + 15.2; r2 = 0.0038) and δ15N (δ15N = 0.0011(size) − 17.9; r2 = 0.0026) are not significantly different from zero (P = 0.41 and 0.31, respectively).

Figure 4. Relationship of predator size and isotope values.

For nine predator species δ13C ( ) and δ15N values (

) and δ15N values ( ) are shown against predator size (CFL in cm). All values are mean ± SD. Lines represent linear fits for size versus δ13C (- -) and size versus δ15N (—). Correlations were not significant at the α = 0.05 level (inset).

) are shown against predator size (CFL in cm). All values are mean ± SD. Lines represent linear fits for size versus δ13C (- -) and size versus δ15N (—). Correlations were not significant at the α = 0.05 level (inset).

Bayesian mixing models required prior assignments that gave TG3 (WW prey) threefold higher likelihood of importance [1 3 1 1] in predator diets to avoid bimodal solutions. This assumed WW feeding by all TG4 and TG5 predators, based on feeding studies in the CCLME26,27 and general WW ecosystem model assumptions13. Though this assumption places high emphasis on TG3, it makes results of non-TG3 feeding (i.e., non-WW) more compelling. However, median prey input estimates were similar for most species and TGs using uninformed priors or priors giving TG3 prey twice the importance of other prey ([1 2 1 1]) (Table 2 and Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). Furthermore, priors of [1 3 1 1] were only necessary to avoid bimodal results in bonito, yellowtail, and TG5 diet assessments (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Table 2. Estimated proportional prey inputs from Bayesian isotope mixing model (MixSir) of trophic groups (TG) to diets of nine predator species and to diets of trophic groups as a whole (TG3-5). Values reported are for 1×107 iterations and priors based on wasp-waist assumptions [1 3 1 1], as discussed in methods.

| Estimated proportional prey inputs | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trophic Group 2 | Trophic Group 3 | Trophic Group 4 | Trophic Group 5 | ||||||

| Species | Code | Median | 95% CI | Median | 95% CI | Median | 95% CI | Median | 95% CI |

| S. japonicus | PM | 89 | 83 – 95 | 7 | 3 – 14 | 1 | 0 – 4 | 0 | 0 – 4 |

| P. glauca | BLSK | 69 | 52 – 81 | 23 | 8 – 43 | 4 | 0 – 13 | 3 | 0 – 10 |

| T. alalunga | ALB | 75 | 70 – 79 | 12 | 5 – 23 | 12 | 4 – 18 | 1 | 0 – 4 |

| T. orientalis | PB | 43 | 36 – 49 | 32 | 21 – 42 | 17 | 6 – 27 | 9 | 2 – 17 |

| T. albacares | YFT | 52 | 46 – 57 | 5 | 2 – 16 | 41 | 10 – 45 | 2 | 0 – 8 |

| S. chiliensis | BON | 11 | 1 – 30 | 68 | 24 – 86 | 15 | 2 – 44 | 4 | 0 – 15 |

| S. lalandi | YT | 3 | 0 – 9 | 76 | 65 – 86 | 12 | 1 – 28 | 7 | 1 – 17 |

| X. gladius | SWD | 1 | 0 – 5 | 96 | 92 – 99 | 1 | 0 – 4 | 1 | 0 – 4 |

| I. oxyrinchus | MAKO | 4 | 0 – 14 | 85 | 73 – 94 | 5 | 0 – 15 | 4 | 0 – 12 |

| Trophic Group (TG) | |||||||||

| 5 | MAKO, YT, SWD, BON, YFT, PB, STM, LOL, DG | 23 | 19 – 29 | 63 | 57 – 69 | 5 | 0 – 14 | 8 | 1 – 13 |

| 4 | BLSK, ABRL, SLB, ALB, FM, OPA, PM, ONYC | 79 | 74 – 84 | 16 | 8 – 24 | 3 | 0 – 9 | 1 | 0 – 5 |

| 3 | SARD, EELPT, JM, SEB, ARGO, DBB, SAUR, SEN, MYCT, GON, RC | 99 | 98 – 99 | 1 | 0 – 1 | 0 | 0 – 1 | 0 | 0 – 1 |

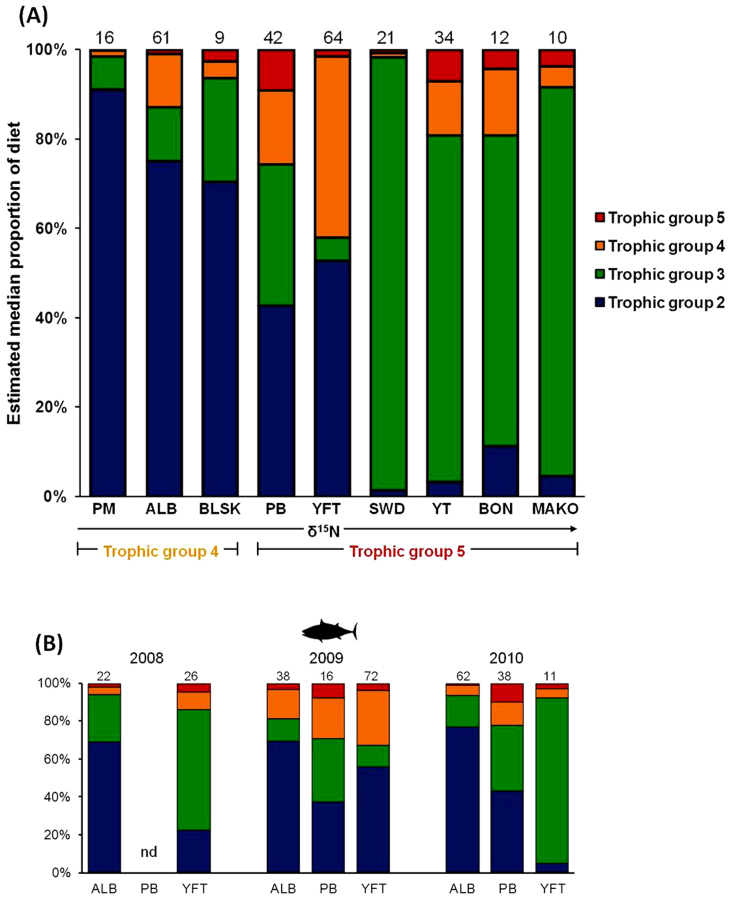

Mixing model results revealed three general feeding patterns for nine predator species within the two upper trophic groups (TG4 and TG5). TG4 predators exhibited a high utilization of TG2 (krill) (Pacific mackerel: 89%, albacore: 75%, and blue shark: 69%), whereas for TG5 predators there were two different patterns. There was high omnivory by Pacific bluefin and yellowfin (high inputs of TG2, TG3, and/or TG4 with no dominance of any individual TG), and high utilization of TG3 by yellowtail: 76%, swordfish: 96%, bonito: 68%, and mako sharks: 85% (Fig 5A and Table 2). Some of these predators showed increased feeding on TG4 (yellowfin tuna: 41%; Pacific bluefin tuna: 17%; bonito: 15%) and some showed an increased level of feeding within TG5 (Pacific bluefin: 9% and yellowtail: 7%) (Fig. 5A and Table 2).

Figure 5. Mixing model estimates of median proportion of diet input from four trophic groups for CCLME predators.

(A) Estimates of proportion of TG2, 3, 4, and 5 in nine predator species. Mean predator δ15N values increase from left to right. Sample size is shown above each column. 95% confidence intervals for input estimates shown in Table 2. (B) Mixing model estimates of prey inputs from TG2, 3, 4, and 5 into tuna diets (albacore ALB, Pacific bluefin PB, and yellowfin tuna YFT) for 2008, 2009, and 2010. ‘nd’ indicates insufficient data for analysis. Sample size is shown above each column.

Inter-annual variability in diet composition was revealed by mixing model results for individual tuna species (yellowfin, Pacific bluefin, and albacore tunas) in 2008, 2009, and 2010 (Fig. 5B). While albacore and bluefin diets were relatively consistent across years, yellowfin showed high use of TG3 in 2008 (63%) and 2010 (85%). In 2009 yellowfin used TG3 to a much lower degree (11%) with higher feeding on TG2 (55%) and TG4 (29%) (Fig. 5B).

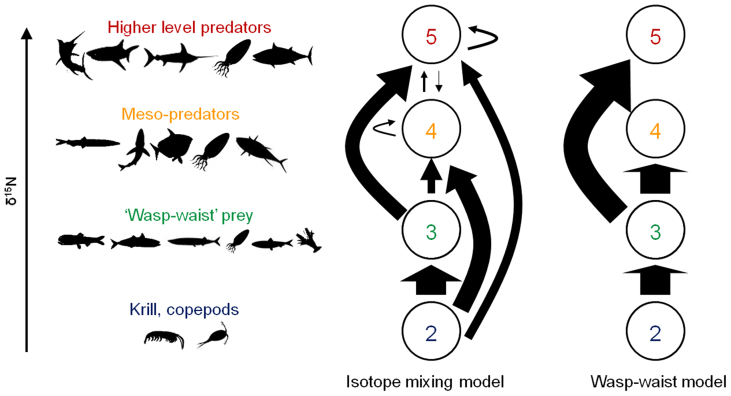

Mixing model results for entire TGs suggest exclusive zooplanktivory by prey species (TG3), zooplanktivory by some predators and high omnivory by other predators, and trophic links across multiple TGs in the southern CCLME (Fig. 6 and Table 2). Results also indicate that TG3 organisms fed entirely on TG2 (99%; Fig. 6 and Table 2). Meso- and higher trophic level predators (TG4 and TG5) fed on all trophic groups, including their own (Fig. 6). Though TG3 prey were the most significant input to TG5 predators (57–69%), they were of less importance to TG4 predators (8–24%) which fed predominately at the zooplankton level (74–84%) (Table 2).

Figure 6. Schematic showing isotope mixing model estimates of food flow through the southern CCLME pelagic ecosystem, indicating high omnivory and high use of TG2 and TG3 by meso- and higher level predators, respectively.

Arrows indicate inputs of a trophic group to another; arrow size is proportional to median mixing model estimates of prey inputs of trophic group to others. 95% confidence intervals for input estimates shown in Table 2. Far right schematic shows proportional prey inputs expected under wasp-waist ecosystem dynamics.

Discussion

SIA data provided insight into the ecosystem dynamics, structure, and effects of predator size on foraging ecology in the southern CCLME, and Bayesian mixing model results allowed the wasp-waist model to be tested in a highly productive eastern boundary current. Our study spanned multiple years and a broad range of species. The use of SIA allowed for a more comprehensive study of trophic structure in a pelagic ecosystem than previous studies, and we provide here long-term, overall trophic dynamics in the southern CCLME over several years.

The relationship between δ13C and δ15N values of southern CCLME organisms was highly linear (Fig. 1), suggesting that these species likely feed within an oceanographic ecosystem with a similar isotopic baseline (i.e. the pelagic food web of the CCLME). This supports life history and electronic tagging data showing high residency within the CCLME5,7,28,29,30,31,32, as high use of other marine regions with different isotopic baselines would likely lead to predator δ13C and δ15N values that deviate from the observed linear pattern. Though some of these species do make seasonal offshore migrations6,7,33,34,35,36, consistency of δ13C and δ15N values with the linear system pattern in isospace indicates high residency within the southern CCLME and the overall importance of the CCLME as a foraging area for these species.

The rapid increase in δ15N with size between 0–25 cm (Fig. 3) suggests this may be a critical size phase in the CCLME, during which trophic level is rapidly increasing. All species in TG2 and TG3 fell within this size range, and in the CCLME organisms less than 25 cm seem most susceptible to predation by upper trophic levels. There was no trend of δ13C and δ15N values with size but high variability in isotope values in organisms between 25 and 250 cm (Fig. 3), the difference between a mackerel- and mako shark-sized predator. Unlike other pelagic ecosystems where organism trophic level (inferred using δ15N values) increased with size37, in the southern CCLME all species greater than ~25 cm appear able to use a diverse prey base leading to variation in predator δ15N values. Comparison of δ13C and δ15N with mean size for multiple predators (Fig. 4) showed no correlation with size for either isotope; this supports studies in coastal systems revealing no effect of body size on δ13C and δ15N values per se38. Different species of similar size had different mean δ13C and δ15N values (e.g. mako and blue sharks, yellowtail and albacore had considerably different δ15N and δ13C values) (Fig. 4). Interestingly, there was intra-specific δ13C and δ15N correlation with size for some species (Supplementary Fig. S2 and Supplementary Table S1). The increase of δ13C and δ15N values in jack mackerel and yellowtail suggests the possibility for ontogenetic increases in trophic level with size for these species, which has been shown in other systems37. Pacific bluefin tuna δ15N values decreased with size; this could be a result of prey switching or habitat use differences across the sampled size range of Pacific bluefin. Overall, these differences are likely linked to species-specific feeding strategies and resultant differences in prey selection; size-based differences in feeding strategies have been observed in other marine systems39.

The two distinct predator groups in isospace (Fig. 2) suggest two feeding strategies: foraging on planktonic organisms by some TG4 species (Pacific mackerel, albacore, and blue sharks) or feeding on TG3 and higher trophic level fish and squids such as pacific and frigate mackerels, barracudinas, and market and jumbo squids by some TG5 predators (Pacific bluefin, mako sharks, yellowfin, swordfish, bonito, and yellowtail). These patterns are supported by mixing model results, which show high zooplanktivory by Pacific mackerel, albacore, and blue shark, omnivory in Pacific bluefin and yellowfin, and high inputs of TG3 to diets of swordfish, yellowtail, bonito, and mako sharks (Fig. 5A). Because all species were sampled in the southern CCLME over the same timeframe, it is unlikely that these differences are a result of differences in prey availability, but rather due to differences in foraging strategies and physiological capabilities. These predators are known to have different thermal physiologies and diving behavior which likely influences their foraging capacity. Pacific bluefin, albacore, yellowfin, swordfish, and mako sharks all have varying degrees of regional endothermy6,7,40,41,42, while the other predator species in this study are ectothermic. Our results support studies that indicate that predator physiology and behavior lead to specialization on particular prey in particular pelagic habitats, such as epipelagic TG3 prey for TG5 predators yellowfin, bonito, and yellowtail27,43,44 and deep scattering layer organisms by TG4 predators blue shark and albacore45,46.

Mixing model results provide new insight on the relative importance of particular prey species. For example, Pacific mackerel, albacore, and juvenile blue sharks are known to feed on plankton (particularly euphausiids) but also on squid and forage fishes26,27,47,48. SIA integrates diet over longer time frames than gut content analysis can often represent, and our results suggest that TG2 species account for more of the diet of TG4 organisms than studies using stomach contents have indicated. These may be important prey in winter months in the CCLME, when TG3 organisms are less available and data for gut content analysis are scarce27,48. TG2 prey may also be digested quickly and thus under-represented in gut content analyses; a recent study showed extensive consumption of salps, another zooplankton resource, by large predators in the Mediterranean pelagic ecosystem using SIA, revealing under-representation of this prey resource using GCA alone49. SIA has the advantage of integrating long-term feeding habits into a single isotopic value for each predator sampled. Many gut content analysis studies rely on opportunistically sampled, line-caught fish, which limits their results to periods when fish are available and actively feeding. These studies are also inherently restricted temporally and spatially. SIA results here likely capture a more comprehensive estimate of predator diets.

Inter-annual comparisons of mixing model results for yellowfin, albacore, and bluefin tunas suggest that trophic dynamics in the CCLME may shift annually, at least for tuna species during the period of this study (Fig. 5B). SIA values reflect previous foraging, and tunas of this size range take over a year to reach steady-state with diet50. Therefore, mixing model results for tuna δ13C and δ15N values for a certain year should roughly reflect feeding habits of the previous year. Mixing model results for yellowfin in 2009 (Fig. 5B) suggest potentially higher TG4 inputs (e.g., squid), and indeed squid dominated the diets of CCLME tuna in 200851. Yellowfin diet estimates for 2010 (Fig. 5B) reflect higher TG3 inputs, and forage fishes were more prevalent in tuna diets in the CCLME in 200951. Thus our results for tuna mirror feeding patterns observed using gut content analysis, and these inter-annual differences highlight the ability of these predators to change their feeding dynamics in response to changing prey conditions. The magnitude of inter-annual differences between the tuna species may also indicate differences in plasticity of the foraging strategies of these predators in the face of varying prey availability. Bluefin and albacore, both highly endothermic, showed the least inter-annual variation while the less endothermic yellowfin varied greatly between 2008, 2009, and 2010. It is possible that yellowfin, being more restricted both latitudinally and vertically within the CCLME due to their narrower thermal niche5, are forced to alter their foraging in response to changes in epipelagic prey availability. Pacific bluefin and albacore tunas would be more capable of pursuing specific prey (e.g., sardine or deep scattering layer organisms) into colder or deeper waters due to their endothermic specialization.

Isotope mixing models also provided estimates of trophic flow between entire trophic groups for the southern CCLME. Our results showed that omnivory increased with trophic level, with the highest trophic group (TG5) feeding on all other TGs including species within TG5. TG3 organisms dominated the diet input estimates of TG5 predators (63%), and predominant feeding on schooling fishes is supported by dietary studies in the CCLME27. The relatively high inputs of TG5 in bluefin, yellowtail, and mako sharks diets (9%, 7%, and 4%) are most likely a result of feeding on TG5 squid (market and jumbo squids) with high δ15N values; feeding studies have shown high consumption of market squid by bluefin and yellowtail on certain occasions and all species have been reported to feed on jumbo squid to various extents26,27,44. Meso-predators in the TG4 group, some of which are often considered large, apex predators (e.g., opah, blue sharks, and albacore) fed largely on TG2 (79%). This suggests a surprising level of zooplanktivory by TG4 as a whole. It suggests that rather than relying on TG3 organisms to transfer energy from the zooplankton level, these large predators are able to directly utilize this often abundant resource. TG3 were of less importance to TG4 (16%) and TG4 and TG5 even less so (< 3%, Table 2).

SIA results of a pelagic ecosystem under wasp-waist control would meet three basic criteria, based on general characteristics of WW systems13,14. First, the prey base would be dominated by one or a few planktivorous organisms or LTLs (here, TG3). Second, most or all predators would be expected to group together isotopically, as they would all feed extensively on this homogeneous prey base. Finally, isotopic mixing models would show that individual predators and higher trophic groups as a whole feed mainly on the TG3 level. Our study allowed for evaluation of each of these three criteria.

The prey base in the southern CCLME from 2007–2010 was not dominated by one or a few species; rather, field sampling and sampling of predator stomachs revealed a high diversity of TG3 prey (Table 1). This result differs from previous studies in the CCLME, when certain TG3 prey such as anchovy dominated the diets of teleost predators, including albacore, Pacific bluefin tuna, and bonito27. Thus our results did not meet criterion 1 for WW control over the course of this study. Results also reveal that diverse prey are available if WW species are at lower abundances, leading to higher resilience of the CCLME food web.

Predators did not group together isotopically as they would if all fed predominantly on WW prey; cluster analysis revealed two distinct predator groups (Fig. 1). Furthermore, once corrected for TDF, it became clear that different foraging strategies existed for different predators, even predators within the same TG, which clustered together in isospace (Fig. 2). The high variability in predator δ13C and δ15N values (Fig. 3 inset) suggests feeding on a wide range of prey, in contrast with criterion 2 for WW control.

Finally, the quantitative SIA results of Bayesian mixing models did not reflect expected feeding patterns by individual predators or by trophic groups as a whole. Some predators fed extensively on TG3 (Fig. 5A), but for others, TG3 accounted for a minority of prey inputs. Additionally, while TG3 was important (63%) to the highest trophic group (TG5), it did not comprise the majority of prey inputs for meso- and apex predators as a whole (Fig. 6 and Table 2). The reliance of TG4 on zooplankton prey (79%) and feeding of TG5 on groups other than TG3 (37%) results in a much more complex, inter-connected food web than that expected under WW conditions (Fig. 6). Thus our results contrast with all three expected criteria for SIA results in a WW ecosystem.

Non-WW conditions in the CCLME contrast with other studies of EBC systems, which suggested WW control in the Benguela, Guinea, and Humboldt currents13. This observed difference has several implications. One is that the southern CCLME, and potentially EBC systems in general, cannot be considered WW systems a priori, but rather must be examined over multiple years and different oceanographic conditions to ascertain trophic relationships. The highest trophic levels may heavily exploit WW prey when they are available, but results here suggest the capacity to forage on other organisms depending on readily available prey species.

Non-WW ecosystem structure would increase ecosystem stability, as there is a positive relationship between ecosystem complexity and ecosystem stability18. Adaptive food choice, leading to apex predators feeding on a diverse prey base and species at intermediate trophic levels being fed upon by multiple predator species, also increases food web stability18 and has been shown to maintain ecosystem biodiversity9,52. This suggests that the southern CCLME pelagic ecosystem may maintain stability and biodiversity via the omnivory and diversity of foraging strategies of predators demonstrated here. Taken together these features of the CCLME ecosystem potentially explain the high resilience of its pelagic fish populations in the face of large scale oceanographic shifts such as Pacific Decadal Oscillations (PDOs) or El Niño Southern Oscillations (ENSO). We demonstrate that predators possess flexibility in prey selectivity which may facilitate switching between prey resources or enable exploitation of ‘loopholes’ in prey availability9. However, less energetic resources, or ‘junk food’ in marine ecosystems, may only provide adequate sustenance and subsequent population stability for limited timeframes53. In the southern CCLME, this timeframe may be long enough for energetically rich prey to rebound and sustain teleost predators, as most studies demonstrating population declines in predators due to lack in prey quantity or quality have been on marine mammals or seabirds2,53,54,55. Numerous compensatory mechanisms (e.g., deep-diving) may dampen or eliminate expected direct consequences of prey depletion for teleosts compared to seabirds, leading to their continual success and presence in the southern CCLME. The interaction of predator foraging plasticity and the availability of abundant and diverse prey at different trophic levels in the CCLME may underlie the high residency and consistent predator presence in this pelagic ecosystem.

There are several assumptions implicit to our approach and to SIA in general. Organism isotope values vary over space and time, and we attempted to sample predator species throughout their residency period in the study area. However, as in all SIA studies, we were unlikely to capture all sources of isotopic variability. Electronic tagging has shown that many of these animals move not only north and south within the CCLME, but also offshore in seasonal patterns5. Brief migrations by some species to isotopically different areas may have slightly affected isotopic values, though not enough for values to clearly discern migrants from the system. The possibility that brief migrations may slightly alter the isotope composition of migratory species, and thus affect trophic inferences, must be taken into account when interpreting SIA results.

Mixing models are sensitive to TDF and prey values; thus accurate values of these parameters are important22. We used experimentally derived TDF values from controlled studies on captive Pacific bluefin tuna50 and two large shark species56. We assumed that Pacific bluefin TDF values were appropriate for teleosts and the TDFs from large sharks56 were appropriate for the shark species sampled here. Our TDF values are the most appropriate available values based on the taxonomy and size of the experimental animals and the predators to which they were applied, and are more appropriate than the mean TDF derived from several taxa in Post 2002 (Δδ15N = 3.4 ± 1‰, Δδ13C = 0.4 ± 1.4‰) that has been used in numerous studies. However, ecosystem-wide SIA studies will no doubt benefit from more lab-based studies on species-specific dynamics of isotopic fractionation relative to diet.

Finally, it should be noted that the CCLME contains predator species and size ranges not included in this study. Seabirds and marine mammals make extensive use of the CCLME5, and seabirds in particular have been shown to be dependent upon epipelagic, TG3 forage fish due to diving limitations2. Additionally, larger individuals of certain species, such as mako and blue sharks, are known to feed on higher trophic level prey in the CCLME, including large teleosts and marine mammals26. Inclusion of the full size range of all species may alter TG composition and change proportional inputs to different TGs based on the foraging strategies of these animals. Thus our results can be generalized only to the teleosts and elasmobranch predators of the size ranges included in our analyses.

Overall this study suggests that prey from several trophic groups are important to multiple predators and trophic groups in the southern CCLME. Forage base in the CCLME is constantly shifting due to changes in oceanographic conditions and fishing pressures2,3,16,54. While the CCLME is utilized by predators for its richness of prey5, several oceanographic parameters likely have impacts on prey availability, predator foraging, and thus predator fitness. Oxygen minimum layer depth affects deep scattering layer composition and the ability of predators to forage on organisms at depth57, upwelling and productivity provide bottom-up controls on TG3 prey58, and variations in ocean temperature alter the availability of many of the prey sampled here3,59. In a changing ocean, over short (ENSO events) and long (climate change) timescales, long-term studies using SIA could reveal shifts in predator diets and indicate how and to what extent large, pelagic predators in the CCLME alter their foraging strategies in different ocean conditions. Our results here suggest that predator feeding varies in the southern CCLME, lending stability to this important upwelling pelagic ecosystem.

Methods

Sampling

Sampling took place between 2007 and 2010 in the summer and fall months (June-October) from the long-range San Diego fishing vessel R/V Shogun in the southern region of the CCLME (28°00′N–33°00′N; 116°32′W–119°13′W, Supplementary Fig. S1) or from fish landed by recreational anglers in San Diego, CA. Samples were collected from multiple species and trophic levels. Skeletal white muscle tissue was collected for fish, mantle muscle tissue for cephalopods, and crustaceans were collected whole. Predators were captured using rod and reel and muscle biopsies were taken from the dorsal musculature. Stomachs were removed from some tuna that were sampled for muscle tissue for diet studies using GCA. Intact prey items (recently consumed and not highly digested) found during GCA of tuna stomachs were used for SIA of prey. For these specimens only internal muscle tissue, which was unexposed to digestive enzymes, was collected. Prey samples were also collected using a dip net. Samples were stored immediately at −5°C.

Prior to analysis, samples were kept at −80°C for 24 h and then freeze-dried for 72 h. Samples were homogenized using a Wig-L-Bug (Sigma Aldrich) and analyses of δ13C and δ15N were conducted at the Stanford Stable Isotope Biogeochemistry Laboratory using a Thermo Finnigan Delta-Plus IRMS coupled to a Carlo Erba NA1500 Series 2 elemental analyzer via a Thermo Finnigan Conflo II interface. Replicate reference materials of graphite NIST RM 8541 (USGS 24), acetanilide, and ammonium sulfate NIST RM 8547 (IAEA N1) were analyzed between approximately 10 samples. Shark tissues were thoroughly rinsed in DI water to extract urea. All δ13C values were arithmetically lipid-normalized based on mass C:N ratios using taxon- or species-specific lipid normalization algorithms reported in Logan et al. 200860. Muscle tissue was extracted from pelagic red crabs P. planipes for analysis; carbonate in copepods and krill was removed using 1 M HCl, then analyzed whole and δ13C values arithmetically normalized according to algorithms for whole invertebrates in Logan et al. 200860. Stable isotope ratios are reported as mean ± SD.

Trophic groups

Organisms were placed into four trophic groups (TG2-5; TG1 represents phytoplankton, not sampled in this study) using cluster analysis (Ward's minimum variance method) of mean δ13C and δ15N values for each species. To view overlap of predators and prey in ‘isospace’ (plots of δ13C versus δ15N) we plotted δ13C and δ15N values of TDF-adjusted predators and trophic groups obtained from cluster analysis. Mean δ13C and δ15N values of predators were adjusted to visualize overlap with potential prey by subtracting laboratory-derived TDF values from mean (± SD) values of δ13C and δ15N for each predator. Teleosts were corrected using TDFs of captive Pacific bluefin tuna Thunnus orientalis (Δδ15N = 1.85 ± 0.38, Δδ13C = 1.83 ± 0.33[50]) and sharks were corrected using TDF values for large (>100 cm) sharks Carcharias taurus and Negaprion brevirostris (Δδ15N = 2.29±0.22, Δδ13C = 0.90±0.33)56. This allowed visualization of overlap of predator species and trophic groups with their potential prey in isospace.

Size effects

We performed correlation analysis (Pearson's correlation; α = 0.05) to investigate the relationship between organism size and δ13C and δ15N values. Correlation analysis of mean size vs. mean δ13C and δ15N values were performed across predators and for individual size vs. individual δ13C and δ15N values within particular prey and predator species. All statistical analyses of isotope data were carried out using MatLab (v. 2009a).

Trophic dynamics

We used a Bayesian mixing model (MixSir v. 1.0.4)22 that takes into account isotopic error by using as inputs all predator δ13C and δ15N values and mean (± SD) δ13C and δ15N values of predator TDFs and prey. We first assessed proportional prey inputs from each trophic group (TG) into individual predator diets (e.g., to what extent do yellowfin tuna feed on organisms in TG2, TG3, TG4, and TG5?). Mixing models sometimes provide multiple solutions for diet input estimates (i.e., bimodal probability distributions). Using priors based on known predator diet can help constrain mixing model estimates22. We generated mixing models using uninformed priors, as well as WW priors that gave more weight to TG3 species. Uninformed priors and doubling probability of TG3 (priors = [1 2 1 1]) led to bimodal solutions for a few species and TG5. Thus we assigned priors of [1 3 1 1] to TG2, TG3, TG4, and TG5, respectively. This assigned equal probability of dietary contributions of TG2, TG4, and TG5, and assumes a three-fold higher likelihood of TG3 (wasp-waist species) in predator diets. This prevented bimodal solutions and made estimates of high non-TG3 diet inputs more compelling due to the weight given TG3 inputs via prior assignments. We also tested the possibility of inter-annual variation in trophic dynamics using SIA values from 2008, 2009, and 2010 for yellowfin, albacore, and bluefin tunas, three species with adequate sample size for inter-annual analyses.

To estimate overall trophic flow between entire trophic groups of the southern CCLME we estimated the relative prey inputs of each TG into the TGs themselves (e.g., to what extent does TG5 feed on organisms in TG2, TG3, TG4, and within TG5?). For TG mixing model runs we used a weighted-mean (weighted by sample size) TDF based on the species composition of each TG. We used Pacific bluefin tuna TDF for teleost predators50, shark TDF for sharks56, squid TDF (Δδ15N = 3.3, Δδ13C = 0.0)61 for cephalopods, and a TDF for small pelagic fish (Δδ15N = 1.88, Δδ13C = 1.52)62 for TG3 fish. We used mean δ13C and δ15N ± SD value for each TG as prey inputs for these mixing model runs. We used priors reflecting general wasp-waist assumptions [1 3 1 1] as above and performed 107 iterations for all mixing model runs. Proportional diet inputs are reported to the nearest percent (Table 2). All statistical analyses of isotope data were carried out using MatLab (v. 2009a).

Ethics statement

All studies were carried our in accordance with the guidelines as stated by Stanford University animal use protocols and all studies were approved by APLAC of Stanford University. Samples were collected according to IACUC APLAC Stanford University protocols for fish and other vertebrates. Some tuna samples were collected on specific trips in Mexican waters obtained under permits issued to Stanford University from the Mexican Government to BAB. Samples from other species were collected under an inter-agency agreement between NOAA and California Fish and Game.

Author Contributions

DJM designed the study, performed SIA, and wrote the initial manuscript. BAB, DJM, OES, and HD acquired samples. DJM, SYL, and ABC analyzed the data. All authors contributed to decisions regarding data analysis and figure preparation. All authors commented on and contributed to the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank the crew of the F/V Shogun for assistance in sample collection, especially N. Kagawa and B. Smith. We thank Ted Dunn for providing access to sample collection aboard F/V Shogun. D. Mucciarone and R. Dunbar provided valuable assistance with stable isotope analysis and quality control. We thank B. Popp for valuable comments on the manuscript. A. Norton, L. Rodriguez, R. Schallert, J. Adelson, T. Brandt, E. Estess, and N. Arnoldi assisted in both acquisition and preparation of samples. Samples collected on specific trips in Mexican waters were obtained under permits issued to Stanford University from the Mexican Government to BAB and DJM. Samples from other species were collected under an inter-agency agreement between NOAA and California Fish and Game. We thank the Mexican Government for allowing collection of Pacific bluefin tuna in their waters. The animal care and use program at Stanford University provided APLAC oversight to BAB and DJM for tuna collections.

References

- Sherman K. & Alexander L. Variability and management of large marine ecosystems (Westview Press, Inc, Boulder, CO, 1986). [Google Scholar]

- Cury P. M. et al. Global seabird response to forage fish depletion - one-third for the birds. Science 334, 1703–1706 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez F. P., Ryan J., Lluch-Cota S. E. & Niquen C M. From anchovies to sardines and back: multidecadal change in the Pacific Ocean. Science 299, 217–221 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PICES. in PICES Special Publication (North Pacific Marine Science Organization., 2004).

- Block B. A. et al. Tracking apex marine predator movements in a dynamic ocean. Nature 475, 86–90 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boustany A. M., Matteson R., Castleton M., Farwell C. & Block B. A. Movements of Pacific bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis) in the Eastern North Pacific revealed with archival tags. Prog. Oceanogr. 86, 94–104 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer K., Fuller D. & Block B. Movements, behavior, and habitat utilization of yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) in the northeastern Pacific Ocean, ascertained through archival tag data. Mar. Biol. 152, 503–525 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Pauly D., Christensen V., Dalsgaard J., Froese R. & Torres F. Fishing down marine food webs. Science 279, 860–863 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakun A. & Broad K. Environmental ‘loopholes’ and fish population dynamics: comparative pattern recognition with focus on El Niño effects in the Pacific. Fish. Oceanogr. 12, 458–473 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Cury P., Shannon L. & Shin Y.-J. in Responsible fisheries in the marine ecosystem. (eds. Sinclair M., & Valdimarsson G.) 103–123 (FAO, Rome, & CABI Publishing, Wallingford, UK, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- Baum J. K. & Worm B. Cascading top-down effects of changing oceanic predator abundances. J. Anim. Ecol. 78, 699–714 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur R. D. & Pearcy W. G. Effects of environmental variability on trophic interactions and food web structure in a pelagic upwelling ecosystem. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 84, 101–119 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Cury P. et al. Small pelagics in upwelling systems: patterns of interaction and structural changes in “wasp-waist” ecosystems. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 57, 603–618 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Rice J. in Climate Change and Northern Fish Populations (ed. Beamish R. J.) 516-568 (Canadian Special Publication of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- Bakun A. 323 (University of California Sea Grant, San Diego, California, USA, in cooperation with Centro de Investigaciones Biologicas de Noroeste, La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 1996).

- Shannon L. J., Cury P. M. & Jarre A. Modelling effects of fishing in the Southern Benguela ecosystem. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 720–722 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Miller T. W., Brodeur R. D., Rau G. & Omori K. Prey dominance shapes trophic structure of the northern California Current pelagic food web: evidence from stable isotopes and diet analysis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 420, 15–26 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Gross T., Rudolf L., Levin S. A. & Dieckmann U. Generalized models reveal stabilizing factors in food webs. Science 325, 747–750 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyslop E. J. Stomach contents analysis-a review of methods and their application. J. Fish Biol. 17, 411–429 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Fry B. Stable Isotope Ecology (Springer-Verlag, New York, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Post D. M. Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology 83, 703–718 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Moore J. W. & Semmens B. X. Incorporating uncertainty and prior information into stable isotope mixing models. Ecol. Lett. 11, 470–480 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips D. L. & Gregg J. W. Source partitioning using stable isotopes: coping with too many sources. Oecologia 136, 261–269 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnell A. C., Inger R., Bearhop S. & Jackson A. L. Source partitioning using stable isotopes: coping with too much variation. PloS ONE 5, e9672 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field J. C. & Francis R. C. Considering ecosystem-based fisheries management in the CaliforniaCurrent. Mar. Pol. 30, 552–569 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Preti A. et al. Comparative feeding ecology of shortfin mako, blue and thresher sharks in the California Current. Environ. Biol. Fish. 1–20 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Pinkas L., Oliphant M. S. & Iverson I. L. K. Food habits of albacore, bluefin tuna, and bonito in California waters. Fish. Bull. 152, 1–105 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. A. & MacCall A. D. California's Pacific bonito resource, its status and management. Calif. Fish. Game Mar. Res. Tech. Rep. 35 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Bedford D. W. in California Sea Grant Publication UCSGEP-92-12 (eds. Leet S., , Dewees C. M., & Haugen C. W.) 49–51 (Davis, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- Cartamil D. et al. Diel movement patterns and habitat preferences of the common thresher shark (Alopias vulpinus) in the Southern California Bight. Mar. Freshw. Res. 61, 596–604 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. A. The status of the California yellowtail resource and its management. Calif. Fish. Game Mar. Res. Tech. Rep. (1973). [Google Scholar]

- Holts D. B. in California's living marine resources and their utilization (eds. Leet S., , Dewees C. M., & Haugen C. W.) 53–54 (Davis, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- Childers J., Snyder S. & Kohin S. Migration and behavior of juvenile North Pacific albacore (Thunnus alalunga). Fish. Oceanogr. 20, 157–173 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer K. M., Fuller D. W. & Block B. A. Movements, behavior, and habitat utilization of yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) in the Pacific Ocean off Baja California, Mexico, determined from archival tag data analyses, including unscented Kalman filtering. Fish. Res. (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Hinton M. G., Bayliff W. H. & Suter J. M. in Stock Assessment Report 291–336 (Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- Squire J. Striped marlin, Tetrapturus audax, migration patterns and rates in the northeast Pacific Ocean as determined by a cooperative tagging program: its relation to resource management. Mar. Fish. Rev. 49, 26–43 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Revill A., Young J. & Lansdell M. Stable isotopic evidence for trophic groupings and bio-regionalization of predators and their prey in oceanic waters off eastern Australia. Mar. Biol. 156, 1241–1253 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Vinagre C., Máguas C., Cabral H. N. & Costa M. J. Effect of body size and body mass on δ13C and δ15N in coastal fishes and cephalopods. Estuar. Coast. Shelf S. 95, 264–267 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Scharf F. S., Juanes F. & Rountree R. A. Predator size-prey size relationships of marine fish predators: interspecific variation and effects of ontogeny and body size on trophic-niche breadth. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 208, 229–248 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Carey F. G., Teal J. M., Kanwisher J. W., Lawson K. D. & Beckett J. S. Warm-Bodied Fish. Integr. Comp. Biol. 11, 137–143 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- Block B. A. et al. Migratory movements, depth preferences, and thermal biology of Atlantic bluefin tuna. Science 293, 1310–1314 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcinek D. J. et al. Depth and muscle temperature of Pacific bluefin tuna examined with acoustic and pop-up satellite archival tags. Mar. Biol. 138, 869–885 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Potier M. et al. Feeding partitioning among tuna taken in surface and mid-water layers: the case of yellowfin (Thunnus albacares) and bigeye (T. obesus) in the western tropical Indian Ocean. .W. Ind. Ocean J. Mar. Sci. 3, 51–62 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Baxter J. L. A study of the yellowtail, Seriola dorsalis (Gill). Calif. Fish Game Fish Bull. 110 (1960). [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand et al. Tuna food habits related to the micronekton distribution in French Polynesia. Mar. Biol. 140, 1023–1037 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Carey F. G., Scharold J. V. & Kalmijn A. J. Movements of blue sharks (Prionace glauca) in depth and course. Mar. Biol. 106, 329–342 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Fitch J. E. Pacific mackerel. Cal. Coop. Ocean. Fish. 29–32 (1956). [Google Scholar]

- Glaser S. Interdecadal variability in predator-prey interactions of juvenile North Pacific albacore in the California Current System. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 414, 209–221 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Cardona L., Álvarez de Quevedo I., Borrell A. & Aguilar A. Massive consumption of gelatinous plankton by Mediterranean apex predators. PLoS ONE 7, e31329 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan D. J. et al. Tissue turnover rates and isotopic trophic discrimination factors in the endothermic teleost, Pacific bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis). PLoS ONE (submitted). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass O., Dewar H., Wells R. J. D. & Kohin S. Foraging ecology of tunas in the Southern California Bight. (in prep).

- Kondoh M. Foraging adaptation and the relationship between food-web complexity and stability. Science 299, 1388–1391 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Österblom H., Olsson O., Blenckner T. & Furness R. W. Junk-food in marine ecosystems. Oikos 117, 967–977 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. D. M. et al. Impacts of fishing low-trophic level species on marine ecosystems. Science 333, 1147–1150 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakun A., Babcock E. A. & Santora C. Regulating a complex adaptive system via its wasp-waist: grappling with ecosystem-based management of the New England herring fishery. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 66, 1768–1775 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Hussey N. E., Brush J., McCarthy I. D. & Fisk A. T. δ15N and δ13C diet-tissue discrimination factors for large sharks under semi-controlled conditions. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 155, 445–453 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince E. D. & Goodyear C. P. Hypoxia-based habitat compression of tropical pelagic fishes. Fish. Oceanogr. 15, 451–464 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Ware D. M. & Thomson R. E. Bottom-up ecosystem trophic dynamics determine fish production in the Northeast Pacific. Science 308, 1280–1284 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R. C., Hare S. R., Hollowed A. B. & Wooster W. S. Effects of interdecadal climate variability on the oceanic ecosystems of the NE Pacific. Fish. Oceanogr. 7, 1–21 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Logan J. M. et al. Lipid corrections in carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analyses: comparison of chemical extraction and modelling methods. J. Anim. Ecol. 77, 838–846 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson K. A. & Cherel Y. Isotopic reconstruction of marine food webs using cephalopod beaks: new insight from captively raised Sepia officinalis. Can. J. Zool. 84, 766–770 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Pepin P. & Dower J. F. Variability in the trophic position of larval fish in a coastal pelagic ecosystem based on stable isotope analysis. J. Plankton Res. 29, 727–737 (2007). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information