Abstract

The overexpression of arachidonyl lipoxygenase-12 (ALOX12) in breast cancer has been reported. Hence, we examined whether a non-synonymous polymorphism of ALOX12 (mRNA, A835G; Gln261Arg) is associated with breast cancer in females. The polymorphism was detected in genomic DNA by PCR-RFLP. The association between the A835G polymorphism and breast cancer risk was measured by odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using Fisher's exact test, and differences were considered significant at p<0.05. The frequencies of AA (wild-type), GG (homozygous variant) and AG (heterozygous variant) were 59.5, 0.9 and 39.6% in the controls, and 39.3, 2.5 and 58.2% in the breast cancer cases, respectively. The frequency of the AG genotype was higher in the patients compared to the controls (p<0.0014). The frequency of the GG variant was 2.5 and 0.9% in the cancer subjects and controls, respectively. The relative risk of breast cancer was 2 times greater (OR=2.227) at 95% CI when compared to the relative risk of the heterozygous variant. For the GG genotype, the risk was 4 times greater (OR=4.125) at 95% CI than that of the controls, suggesting a positive association of the AG genotype with the occurrence of breast cancer. The frequencies of the polymorphism were different in different populations. The Arg/Gln and Arg/Arg variants were associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, and the frequencies of the variants differed considerably among various populations. The identification of a gene with links to breast cancer may impact screening, diagnosis and drug development.

Keywords: 12-lipoxygenase, arachidonyl lipoxygenase-12, breast cancer, lipoxygenase, single-nucleotide polymorphism, 2-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid, polymorphism and gene variants

Introduction

Arachidonic acid metabolites regulate a variety of biological processes (1,2), which play a key role both in normal development and in various pathologies, including cancer (3–7). Arachidonic acid, a C20 tetraunsaturated fatty acid (20:4, ω-6) is present in cell membranes esterified to glycerolipids at the sn-2 position (8) and is released from lipids by catalytic action of cytosolic phospholipase-A2 (cPLA2) in response to various stimuli (9). The arachidonic acid in its free form is mainly metabolized by cyclooxygenases (COXs) and arachidonyl lipoxygenases (ALOXs) (2,8,10,11) and to a small extent by cytochrome P450 enzyme (12). The metabolism of arachidonic acid by the COX or ALOX pathways generates eicosanoids (thromboxanes, leukotrienes, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids and lipoxins), which are implicated in cancer (13). Aberrations in the arachidonic acid metabolism via the COX and LOX pathways are shown to be associated with cancer development, both in animals and humans (7).

Interest in the ALOX pathway and its metabolites is increasing, although the major focus of cancer researchers has been on the COX pathway. ALOXs are a family of nonheme iron dioxygenases which differ in their regio-specificity. LOXs are named based on the position at which they incorporate oxygen into arachidonic acid. Four LOXs, ALOX5, 8, 12 and 15, are present in humans (10,14–16). ALOX12 metabolizes arachidonic acid primarily into 12S-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12S-HpETE), which is further reduced by glutathione peroxide to 12S-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12S-HETE) (10).

ALOX12-derived bioactive substances, such as 12S-HETE, hepoxilins and lipoxins, play a key role in cell signaling, cell structure, cell adhesion, ROS production and inflammation (14,17,18). Hence, any imbalance in eicosanoids may lead to abnormal generation of ROS, inflammation and the development of cancer (19–22). Several lines of evidence have implicated ALOXs and their products in various pathologies linked with inflammation, including Alzheimer's disease (23,24), atherosclerosis (25,26), hypertension (27), stroke (27–29) and cancer (7). Evidence links up-regulated ALOX12 expression to the development of cancer, sustenance, growth and metastasis (11,30–34). Overexpression of ALOX12 has been demonstrated in various types of cancers, including breast, renal, pancreatic and prostate (13,35–37). Products of the ALOX5 and 12 pathways, 5S-HETE and 12S-HETE, promote proliferation, cell motility and invasion, respectively, in cancer cells (38,39).

All human LOX genes, apart from ALOX5, are clustered on the short arm of chromosome 17 within a few megabases of each other. The gene encoding ALOX12 is located on chromosome 17p13.1, while ALOX15, which has 86% sequence similarity to ALOX12, is present on chromosome 17p13.2. The genes encoding ALOXs are polymorphic. Polymorphisms in ALOX12 may affect the expression of ALOX12 or alter the stability or activity of the enzyme. Among the polymorphisms of ALOX12 in humans, a non-synonymous polymorphism in exon 6 (mRNA, A835G) results in an amino acid change from glutamine to arginine at position 261 (Gln261Arg) of the enzyme. This polymorphism is functional as it affects ALOX12 enzyme activity (40). Since altered enzyme activity is likely to cause aberrations in arachidonic acid metabolism, identifying the frequency of the ALOX12 genomic polymorphism and exploring its association with breast cancer is of clinical importance. To our knowledge, no reports exist involving the association of the non-synonymous polymorphism (mRNA, A835G; protein, Gln261Arg) with breast cancer. In addition, studies regarding the association of the polymorphism with colorectal cancer risk are ambiguous. In addition to the lack of information regarding the association of the polymorphism with breast cancer, the frequency of the genotype in various populations, including the Indian population, remain unknown. Therefore, in the present study we examined the frequency of the polymorphism in normal subjects and explored the association of the polymorphism with female breast cancer.

Materials and methods

Study design

The study was designed to identify the frequency of the polymorphism (mRNA, A835G; protein, Gln261Arg) in the coding region in normal subjects and to ascertain whether the polymorphism is associated with the occurrence of cancer. All study subjects were of Indian origin (from Andhra Pradesh, one of the four southern states of India) and unrelated. The study was approved by the institute's ethics committee.

Genotyping

The blood samples from the cases were collected from patients visiting our institute, whereas the blood samples from the controls (apparently healthy individuals) were collected from various sources within Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India. Peripheral blood samples were collected into sterile EDTA-coated vacutainer plastic tubes (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) from consenting participants. Genomic DNA was extracted from the blood and isolated using a salting-out protocol (41) with few modifications. Isolated DNA was stored in Tris-EDTA buffer, pH 8.0. The genomic polymorphism was identified by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) technique.

Polymerase chain reaction

The ALOX12 gene region encompassing the polymorphism (Arg261Gln) was amplified specifically using the following primers: forward primer, 5′-CCA GTG GGG CAG GAT GAT GAG TTG-3′ and reverse primer: 5′-GGA GAG AAC AGT GCC AGG CAG-3′. The primers were synthesized at a commercial facility in Hyderabad (Bioserve, Hyderabad, India). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions for the specific amplification of the gene region were optimized for annealing temperature, MgCl2 and primer concentrations. The expected amplicon size was 187 bp. PCR was carried out using a PCR kit (Bioserve) in a total volume of 50 μl. The PCR mixture contained 2.5 μl of 25 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dNTP mixture, 160 pmol of each primer (forward and reverse primers), 0.2 μl of Taq (5 U/μl) and a DNA template. The reaction volume was made up to 50 μl with sterile water. The PCR reaction was carried out in a IQ5 thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using the following optimal conditions. Initial denaturation was carried out at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 35 sec, annealing at 56°C for 35 sec and extension at 72°C for 40 sec. After completion of 35 cycles, a final extension step was carried out at 72°C for 5 min. The optimized PCR conditions given were used throughout the study. PCR amplicon size was identified by electrophoresis using 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide under standard electrophoretic conditions. The bands were visualized under UV light, and the gel was imaged using the Gel Dock System (Bio-Imaging System, Hyderabad, India).

Restriction fragment length polymorphism

The PCR amplicon was subjected to digestion by Eco24I (BanII) restriction enzyme (Eco24I restriction enzyme kit; Fermentas, Canada). Digestion with the restriction enzyme was carried out for a maximum of 16 h at 37°C using 5 units of Eco24I restriction enzyme and 10 μl of PCR product with 10X buffer tango. The specific restriction site for the Eco24I enzyme is:

After incubation, the restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) products were separated on 3% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide using standard electrophoretic conditions. The bands were visualized as previously described. The G allele has an Eco24I restriction site. Expected RFLP fragment sizes were: AA genotype (wild-type), 187 bp; AG heterozygous variant, 187 bp; and GG homozygous variant, 121 and 66 bp. Samples of breast cancer and controls were randomly tested by an objective individual within the facility. The polymorphisms in ALOX12 were validated by sequencing four representative samples (the PCR amplicons). The samples were sequenced at a commercial facility (Vimta, Hyderabad, India).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.2 software. An association between the A835G polymorphism and breast cancer risk was measured by the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), using Fisher's exact test (two-tailed). Differences between cancer and control groups were considered statistically significant at p<0.05. The breast cancer samples were from females and hence the breast cancer data were compared to female control samples.

Results

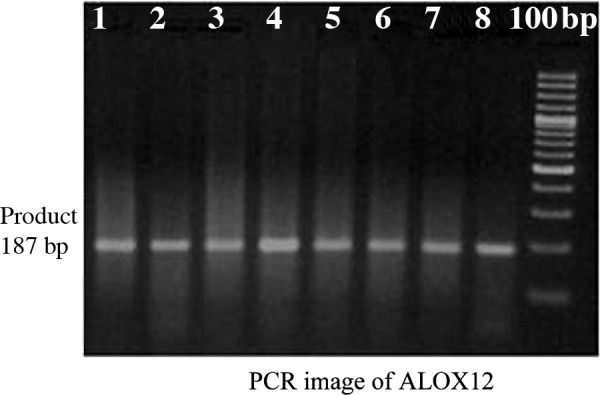

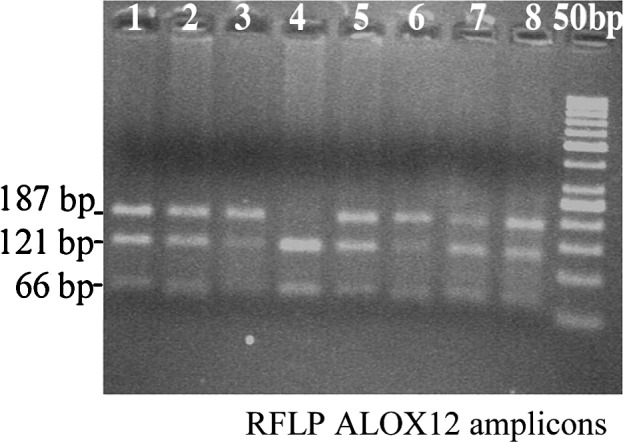

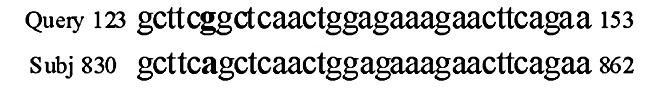

As shown in Fig. 1, PCR yielded an amplicon of the expected size, 187 bp. BanII digestion products were also of the expected sizes (Fig. 2). Polymorphisms determined by PCR-RFLP and electrophoresis were validated by sequencing random samples (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

Lanes 1–8 are PCR products of the ALOX12 gene obtained from breast cancer patients. The unnumbered lane (adjacent to lane number 8) is the 100-bp DNA ladder. PCR yielded an amplicon of the expected size (187 bp) and was devoid of any non-specific amplification.

Figure 2.

Lanes 1–3, 5, 7 and 8 are of AG genotype, lane 4 is of GG genotype and lane 6 is of AA genotype. The unnumbered lane (adjacent to lane 8) is the 50-bp DNA ladder.

Figure 3.

Validation of the ALOX12 polymorphism (A835G; Arg261Gln) by sequencing. The sample sequence was compared to Homo sapiens arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase mRNA (ALOX12; Ref., NM 000697.2; gene ID, 239 ALOX12), using BLAST, NCBI, USA.

Frequencies of the ALOX12 polymorphism, A835G (mRNA), were compared between females with and without breast cancer (controls) and the data are presented in Table I. The frequencies of AA (wild-type), GG (homozygous variant) and AG (heterozygous variant) were found to be 59.5, 0.9 and 39.6% in the controls, respectively. In contrast, the frequencies were found to be 39.3, 2.5 and 58.2% for AA, GG and AG genotypes, respectively, in the breast cancer cases. When the frequencies were compared between the breast cancer and control subjects, the frequency of the AG genotype was higher in the breast cancer patients. The difference between the breast cancer and control subjects was statistically significant (p<0.0014). The frequency of the GG variant was 2.5% in the female breast cancer cases and 0.9% in the controls. The GG frequency in the breast cancer patients was ∼3 times that in the controls. However, the difference was not statistically significant, which may have been due to the sample size. In addition, the frequency of the variants (AG + AA) in the breast cancer patients remained statistically significant when compared to the controls (p<0.0001). The results presented in Table I demonstrate a positive association of the genotype AG with the occurrence of breast cancer, and the relative risk of breast cancer was slightly more than 2 times (OR=2.227) at 95% CI as compared to the controls. Regarding the GG genotype, the risk was 4 times (OR=4.125) at 95% CI when compared to the controls. Female subjects with ≥1 Arg at 261 position in the ALOX12 protein had an ∼378% increased risk of breast cancer when compared to subjects with two copies of the Gln/Gln genotype.

Table I.

Association of the ALOX12 polymorphism with breast cancer in females.

| Genotype | Breast cancer (n=163; 59.5%)

|

Controls (n=111; 40.5%)

|

p-valuea | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Wild-type (A/A) | 64 | 39.3 | 66 | 59.5 | 1.0 | |

| HetVar (A/G) | 95 | 58.2 | 44 | 39.6 | 0.0014a | 2.227 (1.356 and 3.656) |

| HomoVar (G/G) | 4 | 2.5 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.1769 | 4.125 (0.449 and 37.909) |

| Var (A/G+G/G) | 99 | 60.7 | 45 | 40.5 | 0.0001a | 3.781 (2.368 and 6.039) |

Statistical comparisons were carried out between the normal and breast cancer subjects (total, n=274) with respect to wild-type and heterozygous (HetVar), wild-type and homozygous (HomoVar) and wild-type and variants (Var). Differences between values were considered significant only at p<0.05.

As shown in Table II, the frequencies of the variants identified in the Indian population (present study) were compared to the frequencies reported in Caucasians (42,43), Blacks (42), Chinese (40), Koreans (44), Brazilians (45) and Spanish (27). The frequencies appeared to vary in the various populations. In Indians, the AA (261Gln) variant was the most predominant amounting to nearly 60%, and the AA was the least predominant being present only in 1% of the control females. The heterozygous variant AG was present in 39% of the subjects. On the other hand, the AA (261Gln) variant was present in only 17% of the Caucasians (43), 19% of the Spanish (27) 22.5% of the Brazilians (45) and 23.7% of the Chinese (40). Nevertheless, the GG frequency was the highest in the Brazilian population, accounting for 40% (45).

Table II.

Variations in the frequencies of the ALOX12 polymorphism (A835G; Gln261Arg) in different populations.

| Variant | India | USA | USA | USA | Brazil | China | Korea | Spain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gln/Gln (AA) | 59.5 | 17.0 | 37.0 | 40.9 | 22.5 | 23.7 | 31.4 | 19 |

| Gln/Arg (AG) | 39.6 | 49.3 | 50.5 | 45.5 | 37.5 | 51.0 | 49.4 | 47 |

| Arg/Arg (GG) | 0.9 | 33.7 | 13.5 | 13.6 | 40.0 | 25.3 | 19.3 | 34 |

| Gln/Arg (AG) + Arg/Arg (GG) | 40.5 | 83.0 | 64.0 | 59.1 | 77.5 | 76.3 | 68.7 | 81 |

| Population/gender | Indian/female (100%) | Predominantly Caucasians (88%)/female (41%) | Caucasians/female (52%) | Blacks (52%) | Brazilian/female (69%) | Chinese/female (37.2%) | Koreans/female (62.0%) | Spanish/male (100%) |

| Reference | Present study | (43) | (42) | (42) | (45) | (40) | (44) | (27) |

Discussion

The data presented in this report suggest the association of the ALOX12 polymorphism (Gln261Arg) with breast cancer. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to link the ALOX12 polymorphism with breast cancer in females. Our data also revealed wide variations in the frequencies of the ALOX12 variants (Gln/Gln, Gln/Arg and Arg/Arg) in various populations.

Cancer is a major cause of mortality globally. Worldwide, cancer is expected to account for 18% of all mortalities by the year 2030 (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/index.html). However, 30% of these are preventable (46). Breast cancer is the most common cancer of women in Western countries, such as the US, France, Germany and the UK (47). In contrast, rates of breast cancer incidence are reported to be low in developing countries, yet the mortality rates are higher when compared to advanced countries with higher incidence rates of breast cancer (48). In addition to the problem of higher mortality rates, breast cancer incidence rates are rapidly increasing in developing countries, such as India, particularly in urban areas (48). The increasing incidence of breast cancer across the globe warrants the development of an early detection system to identify populations that are predisposed to developing breast cancer. Identifying individuals harboring gene variants linked to cancer is a crucial step in the prevention and development of specific and effective treatment strategies. Genetic factors have been implicated in breast cancer development and its sustenance. Early detection has reduced mortality rates in breast cancer cases in the US and affluent European countries even in the face of the increasing rates of breast cancer incidence. Since nearly one-third of cancer deaths are preventable, it is prudent to identify genetic markers which may aid in early detection. Moreover, further knowledge concerning genetic variants and their phenotypes is the key to understanding individual susceptibility to cancer and the reason why individuals respond differently to a given anti-cancer treatment.

Genetic factors confer susceptibility to disease, impact disease progression or increase resistance to disease. Cancers are not caused by one genetic defect, but result from a complex interplay among a number of genes, apart from the contribution from epigenetic factors. Although a number of breast cancer-associated genes, including Her2/neu, BRCA1 and 2, Top2A, cMYC and p53, have been identified and are used in a clinical setting, many have yet to be identified, which would contribute towards elucidating the complexities of cancer and further promoting the struggle against breast cancer. The Her2/neu oncogene overexpression is present in only 1/4 of breast cancer tumors (49,50). Similarly, BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations account for approximately 30% of all hereditary breast cancer cases (51), and the mutations occur in only 5–10% of total breast cancer cases among Caucasian women in the US (51). It is unclear why these mutations are found only in a subset of cancer patients. Such selective association of these genes with breast cancer underscores the need for exploring other candidate genes with links to the disease.

The examination of individual candidate genes for identifying populations at a high risk of developing breast cancer and other gene-linked diseases remains effective, as it provides specific and focused information even with the advent of genome-wide scan technology. Genome scans and microarrays, despite their capabilities and success, may overlook key disease susceptibility alleles due to no or poor coverage of certain gene regions and false-positives and -negatives. Identifying genetic variations which increase the risk of cancer is likely to shed light on molecular mechanisms that underlie cancer development, sustenance, growth and metastasis. Such understanding of the disease process will not only aid in the early detection of populations predisposed to cancer, but also in developing more potent anti-cancer drugs with fewer side effects.

Inflammatory pathways, particularly COX-1 and COX-2 and to a lesser extent ALOXs, have attacted the attention of cancer researchers due to the reported anti-cancer effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin, ibuprofen and sulindac (52). Involvement of the LOX pathway in cancer, including breast cancer, has been reported, and studies have unequivocally shown a link between the LOX pathway and cancer. Up-regulated expression of LOXs has been determined in both animal models of cancer (32) and in humans (7,30). Jiang et al (36) and Mohammad et al (37) showed increased levels of ALOX12 in breast cancer. However, studies on the ALOX12 polymorphism in relation to human diseases are limited. Two copies of 261Gln in ALOX12 were shown to increase the risk of albuminuria (53). One recent publication also reported the association of ALOX12 with the onset of natural menopause in Caucasian females (54), indicating a role for ALOX12 in hormone-related events in females.

The ALOX12 polymorphism has been shown to be associated with diseases, including hypertension, diabetic nephropathy and colorectal cancer (27). However, little information exists on the association of the ALOX12 polymorphism with other types of cancers. Even the available reports on ALOX12 and colon/colorectal cancer are conflicting. Goodman et al (42) reported that the ALOX12 polymorphism is not linked to colon cancer risk in Caucasians and African-American population, whereas Tan et al (40) showed a positive association between the ALOX12 polymorphism and colon cancer. Guo et al (55) showed that ALOX12 (Gln/Gln) is linked to an increased risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (55). On the other hand, an inverse relation between colon cancer and the ALOX12 polymorphism was reported by Gong et al (43). To the best of our knowledge, the association between the ALOX12 polymorphism and breast cancer remains unexplored. The polymorphism is of importance as the substitution of glutamine with arginine at position 261 resulting from the single-nucleoptide polymorphism is in a conserved region of the LOX (45).

In this study, we observed that the frequency of the AG heterozygous variant (AG) was higher in female breast cancer patients compared to control females. The difference amounted to approximately 19%, which was statistically significant. The data presented also suggests that variants, AG and GG, are associated with increased risk of breast cancer based on the OR value of 2.227 (95% CI, 1.356–3.656). The combined OR for both homozygous and heterozygous variants (GG + AG) was also suggestive of the increased risk of breast cancer with the polymorphic variants. As the polymorphism alters the amino acid from glutamine to arginine, it is likely to alter the enzyme kinetics which may affect the levels of the ALOX12 metabolites (40,56,57). Hypertensive patients with GG homozygous variants were found to have higher amounts of urinary 12-HETE when compared to patients with either the AA or AG variant (27). As 12-HETE and other metabolites are implicated in various processes, including cell proliferation, adhesion and invasiveness of cancer cells (1,58–62), anomalies in the generation of these metabolites are likely to play a role in the development of cancer, its growth and metastasis. However, a recent study reported that 12-HETE reduces cell viability in human islets and insulin secretion (63). Notably, the chromosome 17, which is home for the ALOX12 gene, also houses genes encoding p53, cMYC, Her2/neu, BRCA1 and TOP2A, which are linked to breast cancer. In addition, another member of the LOXs is also present in close vicinity to the ALOX12 gene.

In addition to the association of the polymorphism with the increased risk of breast cancer, we also observed that the frequencies of the variants are different in the Indian population when compared to Caucasian and Chinese populations. A comparison of our data to other published reports revealed wide variations in the frequencies at which the variants are present in different populations (Table II). In the Indian population, Gln/Gln is the most widely present variant and the Arg/Arg variant is the least prevalent, accounting for only 0.9% of the subjects. The heterozygous variant, Gln/Arg, is the most predominant variant in Caucasian, Black, Chinese, Korean and Spanish populations (Table II). Slightly more than 50% of the Han Chinese population were reported to contain the heterozygous variant (40). In the Indian population, homozygous Gln/Gln is the major variant. In contrast, the majority of Brazilians have the Arg/Arg variant as opposed to the Indian population, where the frequency is only 0.9% (45). The differences in data may be attributed to the varying origins of the populations. Notably, the frequencies of the variants were similar in Caucasians and Blacks living in the US (42). The polymorphic changes identified may be of significance as the change occurs at a conserved region of the ALOX (45).

The most effective ways to reduce the incidence and mortality rates of breast cancer are early detection, effective anti-cancer treatment strategies and prevention. Screening apparently healthy populations for the ALOX polymorphism along with other known breast cancer-associated gene variants may identify populations who are at high risk for developing breast cancer and may aid in early detection.

To fully understand the functional impact of gene variants in both normal and breast cancer subjects, it is crucial to determine the enzyme kinetic properties of the ALOX12 variants and assess their impact on the formation of various products of the ALOX12 pathway. In conclusion, our data indicate that GA and GG variants resulting in Arg/Gln and Arg/Arg at the 261-amino acid position of the ALOX12 protein may confer susceptibility to breast cancer in females, at least in the Indian population. Our study also reveals that the frequencies of polymorphic variants differ considerably among Caucasian, Black, Chinese, Korean, Brazilian and Spanish populations. It should be noted that our study included only females, while previous studies, with the exception of a study from Brazil (males only), included both males and females.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our appreciation for the help from the surgical oncologists, medical oncologists and radiation oncologists. We would also like to acknowledge the help of Mr. Udaya Kumar with the statistics, as well as the valuable assistance of Ms. W. Harpreet and Mrs. T. Vidya.

Abbreviations:

- ALOX12

arachidonyl lipoxygenase-12

- COX-1

cyclooxygenase-1

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- LOX

lipoxygenase

- 12-HETE

12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- 12-HpETE

12-hydro-peroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RFLP

restriction fragment length polymorphism

References

- 1.Honn KV, Tang DG, Gao X, Butovich IA, Liu B, Timar J, Hagmann W. 12-Lipoxygenases and 12(S)-HETE: role in cancer metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Res. 2003;13:365–396. doi: 10.1007/BF00666105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang DG, Chen YQ, Honn KV. Arachidonate lipoxygenases as essential regulators of cell survival and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5241–5246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connolly JM, Rose DP. Enhanced angiogenesis and growth of 12-lipoxygenase gene-transfected MCF-7 human breast cancer cells in athymic nude mice. Cancer Lett. 1998;132:107–112. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamitani H, Ikwa H, Hsi LC, Wantanabe T, Dubois RN, Eling TE. The possible involvement of 15-lipoxygenase/leukocyte type 12-lipoxygenase in colorectal carcinogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;469:593–598. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4793-8_86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steele VE, Holmes CA, Hawk ET, Kopelovich L, Lubet RA, Crowell JA, Sigman C, Kelloff GJ. Lipoxygenase inhibitors as potential cancer chemopreventives. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:467–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jatana M, Giri CC, Ansari MA, Elango C, Singh AK, Singh I, Khan I. Inhibition of NF-kappaB activation by 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors protects brain against injury in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. J Neuroinflammation. 2006;11:3–12. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furstenberger G, Krieg P, Muller-Decker K, Habenicht AJ. What are cycloxygenases and lipoxygenases doing in the driver's seat of carcinogenesis? Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2247–2254. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tavolari S, Bonafe M, Marina MM, et al. A dual COX/5-LOX inhibitor induces apoptosis in HCA-7 colon cancer cells through the mitochondrial pathway independently from its ability to affect the arachidonic acid cascade. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:371–380. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hersberger M. Potential role of the lipoxygenase-derived lipid mediators in atherosclerosis; leukotrienes, lipoxins and resolvins. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2010;48:1063–1073. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2010.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294:1871–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nie D, Honn KV. Cyclooxygenase, lipoxygenase and tumor angiogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:799–807. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8468-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong J, Bose M, Ju J, Ryu JH, Chen X, Sang S, Lee MJ, Yang CS. Modulation of arachidonic acid metabolism by curcumin and related beta-diketone derivatives: effects on cytosolic phospholipase A(2), cyclooxygenases and 5-lipoxygenase. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1671–1679. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuyama M, Yoshimura R. The target of arachidonic acid pathway is a new anticancer strategy for human prostate cancer. Biologics: Targets and Therapy. 2:725–732. doi: 10.2147/btt.s3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brash AR. Lipoxygenases: occurrence, functions, catalysis, and acquisitions of substrate. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23769–23682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamamoto S, Suzuki H, Nakamura M, Ishimura K. Arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase isozymes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;447:37–44. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4861-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shureiqi I, Lippman SM. Lipoxygenase modulation to reverse carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6307–6312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillis JW, Horrocks LA, Farooqui AA. Cyclooxygenases, lipoxygenases and epoxygenases in CNS: their role and involvement in neurological disorders. Brain Res Rev. 2006;52:201–243. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prasad VVTS, Nithipatikom K, Harder DR. Ceramide elevates 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid levels and upregulates 12-lipoxygenase in rat primary hippocampal cell cultures containing predominantly astrocytes. Neurochem Int. 2008;53:220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marks F, Furstenberg G. Eicosanoids and cancer. In: Marks F, Furstenberger G, editors. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Other Eicosanoids: From Biogenesis to Clinical Applications. Wiley VCH; Weinheim: 1999. pp. 303–330. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuendet M, Pezzuto JM. The role of cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase in cancer chemoprevention. Drug Metabol Drug Interact. 2000;17:109–157. doi: 10.1515/dmdi.2000.17.1-4.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones R, Adel-Alvarez LA, Alvarez OR, Broaddus R, Das S. Arachidonic acid and colorectal carcinogenesis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;253:141–149. doi: 10.1023/a:1026060426569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dannenberg AJ, Subbaramaiah K. Targeting cyclooxygenase 2 in human neoplasia: rationale and promise. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:431–436. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pratico D, Zhukareva V, Yao Y, Uryu K, Funk CD, Lawson JA, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY. 12/15-Lipoxygenase is increased in Alzheimer's disease: possible involvement in brain oxidative stress. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1655–1662. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63724-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yao Y, Clark CM, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY, Pratico D. Elevation of 12/15-lipoxygenase products in AD and mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:623–626. doi: 10.1002/ana.20558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harats D, Shaish A, George J, Mulkins M, Kurihara H, Levkovitz H, Sigal E. Overexpression of 15-lipoxygenase in vascular endothelium accelerates early atherosclerosis in LDL receptor – deficient mice. Arterioscl Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2100–2105. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.9.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi Y, Zhu H, Yoshimoto T. Essential roles of lipoxygenases in LDL oxidation and development of atherosclerosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:425–431. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quintana LF, Guzman B, Collado S, Claria J, Poch E. A coding polymorphism in the 12-lipoxygenase gene is associated to essential hypertension and urinary 12(s)-HETE in hypertension. Kidney Int. 2006;69:526–530. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Musiek ES, Breeding RS, Milne GL, Zanoni G, Marrow JD, McLaughlin B. Cyclopentenone isoprostanes are novel bioactive products of lipid oxidation which enhance neurodegeneration. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1301–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hao CM, Breyer MD. Physiologic and pathophysiologic roles of lipid mediators in the kidney. Kidney Int. 2007;71:1105–1115. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howe LR, Dannenberg AJ. A role for cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Semin Oncol. 2002;29(Suppl 11):111–119. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.34063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nie D, Krishnamoorthy S, Jin R, Tang K, Chen YC, Qiao Y, Zacharek A, Guo Y, Milanini J, Page G, Honn KV. Mechanisms regulating tumor angiogenesis by 12-lipoxygenase in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18601–18609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601887200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen FL, Wang XZ, Li JY, Yu P, Huang Y, Chen ZX. 12-Lipoxygenase induces apoptosis of human gastric cancer AGS cells via the ERK1/2 signal pathway. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:181–187. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9841-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhattacharya S, Mathew W, Jayne DG, Plengaris S, Khan M. 15-Lipoxygenase-1 in colorectal cancer: a review. Tumor Biol. 2009;30:185–199. doi: 10.1159/000236864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.You J, Mi D, Zhou X, Qiao L, Zhang H, Zhang X, Ye L. A positive feedback between activated extracellularly regulated kinase and cyclooxygenase/lipoxygenase maintains proliferation and migration of breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1607–1617. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao X, Grignon DJ, Chbhi T, Zacharek A, Chen YQ, Sakr W, Porter AT, Crissman JD, Pontes JE, Powell IJ, Honn KV. Elevated 12-lipoxygenase mRNA expression correlates with advanced stage and poor differentiation of human prostate cancer. Urology. 1995;46:227–237. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang WG, Douglas-Jones A, Mansel RE. Levels of expression in lipoxygenases and cyclooxygenase-2 in human breast cancer. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2003;69:275–281. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(03)00110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohammad AM, Abdel HA, Abdel W, Ahmed AM, Weel T, Eimen G. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and 12-lipoxygenase in human breast cancer and their relationship with HER-2/neu and hormonal receptors: impact on prognosis and therapy. Indian J Cancer. 2009;43:163–168. doi: 10.4103/0019-509x.29421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krueger JS, Keshamouni VG, Atanaskova N, Reddy KB. Temporal and quantitative regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) modulates cell motility and invasion. Oncogene. 2001;20:4209–4218. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou X, Lin Y, You J, Zhang X, Ye L. Myosin light-chain kinase contributes to the proliferation and migration of breast cancer cells through crosstalk with activated ERK 1/2. Cancer Lett. 2008;270:312–327. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan W, Wu J, Zhang X, Guo Y, Liu J, Sun T, Zhang B, Zhao D, Yang M, Yu D, Lin D. Association of functional polymorphisms in cyclooxygenase-2 and platelet 12-lipoxygenase with risk of occurrence and advanced disease status of colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1197–1201. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller S, Dykes D, Polesky H. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goodman JE, Bowman ED, Chanock SJ, Alberg AJ, Harris CC. Arachidonate lipoxygenase (ALOX) and cyclooxygenase (COX) polymorphisms and colon cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:2467–2472. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gong Z, Hebert JR, Bostick RM, Deng Z, Hurley TG, Dixon DA, Nitcheva D, Xie D. Common polymorphisms in 5-lipoxy-genase and 12-lipoxygenase genes and the risk of incident, sporadic colorectal adenoma. Cancer. 2007;109:849–857. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim T, Kim HJ, Park JK, Kim JW, Chung JH. Association between polymorphisms of arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase (ALOX12) and schizophrenia in a Korean population. Behav Brain Functions. 2010;6:44. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-6-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fridman C, Ojopi EP, Gregório SP, Ikenaga EH, Moreno DH, Demetrio FN, Guimarães PE, Vallada HP, Gattaz WF, Dias Neto E. Association of a new polymorphism in ALOX12 gene with bipolar disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;253:40–43. doi: 10.1007/s00406-003-0404-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Danaei G, Hoorn SV, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Ezzati M. Causes of cancer in the world: comparative risk assessment of nine behavioral and environmental risk factors. Lancet. 2005;366:1784–1793. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67725-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts and Figures 2008. Atlanta. American Cancer Society; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Porter PL. Global trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality. Salud Public Mex. 2009;(Suppl 2):141–146. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342009000800003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235:177–182. doi: 10.1126/science.3798106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morrow KPH, Zambrana F, Esteva FJ. Advances in systemic therapy for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:209. doi: 10.1186/bcr2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lynch HT, Silva E, Snyder C, Lynch JF. Hereditary breast cancer: Part I. Diagnosing hereditary breast cancer syndromes. Breast J. 2008;14:3–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2007.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matsuyama M, Yoshimura R. The target of arachidonic acid pathway is a new anticancer strategy for human prostate cancer. Biologics. 2008;294:725–732. doi: 10.2147/btt.s3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Y, Freedman BI, Kathryn P, Burdon KP, Langefeld CD, Howard T, Herrington D, Goff DC, Jr, Bowden DW, Wagenknecht LE, Hedrick CC, Rich SS. Association of arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase genotype variation and glycemic control with albuminuria in type 2 diabetes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:242–250. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu LP, Recker RR, Deng HW, Dvornyk V. ALOX12 gene is associated with the onset of natural menopause in white women. Menopause. 2010;17:152–156. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181b63c68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guo Y, Zhang X, Ta W, Miao X, Sun T, Zhao D, Lin D. Platelet 12-lipoxygenase Arg261Gln polymorphism: functional characterization and association with risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in combination with COX-2 polymorphisms. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17:197–205. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328010bda1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aleem AM, Jankun J, Dignam JD, Walther M, Kohn H, Svergun D, Skrzypczak-Jankun E. Human platelet 12-lipoxygenase, new findings about its activity, membrane binding and resolution structure. J Mol Biol. 2007;376:193–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aleem AM, Wells L, Jankun J, Walther M, Kohn H, Reinartz J, Skrzypczak-Jankun E. Human platelet 12-lipoxygenase: Naturally occurring Q261/R261 variants and N544L mutant show altered activity but unaffected substrate binding and membrane association behavior. Int J Mol Med. 2009;24:759–764. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pidgeon GP, Kandouz M, Meram A, Honn KV. Mechanisms controlling cell cycle arrest and induction of apoptosis after 12-lipoxygenase inhibition in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2721–2727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Flavin DFA. Lipoxygenase inhibitor in breast cancer brain metastases. J Neurooncol. 2007;82:91–93. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nigam S, Zafiriou MP, Deva R, Ciccoli R, Roux-Van der Merwe R. Structure, biochemistry and biology of hepoxilins: an update. FEBS J. 2007;274:3503–3512. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pidgeon GP, Lysaght J, Krishanamoorthy S, Reynolds JV, O'Byrne K, Nie D, Honn KV. Lipoxygenase metabolism: roles in tumor progression and survival. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:503–524. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Choi CK, Sukhthankar M, Kim CH, Lee SH, English A, Kihm KD, Baek SJ. Cell adhesion property affected by cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase: opto-electric approach. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:1385–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ma K, Nunemaker CS, Wu R, Chakrabarti SK, Taylor-Fishwick DA, Nadler JL. 12-Lipoxygenase products reduce insulin secretion and {beta}-cell viability in human islets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:887–892. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]