Cellular delivery of drugs and biomolecules (e.g. proteins and siRNA) is a central issue in biomedicine.[1] Promising delivery vehicles based on nanoparticles have been investigated as vectors.[2] Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are promising candidates for cellular delivery due to their low toxicity, biocompatibility and tunable surface functionalities.[3] Many studies have been carried out to understand the cellular uptake of AuNPs and the physico-chemical properties, such as size,[4] shape,[4a, 5] and surface chemistry,[5–6] that influence uptake. For example, Chan et al.[4a] have demonstrated the size dependence of cellular uptake, and our group has shown the role of surface charge and hydrophobicity on uptake.[6a] Tailoring the size and surface chemistry of AuNPs provides structural diversity,[7] allowing direct control over the physico-chemical properties of the particle surface that enable cellular delivery.[4d, 6a,8]

The evaluation of protein adsorption on nanoparticle surface is recognized as an important element in an assessment of NP applications in cellular delivery and therapeutics.[9] For example, for biomaterials used as medical implants the nature of the deposited protein layer onto these medical devices is responsible for the early immunological response in patients.[10] When NPs enter a biological fluid (e.g., blood), they are also likely to be readily coated with proteins. NP interactions with plasma proteins will then influence the uptake, biodistribution, excretion, delivery efficacy and/or toxicity of NPs inside the body.[11] Consequently, many studies have been conducted to study protein adsorption on various NPs.[12] For example, Douglas et al. systematically quantified the binding constants between different sized AuNPs and common human blood proteins.[13] Dawson et al. identified serum proteins that adsorb onto NPs using mass spectrometry, and in their work, they correlated particle size and surface hydrophobicity with the types of proteins that adsorbed.[14] Very few studies, however, have investigated how serum protein adsorption on NP surfaces influences the cellular uptake of NPs. Here, we describe experiments in which the effect of serum on the cellular uptake of 14 different AuNPs (Figure 1) is examined. From these experiments we are able to correlate the interplay between AuNP surface properties and protein adsorption on cellular uptake. We find that surface hydrophobicity is a critical factor for controlling serum albumin binding, which in turn decreases the cellular uptake of AuNPs.

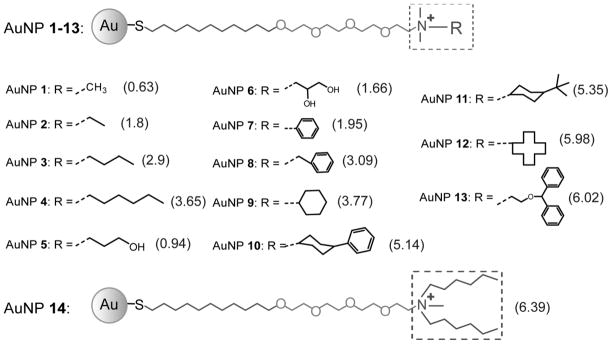

Figure 1.

Structural illustrations of the gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) used in the study. LogP values are shown in parentheses, and representing the hydrophobicity of the head groups shown in the dash square. These values were calculated with Maestro 8.0 using a MM force field.[15]

A series of AuNPs were synthesized featuring the same core size (~2 nm) and positive charge but bearing chemical functionalities of varying hydrophobicity (Figure 1). Functional groups displayed at the AuNP surface are composed of a quaternary amine that provides the particle surface with a permanent positive charge to promote solubility and facilitate cellular interactions, and an R group, which is varied to confer different degrees of hydrophobicity to the AuNP surface. Recently, we computationally predicted n-octanol/water partition coefficient of the ligand headgroups (the dashed squares in Figure 1) as the quantitative descriptor of relative nanoparticle surface hydrophobicity.[15] Log P values were estimated using MacroModel (Maestro 8.0 using the Merck Molecular Force Field (MMFF94).[15]

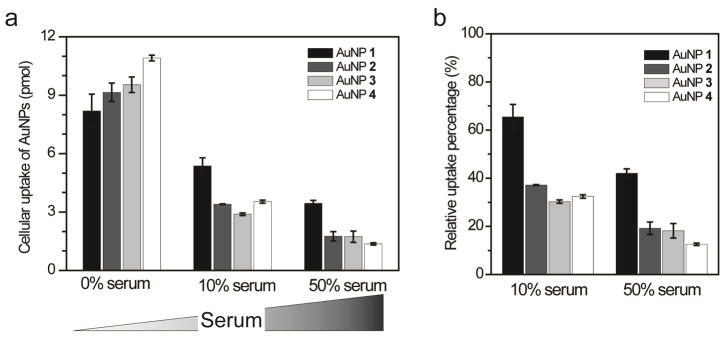

To illustrate the effect of AuNP hydrophobicity on cellular uptake, AuNPs 1–4 are used as examples. AuNPs 1–4 have the same essential quaternary amine structure with a fixed positive charge, but the different alkane chain lengths confer varying degrees of hydrophobicity, with LogP values that vary from 0.63 for AuNP 1 to 3.65 for AuNP 4. The uptake of these four AuNPs (50 nM each) by HeLa cells was examined by incubating the cells and AuNPs in the presence of different percentages of added serum, i.e., 0%, 10%, and 50% v/v, for six hours. Inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) was then used to measure the cellular uptake of these AuNPs, and the results are shown in Figure 2. The data clearly show that the presence of serum alters the extent of uptake (Figure 2a). For example, when the 10% serum is added to the culture medium, the cellular uptake of each AuNP is significantly decreased when compared to experiments in which no serum is added. Figure 2b shows that this uptake is decreased by about 35 to 70% depending on the hydrophobicity of the AuNP surface. Increasing the serum supplement in the media to 50% leads to further uptake suppression.

Figure 2.

(a) Cellular uptake of AuNPs 1–4 into HeLa cells that are incubated with different percentages of fetal bovine serum (FBS) supplements (0%, 10%, and 50% v/v) in the cell culture media. In each case, 50 nM of AuNP was added, and the incubation time was 6 h. (b) Relative uptake percentages of AuNPs by HeLa cells by comparing cellular uptake in FBS supplemented media (10% or 50% v/v) with no FBS supplemented media. The experiments were performed in triplicate. Error bars represent standard deviations of these measurements.

Examining the cellular uptake data more closely we find that the degree of uptake reduction is directly related to the hydrophobicity of the R group on each AuNP (Figure 2b). The uptake of AuNP 4, which is the most hydrophobic, is most affected by the serum supplements, with its uptake reduced to 32 ± 1 % (10 % serum supplement) and 13 ± 1% (50 % serum supplement) as compared to the experiments in which no serum was added. In contrast, the least hydrophobic AuNP 1 is only reduced to 65 ± 5% and 42 ± 2 %, respectively, when 10% and 50% serum is added to the culture medium. The uptake percentages for AuNP 2 and 3 in the presence of serum fall in between the values for AuNP 1 and 4, which is consistent with their intermediate hydrophobicities.

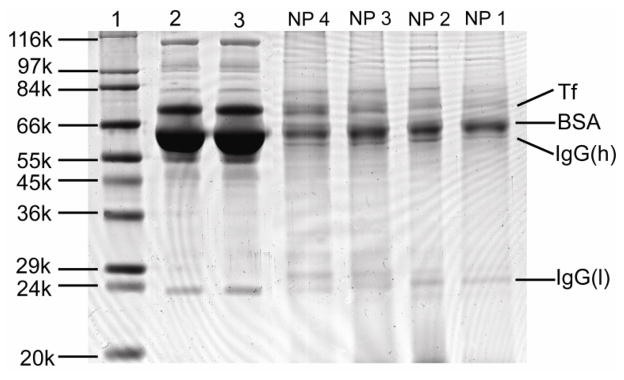

As other studies have revealed, AuNPs in cell culture media containing serum supplements are readily coated with serum proteins.[12b] The AuNP-protein complexes are thought to be an integrated biological entity that takes part in the cellular uptake process.[9] The data in Figure 2 clearly shows that AuNP uptake is reduced by the presence of serum proteins. To qualitatively characterize serum protein adsorption on the AuNPs, we separated the AuNP-protein complexes that result from 6 h incubation with serum and identified adsorbed proteins. Each of the four AuNPs in Figure 2 (i.e. AuNPs 1–4) were incubated with 50% serum supplemented media for 6 h in the absence of cells, and the AuNP-protein complexes were collected by centrifugation. The AuNPs in the collected complexes were then dissolved using NaCN solutions, releasing the adsorbed proteins into solution. The proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE (see experimental section for details). The results reveal (see Figure 3) that several different proteins adsorb to the AuNP surfaces, but bovine serum albumin (BSA), immunoglobulin G (IgG), and transferrin (Tf) are the most abundant proteins found on AuNPs. The results are not surprising as these three proteins are the most abundant proteins in serum, accounting more than 90% mass of the serum proteins.[12b] It seems likely that these three highly-abundant proteins coat the AuNPs, thereby mediating the interactions of these AuNPs with cells and decreasing their cellular uptake efficiency.

Figure 3.

SDS-PAGE of serum proteins adsorbed on AuNPs 1–4: Lane 1: molecular weight marker; Lane 2: serum, Lane 3, serum after the removal of AuNPs by centrifugation. The lanes labelled with NP 4, NP 3, NP 2, and NP 1 correspond to the proteins adsorbed to the corresponding AuNPs after incubating the AuNPs with 50% FBS for 6 hours. Tf: Transferrin; BSA: Bovine serum albumin; IgG: Immunoglobulin G; IgG(h): heavy chain of IgG; IgG(l): light chain of IgG.

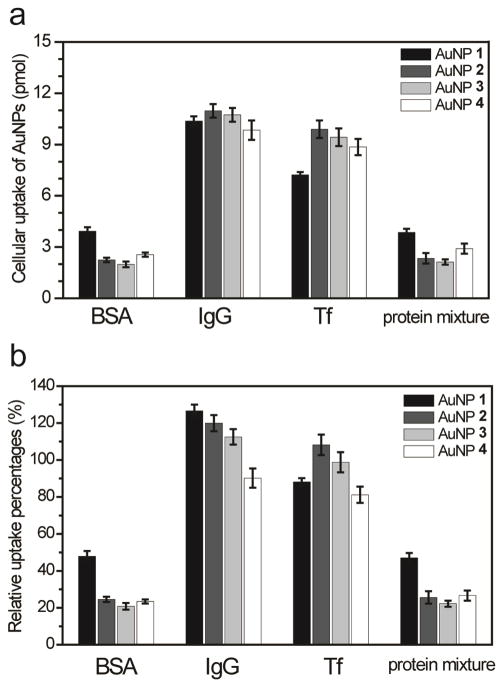

To further clarify the effect of these three proteins on AuNP uptake, we incubated HeLa cells and AuNPs 1–4 in media that was supplemented with BSA, IgG, and/or Tf instead of serum. The added protein amounts were 25 mg/mL (BSA), 5 mg/mL (IgG), and 2 mg/mL (Tf), which are close to 50% of the concentrations of these proteins in normal serum.[12b] Cellular uptake was again measured by ICP-MS, and the data are shown in Figure 4. Clearly, the addition of IgG or Tf has relatively little effect on the cellular uptake of AuNPs. As compared the uptake from media with no protein added, AuNP uptake in the presence of IgG or Tf is only marginally affected with uptake percentages ranging from 80% to 120%. In contrast, the addition of BSA decreases AuNP uptake dramatically. AuNP uptake is reduced to 20 to 45% of its amount when no protein was added to the media. Indeed, the results with BSA are very similar to the update data from media supplemented with 50% serum (i.e. Figure 2b). Adding all three proteins together confirms the results of the individual protein experiments in that AuNP uptake is similar to that with BSA alone, further proving that the major suppression effect is from BSA, not IgG or Tf.

Figure 4.

(a) Cellular uptake of AuNPs (1–4) into HeLa cells from media containing individual serum proteins. The concentrations of each of the three major serum proteins were 25 mg/mL (BSA), 5 mg/mL (IgG), and 2 mg/mL (Tf). The protein mixture refers to a cell media containing a mixture of all three proteins at the same concentrations used in the experiments with the individual proteins. (b) Relative uptake percentages of AuNPs by HeLa cells by comparing the cellular uptake in protein supplemented media and no protein supplemented media. The experiments were performed in triplicate. Error bars represent standard deviations of these measurements.

Our previous ITC experiments demonstrated that the binding constants for BSA[16] with AuNP 1 and AuNP 4 are 3.7 × 107 M−1 and 9.6× 107 M−1, respectively, with ~2 BSA molecules per nanoparticle regardless of affinity[17] Serum albumin is well known to have hydrophobic pockets that enable it to bind hydrophobic molecules in serum,[18] which probably explains its higher affinity for the more hydrophobic AuNP 4. However it is unclear whether BSA is simply adsorbed on particle surface or embedded inside the monolayer of AuNPs. When we mix AuNPs with media containing serum or BSA, the more hydrophobic AuNPs bind BSA with greater avidity, effectively inhibiting direct interactions between the cells and the AuNPs. The inhibition effect presumably comes from the repulsive interaction between anionic BSA and the negatively-charged cell membrane. This tighter binding of the more hydrophobic AuNPs to BSA likely explains the greater reduction in the cellular uptake of the more hydrophobic AuNPs. It should be noted, though, that binding of BSA does not provide a complete quantitative explanation for the lower uptake of the more hydrophobic AuNPs in serum. Upon comparing Figures 2b and 4b, it is clear that other components in serum reduce the uptake of the AuNPs further than BSA alone. When supplemented with 50% serum, the cellular uptake of AuNPs 2–4 is reduced to 19 ± 3%, 18 ± 3 % and 13 ± 1% (Figure 2b), respectively, while when supplemented with BSA alone, the cellular uptake of these AuNPs is reduced to 24 ± 2%, 20 ± 2 %, and 23 ± 1% (Figure 4b), respectively. It is possible that other low abundant proteins, such as apolipoproteins, may also bind the hydrophobic AuNPs in ways that reduce cellular uptake.[19]

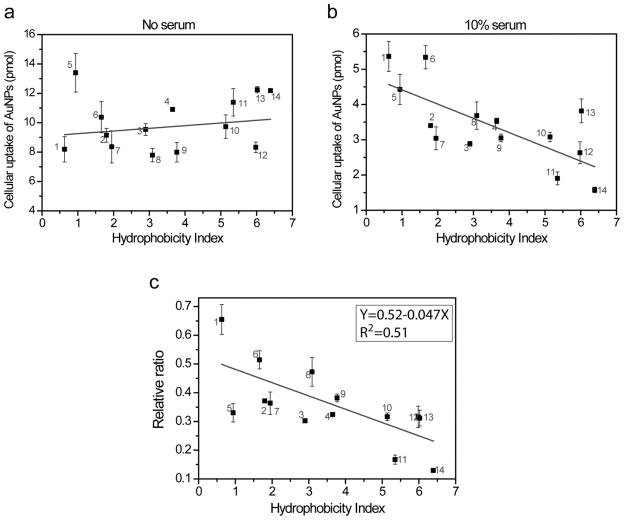

To further evaluate the trend that hydrophobic AuNP uptake is modulated by the presence of serum proteins, we examined 11 additional AuNPs featuring different surface hydrophobicities (see Figure 1). We measured the cellular uptake of these AuNPs into HeLa cells with and without the presence of 10% serum in the media (Figure 5). With no serum present in the media, cellular uptake of these AuNPs is independent of hydrophobicity (Figure 5a), which is the same trend noted with AuNPs 1–4 in Figure 2a. In contrast, the presence of 10% serum in the cell culture media influences the cellular uptake of many of the AuNPs (Figure 5b). If the relative uptake ratios with and without serum are calculated, it becomes clear that the more hydrophobic AuNPs are affected to a greater degree by the presence of the serum proteins as shown in Figure 5c. A linear trend line is also fitted to correlate the decreased cellular uptake amounts with hydrophobic index (Equation in Figure 5c inset). Overall, these data suggest that hydrophobic AuNPs form stronger AuNP-protein complexes, and these complexes inhibit the cellular uptake of these AuNPs.

Figure 5.

(a, b) Cellular uptake of AuNPs into HeLa cells without (a) and with (b) FBS supplements in the cell culture media. The hydrophobicity index of each AuNP was shown in Scheme 1. (c) Correlating AuNP surface hydrophobicity with the capability of cellular uptake. We calculated relative ratios between cellular uptake amount with and without serum addition in media. A linear trend line was fitted using Origin 8.0, and the fitted equation is shown in inset. The experiments were performed in triplicate. Error bars represent standard deviations of these measurements.

In summary, we have investigated how serum protein adsorption on NP surfaces influences the cellular uptake of NPs. We find that surface hydrophobicity is a critical factor for controlling serum albumin binding, which in turn decreases the cellular uptake of AuNPs. From these experiments we are able to correlate the interplay between AuNP surface property and protein adsorption on cellular uptake. Engineering the surface monolayer of nanoparticle provides another way to control the cellular uptake of nanoparticles, and helps to achieve better nanoparticle design for drug delivery and therapeutic purposes. However, more studies are necessary to explore the cellular uptake of AuNP-protein complexes at the molecular level. For example, it is still unclear whether the formed AuNP-protein complexes enter cells as an integrated entity or if the absorbed serum proteins are displaced from the AuNP during cellular uptake.

Experimental section

AuNP Synthesis

The Brust-Schiffrin two-phase synthesis method was used for synthesis of AuNPs with core diameters around 2 nm. After that, the Murray place-exchange method was used to obtain functionalized AuNPs. The syntheses of the ligands have been previous reported in the literature. [15]

Cell Culture and Cellular Uptake of AuNPs

HeLa cells (30,000 cells/well) were grown on a 24-well plate in low-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; glucose (1.0 g L−1)) supplemented with 0%, 10%, or 50% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotics (100 I.U./ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin). Cultures were maintained at 37°C under a constant humidity condition with 5% CO2. After 24 h of plating, the cells were washed three times with cold PBS, and the solutions of nanoparticles (50 nM) were added. Following 6 h of incubation, the cells were washed three times with PBS to remove extra nanoparticles and lysed for 15 min with a lysis buffer (Genlantis, USA). Each sample was prepared in triplicates.

ICP-MS Sample Preparation and Measurements and ICP-MS Instrumentation

All ICP-MS measurements were performed on a Perkin-Elmer Elan 6100. Operating conditions of the ICP-MS are listed below: rf power, 1200 W; plasma Ar flow rate, 15 L/min; nebulizer Ar flow rate, 0.96 L/min; isotopes monitored, 197Au and 103Rh (as an internal standard); dwell time, 50 ms; nebulizer, cross-flow; spray chamber, Scott.

Separation of adsorbed proteins on AuNP surfaces

Each of the AuNPs (500 nM) was incubated in 1800 μL of 50% serum supplemented media solution at 37°C for 6 h (the experiments with each AuNP were repeated three times). After 6 h, the AuNP-serum complex was centrifuged at 14000 rpm for 20 minutes and the collected precipitate was washed with water (2 × 200 μL). A solution of NaCN (300 μL, 300 mM) was then added to the AuNP-protein complex for decomposing the AuNPs. After sonication (20 minutes) the protein solution was transferred to 10000 MWCO filter and centrifuged for desalting at 12000 rpm for 15 minutes. Each sample was washed with water (2 × 200 μL) and then the filter was flipped and centrifuge at 4000 rpm for 4 minutes to collect the proteins. Finally, after evaporation of the samples using speed vac, 20 μL of water were added and the protein solution was used for SDS-PAGE separation.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the NIH (GM077173 and EB014277-01), and the NSF Center for Hierarchical Manufacturing (CMMI-1025020). The authors wish to thank Prof. Julian F. Tyson for the access to the ICP-MS instrumentation.

Contributor Information

Dr. Zheng-Jiang Zhu, Department of Chemistry, University of Massachusetts, 710 North Pleasant Street, Amherst, MA 01003 USA

Dr. Tamara Posati, Dipartimento di Chimica, Università di Perugia, Via Elce di Sotto 10, 06123 Perugia, Italy

Daniel F. Moyano, Department of Chemistry, University of Massachusetts, 710 North Pleasant Street, Amherst, MA 01003 USA

Rui Tang, Department of Chemistry, University of Massachusetts, 710 North Pleasant Street, Amherst, MA 01003 USA.

Bo Yan, Department of Chemistry, University of Massachusetts, 710 North Pleasant Street, Amherst, MA 01003 USA.

Prof. Richard W. Vachet, Email: rwvachet@chem.umass.edu, Department of Chemistry, University of Massachusetts, 710 North Pleasant Street, Amherst, MA 01003 USA

Prof. Vincent M. Rotello, Email: rotello@chem.umass.edu, Department of Chemistry, University of Massachusetts, 710 North Pleasant Street, Amherst, MA 01003 USA

References

- 1.Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, Farokhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R. Nature Nanotechnol. 2007;2:751. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De M, Ghosh PS, Rotello VM. Adv Mater. 2008;20:4225. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Giljohann DA, Seferos DS, Daniel WL, Massich MD, Patel PC, Mirkin CA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:3280. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Boisselier E, Astruc D. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:1759. doi: 10.1039/b806051g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ghosh P, Han G, De M, Kim CK, Rotello VM. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2008;60:1307. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Chithrani BD, Ghazani AA, Chan WCW. Nano Lett. 2006;6:662. doi: 10.1021/nl052396o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jiang W, KimBetty YS, Rutka JT, Chan WCW. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:145. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ma X, Wu Y, Jin S, Tian Y, Zhang X, Zhao Y, Yu L, Liang XJ. ACS Nano. 2011;5:8629. doi: 10.1021/nn202155y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Oh E, Delehanty JB, Sapsford KE, Susumu K, Goswami R, Blanco-Canosa JB, Dawson PE, Granek J, Shoff M, Zhang Q, Goering PL, Huston A, Medintz IL. ACS Nano. 2011;5:6434. doi: 10.1021/nn201624c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qiu Y, Liu Y, Wang L, Xu L, Bai R, Ji Y, Wu X, Zhao Y, Li Y, Chen C. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7606. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Zhu ZJ, Ghosh PS, Miranda OR, Vachet RW, Rotello VM. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14139. doi: 10.1021/ja805392f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cho EC, Xie J, Wurm PA, Xia Y. Nano Lett. 2009;9:1080. doi: 10.1021/nl803487r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hauck TS, Ghazani AA, Chan WCW. Small. 2008;4:153. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verma A, Stellacci F. Small. 2010;6:12. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Nativo P, Prior IA, Brust M. ACS Nano. 2008;2:1639. doi: 10.1021/nn800330a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lin J, Zhang H, Chen Z, Zheng Y. ACS Nano. 2010;4:5421. doi: 10.1021/nn1010792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lynch I, Salvati A, Dawson KA. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:546. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch I, Cedervall T, Lundqvist M, Cabaleiro-Lago C, Linse S, Dawson KA. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2007;134–35:167. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Sund J, Alenius H, Vippola M, Savolainen K, Puustinen A. ACS Nano. 2011;5:4300. doi: 10.1021/nn101492k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Monopoli MP, Walczyk D, Campbell A, Elia G, Lynch I, Bombelli FB, Dawson KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:2525. doi: 10.1021/ja107583h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Maiorano G, Sabella S, Sorce B, Brunetti V, Malvindi MA, Cingolani R, Pompa PP. ACS Nano. 2010;4:7481. doi: 10.1021/nn101557e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhu ZJ, Carboni R, Quercio MJ, Yan B, Miranda OR, Anderton DL, Arcaro KF, Rotello VM, Vachet RW. Small. 2010;6:2261. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Lynch I, Dawson KA. Nano Today. 2008;3:40. [Google Scholar]; (b) Aggarwal P, Hall JB, McLeland CB, Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2009;61:428. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Casals E, Pfaller T, Duschl A, Oostingh GJ, Puntes V. ACS Nano. 2010;4:3623. doi: 10.1021/nn901372t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lacerda SHDP, Park JJ, Meuse C, Pristinski D, Becker ML, Karim A, Douglas JF. ACS Nano. 2009;4:365. doi: 10.1021/nn9011187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lundqvist M, Stigler J, Elia G, Lynch I, Cedervall T, Dawson KA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moyano DF, Goldsmith M, Solfiell DJ, Landesman-Milo D, Miranda OR, Peer D, Rotello VM. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:3965. doi: 10.1021/ja2108905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrer ML, Duchowicz R, Carrasco B, de la Torre JG, Acuña AU. Biophys J. 2001;80:2422. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76211-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De M, Miranda OR, Rana S, Rotello VM. Chem Commun. 2009:2157. doi: 10.1039/b900552h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghuman J, Zunszain PA, Petitpas I, Bhattacharya AA, Otagiri M, Curry S. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:38. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cedervall T, Lynch I, Foy M, Berggård T, Donnelly SC, Cagney G, Linse S, Dawson KA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:5754. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]