Abstract

Recently we reported a cytoplasmic sodium overload to cause a severe osmotic oedema in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). Our results suggested that this dual overload of sodium ions and water precedes the dystrophic process and persists until fatty muscle degeneration is complete. The present paper addresses the questions as to whether these overloads are important for the pathogenesis of the disease, and if so, whether they can be treated. As a first step, we investigated the effects of various diuretic drugs on a cell model of DMD, i.e. rat diaphragm strips previously exposed to amphotericin B. We found that both carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and aldosterone antagonists were able to repolarise depolarised muscle fibres. Since carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are known to have acidifying effects and this might be detrimental to the ventilation of DMD patients, we mainly concentrated on the modern spironolactone derivative, eplerenone. This drug had a very high repolarizing power, the parameter considered by us as being most relevant for a beneficial effect. In a pilot study we administered this drug to a 22-yr-old female DMD patient who was bound to an electric wheelchair and has had no corticosteroid therapy before. Eplerenone decreased both cytoplasmic sodium and water overload and increased muscle strength and mobility. We conclude that eplerenone has beneficial effects on DMD muscle. In our opinion the cytoplasmic oedema is cytotoxic and should be treated before fatty degeneration takes place.

Key words: Duchenne muscular dystrophy, eplerenone, cytotoxic oedema

Introduction

A very conspicuous pathognomonic sign of early states of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is the disproportion between size and strength of the skeletal muscles, being most prominent in the enlarged calves. Duchenne himself addressed this sign in all his descriptions of the disease in the decade of 1860-1870, and finally decided to name the disease "paralysie musculaire pseudo-hypertrophique" (1). Today, 150 years later, the reason and origin of this enlargement is still a matter of debate. Previously a muscle oedema that could contribute to the enlargement was reported (2). Etiologically it was widely attributed to an interstitial inflammation.

Our own group became interested in this problem after we had identified an increased sodium and water content in chronically weak muscles of patients having hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HypoPP) (3). In our search for oedemas we used Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) with a Short-Tau Inversion Recovery (STIR) 1H MR sequence. We also had tackled the question as to whether these oedemas were of an interstitial or an intracellular kind by equipping our set-up with a 23Na MRI Inversion Recovery sequence (Na-IR) which partially suppresses the signal raised by free sodium in the extracellular fluid and thus mainly represents cytoplasmic sodium (4). In the HypoPP patients the nature of the oedema turned out to be cytotoxic.

With our experience in Paramyotonia and HypoPP patients we applied the same MRI techniques to Duchenne patients in order to unravel the question of pseudo-hypertrophy in this disease. A pilot study on 11 DMD patients suggested that also in this disease muscular sodium and water content is increased, thus causing an osmotic oedema (5).

The main aim of the present study was to find a drug for the treatment of the oedema in DMD. Again, we were guided by our findings with periodic paralysis patients: chronic weakness of HypoPP patients was improved by acetazolamide (3) while episodic weakness of HyperPP patients was relieved by both hydrochlorothiazide and acetazolamide (6).

Acetazolamide repolarised electrically depolarised muscle fibres and this in vitro effect was considered to be responsible for the in vivo effects on MRI and on muscle strength (3). Since acetazolamide is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, it exerts acidifying effects resulting in respiratory depression. Therefore carbonic anhydrase inhibitors might be contraindicated in DMD. Similarly inappropriate might be hydrochlorothiazide because of its K+ wasting effects which would contribute to muscle weakness.

Therefore we were searching for another diuretic agent. Guided by the experience that spironolactone has favourable effects on episodic (7) and chronic weakness (3) in HypoPP, an aldosterone antagonist was taken into consideration. As eplerenone has a higher affinity to the mineralocorticoid receptor and a lower to sexual hormone receptors than spironolactone, it was taken for further testing. Before administering eplerenone to a patient we first tested the repolarizing drug on a cellular DMD model. Since the results with the model were very promising, we treated the marked oedema of a female, wheelchair-bound DMD patient who never had corticosteroid medication.

Patients, material and methods

Patients

A 24-yr-old female patient with genetically proven DMD gave written informed consent to treatment with eplerenone. The study was approved by the local review board and conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki in the present form. To determine the time duration of the ion and water imbalance until dystrophy, the results published by Weber et al. (5) on 10 DMD boys were revisited.

MR imaging protocol

The imaging protocol of the lower legs comprised axial T1-weighted turbo spin-echo for the detection of fatty muscle degeneration and axial short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) 1H MR sequences for the identification of the oedema. The muscle oedema was normalized to the background signal.

A 23Na pulse inversion recovery weighted the sodium signal towards intracellular 23Na by partially suppressing the signal received from the extracellular space (4). Two reference phantoms were additionally investigated for control reasons. One was filled with 51.3 mM NaCl solution to mimic Na+ with unrestricted mobility (e.g. within extracellular fluid), the other one was filled with 51.3 mM NaCl in 5% agarose to mimic Na+ with restricted mobility as in the myoplasm. For normalization of the 23Na signals, the values of the soleus muscles were divided by the signal intensity of the agarose in which NaCl was trapped.

The cross-sectional area of the calves was measured on T1-weighted MR images using a predefined tool which calculates the area when the boundaries are outlined (Picture Archiving and Communication System, PACS). The area contained not only muscle tissue but also the oedema as well as the tibial and fibular bones and excluded subcutaneous fat tissue (8).

Measurement of resting membrane potentials on excised rat muscle specimens

Female Wistar rats were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation and their diaphragms removed and divided into several strips intact from tendon to tendon. The strips were prepared and stored in a solution containing 108 mM NaCl, 4.5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 0.7 mM MgSO4, 26.2 mM NaHCO3, 1.7 mM NaH2PO4, 9.6 mM Na-gluconate, 5.5 mM glucose, and 7.6 mM sucrose. At 37°C the pH was adjusted to 7.4 by gassing with 95% O2 and 5% CO2; osmolality was adjusted to 290 mosmol/l by NaCl variation. Before eplerenone testing was started, the specimen to be tested next was incubated for 30 min in a solution that differed from the dissecting solution by containing 6 instead of 4.5 mM KCl. This high K+ concentration allowed the fibres to take up potassium. Then the specimen was incubated in the experimental solution after another period of 30 min.

In accordance with previous measurements (3), the experimental solution contained amphotericin B (10 μM) as cation ionophore to cause a bimodal distribution of resting membrane potentials, i.e., polarised and depolarised, and to mimic dystrophic muscle. As the AB-induced sodium leak causes a subsarcolemmal ATP deletion, KATP channels become activated thereby causing a repolarization of an unpredictably large fraction of the specimen. To avoid the KATP channel activation, the specific KATP channel blocker glibenclamide (4 μM) was added to the experimental solution. The K+ concentration was 2.0 mM to facilitate the paradoxical depolarization.

To test the effect of eplerenone on the resting membrane potential Em and to determine its EC50, various eplerenone concentrations were used. Independent of the given eplerenone concentration, the dissolvent DMSO in the experimental solution always had a constant concentration of 2 ml/l. Em was recorded at room temperature, using microelectrodes (7-11 MΩ) and a voltage amplifier. Histograms of the potentials were smoothed by density estimation. The potentials exhibited a two-peak distribution of polarised fibres (defined as -70 mV and more negative) and depolarised fibres (-69 mV and less negative), displayed as probability density. Concentration-response curves were fitted to the measured potentials according using the equation frf = frfmin + (frf max-frfmin) / (1 + 10^((logEC50-[drug])n)) with frf as the fraction of repolarised fibers, frfmax and frfmin as the maximum and minimum effects, and n as the Hill coefficient.

In all statistical tests, an effect was considered to be statistically significant if the p-value was 0.05 or less. Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data.

Results

History and all medical reports of the female patient are given in the Appendix. A severe clinical course requiring spondylodesis (Fig. 1) and assisted ventilation at night, a chromosome X-to-17 translocation (breakpoint at Xp21, and immune histochemistry of a mosaicism had led to the diagnosis of DMD. As no medication had yet been administered, therapy options (glucocorticoids such as prednisolone or deflazacort versus the steroid eplerenone) were thoroughly discussed. The patient preferred the offlabel use with eplerenone that was administered in daily alternating doses of 25 and 50 mg. The usual dose of 50- 100 mg/d was avoided because of the low body weight of 35 kg. Originally we had planned a 4-weeks trial, however the absence of adverse effects and the general well-being under medication made the patient continuing the off-label use. At the time of submitting this paper she is still taking eplerenone, i.e. for 13 months now. All involved experts agreed to this extension since clinical re-assessments showed stable or improving cardiac, respiratory and motoric functions.

Figure 1.

X-ray of the female DMD patient after spondylodesis. The anterior-posterior and lateral x-rays of the whole spine show an extensive dorsal spondylodesis from third thoracic to first sacral vertebrae.

Clinical and MRI assessment of the female DMD patient before treatment (at age 22)

Before medication had been started, the female adult was examined clinically and by conventional and specific MRI. The DMD patient presented with a very low body mass index of 11, a severe generalized muscle atrophy including facial muscles, scapulae alatae, and swallowing difficulties, and borderline ability to stand or to walk. Circumferences of the arms and forearms were smaller on the right (15 and 14 cm) than on the left side (21 and 19 cm). The motoric abilities were just sufficient for a safe transfer from wheelchair to bed and vice versa. All limb muscles were weaker on the right side (proximally MRC 2, distally MRC 3) than on the left (proximally MRC 3, distally MRC 4). The deep tendon reflexes could be elicited only in the triceps surae muscles. Details on the clinical status are given in the Appendix.

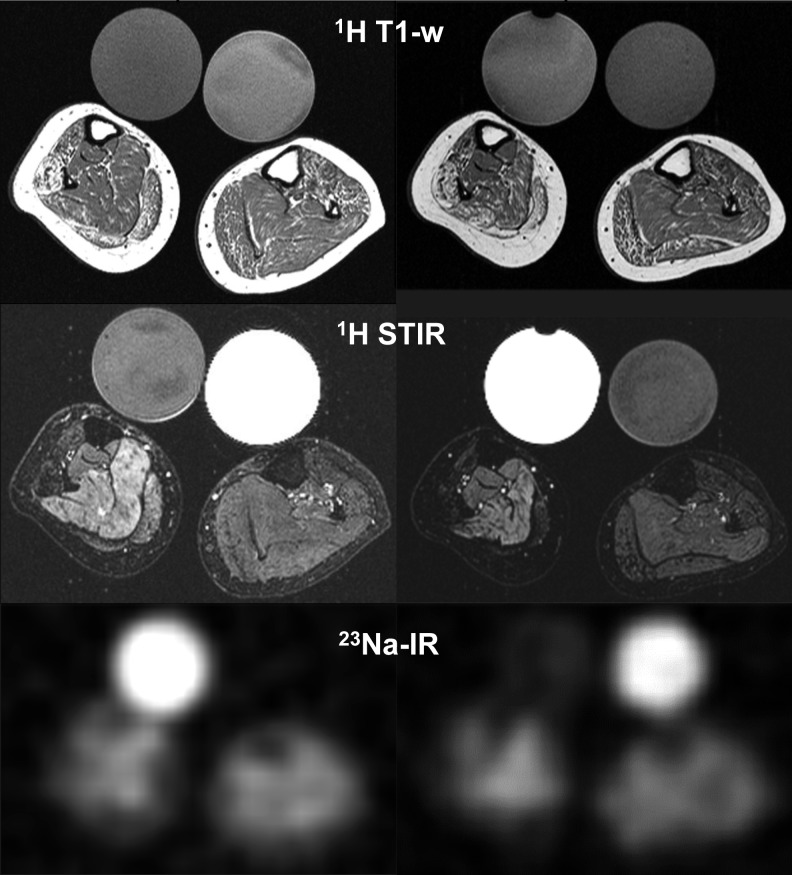

According to the asymmetric clinical impairment, the MR images of the lower legs displayed major side differences regarding degeneration and oedema (Fig. 2). Both sodium signals and water content were strikingly increased (Fig. 2, Table 1).

Figure 2.

MRI of the lower legs of the female DMD patient without and with eplerenone. In the T1-weighted MRI sequences (1H T1-w), the patient's muscles showed a moderate fatty degeneration with a markedly pronounced (pseudo) hypertrophy before treatment with eplerenone (left). The fat-suppressed MRI sequences (1H STIR) displayed an oedema that is reduced after treatment for 11 months (right). The 23Na inversion recovery sequence exhibited higher signal intensities before treatment (left). The quantitative values for oedema and Na-signals are given in Table 1. Note that the right side of the patient is more affected than the left (smaller circumference, pronounced oedema). The bright circles in 23Na-IR reflect the 23Na signal of 51.3 mM NaCl trapped in 5% agarose while the signal of the contralateral tube containing an aequimolar NaCl solution is suppressed in the 23Na-IR sequence but bright in the 1H- STIR sequence.

Table 1.

Eplerenone effects of the lower leg muscles of the female DMD patient. Oedema relative to background signal. Muscle strength graded according to MRC.

| Visit [#] | 23Na signal | Oedema [STIR ratio] right soleus | Knee flexion/ extension right//left leg | Foot dorsi-/ plantarflexion right//left leg | Calf cross-sectional area [mm2] right//left leg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.8 | 21.2 | 2/2//3/3 | 3/4//3/4 | 3,237//3,947 |

| 2 | 0.7 | 19.6 | 2/3//3/4 | 3/4//4/4 | 2,781//3,490 |

| 3 | 0.7 | 18.8 | 3/3//4/4 | 3/4//4/5 | 2,509//2,890 |

Some of the data are given in Weber et al., J Neurol 2012, DOI 10.1007/s00415-012-6512-8.

Clinical features and MRI following treatment with eplerenone for 5 and 11 months

Beyond the effects of eplerenone on muscle sodium and oedema, the following clinical alterations have been documented at the assessment following treatment with eplerenone for 11 months: the patient reported no adverse effects; speaking was improved, the circumferences of both forearms were increased by 1 cm while those of both upper and lower legs were smaller by 1 cm; of the 19 muscle groups the strength of which was evaluated manually, 10 were slightly stronger (by 1-2 MRC grades) and 4 were slightly weaker (by 1 MRC grade), the remaining 5 were unaltered. A handgrip dynamometer revealed constant maximum grip force of 20 kg upon the three MRI appointments. The serum potassium was always in the normal range. The total protein and quantitative albumin were at the upper normal limit; however protein was not determined at the first assessment.

In the MRI of the lower legs, both sodium and water content displayed some improvement, determined after 5 and 11 months of the treatment with eplerenone (Fig. 2, Table 1). In concordance with the MRI changes, muscle strength was slightly increased (Table 1).

Re-visiting the results of the DMD boys reported by Weber et al. (2011)

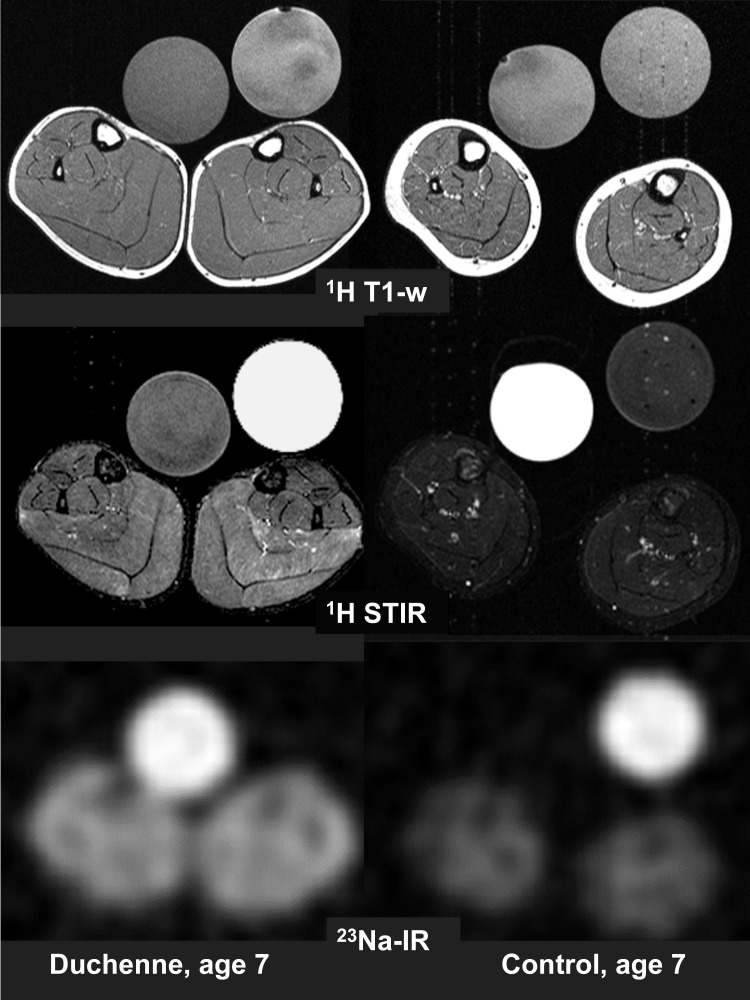

Of the 10 boys published by Weber et al. (5), all were older than 5 years. They all presented with a severe cytoplasmic sodium and water overload. The youngest boy presenting with obvious fatty muscle degeneration of the triceps surae muscles in the T1-weighted 1H-MR images was age 9 while all boys without degeneration were younger than 8 years. Despite the absence of dystrophy, they exhibited a reduced extensibility of hip, knee, and ankle joints and reduced leg abduction due to flexor muscle weakness and muscle contractures. The lower legs of one of them, aged 7, are shown by T1-weighted 1H-MRI, T2-weighted STIR 1H-MR, and 23Na-MRI (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

MRI of the lower legs of DMD and control, both age 7. Like in other DMD boys ≤ 7 years, the muscles revealed no fatty degeneration in the T1- weighted 1H-MRI sequence (1H T1-w). Compared to the control, his muscles are (pseudo)hypertrophic. As in all other DMD boys of any age, the fat-suppressed STIR 1H-MRI sequence displayed a marked oedema (1H STIR). The 23Na inversion recovery sequence exhibited markedly higher signal intensities in the muscles of the DMD boy than in the control (23Na-IR). The reference tubes show the same behaviour as in Fig. 2.

Effects of eplerenone and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors on resting membrane potentials Em

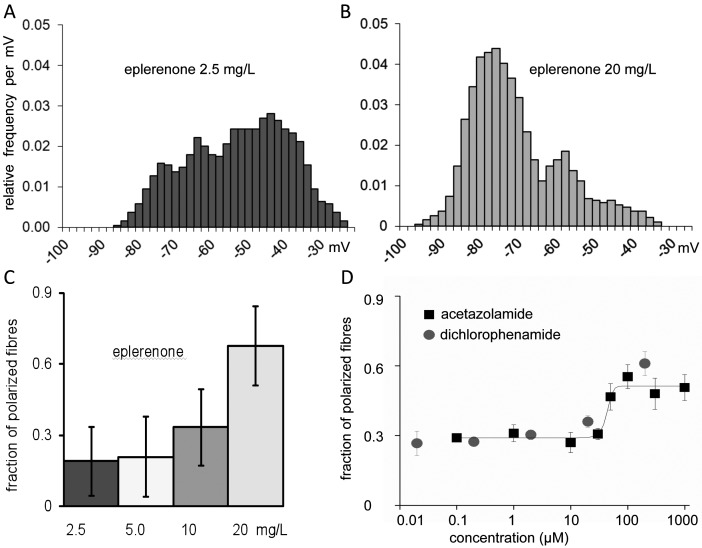

In the presence of subtherapeutical concentrations of eplerenone, the rat diaphragm muscle fibres kept in a solution for a dystrophic muscle model (see Methods) revealed a broad distribution of stable membrane potentials (Fig. 4A). Most fibres (70%) were depolarised (Em less negative than -70 mV) and paralyzed as consequence of the depolarization (membrane inexcitability due to inactivation of the voltage-gated sodium channels) (3). The remaining fibres had resting potentials even more negative than -70 mV or (polarised fraction). The addition of eplerenone in therapeutic concentrations shifted many fibres from the depolarised to the polarised state and thereby increased the fraction of polarised fibres (Fig. 4B). The concentration-response curve showed half-maximal effects (EC50) at approximately 15 mg/L eplerenone (36 μM, Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Eplerenone effects on rat muscle strips partially depolarised according to a dystrophy model. A, B: The histograms present the distribution of resting membrane potentials of excised muscle fibres after exposure to eplerenone in a very low concentration (left) and a therapeutic concentration (right) (3 strips à 35 fibres for each concentration). Note that the addition of eplerenone in therapeutic concentrations shifted many fibres from the depolarised to the polarised state and thereby increased the fraction of polarised fibres. The eplerenone exposure started 30 min prior to the first potential measurement and remained for about one hour that was required for the measurement of a strip. c: Histograms of the fibres in the polarised state for various eplerenone concentrations, yielding an EC50 of about 15 mg/L. D: Concentration-response curves for acetazolamide and dichlorophenamide (3-8 strips à 35 fibres for each concentration). Note that the fraction of polarised fibres is lower than for eplerenone.

Since acetazolamide had been found to repolarise depolarised fibres and to increase twitch force (3), we also tested dichlorophenamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor considered to have a higher potency. A comparison of the repolarisation power of the three drugs showed that eplerenone (70%) was superior dichlorophenamide (60%) and acetazolamide (50%). EC50 values were 40 μM for acetazolamide and about 25 μM for dichlorophenamide (Fig. 4D).

As the first membrane potential measurements of the strips did not differ from much later measured values, the effects of all three drugs must have occurred within the preincubation period of 30 minutes.

Discussion

The role of the oedema in DMD and its reduction by eplerenone

The marked oedema that is already detectable in boys before fatty degeneration takes place may at least partially explain the typical pseudohypertrophy of DMD calves. This "paralysie musculaire pseudohypertrophique" describes the disproportion between size and strength of the muscles (1). The oedema is mainly caused by the elevated cytoplasmic Na+ concentration and therefore is osmotic (5) and cytotoxic and not primarily interstitialinflammatory as usually assumed. The term 'transient oedema' should be avoided since the oedema is regularly observed, even in older DMD boys as long as muscle tissue has not been completely replaced by fat and fibrosis (5).

DMD is characterized by a gonosomal mode of transmission and therefore female DMD patients have rarely been reported (9). While most heterozygous female carriers of DMD mutations are asymptomatic, a few initially present with mild thigh weakness, myalgia or muscle cramps whereby later onset of symptoms suggests less severe disease (9). In the present patient, the early onset was in agreement with a severe DMD phenotype although a constant asymmetry in muscle atrophy and weakness is unusual for this diagnosis. The pronounced asymmetry in this female patient may be related to the mosaic pattern of muscle dystrophin.

The treatment of our female patient with eplerenone resulted in a reduction of the strikingly increased cytoplasmic sodium and water signals and in an increased strength and mobility. The reduction of the circumferences of the legs could reflect a decreased muscle mass or a decreased oedema. As the leg muscles became rather stronger than weaker and showed much less water content and no progression in dystrophy, we interpreted the reduced circumferences as result of washing out the oedema.

Rapid effects of eplerenone on muscle in vitro

The endogenous and exogenous ligands of the mineralocorticoid receptor have been known for long time to regulate sodium-potassium homeostasis in kidney, colon and salivary glands by transcriptional and translational effects on genes encoding the Na+/K+ ATPase (10) and the epithelial sodium channel, ENaC. Recently additional non-genomic effects of the ligands of the mineralocorticoid receptor in the skeletal muscle via kinases have been reported (11).

The in vitro effects of eplerenone described here are to our knowledge the first examples of both a direct and rapid (within few minutes) effect of a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist on a tissue, on top of that on the skeletal muscle which has not ever been discussed as a potential target of aldosterone or its antagonists. Eplerenone at the EC50 repolarised more fibres than acetazolamide or dichlorophenamide. Acetazolamide has been found to improve muscle strength, cytoplasmic sodium overload and oedema in HypoPP patients (3), and dichlorophenamide is currently being tested in a phase III trial on periodic paralysis patients.

An increased sodium conductance is primarily responsible for the depolarised membrane in both our cell model and DMD muscle (3, 12), the consequence is a cytoplasmic sodium overload that, if the sodium accumulation is osmotically relevant, causes an oedema. A membrane repolarization should recover ion and water homoeostasis and reconstitute membrane excitability and force. A possible endogenous mechanism to reduce sodium overload in muscle may be the sodium proton exchanger (NHE). In the heart muscle, NHE was identified as a mineralocorticoid-regulated inducer of inflammation and fibrosis (13). This regulation contributes to the beneficial effects of the steroid receptor blocker spironolactone which preserved cardiac and skeletal muscle function in mdx mice (14). The effects of eplerenone on the resting potential of cells mimicking DMD and our patient might be pathogenetically related to the effects of spironolactone.

Rationale for the preference eplerenone over spironolactone

Although both drugs are aldosterone antagonists, there are striking differences. Eplerenone, a 9α,11α- epoxy-derivative of spironolactone, is an effective and selective mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist. It is approved by the FDA for left-ventricular dysfunction following heart infarction. As an add-on to optimal medical therapy for patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by left ventricular dysfunction, it reduced morbidity and mortality (15). Other potential indications are antifibrotic effects in cardiac and smooth muscle, sarcopenia, cardiomyopathies, arterial hypertension, atherosclerosis, hepatic fibrosis, panic attacks, and cognitive impairment (16-21). Although eplerenone has not yet been tested for antifibrotic effects on skeletal muscle the positive results on cardiac and smooth muscle support a putative beneficial effect.

While spironolactone and its active metabolites (e.g. canrenone) have a high affinity to progesterone and androgen receptors, eplerenone has a very low affinity to these and other steroid receptors (22). This lesser affinity was achieved by replacing the 17-alpha-thioacetyl group of spironolactone with a carbomethoxy group (23). This reduced affinity to progesterone and androgen receptors makes eplerenone very appropriate as drug for DMD.

Eplerenone is further distinguished from spironolactone by its shorter half-life and the fact that it does not have any active metabolites. In the absence of a liver dysfunction and doses > 100 mg/d, the risk of hyperkalemia is much lower than with spironolactone (15). We conclude that eplerenone is a promising treatment in DMD, either as alternative or as add-on to glucocorticoids in DMD.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a research grant from the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Muskelkranke e.V. (DGM). F. Lehmann-Horn is endowed Senior Research Professor of the non-profit Hertie-Foundation. We are grateful to Dr. Reinhardt Rüdel for fruitful discussions and to Drs. Philipp Ehlermann and Wiebel for their commitment in taking care of the female DMD patient. Molecular genetics on this patient was performed by the Institute of Human Genetics, University Hospital, Heidelberg (Director: Prof. C.R. Bartram). At age 7, immune histochemistry of a muscle sample of the female DMD patient was evaluated by Dr. Mortier, Wuppertal. We thank the boys and their families and particularly the female patient for their participation.

Appendix

History and medical reports of the female patient

The female DMD patient had reached unassisted free walking as early as at age of 11 months. However she did not like to walk as she had frequent falls and difficulties in getting up. At age 2 she frequently complained of muscle pains, particularly in the thighs, during walking and even more so during longer periods of sitting. At age 6 she had a fracture of the forearm with subsequently reduced muscular force and atrophy. She did not participate in gymnastics at school.

The neuropaediatric examination at age 7 yielded a marked pseudo-hypertrophy of the calves, frequent falls when running and subsequently Gowers' manoeuvre. Heel gait was not possible; the muscle stretch reflexes were weak. Serum CK 1,852 U/l, LDH 431 U/l, GOT 58 U/l, GPT 126 U/l. The EMG displayed fibrillations, markedly shortened motor unit potentials, and a reduced amplitude at maximal innervation. Histology, enzyme histochemistry and morphometry of the muscle identified muscle fibre atrophy, hypertrophic fibres, fibrosis, necrosis, phagocytosis, and central nuclei in agreement with an active and chronic dystrophic process. Immune histochemistry revealed a mosaicism with some fibers having continuous membrane immunostaining, other fibers uniformly unstained, and some fibers with discontinuous or partial dystrophin staining. Molecular genetics identified a chromosome X-to-17 translocation (breakpoint at Xp21, for details see below).

From age 12 on the patient developed kyphoscoliosis with rapid progression. At age 14, when the lowermost right rib was touching the pelvis, a spondylodesis of the spinal column was performed. The stabilization of the spinal column was not complete and did not enable the patient to sit in an upright position. Since the patient complained of ischialgia and pain at the right sciatic bone, an MRI was performed that excluded compression of the sciatic nerve. From age 15 on, the patient used an electric wheelchair and, aged 16, assisted ventilation at night. Glucocorticoid therapy was discussed but refused by the mother. From age 20 on the patient used an orthesis for the right foot at night because of a developing talipes. Difficulties with drinking commenced and arthrosis and limited function of the right hand appeared. Multimodal pain therapy is performed because of back pain and ischialgia. The seat of her wheelchair needed repeated adjustments. Shortly prior to medication, hospitalisation was required because of a broncho-pulmonar infection with retention of mucus. Prophylactic administration of an ACE-inhibitor, e.g. ramipril 1.25 mg/d, was discussed but not executed.

Extended molecular genetics

Cosmids contained exons 3, 5-7, 44, 45, 46-47, 48 of the dystrophin gene hybridized to the translocated chromosome 17 and the normal X-chromosome. Exon 1 hybridized to both translocated chromosomes and the normal X-chromosome. Therefore, we assume that the translocation occurred somewhere in exon 1 of the dystrophin gene. Since an autosomal translocation usually stops the translocated X-chromosome from being inactivated, the normal X-chromosome was most likely inactivated. An inactivation test was performed from leucocyte DNA for the androgen receptor locus. Allele 1: 0-5% methylation, allele 2: 95-100% methylation. Skewed inactivation supports the inactivation of the normal X-chromosome, which explains the presence of DMD in the female. The mother of the patient displayed normal chromosomes. The father was unavailable for testing, but we assume he would have been symptomatic if the translocation had been present. The translocation was concluded to be a de-novo mutation.

Details on the clinical assessment of the female DMD patient before treatment

The female DMD patient presented with a very low body weight of 35 kg, height 169 cm, and foot swelling. She used a straw for drinking water because of swallowing difficulties; daily maximum intake was approximately one liter. The serum potassium was in the normal range. Assisted ventilation at night: Legendair, UM NS, aPVCV, IPAP 14, EPAP 0, frequency 12/min, I/E 1/1.7, trigger 2, ramp 2, Vtmin 250 ml. The cardiac MRI results were: no indication of cardiac involvement; systolic function of left ventricle at lower normal limit; myocardiac oedema excluded; no late enhancement after application of gadolinium as indicator of precedent myocardic infarction. Body plethysmography: VC 0.98 l (25%), FEV1 0.96 l (28%), Tiffeneau test 97%, TLC 4.2 l (78%).

References

- 1.Duchenne GBA. Recherches sur la paralysie pseudo-hypertophique ou paralysie myosclérosique. Archives Générales de Médicine. 1868;11:25–25. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marden FA, Connolly AM, Siegel MJ, et al. Compositional analysis of muscle in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy using MR imaging. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:140–148. doi: 10.1007/s00256-004-0825-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jurkat-Rott K, Weber MA, Fauler M, et al. K+ - dependent paradoxical membrane depolarization and Na+ overload, major and reversible contributors to weakness by ion channel leaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4036–4041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811277106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagel AM, Amarteifio E, Lehmann-Horn F, et al. 3 Tesla sodium inversion recovery magnetic resonance imaging enables improved visualization of intracellular sodium content changes in muscular channelopathies. Invest Radiol. 201;46:759–766. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e31822836f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber MA, Nagel AM, Jurkat-Rott K, et al. Sodium (23Na) MRI detects elevated muscular sodium concentration in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2011;77:2017–2024. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823b9c78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amarteifio E, Nagel AM, Weber M-A, et al. 3 Tesla MRI detects intracellular 23Na overload in patients with hyperkalemic periodic paralysis and permanent weakness. Radiology. 2012 doi: 10.1148/radiol.12110980. [in press] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LoVecchio F, Jacobson S. Approach to generalized weakness and peripheral neuromuscular disease. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1997;15:605–623. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70320-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedmann-Bette B, Bauer T, Kinscherf R, et al. Effects of strength training with eccentric overload on muscle adaptation in male athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:821–836. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soltanzadeh P, Friez MJ, Dunn D, et al. Clinical and genetic characterization of manifesting carriers of DMD mutations. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20:499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolla V, Litwack G. Transcriptional regulation of the human Na/K ATPase via the human mineralocorticoid receptor. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;204:35–40. doi: 10.1023/a:1007009700377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Estrada M, Liberona JL, Miranda M, et al. E. Aldosterone- and testosterone- mediated intracellular calcium response in skeletal muscle cell cultures. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;279:E132–E139. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.1.E132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakakibara H, Engel AG, Lambert EH. Duchenne dystrophy: ultrastructural localization of the acetylcholine receptor and intracellular microelectrode studies of neuromuscular transmission. Neurology. 1977;27:741–745. doi: 10.1212/wnl.27.8.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young M, Funder J. Mineralocorticoid action and sodium-hydrogen exchange: studies in experimental cardiac fibrosis. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3848–3851. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rafael-Fortney JA, Chimanji NS, Schill KE, et al. Early treatment with lisinopril and spironolactone preserves cardiac and skeletal muscle in Duchenne muscular dystrophy mice. Circulation. 2011;124:582–588. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.031716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pitt B, Bakris G, Ruilope LM, et al. EPHESUS Investigators. Serum potassium and clinical outcomes in the Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study (EPHESUS) Circulation. 2008;118:1643–1650. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.778811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savoia C, Touyz RM, Amiri F, et al. Selective mineralocorticoid receptor blocker eplerenone reduces resistance artery stiffness in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2008;51:432–439. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.103267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burton LA, McMurdo ME, Struthers AD. Mineralocorticoid antagonism: a novel way to treat sarcopenia and physical impairment in older people? Clin Endocrinol. 2011;75:725–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imanishi T, Ikejima H, Tsujioka H, et al. Addition of eplerenone to an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor effectively improves nitric oxide bioavailability. Hypertension. 2008;51:734–741. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.104299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otte C, Moritz S, Yassouridis A, et al. Blockade of the mineralocorticoid receptor in healthy men: effects on experimentally induced panic symptoms, stress hormones, and cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:232–238. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hlavacova N, Bakos J, Jezova D. Eplerenone, a selective mineralocorticoid receptor blocker, exerts anxiolytic effects accompanied by changes in stress hormone release. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:779–786. doi: 10.1177/0269881109106955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matono T, Koda M, Tokunaga S, et al. The effects of the selective mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist eplerenone on hepatic fibrosis induced by bile duct ligation in rat. Int J Mol Med. 2010;25:875–882. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gasparo M, Joss U, Ramjoué HP, et al. Three new epoxy-spirolactone derivatives: characterization in vivo and in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;240:650–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delyani JA, Rocha R, Cook CS, et al. Eplerenone: a selective aldosterone receptor antagonist (SARA) Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 2001;19:185–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2001.tb00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]