Abstract

The subgingival microbial ecology is complex, and little is known regarding its bacteria species composition in healthy Chinese individuals. This study aimed to identify the subgingival microbiota from 6 healthy Chinese subjects. Subgingival samples from 6 volunteers were collected, the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using broad-range bacterial primers, and clone libraries were constructed. For the initial 2,439 sequences analyzed, 383 species-level operational taxonomic units (SLOTUs) belonging to seven phyla were identified, estimated as 51% [95% confidence interval (CI) 44–55] of the SLOTUs in this ecosystem. Most (85%) of the bacterial sequences, falling into 228 types of species, corresponded to known and cultivated species. However, 146 (6%) sequences, comprising 104 phylotypes, had <97% similarity to prior database sequences. Ten bacterial genera were conserved among all 6 individuals, comprising 2,000 (82%) of the 2,439 clones analyzed. Ten species were noted in all of the 6 subjects, comprising 1,435 (58.8%) of the 2,439 clones. Streptococcus infantis was the species most frequently cloned. Furthermore, certain species which may participate in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease were present in the 6 subjects. Although the initial subgingival plaque community of each subject was unique in terms of diversity and composition, 10 common key species were found in the 6 Chinese individuals. These ten species of bacteria in the human subgingival plaque in the 6 healthy individuals may be key species which, to some extent, affect periodontal health. Destruction of these key species in subgingival bacteria may break the microbiota balance and may easily lead to over-breeding conditions resulting in pathogenic oral disease.

Keywords: subgingival plaque, microbiota, microbial diversity, small subunit rRNA genes, healthy individuals

Introduction

Molecular-based environmental surveys of bacteria have revealed a large degree of previously uncharacterized diversity (1,2). More recently, the use of culture-independent methods has played a key role in the discovery of previously unrecognized species in the oral cavity as well as in redefining the pathogenesis of major oral infections (2–4). The outcome of these studies indicates that major oral infections are polymicrobial (5,6). Using culture-independent molecular methods, nearly 500 bacterial strains have been recovered from the subgingival crevice, a particularly well-studied microbial niche (6). Other investigators have used similar techniques to determine the bacterial diversity of saliva, subgingival plaque and carious roots (7,8). Over half of the species detected have not yet been cultivated (6). Data from these studies have implicated specific species or phylotypes in a variety of diseases and oral infections (4,9–13), but still only limited information is available on species in subgingival plaque of healthy subjects. Moreover, to date, culture-independent studies describing the bacterial community of subgingival plaque in Chinese individuals are limited.

It is known that extensive differences in eating habits exist between Chinese and American individuals. These differences may play an important role in alterations in the colonization of oral bacterial species. Hence, understanding of the entire bacterial community of subgingival plaque may aid in the diagnosis and treatment of caries in Chinese people. Aas et al (6) analyzed the oral flora of 5 healthy subjects in the US using Sanger sequencing and concluded that over 50% of the oral bacteria could not be cultured. Kroes et al (14) studied the subgingival plaque of a 39-year-old Caucasian male with cultivation and phenotypic analysis, and found that a significant proportion of the resident subgingival bacterial flora remained poorly characterized and uncultured. Paster et al (15) analyzed 5 American healthy subgingival plaque samples and acquired a preliminary understanding of the composition of subgingival plaque. Recent investigations of the human subgingival microbiota based on 16S rRNA gene sequences indeed have shown that many of the present bacterial species are novel species or phylotypes. However, we currently do no have a comprehensive understanding of the subgingival microbiota of healthy Chinese adults, nor do we know whether pathogenic bacteria related to oral disease are present or, if there are, what those bacteria are. Hence, the aim of our study was to determine the detailed species diversity of the subgingival microbiota of healthy Chinese adults.

Materials and methods

Subjects and sample collection

Six subjects (4 female and 2 male, ranging in age from 25 to 35 years) were included in the study. Subjects were excluded from this study if they had received systemic periodontal treatment in the preceding year or had taken antibiotics within the previous 3 months or were pregnant or nursing. They had no clinical signs of oral mucosal disease, periodontal disease or caries and did not suffer from halitosis. Their periodontia was healthy, and all periodontal pockets were <3-mm deep with no redness or inflammation of the gums. Subjects who were free of systemic diseases and had 28 teeth in occlusion were subjected to clinical examinations. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. All participants provided written informed consent.

Saliva was isolated with sterile cotton rolls, after which supragingival plaque was obtained using a fresh sterile curette from four sites, usually distolingual, on the 1st or 2nd molars, and the samples were pooled. All samples were placed in a sterile plastic tube and stored at −80°C until use.

DNA extraction and amplification of 16S rRNA genes

DNA in the samples was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The 16S rRNA genes were amplified under standard conditions using a universal primer set. The primer pair spanned positions 7–1541 of the E. coli 16S rRNA gene (forward primer, 5′-GAG AGT TTG ATY MTG GCTCAG-3′; reverse primer, 5′-GAA GGA GGT GWT CCA RCC GCA-3′) (6). Each PCR mixture (50 μl) contained 100 ng of the extracted DNA as a template, 20 pmol of each primer, 0.25 μl Takara Ex Taq (5 U/μl), 5 μl 10X Ex Taq buffer and 4 μl dNTP mixture (2.5 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate). For PCR, the process consisted of an initial denaturation of the template DNA at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 20 cycles of denaturing at 94°C for 1 min, the annealing temperature (TA) for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min. The TA was decreased stepwise by 1°C every 2 cycles from 65°C in the first cycle to 56°C in the 20th cycle, and a final extension was carried out at 72°C for 5 min. The results of the PCR amplification were examined by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel. DNA was stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under short-wavelength UV light. All PCR products were purified by E.Z.N.A.® Gel Extraction kit (Omega Bio-Tek, USA).

Phylogenetic analysis

All sequences with the same size were aligned using Clustal X 1.83 and modified by Jalview2.07. Sequences with >97% identity are typically assigned to the same species, those with >95% identity are typically assigned to the same genus and those with >80% identity are typically assigned to the same phylum, although these distinctions are controversial (16). Therefore, the redundancy cutoff was set at 97%.

After redundancies were removed, the remaining sequences were assigned to the most closely related sequence using the Megablast function of GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/blast.cgi) and Ribosomal Database Project II (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu). They were clustered by phylogenetic groups in each library. Chimeric sequences were detected using the RDP Check-Chimera program (release 8.1) and Bellerophon (17). The phylogenetic trees were generated by using MEGA 4.0. The statistical strength of the Neighbor-Joining method was assessed by bootstrap resampling (1,000 replicates). The richness of total bacteria communities of the 6 healthy Chinese human subgingival plaque was estimated by rarefaction analysis. The total number of phylotypes that may be present in the sampled subgingival plaque and its associated confidence interval (CI) were calculated by using a non-parametric richness estimator, Chao1, as previously described (18). Double principle coordinate analysis (DPCoA) (19) was implemented to investigate the relationships between phylotype dissimilarities using DPCoA functions within the R statistical package (www.rproject.org) (19).

Nucleotide sequence accession number

The clone sequences reported in this study were deposited in the GenBank database (assigned GenBank accession numbers: FJ470405-FJ470520; FJ470595-FJ470618; FJ470658-FJ470725; FJ470788-FJ470842; FJ470910-FJ470947; FJ470976-FJ471006).

Results

Classification of the clones

Partial sequences of ∼500 bp were obtained for 2,439 16S rRNA clones in order to identify the predominant bacterial species present in the subgingival plaque of 6 healthy Chinese subjects. A markedly high diversity, 383 bacterial species representing seven bacterial phyla, was observed for the 2,439 clones analyzed. The overall bacterial profile had 160 (85%) cultivable species within known genera and 373 (15%) sequences from not-yet-cultivated phylotypes or species that are currently unrecognized. The term ‘phylotype’ is used for clusters of clone sequences that differed from known species by ∼45 bases (or 3%) and were at least 97% similar to members of their cluster. Approximately 9.8% of clones analyzed in each category of healthy subjects were novel phylotypes.

Distribution of the clones at the genus and species level

The subgingival plaque samples from the 6 subjects yielded sequences representing 49 genera. Ten genera were observed in all 6 subjects, comprising 2,000 (82%) of the 2,439 clones analyzed, including Streptococcus (23.8% of all clones), Neisseria (12.9%), Fusobacterium (9.9%), Haemophilus (7.5%), Veillonella (5.9%), Granulicatella (5.3%), Aggregatibacter (4.9%), Selenomonas (3.9%), Capnocytophaga (1.3%) and Derxia (0.9%). The ten most common species, accounted for 58.8% of all clones (2,439) (Table I). Five species (Haemophilus pittmaniae, Campylobacter gracilis, Streptococcus infantis, Streptococcus gordonii and Veillonella parvula), detected in all 6 subjects, accounted for 37% of the clones analyzed. By contrast, 25% of the individual species-level operational taxonomic units (SLOTUs) were found in single subjects only.

Table I.

Species represented by 16S rRNA gene sequences from supergingival plaque ≥4 in 6 healthy Chinese subjects.

| Phylum | Genus | Species name | Clones (n)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | Total (%) | |||

| Proteobacteria | Neisseria | Neisseria mucosa | 4 | 9 | 20 | 34 | 10 | 77 (3.16) | |

| Neisseria zoodegmatis | 11 | 9 | 34 | 28 | 82 (3.36) | ||||

| Haemophilus | Haemophilus pittmaniae | 1 | 56 | 35 | 24 | 25 | 37 | 178 (7.30) | |

| Campylobacter | Campylobacter gracilis | 15 | 10 | 12 | 9 | 16 | 8 | 70 (2.87) | |

| Fusobacteria | Fusobacterium | Fusobacterium canifelinum | 39 | 4 | 31 | 39 | 52 | 165 (6.77) | |

| Firmicutes | Streptococcus | Streptococcus infantis | 6 | 28 | 168 | 17 | 42 | 112 | 373 (15.29) |

| Streptococcus mitis | 4 | 18 | 31 | 19 | 61 | 133 (5.45) | |||

| Streptococcus gordonii | 10 | 43 | 33 | 15 | 61 | 23 | 185 (7.59) | ||

| Granulicatella | Granulicatella elegans | 5 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 44 | 75 (3.08) | ||

| Veillonella | Veillonella parvula | 4 | 12 | 5 | 17 | 16 | 43 | 97 (3.98) | |

| Subtotal (n) | 99 | 190 | 334 | 166 | 280 | 366 | 1,435 (58.84) | ||

The ten most common species accounted for 58.8% of all clones (2,439).

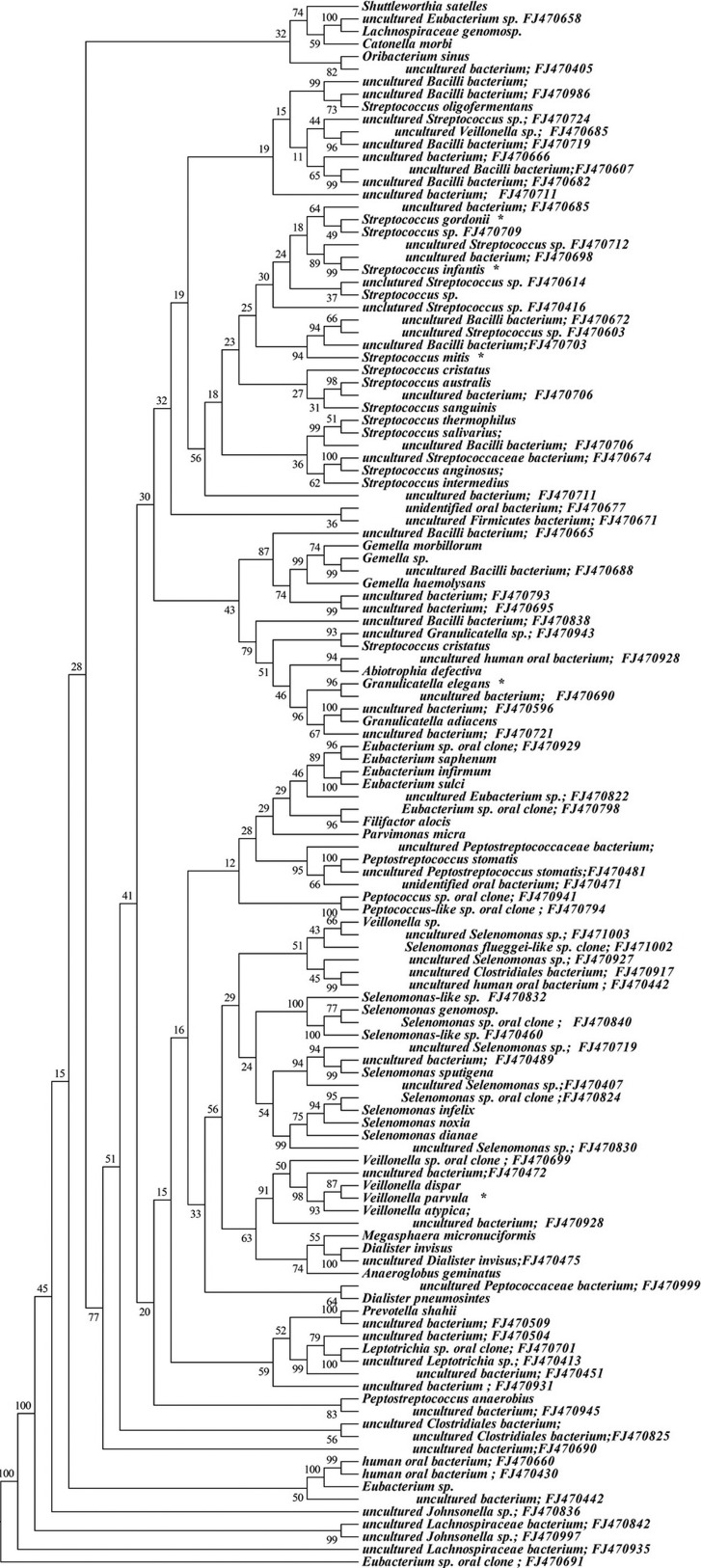

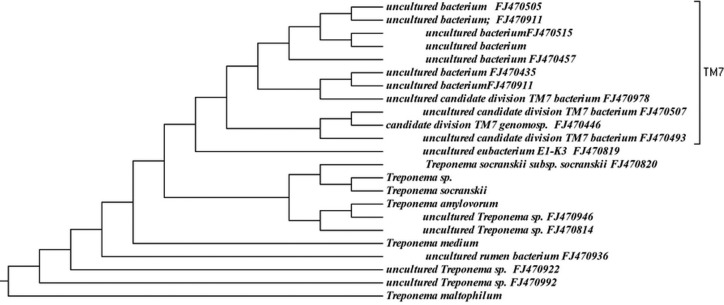

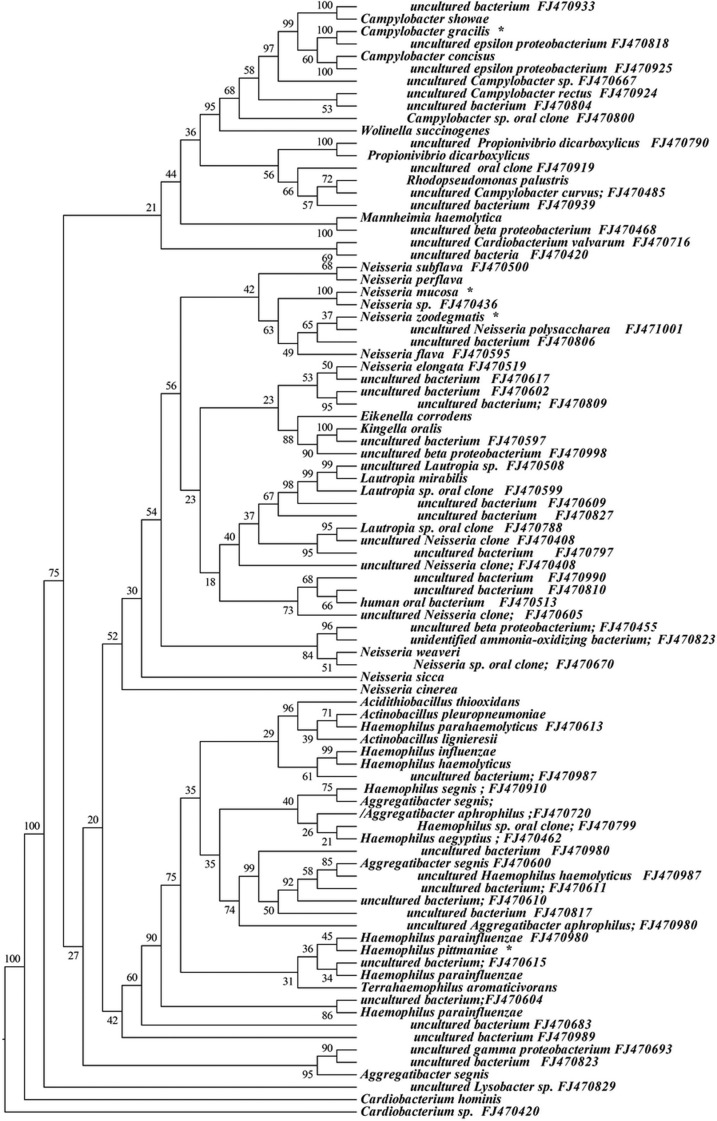

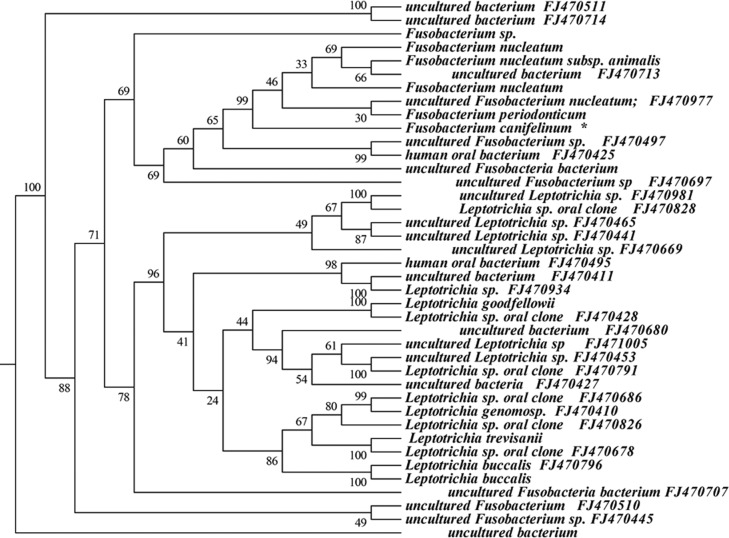

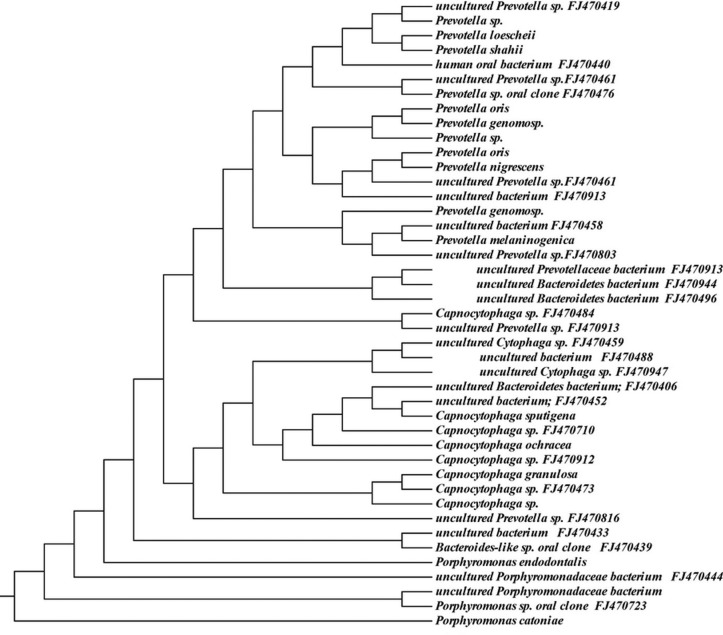

Detection of previously uncharacterized phylotypes

Approximately 6% (146 sequences) of the 16S rRNA gene sequences generated from the subgingival plaque did not match any known bacterial sequences present in public databases. In total, 104 previously uncharacterized phylotypes (146 clones) were detected, corresponding to seven bacterial phyla. The distribution of the known species and novel phylotypes within each of these phyla is shown in Figs. 1–6, where the phylogenetic diversity within each phylum is shown and discussed in detail below. The information presented includes bacterial species or phylotype, strain or clone identification and sequence accession number. The first letter of previously uncharacterized phylotypes is indented in each dendrogram.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic trees of the phyla Firmicutes identified from clone libraries. Novel phylotypes are defined as those taxa that are 97% similar in sequence comparisons to the phylotype’s closest relative. The first letter of novel phylotypes is indented in each dendrogram. *One of the ten most common species.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree of oral Treponemes and TM7 identified from clone libraries.

Species richness and diversity with Sanger sequencing

Estimations of species coverage, richness, evenness and diversity were calculated for the combined data set from the oral samples of the 6 subjects using conventional techniques and a corresponding sequence library.

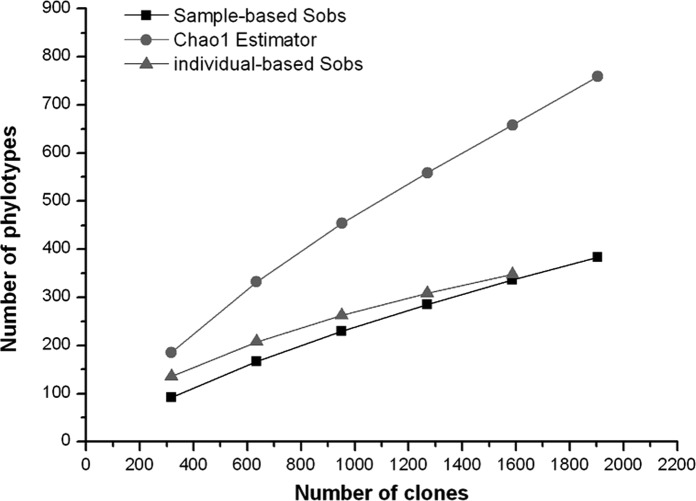

Good’s coverage was 90% for the overall sequence set, indicating that ten additional phylotypes would be expected for every 100 additional sequenced clones. This level of coverage indicated that the 16S rDNA sequences identified in these samples represent the majority of the bacterial species present in subgingival samples under study. Rarefaction curves were calculated for the overall combined data set using the individual-based Coleman method and the sample-based Mao Tau method (Fig. 7). The total number of SLOTUs present in the normal bacterial flora of subgingival samples in the 6 subjects was calculated using the Chao1 estimator, based on the distribution of singletons (18). We estimated that the bacterial biota from those specimens contains ∼759 SLOTUs (95% CI 637–939); the 383 SLOTUs observed represent 51% (95% CI 43.9–55.4) of the estimated species or phylotypes (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Observed collector curves and estimated SLOTU richness of subgingival bacterial flora in 6 healthy subjects. Each curve reflects the series of observed (Sobs) or estimated (Chao1) richness values obtained as the 2,439 16S rDNA clones were added to the data set in an arbitrary order. The rising slopes of the curves become less steep when an increasing proportion of phylotypes is encountered. Although 383 (95% CI 607–682) SLOTUs were observed, the Chao1 score of total species richness estimates that the normal bacterial flora of subgingival plaque in the 6 subjects contains ∼759 SLOTUs (95% CI 637–939). Based on this prediction, the present study identified 51% (95% CI 43.9–55.4) of the SLOTUs in subgingival microbial communities in the 6 subjects.

Discussion

Gross patterns of bacterial diversity have begun to emerge in recent years from comparative analyses of 16S rRNA gene sequences (6,20). In these surveys, 141 different bacterial taxa representing the bacterial flora of healthy American oral cavities have been reported (6). In our study, based on the analysis of 2,439 16S rRNA gene clones, the bacterial diversity of the microbiota from the subgingival plaque of 6 Chinese subjects was striking; a total of 383 different bacterial SLOTUs representing seven phyla, with approximately 90% species coverage was estimated. Hence, sequence-based environmental microbial surveys have demonstrated that cultivation methods under-represent the true extent of bacterial diversity.

In the present study, 32.2% of our sequences belonged to the genus Streptococcus, confirming the prevalence of Streptococcus species found in the healthy mouth by molecular methods (1). The most predominant bacterial genera in our study were Streptococcus, Neisseria, Granulicatella, Haemophilus, Fusobacterium, Aggregatibacter, Veillonella and Campylobacter, accounting for 70.7% of the total sequences. Furthermore, ten types of predominant bacteria were noted in the subgingival samples from the 6 healthy Chinese subjects (Table I). These ten species of bacteria were key species found in human subgingival plaque and, to some extent, affect periodontal health. The individual role of each species in a biological community is different; some species are critical and their existence affects the structure and function of the entire biological community; these species are called key species or key species groups (21). The role of dominant bacteria in subgingival microbiota can also be explained by the hypothesis regarding keystone species. Classification of key species in the medical field, mainly key types of biological pathogens, biological competition and biological mutualism is important. The key species are responsible for the maintenance of the ecosystem functions (21). Destruction of key bacterial species in subgingival plaque may disrupt the microbiota balance and can easily lead to over-breeding conditions resulting in pathogenic oral disease.

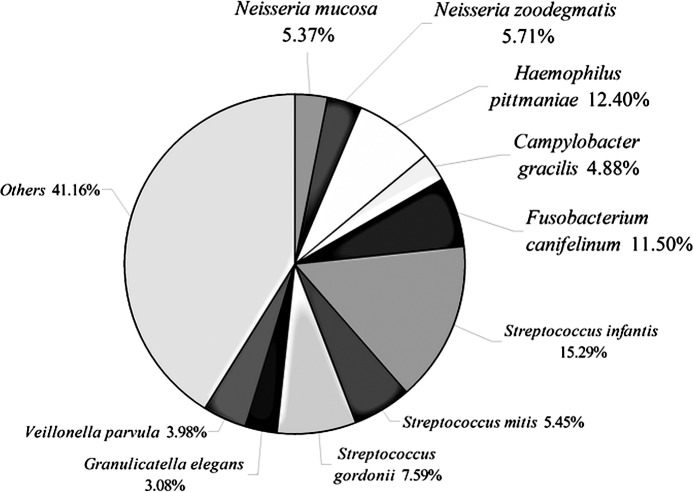

In a recent molecular study, the most predominant bacterial species found in the subgingival plaque were Streptococcus spp., Fusobacterium, Leptotrichia buccalis, Corynebacterium matruchotii, S. oralis and S. mitis (6). We also identified the ten most common species that accounted for 58.8% of all clones. These ten species included Neisseria mucosa, Neisseria zoodegmatis, Haemophilus pittmaniae, Campylobacter gracilis, Fusobacterium canifelinum, Streptococcus infantis, Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus gordonii, Granulicatella elegans and Veillonella parvula (Fig. 8). This discrepancy in results may be due to the three following reasons. The number of subjects in this study was relatively small, and inter-individual differences associated with gender, age or eating habits may become apparent when larger numbers of subjects are studied. Moreover, there was a deeper sequencing effort per individual in the present study (average 57.5 clones per subject in the Aas et al study for a total of 2,589 clones, in contrast to an average of 500 clones per individual in this study). In addition, different DNA extraction methods and different broad-range PCR primers may also explain the divergent results.

Figure 8.

Community profile of the ten dominant members from supergingival plaque of 6 healthy Chinese subjects.

Among the predominant species, Streptococcus infantis was most frequently cloned. This species is commonly found in the mouth of infants (22), which does not match the results of our experiment. Streptococcus infantis may be characteristic of the subgingival microflora of the 6 Chinese subjects. In addition, the predominant species Campylobacter gracilis, Campylobacter showae, Kingella oralis and Neisseria mucosa noted in the previous experiment were also noted in healthy American subjects (15). The pathogens that are known to have a close link to periodontitis, such as Porphyromonas endodontalis, Capnocytophaga granulosa and Prevotella melaninogenica (15,23), were respectively detected in our experiment in one clone in 1 healthy subject. This suggests that the oral cavity of a healthy individual is not necessarily pathogen-free; the absence of symptoms of oral disease does not indicate the absence of pathogens in the oral cavity. In conclusion, these reports suggest that, in the subgingival microbiota of Chinese individuals, there are pathogen and symbiotic bacteria competing against each other eventually achieving a balance for a healthy oral environment.

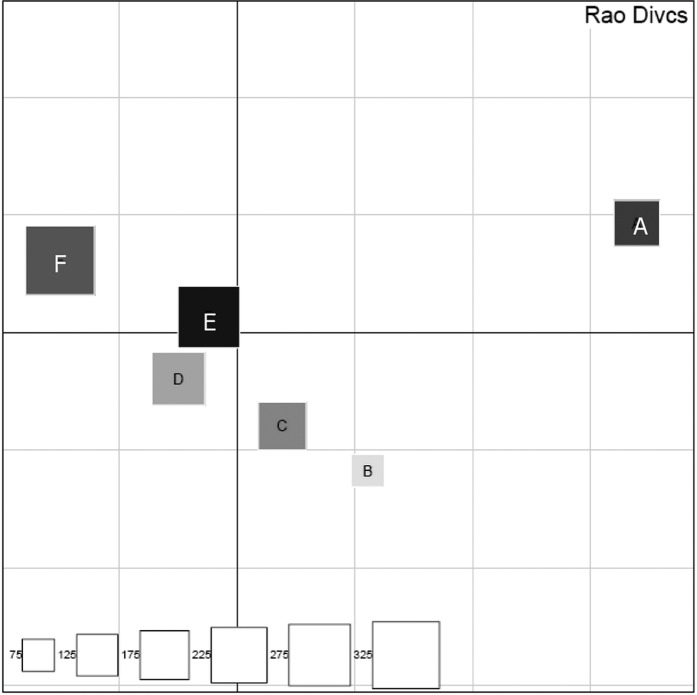

Our results revealed that each individual had a certain difference in the subgingival microbiota (Fig. 9). Differences in subgingival microbiota among individuals are caused by various physical and chemical characteristics of the oral environment, such as temperature, oxygen tension and availability of nutrients (24). Most oral bacteria are grown in a neutral environment (pH equal to 7). The oral cavity provides a relatively constant pH environment,which provides a suitable foundation for the colonization of bacteria. A variety of exogenous food, the saliva buffer system and bacterial fermentation may alter the pH of the oral environment, resulting in different bacterial colonization in individuals (25). However, the factors affecting bacterial diversity may include ethnicity, geographic region, different eating habits, oral hygiene habits and gender. In addition, this study only preliminarily analyzed 6 samples of healthy subgingival plaque. To better represent the characteristics of the healthy subgingival microbiota, study of a large number of samples is required. In addition, how the differences in subgingival microbiota fluctuates over time warrants further analysis.

Figure 9.

DPCoA of SLOTU relatedness in samples obtained from 6 subjects. Subjects are indicated by A–F. In a representation of the first two orthogonal principal axes, based on a sample dissimilarity matrix, samples from subjects A–F are plotted by using different shades of grey, with square size proportional to the sample’s Rao diversity index. The scale (bottom left) indicates the relative diversity of squares, with the test sample of smallest diversity indexed as 1.0.

As determined in previous studies using culture-independent molecular techniques, over 60% of the bacterial flora identified was represented by not-yet-cultivated phylotypes (6,15). In the present study, we detected 104 of 383 SLOTUs (27.2%) as not-yet-cultivable phylotypes with Sanger sequencing. One hundred and four unknown phylotypes may be new species of a known genus or unknown species of a yet unkown genus. There were 104 phylotypes noted in the subgingival microbiota of the 6 healthy subjects; 92 had only one clone for each. A portion of the ‘new species’ was crossing bacteria (also known as foreign bacteria) rather than normal microbiota (also known as permanent microbiota), relative to the permanent microbiota found in the oral cavity. The crossing bacteria may be non-pathogenic or opportunistic pathogens for which the residence time is short and colonization is caused by adverse effects, while normal microbiota are relatively fixed and regularly settled in a specific location and are an integral part of the host. Although a ‘new phylotype’ in a sense can be understood as a new species, the physiological characteristics of new species and their relationship with diseases is not yet clear at present, and this has brought certain difficulties in the study of their role in the ecological environment. Understanding the nature of the study of new species is very difficult. The main reason for this is that current technology cannot meet the conditions of culture.

In conclusion, in comparing the results reported in the literature (3,14,15), we found that there was an overlap in the species detected in the subjects without symptomatic periodontal disease and periodontitis. Thus, certain key species may be critical for the maintenance of ecosystem stability and oral health, or may be occasional pathogens. Hence, pathogens and symbionts are in dynamic equilibrium, and maintainence or disruption of this equilibrium may affect oral health or result in disease.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the phylum Proteobacteria identified from clone libraries.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree of the phyla Fusobacteria identified from clone libraries.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of the phylum Bacteroidetes identified from clone libraries.

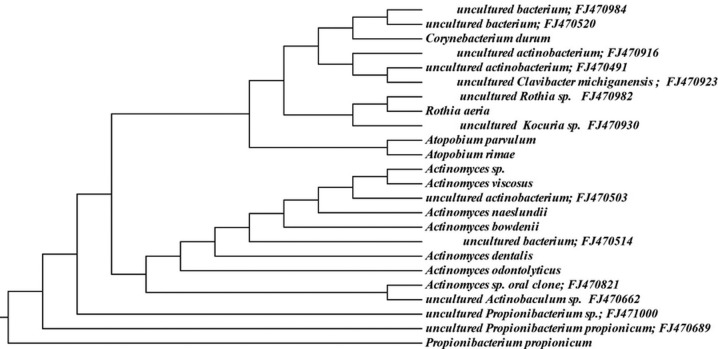

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree of the phyla Actinobacteria identified from clone libraries.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Shanghai Education Commission Project [project no. (2010)83] and the Shanghai Leading Academic Discipline Project (project no. T0202).

References

- 1.Bik EM, Long CD, Armitage GC, et al. Bacterial diversity in the oral cavity of 10 healthy individuals. ISME J. 2010;4:962–974. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Preza D, Olsen I, Willumsen T, Grinde B, Paster BJ. Diversity and site-specificity of the oral microflora in the elderly. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:1033–1040. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0743-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colombo AP, Boches SK, Cotton SL, et al. Comparisons of subgingival microbial profiles of refractory periodontitis, severe periodontitis, and periodontal health using the human oral microbe identification microarray. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1421–1432. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corby PM, Lyons-Weiler J, Bretz WA, et al. Microbial risk indicators of early childhood caries. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5753–5759. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5753-5759.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riggio MP, Lennon A, Rolph HJ, et al. Molecular identification of bacteria on the tongue dorsum of subjects with and without halitosis. Oral Dis. 2008;14:251–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2007.01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aas JA, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, Olsen I, Dewhirst FE. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5721–5732. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5721-5732.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aas JA, Griffen AL, Dardis SR, et al. Bacteria of dental caries in primary and permanent teeth in children and young adults. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1407–1417. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01410-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanner AC, Kent R, Jr, Kanasi E, et al. Clinical characteristics and microbiota of progressing slight chronic periodontitis in adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:917–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakamoto M, Rocas IN, Siqueira JF, Jr, Benno Y. Molecular analysis of bacteria in asymptomatic and symptomatic endodontic infections. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2006;21:112–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2006.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanner AC, Paster BJ, Lu SC, et al. Subgingival and tongue microbiota during early periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2006;85:318–323. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munson MA, Banerjee A, Watson TF, Wade WG. Molecular analysis of the microflora associated with dental caries. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3023–3029. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.7.3023-3029.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakamoto M, Huang Y, Umeda M, Ishikawa I, Benno Y. Detection of novel oral phylotypes associated with periodontitis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;217:65–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker MR, Paster BJ, Leys EJ, et al. Molecular analysis of bacterial species associated with childhood caries. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1001–1009. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.3.1001-1009.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroes I, Lepp PW, Relman DA. Bacterial diversity within the human subgingival crevice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14547–14552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paster BJ, Boches SK, Galvin JL, et al. Bacterial diversity in human subgingival plaque. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3770–3783. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.12.3770-3783.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schloss PD, Handelsman J. Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:1501–1506. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1501-1506.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huber T, Faulkner G, Hugenholtz P. Bellerophon: a program to detect chimeric sequences in multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2317–2319. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes JB, Hellmann JJ, Ricketts TH, Bohannan BJ. Counting the uncountable: statistical approaches to estimating microbial diversity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:4399–4406. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.10.4399-4406.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pavoine S, Dufour AB, Chessel D. From dissimilarities among species to dissimilarities among communities: a double principal coordinate analysis. J Theor Biol. 2004;228:523–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao Z, Tseng CH, Pei Z, Blaser MJ. Molecular analysis of human forearm superficial skin bacterial biota. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2927–2932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607077104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearce DA, van der Gast CJ, Woodward K, Newsham KK. Significant changes in the bacterioplankton community structure of a maritime Antarctic freshwater lake following nutrient enrichment. Microbiology. 2005;151:3237–3248. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bin-Nun A, Bromiker R, Wilschanski M, et al. Oral probiotics prevent necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight neonates. J Pediatr. 2005;147:192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayanagi G, Sato T, Shimauchi H, Takahashi N. Detection frequency of periodontitis-associated bacteria by polymerase chain reaction in subgingival and supragingival plaque of periodontitis and healthy subjects. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2004;19:379–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.2004.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lodhia P, Yaegaki K, Khakbaznejad A, et al. Effect of green tea on volatile sulfur compounds in mouth air. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 2008;54:89–94. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.54.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duckworth RM. The science behind caries prevention. Int Dent J. 1993;43:529–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]