Abstract

Background:

Patients with head injury continue to improve over time and a minimum follow-up of six months is considered necessary to evaluate outcome. However, this may be difficult to assess due to lack of follow-up. It is also well known that operated patients who return for cranioplasty usually have the best outcome.

Aims and Objectives:

To assess the outcome following severe head injury using cranioplasty as a surrogate marker for good outcome.

Materials and Methods:

This was a retrospective study carried out from January 2009 to December 2010. All patients with severe head injury who underwent decompressive craniectomy (DC) in the study period were included. Patients who came back for cranioplasty in the same period were also included. Case records, imaging and follow up visit data from all patients were reviewed. Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) on admission and Glasgow Outcome Score (GOS) at discharge were assessed.

Observations and Results:

Of the 273 patients, 84.25% (n=230) were males and 15.75% (n= 43) were females. The mean age was 34.3 years (range 2-81 years, SD 16.817). The mean GCS on admission was 5.615 (range 3-8, SD 1.438). The in-hospital mortality was 54% (n=149). Good outcome (GOS of 4 or 5) at discharge was attained in 22% (n=60) patients. Sixty five patients returned for cranioplasty (with a GOS of 4 or 5) during the study period. There was no statistical difference in the number of patients discharged with good outcome and those coming back for cranioplasty in the study period (P>0.5). Patients who came back for cranioplasty were younger in age (mean age 28.815 years SD 13.396) with better admission GCS prior to DC (mean GCS 6.32 SD1.39).

Conclusions:

In operated severe head injury patients significant number of patients (24% in our study) have excellent outcome. However, insignificant number of patients had further improvement to GOS 4 or 5 (good outcome) from the time of initial discharge. This suggests that due to lack of intensive rehabilitative facilities, GOS at discharge may be representative of final outcome in the vast majority of cases of severe head injury in developing countries like India

Keywords: Cranioplasty, outcome, rehabilitation, severe head injury

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic brain injury is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide. Every year, about 1.5 million affected people die and several millions receive emergency treatment.[1,2] Most of the burden (90%) is in low and middle-income countries.[3] The incidence varies from 67 to 317 per 10,000 in different continents and the mortality rates are in the range of near 1% for minor injury and 48% for severe head injury. It is the main cause of death and disability in people under 40 years of age.[4] The glasgow coma scale (GCS) at the time of admission is the single most important predictor of outcome. Patients with head injury continue to improve over time and a minimum follow-up of six months is considered necessary to evaluate the outcome. However, this may be difficult to assess due to lack of follow-up, especially in developing countries like India.

On the other hand, a subset of patients who had decompressive craniectomy will return for cranioplasty several months following the injury. These patients usually have a glasgow outcome score (GOS) of 4 or 5 and most have reintegrated into society. Cranioplasty at this point in time is performed only for esthetic reasons. The aim of this study was to see whether there was a significant difference between the number of patients with good outcome at the time of discharge following decompressive craniectomy and those patients coming after prolonged follow-up.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective study carried out from January 2009 to December 2009 (12 months) at the JPN Apex Trauma Center, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. All patients with severe head injury with a GCS 8 or less who underwent decompressive craniectomy (DC) in the study period were included. Patients who came back for cranioplasty in the same period were also included in the study. As the study period was constant, not necessarily the same patients who underwent decompressive craniectomy would come back for cranioplasty during the study. However, as the number of decompressive craniectomies done is relatively constant every month, it is assumed that cranioplasty done within the study period would be representative of the group. Case records, imaging and follow-up visit data from all patients were reviewed. GCS on admission was assessed. Outcome at discharge was defined with the GOS. The scale comprises five categories: death, vegetative state, severe disability, moderate disability, and good recovery. For the purpose of this analysis, we dichotomised outcomes into favourable (Grade IV and V) and unfavourable (Grade 1-III).[5]

Category and definition on glasgow outcome scale

Grade V: Good recovery: able to return to work or school

Grade IV: Moderate disability: able to live independently; unable to return to work or school

Grade III: Severe disability: able to follow commands/unable to live independently

Grade II: Persistent vegetative state: unable to interact with environment; unresponsive

Grade I: Dead

Patients were given a date for cranioplasty ranging 3-6 months from discharge. On re-admission patients were revaluated and the GCS calculated.

Those patients who underwent surgeries for other indications such as depressed fracture elevation and epidural hematoma evacuation were excluded from the study cohort. The data was analysed using Student's t test, Chi-square test and the Wilcoxon ranksum tests.

RESULTS

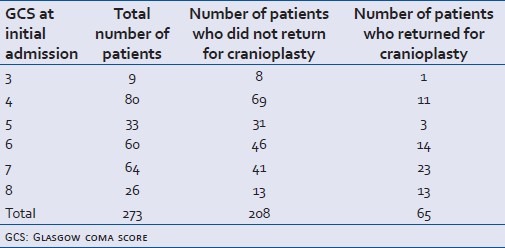

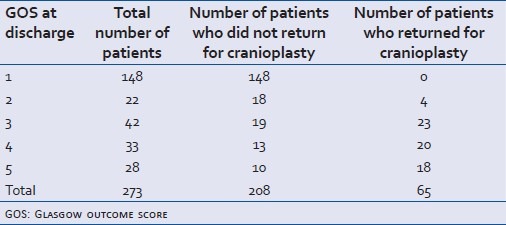

A total of 273 decompressive craniectomies were done during the study period with a mean of 21.75 every month (range 19-24). Out of that, 84.25% (n=230) were male and 15.75% (n=43) were female. The mean age was 34.3 years (range 2-81 years, SD 16.817). The mean GCS on admission was 5.615 (range 3-8, SD 1.438) [Table 1]. The in-hospital mortality (GOS 1) was 54% (n=149). Favourable outcome (GOS of 4 or 5) at discharge was attained in 22% (n=61) patients [Table 2].

Table 1.

Admission GCS (at the time of initial decompressive craniectomy) of patients in ‘cranioplasty’ and ‘no Cranioplasty’ groups

Table 2.

Glasgow outcome score (at the time of discharge following decompressive craniectomy) of patients in ‘cranioplasty’ and ‘no cranioplasty’ groups

During the study period, 65 patients returned for cranioplasty. The M:F ratio (6.2:1) matched with the study cohort. The age and presenting GCS of these two groups were compared using an independent sample 2-tailed t test and the Mann-Whitney U test, respectively.

There was no statistical difference in the number of patients discharged with good outcome and those coming back for cranioplasty in the study period (P>0.5). Patients who came back for cranioplasty were found to be younger (mean age 28.82, years SD 13.37) with better admission GCS prior to DC (mean GCS 6.32, SD1.39)

DISCUSSION

Most studies measure outcome at six months or later in patients with severe head injury. This is due to the fact that patients may continue to improve with time and outcome assessment after prolonged follow up is more representative of the final outcome. Long term outcome of operated severe head injury patients in developing countries cannot be assessed due to the lack of follow up. This study examined whether GOS at discharge could be representative of final outcome in severe head injured patients and found that contrary to perception, there is no significant change in the number of patients improving to good outcome (GOS 4 and 5) from the time of initial discharge following severe head injury. Although the reasons are not clear, lack of proper rehabilitative facilities may be a factor for this finding. In our hospital too, patients are discharged to home-based physiotherapy and rehabilitation, which is usually done by the relatives and negligible rehabilitative inputs are available to most patients. This is a very worrying finding as it shows that in spite of marked improvement in acute care there is a huge potential in improving outcomes in patients with severe head injuries in developing countries like India and a major thrust is required for building rehabilitative facilities in our country.

Another cause for worry was the high mortality rate (54%) in this study. One of the reasons could be the delayed arrival of patients from far distances resulting in worse outcomes. However, the factors were not analysed in this study. For the year 2010, our overall mortality in severe head injury is 29.9% (unpublished data). This includes both operated and conservatively managed patients.

On the flip side, our study shows that significant number of patients undergoing decompressive craniectomy for severe head injury have excellent outcomes. Lemcke, Ahmadi and Meier in their study had 48% mortality during the hospital stay and 21% were discharged in a vegetative state (GOS 2). Among them, 24% were discharged with severe disability, while 7% had moderate disability at discharge.[6]

Older age, poor GCS, absent pupil reactivity, and the presence of major extracranial injury predict poor prognosis. All of these variables have been previously identified as prognostic factors for poor outcome in traumatic brain injury.[7] In our study too, GCS showed a clear linear relation with mortality. Also, increasing age was associated with worse outcome, and this finding too was similar to previous studies.[8,9] Plausible explanations for this include extracranial comorbidities, changes in brain plasticity, or differences in clinical management associated with increasing age.[4]

CONCLUSION

In operated severe head injury, significant number of patients (24% in our study) have excellent outcome. However, insignificant number of patients had further improvement to GOS 4 or 5 (good outcome) from the time of initial discharge. This suggests that due to lack of intensive rehabilitative facilities, GOS at discharge may be representative of final outcome in the vast majority of cases of severe head injury in developing countries like India.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bruns J, Jr, Hauser WA. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: A review. Epilepsia. 2003;44(suppl 10):2–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.44.s10.3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleminger S, Ponsford J. Long term outcome after traumatic brain injury. BMJ. 2005;331:1419–20. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7530.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofman K, Primack A, Keusch G, Hrynkow S. Addressing the growing burden of trauma and injury in low- and middle-income countries. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:13–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.039354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basso A, Previglino I, Durate JM, Ferrari N. Advances in management of Neurological trauma in different continents. World J Surg. 2001;25:1174–8. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet. 1975;1:480–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92830-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemcke J, Ahmadi S, Meier U. Outcome of patients with severe head injury after decompressive craniectomy. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2010;106:231–3. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-98811-4_43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Brain Trauma Foundation. The American Association of Neurological Surgeons. The Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care. Age. J Neurotrauma. 2000;17:573–81. doi: 10.1089/neu.2000.17.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hukkelhoven CW, Steyerberg EW, Rampen AJ, Farace E, Habbema JD, Marshall AF, et al. Patient age and outcome following severe traumatic brain injury: An analysis of 5600 patients. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:666–73. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.4.0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Signorini DF, Andrews PJ, Jones PA, Wardlaw JM, Miller JD. Predicting survival using simple clinical variables: Acase study in traumatic brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:20–5. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]