Abstract

Objective:

The study aimed to compare the effect of liothyronine and piracetam on three subscales of the Wechsler memory test on patients under treatment with ECT.

Materials and Methods:

In a double blind clinical trial, 60 of 99 patients between 20 and 45 years old, under treatment with ECT were studied in three groups. Patients in the allocation groups received liothyronine, piracetam, or placebo, from the first session of ECT until 1 month after the last session of ECT. Personal information, orientation, and mental control were tested in the participants at first, fourth, and last session of ECT and 1 month after the last session of ECT. Data were analyzed with Repeated measure ANOVA using SPSS 13.

Results:

There wasn’t any significant difference among three groups in demographic characteristics before the study and number of ECT sessions (P=0.684). After intervention, a significant difference in memory scores was seen in third and fourth assessment sessions (0.002). Orientation subscales showed a significant difference among four assessment sessions (P=0.001). Personal information and mental control never decreased in the liothyronine group. There was no significant difference among three studied groups in personal information, orientation, and mental control (P>0.05).

Conclusion:

Memory changes due to ECT may be limited to some parts of memory like orientation. More powerful studies for comparison between the effect of liothyronine and placebo are necessary.

Keywords: Electroconvulsive therapy liothyronine, memory impairment, piracetam

INTRODUCTION

Camphor-induced convulsion was used as a treatment for psychosis in the 16th century. In 1934, Von Maddona reported that he has successfully treated catatonia and other symptoms of schizophrenia with drug-induced convulsion.

Based on Von Maddona's works, Cerletti and Bini used electrical convulsion as a treatment modality for the first time in 1938. At first, this treatment was known as electroshock therapy or EST, but then its name changed into electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Nowadays, thousands episodes of ECT are done annually, all over the world.[1]

The most common therapeutic use of ECT is the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD).[2] ECT is used for the treatment of manic episodes, schizophrenia, catatonia, periodic psychosis, atypical psychosis, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), delirium, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome, too.[1,2] One of the important complications of ECT is memory impairment. Although 75% of the patients mentioned memory impairment as the worst complication of ECT, but nearly all of the patients go back to their basic cognitive level after 6 months. Yet some of the patients complained about permanent memory problems.[1,2]

Many researchers have studied the prophylactic effect of Physostigmine,[3] Naloxan,[4] Dexamethasone,[5] and Piracetam[6,7] on the memory defect associated to ECT.

Karahmadi et al. study showed useful effect of piracetam on prevention from ECT-induced amnesia.[8] In contrast, some of the studies didn′t report significant effect of piracetam on memory scores.[9,10] Some researchers showed positive effect of thyroid hormones on decreasing the cognitive side effects of ECT.[11,12] Mousavi et al. showed that liothyronine can be effective in prevention from ECT-induced amnesia.[13] These different results may be because of the difference in measurement tools, type of intervention, or unsatisfactory conditions of patients who are candidate for ECT.

Due to these controversial results and because we didn’t find any comparative study between different methods of studies of ECT-associated amnesia, this study was designed to compare the efficacy of piracetm and liothyronine on prevention from ECT-induced amnesia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a double blind randomized clinical trial that both psychologist (who assessed the memory) and the patients were blind to the kind of used medications. Ninty-nine patients with MDD, bipolar disorder (BD), and schizophrenia who were candidate for ECT by psychiatrist and were referred to ECT center in Noor Hospital (Isfahan, Iran) during 11 months were selected. Inclusion criteria were: patients with MDD, BD, or schizophrenia, age between 20 and 45 years, informed consent for participation, prescription of at least four-ECT session treatment, no mental retardation, dementia or thyroid function impairment (based on history, physical exam, and the patients’ hospital file. Exclusion criteria were delirium due to ECT.

The treatment protocol was explained to the patients and written consents were obtained from the patients or their first degree relatives (for patients who couldn’t decide due to their conditions). All 99 patients with inclusion criteria were randomly allocated in three groups: liothyronine, piracetam, and placebo. Ten participants in the liothyronine group, 14 in piracetam group, and 15 in placebo group discontinued ECT before four sessions. Consequently, 20 patients remained in each group.

Patients in the liothyronine group received two tablets (each tablet: 25΅g) daily, in the piracetam group, two tablets (each tablet: 800 mg) daily, and, in the placebo group 2 placebo tablets bid, since 1 day before the first ECT session till 1 month after the last ECT session.

The ECT procedure was done routinely (i.e. 3 days each week, every other day), with bitemporal electrode placement, 1 ms pulse width, voltage 220 V., 0.9 A. current, frequency 30-70 Hz, one seizure per session, and using the Thynatron system. The anesthesia was inducted by sodium thiopental 2-3 mg/kg. We didn’t discontinue psychiatrist advised drugs for patients simultaneously (like neuroleptics or stat benzodiazepines for controlling occasional agitation of patients), but none of them received any anticonvulsants or lithium carbonate during the study.

Wechsler Memory Scale-R (WMS-R) was used for the assessment of memory function in the participants. This is the most common memory assessment tools in adults and consists of seven subscales including personal and current information, orientation, mental control, logical memory, digit span, visual memory, associative learning and paragraph preserving.[14] This scale can assess learning, immediate learning, concentration, attention, and remembering long-term information. Psychometric assessment of Iranian version of Wechsler memory scale showed retest coefficients ranged from 0.28 to 0.98 for subscales and forms, which is satisfactory. It s validity was confirmed by testing on patients with memory defect compared with healthy subjects.[15]

Because of moral issues and participants limited patience and concentration, only first three subscales of the Wechsler memory scale, i.e. personal information (6 scores), orientation (5 scores), and mental control (9 scores) were used.

The Wechsler memory scale was performed for all the participants by an experienced psychologist before the first session of ECT, before the fourth session, before the last session and one month after the last session of ECT. The total score of three subscales was calculated and reported by the psychologist. Drug side effects were gathered and reported via a check list that was designed for this purpose.

Data were analyzed with Repeated Measure of ANOVA using SPSS13.

RESULTS

Sixty participants were enrolled in this double blind randomised controlled trial. Their age ranged from 18 to 45 year with Mean (SD) of 32.1 (7.5) year. From them, 30 (50%) were male: 40 (66.7%) were married and 52 (86.7%) were college level or less.

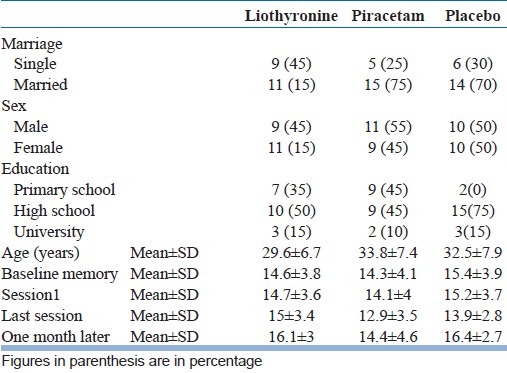

Table 1 summarizes some demographic characteristics of the participants before intervention based on their allocation to one of the liothyronine, piracetam, or placebo group. There wasn’t any significant difference among three groups in terms of age, sex, education level, and marital status (P value>0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the patients and mean scores of memory at each stages of evaluation based on Wechsler Memory Scale

There wasn’t any significant difference among three groups in memory scores before ECT (P value=0.684) and this result shows similar distribution of the patients in three groups according to memory scores at the beginning of the study [Table 1].

There was no significant difference in the numbers of ECT sessions among three groups (M±SD in group A=8.70±2.07, in group B=8.20±1.09, and in group C=8.05±1.66, P<0.05). No serious drug side effects that can lead to discontinuing of the medications were seen in the participants and no post ECT delirium was reported.

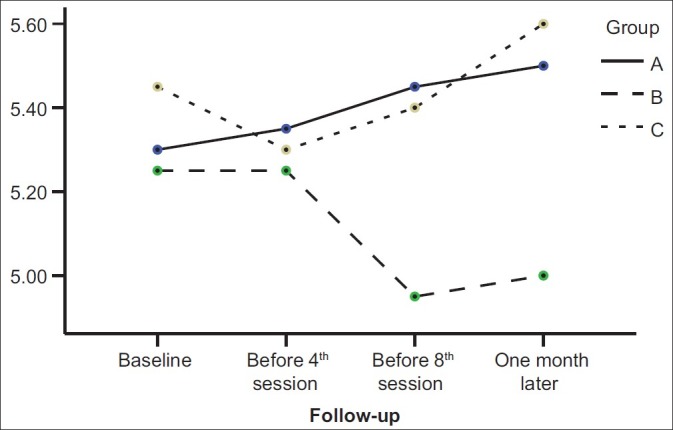

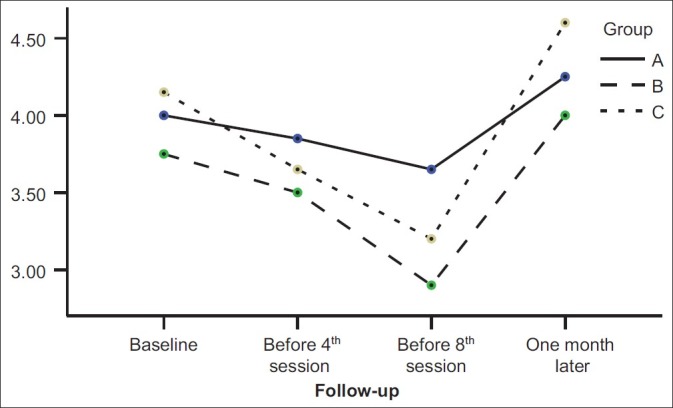

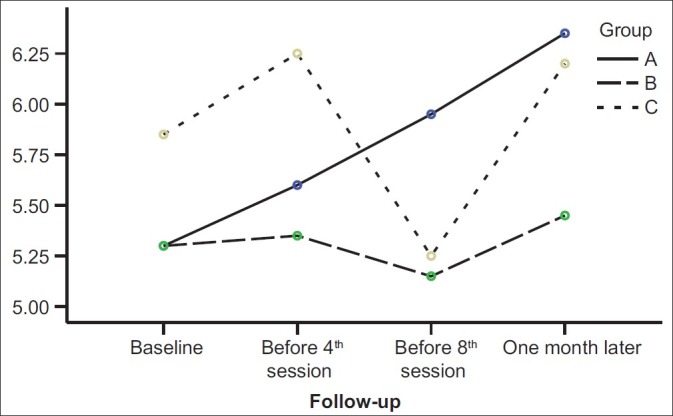

As Figure 1 shows, the personal information scores in the piracetam group after a mild decrease (before the fourth ECT session) were increased, but in the liothyronine group, scores were increased continuously from the beginning to the end of intervention. The Orientation scores were decreased in all three groups until the third assessment session (at the end of ECT sessions) and then significantly began to increase in three groups (P value<0.001) [Figure 2]. The mental control scores in the liothyronine group were increased continuously but in two other groups such result was not reported [Figure 3]. Because there weren’t any significant differences among the demographic properties of the participants, and because the simple size of groups weren’t adequately large, the analysis performed without covariates such as: age, gender, marriage status, and educational level [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Comparison among personal information scores in three studied groups during four memory assessment sessions. (A: liothyronin, B: piracetam, C: placebo)

Figure 2.

Comparison among scores of orientation subscale in three studied groups during four memory assessment sessions. (A: liothyronin, B: piracetam, C: placebo)

Figure 3.

Comparison among scores of mental control subscale in three studied groups during four memory assessment sessions. (A: liothyronin, B: piracetam, C: placebo)

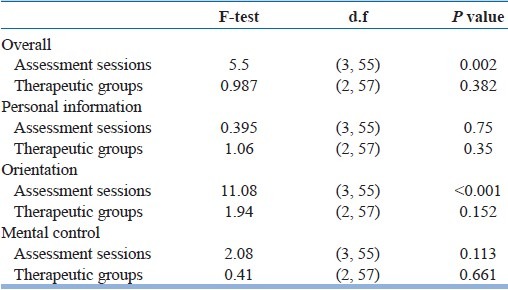

In comparison of sessions with each other, a significant difference in memory scores was seen between third and fourth session (P value=0.002) but a comparison among all four assessment sessions showed only a significant difference in orientation scores [Table 2].

Table 2.

Results of repeated measure of anova for scores of memory in three studied groups of liothyronine, piracetam, and placebo based on “overall” and “three separated subscales (personal information, orientation and mental control)”

In this study, during four assessment sessions we compared scores of each of the three subscales (personal information, orientation, and mental control) separately among three groups and then compared all of them together among three groups. Repeated measure of the ANOVA test showed no significant difference in personal information, orientation, and mental control in three studied groups [Table 2].

DISCUSSION

A comparison among four assessment sessions in our study showed a significant decrease in orientation score by the end of third assessment session (P value=0.001) and then significant improvement in it during 1 month after the last session of ECT (P value=0.001). Scores of two other subscales (information and mental control) didn’t show significant differences in assessment sessions. These findings may explain the controversies among previous studies which showed good efficacy of piracetam[6–8] or didn’t find any efficacy of piracetam on preventing memory impairment.[9,10] It means that ECT have different effects on different aspects of memory. For example, ECT may have a more negative effect on orientation [Figure 2 and Table 2] but has no important effect on some other aspects of the memory [Table 2] or, may affect them only under special conditions like underlying diseases, medications, and age.

Our findings showed that although there wasn’t any significant difference in personal information scores among three studied groups (P=0.35) and four assessment sessions (P=0.75) [Table 2], but information scores in liothyronine groups were never decreased [Figure 1]. These findings are close to the results of Stern et al. study,[11] Stern and Tremont study,[12] and Mousavi and Navvab study.[13] All of these results suggest that although different previous interventions don’t have similar effects on prevention from memory impairment, but evidences like this study findings [Figure 1 and 3] and some previous studies[11–13] show that liothyrinine can prevent from some ECT-induced memory impairment, whereas placebo and piracetam don’t have this significant effect. In fact, this study by separating assessment of different aspects of memory and comparing the efficacy of different interventions on them help to clarify some controversies.

Our study had some limitations that make it difficult to generalize the results for all of the conditions. Some of our participants received some kind of medications along with ECT that we couldn’t discontinue because of moral issues and their therapist’ prescription. These medications (like neuroleptic different doses) may have interfered with our results. The second limitation of this study was using only three subscales of the Wechsler memory test because of low tolerance of our patients. Further studies using the other parts of the Wechsler memory test are necessary for more accurate results.

Our study conclusion is that ECT doesn’t have similar effects on all aspects of WMS-R, for example the orientation subscale assessment shows more impairment than other subscales [Figure 2]. Although our results didn’t show any significant difference between liothyronine and piracetam on prevention from ECT-induced memory impairment, but there were some evidences which showed liothyronine is more useful for prevention from ECT-induced memory impairment, and this action begins since the onset of liothyronine use [Figures 1 and 3].

More powerful studies, especially on all aspects of memory, are necessary for more obvious evidences about the effect of liothyronine on prevention from memory impairment due to ECT.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was done with confirmation and financial support of Behavioral Sciences Research Center of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Authors thank the Isfahan Behavioral Sciences Research Center and personnel of different units of Department of Psychiatry in Noor Hospital, Isfahan, Iran.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prudic J. Kaplan & Sadock's comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. Eigth ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &; 2005. Electroconvulsive therapy; pp. 2968–83. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadock B, Sadock V. Kaplan & Sadock's synopsis of psychiatry. Tenth ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &; 2007. Electroconvulsive therapy; pp. 1118–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin Y, Elizur A, Korezyn AD. Physostigmine improves ECT-induced memory disturbances. Neurology. 1987;37:871–5. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.5.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prudic J, Fitzsimons L, Nobler MS, Sackeim HA. Naloxane in the prevention of the adverse cognitive effects of ECT. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:285–93. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horne RL, Pettineti HM, Menken M. Dexamethasone in electroconvulsive therapy. Biol Psychiatry. 1984;19:13–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tiurenkov IN, Bagmetov MN, Epishina VV. Comparative evaluation of neuroprotective activity of phenibut and piracetam under experimental cerebral ischemia in rats. Eksp Klin Farmakol. 2006;69:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tkachev AV. Application of nootropic agents in complex treatment of patients with concussion of the brain. Lik Sprava. 2007;5:82–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karahmadi M, Najimi MA. Piracetam effects on amnesia in depressed patients who are under electroconvulsive therapy at Noor Hospital.(Dissertation) Isfahan: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences; 2002. (in persion) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mindus P, Cronholm B, Levander SE. Does piracetam counteract the ECT-induced memory dysfunctions in depressed patients? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1975;51:319–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1975.tb00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hakkarainen H, Hakamies L. Piracetam in the treatment of postconcussional syndrome. Eur Neurol. 1978;17:50–5. doi: 10.1159/000114922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stern RA, Steketee MC, Durr AL. Combined use of thyroid hormone and ECT. Convuls Ther. 1993;9:285–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trement G, stern RA. Use of thyroid hormone to diminish the cognitive side effects of psychiatric treatment. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33:273–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mousavi SG, Navvab M. Effect of thyroid hormone on ECT-induced memory impairments at Noor Hospital. Isfahan: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences; 2005. (in Persion) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paller KA, Squire LR. Kaplan & sadock's comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. Lippincott Williams &: Philadelphia; 2005. Biology of Memory; pp. 553–65. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orangi M, Atef Vahid MK, Ashayeri H. Standardization of the revised Wechsler memory scale in Shiraz. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology (Andeesheh Va Raftar) 2002;28:56–66. [Google Scholar]