Abstract

Plastic pollution in the form of small particles (diameter less than 5 mm)—termed ‘microplastic’—has been observed in many parts of the world ocean. They are known to interact with biota on the individual level, e.g. through ingestion, but their population-level impacts are largely unknown. One potential mechanism for microplastic-induced alteration of pelagic ecosystems is through the introduction of hard-substrate habitat to ecosystems where it is naturally rare. Here, we show that microplastic concentrations in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (NPSG) have increased by two orders of magnitude in the past four decades, and that this increase has released the pelagic insect Halobates sericeus from substrate limitation for oviposition. High concentrations of microplastic in the NPSG resulted in a positive correlation between H. sericeus and microplastic, and an overall increase in H. sericeus egg densities. Predation on H. sericeus eggs and recent hatchlings may facilitate the transfer of energy between pelagic- and substrate-associated assemblages. The dynamics of hard-substrate-associated organisms may be important to understanding the ecological impacts of oceanic microplastic pollution.

Keywords: microplastic, marine debris, North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, Halobates sericeus, neuston

1. Introduction

Plastic accumulation in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (NPSG)—colloquially known as the ‘Great Pacific Garbage Patch’—has been a matter of public concern [1]. Before the advent of plastic marine debris, hard-substrate habitat in the NPSG was limited to relatively rare materials such as floating wood, pumice and seashells [2]. Despite this limitation, the NPSG houses a native substrate-associated rafting community that includes attached macroalgae, sessile as well as motile invertebrates and fishes [3]. The pelagic insect Halobates sericeus (Heteroptera: Gerridae), widespread across the eastern NPSG, belongs to both the surface-associated pelagic community (the ‘neuston’) and to the substrate-associated rafting community. Halobates sericeus moves freely over the air–sea interface where it preys on zooplankton, and is preyed upon by seabirds, marine turtles and surface-feeding fishes [4,5]. However, it requires hard substrates upon which to lay eggs, and therefore its reproduction is limited by the availability of floating materials [6].

Subtropical gyres are areas of convergence that accumulate particularly high concentrations of plastic marine debris [7–12]. Of this debris, the vast numerical majority is small fragments less than 5 mm in diameter, termed ‘microplastic’ [10–12]. Known environmental impacts of microplastic include ingestion by fishes and invertebrates [13–16], transport of organic pollutants [17] and alien species introduction [18]. To our knowledge, there have been no studies examining the effects of oceanic plastic debris on pelagic invertebrate communities. Because invertebrates are a critical link between primary producers and nekton, plastic-induced changes in their population structure could have ecosystem-wide consequences.

The goal of this study was to investigate the impact of microplastic debris as a novel habitat in the NPSG. To do this, we (i) quantified the increase in North Pacific microplastic over the past four decades; and (ii) correlated the increase in microplastic between 1972–1973 and 2009–2010 to changes in H. sericeus abundance.

2. Material and methods

We combined data from all available georeferenced peer-reviewed literature [7–11] and other publicly available sources [19] to compare changes in microplastic abundance between 1972–1987 and 1999–2010 (electronic supplementary material, table S1). For H. sericeus, we used surface samples collected by neuston nets at sea between 1972–1973 and 2009–2010 (complete methods in the electronic supplementary material).

Samples were sorted under a dissecting microscope. Halobates sericeus was enumerated and classified by eye, whereas microplastic particles were enumerated and measured using the Zooscan optical analysis system [10]. To determine the size range of particles used by H. sericeus for oviposition, the two-dimensional surface area and maximum diameter of a subset of plastic particles with attached eggs (n = 207) were measured using ImageJ (NIH). Dry mass of zooplankton and H. sericeus eggs were obtained from preserved samples.

We computed statistics using non-parametric methods in the R statistical environment (v. 2.13.1). Maps were created in Surfer v. 8 (Golden Software), and interpolated using point kriging. New data from this study are deposited with the California Current Ecosystem LTER DataZoo (http://oceaninformatics.ucsd.edu/datazoo/data/ccelter/datasets?action=group&id=1).

3. Results

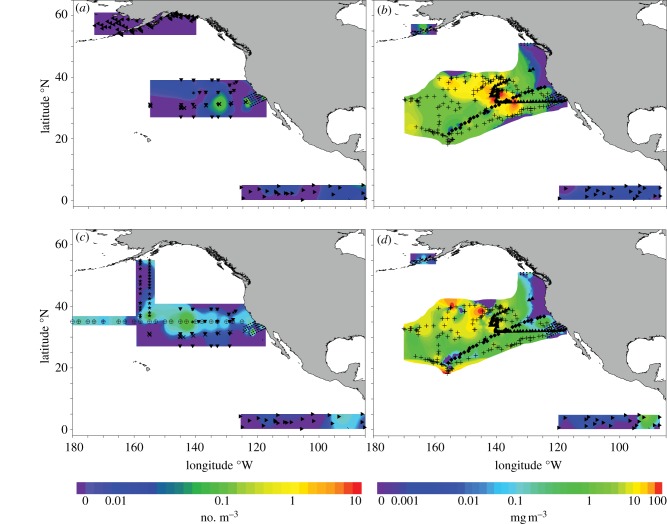

Microplastic debris in the North Pacific increased by two orders of magnitude between 1972–1987 and 1999–2010 in both numerical (NC) and mass concentrations (MC; figure 1 and electronic supplementary material, table S2). In 1972–1987, no microplastic was found in more than half of the samples (median NC = 0 particles m–3, MC = 0 mg m−3). By 1999–2010, median NC had increased significantly to 0.116 particles m−3 and MC to 0.086 mg m−3 (all following are two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-tests, NC = p < 0.0001; MC = p < 0.0001). This increase was driven primarily by an increase in microplastic abundance in the NPSG (electronic supplementary material, table S2; NC: p < 0.0001; MC: p < 0.0001). Although a significant increase in NC was also found off Alaska (electronic supplementary material, table S2; p = 0.0197), MC remained unchanged (p = 0.3711). There was no significant change in the California Current [10] or the Eastern Tropical Pacific (electronic supplementary material, table S2; NC: p = 0.3332; MC: p = 0.2528). These results were confirmed when we conducted additional subsampling as controls for regional and seasonal variation (see electronic supplementary material).

Figure 1.

Microplastic concentrations in 1972–1987 and 1999–2010. Numerical concentration (no. m−3) for (a) 1972–1987 and (b) 1999–2010; microplastic mass concentration (mg m−3) for (c) 1972–1987 and (d) 1999–2010. New data from this study include 7205 (asterisks), 7210 (inverted triangles), Southtow 13 (cross symbols), STAR (right-facing triangles), SEAPLEX (triangles) and EX1006 (diamonds). Published data are Wong et al. [7] (crossed circles), Shaw [8] (stars), Day & Shaw [9] (left-facing triangles), Gilfillan et al. [10] (filled circles) and Doyle et al. [11] (filled circles). Gilfillan et al. [10] and Doyle et al. [11] have overlapping stations. Non-peer-reviewed publicly available data from Algalita Marine Research Foundation [19] (plus symbols).

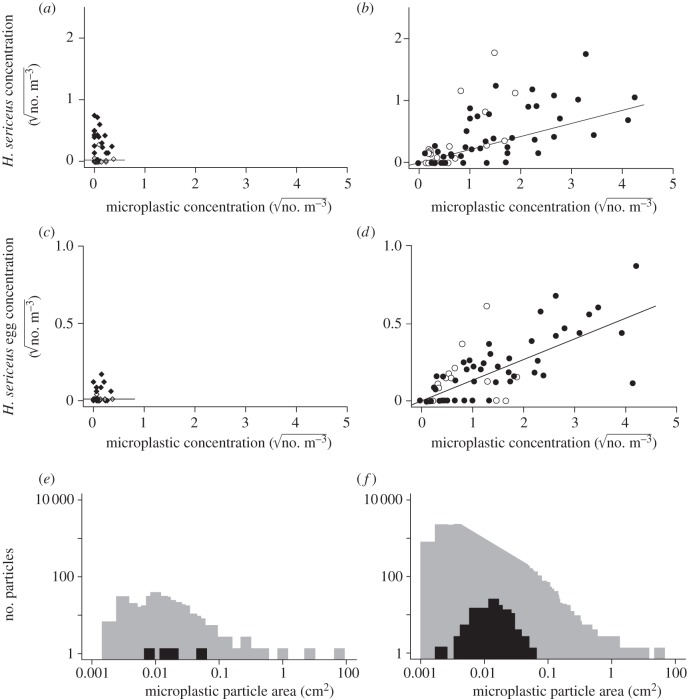

We found no association between microplastic concentration and the abundance of H. sericeus adults/juveniles in 1972–1973 (figure 2a), but a positive association in 2009–2010 (figure 2b). Similarly, there was no association between microplastic concentration and the abundance of H. sericeus eggs deposited on microplastic in 1972–1973 (figure 2c), but a positive association in 2009–2010 (figure 2d). We also found a significant increase in the median abundance of H. sericeus adults/juveniles and eggs (two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test, adults/juveniles, p = 0.0024, eggs p < 0.0001). When seasonal variation in H. sericeus abundance was controlled by restricting the comparison to October 1972 and October 2010, egg abundance increased with plastic particle abundance (one-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test, p = 0.0497), but not adult/juvenile abundance (p = 0.8680).

Figure 2.

Halobates sericeus adult and juvenile numerical concentration (NC) versus microplastic NC in 1972–1973 (a: Spearman rank correlation, p = 0.3644; r2 = 0.019) and 2009–2010 (b: Spearman rank correlation, p < 0.0001; r2 = 0.404); H. sericeus egg NC versus microplastic NC in 1972–1973 (c: Spearman rank correlation p = 0.0614; r2 = 0.079) and 2009–2010 (d: Spearman rank correlation, p < 0.0001; r2 = 0.512). Also shown are size–frequency histograms for all microplastic particle areas (grey) and particles with attached eggs (black) in (e) 1972–1973 and (f) 2009–2010. Symbols (a–d) represent dates of data collection: spring 1972 (grey diamonds), autumn 1972 (filled diamonds), winter 1973 (open diamonds), summer 2009 (filled circles) and autumn 2010 (open circles). Only particles in the size range used by H. sericeus were used to calculate microplastic NC (a–d). Eggs in the samples for (e) were dislodged from their original substrate (63%) are excluded from this figure.

Halobates sericeus eggs measured 0.8–1.2 mm in length and were found on microplastic particles ranging from 0.002 to 0.054 cm2 (M = 0.015), a size class that includes 81.2 per cent of all particles collected in 2009–2010 (figure 2e,f). We estimate that the biomass of one to three eggs is equivalent to 9.2–27.6% of the daytime zooplankton biomass over 1 m2 of the top 20 cm of surface water.

4. Discussion

Our study associates the dramatic increase in microplastic abundance in the past 40 years with oviposition of H. sericeus, an abundant and conspicuous member of the NPSG pelagic community. Intra- and inter-annual samples from the NPSG in the intervening decades are not available, so we cannot rule out the possibility that there might be a more variable temporal pattern. However, the long-term trend supports a significant increase in microplastic concentration.

The abundance of both microplastic and H. sericeus are spatially and temporally heterogeneous within the NPSG, but H. sericeus is highly mobile and can skate at speeds up to 0.8–1.3 m s−1 [4]. If H. sericeus acted as a passive particle on the ocean surface, then a positive correlation between it and plastic abundance would be expected in all sampling periods. We found no such correlation for either adults/juveniles or eggs in 1972–1973, but a significant correlation for both adults/juveniles and eggs in 2009–2010 (figure 2). We interpret this to mean that microplastic increase has released this pelagic insect from substrate limitation for oviposition.

We estimated the increase in hard substrate in the top 20 cm of the NPSG (4 × 106 km3; [20]). Microplastic particles in the size range used by H. sericeus increased from a median NC of 0.002 particles m−3 in 1972–1973 to 1.194 in 2009–2010, with a decrease in median surface area from 0.016 cm2 to 0.015 cm2. It should be noted that these microplastic NC are higher than those previously reported [2,10–12], potentially due to targeted sampling of high-plastic areas in our study. We caution that this is a rough approximation, but nonetheless suggests a substantial expansion of hard substrate available to H. sericeus and other substrate-associated organisms.

Predation on eggs and recent hatchlings may limit H. sericeus populations and transfer energy between pelagic and substrate-associated communities. For example, the epipelagic crab Planes minutus is known to prey on both Halobates individuals and eggs in the Atlantic Ocean [4]. Because eggs are equivalent to a substantial percentage (9.2–27.6%) of daytime NPSG biomass, they may be an efficient target for predators such as epipelagic crabs and omnivorous fishes, both of which were observed to be abundant during 2009–2010 sampling. Halobates sericeus is capable of oviposition on large items [6], but no eggs were found on large items in 2009–2010, suggesting that eggs may be removed from microplastic particles by predators.

The novel ecological interactions caused by the introduction of plastic particles to oceanic ecosystems, termed the ‘plastisphere’ [21], may transfer energy between pelagic and substrate-associated assemblages [3]. If microplastic densities continue to increase, then substrate-associated biota such as H. sericeus may be expected to increase as well, potentially at the expense of prey such as zooplankton or fish eggs [3,4]. Future work should incorporate the dynamics of substrate-associated assemblages with ongoing work in toxicology [17], microbial ecology [21] and faunal interactions [13–16] to provide a better understanding of the impact of microplastic pollution on pelagic marine ecosystems.

Acknowledgements

Funding for SEAPLEX was provided by University of California Ship Funds, Project Kaisei/Ocean Voyages Institute, AWIS-San Diego, and NSF IGERT (grant no. 0333444). EX1006 samples courtesy of the NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, 2010 Always Exploring expedition, made possible by M. Ford. M.C.G. was supported by donations from Jim & Kris McMillan, Jeffrey & Marcy Krinsk, Lyn & Norman Lear, Ellis Wyer and an anonymous donor. Assistance from the crews of the R/V New Horizon and R/V Okeanos Explorer, L. Gilfillan, A. Townsend, L. Sala, the SIO Pelagic Invertebrate Collection, the CCE LTER site supported by NSF and many laboratory volunteers made this project possible. We thank Algalita Marine Research Foundation for their publicly available data. Conversations with M.D. Ohman, J. Drew, and J.E. Byrnes and comments from M. Thiel and an anonymous reviewer greatly improved this manuscript.

References

- 1.Kaiser J. 2010. The dirt on ocean garbage patches. Science 328, 1506. 10.1126/science.328.5985.1506 (doi:10.1126/science.328.5985.1506) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thiel M., Gutow L. 2005. The ecology of rafting in the marine environment. I. The floating substrata. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 42 181–263 10.1201/9780203507810.ch6 (doi:10.1201/9780203507810.ch6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thiel M., Gutow, L. 2005. The ecology of rafting in the marine environment. II. The rafting organisms and community. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 43, 279–418 10.1201/9781420037449.ch7 (doi:10.1201/9781420037449.ch7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen N. N., Cheng L. 2004. The marine insect Halobates (Heteroptera: Gerridae): biology, adaptations, distribution and phylogeny. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 42, 119–180 10.1201/9780203507810.ch5 (doi:10.1201/9780203507810.ch5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng L., Spear L., Ainley D. G. 2010. Importance of marine insects (Heteroptera: Gerridae, Halobates spp.) as prey of eastern tropical Pacific seabirds. Mar. Ornithol. 38, 91–95 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng L., Pitman R. L. 2002. Mass oviposition and egg development of the ocean-skater Halobates sobrinus (Heteroptera: Gerridae). Pac. Sci. 56, 441–447 10.1353/psc.2002.0033 (doi:10.1353/psc.2002.0033) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong C. S., Green D. R., Cretney W. J. 1974. Quantitative tar and plastic waste distributions in Pacific Ocean. Nature 247, 30–32 10.1038/247030a0 (doi:10.1038/247030a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw D. G. 1977. Pelagic tar and plastic in the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea: 1975. Sci. Total Environ. 8, 13–20 10.1016/0048-9697(77)90058-4 (doi:10.1016/0048-9697(77)90058-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Day R. H., Shaw D. G. 1987. Patterns in the abundance of pelagic plastic and tar in the north Pacific Ocean, 1976–1985. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 18, 311–316 10.1016/S0025-326X(87)80017-6 (doi:10.1016/S0025-326X(87)80017-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilfillan L. R., Ohman M. D., Doyle M. J., Watson W. 2009. Occurrence of plastic micro-debris in the southern California Current system. Cal. Coop. Ocean. Fish. 50, 123–133 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doyle M. J., Watson W., Bowlin N. M., Sheavly, S. B. 2011. Plastic particles in coastal pelagic ecosystems of the Northeast Pacific ocean. Mar. Environ. Res. 71, 41–52 10.1016/j.marenvres.2010.10.001 (doi:10.1016/j.marenvres.2010.10.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hidalgo-Ruz V., Gutow L., Thompson R. C., Thiel M. 2012. Microplastics in the marine environment: a review of the methods used for identification and quantification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 3060–3075 10.1021/es2031505 (doi:10.1021/es2031505) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boerger C. M., Lattin G. L., Moore S. L., Moore C. J. 2010. Plastic ingestion by planktivorous fishes in the North Pacific Central Gyre. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 60, 2275–2278 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.08.007 (doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.08.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davison P., Asch R. G. 2011. Plastic ingestion by mesopelagic fishes in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 432, 173–180 10.3354/meps09142 (doi:10.3354/meps09142) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson R. C., Olsen Y., Mitchell R. P., Davis A., Rowland S. J., John A. W. G., McGonigle D., Russell A. E. 2004. Lost at sea: Where is all the plastic? Science 304, 838. 10.1126/science.1094559 (doi:10.1126/science.1094559) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Browne M. A., Dissanayake A., Galloway T. S., Lowe D. M., Thompson R. C. 2008. Ingested microscopic plastic translocates to the circulatory system of the mussel, Mytilus edulis (L). Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 5026–5031 10.1021/es201811s (doi:10.1021/es201811s) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teuten E. L., et al. 2009. Transport and release of chemicals from plastics to the environment and to wildlife. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 2027–2045 10.1098/rstb.2008.0284 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0284) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnes D. K. A. 2002. Invasions by marine life on plastic debris. Nature 416, 808–809 10.1038/416808a (doi:10.1038/416808a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Algalita Marine Research Foundation 2002–2011. Mapping plastic pollution: GIS Maps of plastic density in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (NPSG). See http://www.algalita.org/research/Maps_Home.html

- 20.Karl D. M. 1999. Minireviews: a sea of change: biogeochemical variability in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. Ecosystems 2, 181–214 10.1007/s100219900068 (doi:10.1007/s100219900068) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zettler E. R., Mincer T., Proskurowski G., Amaral-Zettler L. A. 2011. The ‘plastisphere’: a new and expanding habitat for marine protists. J. Phycol. 47, S45 [Google Scholar]