Abstract

Theories on the development and evolution of teeth have long been biased by the fallacy that chondrichthyans reflect the ancestral condition for jawed vertebrates. However, correctly resolving the nature of the primitive vertebrate dentition is challenged by a dearth of evidence on dental development in primitive osteichthyans. Jaw elements from the Silurian–Devonian stem-osteichthyans Lophosteus and Andreolepis have been described to bear a dentition arranged in longitudinal rows and vertical files, reminiscent of a pattern of successional development. We tested this inference, using synchrotron radiation X-ray tomographic microscopy (SRXTM) to reveal the pattern of skeletal development preserved in the sclerochronology of the mineralized tissues. The tooth-like tubercles represent focal elaborations of dentine within otherwise continuous sheets of the dermal skeleton, present in at least three stacked generations. Thus, the tubercles are not discrete modular teeth and their arrangement into rows and files is a feature of the dermal ornamentation that does not reflect a polarity of development or linear succession. These fossil remains have no bearing on the nature of the dentition in osteichthyans and, indeed, our results raise questions concerning the homologies of these bones and the phylogenetic classification of Andreolepis and Lophosteus.

Keywords: Osteichthyes, Andreolepis, Lophosteus, tooth, development, evolution

1. Introduction

Chondrichthyans (cartilaginous fishes) have long been considered a model for rationalizing the evolutionary origin of the vertebrate dentition and, consequently, patterns of development and developmental evolution among osteichthyans (bony fishes including tetrapods) [1]. However, the nature of the ancestral gnathostome dentition and its development can only be inferred through comparative analysis of chondrichthyans, osteichthyans and their extinct sister lineages. This aim is challenged most especially by a dearth of evidence on dental development in stem-osteichthyans. The description of a dentary bone of Andreolepis and a maxillary bone of Lophosteus, both interpreted as stem-osteichthyans [2], holds the promise of a fundamental insight into the mode of dental development primitive to osteichthyans and gnathostomes more generally.

These dermal jaw elements of both Lophosteus and Andreolepis are covered with tubercles that have been interpreted as organized into longitudinal rows and transverse files, reminiscent of a pattern of successional development, such as that seen in chondrichthyan teeth [2]. Indeed, this inferred pattern of dental development, without shedding or replacement, has been suggested to illustrate an early stage of osteichthyan tooth patterning [2]. Inferences of skeletal development from surface morphology are problematic but the fossil remains are too rare to apply the conventional destructive histological methods needed to test the inferred pattern of development. Therefore, we employed synchrotron radiation X-ray tomographic microscopy (SRXTM), a non-invasive means of obtaining a high-resolution volumetric virtual characterization of the fossil remains in which to investigate skeletal development.

2. Material and methods

Two specimens were used in the analyses. An incomplete putative right dentary of Andreolepis hedei from the Upper Silurian (Ludlow) of Gogs, Gotland, Sweden, housed in the Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm (NRM-PZ P. 15910). A putative right maxillary of Lophosteus superbus from an Upper Silurian (Middle–Upper Pridoli) erratic boulder from Germany (also figured by Botella et al. [2, fig. 2a–d]) is reposited at the Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin (MB.f.17035). Volumetric characterization of the specimens was achieved using SRXTM [3]. The analyses were carried out at the X02DA (TOMCAT) beamline at the Swiss Light Source, Paul Scherrer Institut, Villigen. The virtual slice data were visualized using Avizo 6.3 (www.vsg3d.com). ‘Virtual thin sections’ were created using the voltex module in Avizo, which simulates the casting of light rays from preset sources through a volume of data.

3. Results

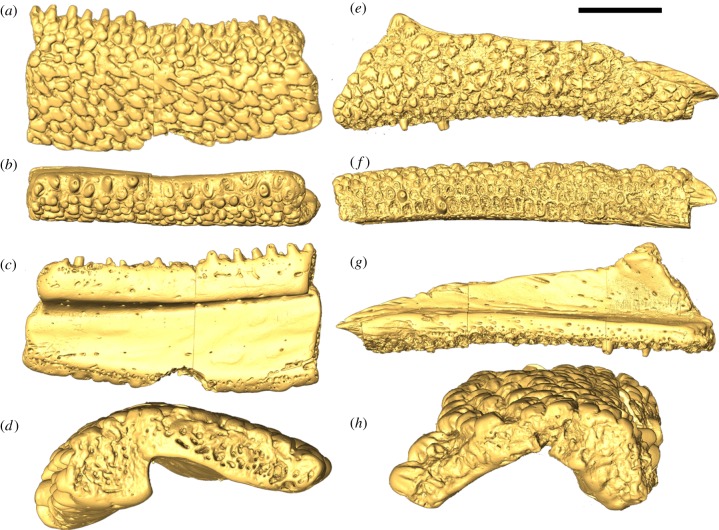

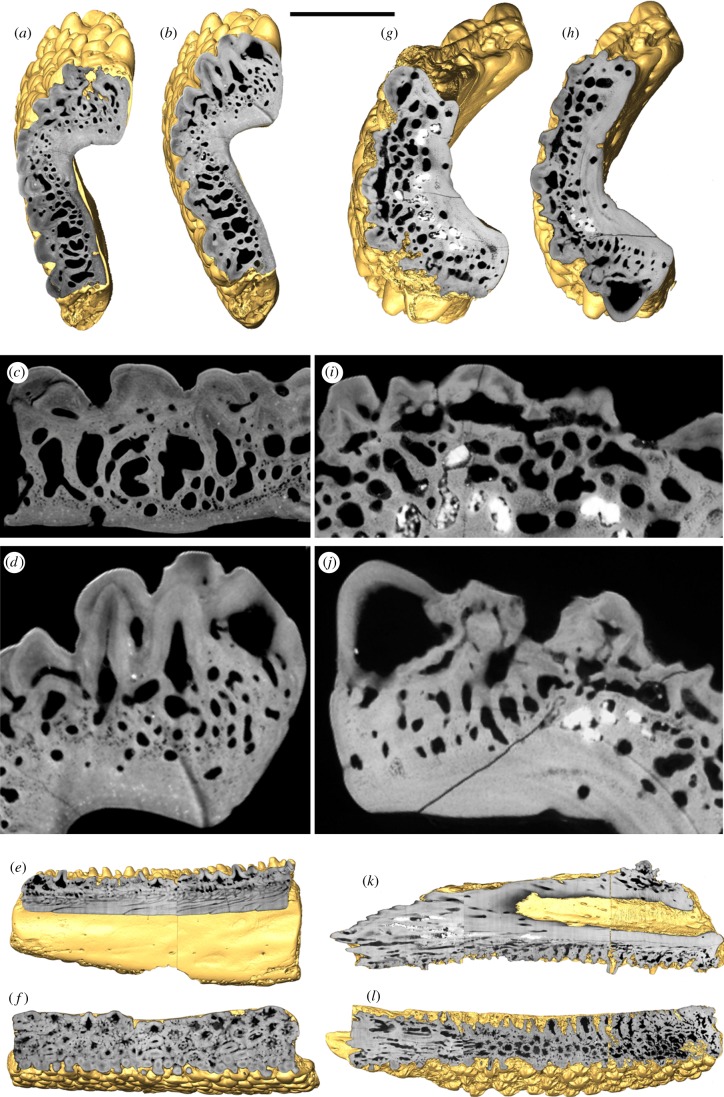

The dermal plates of both Andreolepis (figures 1a–d and 2a–d) and Lophosteus (figures 1e–h and 2e–h) exhibit a similar gross histological architecture comprising a basal division of compact lamellar bone that intergrades with a middle division of vascular or cancellar bone rich in osteocyte lacunae. The superficial division includes tubercles composed of dentine surrounding spurs of the vascular network. In both taxa, the tubercles reflect different developmental generations, evidenced by their vertical or lateral overlap.

Figure 1.

Surface renderings (gold) of (a–d) Andreolepis and (e–h) Lophosteus based on SRXTM data. (a) Lateral, (b) dorsal, (c) medial and (d) posterior views of the putative right dentary of Andreolepis (NRM-PZ P.15910). (e) Lateral, (f) ventral, (g) medial and (h) posterior views of the putative right plate of Lophosteus superbus MB.f.17035. Scale bars: (a–c) 1.71 mm; (d) 0.54 mm; (e–g) 2 mm; (h) 0.9 mm.

Figure 2.

Surface renderings (gold) of (a–f) Andreolepis and (g–l) Lophosteus cut by ‘virtual thin sections’ based on SRXTM data. (a–d) Transverse, (e) longitudinal, and (f) horizontal surface cuts of the putative right dentary of Andreolepis (NRM-PZ P. 15910); (c) and (d) are enlargements of the sections shown in (a) and (b), respectively. (g–j) Transverse, (k) longitudinal and (l) horizontal surface cuts of the putative right maxillary of Lophosteus superbus MB.f.17035; (i) and (j) are enlargements of the sections shown in (g) and (h), respectively. Scale bars: (a,b) 0.8 mm; (c) 0.3 mm; (d) 0.35 mm; (e,f) 2 mm; (g,h) 1 mm, (i) 0.4 mm; (j) 0.3 mm; (k,l) 2.4 mm.

In the putative dentary of Andreolepis, the vascularization of the bone is thinnest in radial extent in the region of the longitudinal concavity (figure 2a,b) where the compact lamellar basal layers are proportionally more extensively developed. Vascularization increases away from the longitudinal concavity, dorsally and ventrally (following the orientations inferred [2]; figure 2a,b). Growth arrest lines within the middle layer evidence the appositional growth of the plate dorsally and, especially, ventrally, with concomitant growth of the basal and superficial layers (figure 2d). However, growth of the superficial layer was not limited to the dorsal and ventral margins of the plate, with successive generations of dermal tubercles intercalating, overlapping and enveloping those already present (figure 2c). Nevertheless, the dermal tubercles that comprise the entire superficial layer occur as a sequence of superimposed laterally continuous sheets (figure 2a–d). The tubercles exhibit simple undivided pulp cavities and a distinct highly attenuating and therefore hypermineralized capping tissue (figure 2c–d). The height of tubercles increases towards the external face of the dorsal margin of the plate, and those on the extreme margin of the plate (figure 1a–d) are clearly associated morphogenetically with the appositional growth of the whole plate (figure 2d).

In Lophosteus, the putative maxillary plate shows some variation in the proportional development of the spongy vascular bone and the compact lamellar bone at the base, from inferred proximal to distal. Distally, the spongy bone comprises the plate almost wholly (figure 2g), while more proximally the compact basal bone layer comprises as much as half the radial thickness of the plate (figure 2h), with vascular canals extending from the inner surface to the overlying vascular network (figure 2g,h,k). The tubercles are generally rounded in outline and have low relief (figure 1e–h), exhibiting divided pulp cavities with numerous vascular loops (figure 2g–j). The tubercles show evidence of appositional growth in the direction of the presumed dorsal and ventral margins of the plate, and these appositional events are continuous with growth arrest lines in the vascular and compact bone, indicating growth only at the lateral and inner surfaces (figure 2i,j). At the presumed ventral margin, the tubercles have a distinct conical morphology with comparatively high relief (figure 1a,c,e–g); the pulp cavities are undivided and, generally, unfilled (figure 2i,j). There is no evidence for a differentiated capping tissue.

4. Discussion

Evidently, the tubercles comprising the superficial layer of the presumed dentary of Andreolepis and maxillary plate of Lophosteus developed in association with marginal accretion of the underlying dermal plate. There is some evidence of tubercles augmenting the central face of the plate, isolated from marginal appositional growth, but these are local morphogenetically continuous associations of tubercles. This mode of development is not compatible with expectations of tooth development. Teeth invariably develop as morphogenetically distinct elements, fused, ankylosed and/or socketed with the associated dermal plate. The tubercles comprising the superficial layer of these dermal plates are more reminiscent of the tubercles that develop in association with the dermal skeleton more generally. The polarization of the tubercles on the surface of the dermal plates does not reflect a pattern of tooth succession but, rather, reflects marginal growth associated with the expansion in size of the dermal plate. In the specimen of Andreolepis, the apparent successive rows of tubercles comprising the tooth-like margin of the plate are all products of the same morphogenetic event and so the arrangement reflects a spatial organization rather than a pattern of linear succession.

Although the tubercles associated with the dorsal margin of the presumed dentary and ventral margin of the presumed maxilla exhibit a tooth-like morphology, in the Andreolepis plate, they intergrade continuously with the morphology of the tubercles away from this margin (figures 1a–d and 2a–d). The case for a tooth-like morphology appears clearer in Lophosteus, since these conical marginal tubercles differ from the rounded tubercles that occur deep to this margin. However, this distinction flatters to deceive since the intervening tubercles have been eroded away. From what little remains, in terms of the dimensions of the pulp cavities, it appears that the tubercles increase in size gradually, from the tubercles in the plate centre, towards the plate margin (figure 1e–h).

Therefore, our tomographic data reveal that neither Andreolepis nor Lophosteus grew by sequential addition of tubercles at the medial margin, as previously inferred from external morphology [2]. The structure and pattern of development of the dermal plates is generally representative of dermal bones of these taxa [4,5]. These findings are incompatible with Lophosteus or Andreolepis tubercles growing in files similar to the tooth ‘families’ of chondrichthyans and some acanthodians, or to the shedding tooth rows of crown-osteichthyans. There is therefore no support for the presence of tooth ‘capsules’ acting as separate functional modules. This is not to say that Andreolepis and Lophosteus lacked teeth, not least since Gross [6] has described isolated toothwhorl-like aggregates of tubercles associated with Lophosteus, rather, that there is no evidence for teeth among the specimens that we describe. As such, these dermal plates do not evidence an incipient osteichthyan dentition, such as might be expected by hypotheses that seek to explain the evolutionary origin of teeth through the heterotopic extension of odontogenic competence from the external dermis to the oral cavity.

As the bones do not have incipient teeth it is appropriate to reconsider their homology with osteichthyan dentary and maxillary bones. This is not the only line of evidence used to identify the bones as jaw elements. Botella et al. [2] justify homology on the presence of a narrow medial horizontal lamina, the presence of upper and lower overlapping plate margins, and the general similarity to the maxilla of osteichthyan maxillary plates. However, the dermal histology of Lophosteus is uncharacteristic of osteichthyans and shows greater similarity to the placoderm dermoskeleton. Typical osteichthyan characters are absent also from the putative dentary of Andreolepis, such as the absence of a closed sensory-line canal that is characteristic of osteichthyan lower jaws, though its histological structure is more typically osteichthyan. These observations have implications for resolving the phylogenetic affinities of Andreolepis and Lophosteus, which have proven to be contentious. Andreolepis has generally been interpreted as a primitive actinopterygian [4,7,8] or a stem osteichthyan [2,9], but similarities to sarcopterygians and acanthodians have also been noted [4,10]. Apart from the interpreted dentary bone, the only remaining characters used to place Andreolepis in the osteichthyan total group are rhombic scales with ganoine/enamel, possible fulcral scales, and a possible cleithrum [9]. Lophosteus has been compared with crown or stem-osteichthyans [2,5,6,11–13], placoderms [14], and acanthodians [6,13,15]. Rhombic scales are the only osteichthyan character currently known in Lophosteus other than the maxillary bone [9]. If the jaw characters are removed, the remaining osteichthyan characters of both taxa are few in number and their identification is often tentative. The chimaeric assemblage of characteristics exhibited by Lophosteus and Andreolepis may reflect the paucity of our understanding of the phylogenetic distribution of these characters, some of which may be crown-gnathostome, or primitive to jawed vertebrates more generally.

5. Conclusions

The tomographic data presented here show that the tubercles of Andreolepis and Lophosteus were neither added sequentially at the medial margin, nor arranged in single tooth files. Instead there is evidence that tubercles represent focal elaborations of dentine within continuous sheets of dermal bone. This demonstrates that the tubercles of these taxa did not grow in a similar way to the teeth of either chondrichthyans or crown group osteichthyans. Instead their ontogeny is comparable to that observed in dermal scales. As a result, these structures are uninformative regarding the origin of osteichthyan dentition.

References

- 1.Reif W.-E. 1982. Evolution of dermal skeleton and dentition in vertebrates: the odontode regulation theory. Evol. Biol. 15, 287–368 10.1007/978-1-4615-6968-8_7 (doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-6968-8_7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botella H., Blom H., Dorka M., Ahlberg P. E., Janvier P. 2007. Jaws and teeth of the earliest bony fishes. Nature 448, 583–586 10.1038/Nature05989 (doi:10.1038/Nature05989) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donoghue P. C. J., et al. 2006. Synchrotron X-ray tomographic microscopy of fossil embryos. Nature 442, 680–683 10.1038/Nature04890 (doi:10.1038/Nature04890) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gross W. 1968. Fragliche Actinopterygier-Schuppen aus dem Silur Gotlands. Lethaia 1, 184–218 10.1111/j.1502-3931.1968.tb01736.x (doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1968.tb01736.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross W. 1969. Lophosteus superbus Pander, ein Teleostome aus dem Silur Oesels. Lethaia 2, 15–47 10.1111/j.1502-3931.1969.tb01249.x (doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1969.tb01249.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gross W. 1971. Lophosteus superbus Pander: Zähne, Zahnknochen und besondere Schuppenformen. Lethaia 4, 131–152 10.1111/j.1502-3931.1971.tb01285.x (doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1971.tb01285.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schultze H.-P. 1977. Ausgangsform und Entwicklung der rhombischen Schuppen der Osteichthyes (Pisces). Paläont Z. 51, 152–168 10.1007/BF02986565 (doi:10.1007/BF02986565) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Märss T. 2001. Andreolepis (Actinopterygii) in the Upper Silurian of northern Eurasia. Proc. Estonian Acad. Sci. Geol. 50, 174–189 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman M., Brazeau M. D. 2010. A reappraisal of the origin and basal radiation of the osteichthyes. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 30, 36–56 10.1080/02724630903409071 (doi:10.1080/02724630903409071) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janvier P. 1978. On the oldest known teleostome fish Andeolepis hedei Gross (Ludlow of Gotland) and the systematic position of the lophosteids. Proc. Estonian Acad. Sci. Geol. 27, 88–95 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pander C. H. 1856. Monographie der fossilen Fische des silurischen Systems der Russisch-Baltischen Gouvernements, 91p. St Petersburg, Russia: Akademie der Wissenschaften [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohon J. V. 1893. Die Obersilurischen Fische von Oesel. Theil 2. Mém. Acad. Imp. Sci. St Petersbourg 41, 1–124 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schultze H.-P., Märss T. 2004. Revisiting Lophosteus, a primitive osteichthyan. Acta. Univ. Latv. 674, 57–78 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burrow C. J. 1995. A new lophosteiform (Osteichthyes) from the Lower Devonian of Australia. Geobios. Mémoire. Spécial. 19, 327–333 10.1016/S0016-6995(95)80134-0 (doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(95)80134-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otto M. 1991. Zur systematischen Stellung der Lophosteiden (Obersilur, Pisces inc. sedis). Paläont. Z. 65, 345–350 10.1007/BF02989850 (doi:10.1007/BF02989850) [DOI] [Google Scholar]