Abstract

This is an observational case series of five cases of acute acquired comitant esotropia (AACE) with diplopia, aged between 5 and 12 years. The duration of presenting complaints ranged from 4 days to 2 months. A detailed ophthalmic evaluation and neuroimaging were done on all patients. Three patients were found to have intracranial pathology. Two patients had pontine glioma and one patient had benign intracranial hypertension. One patient was diagnosed as accommodative spasm and one patient was diagnosed as having Type 2 AACE.

We would like to conclude that AACE can be of a varied aetiology ranging from convergence spasm to those harboring serious intracranial diseases. We reiterate that AACE has a small but significant association with intracranial disorders. Neuroimaging is a definite need in cases which cannot be proved to be either Type 1 or 2.

Keywords: Acute acquired comitant, aetiology, esotropia neuroimaging

Introduction

Acute acquired comitant esotropia (AACE) has been used to describe a dramatic onset of a relatively large angle esotropia with diplopia and minimal refractive error.[1,2] The prevalence of acute esotropia is not known, but is considered rare.[3] It has been classified into three forms. (1) That occurring after artificial interruption of binocular vision; (Swan type). (2) That occurring without interruption of binocular vision as a result of a decompensated esophoria; (Franceschetti). (3) That caused by an intracranial pathologic process.[2]

Case Report

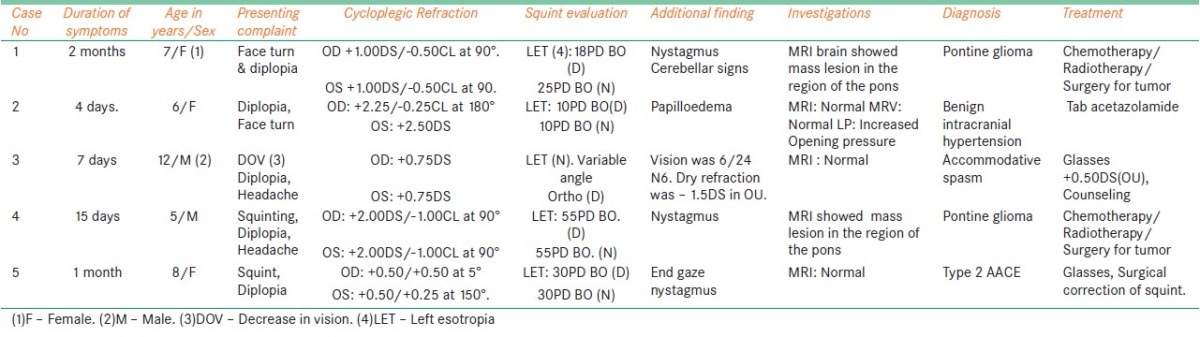

We present a series of five cases who presented with diplopia that developed acutely, ranging from 4 days to 2 months. The details of the cases are as given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Table showing the clinical features of the five cases with acute acquired comitant esotropia

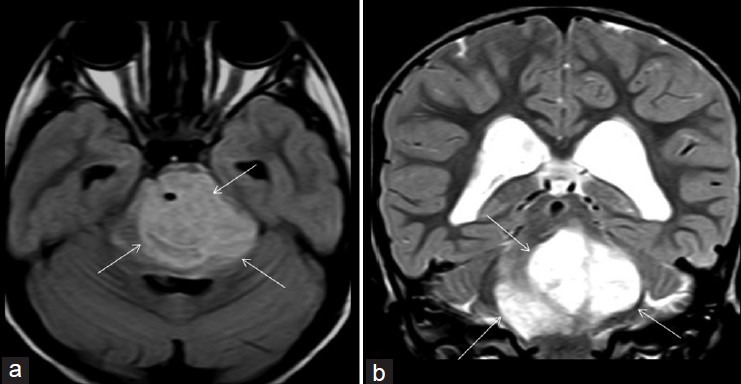

The patient's age ranged from 5 to 12 years. All patients complained of diplopia. The duration of presenting complaints ranged from 4 days to 2 months. None of the patients had a preceding infection, undue tiredness, difficulty in swallowing, ptosis intermittency in strabismus, associated pattern, or history of occlusion of one eye. Extra ocular movements were full in all the cases. [Figure 1]. Case one and case four had floating saccades in horizontal versions. The esodeviation was comitant and there was no difference in the angle of squint with either eye fixing. Case one had esotropia more for distance than near and case three had esotropia only for near. The rest had equal amounts of esotropia for distance and near. Visual acuity was 6/6 N6 in all eyes except case three in which vision was 6/24 N6 in both eyes. A cycloplegic retinoscopy was performed on each patient. All patients had a low hyperopic refractive error. Fundus evaluation was done by indirect ophthalmoscopy. The fundus was normal in all cases except for case two, which had papilloedema. [Figure 2a]. In addition to the ophthalmic examination, each child was examined by a neurologist and underwent neuroimaging. Case one and case four had a space occupying lesion (Pontine glioma). [Figure 3] Case one and case four with pontine glioma underwent surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Case one succumbed to her disease and case four was lost for follow up.

Figure 1.

Picture of case five showing left esotropia with full horizontal versions

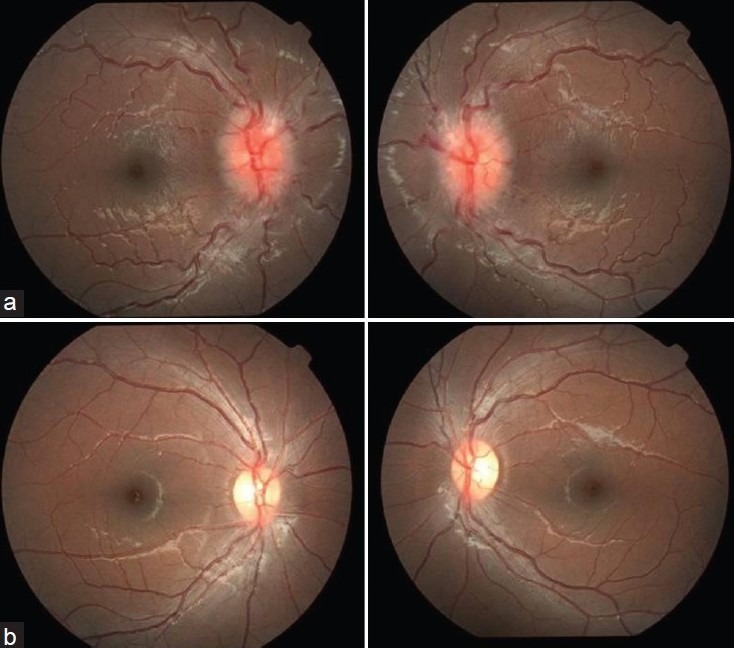

Figure 2.

(a) Fundus photograph of the right and left eye of case two showing papilloedema (b) Fundus photograph of the right and left eye of case two showing normal discs after treatment

Figure 3.

Axial FLAIR (a) and coronal (b) MRI brain showing a large intra-axial lesion (arrows) with cystic and solid component most likely a glioma causing expansion of the brain stem

Case two had a normal MRI and MRV. A lumbar puncture revealed a raised opening pressure and was diagnosed as benign intracranial hypertension by the neurologist and treated with acetazolamide. She recovered completely with resolved papilloedema, [Figure 2b] to record a stereo acuity of 70 arc seconds (Titmus test) 2 months after her medical treatment.

Case three was diagnosed as spasm of accommodation based on the presence of variable angle esotropia for near, a myopic dry refraction, and hyperopic cycloplegic refraction. He was given glasses and counseled.

Case five was diagnosed to have a Type 2 AACE.[2] She was given glasses and reevaluated after 2 months. There was no change in her squint with glasses. A recession/resection procedure was done in her left eye. She is doing well postoperatively.

Discussion

The association of AACE with tumors of the posterior fossa is well-known.[4] Neuroimaging was done for the following reasons in each case; cases one, four, and five had nystagmus,[1,2] case three came with diplopia, esotropia, and headache, and case four had papilloedema. Among the five patients, three had an underlying intracranial pathology. Case one had an esotropia more for distance than near and cases one and four, who had pontine glioma, also had floating saccades. There was no associated V pattern and the esotropia was the same in all positions of gaze. V pattern could have gone more in favor of a sixth nerve palsy.[1] Even then; it could be possible that there initially was an abducens palsy which recovered. In cases of mild sixth nerve palsy in children the lateral rectus can recover quickly, but a comitant, moderate angled esotropia may remain.[5] Patients with tumors of the infratentorial space may develop obstructive hydrocephalus and secondary esodeviation because of elevated intracranial pressure. Alternatively, they may develop an esodeviation by primary interference with pontine or cerebellar oculomotor control mechanisms responsible for maintaining horizontal ocular alignment.[6]

Case two was diagnosed as benign intracranial hypertension (BIH). AACE is known to be associated with BIH.[7,8] Reversal of the cranial nerve palsy with lowering of the intracranial pressure is required to associate the palsy with BIH.[7] Our patient had a complete recovery of the acute esotropia with medical treatment.

Contrary to the report that AACE is common and benign and does not need neuroimaging,[3] we believe it is still an uncommon condition, which has to be evaluated meticulously, to search for signs indicative of central nervous system involvement. We feel that it is better to err on the side of getting a neuroimaging done since the association with intracranial tumors is ominous and life threatening.

Case three was diagnosed to have an accommodative spasm. This typically presents with intermittent esotropia and diplopia for near. The esotropia tends to be variable and miosis of the pupils accompanies the misalignment.[9] Most causes of spasm of the near reflex are nonorganic, though some cases have been reported after closed head trauma,[10] intracranial tumors, or chiari malformation.[4] Case 3 presented to us 3 days after initial presentation with severe headache, which prompted us to get a neuroimaging done.

Case five was diagnosed to have a Type 2 AACE.[2] This could have resulted from a decompensated esophoria. She was given glasses and reevaluated after 2 months. There was no change in her squint with glasses. A recession/resection procedure was done in her left eye. She is doing well postoperatively.

Conclusion

Acute onset esotropia can be of a varied aetiology ranging from convergence spasm, to those harboring serious intracranial diseases. We reiterate that AACE has a small but significant association with intracranial disorders. Neuroimaging is a definite need in cases which cannot be proved to be either Type 1 or 2. We recommend that patients who present with acute onset of diplopia and comitant esotropia receive a complete ophthalmologic and neurological examination and a careful history taken to rule out cyclic esotropia, paretic strabismus, and myasthenia gravis, any of which may also present acutely.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Hoyt CS, Good WV. Acute onset concomitant esotropia: When is it a sign of serious neurological disease? Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:498–01. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.5.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Noorden GK, Campos EC. Binocular vision and ocular motility: Theory and management of strabismus. 6th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2002. pp. 388–40. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kothari M. Clinical characteristics of spontaneous late onset acute comitant nonaccomodative esotropia in children. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:117–20. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.30705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dikici K, Cicik E, Akman C, Kendiroulu G, Tolun H. Cerebellar Astrocytoma presenting with acute esotropia in a 5 year-old girl. Int Ophthalmol. 2001;23:167–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1010676913684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbert ME, Meira D, Foroozan R, Edmond J, Phillips P. Double vision worth a double take. Surv Ophthalmol. 2006;51:587–91. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newman-Toker DE, Rizzo JF., 3rd Neuro-ophthalmic disease masquerading as benign strabismus. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2001;41:115–27. doi: 10.1097/00004397-200110000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rangwala LM, Liu GT. Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52:597–617. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parentin F, Marchetti F, Faleschini E, Tonini G, Pensiero S. Acute comitant esotropia secondary to idiopathic intracranial hypertension in a child receiving recombinant human growth hormone. Can J Ophthalmol. 2009;44:110–1. doi: 10.3129/i08-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein JH, Schneekloth BB. Spasm of the near reflex: A spectrum of anomalies. Surv Ophthalmol. 1996;40:269–78. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(96)82002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paul Chan RV, Trobe JD. Spasm of accommodation associated with closed head trauma. J Neuroophthalmol. 2002;22:15–7. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]