Abstract

Context:

Dexamethasone Posterior-Segment Drug Delivery System is a novel, biodegradable, sustained-release drug delivery system (OZURDEX®) for treatment of macular edema following retinal vein occlusion and posterior uveitis. However, its potential role in management of diabetic macular edema has not been reported yet.

Aim:

The aim was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of (OZURDEX®) in patients with recalcitrant diabetic macular edema (DME).

Setting and Design:

A retrospective, interventional case series from a tertiary eye care center in India is presented. Inclusion criteria comprised patients presenting with recalcitrant DME, 3 or more months after one or more treatments of macular laser photocoagulation and/or intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injections. Exclusion criteria included history of corticosteroid-responsive intraocular pressure (IOP) rise, cataract extraction, or other intraocular surgery within 3 months. The main outcome measure was visual acuity at 1 and 4 months after OZURDEX® injection. Secondary outcome measures included change in central macular thickness on Optical coherence tomography (OCT) and changes in IOP following intravitreal OZURDEX® implant. Of 18 eyes (17 patients) with recalcitrant diabetic macular edema that underwent OZURDEX® implant, three eyes (two patients) had follow-up of more than 3 months post-injection.

Results:

Mean age of patients was 56 years. Mean duration of diabetes mellitus was 16.6 years. Systemic control of DM was good as assessed by FBS/PPBS and HbA1c. The pre-operative mean central macular thickness was 744.3 μm and improved to 144 and 570 μm at months 1 and 4, respectively. Preoperative mean BCVA was 0.6 logMAR units and improved to 0.3 and 0.46 logMAR units at month 1 and 4, respectively. The mean follow-up was 4.3 months (range 4-5 months).

Conclusion:

OZURDEX® appears efficacious in management of recalcitrant diabetic macular edema. The results of the ongoing POSURDEX® study will elaborate these effects better.

Keywords: Dexamethasone, diabetes mellitus, diabetic macular edema, intravitreal implant, OZURDEX®

Introduction

Diabetic macular edema (DME) is the most common cause of reduced visual acuity in type 2 diabetes mellitus. DME can be either ischemic or exudative, based on the dominant underlying disease mechanism. In ischemic DME, the main problem is a reduction in blood flow to the macula which causes reduced central vision and swelling of the retinal tissues in this area.[1] In exudative DME, excessive leakage of fluid from the blood vessels around the macula results in thickening or swelling of the retina and a resultant reduction in central vision. In a patient with DME, it is usually a combination of both. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been implicated as a potential cause of vascular abnormalities seen in DME.[2] Corticosteroids have been shown to inhibit the expression of VEGF.[3–8] Additionally, corticosteroids prevent the release of prostaglandins, some of which have been identified as mediators of cystoid macular edema. Intravitreal injections of triamcinolone acetonide have produced benefits in patients with DME[9–13] but several adverse events like high intraocular pressures and cataract have been reported.[9] Dexamethasone, a potent corticosteroid, has been shown to suppress inflammation by inhibiting release of prostaglandins, preventing fibrin deposition, capillary leakage, and phagocytic migration of the inflammatory response.[14–16] By delivering a drug directly into the vitreous cavity, the blood-eye barriers are circumvented and intraocular therapeutic levels can be achieved with minimal risk of systemic toxicity. This route of administration typically results in a short half-life unless the drug can be delivered using a formulation capable of providing sustained release. Dexamethasone Posterior-Segment Drug Delivery System (DEX implant; OZURDEX®, Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA) is a novel, biodegradable, sustained-release drug delivery system recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of macular edema following retinal vein occlusion and posterior uveitis.[17] It is composed of biodegradable copolymer containing micronized dexamethasone. The drug-copolymer complex gradually releases the total dose of dexamethasone over a series of several months after insertion into the vitreous. This series evaluates the short-term results of OZURDEX® in patients with recalcitrant diabetic macular edema in terms of visual improvements, improvement in macular edema, and adverse effects.

Materials and Methods

In this retrospective, interventional series, three eyes of two patients with DME for a period ranging from 4-12 months were studied. Prior Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not required as this was a retrospective study. Inclusion criteria included patients with recalcitrant diabetic macular edema who met the following criteria: age older than 18 years, best corrected visual acuity of 0.3 logMAR units or worse, persistent clinically significant macular edema involving the center of the fovea 3 or more months after one or more treatments of focal macular laser photocoagulation and/or intravitreal anti-VEGF injections and ability to give informed consent. Exclusion criteria were a history of corticosteroid-responsive intraocular pressure (IOP) rise, cataract extraction, or other intraocular surgery within 3 months and any other laser treatment within 1 month (including YAG laser capsulotomy). After a detailed explanation of the risks and benefits of the injection and obtaining written informed consent, a comprehensive ophthalmic history was elicited from all patients. Clinical examination included best-corrected Snellen visual acuity, IOP measurement, anterior segment examination including evaluation of lens status, dilated fundus examination and optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the central macula showing thickness at baseline. Patients underwent Ozurdex® implant in operating room under topical anesthesia. All patients received topical ciprofloxacin 0.3% eye drops six times/day for 3 days prior to and 5 days post-injection and were examined on day 1 for visual acuity, anterior chamber reaction, IOP and fundus examination. The recommended technique for intraocular injection of the implant is described. The patient is prepared in operating room with the same standards as followed for intraocular procedures. Maintaining aseptic technique, the cap is carefully removed from the applicator. The safety tab is pulled straight off the applicator without twisting or flexing it. The long axis of applicator is held parallel to limbus and sclera is engaged at an oblique angle with bevel of the needle up to create a shelved scleral path, 4 mm away from limbus. The needle-tip is advanced within the sclera for about 1 mm, then redirected towards the center of the eye and advanced until the penetration of sclera is completed and vitreous cavity is entered. The needle should not be advanced past the point where the sleeve touches the conjunctiva. The actuator button is slowly depressed until an audible click is noted. Before withdrawing the applicator from the eye, one makes sure that the actuator button is fully depressed and has locked flush with the applicator surface. The needle is removed in the same direction as while entering the vitreous cavity. Fundus is carefully examined.

All patients were examined on post-operative day 1 for visual acuity, anterior chamber reaction, intraocular pressure (IOP), and fundus evaluation by indirect ophthalmoscopy. Complete ocular examination and optical coherence tomography (OCT; 3D OCT-1000, Topcon Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was performed at periodic intervals, thereafter. The main outcome measure was visual acuity at 1 and 4 months after injection. Secondary outcome measures included change in central macular thickness on OCT, changes in IOP, and development of any side effects resulting from the intravitreal injection of OZURDEX® implant. Out of 18 eyes (17 patients) with recalcitrant diabetic macular edema that underwent OZURDEX® implant, three eyes (two patients) had follow-up of more than 3 months postinjection. The mean age of the patients was 56 years (range 46-61 years).

Results

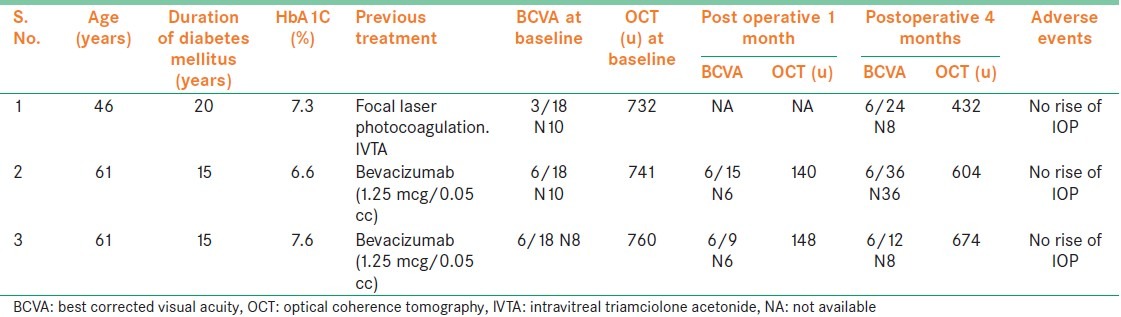

The mean duration of diabetes mellitus was 16.6 years. The HbA1c levels are shown in Table 1. Out of three eyes, one had received intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide twice in last 6 months, with the last injection given 3 months back. Two eyes had received intravitreal injection bevacizumab (1.25 mcg/0.05 cc) 6 months back with macular grid laser done 3 months back. The mean baseline IOP was 17 mmHg (range 14- -18). One eye was pseudophakic whereas others were phakic with nuclear sclerosis. The last follow-up was up till 4 months following Ozurdex® implant. Preoperative mean central macular thickness was 744.33 μm which improved to 144 μm at month 1 and increased to 570 microns at month 4. Preoperative mean best corrected visual acuity was 0.6 logMAR units which improved to 0.3 logMAR units at month 1 and 0.46 logMAR units at month 4. Table 1, Figures 1 and 2 summarize the cases with preinjection and postinjection visual acuities and foveal thickness. No rise of IOP occurred in any of the three eyes. None of eyes showed progression of cataract from the baseline.

Table 1.

Clinical features and follow-up of patients undergoing treatment

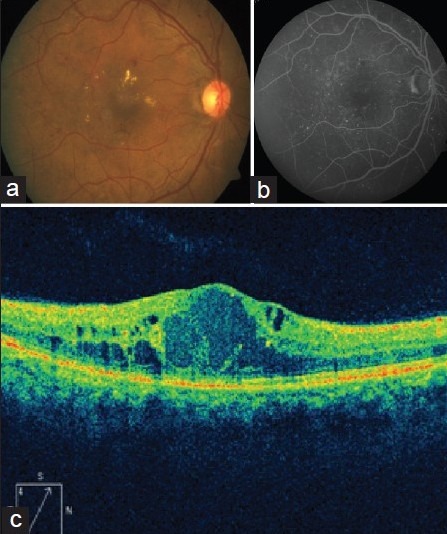

Figure 1.

Case 1, baseline. (a) color fundus photo of right eye reveals multiple retinal hemorrhages, hard exudates and increased macular thickness. (b) arteriovenous phase of fluorescein angiography (FA) reveals multiple areas of pinpoint hyperfluorescence corresponding to leaking retinal microaneurysms. (c) OCT scan shows increased macular thickness with multiple intraretinal cystoid spaces (536 μm)

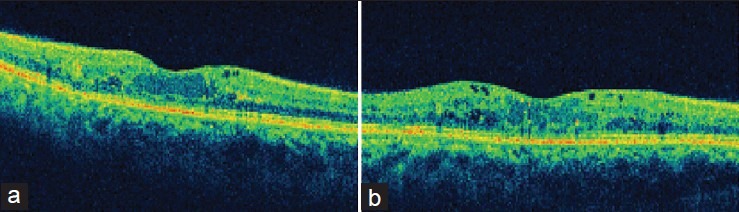

Figure 2.

Case 1. (a) OCT scan at 1 month follow-up shows near-complete resolution of macular edema and restored foveal contour (228 μm). (b) OCT scan at 3-month follow-up shows rebound macular edema with increased macular thickness, intraretinal cystoid spaces (340 μm)

Discussion

Management of diabetic macular edema that is refractory to laser photocoagulation, anti-VEGF injections or intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide (IVTA) is challenging and the treatment options are limited. The recent randomized, controlled trials have shown that laser photocoagulation,[18] intravitreal injections of antivascular endothelial growth factor agent ranibizumab[19] and corticosteroids triamcinolone acetonide[9,10] have been useful in treatment of diabetic macular edema. These studies also show, however, that repeated treatments are often required to control macula edema, prevent vision loss, and increase the chance of visual improvement. Ozurdex® has been recently approved by Drug Controller General of India (DCGI) for the treatment of macular edema following retinal vein occlusion (RVO). A recent study in eyes with persistent macular edema demonstrated that dexamethasone implant produced improvements in visual acuity, macular thickness, and fluorescein leakage that were sustained for up to 6 months. The study included eyes with macular edema due to a variety of causes, including diabetic retinopathy, retinal vein occlusion, uveitis, or Irvine-Gass syndrome.[17] A subgroup analysis of the key efficacy findings for eyes with different causes of macular edema found that the results for each group were generally consistent with those for the entire study population.

In our study it was seen that after OZURDEX® implant there was significant reduction in central macular thickness compared to baseline levels at month 1. The maximum reduction in macular thickness was seen at month 1 followed by re-appearance of macular edema clinically significant macular edema at month 4. This showed that the peak effect of the drug was in between 1 and 4 months, which is significantly different compared to eyes with macular edema secondary to CRVO or BRVO where the drug effects lasts for 6 months as reported in the study.[17] The mean post-injection BCVA at month 1 showed improvement in all eyes but was not as significant as the reduction in central macular thickness at the same timeline. This could be explained by the fact that these eyes had chronic, recalcitrant diabetic macular edema and diabetes mellitus since more than 15 years that could have lead to irreversible changes in the macula.

Rise in intraocular pressure is a known side effect after intraocular corticosteroids injections. In our study, out of three eyes none had a rise of intraocular pressure. Studies have shown that percentage of eyes receiving triamcinolone (4 mg) have higher risks of IOP elevation more than or equal to 10 mm Hg (8.9%) compared to sustained release of dexamethasone (0.9%) in patients with macular edema secondary to RVO over the course of 12 months.[20] None of the eyes had significant cataract progression which could have caused significant reduction in visual acuity at 4 months compared to baseline level. In patients with macular edema secondary to RVO who received OZURDEX® injection, only 1.3% of phakic eyes underwent cataract surgery over the course of 12 months.[21]

Finally, any beneficial effect on visual acuity and reduction of DME on OCT seen initially at month 3, tends to wane off by month 4. Since the effect of OZURDEX appears transient, repeated injections may be necessary to maintain visual improvement. Whether repeat injections will result in same amount of visual improvement or reduction in macular edema would be explained by more studies with longer follow-up.

In summary, these short-term results suggest that OZURDEX® may be beneficial in treatment of refractory diabetic macular edema. Furthermore, a 4-month dosing interval could probably be a better option than 6-monthly injections This observation may very well be addressed from the results of a currently ongoing, prospective, randomized clinical trial assessing OZURDEX® for diabetic macular edema.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Pelzek C, Lim JI. Diabetic macular edema: Review and update. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2002;15:555–63. doi: 10.1016/s0896-1549(02)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Funatsu H, Yamashita H, Noma H, Mimura T, Yamashita T, Hori S. Increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin-6 in the aqueous humor of diabetics with macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:70–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antonetti DA, Barber AJ, Khin S, Lieth E, Tarbell JM, Gardner TW Penn state retina research group. Vascular permeability in experimental diabetes is associated with reduced endothelial occludin content: Vascular endothelial growth factor decreases occludin in retinal endothelial cells. Diabetes. 1998;47:1953–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.12.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leopold IH. Nonsteroidal and steroidal anti-inflammatory agents. In: Sears M, Tarkkanen A, editors. Surgical pharmacology of the eye. New York NY: Raven Press; 1985. pp. 83–133. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nauck M, Karakiulakis G, Perruchoud A, Papakonstantinou E, Roth M. Corticosteroids inhibit the expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor gene in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;341:309–15. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01464-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tennant JL. Cystoid maculopathy: 125 prostaglandins in ophthalmology. In: Emery JM, editor. Current concepts in cataract surgery: Selected proceedings of the fifth biennial cataract surgical congress. St Louis MO: CV Mosby; 1978. pp. 360–2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antonetti DA, Wolpert EB, DeMaio L, Harhaj NS, Scaduto RC., Jr Hydrocortisone decreases retinal endothelial cell water and solute flux coincident with increased content and decreased phosphorylation of occludin. J Neurochem. 2002;80:667–77. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edelman JL, Lutz D, Castro MR. Corticosteroids inhibit VEGF-induced vascular leakage in a rabbit model of blood-retinal and blood aqueous barrier breakdown. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80:249–58. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. A randomized trial comparing intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide and focal/grid photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1447–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonas JB, Kreissig I, Sofker A, Degenring RF. Intravitreal injection of triamcinolone for diffuse diabetic macular edema. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sutter FKP, Simpson JM, Gillies MC. Intravitreal triamcinolone for diabetic macular edema that persists after laser treatment: Three-month efficacy and safety results of a prospective, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:2044–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillies MC, Sutter FK, Simpson JM, Larsson J, Ali H, Zhu M. Intravitreal triamcinolone for refractory diabetic macular edema: Two-year results of a doublemasked, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1533–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martidis A, Duker JS, Greenberg PB, Rogers AH, Puliafito CA, Reichel E, et al. Intravitreal triamcinolone for refractory diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:920–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)00975-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nabih M, Peyman GA, Tawakol ME, Naguib K. Toxicity of high-dose intravitreal dexamethasone. Int Ophthalmol. 1991;15:233–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00171025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwak HW, D’Amico DJ. Evaluation of the retinal toxicity and pharmacokinetics of dexamethasone after intravitreal injection. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:259–66. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080140115038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maxwell DP Jr, Brent BD, Diamond JG, Wu L. Effect of intravitreal dexamethasone on ocular histopathology in a rabbit model of endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1370–5. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuppermann BD, Blumenkranz MS, Haller JA, Williams GA, Weinberg DV, Chou C, et al. Dexamethasone DDS Phase II Study Group. Randomized controlled study of an intravitreous dexamethasone drug delivery system in patients with persistent macular edema. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:309–17. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neubauer AS, Ulbig MW. Laser treatment in diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmologica. 2007;221:95–102. doi: 10.1159/000098254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen QD, Shah SM, Khwaja AA, Channa R, Hatef E, Do DV, et al. Two-year outcomes of the ranibizumab for edema of the macula in diabetes (READ-2) study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:2146–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haller JA, Bandello F, Belfort R, Jr, Blumenkranz MS, Gillies M, Heier J, et al. Randomized, sham-controlled trial of dexamethasone intravitreal implant in patients with macular edema due to retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1134–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ip MS, Scott IU, VanVeldhuisen PC, Oden NL, Blodi BA, Fisher M, et al. SCORE study research group. A randomized trial comparing the efficacy and safety of intravitreal triamcinolone with observation to treat vision loss associated with macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion: The standard care vs corticosteroid for retinal vein occlusion (SCORE) study report 5. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1101–14. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]