Abstract

Background

Mitral valve disease is often accompanied by concomitant tricuspid valve disease. The purpose of this study was to determine the influence of performing tricuspid procedures in the setting of mitral valve surgery within a multi-institutional patient population.

Methods

From 2001–2008, 5,495 mitral valve operations were performed at 17 different statewide centers. Patients underwent either mitral valve alone (MV alone, n=5,062, age=63.4±13.0 years) or mitral + tricuspid valve operations (MV+TV, n=433, age=64.0±14.2 years). Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to assess the influence of concomitant tricuspid procedures on operative mortality and the composite incidence of major complications.

Results

Patients undergoing MV+TV were more commonly female (62.7% vs. 45.5%, p<0.001), had higher rates of heart failure (73.7% vs. 50.9%, p<0.001), and more frequently underwent reoperations (17.1% vs. 7.4%, p<0.001) compared to MV alone patients. Other patient characteristics, including preoperative endocarditis (8.5% vs. 8.2%, p=0.78), were similar between groups. Mitral replacement (63.5%) was more common than repair (36.5%, p<0.001) in MV+TV operations, and MV+TV operations incurred longer median cardiopulmonary bypass (181 min. vs. 149 min, p<0.001) times. Unadjusted operative mortality (6.0% vs. 10.4%, p=0.001) and postoperative complications were higher following MV+TV compared to MV alone. Importantly, after risk adjustment, performance of concomitant tricuspid valve procedures proved an independent predictor of operative mortality (OR=1.50, p=0.03) and major complications (OR=1.39, p=0.004).

Conclusions

Concomitant tricuspid surgery is a proxy for more advanced valve disease. Compared to mitral operations alone, simultaneous mitral-tricuspid valve operations are associated with elevated morbidity and mortality even after risk adjustment. This elevated risk should be considered during preoperative patient risk stratification.

Keywords: Mitral, Tricuspid, Valve, Risk Adjustment, Mortality, Outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Mitral valve disease is often accompanied by concomitant tricuspid valve disease, and the outcome of concomitant tricuspid valve correction at the time of mitral valve procedure has been debated. The most common indication for tricuspid valve intervention is tricuspid regurgitation (TR), and the presence of significant TR has been reported to be an important prognostic indicator of outcomes following mitral valve surgery [1, 2]. The development of late moderate to severe TR after mitral valve surgery has also been documented to occur with an incidence of 7– 16% in some series [3, 4]. As a result, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease specifically recommend (Class I) surgical correction of severe TR at the time of mitral valve repair or replacement [5].

The Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative (VCSQI) is a voluntary consortium of 17 different collaborating cardiac surgical centers, both academic and private, within the Commonwealth of Virginia that exchange and compare de-identified patient data on a quarterly basis with the objective of improving cardiac surgical care, quality and costs. Collectively, the VCSQI centers perform approximately 99% of the Commonwealth’s cardiac operations, and each center individually contributes patient data to the national Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the influence of concomitant tricuspid procedures at the time of mitral valve surgery within a large, current, multi-institutional patient population. We hypothesized that the addition of a tricuspid valve procedure would add significant operative risk compared to isolated mitral valve operation due to more advanced valve disease and an inherently sicker patient population.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

The University of Virginia Institutional Review Board (IRB) exempted this study from formal review as it is a secondary analysis of the VCSQI data registry with the absence of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) patient identifiers and because the data is collected for quality analysis and purposes other than research.

De-identified patient level data was obtained from the VCSQI database for the years 2003–2008. All records included patients undergoing mitral valve procedures with and without concomitant tricuspid valve procedures. Patient records were stratified by operation type: MV Only and MV+TV. All valve procedures represent standard surgical approaches to the mitral and tricuspid valve and standard STS variable definitions were utilized [6]. Patient preoperative risk was assessed by the calculated STS predicted risk of mortality (PROM) for each patient where available.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of interest included risk-adjusted associations between mortality and morbidity and the performance of concomitant tricuspid valve procedures during mitral valve operations. Secondary outcomes included observed differences in patient morbidity, mortality and resource utilization. Operative mortality was defined as all patient deaths occurring during hospitalization as well those within 30 days of the date of surgery despite discharge status. A composite outcome of major complications was utilized as a proxy for major morbidity and included the incidence of deep sternal wound infection, postoperative stroke, renal failure, prolonged ventilation, pneumonia, and need for reoperation. Standard STS definitions for postoperative events and complications were utilized, including prolonged ventilation (>24 hours of mechanical ventilation), presence of any new onset atrial fibrillation, and renal failure (increase in serum creatinine level > 2.0 or 2× the most recent preoperative creatinine level) [6].

Statistical Analysis

All study outcomes and data comparisons were established a priori before data collection. Missing data for all variables of interest underwent sequential case-wise deletion to obtain a complete dataset for subsequent analysis. Less than 5% of the original patient population underwent case-wise deletion at the beginning of data extraction from the VCSQI. Patients removed from the study dataset were missing mortality data, age, gender, or type of valve operation.

Descriptive, univariate statistics included either Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s Exact test for categorical variables and either independent sample single factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) for parametric data comparisons or the Mann Whitney U test for non-parametric data comparisons. Continuous variables are expressed as either mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median [interquartile range] depending upon overall variable distribution. Standard statistical signifiance was considered for all two-tailed p-values <0.05.

Hierarchical multiple logistic regression analysis was used to estimate confounderadjusted associations between various patient and operative factors and observed patient morbidity (major complications) and operative mortality. To account for inter-hospital variance, clustering at the hospital level was considered in the hierarchical structure of each logistic regression model. Model covariates were selected a priori and included patient age, gender, history of infective endocarditis, preoperative renal failure, stroke, non-elective operative status, NYHA class IV functional status, reoperation, and aortic cross clamp time. In each model, aortic cross clamp time was included as a surrogate variable to account for the estimated effects of surgeon experience as well as degree of valve pathology. Confounder adjusted measures of association are reported as odds ratios (OR) with a 95% confidence interval. Model performance was assessed using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristics curve (AUC), while the Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used to verify model calibration across deciles of observed and predicted risk.

Predictive Analytics SoftWare (PASW) with complex sampling module software, version 18.0.0 (IBM Corporation, Somers, NY) was used for all data manipulation and statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Operative Features for Mitral ± Tricuspid Valve Operations

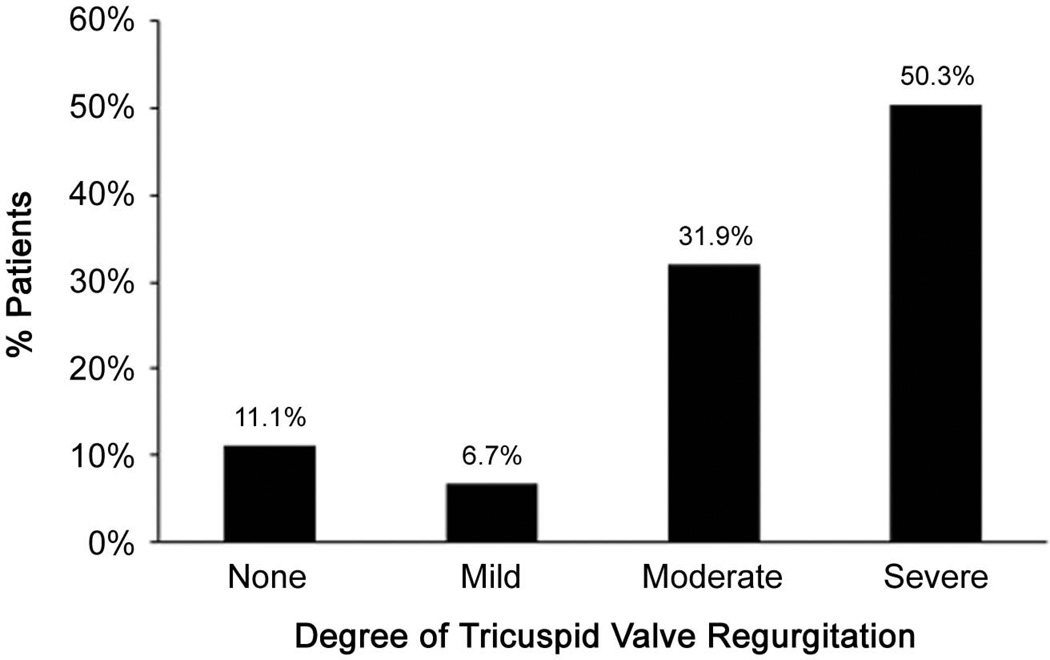

Table 1 reports patient characteristics and operative features for all patients stratified by both mitral and tricuspid valve procedure type. Among those undergoing MV Only, mitral valve replacement (MVR) was performed in 2,262 (44.7%) patients, while mitral valve repair (MV repair) was performed in 2,800 (55.3%) patients. MVR was more commonly performed in females. MVR patients had a higher prevalence of preoperative risk and longer aortic cross clamp times compared to MV repair. Among MV+TV operations, performance of TV repair (94.2%) was far more common than performance of tricuspid valve replacement (TVR, 5.8%). MV+TVR patients, however, represented a higher risk patient population compared to MV+TV Repair patients. Further, the performance of MVR was also more common among those undergoing MV+TVR operations, and these patients accrued longer pump times than MV+TV Repair patients. Severe tricuspid regurgitation (TR) was the most common indication for TV procedure. The degree of TR among patients undergoing tricuspid procedures is depicted in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and operative features for mitral valve ± tricuspid valve operations.

| Variable | MV Only (n=5,062) |

MV+TV (n=433) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVR (n=2,262) |

MV Repair (n=2,800) |

MV+TVR (n=25) |

MV+TV Repair (n=408) |

|

| PREOPERATIVE | ||||

| Patient Age | 64.1±13.1 | 62.9±12.7 | 58.0±15.5 | 64.4±14.0 |

| Sex (Female) | 53.5% | 39.1% | 68.0% | 67.2% |

| Hypertension | 64.7% | 64.1% | 44.0% | 62.5% |

| Peripheral Arterial Disease | 11.0% | 9.1% | 4.0% | 8.6% |

| Stroke | 10.1% | 6.5% | 24.0% | 7.8% |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 23.7% | 23.6% | 20.0% | 20.8% |

| Dyslipidemia | 49.8% | 51.4% | 28.0% | 42.9% |

| Heart Failure | 57.3% | 45.9% | 68.0% | 74.0% |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.7% | 0.8% | 8.0% | 1.5% |

| NYHA Class | ||||

| Class III | 43.9% | 38.9% | 31.8% | 44.6% |

| Class IV | 24.4% | 19.6% | 45.5% | 29.2% |

| Infective Endocarditis | 12.1% | 5.0% | 28.0% | 7.4% |

| Renal Failure | 9.3% | 6.7% | 16.0% | 10.0% |

| Renal Failure (Hemodialysis) | 5.1% | 2.8% | 8.0% | 5.1% |

| Previous CABG | 8.9% | 5.1% | 16.0% | 7.8% |

| Previous Valve Procedure | 14.5% | 1.7% | 16.0% | 17.2% |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 55.0 [15.0] | 50.0 [25.0] | 55.0 [19.8] | 55.0 [20.0] |

| Mean Pulmonary Artery Pressure (mmHg) | 24.0 [14.0] | 30.0 [17.0] | 22.5 [30.0] | 32.0 [18.0] |

| STS Predicted Risk Mortality | 0.06 [0.09] | 0.02 [0.05] | - | - |

| OPERATIVE | ||||

| Mitral Valve Replacement | 100.0% | - | 72.0% | 63.0% |

| Mitral Valve Repair | - | 100.0% | 28.0% | 37.0% |

| Tricuspid Valve Replacement | - | - | 100.0% | - |

| Tricuspid Valve Repair | - | - | - | 100.0% |

| Annuloplasty Only | - | - | - | 86.4% |

| Reconstruction with Annuloplasty | - | - | - | 6.0% |

| Reconstruction Only | - | - | - | 1.8% |

| Elective status | 60.4% | 68.6% | 44.0% | 64.7% |

| Urgent status | 35.4% | 30.1% | 48.0% | 33.1% |

| Emergent status | 4.2% | 1.4% | 8.0% | 2.2% |

| Aortic Cross Clamp Time (min) | 115.0 [70.0] | 103.0 [58.0] | 160.5 [111.0] | 125.0 [63.0] |

Figure 1.

Degree of tricuspid valve regurgitation among those undergoing concomitant tricuspid valve procedures.

Unadjusted Outcomes Following Mitral ± Tricuspid Valve Operations

The incidence of postoperative complications as well as differences in postoperative length of stay for patients undergoing MV Only vs. MV+TV operations is presented in Table 2. Overall, MV+TV patients demonstrated higher observed mortality and morbidity compared to MV Only patients. Moreover, MV+TV operations were associated with a higher composite incidence of major complications, including prolonged ventilation, renal failure, and the onset of new hemodialysis. Postoperative length of stay was 2 days longer for those undergoing MV+TV operations. Performance of MVR and TVR was not surprisingly associated with higher mortality and morbidity compared to respective valve repairs. Compared to MV Repair, operative mortality was 2 fold higher for MVR within the MV Only cohort, and MVR had a higher major complication rate including prolonged ventilation, renal failure, and hemodialysis. Within the MV+TV study cohort, those undergoing MV+TVR encountered higher mortality and an increased incidence of almost all postoperative complications compared to MV+TV Repair; however, many of these comparisons failed to achieve statistical significance due to the infrequent performance of concomitant tricuspid valve replacement.

Table 2.

Postoperative outcomes for mitral valve ± tricuspid valve operations.

| Outcome | MV Only (n=5,062) |

MV+TV (n=433) |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVR (n=2,262) |

MV Repair (n=2,800) |

MV+TVR (n=25) |

MV+TV Repair (n=408) |

||

| Operative Mortality | 8.6% | 4.0% | 16.0% | 10.0% | <0.001 |

| Major Complication | 34.0% | 22.6% | 56.0% | 37.0% | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 2.2% | 2.2% | 4.0% | 1.0% | 0.37 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 0.2% | 0.2% | 4.0% | - | 0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 6.9% | 4.2% | 16.0% | 7.8% | <0.001 |

| Prolonged Ventilation | 24.4% | 15.3% | 52.0% | 27.5% | <0.001 |

| Renal Failure | 10.5% | 5.4% | 20.0% | 10.8% | <0.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 5.7% | 2.3% | 4.0% | 6.1% | <0.001 |

| Postoperative Length of Stay (Days) | 8.0 [7.0] | 7.0 [4.0] | 11.0 [16.0] | 9.0 [7.0] | <0.001 |

Concomitant Tricuspid Procedures Associated with Increased Morbidity and Mortality

Risk adjusted associations between operation type and mortality and morbidity are displayed in Table 3. Among the covariates entered into each risk-adjustment model, nonelective operative status (OR=2.73), active infective endocarditis (OR=2.09), performance of MV+TV Repair (OR=2.06), preoperative renal failure (OR=2.02), advanced NYHA class (OR=1.86), performance of MVR (OR=1.61), increasing aortic cross clamp time (OR=1.008) and patient age (OR=1.03) were all significant independent predictors of operative mortality (all p<0.05). Within the morbidity model, similar measures of association were observed between the aforementioned risk factors and the composite incidence of major complications. Importantly, the performance of MV+TVR alone did not achieve statistical significance in each model due to the relatively low frequency of concomitant TVR. However, when performance of any concomitant TV procedure (TVR or TV Repair) was considered, an increase in the adjusted odds of mortality (OR=1.50, p=0.03) and major complications by (OR=1.39, p=0.004) was observed.

Table 3.

Risk-adjusted associations between operation type and operative mortality and major complications (n=5,495).

| Covariate | Operative Mortality Model |

p | Major Complications Model |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitral Valve Repair (Reference) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Mitral Valve Replacement | 1.61 [1.24–2.09] | <0.001 | 1.39 [1.21–1.60] | <0.001 |

| Mitral Valve + Tricuspid Replacement | 2.21 [0.69–7.11] | 0.18 | 2.32 [0.97–5.54] | 0.05 |

| Mitral Valve + Tricuspid Repair | 2.06 [1.38–3.07] | <0.001 | 1.63 [1.28–2.06] | <0.001 |

Results reported as adjusted Odds Ratios [95% confidence Interval]. Area Under Receiver Operative Curve=0.77 and 0.71, respectively.

The statistical performance of each logistic regression model achieved adequate discrimination with an AUC of 0.77 and 0.74 for the operative mortality model and major complications model, respectively. The calibration of each model was adequate across deciles of observed risk as reflected by Hosmer-Lemeshow p<0.05 for both models.

COMMENT

The present study reports the influence of concomitant tricuspid valve procedures during mitral valve operations within a large, multi-institutional cohort of cardiac surgery patients. In this contemporary analysis, simultaneous mitral-tricuspid valve operations was associated with increased unadjusted morbidity (38% vs. 28%, p<0.001) and mortality (10% vs. 6%, p=0.001) as well as longer postoperative lengths of stay compared to mitral operations alone. MV+TV operations also encountered significantly higher incidence of postoperative prolonged ventilation, renal failure and new onset hemodialysis. The detrimental impact of concomitant TV operations on mortality and morbidity was even more apparent following risk-adjustment for the confounding influence of several established risk factors for mitral valve operations. Concomitant TV procedures were associated with a 50% and 39% increase in the adjusted odds of operative mortality and major complications respectively (both p<0.05) compared to the performance of MV Only procedures. Moreover, both mitral and tricuspid valve replacements demonstrated increased mortality and morbidity compared to valve repair procedures, and the performance of MVR conferred a 61% and 39% increase in the risk-adjusted odds of mortality and major complications (both p<0.001). To our knowledge, these data represent the largest series to specifically report upon the increase in operative risk associated with the performance of concomitant tricuspid valve procedures during mitral valve operations.

Little has been reported on outcomes following combined mitral and tricuspid valve surgery. Most reports are single-institution series, while large, multi-institutional, population-based studies are limited. Reported results of combined procedures have demonstrated worse outcomes compared to those documented for isolated mitral procedures. In a recent series by Bernal and colleagues, the early mortality for combined mitral and tricuspid procedures in 153 patients with rheumatic heart disease was 6%, while late mortality was 60% with a median follow-up of 16 years [7]. With respect to functional tricuspid valve regurgitation, Kay et al documented a mortality of 14% in 156 patients, and we have previously reported mortality rates of 8.9% in a cohort of 168 patients [8, 9].

These results are in contrast to reported outcomes for single mitral valve repair or replacement operations. Studies directly comparing single mitral valve repair and replacement have generally demonstrated that operative mortality and long-term survival favor mitral repair over replacement [10, 11]. Recent reports from the STS national database demonstrate operative mortality for isolated mitral repair is 1.7% compared to 5.9% for mitral replacement [12]. Thourani et al. [11], recently reported 4.3% in-hospital mortality for mitral repair versus 6.9% for replacements (p=0.049) as well as a 10-year survival advantage for mitral repairs (62% vs. 46%) in a propensity matched study of 625 MV repairs and 625 replacements.

Resource utilization is also greater for combined mitral-tricuspid valve operations. Several prior series have documented longer postoperative hospital stays for patients undergoing mitral replacement compared to repair operations [10, 11, 13]. In a recent report from the national STS database of over 58,000 mitral valve operations median postoperative length of stay was longer for mitral valve replacement (7.0 days) versus repair (6.0 days, p<0.001) [13]. These trends are consistent with our report of shorter postoperative lengths of stay for mitral repair (7.0 days) compared to replacement (8.0, p<0.001) among MV Only operations. Similarly, the longer median lengths of stay (9 vs. 7 days, p<0.001) observed for MV+TV operations compared to MV Only (9 vs. 7 days, p<0.001) and those for TVR versus TV Repair (11 vs. 9 days, p<0.001) are in agreement with results reported elsewhere [14].

The reported results have important clinical implications. In an era of increasingly complex operations and patients, these results provide clinical estimates of the adjusted impact of performance of concomitant tricuspid valve surgery at the time of mitral repair or replacement. This is particularly relevant since the STS risk model does not calculate a PROM for patients undergoing tricuspid valve disease. Moreover, these results are from a very large, multiinstitutional cohort of patients, thus providing a report of outcomes that are much more generalizable than those of other small, single-institutional series. Further, the use of hierarchical structured multivariable regression models with performance indices that demonstrate adequate discrimination between dependent outcomes, demonstrate that the granularity of the analyzed data is appropriately controlled for and that the estimated effects of the performance of concomitant tricuspid operations are adequate. These results can assist clinicians in their preoperative assessment of patient operative risk and highlight the importance of discussing the increased risk of performance of concomitant tricuspid valve surgery at the time of mitral repair or replacement with patients and their families.

The prevalence of tricuspid regurgitation (TR) and performance of tricuspid repair or replacement in this series is noteworthy. Among the 11% of patient with no TR, the indication for a concomitant tricuspid operation was tricuspid stenosis. From the data available for analysis, we were unable to exactly determine the rationale or indication for valve repair in those with mild TR. However, the degree of TR can be variable as TR is very dynamic. It is certainly possible that any given patients’ mild TR might have been more significant preoperatively and clinically compared to what was documented intraoperatively when patients may be dehydrated and under general anesthesia, rendering the TR less when recorded in the database. Nevertheless, considering that nearly 90% of MV+TV operations were performed on patients with moderate to severe TR, we believe that these results should not be extrapolated to reflect the influence of concomitant TV surgery in cases of mild functional TR, and is not recommended by current American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines [5].

The finding of a non-significant association between reoperation and mortality deserves further discussion. While reoperations have historically placed patients at increased preoperative risk, we were not especially surprised by the results of the present findings as increasing literature has demonstrated improved outcomes for mitral valve reoperations with little to no difference in outcomes reported for primary and reoperations [13, 15]. Similar improvements in outcomes for aortic valve operations have also been reported [16], further suggesting that the influence of reoperative status alone is not as significant of a risk factor for valve operations as it may have been in the past.

The present study has limitations. First, the influence of selection bias for the performance of concomitant tricuspid valve procedure, and type of valve procedure (repair versus replacement) cannot be fully accounted for in these analyses. Second, the large heterogeneous patient population with a relatively high frequency of mitral and tricuspid valve replacements may have served to impact the observed incidence rates of postoperative events; however, the use of multiple regression modeling techniques attempted to account for confounding between study groups. Secondary analysis of the VCSQI data registry and STS data limited the performed analyses to de-identified data, which did not allow for further investigation of certain data, including type of mitral valve repair technique beyond the performance of reconstruction or annuloplasty, valve or annulus morphology and structural integrity, precise underlying disease-specific valve etiology, and changes to ventricular mass and/or function over time. These limitations have been noted in other large series utilizing nationwide STS cardiac valve data [13, 17], and we emphasize the importance of right ventricular status in the preoperative and operative assessment of patients with concomitant mitral and tricuspid disease. Regarding surgeon experience, although we were unable to directly assess the effect of surgeon experience in this series, we attempted to account for this confounding influence in our analyses through the surrogate influence of aortic cross clamp. While we advocate performance of mitral and tricuspid operations by experienced, high volume surgeons, we recognize that performance of these operations by surgeons with variable experience exists within the United States and is not likely to change. All analyses were limited to short-term, operative outcomes, and intermediate or long-term follow-up data were not available. The disproportionate prevalence of tricuspid replacement to repairs limited the statistical ability to more precisely assess differences in these patient populations. Finally, the potential for unrecognized miscoding of data must also be considered in any secondary analysis of a data registry.

Conclusions

Concomitant tricuspid surgery is a proxy for more advanced heart and valve disease. Compared to mitral operations alone, simultaneous mitral-tricuspid valve operations are associated with elevated morbidity and mortality even after risk adjustment. Importantly, other risk factors such as advanced age and urgency of operation more strongly influence mortality and morbidity risk. The increased risk of combined mitral-tricuspid procedures should be considered during preoperative patient risk stratification and evaluation. Future prospective clinical trials are needed to determine the clinical benefit of addition of tricuspid valve repair in cases of mild or moderate tricuspid regurgitation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative and George J. Stukenborg PhD for his statistical mentorship in this study.

This study was supported by Award Number 2T32HL007849-11A1 (ILK) from the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute and the Thoracic Surgery Foundation for Research and Education Research Grant (GA).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at 58th Annual Meeting of the Southern Thoracic Surgical Association, San Antonio, TX, November 11, 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Braunwald NS, Ross J, Jr., Morrow AG. Conservative management of tricuspid regurgitation in patients undergoing mitral valve replacement. Circulation. 1967;35(4 Suppl):I63–I69. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.35.4s1.i-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nath J, Foster E, Heidenreich PA. Impact of tricuspid regurgitation on long-term survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(3):405–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuyama K, Matsumoto M, Sugita T, Nishizawa J, Tokuda Y, Matsuo T. Predictors of residual tricuspid regurgitation after mitral valve surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75(6):1826–1828. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song H, Kim MJ, Chung CH, Choo SJ, Song MG, Song JM, Kang DH, Lee JW, Song JK. Factors associated with development of late significant tricuspid regurgitation after successful left-sided valve surgery. Heart. 2009;95(11):931–936. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.152793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, de Leon AC, Jr, Faxon DP, Freed MD, Gaasch WH, Lytle BW, Nishimura RA, O'Gara PT, O'Rourke RA, Otto CM, Shah PM, Shanewise JS. 2008 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1998 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease). Endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(13):e1–e142. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database. STS Adult Cardiac Data Specifications, Version 2.61. 2007 Aug 24; Available at ( http://www.sts.org/documents/pdf/AdultCVDataSpecifications2.61.pdf)

- 7.Bernal JM, Ponton A, Diaz B, Llorca J, Garcia I, Sarralde JA, Gutierrez-Morlote J, Perez-Negueruela C, Revuelta JM. Combined mitral and tricuspid valve repair in rheumatic valve disease: fewer reoperations with prosthetic ring annuloplasty. Circulation. 2010;121(17):1934–1940. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.894873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kay GL, Morita S, Mendez M, Zubiate P, Kay JH. Tricuspid regurgitation associated with mitral valve disease: repair and replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989;48(3 Suppl):S93–S95. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(89)90656-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ailawadi G, Lapar DJ, Swenson BR, Siefert SA, Lau C, Kern JA, Peeler BB, Littlewood KE, Kron IL. Model for end-stage liver disease predicts mortality for tricuspid valve surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(5):1460–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.01.043. discussion 67-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ailawadi G, Swenson BR, Girotti ME, Gazoni LM, Peeler BB, Kern JA, Fedoruk LM, Kron IL. Is mitral valve repair superior to replacement in elderly patients? Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(1):77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.03.020. discussion 86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thourani VH, Weintraub WS, Guyton RA, Jones EL, Williams WH, Elkabbani S, Craver JM. Outcomes and long-term survival for patients undergoing mitral valve repair versus replacement: effect of age and concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting. Circulation. 2003;108(3):298–304. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000079169.15862.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Adult Cardiac Surgery Database. Society of Thoracic Surgeons. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gammie JS, Sheng S, Griffith BP, Peterson ED, Rankin JS, O'Brien SM, Brown JM. Trends in mitral valve surgery in the United States: results from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(5):1431–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.01.064. discussion 37-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh SK, Tang GH, Maganti MD, Armstrong S, Williams WG, David TE, Borger MA. Midterm outcomes of tricuspid valve repair versus replacement for organic tricuspid disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82(5):1735–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.06.016. discussion 41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potter DD, Sundt TM, 3rd, Zehr KJ, Dearani JA, Daly RC, Mullany CJ, McGregor CG, Puga FJ, Schaff HV, Orszulak TA. Risk of repeat mitral valve replacement for failed mitral valve prostheses. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(1):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.02.014. discussion 67-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaPar DJ, Yang Z, Stukenborg GJ, Peeler BB, Kern JA, Kron IL, Ailawadi G. Outcomes of reoperative aortic valve replacement after previous sternotomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139(2):263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gammie JS, Zhao Y, Peterson ED, O'Brien SM, Rankin JS, Griffith BP. J. Maxwell Chamberlain Memorial Paper for adult cardiac surgery. Less-invasive mitral valve operations: trends and outcomes from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(5):1401–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.05.055. 10 e1; discussion 08-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]