Abstract

Premature ejaculation (PE) is a common male sexual disorder which is associated with substantial personal and interpersonal negative psychological consequences. Pharmacotherapy of PE with off-label antidepressant selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) is common, effective and safe. Development and regulatory approval of drugs specifically for the treatment of PE will reduce reliance on off-label treatments and serve to fill an unmet treatment need. The objective of this article is to review evidence supporting the efficacy and safety of dapoxetine in the treatment of PE. MEDLINE, Web of Science, PICA, EMBASE and the proceedings of major international and regional scientific meetings were searched for publications or abstracts published during the period 1993–2012 that used the word ‘dapoxetine’ in the title, abstract or keywords. This search was then manually cross referenced for all papers. This review encompasses studies of dapoxetine pharmacokinetics, animal studies, human phase I, II and III studies, independent postmarketing and pharmacovigilance efficacy and safety studies and drug-interaction studies. Dapoxetine is a potent SSRI which is administered on demand 1–3 h prior to planned sexual contact. It is rapidly absorbed and eliminated, resulting in minimal accumulation, and has dose-proportional pharmacokinetics which are unaffected by multiple dosing. Dapoxetine 30 mg and 60 mg has been evaluated in five industry-sponsored randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in 6081 men aged at least 18 years. Outcome measures included stopwatch-measured intravaginal ejaculatory latency time (IELT), Premature Ejaculation Profile (PEP) inventory items, Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGIC) in PE, and adverse events. Mean IELT, all PEP items and CGIC improved significantly with both doses of dapoxetine versus placebo (all p <0.001). The most common treatment-related adverse effects included nausea (11.0% for 30 mg, 22.2% for 60 mg), dizziness (5.9% for 30 mg, 10.9% for 60 mg), and headache (5.6% for 30 mg, 8.8% for 60 mg), and evaluation of validated rated scales demonstrated no SSRI class-related effects with dapoxetine use. Dapoxetine, as the first drug developed for PE, is an effective and safe treatment for PE and represents a major advance in sexual medicine.

Keywords: dapoxetine, premature ejaculation, treatment, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors

Introduction

Over the past 20–30 years, the premature ejaculation (PE) treatment paradigm, previously limited to behavioural psychotherapy, has expanded to include drug treatment [Jannini et al. 2002; Masters and Johnson, 1970; Semans, 1956]. Animal and human sexual psychopharmacological studies have demonstrated that serotonin (5-hydroxy-tryptamine, 5-HT) and 5-HT receptors are involved in ejaculation and confirm a role for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the treatment of PE [Olivier et al. 1998; Pattij et al. 2005; Waldinger et al. 1998c]. Multiple well controlled evidence-based studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of SSRIs in delaying ejaculation, confirming their role as first-line agents for the treatment of lifelong and acquired PE [Waldinger et al. 2004]. More recently, there has been increased attention paid to the psychosocial consequences of PE, its epidemiology, its aetiology and its pathophysiology by clinicians and the pharmaceutical industry [Giuliano et al. 2008; Metz et al. 1997; Patrick et al. 2005; Porst et al. 2007; Symonds et al. 2003; Waldinger et al. 2005a].

Literature search methodology

All dapoxetine drug-treatment reports and studies were included in the review. In April 2012, MEDLINE, Web of Science, PICA, EMBASE and the proceedings of major international and regional scientific meetings were searched for publications or abstracts published during the period 1993–2012 and using the words dapoxetine, premature ejaculation, rapid ejaculation and ejaculation in the title, abstract or keywords. This search was then manually cross referenced for all papers. The full text of relevant articles was read and critiqued. Adequately powered randomized, controlled trials were considered the strongest form of evidence but all other articles were also considered.

Definition, prevalence and aetiology of premature ejaculation

Definition

There are multiple definitions of PE [American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Hatzimouratidis et al. 2010; Masters and Johnson, 1970; McMahon et al. 2004, 2008; Metz and McCarthy, 2003; Montague et al. 2004; World Health Organization, 1994]. The first contemporary multivariate evidence-based definition of lifelong PE was developed in 2008 by a panel of international experts, convened by the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM), who agreed that the diagnostic criteria necessary to define PE are time from penetration to ejaculation, inability to delay ejaculation and negative personal consequences from PE. This panel defined lifelong PE as a male sexual dysfunction characterized by ‘ejaculation which always or nearly always occurs prior to or within about one minute of vaginal penetration, the inability to delay ejaculation on all or nearly all vaginal penetrations, and the presence of negative personal consequences, such as distress, bother, frustration and/or the avoidance of sexual intimacy’ [McMahon et al. 2008].

This definition is supported by evidence from several controlled clinical trials which suggest that 80–90% of men with lifelong PE ejaculate within 60 s and the remaining 10–20% within 2 min (Figure 1) [McMahon, 2002; Waldinger et al. 1998a]. This definition should form the basis for the official diagnosis of lifelong PE. It is limited to heterosexual men engaging in vaginal intercourse as there are few studies available on PE research in homosexual men or during other forms of sexual expression. Preliminary recommendations of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual V (DSM-V) Committee suggest a DSM-V definition which parallels the definition recently adopted by the International Society for Sexual Medicine [Segraves, 2010].

Figure 1.

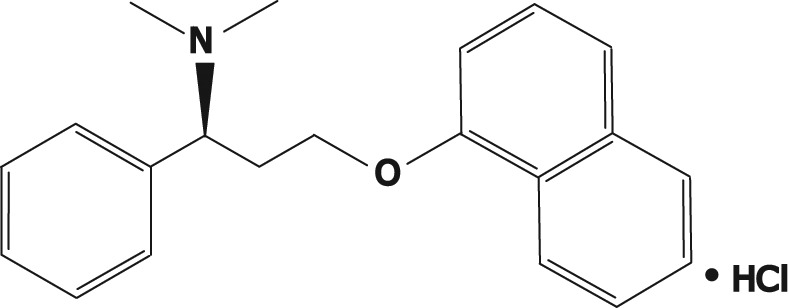

Molecular structure of dapoxetine: (+)-(S)-N,N-dimethyl-(α)-[2(1naphthalenyloxy)ethyl]-benzenemethanamine hydrochloride.

The ISSM panel concluded that there is insufficient published evidence to propose an evidence-based definition of acquired PE [McMahon et al. 2008]. However, recent data suggest that men with acquired PE have similar intravaginal ejaculation latency times (IELTs) and report similar levels of ejaculatory control and distress, also suggesting the possibility of a single unifying definition of PE [Porst et al. 2010].

The development of consensus statements by the International Consultation on Sexual Dysfunction and treatment guidelines by the ISSM has done much to standardize the management of PE [Althof et al. 2010; McMahon et al. 2004; Rowland et al. 2010].

Prevalence

Reliable information on the prevalence of lifelong and acquired PE in the general male population is lacking. Based on patient self reporting, PE is routinely characterized as the most common male sexual complaint and has been estimated to occur in 4–39% of men in the general community. Data from The Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors (GSSAB), an international survey investigating the attitudes, behaviours, beliefs, and sexual satisfaction of 27,500 men and women aged 40–80 years, reported the global prevalence of PE (based on subject self-reporting) to be approximately 30% across all age groups [Laumann et al. 2005; Nicolosi et al. 2004]. Perception of ‘normal’ ejaculatory latency varied by country and differed when assessed either by the patient or their partner [Montorsi, 2005]. A core limitation of the GSSAB survey stems from the fact that the youngest participants were aged 40 years, an age when the incidence of PE might be different from younger men [Jannini and Lenzi, 2005]. Contrary to the GSSAB study, the Premature Ejaculation Prevalence and Attitude Survey found the prevalence of PE among men aged 18–70 to be 22.7% [Porst et al. 2007].

However, there is a substantial disparity between the incidence of PE in epidemiological studies which rely upon patient self-reporting of PE or inconsistent and poorly validated definitions of PE [Giuliano et al. 2008; Jannini and Lenzi, 2005; Laumann et al. 1999; Patrick et al. 2005], and that suggested by community-based stopwatch studies of the IELT, the time interval between penetration and ejaculation which forms the basis of the ISSM definition of lifelong PE [McMahon et al. 2008; Waldinger et al. 2005a]. Normative community-based stopwatch studies demonstrate that the distribution of the IELT is positively skewed, with a median IELT of 5.4 min (range 0.55–44.1 min), decreases with age and varies between countries, and supports the notion that IELTs of less than 1 min are statistically abnormal compared with men in the general western population [Waldinger et al. 2005a]. Local and regional variations should be considered in the context of different cultural, religious and political influences.

Classification

In 1943, Schapiro proposed a distinction of PE into types A and B [Schapiro, 1943]. Men with type B PE have always suffered from a very rapid ejaculation (or short latency), whereas in type A PE, the rapid ejaculation develops later in life and is often associated with erectile dysfunction (ED). In 1989, these types were respectively referred to as lifelong (primary) and acquired (secondary) PE [Godpodinoff, 1989]. Over the years, other attempts have been made to identify various classifications of PE, including several that have been incorporated into PE definitions (e.g. global versus situational). In 2006, Waldinger proposed the existence of four PE subtypes, with different pathogenesis [Waldinger, 2006; Waldinger and Schweitzer, 2006]. Support for this new classification is gradually developing [Serefoglu et al. 2009, 2011].

Aetiology

Historically, attempts to explain the aetiology of PE have included a diverse range of biological and psychological theories. Most of these proposed aetiologies are not evidence based and are speculative at best. The determinants of PE are undoubtedly complex and multivariate, with the aetiology of lifelong PE different from that of acquired PE. Our understanding of the neurochemical central control of ejaculation is at best rudimentary although recent imaging and electrophysiological studies have identified increased and decreased neuronal activity in several brain areas during arousal and ejaculation [Hyun et al. 2008; McMahon et al. 2004].

Ejaculatory latency time is probably a genetically determined biological variable which differs between populations and cultures, ranging from extremely rapid through average to slow ejaculation. The view that some men have a genetic predisposition to lifelong PE is supported by animal studies showing a subgroup of persistent rapidly ejaculating Wistar rats [Pattij et al. 2005], an increased familial occurrence of lifelong PE [Waldinger et al. 1998c], a moderate genetic influence on PE in the Finnish twin study [Jern et al. 2007], and the recent report that genetic polymorphism of the 5-HT transporter gene determines the regulation of IELT [Janssen et al. 2009]. Acquired PE is commonly due to sexual performance anxiety [Hartmann et al. 2005], psychological or relationship problems [Hartmann et al. 2005], ED [Laumann et al. 2005; Jannini and Lenzi, 2005], and occasionally prostatitis [Screponi et al. 2001], hyperthyroidism [Carani et al. 2005], or during withdrawal/detoxification from prescribed [Adson and Kotlyar, 2003] or recreational drugs [Peugh and Belenko, 2001]. The acquired form of PE may be cured by medical or psychological treatment of the underlying cause [Waldinger and Schweitzer, 2008].

Pharmacological treatment of premature ejaculation

The off-label use of antidepressant SSRIs, including paroxetine, sertraline, fluoxetine, citalopram and fluvoxamine, and the serotonergic tricyclic clomipramine has revolutionized the approach to and treatment of PE. These drugs block axonal reuptake of serotonin from the synapse by 5-HT transporters, resulting in enhanced 5-HT neurotransmission, stimulation of postsynaptic membrane 5-HT2C receptors and ejaculatory delay. However, the lack of an approved drug and the total reliance on off-label treatment represents a substantial unmet treatment need. Consistent with this, one study suggests a low level of acceptance of off-label daily SSRIs and reports that 30% of men with PE seeking lifelong treatment declined this therapy, most often due to fear of using an ‘antidepressant drug’ and roughly 30% of patients who started therapy eventually discontinued it [Salonia et al. 2009]. Following cessation of an SSRI, IELT will return to the pretreatment value within 1–3 weeks in men with lifelong PE. However, there is some preliminary evidence to suggest that treatment of comorbid risk factors in men with acquired PE, for example, ED and performance anxiety, may be associated with sustained improvement in IELT following SSRI withdrawal [McMahon, 2002].

Dapoxetine

Dapoxetine {(+)-(S)-N,N-dimethyl-(α)-[2(1naphthal enyloxy)ethyl]-benzenemethanamine hydrochloride, Janssen Cilag (Johnson and Johnson, New Jersey USA)} is the first compound specifically developed for the treatment of PE. Dapoxetine is a potent SSRI (pKi = 8 nM), structurally similar to fluoxetine (Figure 1) [Sorbera et al. 2004]. Equilibrium radioligand binding studies using human cells demonstrate that dapoxetine binds to 5-HT, norepinephrine (NE) and dopamine (DA) reuptake transporters and inhibits uptake in the following order of potency: NE<5-HT>>DA [Gengo et al. 2005]. Brain positron emission tomography studies have demonstrated significant displaceable binding of radiolabelled dapoxetine in the cerebral cortex and subcortical grey matter [Livni et al. 1994]. The recent report that dapoxetine potently blocks cloned Kv4.3 potassium voltage-gated channels, which are involved in the regulation of neurotransmitter release, gives additional insight into the mechanism underlying some of the therapeutic actions of this drug [Jeong et al. 2012].

Pharmacokinetics and metabolism

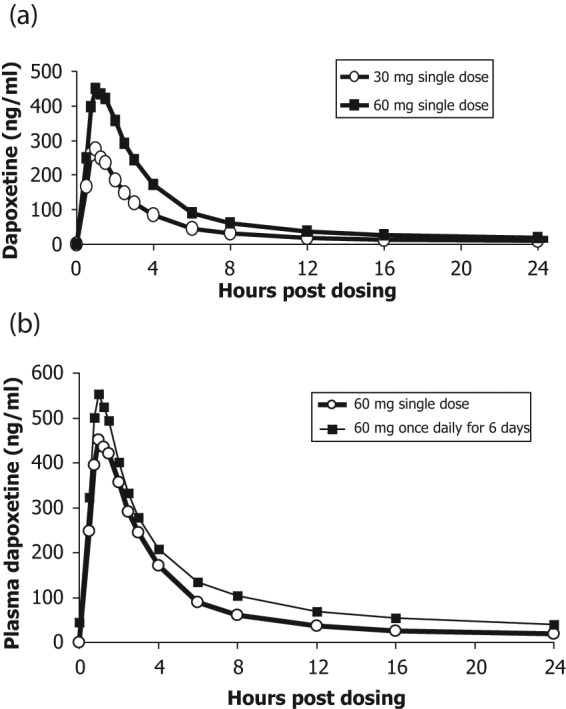

Dapoxetine undergoes rapid absorption and elimination resulting in minimal accumulation and has dose-proportional pharmacokinetics, which are unaffected by multiple dosing and do not vary between ethnic groups (Figure 2) [Dresser et al. 2006b; Dresser et al. 2004; Modi et al. 2006]. The pharmacokinetic profile of dapoxetine suggests that it is a good candidate for on-demand treatment of PE.

Figure 2.

Plasma concentration profiles of dapoxetine after administration of a single dose or multiple doses of dapoxetine 30 mg (a) and dapoxetine 60 mg (b) [Modi et al. 2006].

The pharmacokinetics of single doses and multiple doses over 6–9 days (30, 60, 100, 140 or 160 mg) of dapoxetine have been evaluated. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, single doses and multiple doses over 6 days of dapoxetine (60, 100, 140, or 160 mg) were administered to 77 healthy male volunteers [Dresser et al. 2004, 2006b; Thyssen et al. 2010]. Dapoxetine has a T max of 1.4–2.0 h and rapidly achieves peak plasma concentration (Cmax) following oral administration. Both plasma concentration and area under the curve (AUC) are dose dependent up to 100 mg. The mean half life of dapoxetine after a single dose was estimated using modelling as 1.3–1.5 h. Dapoxetine plasma concentrations rapidly decline to about 5% of Cmax at 24 h. The terminal half life of dapoxetine was 15–19 h after a single dose and 20–24 h after multiple doses of 30 and 60 mg respectively.

In a second pharmacokinetic study, single doses and multiple doses of dapoxetine (30 mg, 60 mg) were evaluated in a randomized, open-label, two-treatment, two-period, crossover study of 42 healthy male volunteers over 9 days [Modi et al. 2006]. Subjects received a single dose of dapoxetine 30 mg or 60 mg on day 1 (single-dose phase) and on days 4–9 (multiple-dose phase). Dapoxetine was rapidly absorbed, with mean maximal plasma concentrations of 297 and 498 ng/ml at 1.01 and 1.27 h after single doses of dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg, respectively (Table 1). Elimination of dapoxetine was rapid and biphasic, with an initial half life of 1.31 and 1.42 h, and a terminal half life of 18.7 and 21.9 h following single doses of dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg, respectively. The pharmacokinetics of dapoxetine and its metabolites were not affected by repeated daily dosing and steady state plasma concentrations were reached within 4 days, with only modest accumulation of dapoxetine (approximately 1.5 fold) (Figure 2(b)).

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetics of single doses of dapoxetine (30 mg, 60 mg) and effect of food on pharmacokinetics [Dresser et al. 2004, 2006b; Modi et al. 2006].

| Dapoxetine 30 mg | Dapoxetine 60 mg | |

|---|---|---|

| Cmax (ng/ml) | 297 | 349 |

| Tmax (h) | 1.01 | 1.27 |

| Initial half life (h) | 1.31 | 1.42 |

| Terminal half life (h) | 18.7 | 21.9 |

| Effect of high-fat meal | ||

| Cmax (fasted) | – | 443 |

| Cmax (high-fat meal) | – | 398 |

| Tmax (h) (fasted) | – | 1.30 |

| Tmax (h) (high-fat meal) | – | 1.83 |

Food does not have a clinically significant effect on dapoxetine pharmacokinetics. Mean maximal plasma concentrations of dapoxetine decrease slightly after a high-fat meal, from 443 ng/ml (fasted) to 398 ng/ml (fed), and are delayed by approximately 0.5 h following a high-fat meal (1.30 h fasted, 1.83 h fed) [Dresser et al. 2006b]. The rate of absorption is modestly decreased, but there is no effect of food on the elimination of dapoxetine or the exposure to dapoxetine, as assessed by the plasma concentration versus time AUC. The frequency of nausea is decreased after a high-fat meal [24% (7/29) of fasted subjects and 14% (4/29) of fed subjects respectively].

Dapoxetine is extensively metabolized in the liver by multiple isozymes to multiple metabolites, including desmethyldapoxetine, didesmethyldapoxetine and dapoxetine-n-oxide, which are eliminated primarily in the urine [Dresser et al. 2004; Modi et al. 2006]. Although didesmethyldapoxetine is equipotent to the parent dapoxetine, its substantially lower plasma concentration, compared with dapoxetine, limits its pharmacological activity and it exerts little clinical effect, except when dapoxetine is coadministered with cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) or CYP2D6 inhibitors.

Animal studies

Animal studies using rat experimental models have demonstrated that acute treatment with oral, subcutaneous and intravenous dapoxetine inhibits ejaculation at doses as low as 1 mg/kg. Dapoxetine appears to inhibit the ejaculatory reflex at a supraspinal level with the lateral paragigantocellular nucleus as a necessary brain structure for this effect [Clement et al. 2007].

Clement and colleagues reported the effects of intravenous dapoxetine on the emission and ejection phases of ejaculation using p-chloroamphetamine (PCA)-induced ejaculation as an experimental model of ejaculation in anesthetized rats [Clement et al. 2006]. Intraseminal vesicle pressure and electromyograms of bulbospongiosus muscles were used as physiological markers of the emission and ejection phases respectively. At all doses, dapoxetine significantly reduced the proportion of rats displaying PCA-induced ejaculation in a dose-dependent manner, from 78% of rats with vehicle to 33%, 22% and 13% of rats following intravenous dapoxetine 1, 3 and 10 mg/kg, respectively. Dapoxetine significantly decreased the AUC of PCA-induced intraseminal vesicle pressure increases and bulbospongiosus muscle contractile bursts by 78% at all doses, by 91% following dapoxetine 1 and 10 mg/kg, and by 85% following dapoxetine 3 mg/kg.

Using a different animal experimental model of the ejaculatory reflex in rats, Giuliano and colleagues measured the latency, amplitude and duration of pudendal motoneuron reflex discharges (PMRDs) elicited by stimulation of the dorsal nerve of the penis before and after intravenous injection of vehicle, dapoxetine or paroxetine (1, 3 and 10 mg/kg) [Giuliano et al. 2007]. At the three doses of dapoxetine tested, the latency of PMRD following stimulation of the dorsal nerve of the penis was significantly increased and the amplitude and duration of PMRD decreased from baseline values. Acute intravenous paroxetine appeared less effective than dapoxetine.

In a behavioural study of sexually experienced rats, Gengo and colleagues reported that treatment with subcutaneous or oral dapoxetine significantly delayed ejaculation compared with saline control (16 ± 4 min with subcutaneous administration versus 10 ± 1 min in saline controls, p < 0.05) when administered 15 min, but not 60 or 180 min prior to exposure to receptive females [Gengo et al. 2006]. The greatest delay in ejaculatory latency was observed in animals with shorter baseline latencies and oral dapoxetine did not affect the latency in rats with a baseline latency longer than 10 min.

Clinical efficacy

The results of two phase II and five phase III trials have been published [Buvat et al. 2009; Hellstrom et al. 2004, 2005; Kaufman et al. 2009; McMahon et al. 2010; Pryor et al. 2006]. All were conducted prior to the development of the ISSM definition of lifelong PE and instead used DSM-IV criteria and a baseline IELT of less than 2 min on 75% of at least four sexual intercourse events as inclusion criteria.

Phase II trials

Dapoxetine dose-finding data have been derived from two multicentre phase II studies and used to determine the appropriate doses for phase III studies. Both studies used a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, three-period, crossover study design and subjects with PE diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria and a baseline IELT of less than 2 min on 75% of at least four sexual intercourse events. The study drug was administered 1–2 h prior to planned sexual intercourse and subjects were required to attempt intercourse at least twice a week. The primary outcome measure was the partner-operated stopwatch IELT.

In study 1, 128/157 randomized subjects completed the study [Hellstrom et al. 2005]. Subjects were randomized to receive dapoxetine 20 mg, dapoxetine 40 mg or placebo for 4 weeks with no washout period between treatment arms. Baseline IELT (mean baseline IELT = 1.34 min) was estimated by patient recall. In study 2, 130/166 randomized subjects completed the study [Hellstrom et al. 2004]. Subjects were randomized to receive dapoxetine 60 mg, dapoxetine 100 mg or placebo for 2 weeks, separated by a 3-day washout period. Baseline IELT (mean baseline IELT = 1.01 min) was measured by partner-operated stopwatch.

The intention-to-treat analysis of both studies demonstrated that all four doses of dapoxetine were effective, superior to placebo and increased IELT 2.0–3.2 fold over baseline in a dose-dependent fashion (Table 2) [Hellstrom et al. 2004, 2005]. The magnitude of effect of dapoxetine 20 mg on IELT was small. The most commonly reported adverse events (AEs) were nausea, diarrhoea, headache, dizziness. The incidence of most AEs appeared to be dose dependent. The most common AE was nausea and occurred in 0.7%, 5.6% and 16.1% of subjects with placebo, dapoxetine 60 mg and dapoxetine 100 mg respectively. Overall, dapoxetine 60 mg was better tolerated than dapoxetine 100 mg. Based on these results, doses of 30 mg and 60 mg were chosen for further investigation in phase III efficacy and safety studies.

Table 2.

Results of dapoxetine phase II and III studies [Buvat et al. 2009; Hellstrom et al. 2004, 2005; Kaufman et al. 2009; McMahon et al. 2010; Pryor et al. 2006].

| Phase II studies |

Phase III studies (pooled) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 [Hellstrom et al. 2005] | Study 2 [Hellstrom et al. 2004] | Studies 1–5 [Buvat et al. 2009; Kaufman et al. 2009; McMahon et al. 2010; Pryor et al. 2006] | |||||||

| Age range (years) | 18–60 | 18–65 | 18–82 | ||||||

| Inclusion criteria, IELT | DSM-IV TR, <2 min estimated | DSM-IV TR, <2 min by stopwatch | DSM-IV TR, <2 min by stopwatch | ||||||

| Number of subjects | 157 | 166 | 6081 | ||||||

| Treatment period | 4 weeks per treatment | 2 weeks per treatment | 9-24 weeks, parallel, fixed dose | ||||||

| Washout period | None | 72 hours | None | ||||||

| Dapoxetine dose (mg) | 20 (n = 145) | 40 (n = 141) | Placebo (n = 142) | 60 (n = 144) | 100 (n = 155) | Placebo (n = 145) | 30 (n = 1613) | 60 mg (n = 1611) | Placebo (n = 1608) |

| Mean baseline IELT | 1.34 | 1.34 | 1.34 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Mean treatment IELT | 2.72* | 3.31† | 2.22 | 2.86† | 3.24† | 2.07 | 3.1† | 3.6† | 1.9 |

| IELT fold increase | 2.0 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 1.6 |

| ‘Good/very good’ control | |||||||||

| Baseline (%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Study end (%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 11.2† | 26.2† | 30.2 |

| ‘Good/very good’ satisfaction | |||||||||

| Baseline (%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 15.5 | 14.7 | 15.5 |

| Study end (%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 24.4† | 37.9† | 42.8 |

| ‘Quite a bit/extreme’ personal distress | |||||||||

| Baseline (%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 73.5 | 71.3 | 69.7 |

| Study end (%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 41.9† | 28.2† | 22.2 |

| ‘Quite a bit/extreme’ interpersonal distress | |||||||||

| Baseline (%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 38.5 | 38.8 | 36.1 |

| Study end (%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 23.8† | 6.0† | 12.3 |

| Discontinuation due to adverse event | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 3.5 | 8.8 | 1.0 |

p = 0.042, †p < 0.0001 versus placebo.

DSM-IV TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition revised; IELT, intravaginal ejaculation latency time.

Phase III trials

The five randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III clinical trials comprised two identically designed studies conducted in the USA [Pryor et al. 2006], an international study conducted in 16 countries in Europe, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Israel, Mexico and South Africa [Buvat et al. 2009], a North American safety study [Kaufman et al. 2009] and an Australian and Asia-Pacific country study [McMahon et al. 2010]. The treatment period ranged from 9 to 24 weeks. Overall, 6081 men with a mean age of 40.6 years (range 18–82 years) from 32 countries were enrolled with 4232 (69.6%) subjects completing their study (Table 2). This is the largest efficacy and safety database for any agent intended to treat PE.

The DSM-IV-TR criteria and a baseline IELT of less than 2 min on 75% of at least four sexual intercourse events were used to enrol subjects in four of the five phase III studies [Buvat et al. 2009; McMahon et al. 2010; Pryor et al. 2006]. Baseline average IELT was 0.9 min for subjects overall. However, 58% of subjects also met the ISSM criteria for lifelong PE [Porst et al. 2010]. Subjects reported having had PE for an average of 15.1 years, with 64.9% of subjects classified by the investigator as having lifelong PE at screening. Demographic and baseline characteristics were similar across studies, allowing analysis of pooled phase III data.

Outcome measures included stopwatch IELT, the Premature Ejaculation Profile (PEP), a validated self-administered four-item tool that includes measures of perceived control over ejaculation, satisfaction with sexual intercourse, ejaculation-related personal distress, ejaculation-related interpersonal difficulty [Patrick et al. 2009], and subject response to a multidimensional Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGIC) in PE question: ‘Compared to the start of the study, would you describe your premature ejaculation problem as much worse, worse, slightly worse, no change, slightly better, better, or much better?’

An analysis of pooled phase III data confirms that dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg increased IELT and improved patient-reported outcomes (PROs) of control, ejaculation-related distress, interpersonal distress and sexual satisfaction compared with placebo. Efficacy results were similar among each of the individual trials and for a pooled analysis, indicating that dapoxetine is consistently more efficacious than placebo regardless of a subject’s demographic characteristics.

Increases in mean average IELT (Table 2) were significantly greater with both doses of dapoxetine versus placebo beginning with the first dose of study medication (dapoxetine 30 mg, 2.3 min; dapoxetine 60 mg, 2.7 min; placebo, 1.5 min; p < 0.001 for both) and at all subsequent time points (all p < 0.001). By week 12, mean average IELT had increased to 3.1 and 3.6 min with dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg respectively (versus 1.9 min with placebo; p < 0.001 for both; Table 2).

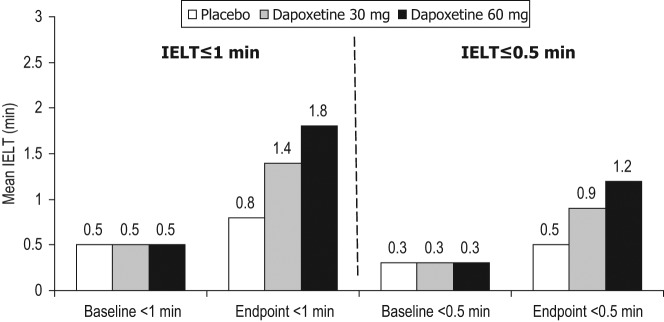

However, as IELT in subjects with PE is distributed in a positively skewed pattern, reporting IELTs as arithmetic means may overestimate the treatment response and the geometric mean IELT is more representative of the actual treatment effect [Waldinger et al. 2008]. Geometric mean average IELT increased from approximately 0.8 min at baseline to 2.0 and 2.3 min with dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg respectively (versus 1.3 min with placebo; p < 0.001 for both). Furthermore, as subjects have a broad range of baseline IELT values (0–120 s), reporting mean raw trial-end IELT may be misleading by incorrectly suggesting all subjects respond to that extent. The trial-end fold increase in geometric mean IELT compared with baseline is more representative of true treatment outcome and must be regarded as the contemporary universal standard for reporting IELT. Geometric mean IELT fold increases of 2.5 and 3.0 were observed with dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg respectively versus 1.6 for placebo (p < 0.0001 for both, Table 2). Fold increases were greater among men with very short baseline IELT values, suggesting that dapoxetine may be a useful treatment option for men with severe forms of PE, including anteportal ejaculation. Subjects with baseline average IELTs of 0.5–1.0 min and up to 0.5 min showed fold increases of 2.4 and 3.4, respectively with dapoxetine 30 mg, and 3.0 and 4.3 with dapoxetine 60 mg compared with 1.6 and 1.7, respectively, with placebo.

Dapoxetine phase III study design was limited by the use of DSM-IV-TR criteria and a baseline IELT of less than 2 min on 75% of at least four sexual intercourse attempts and enrolment of men with lifelong and acquired PE. The evidence-based ISSM definition of lifelong PE had not been developed when the phase III clinical trial programme was developed [McMahon et al. 2008]. Despite these limitations, the overall population appears reasonably representative of the ISSM definition of lifelong PE (64.9% had lifelong PE; 58% had an IELT of less than 1 min). In a post hoc analysis of five large randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III dapoxetine trials in the context of the new ISSM criteria, similar results were observed in men with IELTs up to 1 min and up to 0.5 min at baseline [McMahon and Porst, 2011]. Progressively greater fold increases were observed with decreasing baseline average IELTs. Subjects with baseline average IELTs of 1.5–2 min, 1–1.5 min, 0.5–1 min and less than 0.5 min showed geometric mean fold increases of 1.5, 1.6, 1.6 and 1.7, respectively, with placebo treatment; 2.2, 2.3, 2.4 and 3.4, respectively, with dapoxetine 30 mg; and 2.6, 2.5, 3.0 and 4.3 with dapoxetine 60 mg. This post hoc analysis is limited by retrospective application of the ISSM definition of lifelong PE to previously conducted intervention studies which employed differing inclusion/exclusion criteria and study endpoints. However, the attempt to approximate data from studies enrolling a heterogeneous population of lifelong and acquired PE to the ISSM definition of lifelong PE is somewhat balanced by the recently published post hoc analysis of dapoxetine phase III baseline and treatment outcome data suggesting that there are substantial similarities in baseline IELT, PROs and response to dapoxetine between both PE sub populations [Porst et al. 2010].

Overall, subjects reported significant improvements in all PEP items with dapoxetine (p ≤ 0.001 versus placebo for all) and the results were similar for men with IELT values of less than 1 min at baseline [McMahon et al. 2011]. ‘Good’ or ‘very good’ control over ejaculation was reported by less than 1% across groups at baseline and increased among the overall population (26.2% with dapoxetine 30 mg and 30.2% with dapoxetine 60 mg versus 11.2% with placebo; p < 0.001 for both) and among men with IELT values of less than 1 min at baseline (19.7% with dapoxetine 30 mg and 26.0% with dapoxetine 60 mg versus 7.2% with placebo; p < 0.001 for both) at 12 weeks (p < 0.001 for both; Table 2) [McMahon and Porst, 2011]. Similarly, ‘good’ or ‘very good’ satisfaction with sexual intercourse was reported by approximately 15.0% of men across groups at baseline and increased among the overall population (37.9% with dapoxetine 30 mg and 42.8% with dapoxetine 60 mg versus 24.4% with placebo; p < 0.001 for both) and among men with IELT values of less than 1 min at baseline (32.9% with dapoxetine 30 mg and 40.0% with dapoxetine 60 mg versus 32.9% with placebo; p < 0.001 for both) at 12 weeks (p < 0.001 for both; Table 2).

While approximately 70% of subjects across groups reported ‘quite a bit’ or ‘extremely’ for their level of ejaculation-related personal distress at baseline, by week 12 this decreased to 28.2% and 22.2% with dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg, respectively, versus 41.9% with placebo (p < 0.001 for both; Table 2), and to 34.9% and 28.8% with dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg, respectively, among men with IELT values of less than 1 min at baseline who fulfil new ISSM criteria (versus 50.7% with placebo, p < 0.001) [McMahon and Porst, 2011].

Approximately one-third of subjects reported ‘quite a bit’ or ‘extremely’ for their level of ejaculation-related interpersonal difficulty at baseline. By week 12, this decreased among the overall population to 16.0% and 12.3% with dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg, respectively (versus 23.8% with placebo, p < 0.001) and to 17.7% and 13.9% with dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg, respectively, among men with IELT values of less than 1 min at baseline (versus 28.2% with placebo, p < 0.001) (p < 0.001 for both; Table 2). Significantly more men receiving dapoxetine 30 or 60 mg reported that their PE was at least ‘better’ at week 12 (30.7% and 38.3%, respectively, among the overall population and 25.2% and 34.9% for men with IELT values <1 min at baseline respectively) compared with placebo (13.9% and 9.4% among the overall population and for men with IELT values <1 min at baseline, respectively; p ≤ 0.05 for all) [McMahon and Porst, 2011].

A significantly greater percentage of subjects reported that their PE was ‘better’ or ‘much better’ at week 12 with dapoxetine 30 (30.7%) and 60 mg (38.3%) than with placebo (13.9%; p < 0.001 for both). Similarly, 62.1% and 71.7% of subjects reported that their PE was at least ‘slightly better’ at week 12 with dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg, respectively, compared with 36.0% with placebo (p < 0.001 for both).

Several studies have reported that the effects of PE on the partner are integral to understanding the impact of PE on the man and on the sexual relationship [Byers and Grenier, 2003; McMahon, 2008; Metz and Pryor, 2000; Symonds et al. 2003]. If PE is to be regarded as a disorder that affects both subjects and their partners, partner PROs must be regarded as important measures in determining PE severity and treatment outcomes. Female partners reported their perception of the man’s control over ejaculation and CGIC, their own satisfaction with sexual intercourse, interpersonal difficulty and personal distress. A significantly greater percentage of female partners reported that the man’s control over ejaculation was ‘good’ or ‘very good’ with dapoxetine 30 mg (26.7%) and 60 mg (34.3%) versus placebo at week 12 (11.9%; p < 0.0001 for both). Similarly, a significantly greater percentage of female partners reported that the man’s PE was at least ‘better’ with dapoxetine 30 mg (27.5%) and 60 mg (35.7%) versus placebo (9.0%; p < 0.001 for both). A greater percentage of female partners reported that their own satisfaction with sexual intercourse was ‘good’ or ‘very good’ with dapoxetine 30 mg (37.5%) and 60 mg (44.7%) versus placebo (24.0%; p < 0.001 for both). Finally, there were significant decreases in both ejaculation-related personal distress and interpersonal difficulty in female partners of men treated with dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg versus placebo (p < 0.001 for both) [Buvat et al. 2009].

Postmarketing/pharmacovigilance trials

Despite regulatory approval in multiple markets, only one independent postmarketing study has been published [Pastore et al. 2012]. In an open-label flexible dose trial of dapoxetine in 19 men with lifelong PE and an arithmetic mean baseline IELT, of less than 1 min, 12 weeks of treatment with dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg was associated with a 5.4- and 5.9-fold increase in arithmetic mean IELT, respectively [Pastore et al. 2012]. First-dose nausea, which progressively attenuated and disappeared by study end, was experienced by 12.5% and 28.5% of subjects on dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg respectively.

Safety and tolerability

Across trials, dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg were well tolerated with a low incidence of severe AEs. More than 50% of all phase III AEs were reported at the first follow-up visit after 4 weeks of treatment and typically included gastrointestinal and central nervous system symptoms. The most frequently reported AEs were nausea, diarrhoea, headache, dizziness, insomnia, somnolence, fatigue and nasopharyngitis (Table 3). Unlike other SSRIs used to treat depression, which has been associated with high incidences of sexual dysfunction [Lane, 1997; Montejo et al. 2001], dapoxetine was associated with low rates of sexual dysfunction. The most common AE in this category was ED (placebo, 1.6%; dapoxetine 30 mg as needed, 2.3%; dapoxetine 60 mg as needed, 2.6%; dapoxetine 60 mg daily, 1.2%). AEs were dose dependent and generally coincided with the pharmacokinetic profile of dapoxetine, occurring at the approximate time of peak serum concentrations (~1.3 h) and lasting for approximately 1.5 h. Most AEs were mild to moderate in severity, and few subjects across groups reported severe (~3%) or serious (≤1%) AEs. AEs led to the discontinuation of placebo, dapoxetine 30 mg as needed, dapoxetine 60 mg as needed and dapoxetine 60 mg daily in 1.0%, 3.5%, 8.8% and 10.0% of subjects, respectively.

Table 3.

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in at least 2% of subjects in pooled phase III data [Buvat et al. 2009; Kaufman et al. 2009; McMahon et al. 2010; Pryor et al. 2006].

| Adverse event n (%) | Placebo (n = 1857) | Dapoxetine 30 mg as needed (n = 1616) | Dapoxetine 60 mg as needed (n = 2106) | Dapoxetine 60 mg daily (n = 502) | Total dapoxetine (n = 4224) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea | 41 (2.2) | 178 (11.0) | 467 (22.2) | 86 (17.1) | 731 (17.3) |

| Dizziness | 40 (2.2) | 94 (5.8) | 230 (10.9) | 75 (14.9) | 399 (9.4) |

| Headache | 89 (4.8) | 91 (5.6) | 185 (8.8) | 56 (11.2) | 332 (7.9) |

| Diarrhoea | 32 (1.7) | 56 (3.5) | 145 (6.9) | 47 (9.4) | 248 (5.9) |

| Somnolence | 10 (0.5) | 50 (3.1) | 98 (4.7) | 18 (3.6) | 166 (3.9) |

| Fatigue | 23 (1.2) | 32 (2.0) | 86 (4.1) | 46 (9.2) | 164 (3.9) |

| Insomnia | 28 (1.5) | 34 (2.1) | 83 (3.9) | 44 (8.8) | 161 (3.8) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 43 (2.3) | 51 (3.2) | 61 (2.9) | 17 (3.4) | 129 (3.1) |

Cardiovascular safety

The cardiovascular assessment of dapoxetine was conducted throughout all stages of drug development, with findings from preclinical safety pharmacology studies, phase I clinical pharmacology studies investigating the effect of dapoxetine on QT/corrected QT (QTc) intervals in healthy men, and phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled studies evaluating the safety (and efficacy) of the drug [Kowey et al. 2011]. Preclinical safety pharmacology studies did not suggest an adverse electrophysiologic or hemodynamic effect with concentrations of dapoxetine up to twofold greater than recommended doses. Phase I clinical pharmacology studies demonstrated that dapoxetine did not prolong the QT/QTc interval and had neither clinically significant electrocardiographic effects nor evidence of delayed repolarization or conduction effects, with dosing up to fourfold greater than the maximum recommended dosage [Modi et al. 2009]. Phase III clinical studies of dapoxetine in men with PE indicated that dapoxetine was generally safe and well tolerated with the dosing regimens used (30 mg and 60 mg as required) [Buvat et al. 2009; Kaufman et al. 2009; McMahon et al. 2010, 2011; Pryor et al. 2006; Shabsigh et al. 2008].

Special attention was given to cardiovascular-related safety issues since syncope has been reported with marketed SSRIs and there were five cases of vasovagal syncope during dapoxetine phase I studies [Modi et al. 2009]. Events of syncope were reported during the clinical development programme, with the majority occurring during study visits (on site) on day 1 following administration of the first dose when various procedures (e.g. orthostatic manoeuvres, venipunctures) were performed, suggesting that the procedures contributed to the incidence of syncope. Across all five trials, syncope (including loss of consciousness) occurred in 0.05%, 0.06% and 0.23% of subjects on placebo, dapoxetine 30 mg and dapoxetine 60 mg, respectively. Syncope was not associated with symptomatic or sustained tachyarrhythmia during Holter electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring in 3353 subjects [Buvat et al. 2009; Kaufman et al. 2009; McMahon et al. 2010, 2011]. The incidence of Holter-detected nonsustained ventricular tachycardia was similar between dapoxetine-treated subjects and those who received placebo, suggesting that dapoxetine is not arrhythmogenic and that tachyarrhythmia is thus unlikely to be the underlying mechanism responsible for syncope seen in the dapoxetine clinical programme. There was a statistically nonsignificant increase in the number of single ventricular and supraventricular ectopic beats in the dapoxetine groups, but this finding is not considered clinically meaningful given the generally benign nature of ventricular ectopic beats occurring on their own in the absence of structural heart disease [Ng, 2006]. Syncope appeared to be vasovagal in nature and generally occurred within 3 h of dosing. Syncope was more common with the first dose of dapoxetine, occurring in 0.19% of subjects with the first dose of dapoxetine versus 0.08% with a subsequent dose. Syncope occurred more frequently when dapoxetine was administered on site (0.31%) versus off site (0.08%), which may relate to on-site study-related procedures such as venipuncture or orthostatic manoeuvres that are known to be associated with syncope. This was consistent with previous reports showing that these and similar factors contribute to or trigger vasovagal syncope. Findings of the dapoxetine development programme demonstrate that dapoxetine is associated with vasovagal-mediated (neurocardiogenic) syncope. No other associated significant cardiovascular AEs were identified.

Neurocognitive safety

Studies of SSRIs in patients with major psychiatric disorders, for example depression or obsessive compulsive disorder, suggest that SSRIs are potentially associated with certain safety risks, including neurocognitive AEs such as anxiety, hypomania, akathisia and changes in mood [Coupland et al. 1996; Khan et al. 2003; Tamam and Ozpoyraz, 2002; Zajecka et al. 1997]. Systematic analysis of randomized, controlled studies suggested a small increase in the risk of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts in youth [Khan et al. 2003] but not in adults [Khan et al. 2003; Mann et al. 2006]. However, these SSRI safety risks have not been previously evaluated in men with PE. In the North American safety study [Kaufman et al. 2009] and the International Study [Buvat et al. 2009], SSRI-related neurocognitive side effects such as changes in mood, anxiety, akathisia or suicidality or sexual dysfunction were evaluated using a range of validated outcome measures including the Beck Depression Inventory II, the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, the Hamilton Anxiety Scale, the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale and the International Index of Erectile Function. Dapoxetine had no effect on mood and was not associated with anxiety, akathisia or suicidality.

Withdrawal syndrome

Chronic SSRI treatment for psychiatric conditions is known to predispose patients to withdrawal symptoms if medication is suspended abruptly [Zajecka et al. 1991, 1997]. The SSRI withdrawal syndrome is characterized by dizziness, headache, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea and occasionally agitation, impaired concentration, vivid dreams, depersonalization, irritability and suicidal ideation [Black et al. 2000; Ditto, 2003]. The risk of dapoxetine withdrawal syndrome was assessed with the Discontinuation-Emergent Signs and Symptoms (DESS) checklist following a 1-week withdrawal period during which subjects were re-randomized to either continue treatment with on-demand dapoxetine, daily dapoxetine or placebo, or to switch from dapoxetine to placebo. The DESS comprises 43 possible withdrawal signs and symptoms, each rated and scored as new, old and worse, unchanged or improved or absent. There was a low incidence of SSRI withdrawal syndrome across treatment groups that was similar among patients who continued to take dapoxetine or placebo and those who switched to placebo during a 1-week withdrawal period. In the International Study, the incidence of discontinuation syndrome was 3.0%, 1.1% and 1.3% for those continuing to take dapoxetine 30 mg, 60 mg as needed and placebo respectively, and 3.3% for those who switched from dapoxetine 60 mg as needed to placebo [Buvat et al. 2009]. No subjects switching from dapoxetine 30 mg as needed to placebo in this study showed evidence of the discontinuation syndrome. Dapoxetine is the only SSRI for which these symptoms have been systematically evaluated in a PE population. The lack of chronic serotonergic stimulation with on-demand dapoxetine precludes serotonin receptor desensitization and the downregulation of postsynaptic serotonin receptors that typically occurs with chronic SSRI use, so that on-demand dosing for PE may minimize the risk of withdrawal symptoms [Waldinger, 2007].

Drug interactions

No drug–drug interactions associated with dapoxetine have been reported. Coadministration of dapoxetine with ethanol did not produce significant changes in dapoxetine pharmacokinetics [Modi et al. 2007]. Mean peak plasma concentrations of dapoxetine, its metabolites and ethanol did not significantly change with coadministration and there were no clinically significant changes in ECGs, clinical laboratory results, physical examination and no serious AEs. Dapoxetine pharmacokinetics were similar with administration of dapoxetine alone and coadministration of tadalafil or sildenafil; the three treatments demonstrated comparable plasma concentration profiles for dapoxetine [Dresser et al. 2006a]. Dapoxetine absorption was rapid, and was not affected by coadministration of tadalafil or sildenafil. Following the peak (i.e. C max), dapoxetine elimination was rapid and biphasic with all three treatments, with an initial half life of 1.5–1.6 h and a terminal half life of 14.8–17.1 h. Plasma dapoxetine concentrations were less than 5% of C max by 24 h. Dapoxetine AUCinf remained unchanged when tadalafil was administered concomitantly; concomitant administration of sildenafil increased the dapoxetine AUCinf by 22%. However, this was not regarded as clinically important as dapoxetine pharmacokinetics were similar. Dapoxetine had no clinically important effects on the pharmacokinetics or orthostatic profile of the adrenergic α-antagonist tamsulosin in men on a stable tamsulosin regimen [Modi et al. 2008].

Coadministered potent CYP2D6 (desipramine, fluoxetine) or CYP3A4 (ketoconazole) inhibitors may increase dapoxetine exposure by up to twofold. Coadministration of dapoxetine and potent CYP3A4 such as ketoconazole is contraindicated. Caution should be exercised in coadministration of dapoxetine and moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors and potent CYP2D6 inhibitors such as fluoxetine. Doses up to 240 mg, fourfold the recommended maximum dose, were administered to healthy volunteers in the phase I studies and no unexpected AEs were observed

Dosage and administration

The recommended starting dose for all patients is 30 mg, taken as needed approximately 1–3 h prior to sexual activity. The maximum recommended dosing frequency is once every 24 h. If the effect of 30 mg is insufficient and the side effects are acceptable, the dose may be increased to the maximum recommended dose of 60 mg.

Regulatory status

Dapoxetine was originally developed by Eli Lilly and Company as an antidepressant. The patent was sold to Johnson & Johnson in December 2003. In 2004, a New Drug Application (NDA) for dapoxetine was submitted to the FDA by the ALZA Corporation, a division of Johnson & Johnson, for the treatment of PE. The FDA issued a ‘not-approvable’ letter for dapoxetine in October 2005, requiring additional clinical efficacy and safety data. Following completion of three additional efficacy/safety studies, an expanded dossier of safety and efficacy data was submitted to health authorities and dapoxetine received approval in Sweden, Finland, Austria, Portugal, Germany, Italy, Spain, Mexico, South Korea and New Zealand in 2009/2010. Approval is anticipated in other European countries. Approval for dapoxetine has been granted by the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) but the drug has yet to be launched. In addition, filings for approval have been submitted in several other countries. Dapoxetine is not approved in the USA where phase III study continues.

The place of dapoxetine in the treatment of premature ejaculation

Men complaining of PE should be evaluated with a detailed medical and sexual history, a physical examination and appropriate investigations to establish the true presenting complaint, and identify obvious biological causes such as ED or genital/lower urinary tract infection [Althof et al. 2010; Jannini et al. 2011]. The multivariate evidence-based ISSM definition of lifelong PE provides the clinician with a discriminating diagnostic tool and should form the basis for the office diagnosis of lifelong PE [McMahon et al. 2008]. Recent data suggest that men with acquired PE have similar IELTs and report similar levels of ejaculatory control and distress, suggest the possibility of a single unifying definition of PE [Porst et al. 2010].

The dapoxetine phase II and III study enrolment criteria may result in a subject population who are not totally representative of men who actively seek treatment for PE. The use of the authority-based and not evidence-based DSM-IV-TR and baseline IELT of less than 2 min as dapoxetine phase II and III study inclusion criteria is likely to be associated with a high false-positive diagnosis of PE [Waldinger et al. 2005b]. This potential for errors in the diagnosis of PE was demonstrated in two recent observational studies in which PE was diagnosed solely by the application of the DSM-IV-TR definition [Giuliano et al. 2007; Patrick et al. 2005]. In one study, the IELT range extended from 0 to almost 28 min in DSM-IV-TR diagnosed PE, with 48% of subjects having an IELT in excess of 2 min. In addition, several studies suggest that 80–90% of men seeking treatment for lifelong PE ejaculate within 1 min [McMahon, 2002; Waldinger et al. 1998a; Waldinger et al. 2007]. These data form the basis for the operationalization of IELT in the ISSM definition of lifelong PE to ‘less than about one minute’ [McMahon et al. 2008]. However, in 58% of phase III subjects who met the ISSM criteria for lifelong PE, IELT fold increases were superior to and PRO/CGIC score equivalent to the entire study population, suggesting that the flawed inclusion criteria did not affect the study conclusions.

Effective pharmacological treatment of PE has previously been limited to daily off-label treatment with paroxetine 10–40 mg, clomipramine 12.5–50 mg, sertraline 50–200 mg, fluoxetine 20–40 mg and citalopram 20–40 mg (Table 4) [McMahon et al. 2004]. Following acute on-demand administration of a SSRI, increased synaptic 5-HT neurotransmission is downregulated by presynaptic autoreceptors to prevent overstimulation of postsynaptic 5-HT2C receptors. However, during chronic daily SSRI administration, a series of synaptic adaptive processes which may include presynaptic autoreceptor desensitization, greatly enhances synaptic 5-HT neurotransmission [Waldinger et al. 1998b]. As such, daily dosing of off-label antidepressant SSRIs is likely to be associated with more ejaculatory delay than on-demand dapoxetine, although well designed controlled head-to-head comparator studies have not been conducted. A meta-analysis of published efficacy data suggests that paroxetine exerts the strongest ejaculation delay, increasing IELT approximately 8.8-fold over baseline [Waldinger, 2003]. Whilst daily dosing of off-label antidepressant SSRIs is an effective treatment for men with anteportal or severe PE with very short IELTs, the higher fold increases of dapoxetine in this patient population suggest that dapoxetine is also a viable treatment option (Figure 3). There are currently no published data which identify a meaningful and clinically significant threshold response to treatment. The point at which the IELT fold increase achieved by intervention is associated with a significant reduction in personal distress probably represents a measure of intervention success. These data are currently not available but the author’s anecdotal impression, derived from treatment of patients, suggests that a three- to fourfold increase in IELT, as seen with dapoxetine, represents the threshold of intervention success. Similarly, there are no current data to suggest that fold increases above this threshold are associated with higher levels of patient satisfaction.

Table 4.

Comparison of fold increases in intravaginal ejaculation latency time (IELT) with meta-analysis data for daily paroxetine, sertraline, fluoxetine, clompipramine [Waldinger et al. 2004] and phase III data for on-demand dapoxetine [Buvat et al. 2009; Kaufman et al. 2009; McMahon et al. 2010; Pryor et al. 2006].

| Drug | Regulatory approval for PE | Dose | Mean fold increase in IELT |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSRI antidepressants | |||

| Paroxetine | Yes* | 10–40 mg/day | 8.8 |

| Sertraline | No | 25–200 mg/day | 4.1 |

| Fluoxetine | No | 5–20 mg/day | 3.9 |

| Serotonergic tricyclic antidepressant | |||

| Clomipramine | No | 25–50 mg/day | 4.6 |

| Dapoxetine | Yes† | 30–60 mg 1–3 h prior to intercourse | 2.5–3.0 |

| Placebo | − | − | 1.4 |

Mexico.

See text for full details of regulatory approval.

IELT, intravaginal ejaculation latency time; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Figure 3.

Intravaginal ejaculation latency times (IELTs) at endpoint for baseline IELT up to 1 min and up to 0.5 min for placebo, dapoxetine 30 mg (IELT fold increase: <0.5 min 3.4, <1 min 2.7) and dapoxetine 60 mg (IELT fold increase: <0.5 min 4.3, <1 min 3.4) [McMahon et al. 2010].

Dapoxetine can be used in men with either lifelong or acquired PE. Treatment should be initiated at a dose of 30 mg and titrated to a maximum dose of 60 mg based upon response and tolerability. In men with acquired PE and comorbid ED, dapoxetine can be coprescribed with a phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitor drug.

The criteria for the ideal PE drug remain controversial. However, the author is of the opinion that many men may prefer the convenience of ‘on-demand’ dosing of dapoxetine compared with daily dosing. Men who infrequently engage in sexual intercourse may prefer on-demand treatment, whilst men in established relationships may prefer the convenience of daily medication. Well designed preference trials will provide additional detailed insight into the role of on-demand dosing.

As any branch of medicine evolves, many drugs are routinely used ‘off label’ but may be regarded as part of standard care for a condition. Although off-label drug use is common, it is often not supported by strong evidence [Radley et al. 2006]. Although the methodology of the initial off-label daily SSRI treatment studies was poor, later double-blind and placebo-controlled studies of relatively small study populations (<100 subjects) confirmed their efficacy [Atmaca et al. 2002; Goodman, 1980; Kara et al. 1996; McMahon, 1998; Waldinger, 2003; Waldinger et al. 1994]. However, few studies included control over ejaculation and PE-related distress or bother as enrolment criteria or used validated patient-reported outcome instruments to evaluate these parameters. Furthermore, reporting of treatment-related AEs has been inconsistent across these trials. Currently, dapoxetine has the largest efficacy and safety database for use in men with PE, and it is the only agent for which SSRI class-related effects have been studied in a PE population. Unlike dapoxetine, most off-label SSRI drugs have not been specifically evaluated for known class-related safety effects, including potential for withdrawal effects, treatment-emergent suicidality, and effects on mood and affect in men with PE. These studies fail to provide the same robust level of efficacy and safety evidence found in the dapoxetine phase III study populations of over 6000 subjects. Although regulatory approval is not always synonymous with superior treatment outcomes, it does assure prescribers that expert and regulatory peer review has demonstrated drug efficacy and safety.

Conclusions

Dapoxetine is an effective, safe and well tolerated on-demand treatment for PE and, in the opinion of the author, is likely to fulfil the treatment needs of most patients. Although daily off-label antidepressant SSRIs are effective treatments for PE, supportive studies are limited by small study populations, infrequent use of PROs of control, distress and satisfaction as outcome measures and inconsistent reporting of known SSRI class-related safety effects. Currently, dapoxetine has the largest efficacy and safety database for use in men with PE, and it is the only agent for which SSRI class-related effects have been studied in a PE population.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: Dr Chris McMahon is an investigaror, consultant and speaker for Johnson and Johnson.

References

- Adson D., Kotlyar M. (2003) Premature ejaculation associated with citalopram withdrawal. Ann Pharmacother 37: 1804–1806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althof S., Abdo C., Dean J., Hackett G., McCabe M., McMahon C., et al. (2010) International Society for Sexual Medicine’s guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of premature ejaculation. J Sex Med 7: 2947–2969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed revised. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association [Google Scholar]

- Atmaca M., Kuloglu M., Tezcan E., Semercioz A. (2002) The efficacy of citalopram in the treatment of premature ejaculation: a placebo-controlled study. Int J Impot Res 14: 502–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black K., Shea C., Dursun S., Kutcher S. (2000) Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: proposed diagnostic criteria. J Psychiatry Neurosci 25: 255–261 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buvat J., Tesfaye F., Rothman M., Rivas D., Giuliano F. (2009) Dapoxetine for the treatment of premature ejaculation: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial in 22 countries. Eur Urol 55: 957–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers E., Grenier G. (2003) Premature or rapid ejaculation: heterosexual couples’ perceptions of men’s ejaculatory behavior. Arch Sex Behav 32: 261–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carani C., Isidori A., Granata A., Carosa E., Maggi M., Lenzi A., et al. (2005) Multicenter study on the prevalence of sexual symptoms in male hypo- and hyperthyroid patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90: 6472–6479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement P., Bernabe J., Gengo P., Denys P., Laurin M., Alexandre L., et al. (2007) Supraspinal site of action for the inhibition of ejaculatory reflex by dapoxetine. Eur Urol 51: 825–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement P., Bernabe P., Gengo P., Roussel D., Giuliano F. (2006) Dapoxetine inhibits p-chloroamphetamine-induced ejaculation in anesthetized rats. Book of Abstracts – 8th Congress of the European Society for Sexual Medicine. J Sex Med 55: abstract P-02-159 [Google Scholar]

- Coupland N., Bell C., Potokar J. (1996) Serotonin reuptake inhibitor withdrawal. J Clin Psychopharmacol 16: 356–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditto K. (2003) SSRI discontinuation syndrome. Awareness as an approach to prevention. Postgrad Med 114: 79–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresser M., Desai D., Gidwani S., Seftel A., Modi N. (2006a) Dapoxetine, a novel treatment for premature ejaculation, does not have pharmacokinetic interactions with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors. Int J Impot Res 18: 104–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresser M., Kang D., Staehr P., Gidwani S., Guo C., Mulhall J., et al. (2006b) Pharmacokinetics of dapoxetine, a new treatment for premature ejaculation: impact of age and effects of a high-fat meal. J Clin Pharmacol 46: 1023–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresser M., Lindert K., Lin D. (2004) Pharmacokinetics of single and multiple escalating doses of dapoxetine in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther 75: 113 (abstract P111). [Google Scholar]

- Gengo P., Marson L., Gravitt A. (2006) Actions of dapoxetine in ejaculation and sexual behaviour in rats. Book of Abstracts – 8th Congress of the European Society for Sexual Medicine. J Sex Med 28: abstract MP-01-074 [Google Scholar]

- Gengo R., Giuliano F., McKenna K., Chester A., Lovenberg T., Bonaventure P., et al. (2005) Monoaminergic transporter binding and inhibition profile of dapoxetine, a medication for the treatment of premature ejaculation. J Urol 173: 230 (abstract 878).15592082 [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano F., Bernabe J., Gengo P., Alexandre L., Clement P. (2007) Effect of acute dapoxetine administration on the pudendal motoneuron reflex in anesthetized rats: comparison with paroxetine. J Urol 177: 386–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano F., Patrick D., Porst H., La Pera G., Kokoszka A., Merchant S., et al. (2008) Premature ejaculation: results from a five-country European observational study. Eur Urol 53: 1048–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godpodinoff M. (1989) Premature ejaculation: clinical subgroups and etiology. J Sex Marital Ther 15: 130–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. (1980) An assessment of clomipramine (Anafranil) in the treatment of premature ejaculation. J Int Med Res 8(Suppl. 3): 53–59 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann U., Schedlowski M., Kruger T. (2005) Cognitive and partner-related factors in rapid ejaculation: differences between dysfunctional and functional men. World J Urol 10: 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzimouratidis K., Amar E., Eardley I., Giuliano F., Hatzichristou D., Montorsi F., et al. (2010) Guidelines on male sexual dysfunction: erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation. Eur Urol 57: 804–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom W., Althof S., Gittelman M., Streidle C., Ho K., Kell S., et al. (2005) Dapoxetine for the treatment of men with premature ejaculation (PE):dose-finding analysis. J Urol 173: 238 (abstract 877).15592086 [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom W., Gittelman M., Althof S. (2004) Dapoxetine HCl for the treatment of premature ejaculation: a phase II, randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled study. J Sex Med 1(Suppl. 1): 59 (abstract 097). [Google Scholar]

- Hyun J., Kam S., Kwon O. (2008) Changes of cerebral current source by audiovisual erotic stimuli in premature ejaculation patients. J Sex Med 5: 1474–1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannini E., Lenzi A. (2005) Epidemiology of premature ejaculation. Curr Opin Urol 15: 399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannini E., Maggi M., Lenzi A. (2011) Evaluation of premature ejaculation. J Sex Med 8(Suppl. 4): 328–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannini E., Simonelli C., Lenzi A. (2002) Sexological approach to ejaculatory dysfunction. Int J Androl 25: 317–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen P., Bakker S., Rethelyi J., Zwinderman A., Touw D., Olivier B., et al. (2009) Serotonin transporter promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism is associated with the intravaginal ejaculation latency time in Dutch men with lifelong premature ejaculation. J Sex Med 6: 276–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong I., Kim S., Yoon S., Hahn S. (2012) Block of cloned Kv4.3 potassium channels by dapoxetine. Neuropharmacology 62: 2261–2266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jern P., Santtila P., Witting K., Alanko K., Harlaar N., Johansson A., et al. (2007) Premature and delayed ejaculation: genetic and environmental effects in a population-based sample of Finnish twins. J Sex Med 4: 1739–1749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara H., Aydin S., Yucel M., Agargun M., Odabas O., Yilmaz Y. (1996) The efficacy of fluoxetine in the treatment of premature ejaculation: a double-blind placebo controlled study. J Urol 156: 1631–1632 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J., Rosen R., Mudumbi R., Tesfaye F., Hashmonay R., Rivas D. (2009) Treatment benefit of dapoxetine for premature ejaculation: results from a placebo-controlled phase III trial. BJU Int 103: 651–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A., Khan S., Kolts R., Brown W. (2003) Suicide rates in clinical trials of SSRIs, other antidepressants, and placebo: analysis of FDA reports. Am J Psychiatry 160: 790–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowey P., Mudumbi R., Aquilina J., Dibattiste P. (2011) Cardiovascular safety profile of dapoxetine during the premarketing evaluation. Drugs R D 11: 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane R. (1997) A critical review of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-related sexual dysfunction; incidence, possible aetiology and implications for management. J Psychopharmacol 11: 72–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann E., Nicolosi A., Glasser D., Paik A., Gingell C., Moreira E., et al. (2005) Sexual problems among women and men aged 40–80 y: prevalence and correlates identified in the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Int J Impot Res 17: 39–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann E., Paik A., Rosen R. (1999) Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA 281: 537–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livni E., Satterlee W., Robey R., Alt C., Van Meter E., Babich J., et al. (1994) Synthesis of [11C]dapoxetine.HCl, a serotonin re-uptake inhibitor: biodistribution in rat and preliminary PET imaging in the monkey. Nucl Med Biol 21: 669–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann J., Emslie G., Baldessarini R., Beardslee W., Fawcett J., Goodwin F., et al. (2006) ACNP Task Force report on SSRIs and suicidal behavior in youth. Neuropsychopharmacology 31: 473–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters W., Johnson V. (1970) Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston, MA: Little Brown, pp. 92–115 [Google Scholar]

- McMahon C. (1998) Treatment of premature ejaculation with sertraline hydrochloride: a single-blind placebo controlled crossover study. J Urol 159: 1935–1938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon C. (2002) Long term results of treatment of premature ejaculation with selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors. Int J Impot Res 14(Suppl. 3): S1912161764 [Google Scholar]

- McMahon C. (2008) Clinical trial methodology in premature ejaculation observational, interventional, and treatment preference studies – part II – study design, outcome measures, data analysis, and reporting. J Sex Med 5: 1817–1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon C., Abdo C., Incrocci L., Perelman M., Rowland D., Waldinger M., et al. (2004) Disorders of orgasm and ejaculation in men. J Sex Med 1: 58–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon C., Althof S., Kaufman J., Buvat J., Levine S., Aquilina J., et al. (2011) Efficacy and safety of dapoxetine for the treatment of premature ejaculation: integrated analysis of results from five phase 3 trials. J Sex Med 8: 524–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon C., Althof S., Waldinger M., Porst H., Dean J., Sharlip I., et al. (2008) An evidence-based definition of lifelong premature ejaculation: report of the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) Ad Hoc Committee for the Definition of Premature Ejaculation. J Sex Med 5: 1590–1606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon C., Kim S., Park N., Chang C., Rivas D., Tesfaye F., et al. (2010) Treatment of premature ejaculation in the Asia-Pacific region: results from a phase III double-blind, parallel-group study of dapoxetine. J Sex Med 7: 256–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon C., Porst H. (2011) Oral agents for the treatment of premature ejaculation: review of efficacy and safety in the context of the recent International Society for Sexual Medicine criteria for lifelong premature ejaculation. J Sex Med 8: 2707–2725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz M., McCarthy B. (2003) Coping with Premature Ejaculation: How to Overcome PE, Please your Partner and Have Great Sex. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications [Google Scholar]

- Metz M., Pryor J. (2000) Premature ejaculation: a psychophysiological approach for assessment and management. J Sex Marital Ther 26: 293–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz M., Pryor J., Nesvacil L., Abuzzahab F., Sr, Koznar J. (1997) Premature ejaculation: a psychophysiological review. J Sex Marital Ther 23: 3–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi N., Dresser M., Desai D., Edgar C., Wesnes K. (2007) Dapoxetine has no pharmacokinetic or cognitive interactions with ethanol in healthy male volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol 47: 315–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi N., Dresser M., Simon M., Lin D., Desai D., Gupta S. (2006) Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of dapoxetine hydrochloride, a novel agent for the treatment of premature ejaculation. J Clin Pharmacol 46: 301–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi N., Kell S., Aquilina J., Rivas D. (2008) Effect of dapoxetine on the pharmacokinetics and hemodynamic effects of tamsulosin in men on a stable dose of tamsulosin. J Clin Pharmacol 48: 1438–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi N., Nath R., Staehr P., Gupta S., Aquilina J., Rivas D. (2009) Pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and electrocardiographic effects of dapoxetine and moxifloxacin compared with placebo in healthy adult male subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 49: 634–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague D., Jarow J., Broderick G., Dmochowski R., Heaton J., Lue T., et al. (2004) AUA guideline on the pharmacologic management of premature ejaculation. J Urol 172: 290–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montejo A., Llorca G., Izquierdo J., Rico-Villademoros F. (2001) Incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant agents: a prospective multicenter study of 1022 outpatients. Spanish Working Group for the Study of Psychotropic-Related Sexual Dysfunction J Clin Psychiatry 62(Suppl. 3): 10–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montorsi F. (2005) Prevalence of premature ejaculation: a global and regional perspective. J Sex Med 2(Suppl. 2): 96–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng G. (2006) Treating patients with ventricular ectopic beats. Heart 92: 1707–1712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolosi A., Laumann E., Glaser D., Moreira E., Paik A., Gingell C. (2004) Global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors investigator’s group. Sexual behavior and sexual dysfunctions after age 40: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors Urology 64: 991–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier B., van Oorschot R., Waldinger M. (1998) Serotonin, serotonergic receptors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and sexual behaviour. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 13(Suppl. 6): S9–S14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastore A., Palleschi G., Leto A., Pacini L., Iori F., Leonardo C., et al. (2012) A prospective randomized study to compare pelvic floor rehabilitation and dapoxetine for treatment of lifelong premature ejaculation. Int J Androl 9 February (epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick D., Althof S., Pryor J., Rosen R., Rowland D., Ho K., et al. (2005) Premature ejaculation: an observational study of men and their partners. J Sex Med 2: 358–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick D., Giuliano F., Ho K., Gagnon D., McNulty P., Rothman M. (2009) The Premature Ejaculation Profile: validation of self-reported outcome measures for research and practice. BJU Int 103: 358–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattij T., Olivier B., Waldinger M. (2005) Animal models of ejaculatory behavior. Curr Pharm Des 11: 4069–4077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peugh J., Belenko S. (2001) Alcohol, drugs and sexual function: a review. J Psychoactive Drugs 33: 223–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porst H., McMahon C., Althof S., Sharlip I., Bull S., Aquilina J., et al. (2010) Baseline characteristics and treatment outcome for men with acquired or lifelong premature ejaculation with mild or no erectile dysfunction: integrated analyses of three phase 3 dapoxetine trials. J Sex Med 7: 2231–2242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porst H., Montorsi F., Rosen R., Gaynor L., Grupe S., Alexander J. (2007) The Premature Ejaculation Prevalence and Attitudes (PEPA) survey: prevalence, comorbidities, and professional help-seeking. Eur Urol 51: 816–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryor J., Althof S., Steidle C., Rosen R., Hellstrom W., Shabsigh R., et al. (2006) Efficacy and tolerability of dapoxetine in treatment of premature ejaculation: an integrated analysis of two double-blind, randomised controlled trials. Lancet 368: 929–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley D., Finkelstein S., Stafford R. (2006) Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med 166: 1021–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland D., McMahon C., Abdo C., Chen J., Jannini E., Waldinger M., et al. (2010) Disorders of orgasm and ejaculation in men. J Sex Med 7: 1668–1686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonia A., Rocchini L., Sacca A., Pellucchi F., Ferrari M., Carro U., et al. (2009) Acceptance of and discontinuation rate from paroxetine treatment in patients with lifelong premature ejaculation. J Sex Med 6: 2868–2877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapiro B. (1943) Premature ejaculation, a review of 1130 cases. J Urol 50: 374–379 [Google Scholar]

- Screponi E., Carosa E., Di Stasi S., Pepe M., Carruba G., Jannini E. (2001) Prevalence of chronic prostatitis in men with premature ejaculation. Urology 58: 198–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segraves R. (2010) Considerations for an evidence-based definition of premature ejaculation in the DSM-V. J Sex Med 7: 672–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semans J. (1956) Premature ejaculation: a new approach. South Med J 49: 353–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serefoglu E., Cimen H., Atmaca A., Balbay M. (2009) The distribution of patients who seek treatment for the complaint of ejaculating prematurely according to the four premature ejaculation syndromes. J Sex Med 7: 810–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serefoglu E., Yaman O., Cayan S., Asci R., Orhan I., Usta M., et al. (2011) The comparison of premature ejaculation assessment questionnaires and their sensitivity for the four premature ejaculation syndromes: results from the Turkish society of andrology sexual health survey. J Sex Med 8: 1177–1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabsigh R., Patrick D., Rowland D., Bull S., Tesfaye F., Rothman M. (2008) Perceived control over ejaculation is central to treatment benefit in men with premature ejaculation: results from phase III trials with dapoxetine. BJU Int 102: 824–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorbera L., Castaner J., Castaner R. (2004) Dapoxetine hydrochloride. Drugs Future 29: 1201–1205 [Google Scholar]

- Symonds T., Roblin D., Hart K., Althof S. (2003) How does premature ejaculation impact a man’s life? J Sex Marital Ther 29: 361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamam L., Ozpoyraz N. (2002) Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: a review. Adv Ther 19: 17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyssen A., Sharma O., Tianmei S., Aquilina J., Vandebosch A., Wang S., et al. (2010) Pharmacokinetics of dapoxetine hydrochloride in healthy Chinese, Japanese, and Caucasian men. J Clin Pharmacol 50: 1450–1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger M. (2003) Towards evidenced based drug treatment research on premature ejaculation: a critical evaluation of methodology. J Impot Res 15: 309–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger M. (2006) The need for a revival of psychoanalytic investigations into premature ejaculation. J Mens Health & Gender 3: 390–396 [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger M. (2007) Premature ejaculation: definition and drug treatment. Drugs 67: 547–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger M., Berendsen H., Blok B., Olivier B., Holstege G. (1998b) Premature ejaculation and serotonergic antidepressants-induced delayed ejaculation: the involvement of the serotonergic system. Behav Brain Res 92: 111–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger M., Hengeveld M., Zwinderman A., Olivier B. (1998a) An empirical operationalization of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for premature ejaculation. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2: 287–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger M., Hengeveld M., Zwinderman A. (1994) Paroxetine treatment of premature ejaculation: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 151: 1377–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]