Abstract

The splenic B cell compartment is comprised of two major, functionally distinct, mature B cell subsets, i.e. follicular mature (FM) and marginal zone (MZ) B cells. Whereas MZ B cells exhibit a robust proliferative response following stimulation with the TLR4 ligand, LPS, FM B cells display markedly delayed and reduced levels of proliferation to the identical stimulus. The current study was designed to identify a potential mechanism(s) accounting for this differential responsiveness. In contrast to the delay in cell cycle entry, FM and MZ B cells exhibited nearly identical LPS-driven alterations in the expression level of cell surface activation markers. Further, both the NFκB and mTOR signaling cascades were similarly activated by LPS stimulation in FM vs. MZ B cells, while inducible activation of ERK and AKT were nearly absent in both subsets. MZ B cells, however, exhibited higher basal levels of pAKT and pS6 consistent with a pre-activated status. Importantly, both basal and LPS activation-induced c-myc expression was markedly reduced in FM vs. MZ B cells; and enforced c-myc expression fully restored the defective proliferative response in FM B cells. These data support a model wherein TLR responses in FM B cells are tightly regulated by limiting c-myc levels thereby providing an important checkpoint to control non-specific FM B cell activation in the absence of cognate antigen.

Keywords: B cells, Lipopolysaccharide, Cell Activation, Signal Transduction, Autoimmunity

INTRODUCTION

Mature splenic B cells can be divided into two subpopulations, follicular mature (FM) and marginal zone (MZ) B cells, based on distinct topographic, phenotypic, gene expression and functional characteristics (reviewed in (1)). FM B cells reside in the follicles of the splenic white pulp, while MZ B cells are located in the marginal zone, a region at the border of the splenic red and white pulp. The MZ is delineated by the MZ sinus and a layer of metallophilic macrophages that express MOMA1, thereby surrounding B cell follicles and T cell areas. This architectural structure contributes to the unique function of the splenic MZ to mount a rapid immune response to blood-borne antigens. Phenotypically, MZ B cells are characterized by high expression of IgM, CD21, CD1d, CD9, whereas they are low/negative for IgD and CD23. In contrast, FM B cells are IgMint, IgDhi, CD21int, CD23pos, CD1dlow and CD9low. Multiple gene products are differentially expressed in these two subsets, including, most notably, effectors within the Notch signaling cascade that are essential for MZ B cell development (2), (3).

Mature B cells are relatively unique among immune cells because they express both germline-encoded TLRs as well as a recombination-dependent, clonally rearranged, antigen-specific B cell antigen receptor (BCR). Functionally, FM B cells fit largely within the adaptive arm of the immune system, which is characterized by memory formation and receptor specificity mediated via antigen specific receptors such as the BCR (4). For full activation, FM B cells require T cell help, and accordingly they are the main players during T-dependent immune responses. In contrast, MZ B cells have been classified as innate immune cells. Their immune response is rapid, independent of direct T cell help and directed against a great diversity of blood-borne organisms utilizing pathogen-specific pattern recognition receptors like toll-like receptors (TLR) in association with stimulation via the BCR.

Consistent with the classification into the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system, MZ B cells exhibit a strong response to the TLR4 ligand, LPS, which promotes cell activation, proliferation, and immunoglobulin production (5, 6). FM B cells, in contrast, are readily activated through BCR stimulation in vitro; yet exhibit markedly delayed and reduced cell cycling following LPS stimulation. Notably, although a range of studies have demonstrated differential responsiveness of FM vs. MZ B cells to TLR ligand engagement (5–7), the molecular events that limit FM B cell proliferation in response to this key signal remain to be defined. Because TLR engagement can lead to a break in B cell tolerance (8, 9), understanding the mechanism(s) behind this differential response may provide insight into the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease.

In the current study, we have addressed this question in detail. We demonstrate that FM B cells exhibit a specific deficit in cell cycle entry, despite exhibiting normal LPS-dependent proximal signaling events, and similar TLR4-induced up-regulation of activation markers. Further, we show that this cell cycle deficit is due to: reduced basal activity within the mTOR signaling cascade; and most notably, insufficient basal and inducible up-regulation of the cell cycle and growth regulator, c-myc. Consistent with this conclusion, enforced expression of c-myc rescued this cell cycle deficit leading to efficient FM B cell cycling in response to LPS. Taken together, our findings suggest that limiting c-myc levels may help to restrict FM B cell activation when TLR ligands are encountered in the absence of antigen receptor signaling.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6, c-myc tg (10), MyD88−/− (11), TRIF−/− (12) and (all on a C57BL/6 background) were bred and maintained in the SPF animal facility of the Seattle Children’s Hospital Research Institute (Seattle, WA) and handled according to IACUC approved protocols. Mice used in all experiments were between 6 and 16 weeks of age.

Reagents and antibodies

Antibodies used in this study included reagents specific for: CD24 (M1/69), CD21 (7G6), TNP (49.2) and B220 (RA3-6B2) from BD Pharmingen; CD23 (B3B4) from Caltag; CD62L (MEL-14) from eBiosciences; IgD (11–26) and IgM (1B4B1) from Southern Biotechnology Associates; and CD19 (ID3) from BioLegend. Polyclonal F(ab)2 anti-IgM for BCR stimulation was purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch. Additional reagents included: PyroninY and DAPI from Molecular Probes; LPS from Sigma, BAFF from Alexis and TNP-Ficoll from Biosearch Technologies.

Cell culture

Splenocytes were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS, 55µM 2-ME, 10 mM HEPES, penicillin and streptomycin (complete media) at 37°C. Cells were stimulated with polyclonal goat anti-mouse IgM F(ab)2 fragment or LPS in concentrations as indicated

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Single cell suspensions from BM and spleen were incubated with fluorescently-labeled antibodies for 20 min at 4° C in staining buffer (PBS w/ 0.5% BSA or 2.5% FCS). Data was collected on a FACSCalibur or LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar Inc., Ashland, OR). For LSR II experiments, the data was analyzed using biexponential transformation function for complete data visualization.

For cell sorting, CD43 depletion was performed using magnetic bead-conjugated anti-CD43 Abs according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotech), and enriched cells were labeled with specific antibodies in staining buffer. Sorting was performed using a FACS Aria sorter with Diva software (BD Biosciences). FM B cells were sorted as CD21int, CD24int and MZ B cells as CD21hi, CD24hi, CD23− cells. Due to the limited number of MZ B cells obtainable from murine spleen, CD21hi, CD24hi, CD23+ precursor MZ (MZp) B cells were pooled with MZ B cells for some studies as indicated. Sort purities were >95% for FM B cells and >90% for MZp/MZ or MZ B cells.

3H Thymidine uptake proliferation assay

Purified cells were incubated at 5×104 cells per well in complete media. Cells were pulsed with 1 µCi 3H-thymidine 8 hr prior to harvesting. 3H-thymidine incorporation was measured in triplicate wells using a TopCount Scintillation Counter (PerkinElmer).

CFSE labeling

Sorted B cell subsets were incubated with 0.05µM CFSE at 37°C for 8 min, washed 3 times with complete media, and simulated as indicated. Proliferation was determined by dilution of CFSE 48 or 72 hr post-stimulation.

Cell cycle analysis

For cell cycle analysis, sort purified FM or MZp/MZ B cells were stimulated for indicated periods and fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol. Cells were then incubated for 30 min with 1µg/ml DAPI (Molecular Probes) in PBS with 0.1% BSA and 0.1% Triton-X100. 1.5µg/ml PyroninY (Molecular Probes) was added immediately prior to analysis.

Real-time PCR

Sorted B cell populations were pelleted and frozen at −80 °C. RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) and converted into cDNA by reverse transcriptase (Superscript II, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR using cDNA was performed using the iCycler real-time PCR detection system with IQ SYBR Green Supermix (Biorad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Ratios were calculated using the Pfaffl’s mathematical model for relative quantification (13) with mouse β-2-microglobulin as housekeeping control. All real-time PCR analyses shown include combined data from at least 3 independent experiments. Primer sequences used include:

c-myc 5’-TCTCCACTCACCAGCACAACTACG, c-myc 3’-

ATCTGCTTCAGGACCCT, b2m 5’-TAACACAGTTCCACCCGCCTCA, b2m 3’-

GCTCGGCCATACTGTCATGCTT, A1 5’- CCTGGCTGAGCACTACCTTCA,

A1 3’-CTGCATGCTTGGCTTGGA, Bcl-xL 5’-CTGGGACACTTTTGTGGATCTCT,

Bcl-xL 3’-GAAGCGCTCCTGGCCTTT, AICDA 5’-

TGAGGGAGTCAAGAAAGTCACGC, AICDA 3’-

AGAGGTAGGTCTCATGCCGTCC, BAFF-R 5’-AATCAGACCGAGTGCTTCGACC,

BAFF-R 3’-CAGCGCGGAGCCCTCCT

Ca2+ flux

Splenic B cells were incubated with Indo-1 (10 µg/ml, Molecular Probes) for 30 min at 37°C and then surface stained with antibodies to B220, CD24, CD21 and IgM (non-stimulatory Fab fragment). Cells were washed and stimulated with a stimulatory anti-IgM antibody or LPS, and Ca2+ flux was measured by flow cytometry within each B cell subset.

Western blot analysis

For whole cell lysates, stimulated B cells were lysed at indicated time points in a buffer containing 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% Triton X-100, 250mM NaCl, 50mM Tris (pH7.5), sodium ortho-vanadate and protease inhibitors (NaCl was increased to 500mM for c-myc blots). Nuclear extracts were prepared by cell lysis with a buffer containing 10mM HEPES 7.9, 10mM KCL, 0.1mM EDTA, 1mM DTT, 0.5% NP-40 and protease inhibitors; followed by high-speed centrifugation (10min). Pelleted nuclei were subsequently lysed in buffer containing 20mM HEPES 7.9, 0.5M NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 10% Glycerol, 1mM DTT and protease inhibitors, spun at maximum speed for 10 min and the supernatant (nuclear lysate) was utilized for western blotting. Lysates were run on a 10% SDS gel, transferred to a PVDF-FL membrane (Millipore) and blots were probed with anti-IκBα (SC-203), c-Rel (SC-71), p65 (SC-372-G), pERK (SC-7383), ERK1 (SC-93), HDAC1 (SC-6298), c-myc (SC-764) (all from Santa Cruz) and/or pS6 (Cell Signaling #2211S) antibodies.

Flow cytometry analysis of pAKT

Splenic B cells were incubated in RPMI with 10% FCS for 30 min, stimulated with 15 µg/ml polyclonal goat F(ab)2 fragment, anti-mouse IgM or 20 µg/ml LPS and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were then surface stained with antibodies to B220, CD21, CD24 CD23, permeabilized with permwash (BD Pharmingen) for 20 min at 4°C, and incubated with unconjugated anti-phospho-AKT-Ser473 antibody (Cell Signaling) for 45 min at room temperature, followed by anti-rabbit Alexa488 (Jackson Immunolaboratories).

Inhibitor studies

The PI3K inhibitors, Wortmannin (Sigma) and the mTOR inhibitor, Rapamycin (Sigma), were used at 100 nM. Cells were pre-incubated with inhibitors for 60 min prior to stimulation.

In vitro analysis of antibody production

Sort purified FM or MZp/MZ cells were plated at ~150,000 cells per well in 96-well plates and stimulated with 20ug/ml LPS, Culture supernatants were collected at day 3, diluted 1:100 in PBS, incubated in triplicate on anti-IgM (10ug/ml) coated, washed and followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. ELISA was performed using TMB ELISA kit (BD Bioscience) and absorbance was measured at 450nm on a Victor 3 plate reader (Perkin Elmer). IgM levels were quantified using titrated standards.

TNP-Ficoll binding assay

Mice were injected i.v. with 500µl 1mg/ml TNP-Ficoll. 30 min later splenocytes were isolated from injected mice, surface stained with B220, CD21 and CD24, and TNP-Ficoll binding was determined in each B cell subset using an anti-TNP antibody.

Statistical evaluation

P-values were calculated using the Student’s t-test.

RESULTS

Limited cell cycle entry of FM B cells in response to LPS

It has previously been shown that FM B cells proliferate only weakly, if at all, to LPS stimulation (5, 6, 14). Using a tritiated-thymidine proliferation assay, BCR stimulation of sort purified FM B cells results in rapid thymidine incorporation within 48 hr of stimulation. The identical population, however, exhibits a negligible response to stimulation across a broad range of LPS doses (Fig. 1A and data not shown). In contrast, MZ B cells exhibit a rapid and robust proliferative response to LPS; but undergo apoptosis in response to BCR engagement in vitro. Sort purities in these and all subsequent experiments were >95% and >90% for FM and MZ B cells, respectively. The near absence of FM proliferation in response to LPS differs from some previous reports, and likely reflects higher FM B cell purity in our studies. Similar results were also obtained by analyzing dilution of CFSE: 48 hr after LPS stimulation MZ B cells have undergone 1–2 divisions, while very few FM B cells exhibit CFSE dilution in response to this stimulus even at very high doses (up to 50µg/ml; Fig. 1B). Analysis at 72 hr demonstrates that a subset of FM B cells have divided to a similar extent as MZ B cells. However, whereas nearly all MZ B cells had divided at least once in response to 1 or 10 µg/ml LPS, even at 50 µg/ml LPS a significant proportion of FM B cells (10–15%) consistently fail to enter cell cycle.

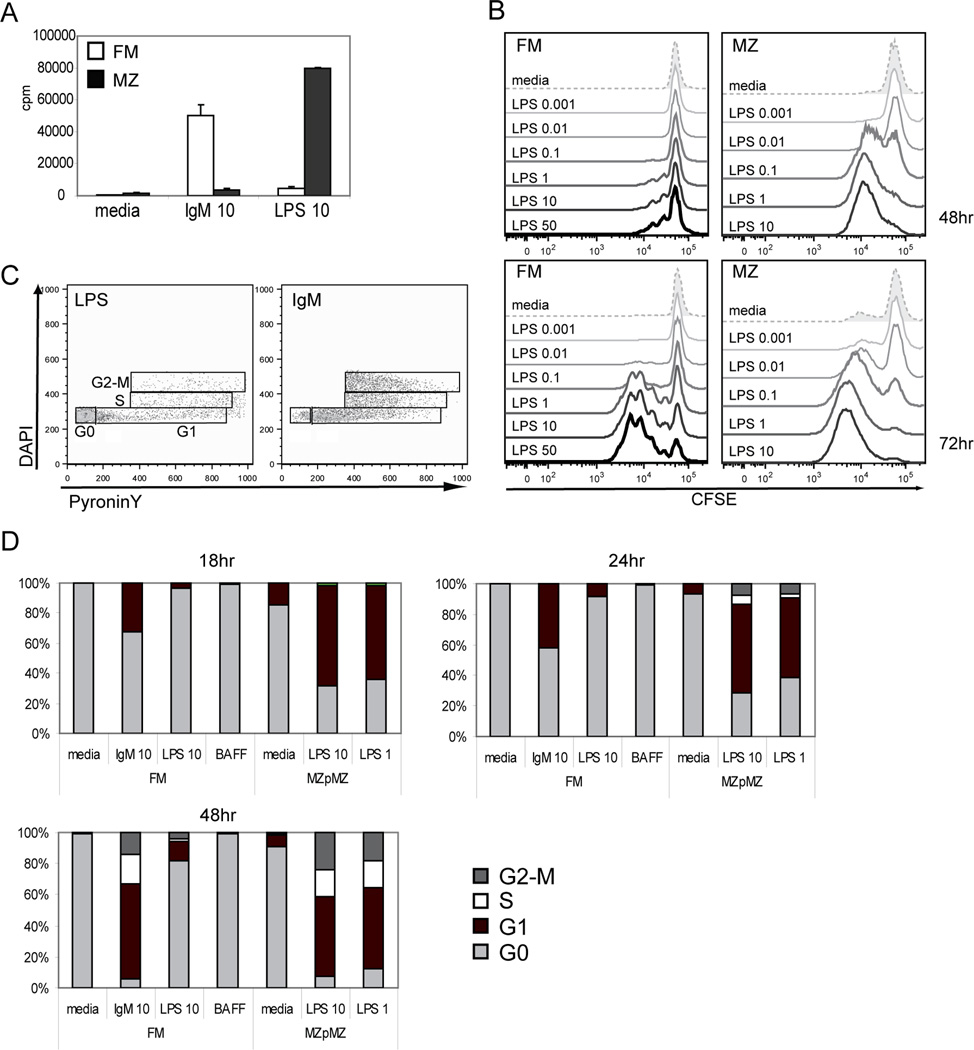

Figure 1. Delayed cell cycle entry of FM B cells in response to LPS.

A. Sort purified FM and MZ B cells were stimulated with media alone, or 10 µg/ml of anti-IgM or LPS for 48 hr, followed by measurement of 3H-thymidine incorporation. Data shown are representative of >5 independent experiments. B. Stimulation of sort purified, CFSE labeled FM and MZ B cells with varying doses of LPS (0.001 –10 µg/ml). Dilution of CFSE was analyzed at 48hr or 72 hrs as indicated. C–D. Cell cycle analysis of stimulated FM vs. MZp/MZ B cells. C. Example of staining and gating strategy using PyroninY and DAPI to assess FM B cells stimulated for 48 hr with either 10 µg/ml of anti-IgM or LPS as indicated. D. Cell cycle status at different time points in FM vs. MZp/MZ B cells following stimulation with anti-IgM, LPS or, 50 ng/ml BAFF, as indicated. Data shown are representative of one of 3 independent experiments.

We also performed FACS-based cell cycle analysis in anti-IgM vs. LPS stimulated mature B cell subsets. To obtain sufficient numbers of MZ lineage cells, we carried out this analysis using sorted cells comprised of both MZ precursors (MZp), a subset that exhibits a nearly identical response to LPS, as well as MZ B cells (7, 15). While FM B cells rapidly entered cell cycle in response to BCR ligation, very few cells entered G1-phase even 48 hr after LPS stimulation (Fig. 1C–D). In contrast, LPS stimulated MZp/MZ B cells rapidly entered cell cycle, resembling the response of FM B cells to BCR engagement. As an additional control, incubation with BAFF promoted survival of FM B cells but did not promote cycling with or without LPS stimulation (Fig. 1D and data not shown). Together, these data demonstrate that FM B cells have a marked delay or block in cell cycle entry in response to LPS stimulation.

FM B cells are highly sensitive to LPS stimulation

Based on these observations, we next asked whether FM B cells exhibit a global defect in response to LPS signaling. Consistent with this idea, previous studies have shown that the TLR4 co-receptor, RP105, is expressed at significantly higher levels on MZ compared to FM B cells; suggesting that this difference might impact the overall LPS responsiveness of FM B cells. As an initial test of the sensitivity of FM B cells to LPS, purified FM vs. MZp/MZ B cells were stimulated with varying doses of LPS and the relative expression level of a series of activation markers was determined by FACS (Fig. 2A–B). Most activation markers including CD86, CD25, MHC II, and PNA were expressed at higher levels basally in unstimulated MZp/MZ compared to FM B cells. LPS stimulation, however, led to a similar fold change in each of these activation markers in both cell types at 48 hr post stimulation. FM B cells also consistently up-regulated CD23 expression even at very low doses of LPS. This marker is not expressed on MZ B cells and therefore not evaluated in that population. Alteration in surface markers was dependent upon expression of the TLR signaling adaptors, MyD88 and TRIF, consistent with a direct role for LPS signals in modulating their expression (data not shown). Notably, like MZp/MZ cells, FM B cells readily responded to LPS doses as low as 0.1µg/ml. However, at these lower LPS doses, MZp/MZ B cells showed relatively greater responses indicating that they are slightly more sensitive to LPS.

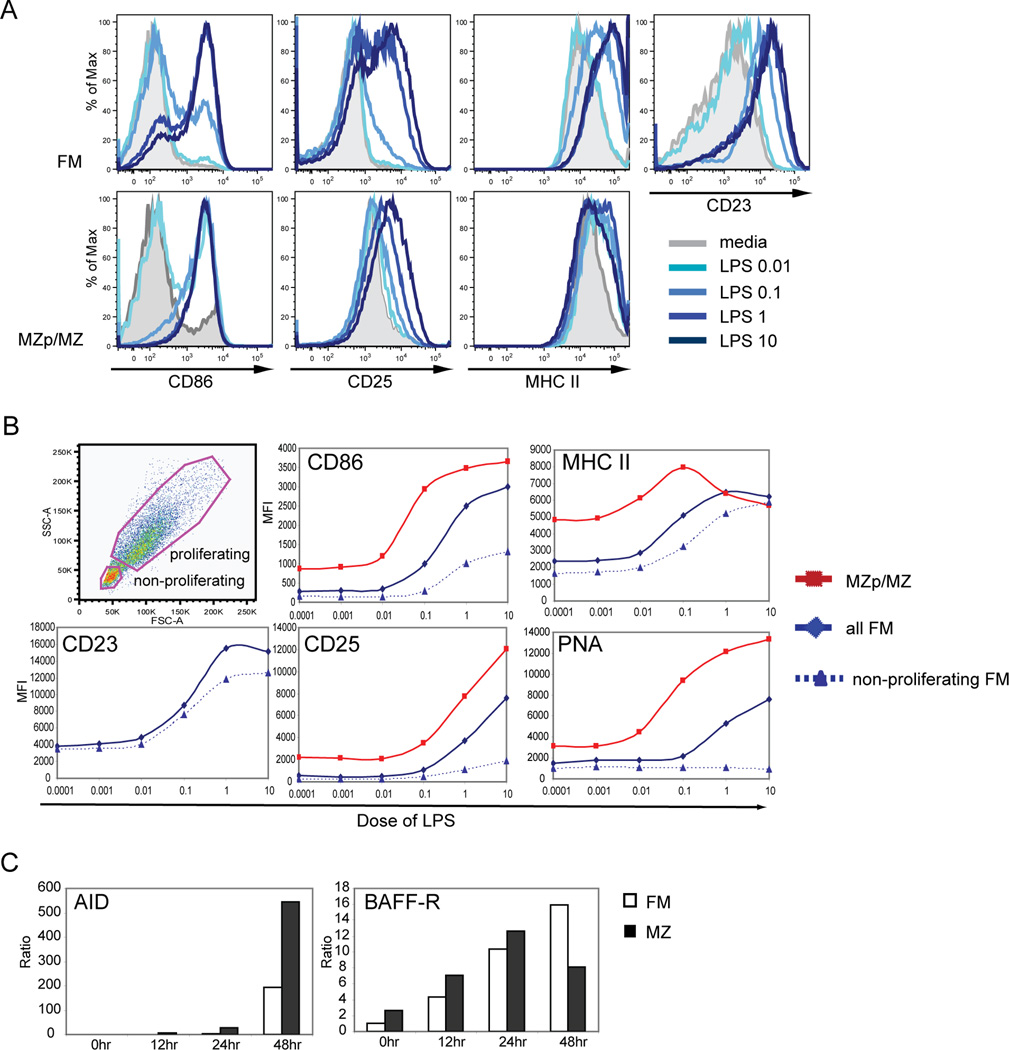

Figure 2. FM B cells are highly sensitive to LPS stimulation.

A–B. Expression of cell surface activation markers at 48 hr in response to varying doses of LPS on sort purified FM vs. MZp/MZ B cells. A. FACS histograms of stained cells. B. Example of gating strategy to identify non-proliferating vs. proliferating FM B cells (upper panel) and the dose-response curves for marker expression on FM vs. MZp/MZ B cells at 48 hr post stimulation. C. Expression of AID and BAFF-R transcript levels as determined by quantitative PCR in stimulated FM vs. MZ B cells at time points indicated. All data shown are representative of one of at least 3 independent experiments.

We also compared the relative expression of candidate activation markers in non-proliferating versus total FM B cells (identified based on relative size and forward scatter as shown in Fig 2B) at 48 hr post LPS stimulation. Whereas CD25 and PNA were nearly exclusively up-regulated in enlarged FM B cells, MHC II and CD23 were equivalently up-regulated in both proliferating and non-proliferating FM B cells (Fig. 2B). CD86 was also up-regulated in non-proliferating FM B cells although to a slightly lesser extent than in the proliferating population.

In addition, we directly compared the kinetics of candidate LPS target genes by assessing mRNA expression levels for AID and BAFF-R, in response to LPS stimulation in FM vs. MZ B cells. Although LPS-induced AID expression was higher in MZ B cells, significant expression was achieved only after 48hr; and this timing was similar to that observed for FM B cells (Fig. 2C). Basal BAFF-R transcript expression levels were slightly higher in MZ B cells. However, BAFF-R mRNA induction was nearly identical with regard to kinetics and maximal expression levels up to 24 hr post stimulation in FM vs. MZ B cells.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that although FM B cells are highly sensitive towards LPS stimulation as assessed by activation marker and target gene expression, this subset exhibits a clear deficit in cell cycle entry and proliferation in response to LPS.

FM and MZ B cells exhibit similar proximal biochemical responses to LPS stimulation

Based upon our findings, we next sought to determine why FM B cells failed to enter cell cycle at early time points following LPS stimulation. To begin to address this question, we analyzed proximal signaling cascades triggered in response to TLR4 ligation in FM vs. MZp/MZ B cells.

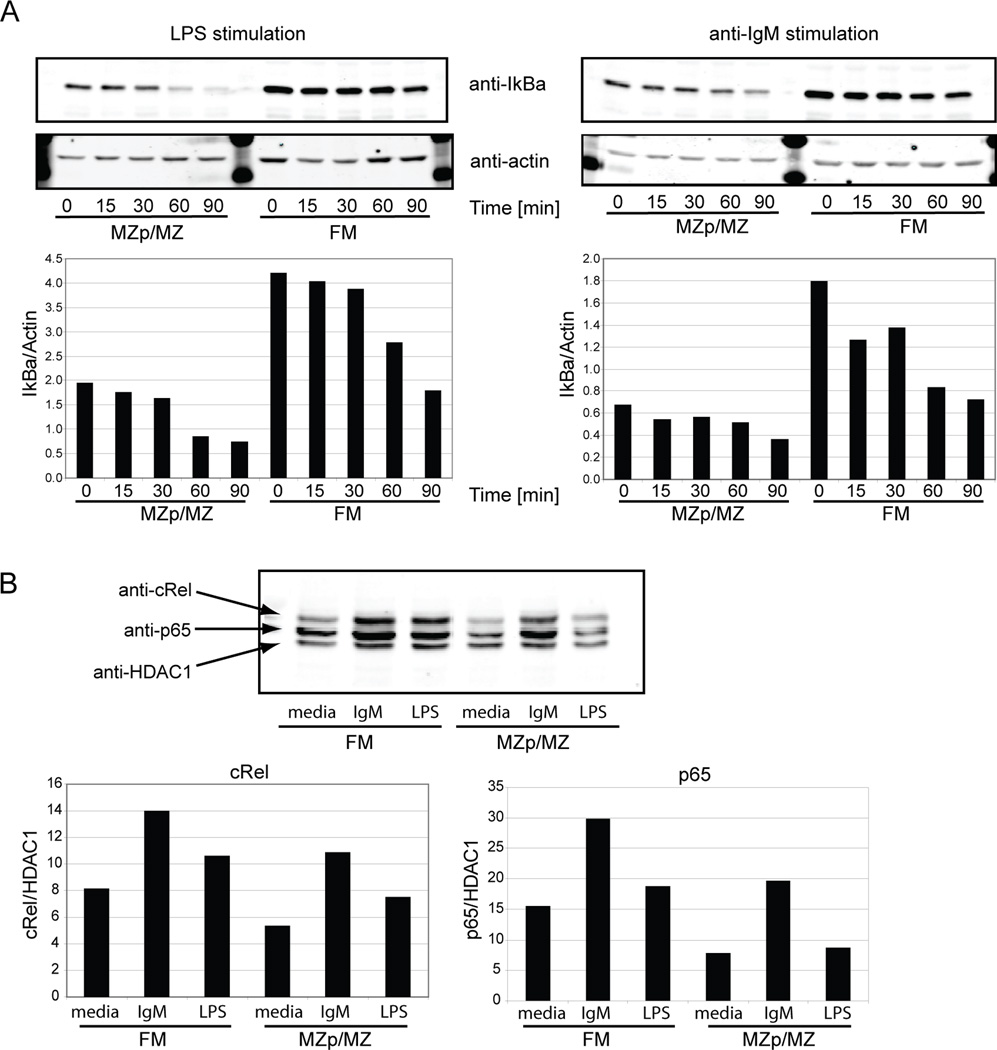

First, we measured activation of the NFκB pathway as assessed by relative degradation of IκBα, a repressor of NFκB nuclear translocation and activity; and nuclear translocation of the NFκB subunits p65 and c-rel. Basal IκBα levels were higher in FM compared to MZp/MZ B cells (Fig. 3A) consistent with the suggestion that basal, canonical NFκB signaling may be greater in the MZp/MZ population (16, 17). However, the relative rate of IκBα degradation following stimulation with either 20µg/ml LPS or 10 µg/ml anti-IgM was similar in both subsets. Moreover, nuclear translocation of p65 and c-rel were comparable in these subsets (Fig. 3B). While activation marker changes were clearly evident, we were unable to identify IκBα degradation following stimulation with lower doses of LPS (e.g. 1µg/ml) in either FM or MZp/MZ B cells (data not shown).

Figure 3. LPS stimulation promotes similar kinetics for both IκBα degradation and cRel and p65 nuclear translocation in FM and MZp/MZ B cells.

A. IκBα degradation in sort purified FM vs. MZp/MZ B cells stimulated with 20 µg/ml LPS or anti-IgM, respectively. Actin was used as loading control. All data shown are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. B. Nuclear extracts from sort purified FM and MZp/MZ B cells stimulated for 3 hr with media alone, 20 µg/ml anti-IgM or LPS, respectively were probed with anti-c-rel and anti-p65 to determine nuclear translocation. HDAC1 was used as loading control. Data were quantified using the Licor system and the IκBα/actin, c-Rel/HDAC1 or p65/HDAC1 ratios were determined and shown as indicated. Data shown are representative of one of two independent experiments.

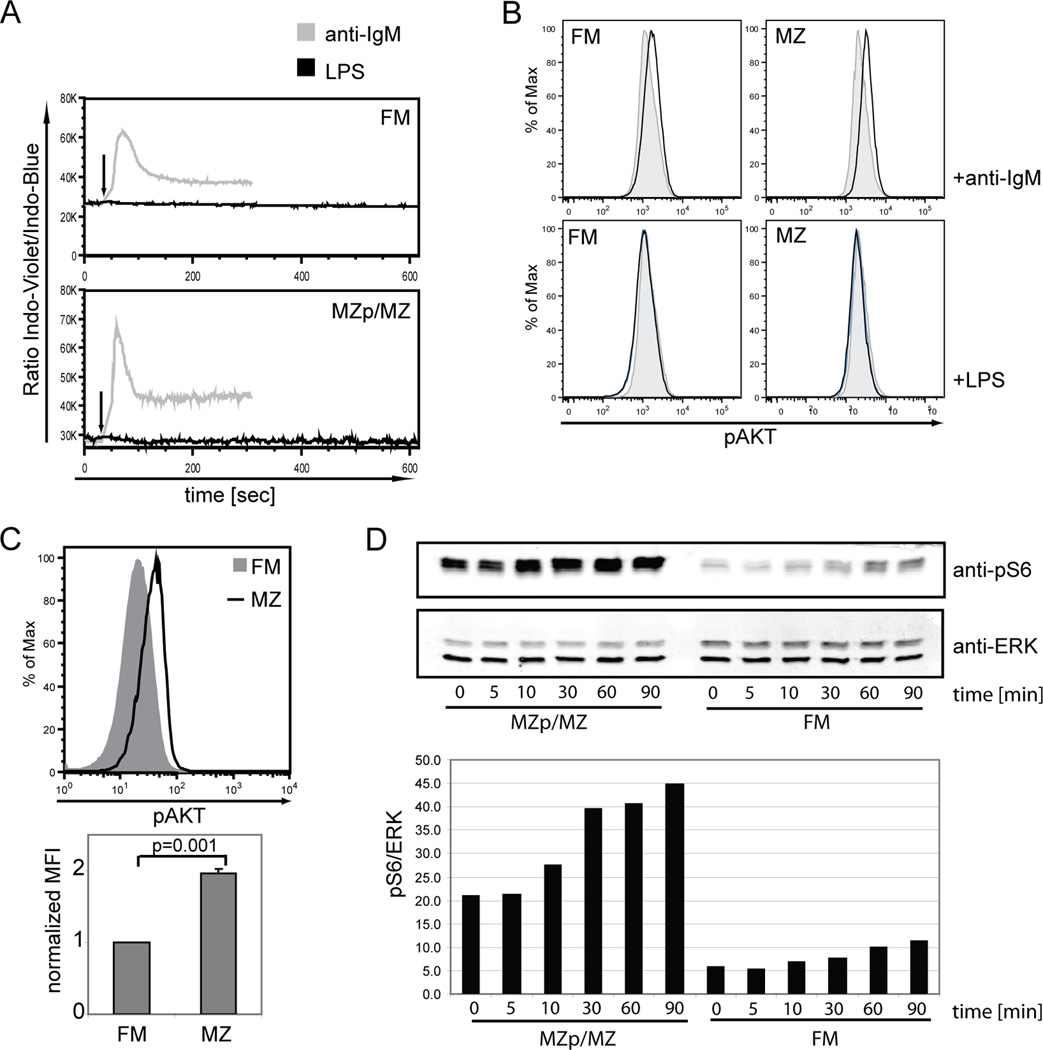

We next investigated Ca2+-flux and signaling via the PI3K pathway. While we observed a clear anti-IgM induced Ca2+-flux, LPS stimulation did not result in Ca2+-flux in either MZp/MZ or FM B cells (Fig. 4A). Phosphorylation of AKT was evaluated using a FACS based assay. Consistent with a previous report (18), basal pAKT levels were ~2-fold higher in MZp/MZ compared to FM B cells (Fig. 4C). As anticipated, BCR engagement resulted in rapid phosphorylation of AKT in both populations. In contrast, stimulation with LPS failed to induce any increase in pAKT in either FM or MZp/MZ B cells for up to 20 min post stimulation (Fig. 4B and data not shown).

Figure 4. Calcium2+ flux and PI3K and mTOR signaling cascades following TLR4 engagement.

A. Total CD43-depleted splenic B cells were loaded with Indo-1, surface stained and stimulated with 20 µg/ml anti-IgM or LPS (arrow). Ca2+ flux within each mature B cell subset was measured by flow cytometry. B. Phosphorylation of AKT was determined in FM vs. MZp/MZ B cells at 2 min post-stimulation with 20 µg/ml anti-IgM or LPS, respectively. C. Determination of basal levels of pAKT in unstimulated FM and MZ B cells by FACS (upper panel) and average of MFI from 3 independent experiments (lower panel) p=0.001. D. Phosphorylation of S6 in sort purified FM vs. MZp/MZ B cells stimulated with 20 µg/ml LPS for different periods of time as indicated. ERK was used as loading control. Data were quantified using the Licor system and the pS6/ERK determined

Recent work has suggested that the mTOR pathway is activated via PI3K-independent signals in response to LPS (18). Therefore, we also analyzed mTOR activation by determining relative phosphorylation of the ribosomal protein S6. Basal levels of pS6 were significantly higher in MZp/MZ B cells and this phosphorylation was further enhanced in response to TLR4 engagement. FM B cells, however, exhibited an equivalent fold-increase in S6 phosphorylation following LPS stimulation (~2-fold) demonstrating that this pathway was also similarly activated in this population (Fig 4D–E). We were also unable to demonstrate a significant change in S6 phosphorylation following low-dose LPS stimulation in either population (data not shown), consistent with the idea that these subsets are not markedly different with regard to these biochemical responses.

We next assessed ERK signaling as this pathway plays a key role in cell growth in response to a range of cell surface receptors. Consistent with previous data (19), stimulation with LPS resulted in weak phosphorylation of ERK at late time points (10–30 min) relative to BCR stimulation. This analysis again failed to reveal any major difference in these signals in FM vs. MZp/MZ B cells (data not shown).

While proximal LPS driven signals have been extensively studied in other cell types, analyses using primary B cells have been more limited. Our combined findings indicate that LPS strongly promotes activation of the NFκB and mTOR pathways, fails to activate calcium or PI3K signaling, and promotes delayed ERK activation. Surprisingly, despite the failure to enter cell cycle, FM B cells exhibit no appreciable deficit in these proximal signals following TLR4 ligation.

Basal mTOR signaling in MZ B cells facilitates the proliferative response to LPS

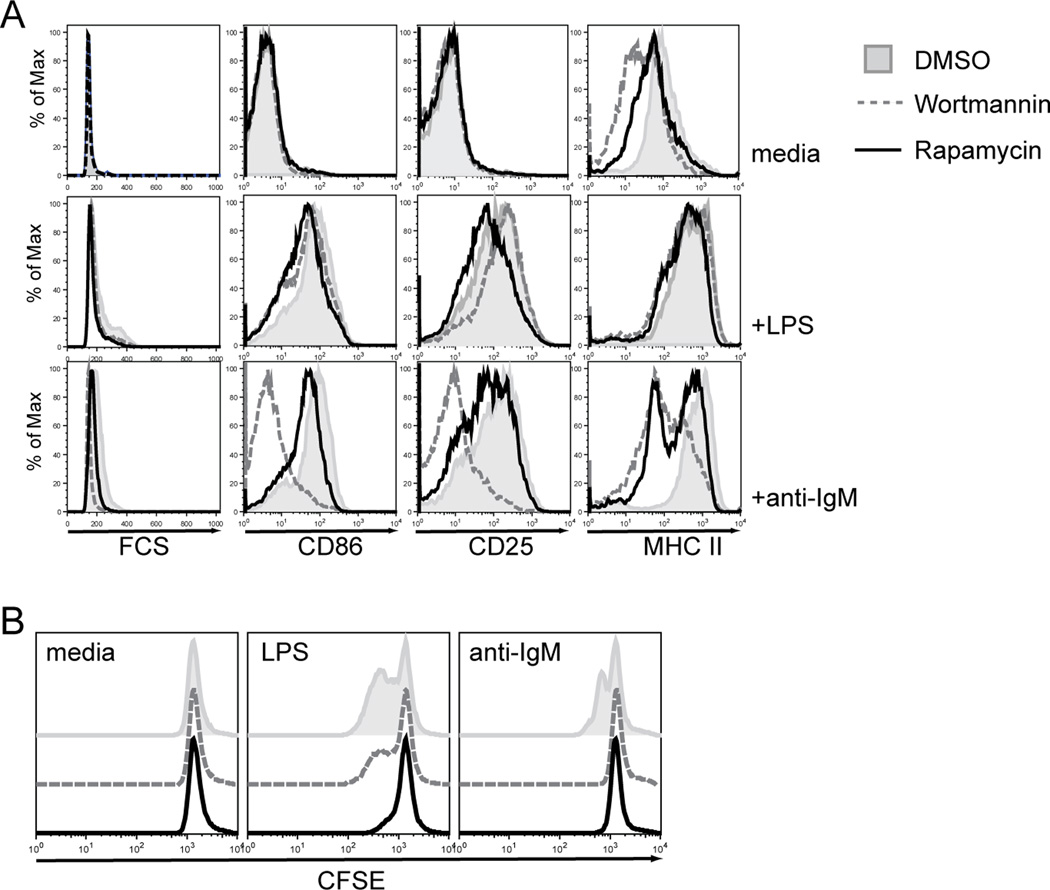

Because we failed to observe major differences in proximal LPS-driven signals, we next asked whether the differential capacity for cycling might reflect key differences in the basal activation status of FM vs. MZ B cells. While the PI3K/AKT pathway plays a crucial role in cell proliferation, it is not directly activated upon LPS stimulation as shown above. Thus, if the increased basal PI3K/AKT signals permitted LPS-driven cycling in MZp/MZ B cells, blocking these signals should limit LPS-triggered proliferation, but not alter the capacity to up-regulate activation markers. To test this idea, we treated total splenic B cells using either the PI3K-specific inhibitor, Wortmannin, or the mTOR-specific inhibitor, Rapamycin. Cells were pre-treated with inhibitor (or DMSO as control) for 1hr and subsequently stimulated with LPS or anti-IgM. Cell survival was minimally effected with either inhibitor at the doses used (not shown). In anti-IgM stimulated cells, Wortmannin treatment lead to near complete ablation of up-regulation of all activation markers, whereas Rapamycin mainly altered MHC II levels (Fig. 5A). BCR-induced proliferation was abrogated in response to either inhibitor (Fig. 5B). In contrast, after LPS stimulation, up-regulation of CD86, CD25 and MHC II were minimally impacted by either inhibitor (Fig. 5A). However, LPS-induced proliferation was completely abrogated by Rapamycin and only minimally impacted by Wortmannin treatment (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Activation of the mTOR pathway is crucial for B cell proliferation but not up-regulation of activation markers in response to LPS.

A. Splenic B cells were pre-treated with Wortmannin, Rapamycin (both at 100 nM) or DMSO for 1hr and subsequently stimulated with 10 µg/ml anti-IgM or LPS. Expression of activation markers was determined after 24 hr. B. CFSE labeled splenic B cells were pre-treated with Wortmannin, Rapamycin or DMSO for 1hr and subsequently stimulated with 10 µg/ml anti-IgM or LPS, respectively. Dilution of CFSE was analyzed after 48hrs. Representative data from one out of 3 independent experiments is shown.

These data imply that proliferation in response to LPS, but not up-regulation of activation markers, is mTOR dependent. Moreover, in contrast to BCR ligation, activation of the mTOR pathway in response to LPS is mainly PI3K-independent. These data also show that high basal and/or triggered mTOR signals are crucial for the LPS-driven proliferative response in MZ B cells.

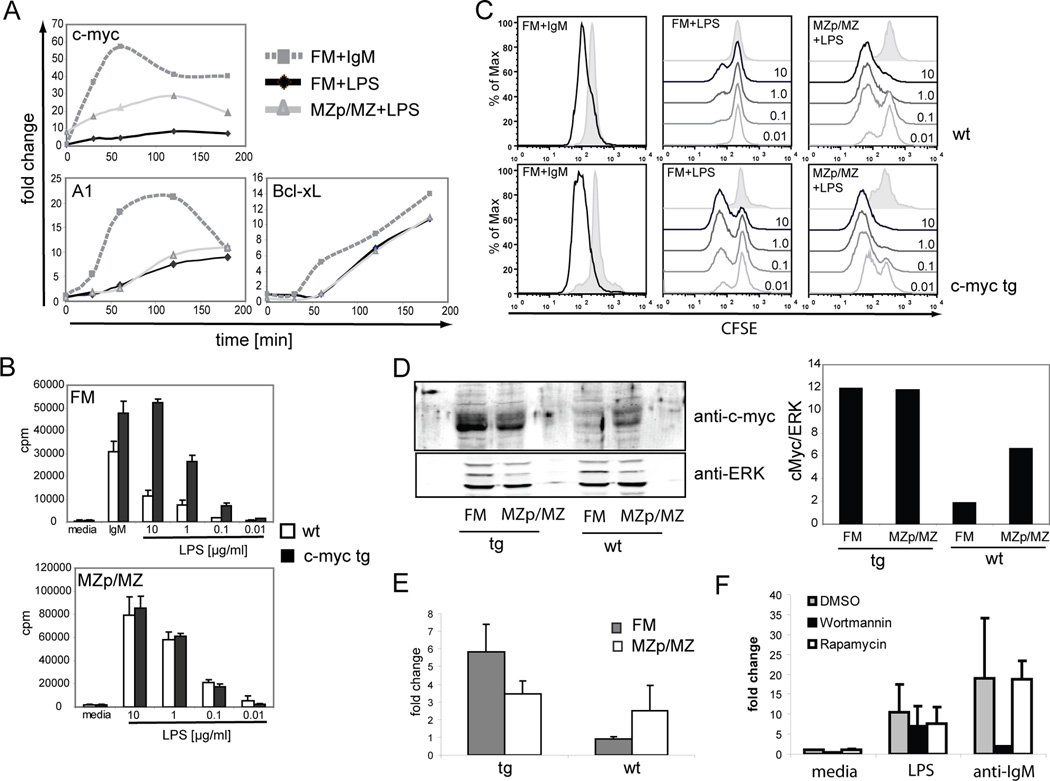

c-myc expression levels limit LPS proliferative responses in FM B cells

NFκB target genes, including c-myc, A1 and Bcl-xL, play a crucial role in BCR and TLR triggered cell survival and proliferation (20–22). Therefore, we next investigated the expression of NFκB target genes in these cell subsets. In unstimulated, freshly isolated FM B cells, c-myc transcript levels were consistently 3-4-fold lower compared to those in MZp/MZ B cells (Fig. 6A, D–E). In contrast, basal A1 and Bcl-xL levels were relatively similar; and LPS stimulation promoted nearly identical kinetics and absolute fold changes for both transcripts in both cell populations. Importantly, while the relative fold-change in c-myc levels were similar or even greater at each time point in FM B cells, absolute c-myc transcript levels remained significantly lower at all time points in this population (Fig 6A). Anti-IgM stimulation of FM B cells resulted in higher levels of all three transcripts, and the rate of increase, and the overall level, of c-myc transcripts was markedly higher compared with LPS stimulated FM B cells.

Figure 6. Basal c-myc levels are markedly lower in FM B cells, but similarly up-regulated in FM vs. MZp/MZ B cells in response to LPS.

A. Sort purified FM and MZp/MZ B cells were stimulated with 20 µg/ml anti-IgM or LPS, respectively and expression of c-myc, A1, and Bcl-xL transcripts were determined by Q-PCR at indicated time points. B–C. 3H-thymidine incorporation and CFSE dilution assays for FM vs. MZp/MZ B cells isolated from wt vs. c-myc tg mice and stimulated with 10 µg/ml anti-IgM or different doses of LPS for 48 hr, respectively. D. Determination of c-myc protein levels in FM vs. MZp/MZ isolated from wt or c-myc tg mice by western blot analysis. ERK is used as a loading control. Western blot data were quantified using the Licor system and c-myc/ERK ratio determined. Data shown are from one of 3 independent experiments. E. c-myc transcript levels were determined in sort purified FM and MZp/MZ B cells from wt (n=3) and c-myc tg (n=4) mice by Q-PCR and data are shown as average with standard deviation. F. Splenic B cells were incubated with Wortmannin and Rapamycin (or DMSO) for 1hr prior to stimulation with 10µg/ml anti-IgM or LPS. Expression of c-myc was determined 3hr later by real-time PCR. Shown is the average of two independent experiments with SD.

Because c-myc is a key regulator for cell proliferation (reviewed (23)), these data suggested that failure to reach a threshold level of c-myc might represent a rate-limiting bottleneck in LPS dependent FM B cell cycling. Further, these data suggested that increasing c-myc dosage might rescue this proliferative defect. To test this idea, we sort-purified FM vs. MZp/MZ B cells from c-myc tg mice and stimulated these cell populations with anti-IgM or LPS. As shown in Figure 6B–C, c-myc tg FM B cells unlike wt cells, exhibited a robust, dose-dependent LPS-driven proliferative response as assessed by either 3H-Thymidine incorporation or CFSE dilution. In contrast, the proliferative response to BCR engagement was only slightly enhanced in c-myc tg FM B cells; and we observed no significant difference in LPS-driven cycling in c-myc tg vs. wt MZp/MZ B cells (except at very low-doses of LPS stimulation). Of note, increased c-myc expression alone, however, was not sufficient to trigger cycling as shown by the dependence for cell cycling on LPS dosage.

We also assessed relative c-myc levels in FM and MZp/MZ B cells from wt and c-myc tg mice using western blotting and semiquantitative real-time PCR. In wt mice, c-myc protein expression was ~3–4 fold higher in MZp/MZ B cells compared to FM B cells and this correlated with ~3-fold higher levels of c-myc mRNA in MZp/MZ cells (Fig 6D–E). FM B cells from c-myc tg mice expressed ~4–6 fold higher levels of c-myc compared to wt FM B cells. These data correlated with a similar increase in c-myc mRNA and rescue of the LPS-driven proliferative response. In contrast, c-myc protein and mRNA levels were minimally increased (<2-fold) in myc-tg MZp/MZ B cells and correlated with the minimal change in proliferative responses to LPS.

Finally, we asked whether increased c-myc expression in MZ B cells might correlate with increased basal mTOR signaling. To address this question, we determined whether PI3K or mTOR signals were required for c-myc up-regulation in response to mitogen stimulation.. Total splenic B cells were incubated with Wortmannin or Rapamycin prior to stimulation with anti-IgM or LPS, and c-myc expression determined by Q-PCR analysis. Neither drug inhibited c-myc expression in response to LPS (Figure 6F). In contrast, c-myc levels after stimulation with anti-IgM were significantly decreased by Wortmannin but not Rapamycin treatment. These results suggest that c-myc upregulation is not linked to the mTOR pathway.

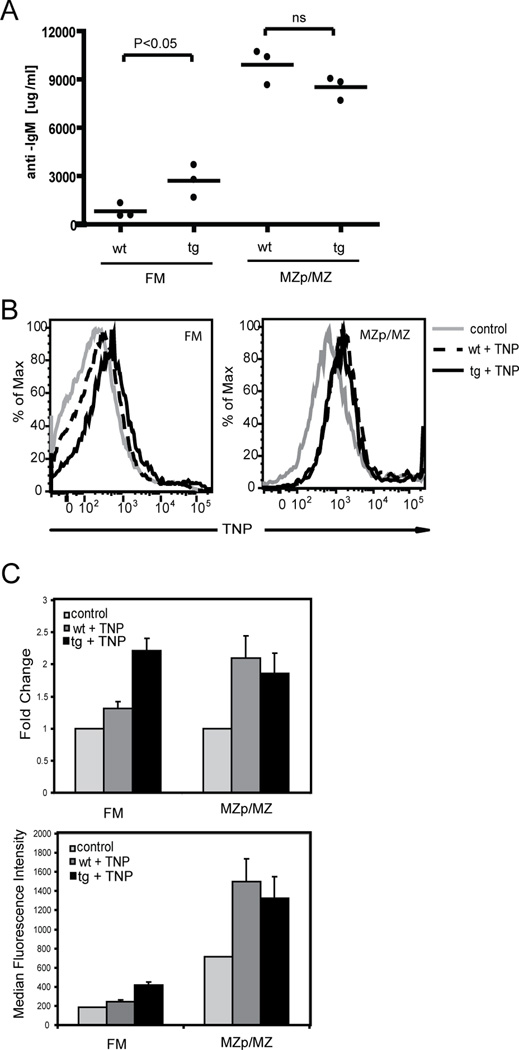

c-myc tg FM B cells exhibit partial T cell independent immune responses

Because over-expression of c-myc in FM B cells leads to functional responses similar to those present in MZ B cells, we next asked whether this change was sufficient to promote participation in T cell independent immune responses. To begin to address this question, we sort-purified FM vs. MZp/MZ B cells from wt and c-myc tg mice and determined the level of IgM production in response to LPS stimulation. As previously described (5), our results show that LPS-stimulated MZ B cells produce much higher levels of IgM compared to wt FM B cells (Figure 7A). In addition, c-myc tg MZp/MZ B cells produced nearly identical levels of IgM as their wt counterparts (Fig 7A). In contrast, c-myc tg FM B cells produced significantly more IgM than wt FM cells, although these levels remained less (approximately 1/3) than those produced by MZp/MZ B cells.

Figure 7. c-myc tg FM B cells exhibit T cell- independent immune responses.

A. Sort purified FM vs MZp/MZ B cells from wt and c-myc tg mice were stimulated with 20µg/ml LPS for 3 days and IgM in the supernatant was measured by ELISA. Data from 3 mice per group are shown. B–C. Wt vs. c-myc tg mice were injected intravenously with TNP-Ficoll and sacrificed 30min later. Splenocytes were isolated and stained with anti-TNP in addition to cell surface markers to detect TNP binding in different B cell subsets. B. Representative histograms of TNP binding with an unmanipulated mouse as control. C. MFI and relative fold change of MFI in TNP binding in each gated B cell subset with cells of an unmanipulated mouse set as 1. Shown is the mean of two animals with SD.

We also determined whether FM B cells derived from wt vs. c-myc tg mice gained the capacity to bind the T-independent type II antigen, TNP-Ficoll, following intravenous in vivo immunization. Consistent with previously published data (7), binding of TNP was significantly higher in MZp/MZ B cells compared to FM B cells; and was equivalent for MZ cells derived from either wt and c-myc tg mice. Notably, c-myc tg FM B cells bound more TNP than wt FM B cells, although still less than MZp/MZ B cells (Fig 7B). Together, these data indicate that over-expression of c-myc within FM B cells results in an increased capacity to participate in T cell-independent immune responses similar to the functional responses of MZ B cells.

DISCUSSION

The current study was designed to address the potential events that limit the capacity of FM B cells to enter cell cycle in response to LPS. Surprisingly, this delay in cell cycle entry is not predominantly due to differential sensitivity of FM vs. MZ B cells to LPS. Indeed, our data indicate that both proximal LPS signaling pathways and downstream LPS driven transcriptional activity are similarly activated in FM and MZ B cells. In contrast, the basal activation status of MZ B cells was significantly enhanced thereby enabling this population to rapidly enter cell cycle after LPS stimulation. Most notably, basal c-myc transcript and protein levels were significantly lower in FM compared to MZ B cells. Together, our findings suggest that, in the majority of FM B cells, LPS stimulation fails to promote a sufficient level of c-myc to permit cell cycle entry. In contrast, MZp/MZ B cells attain this threshold via LPS-driven c-myc transcription in combination with higher basal levels of c-myc. Consistent with this interpretation, provision of higher basal levels of c-myc was sufficient to rescue the proliferative defect in FM B cells.

Several previous reports have demonstrated that FM B cells, compared to MZ B cells, proliferate poorly in response to LPS (5–7). These findings, in association with data showing higher levels of activation markers and reduced LPS-driven IgM production, have led to the interpretation that FM B cells are inherently less responsive to LPS. Consistent with this idea, we and others have also reported that RP105/MD-1, the key TLR4 co-receptor adaptor that confers LPS responsiveness in B cells (24), is expressed at significantly higher levels on MZ compared to FM B cells (14, 25). However, in contrast to this view, our current data indicate that LPS stimulation (even at doses as low as 0.1 µg/ml) leads to a similar fold change in activation markers in FM vs. MZ B cells and that FM B cells differ in relative responsiveness only at very low doses of LPS. Activation of early signaling pathways was also comparable in FM and MZ B cells upon LPS stimulation: the kinetics of IκBα degradation and inducible phosphorylation of the ribosomal protein S6 (as a measurement for activation of the mTOR pathway) were similar in both B cell subsets. In addition, the induction of the TLR target genes AID and BAFF-R also occurred with similar kinetics in both mature populations. Together, these findings indicate that the observed delay in cell cycle entry in FM B cells was unlikely due to a failure to respond to LPS. Notably, previous work also suggests that a similar cycling-specific deficit may also exist in naïve, human, peripheral blood B cells. In contrast to memory B cells, naïve human B cells fail to proliferate in response to the TLR9 ligand, CPG; yet both populations exhibit up-regulation of CD69 and CD86 and an increase in cell size following TLR9 stimulation (26).

Importantly, and as suggested by a recent report (18), our data indicate that the mTOR signaling cascade can be activated independently of proximal PI3K signaling in B cells in response to LPS. Although the fold induction of mTOR activation upon LPS stimulation was similar in FM and MZ cells, MZ B cells exhibited much higher basal PI3K and mTOR activity based upon assessment of relative phosphorylation of AKT and S6, respectively. To test if this pre-activation state was important in promoting LPS-driven cell cycle entry in MZ B cells, we pharmacologically blocked the PI3K vs. the mTOR pathways and assessed relative expression of activation markers as well as cell proliferation. Inhibition of the PI3K pathway had little effect on these events. In contrast, mTOR inhibition significantly reduced proliferation yet had little effect on activation marker expression, indicating that mTOR signaling is essential for LPS-driven cell cycle entry and that basal mTOR signaling in MZ B cells contributes substantially to the ability of this subset to rapidly enter cell cycle entry in response to LPS.

The most striking observation in this study is the role for c-myc levels in controlling FM B cell cycle entry upon LPS stimulation. The proto-oncogene c-myc is a member of the myc transcription factor family (c-, N- and L-myc) and is involved in multiple cellular functions, including cell cycle regulation, proliferation, growth, apoptosis, differentiation and metabolism (reviewed in (27)). c-myc is crucial for normal B cell growth and differentiation and deregulated c-myc expression contributes to development of a range of human malignancies (28, 29). Accordingly, c-myc deficiency results in impaired B cell development at the pre-B cell stage leading to reduced numbers of B cells in both the bone marrow and periphery, and c-myc tg mice exhibit an increase in bone marow B cells and develop pre-B cell leukemias. c-myc is also crucial for proliferation of mature B cells in response to mitogenic stimuli including both BCR and TLR4 stimulation (22, 30) and stimulation of bulk splenic B cells with LPS results in rapid up-regulation of c-myc transcript levels (31), (32).

Grumont et. al. have also previously demonstrated that total c-myc levels are important for controlling B cell cell-cycle entry (22). Further, a threshold level of c-myc is required for cells to enter S phase and previous work has indicated that c-myc controls the decision of cells to divide or not (33, 34). Notably, our analyses show that distinct mature splenic B cell subsets exhibit a major difference in basal c-myc transcript and protein levels. Basal c-myc protein levels were significantly higher in MZ compared to FM B cells, and correlated with mRNA expression as determined by quantitative real-time PCR. While c-myc transcripts were similarly induced in both subsets in response to all doses of LPS, our combined findings suggest that this initial difference in basal c-myc expression is crucial in dictating the cycling response of MZ vs. FM B cells. Consistent with this idea, increased expression of c-myc rescues the cycling deficit in FM B cells and permits a robust FM B cell proliferative response, similar to that of wt MZ B cells in response to LPS.

Interestingly, although the majority of FM B cells failed to cycle at early time points following LPS stimulation, a fraction of sort-purified cells consistently entered cell cycle within 48 hr. Assuming that c-myc up-regulation occurs in a stochastic manner within the overall pool of FM B cells, we would predict that a limited number of cells might attain threshold c-myc levels necessary to enter cell cycle. As it is challenging to directly prove this idea, we sorted proliferating versus non-proliferating FM B cells 3 days after LPS stimulation based on CFSE dilution (CFSEhi vs CFSElow) and determined c-myc transcript expression. Although c-myc was higher in proliferating compared to non-proliferating cells, overall transcript levels were relatively low (data not shown). This is not surprising since highest levels of myc expression occur within hours of LPS stimulation. An alternative explanation for the observed proliferation of a limited fraction of FM B cells is that these cells may have encountered local co-stimulatory signals in vivo, such as CD40 or Notch ligand, thereby leading to higher basal c-myc levels prior to LPS stimulation in vitro.

Notably, although our data document differential c-myc expression in FM vs. MZ B cells, the signal(s) that establishes this basal difference remains to be identified. While the mTOR pathway plays a crucial role in supporting LPS induced proliferation, inhibition of the mTOR pathway does not lead to reduced c-myc expression levels. Thus, while the mTOR pathway promotes cycling it does not appear to directly regulate c-myc levels. A key candidate pathway in this regard is BAFF-R signaling. BAFF is the most important B cell survival factor in the periphery and BAFF signals are crucial for MZ B cell development (35). BAFF-R dependent non-canonical NFκB signals strongly promote the mTOR cascade (36), (37); and it is possible that in parallel BAFF-triggered canonical NFκB signals may directly modulate c-myc expression. MZ B cells express significantly higher levels of BAFF-R compared with FM cells (15); thus, increased canonical NFκB signals in this subset may be sufficient to explain their higher basal levels of c-myc expression. Finally, it is important to point out that increased c-myc expression alone, is not sufficient to drive FM B cells into cycle: c-myc tg B cells (MZ or FM B cells) do not spontaneously proliferate; and the proliferative response of c-myc tg FM B cells remains LPS dose dependent. Additional studies will be required to define the signals that synergize to promote cycling including, in particular, the specific components of the mTOR cascade necessary for these events.

In summary, our findings contribute to a better understanding of the regulation of TLR signals in mature B cell subsets. While MZ B cells have been shown to function primarily as innate-like immune cells, FM B cells largely generate an adaptive immune response that can be amplified by TLR co-stimulation. In FM B cells, the tight control of TLR4-dependent proliferative response likely functions to limit nonspecific amplification of self-reactive cells and thereby help prevent the development of autoimmunity. Consistent with this idea, and the concept that clonal expansion is important prior to antibody production, our data show that over-expression of c-myc in FM B cells also results in an increased facility to produce IgM after stimulation with LPS in vitro, and in a greater capacity for T-independent, type II antigen binding in vivo. The importance of TLR signals (in the absence of exogenously delivered TLR ligands) for the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases has recently been shown by crossing BAFF tg mice with MyD88 deficient animals. Under these conditions, the development of the lupus-like autoimmunity characteristic of BAFF tg mice is largely eliminated, thereby highlighting the importance for B cell intrinsic TLR signals in these events (38). Taken in concert with other reports showing the role of B cell autonomous TLR signaling in autoimmunity (reviewed in (39)), our findings suggest that tight regulation of TLR signaling in FM B cells may be critical for B cell tolerance. Notably, FM B cells proliferate robustly to LPS in association with either BCR or CD40 co-stimulation (14). These combined observations suggest that B cells that receive an antigen-specific signal may be synergistically amplified via TLR signals. Thus, approaches aimed at limiting TLR signals in activated mature FM B cells may provide an important therapeutic avenue for use in patients with a range of autoimmune diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Brian Iritani (University of Washington) for providing c-myc transgenic mice, Jaya Sahni (University of Washington) for technical advice, Socheath Khim (Seattle Children’s Research Institute) for assistance with animal husbandry and all member of the Rawlings lab for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Support for this work has included the Elizabeth Campbell Endowment (AMB), National Cancer Institute immunology training grant (ADB), Cancer Research Institute immunology training grant (SFA) and NIH grants HD37091, CA81140, and HL075453 (to DJR).

REFERENCES

- 1.Martin F, Kearney JF. B-cell subsets and the mature preimmune repertoire. Marginal zone and B1 B cells as part of a "natural immune memory". Immunol Rev. 2000;175:70–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saito T, Chiba S, Ichikawa M, Kunisato A, Asai T, Shimizu K, Yamaguchi T, Yamamoto G, Seo S, Kumano K, Nakagami-Yamaguchi E, Hamada Y, Aizawa S, Hirai H. Notch2 is preferentially expressed in mature B cells and indispensable for marginal zone B lineage development. Immunity. 2003;18:675–685. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kin NW, Crawford DM, Liu J, Behrens TW, Kearney JF. DNA Microarray Gene Expression Profile of Marginal Zone versus Follicular B Cells and Idiotype Positive Marginal Zone B Cells before and after Immunization with Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Immunol. 2008;180:6663–6674. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bendelac A, Bonneville M, Kearney JF. Autoreactivity by design: innate B and T lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:177–186. doi: 10.1038/35105052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliver AM, Martin F, Gartland GL, Carter RH, Kearney JF. Marginal zone B cells exhibit unique activation, proliferative and immunoglobulin secretory responses. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2366–2374. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliver AM, Martin F, Kearney JF. IgMhighCD21high lymphocytes enriched in the splenic marginal zone generate effector cells more rapidly than the bulk of follicular B cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:7198–7207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srivastava B, Quinn WJ, 3rd, Hazard K, Erikson J, Allman D. Characterization of marginal zone B cell precursors. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1225–1234. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leadbetter EA, Rifkin IR, Hohlbaum AM, Beaudette BC, Shlomchik MJ, Marshak-Rothstein A. Chromatin-IgG complexes activate B cells by dual engagement of IgM and Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2002;416:603–607. doi: 10.1038/416603a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viglianti GA, Lau CM, Hanley TM, Miko BA, Shlomchik MJ, Marshak-Rothstein A. Activation of autoreactive B cells by CpG dsDNA. Immunity. 2003;19:837–847. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00323-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams JM, Harris AW, Pinkert CA, Corcoran LM, Alexander WS, Cory S, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL. The c-myc oncogene driven by immunoglobulin enhancers induces lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice. Nature. 1985;318:533–538. doi: 10.1038/318533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity. 1999;11:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoebe K, Du X, Georgel P, Janssen E, Tabeta K, Kim SO, Goode J, Lin P, Mann N, Mudd S, Crozat K, Sovath S, Han J, Beutler B. Identification of Lps2 as a key transducer of MyD88-independent TIR signalling. Nature. 2003;424:743–748. doi: 10.1038/nature01889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer-Bahlburg A, Khim S, Rawlings DJ. B cell intrinsic TLR signals amplify but are not required for humoral immunity. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3095–3101. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer-Bahlburg A, Andrews SF, Yu KO, Porcelli SA, Rawlings DJ. Characterization of a late transitional B cell population highly sensitive to BAFF-mediated homeostatic proliferation. J Exp Med. 2008;205:155–168. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sen R. Control of B lymphocyte apoptosis by the transcription factor NF-kappaB. Immunity. 2006;25:871–883. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siebenlist U, Brown K, Claudio E. Control of lymphocyte development by nuclear factor-kappaB. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:435–445. doi: 10.1038/nri1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donahue AC, Fruman DA. Distinct signaling mechanisms activate the target of rapamycin in response to different B-cell stimuli. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2923–2936. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Craxton A, Hendricks DW, Merino MC, Montes CL, Clark EA, Gruppi A. BAFF and LPS cooperate to induce B cells to become susceptible to CD95/Fas-mediated cell death. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:990–1000. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grumont RJ, Rourke IJ, Gerondakis S. Rel-dependent induction of A1 transcription is required to protect B cells from antigen receptor ligation-induced apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:400–411. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee H, Arsura M, Wu M, Duyao M, Buckler AJ, Sonenshein GE. Role of Rel-related factors in control of c-myc gene transcription in receptor-mediated apoptosis of the murine B cell WEHI 231 line. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1169–1177. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grumont RJ, Strasser A, Gerondakis S. B cell growth is controlled by phosphatidylinosotol 3-kinase-dependent induction of Rel/NF-kappaB regulated c-myc transcription. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1283–1294. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00779-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adhikary S, Eilers M. Transcriptional regulation and transformation by Myc proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:635–645. doi: 10.1038/nrm1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogata H, Su I, Miyake K, Nagai Y, Akashi S, Mecklenbrauker I, Rajewsky K, Kimoto M, Tarakhovsky A. The toll-like receptor protein RP105 regulates lipopolysaccharide signaling in B cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:23–29. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gunn KE, Brewer JW. Evidence that marginal zone B cells possess an enhanced secretory apparatus and exhibit superior secretory activity. J Immunol. 2006;177:3791–3798. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernasconi NL, Traggiai E, Lanzavecchia A. Maintenance of serological memory by polyclonal activation of human memory B cells. Science. 2002;298:2199–2202. doi: 10.1126/science.1076071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Junttila MR, Westermarck J. Mechanisms of MYC stabilization in human malignancies. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:592–596. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.5.5492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habib T, Park H, Tsang M, de Alboran IM, Nicks A, Wilson L, Knoepfler PS, Andrews S, Rawlings DJ, Eisenman RN, Iritani BM. Myc stimulates B lymphocyte differentiation and amplifies calcium signaling. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:717–731. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iritani BM, Eisenman RN. c-Myc enhances protein synthesis and cell size during B lymphocyte development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13180–13185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerondakis S, Grumont RJ, Banerjee A. Regulating B-cell activation and survival in response to TLR signals. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:471–475. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carman JA, Wechsler-Reya RJ, Monroe JG. Immature stage B cells enter but do not progress beyond the early G1 phase of the cell cycle in response to antigen receptor signaling. J Immunol. 1996;156:4562–4569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong KK, Hardin JD, Boast S, Cooper CL, Merrell KT, Doyle TG, Goff SP, Calame KL. A role for c-Abl in c-myc regulation. Oncogene. 1995;10:705–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conlon I, Raff M. Size control in animal development. Cell. 1999;96:235–244. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80563-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trumpp A, Refaeli Y, Oskarsson T, Gasser S, Murphy M, Martin GR, Bishop JM. c-Myc regulates mammalian body size by controlling cell number but not cell size. Nature. 2001;414:768–773. doi: 10.1038/414768a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cancro MP. The BLyS family of ligands and receptors: an archetype for niche-specific homeostatic regulation. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:237–249. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woodland RT, Schmidt MR, Thompson CB. BLyS and B cell homeostasis. Semin Immunol. 2006;18:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woodland RT, Fox CJ, Schmidt MR, Hammerman PS, Opferman JT, Korsmeyer SJ, Hilbert DM, Thompson CB. Multiple signaling pathways promote B lymphocyte stimulator dependent B-cell growth and survival. Blood. 2008;111:750–760. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-077222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Groom JR, Fletcher CA, Walters SN, Grey ST, Watt SV, Sweet MJ, Smyth MJ, Mackay CR, Mackay F. BAFF and MyD88 signals promote a lupuslike disease independent of T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1959–1971. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer-Bahlburg A, Rawlings DJ. B cell autonomous TLR signaling and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;7:313–316. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2007.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]