Abstract

Background

Motivation is a critical factor in supporting sustained exercise, which in turn is associated with important health outcomes. Accordingly, research on exercise motivation from the perspective of self-determination theory (SDT) has grown considerably in recent years. Previous reviews have been mostly narrative and theoretical. Aiming at a more comprehensive review of empirical data, this article examines the empirical literature on the relations between key SDT-based constructs and exercise and physical activity behavioral outcomes.

Methods

This systematic review includes 66 empirical studies published up to June 2011, including experimental, cross-sectional, and prospective studies that have measured exercise causality orientations, autonomy/need support and need satisfaction, exercise motives (or goal contents), and exercise self-regulations and motivation. We also studied SDT-based interventions aimed at increasing exercise behavior. In all studies, actual or self-reported exercise/physical activity, including attendance, was analyzed as the dependent variable. Findings are summarized based on quantitative analysis of the evidence.

Results

The results show consistent support for a positive relation between more autonomous forms of motivation and exercise, with a trend towards identified regulation predicting initial/short-term adoption more strongly than intrinsic motivation, and intrinsic motivation being more predictive of long-term exercise adherence. The literature is also consistent in that competence satisfaction and more intrinsic motives positively predict exercise participation across a range of samples and settings. Mixed evidence was found concerning the role of other types of motives (e.g., health/fitness and body-related), and also the specific nature and consequences of introjected regulation. The majority of studies have employed descriptive (i.e., non-experimental) designs but similar results are found across cross-sectional, prospective, and experimental designs.

Conclusion

Overall, the literature provides good evidence for the value of SDT in understanding exercise behavior, demonstrating the importance of autonomous (identified and intrinsic) regulations in fostering physical activity. Nevertheless, there remain some inconsistencies and mixed evidence with regard to the relations between specific SDT constructs and exercise. Particular limitations concerning the different associations explored in the literature are discussed in the context of refining the application of SDT to exercise and physical activity promotion, and integrating these with avenues for future research.

Introduction

Physical activity and exercise, when undertaken regularly, are highly beneficial for health, and for physical and psychological well-being [e.g., [1]. Yet, only a minority of adults in modern societies reports engaging in physical exercise at a level compatible with most public health guidelines [2]. For instance, 2009 data indicate that, on a typical week, 60% of adults in Europe engaged in no physical exercise or sports [3]. In the US, less than 50% of adults are considered regularly physically active [4] while in Canada new accelerometer data shows that only 15% of adults meet national physical activity recommendations [5]. Such findings suggest that many people lack sufficient motivation to participate in the 150 minutes of moderately intense exercise or physical activitya per week recommended [6]. Indeed, approximately 40% of Europeans agree with the statement: “Being physically active does not really interest me – I would rather do other things with my spare time” [3].

Lack of motivation can broadly be explained by two orders of factors. First, as highlighted in the previous statistic, people may not be sufficiently interested in exercise, or value its outcomes enough to make it a priority in their lives [7]. Many individuals experience competing demands on their time from educational, career, and family obligations, possibly at the expense of time and resources that could be invested in exercising regularly. Second, some people may not feel sufficiently competent at physical activities, feeling either not physically fit enough or skilled enough to exercise, or they may have health limitations that present a barrier to activity [8]. Whether it be low interest or low perceived competence, the physical activity participation data indicate that many people are either unmotivated (or amotivated), having no intention to be more physically active, or are insufficiently motivated in the face of other interests or demands on their time.

In addition to those who are unmotivated, another source of short-lived persistence in exercise behaviors comes from people who do express personal motivation to exercise regularly, yet initiate exercise behaviors with little follow through. Specifically, a significant percentage of people may exercise because of controlled motivations, where participation in activities like going to the gym or running regularly is based on a feeling of “having to” rather than truly “wanting to” participate [7]. Controlled forms of motivation, which by definition are not autonomous (i.e., they lack volition), are predominant when the activity is perceived primarily as a means to an end and are typically associated with motives or goals such as improving appearance or receiving a tangible reward [9]. One hypothesis then is that the stability of one’s motivation is at least partially dependent on some of its qualitative features, particularly the degree of perceived autonomy or of an internal perceived locus of causality[10]. That is, the level of reflective self-endorsement and willingness associated with a behavior or class of behaviors should be associated with greater persistence. An utilitarian approach to exercise (and to exercise motivation), such as might be prevalent in fitness clubs or other settings where exercise is externally prescribed, could thus be partially responsible for the high dropout rate observed in exercise studies [e.g., [11]. In fact, the pervasiveness of social and medical pressures toward weight loss, combined with externally prescriptive methods may be ill-suited to promote sustained increases in population physical activity levels.

In sum, large numbers of individuals are either unmotivated or not sufficiently motivated to be physically active, or are motivated by types of externally-driven motivation that may not lead to sustained activity. This highlights the need to look more closely at goals and self-regulatory features associated with regular participation in exercise and physical activity. Self-determination theory (SDT) is uniquely placed among theories of human motivation to examine the differential effects of qualitatively different types of motivation that can underlie behavior [12]. Originating from a humanistic perspective, hence fundamentally centered on the fulfillment of needs, self-actualization, and the realization of human potential, SDT is a comprehensive and evolving macro-theory of human personality and motivated behavior [12]. In what follows we will briefly describe key concepts formulated within SDT (and tested in SDT empirical studies) that are more relevant to physical activity and exercise, all of which will be implicated in our empirical review.

First, SDT distinguishes between intrinsic and extrinsic types of motivation regulating one’s behavior. Intrinsic motivation is defined as doing an activity because of its inherent satisfactions. When intrinsically motivated the person experiences feelings of enjoyment, the exercise of their skills, personal accomplishment, and excitement [13]. To different degrees, recreational sport and exercise can certainly be performed for the associated enjoyment or for the challenge of participating in an activity. In contrast to intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation refers to doing an activity for instrumental reasons, or to obtain some outcome separable from the activity per se. For example, when a person engages in an activity to gain a tangible or social reward or to avoid disapproval, they are extrinsically motivated. SDT, however, conceptualizes qualitatively different types of extrinsic motivation, that themselves differ in terms of their relative autonomy. Some extrinsic motives are relatively heteronomous, representing what in SDT are described as controlled forms of motivation. For example, externally regulated behaviors are those performed to comply with externally administered reward and punishment contingencies. Also controlled are extrinsic motivations based on introjected regulation, where behavior is driven by self-approval. Controlled forms of extrinsic motivation are expected within SDT to sometimes regulate (or motivate) short-term behavior, but not to sustain maintenance over time [14]. Yet not all extrinsic motives are controlled. When a person does an activity not because it is inherently fun or satisfying (intrinsic motivation), but rather because it is of personal value and utility, it can represent a more autonomous form of behavioral regulation. Specifically in SDT, identified and integrated forms of behavioral regulation are defined as those in which one’s actions are self-endorsed because they are personally valued. Examples include exercising because one values its outcomes and desires to maintain good health [7]. Thus, in SDT, these different forms of motivation are conceptualized as lying along a continuum from non-autonomous to completely autonomous forms of behavioral regulation.

Third, SDT introduces the concept of basic psychological needs as central to understanding both the satisfactions and supports necessary for high quality, autonomous forms of motivation. Specifically SDT argues that there are basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, all of which are conceived as essential and universal nutriments to psychological health and the development of internal motivation. Satisfaction of these basic needs results in increased feelings of vitality and well-being [15]. Like any other activity, engaging in sports and exercise can be more or less conducive to having one’s psychological needs realized [16]. For example, experiences of competence vary upon success or failure at challenging physical tasks or as a function of feedback from, for example, a fitness professional. Perceptions of personal connection (relatedness) with others (e.g., fellow members of a fitness class or weight loss program) can vary greatly as a function of the interpersonal environment. Feelings of autonomy (versus feeling controlled) differ as a function of communication styles in exercise settings. According to SDT, in fact, need fulfillment in any context is closely associated with the characteristics of that social milieu, that is, whether important others support the needs for autonomy (e.g., take the perspective of the client/patient, support their choices, minimize pressure), relatedness (e.g., create an empathetic and positive environment, show unconditional regard), and competence (e.g., limit negative feedback, provide optimally challenging tasks). The concept of need support is thus thought to largely explain individual differences in the development and enactment of motivation across the lifespan [12]. Consequently, the design of health behavior change interventions that enhance satisfaction of participants’ basic needs is a matter of much interest in SDT studies, including in the area of exercise and physical activity [17,18].

More recently, goal contents have also been explored from an SDT perspective in relation to a range of behaviors, including exercise [e.g., [19,20]. It should be noted that most authors have referred to goal contents in exercise contexts as motives, or more specifically participation motives [e.g., [64,79]. Operationally both terms are identical and we will use them interchangeably herein. Whereas intrinsic motivation and the various forms of extrinsic motivation represent the regulatory processes underlying a behavior, motives or goal contents are the outcomes that individuals are pursuing by engaging in the behavior [12]. Goal contents are differentiated according to the extent to which their pursuit is likely to satisfy basic psychological needs. Specifically, SDT distinguishes intrinsic goals (e.g., seeking affiliation, personal growth, or health) as those thought to be more closely related to the fulfillment of basic psychological needs, from extrinsic goals (e.g., seeking power and influence, wealth, or social recognition) that are thought to be associated with “substitute needs” which are neither universal nor truly essential to well-being and personal development. Factor analytic studies have borne out this theoretical distinction, and a number of studies have shown the predicted differential consequences of intrinsic versus extrinsic goal importance [21,22]. Within the domain of exercise and physical activity, extrinsic goals (e.g., when exercise is performed primarily to improve appearance) or intrinsic goals (e.g., to challenge oneself or to improve/preserve health and well-being) can clearly be distinguished. It should be noted that different goals or motives towards a given activity often naturally co-exist in the same person, some being more intrinsic, some less. Similar to what occurs with motivational regulations (which can have more or less autonomous elements, see more below), it is the relative preponderance of certain types of motives versus others which is thought to determine more or less desirable outcomes [e.g., [19,20].

Finally, SDT also proposes that people have dispositional tendencies, named causality orientations[14] which describe the way they preferentially orient towards their environments, resulting in characteristic motivational and behavioral patterns. Although some people may be more inclined to seek out and follow their internal indicators of preference in choosing their course of action, others may more naturally tend to align with external directives and norms, while still others may reveal to be generally amotivated, more passive, and unresponsive to either internal or external events that could energize their actions [12]. Although this topic has not been explored at length in previous research, these orientations can manifest themselves (and be measured) in exercise and physical activity contexts and the Exercise Causality Orientation Scale has been developed to measure individual differences in orientations around exercise [9].

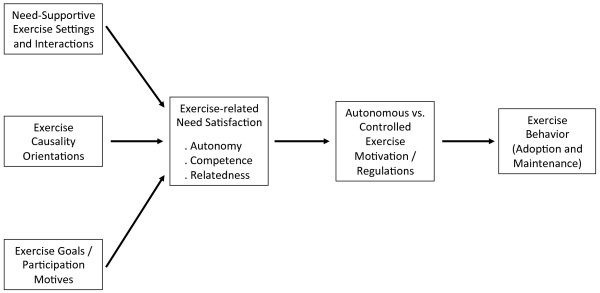

Previous review papers of the topic of SDT and physical activity have primarily focused on describing the rationale for the application of this particular theoretical framework to physical activity behaviors, reviewing illustrative studies [7,23,24]. Meanwhile, the SDT-related exercise empirical research base has grown considerably in recent years, warranting a more comprehensive and systematic review of empirical data. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of empirical studies provide the highest level of evidence for the appraisal and synthesis of findings from scientific studies. Accordingly, the present review includes 66 empirical studies published up to June 2011 that assessed relations between SDT-based constructs or interventions and exercise outcomes. We included experimental and cross-sectional studies that have measured exercise causality orientations, autonomy/need support and need satisfaction, exercise motives or goals, and exercise self-regulations and motivation. We also studied SDT-based interventions as predictors of exercise behavioral outcomes. Figure 1 depicts a general model of SDT and exercise, where its major constructs and theoretical links are highlighted.

Figure 1.

General SDT process model for exercise behavior. Adapted from the general health process model (Ref Ryan et al., Europ Health Psych, 2009), this graph includes the 5 groups of variables analyzed in this review as exercise predictors and their expected relationships (in a simplified version). Although this review only covers direct relationships between each class of variables (e.g., need satisfaction in exercise) and exercise behaviors, since few articles have simultaneously tested various steps of this model, the SDT model for exercise assumes that a sizable share of variance of exercise associated with SDT variables may be explained via indirect or mediating mechanisms, as depicted. See Discussion for more details.

Methods

Data sources and procedure

This review is limited to articles written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals covering adult samples. Research on autonomy and exercise in adolescents and children (typically based in school and physical education) was excluded, as well as studies with competitive athletic samples. Both are specific settings and were considered distinct from leisure-time or health-related exercise participation in adults, the focus of this review. The review includes both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, investigating clinical and/or general population samples, and using diverse quantitative methodological approaches. A systematic literature search of studies published between 1960 and June 2011 was undertaken on the computerized psychological and sport databases PsycINFO and SportDiscus. The following strategy was used: TX (autonomous motivation OR autonomous regulation OR intrinsic motivation OR controlled regulation OR autonomy OR self-determination OR treatment regulations OR goals OR motives OR basic needs OR autonomy-supportive climate) AND TX (physical activity OR exercise OR exercise behavior OR leisure-time physical activity) Limiters were: Scholarly (peer-reviewed) journals; English Language; Adulthood (> 18 yr); Specific subjects: exercise OR motivation OR self-determination. This search yielded 660 articles. Abstracts were read and, of those, all potentially relevant full manuscripts were retrieved (n = 73). At this stage, studies were excluded which did not include either SDT variables or physical activity variables (accounting for most of the excluded studies), that used non-adult samples, and that reported achievement/performance outcomes related to PE classes. Next, reference lists of retrieved articles, previous review articles on the topic, and books were also reviewed, and manual searches were conducted in the databases and journals for authors who regularly publish in this area. This search yielded 11 additional manuscripts, totaling 84 potentially relevant manuscripts. Next, manuscripts were read and the following inclusion criteria used to select the final set of manuscripts: inclusion of non-athletic samples; outcomes included exercise/physical activity behaviors; reported direct associations between self-determination variables and physical activity outcomes. A total of 66 studies fulfilled all inclusion criteria and thus were included in this review. Of these, ten were experimental, eleven prospective, forty-two cross-sectional, and three used mixed designs.

Studies were initially coded with a bibliography number, but independent samples (K) were considered as the unit of analysis in the current review since a few studies used the same sample while other studies reported analyses on multiple samples. Data tables (Table 1) were constructed and encompassed sample characteristics of study populations, motivational predictors of exercise behavior, instruments of assessment, exercise-related outcomes, research designs, and statistical methods used to test the associations.

Table 1.

Description of reviewed studies

|

Reference |

Design |

Sample |

Measures |

Significant Predictors |

Outcomes |

Analysis/Observations |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (%F) | Features | Location | |||||||

|

I. Exercise self-regulations and related measures | |||||||||

| ThØgersen-Ntoumani & Ntoumanis, 2006 [52] |

Cross-sectional |

375 (51) |

Exercisers (Mean 38.7 yr) |

UK |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ) + amotivation (AMS) |

MV: IM (+) a, ID (+) a,b, INTR (+) a; EXT (−) a,b, AMOT (−) a |

Exercise stages of change a; Exercise relapses (fewer) b |

Multivariate logistic regressions, adjusting for sex and age; Manovas |

|

| Rose et al., 2005 [56] |

Cross-sectional |

184 (55) |

Healthy adults (17–60 yr) |

UK |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ) |

MV: IM (+) a, ID (+) , INTR (+) EXT (−) |

Exercise stages of change |

Discriminant function analysis (IM was redundant); Manovas a |

|

| Ingledew et al., 2009 [79] |

Cross-sectional |

251 (52) |

University Students (Mean 19.5 yr) |

UK |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2) |

MV: IM (+),ID (+),INTR (n.s) EXT (n.s) |

Self-reported exercise (measure analogous to LTEQ) |

Partial Least Squares Analysis (PLS); Mediation analysis |

|

| Edmunds et al., 2006 [44] |

Cross-sectional |

369 (52) |

Healthy individuals (Mean 31.9 yr) |

UK |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ) |

MV: IM (n.s.), ID (+), INTR (+), EXT (−) |

Self-reported exercise (total and strenuous PA; LTEQ) |

Multiple regressions; Mediation analysis. No associations with mild/moderately intense PA. |

|

|

BIV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (+), EXT (n.s.) | |||||||||

| Wilson et al., 2006 [85] |

Cross-sectional |

139 (64) |

Undergraduate students (Mean 19.5 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise extrinsic self-regulations (BREQ) and Integrated Regulation scale (INTEG) |

MV: INTEG (+), ID (+), INTR (+), EXT (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations; Multiple regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: INTEG (+), ID (n.s.), INTR (n.s.), EXT (n.s.) | |||||||||

| McDonough et al., 2007 [50] |

Cross-sectional |

558 (72) |

|

|

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ) |

MV: RAI (+) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations; SEM; Mediation analysis. Only RAI was tested in multivariate analysis. |

|

|

BIV: RAI (+), IM (n.s.), ID (+), INTR (n.s.), EXT (n.s.) | |||||||||

| Daley & Duda, 2006 [55] |

Cross-sectional |

409 (61) |

Undergraduate students (19.9 yr) |

UK |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2) |

MV: IM (+), ID (++), INTR (+); EXT (− M); AMOT (− F) |

Exercise stages of change; Physical activity status (from inactive to active) |

Discriminant function analysis |

|

| Wilson et al., 2004 [45] |

Cross-sectional |

276 (64) |

Undergraduate students (20.5 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2) |

MV: IM (n.s.); ID (+), INTR (+ F; - M), EXT (n.s.), AMOT (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations; Multiple regressions analysis |

|

|

BIV: IM (+); ID (+), INTR (+ F), EXT (n.s.), AMOT (n.s.) | |||||||||

| Markland, 2009 [9] |

Cross-sectional |

102 F |

Healthy individuals (Mean 29.2 yr) |

UK |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2) |

MV: IM (+), ID (+), AMOT (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations; Multiple regression/mediation (Preacher & Hayes): INTR and EXT not analyzed. |

|

|

BIV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (+), EXT (n.s.), AMOT (−) | |||||||||

| Ingledew & Markland, 2008 [46] |

Cross-sectional |

252 (48) |

Office workers (Mean 40 yr) |

UK |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2) |

MV: IM (n.s.), ID (+), INTR (n.s.), EXT (−) |

Self-reported exercise (measure analogous to LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations; SEM |

|

|

BIV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (n.s.), EXT (−) | |||||||||

| Peddle et al., 2008 [43] |

Cross-sectional |

413 (46) |

Colorectal cancer survivors (Mean 60 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2) |

MV: IM (n.s.), ID (+), INTR (+), EXT (n.s.), AMOT (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations; Path analysis |

|

|

BIV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (+), EXT (n.s.), AMOT (−) | |||||||||

| Landry & Solmon, 2004 [86] |

Cross-sectional |

105 F |

African-American (Mean 56 yr) |

USA |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ) |

MV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (−), EXT (n.s.) |

Exercise stages of change; exercise categories |

Anovas; Discriminant function analysis |

|

| |

BIV: RAI (+); IM (+), ID (+), INTR (n.s.), EXT (n.s.) |

||||||||

| Milne et al., 2008 [87] |

Cross-sectional |

558 F |

Breast cancer survivors (Mean 59 yr) |

Australia |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2) |

MV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (n.s.), EXT (n.s.), AMOT (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ); exercise categories (meeting vs. not meeting guidelines) |

Anovas; Hierarchical regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (n.s.), EXT (−), AMOT (−) | |||||||||

| Mullan & Markland, 1997 [57] |

Cross-sectional |

314 (49.7) |

Healthy individuals (Mean 35–40 yr) |

UK |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ) |

MV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (n.s.), EXT (n.s.) |

Exercise stages of change |

Anova (RAI was analyzed); Discriminant function analysis; |

|

|

BIV: RAI (+) | |||||||||

| Lewis & Sutton, 2011 [48] |

Cross-sectional |

100 (50) |

95% undergraduates, members of a university gym; age not specified |

UK |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2) |

MV: IM (+); ID (n.s.), INTR (n.s.), EXT (−), AMOT (n.s.) |

Exercise frequency |

Bivariate correlations; Multiple regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: IM (+); ID (+), INTR (+), EXT (−), AMOT (−) | |||||||||

| Markland & Tobin, 2010 [88] |

Cross-sectional |

133 F |

Exercise referral scheme clients (Mean 54.5 yr) |

UK |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2) |

BIV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (n.s.), EXT (n.s.), AMOT (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| Wilson et al., 2002 [49] |

Cross-sectional |

500 (81) |

Aerobic exercisers (Mean 34 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ) |

BIV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (+), EXT (−) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations. Differences between PA intensities. |

|

| Sebire et al., 2009 [19] |

Cross-sectional |

410 (71) |

Exercisers (Mean 41.4 yr) |

UK |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ) |

MV: RAI (+) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations; Hierarchical regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: RAI (+) | |||||||||

| Brickell & Chatzisarantis, 2007 [42] |

Cross-sectional |

252 (61) |

College students (Mean 23.2 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ) |

MV: IM (n.s.), ID (+), INTR (n.s.), EXT (n.s) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Multiple regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (+), EXT (n.s) | |||||||||

| Edmunds et al., 2006 [51] |

Cross-sectional |

339 (53) |

Symptomatic vs asymptomatic for exercise dependence (Mean 32.1 yr) |

UK |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ) and Integrated Regulation scale (INTEG) |

MV: Symptomatic: INTR (+ tendency); Asymptomatic: ID (+). Remaining variables not significant. |

Self-reported exercise (total and strenuous PA; LTEQ) |

Multiple regressions. No associations with moderately intense PA. |

|

| Moreno et al., 2007 [89] |

Cross-sectional |

561 (53) |

Healthy adults (Mean 31.8 yr) |

Spain |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2) |

MV: IM (n.s.), ID (−), INTR (n.s.), EXT (−), AMOT (−) |

Exercise duration (0-45 min vs. 45-60 min vs. > 60 min) |

Manovas |

|

| Hall et al., 2010 [90] |

Cross-sectional |

470 (54) |

Adults (Mean 44.9 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2); Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

BIV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (+), EXT (n.s.), AMOT (−) |

Exercise status (active vs. inactive) |

Anovas |

|

| Standage et al., 2008 [91] |

Cross-sectional |

52 (50) |

University students (Mean 22 yr) |

UK |

Exercise self-regulations; Autonomous and controlled motivations (BREQ) |

MV: AutMot (+), CtMot (n.s.) BIV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (n.s.), EXT (n.s), AutMot (+), CtMot (n.s.) |

Accelerometry |

Bivariate correlations; Sequential regression analysis |

|

| Duncan et al., 2010 [41] |

Cross-sectional |

1079 (57) |

Regular exercisers (Mean 24.2 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2) + Integrated reg. scale |

MV: IM (n.s.), INTEG (+), ID (+)*, INTR (n.s.), EXT (n.s), AMOT (n.s) |

* PA frequency; PA intensity; PA duration (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations; Multiple regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: IM (+), INTEG (+), ID (+), INTR (+), EXT (− F)*, AMOT (−) | |||||||||

| Sorensen et al. 2006 [54] |

cross-sectional |

109 (59) |

Psychiatric patients (Mean age group 31–49 yr) |

Norway |

Exercise regulations (based on BREQ) |

MV: IM (+), ID (n.s.), INTR (n.s.), EXT (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise level |

Bivariate correlations; Logistic regressions |

|

|

BIV: IM (+), ID (n.s.), INTR (n.s.), EXT (−) | |||||||||

| Puente & Anshel, 2010 [77] |

Cross-sectional |

238 (57) |

College students (Mean 20.4 yr) |

USA |

Exercise self-regulations (SRQ-E) |

MV: RAI (+) |

Exercise frequency |

Bivariate correlations; SEM |

|

|

BIV: RAI (+) | |||||||||

| Halvary et al., 2009 [76] |

Cross-sectional |

190 (44) |

Healthy adults (Mean 21.8 yr) |

Norway |

Autonomous motivation (SRQ) |

MV: AutMot (+) |

Exercise frequency and duration |

Bivariate correlations; SEM; Mediation analysis |

|

|

BIV: AutMot (+) | |||||||||

| Wilson et al., 2006 [29] |

Cross-sectional |

220; 220 (56) |

Cancer survivors (Mean 60–64 yr) vs non-cancer (Mean 50 yr) |

Canada |

Autonomous and controlled motivation (TSRQ-PA) |

MV: AutMot (+), CtMot (−) in both samples |

Self-reported exercise (min/wk of MVPA) |

Bivariate correlations; Multiple regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: AutMot (+), CtMot (n.s.) in both samples | |||||||||

| Hurkmans et al., 2010 [92] |

Cross-sectional |

271 (66) |

Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (Mean 62 yr) |

Netherlands |

Exercise self-regulations (TSRQ-PA). Adated RAI. |

MV: RAI (+) |

Self-reported exercise (SQUASH) |

Bivariate correlations; Multiple regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: RAI (+) | |||||||||

| Lutz et al., 2008 [93] |

Cross-sectional |

535 (60) |

University students (Mean 20 yr) |

USA |

Exercise self-regulations (EMS). Adapted RAI. |

MV: RAI (+) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlation; Preacher & Hayes mediation analysis |

|

|

BIV: RAI (+) | |||||||||

| Wininger, 2007 [28] |

Cross-sectional |

143; 58 (76) |

Undergraduates (Mean 21–22 yr) |

USA |

Exercise self-regulations (EMS) |

MV *: IM (+), INTEG (+), ID (+), INTR (+), EXT (n.s.), AMOT (−) |

* Exercise stages of change; ** Distance walked on treadmill |

Bivariate correlations; Manovas |

|

|

BIV **: IM experience sensations (+), INTEG (n.s.), ID (n.s.), INTR (n.s.), EXT (n.s.), AMOT (−) | |||||||||

| Craike, M., 2008 [47] |

Cross-sectional |

248 (53) |

Healthy adults (Mean 48 yr) |

Australia |

Exercise self-regulations (based on BREQ and EMS) |

MV: IM (+), ID (n.s.), INTR (n.s.), EXT (−) |

Self-reported LTPA |

SEM |

|

| Tsorbatzoudis et al., 2006 [94] |

Cross-sectional |

257 (55) |

Healthy adults (Mean 31 yr) |

Greece |

Exercise self-regulations (SMS) |

MV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (+), EXT (−), AMOT (−) |

Exercise frequency (from the least to the most frequent) |

Multivariate analysis of variance; multiple regressions |

|

| Chatzisarantis & Biddle, 1998 [95] |

Cross-sectional |

102 (50) |

University employees (Mean 40 yr) |

UK |

Behavioral regulations for PA (SMS adaptation) |

MV: Autonomous group (vs controlled) based on RAI scores (+) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

SEM |

|

| Matsumoto & Takenaka, 2004 [96] |

Cross-sectional |

486 (53) |

Healthy individuals (Mean 45 yr) |

Japan |

Exercise self-regulations (SDMS); profiles of self-determination |

BIV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (+), EXT (n.s.) AMOT (−); Self-determined profile (+) |

Exercise stages of change |

Bivariate correlations and cluster analysis |

|

| McNeill et al., 2006 [97] |

Cross-sectional |

910 (80) |

Healthy individuals (Mean 33 yr) |

USA |

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations (MPA) |

MV: Intrinsic motivation (+); Extrinsic motivation for social pressure |

Self-reported exercise (minutes of walking, and MVPA) |

SEM. Indirectly through self-efficacy. |

|

| Russell & Bray, 2009 [98] |

Cross-sectional and prospective (6 + 6wk) |

68 (13) |

Cardiac rehabilitation outpatients (Mean 64.9 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2) |

MV: RAI (+) |

Self-reported exercise (7Day-PAR) |

Bivariate correlations; Multiple regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: RAI (+) | |||||||||

| Russell & Bray, 2010 [99] |

Cross-sectional and Observational (14wk) |

53 M |

Exercise cardiac rehabilitation patients (Mean 62.8 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (SRQ-E) |

MV: AutMot (+) |

Exercise frequency; duration (+); volume (+) – 7Day-PAR |

Bivariate correlations; Hierarchical regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: AutMot (+), CtMot (n.s.) | |||||||||

| Fortier et al., 2009 [100] |

Prospective (6mo) |

149 F |

Healthy adults (Mean 51.8 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (TSRQ-adapted) |

MV: AutMot (n.s.) |

Duration, Frequency, and Energy Expenditure (CHAMPS) |

Bivariate correlations; Mediation/regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: AutMot (n.s.), CtMot (n.s.) | |||||||||

| Rodgers et al., 2010 [31] |

Prospective |

1572 (60) |

Initiate vs. long-term exercisers (Mean 22–51 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ) |

MV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (n.s.), EXT (−) overtime for initiates, but < to regular exercisers |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ); Initiate vs. long-term exercisers |

Manovas. Total N from 6 samples: initiates (60, 134, 38, 84), regular exercisers (202, 1054) |

|

| Barbeau et al., 2009 [101] |

Prospective (1mo) |

118 (65) |

Healthy adults (Mean 19 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2) |

MV: AutMot (+), CtMot (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations; Path analysis |

|

|

BIV: AutMot (+), CtMot (n.s.) | |||||||||

| Hagger et al., 2006 [35] |

Prospective (4wk) |

261 (64) |

University students (Mean 24.9 yr) |

UK |

Relative autonomy index (based on PLOC scale) |

BIV: RAI (+) |

Self-reported exercise (frequency) |

Bivariate correlations; SEM |

|

| Hagger et al., 2006 [34] |

Prospective (4 wk) |

261 (64) |

Exercise sample of university students (Mean 24.9 yr) |

UK |

Relative autonomy index (based on PLOC Scale) |

BIV: RAI (+) |

Self-reported exercise (frequency) |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| Kwan et al., 2011[53] |

Prospective (4 wk) |

104 (58) |

Undergraduate students; active (Mean 18.2 yr) |

USA |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2) |

BIV: IM (+), ID (n.s.), INTR (n.s.), EXT (n.s.), AMOT (n.s.), RAI (n.s) |

Self-reported exercise (online diary) |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| Edmunds et al., 2007 [38] |

Prospective (uncontrolled intervention) (3mo) |

49 (84) |

Overweight/Obese patients (Mean BMI: 38.8; Mean 45 yr) on an exercise scheme |

UK |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2); Integrated regulation subscale (EMS) |

MV: IM (n.s.), INTEG (+), ID (−)*, INTR (+)*, EXT (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ); |

Bivariate correlations; Multilevel regression analysis.* ID and INTR multivariate outcomes resulted from net suppression; thus, not considered by the authors. |

|

| |

|

|

BIV: ID (+), INTR (−) |

|

|||||

| Wilson et al., 2003 [58] |

Experimental (12wk) |

53 (83) |

Adults (Mean 41.8 yr; BMI: 19.9 ± 3.0 kg/m2) |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ) |

MV: IM (+), ID (+) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations; Multiple regression analysis. IM and ID increased from pre- to post-exercise program |

|

|

BIV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (n.s.), EXT (n.s.) | |||||||||

| Sweet et al., 2009 [102] |

Experimental (12mo) |

234 (38) |

Inactive with type 2 diabetes (Mean 53 yr) on an exercise program |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ) |

MV: AutMot (+) |

Amount of PA (kcal/month) |

Bivariate correlations; Regression/Mediation analysis |

|

| |

|

BIV: AutMot (+) |

|||||||

| Fortier et al., 2011 [36] |

Experimental (13wk); RCT |

120 (69) |

Inactive patients (Mean 47.3 yr): intensive vs. brief PA intervention |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2) |

BIV: IM, ID, INTR, EXT, and RAI were not significant predictors |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| Fortier et al., 2007 [17] |

Experimental (13wk); RCT |

120 (69) |

Autonomy supportive vs brief PA counseling (Mean 47.3 yr) |

Canada |

Treatment self-regulations (TSRQ-PA) |

MV: AutMot (+) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations; Path/Mediation analysis |

|

|

BIV: AutMot (n.s.) | |||||||||

| Levy & Cardinal, 2004 [40] |

Experimental (2mo); RCT |

185 (68) |

Adults (Mean 46.8 yr); SDT-based mail intervention vs. controls |

USA |

Exercise self-regulations (EMS) |

MV: IM, INTEG, ID, INTR, EXT, and AMOT were not significant predictors |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Manovas with repeated measures |

|

| Mildestvedt et al., 2008 [68] |

Experimental (4wk); RCT |

176 (22) |

Cardiac rehabilitation patients (Mean 56 yr): SDT-based vs standard rehab treatment |

Norway |

Autonomous and controlled motivations (TSRQ) |

BIV: AutMot (+); CtMot (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (composite score); exercise intensity |

ANOVAs with repeated measures |

|

| Silva et al., 2010 [33] |

Experimental (12mo); RCT |

239 F |

OW/Obese women (Mean 38 yr); SDT-treatment vs controls |

Portugal |

Exercise self-regulations (SRQ-E) |

MV: IM (+)*, ID (n.s.), INTR (n.s.), EXT (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise: MVPA * (7-day PAR); lifestyle PA index |

Bivariate correlations; PLS analysis; Mediation analysis |

|

| BIV: IM (+), ID (+), INTR (+), EXT (n.s.) | |||||||||

| Silva et al., 2010 [32] |

Experimental (1 yr + 2y follow-up); RCT |

221 F |

OW/Obese women (Mean 38 yr); SDT-treatment vs controls |

Portugal |

Exercise self-regulations (SRQ-E) at 1 yr and 2 yr |

MV: AutMot 2 yr (+), INTR 2 yr (n.s.), EXT 2 yr (n.s.) |

2-yr self-reported exercise: MVPA (7-day PAR) |

Bivariate correlations; PLS analysis; Mediation analysis |

|

| BIV: AutMot 1 and 2 yr (+), INTR 2 yr (+), EXT 2 yr (n.s.) | |||||||||

|

II. Exercise-related psychological need satisfaction | |||||||||

| Puente & Anshel, 2010 [77] |

Cross-sectional |

238 (57) |

College students (Mean 20.4 yr) |

USA |

Basic Psychological Needs Scale (BPNS); Perceived Competence Scale (PCS) |

MV: Competence (+) |

Exercise frequency |

Bivariate correlations; SEM; Relatedness not measured. |

|

|

BIV: Autonomy (n.s.), Competence (+) | |||||||||

| Edmunds et al., 2006 [44] |

Cross-sectional |

369 (52) |

Healthy individuals (Mean 31.9 yr) |

UK |

Psychological need satisfaction (BNSWS adapted) |

MV: Autonomy (n.s.), Competence (+), Relatedness (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (total and strenuous PA; LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations; Regression analysis; mediation analysis |

|

|

BIV: Autonomy (+), Competence (+), Relatedness (+) | |||||||||

| Edmunds et al., 2006 [51] |

Cross-sectional |

339 (53) |

Symptomatic vs asymptomatic for exercise dependence (Mean 32.1 yr) |

UK |

Psychological need satisfaction (BNSWS adapted) |

BIV: Autonomy (n.s.), Competence (+), Relatedness (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (total and strenuous PA; LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations. No associations with mild/moderately intense PA |

|

| Peddle et al., 2008 [43] |

Cross-sectional |

413 (46) |

Colorectal cancer survivors (Mean 60 yr) |

Canada |

Psychological need satisfaction (PNSE) |

BIV: Autonomy (+), Competence (+), Relatedness (+) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| McDonough et al., 2007 [50] |

Cross-sectional |

558 (72) |

Recreational dragon boat paddlers (Mean 45 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise need satisfaction (PNSE) |

MV: Autonomy (−), Competence (+) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations; SEM |

|

|

BIV: Autonomy (n.s.), Competence (+), Relatedness (n.s.) | |||||||||

| Sebire et al., 2009 [19] |

Cross-sectional |

410 (71) |

Exercisers (Mean 41.4 yr) |

UK |

Exercise need satisfaction (PNSE) |

BIV: Exercise need satisfaction (composite score) (+) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| Milne et al., 2008 [87] |

Cross-sectional |

558 F |

Breast cancer survivors (Mean 59 yr) |

Australia |

Perceived competence (PCS) |

MV: Competence (+) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ); Exercise categories (meeting vs. not meeting guidelines) |

Anovas; Hierarchical regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: Competence (+) | |||||||||

| Halvary et al., 2009 [76] |

Cross-sectional |

190 (44) |

Healthy adults (Mean 21.8 yr) |

Norway |

Perceived competence (PCS) |

MV: Competence (n.s.) |

Exercise frequency and duration |

Bivariate correlations; SEM/Mediation analysis |

|

|

BIV: Competence (+) | |||||||||

| Vlachopoulos & Michailidou, 2006 [103] |

Cross-sectional |

508 (50) |

Greek adults (Mean 30 yr) |

Greece |

Psychological needs satisfaction in exercise (BPNES) |

MV: Autonomy (n.s.), Competence (+); Relatedness (n.s.) |

Exercise frequency |

SEM |

|

| Markland & Tobin, 2010 [88] |

Cross-sectional |

133 F |

Exercise referral scheme clients |

UK |

Autonomy need (LCE); Perceived Competence (IMI); Relatedness (8-item scale) |

BIV: Autonomy (+), Competence (+), Relatedness (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| Russell & Bray, 2009 [98] |

Cross-sectional and prospective (6 + 6wk) |

68 (13) |

Cardiac rehabilitation outpatients (Mean 64.9 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise need satisfaction (PNSE) |

BIV: Autonomy (n.s.), Competence (+)*, Relatedness (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (7Day-PAR) at 3wk and 6wk* follow-up |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| Barbeau et al., 2009 [101] |

Prospective (1mo) |

118 (65) |

Healthy adults (Mean 19 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise need satisfaction (PNSES) |

BIV: Autonomy (+), Competence (+), Relatedness (+) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| Hagger et al., 2006 [34] |

Prospective (4 wk) |

261 (64) |

Exercise sample of university students (Mean 24.9 yr) |

UK |

Psychological need satisfaction |

BIV: Psychological need satisfaction (composite score) (+) |

Self-reported exercise (frequency). |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| Edmunds et al., 2007 [38] |

Prospective (uncontrolled intervention) (3mo) |

49 (84) |

OW/Obese patients (BMI: 38.75; Mean 45 yr) |

UK |

Psychological need satisfaction (PNSS) |

MV: Autonomy (n.s.), Competence (n.s.); Relatedness (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ); (Increase in relatedness overtime) |

Multilevel regression analysis; Paired T-tests |

|

| Fortier et al., 2007 [17] |

Experimental (13 wk); RCT |

120 (69) |

Healthy adults (Mean 47.3 yr) |

Canada |

Perceived Competence (PCES) |

MV: Competence (+) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Path analysis; Mediation analysis |

|

| Levy & Cardinal, 2004 [40] |

Experimental (2mo); RCT |

185 (68) |

Adults (Mean 46.8 yr); SDT-based mail intervention vs. controls |

USA |

Perceived autonomy satisfaction (LCE) |

MV: Autonomy (+ F), Competence (n.s.), Relatedness (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Manovas with repeated measures |

|

| Silva et al., 2010 [33] |

Experimental (12mo); RCT |

239 F |

OW/Obese women (Mean BMI: 31.5; Mean 38 y); SDT-based weight loss treatment vs controls |

Portugal |

Perceived autonomy satisfaction (LCE); Competence (IMI) |

BIV: Autonomy (+), Competence (+) |

Self-reported exercise: MVPA (7-day PAR); lifestyle PA index |

Bivariate correlations |

|

|

III. Exercise motives and related measures | |||||||||

| Ingledew et al., 2009 [79] |

Cross-sectional |

251 (52) |

University Students (Mean 19.5 yr) |

UK |

Exercise motives (EMI-2) |

MV: Intrinsic motives: Stress management (+), Affiliation (+), Challenge (+); Extrinsic: Health/fitness (+); body-related (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (measure analogous to LTEQ) |

Partial Least Squares Analysis (PLS); Mediation analysis |

|

| Ingledew & Markland, 2008 [46] |

Cross-sectional |

252 (48) |

Office workers (Mean 40 yr) |

UK |

Exercise motives (EMI-2) |

BIV: Intrinsic motives (n.s.), Extrinsic motives: health/fitness (+) and body-related (−) |

Self-reported exercise (measure analogous to LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| Frederick & Ryan, 1993 [59] |

Cross-sectional |

376 (64) |

Healthy individuals (Mean 39 yr) |

USA |

Exercise motives (MPAM) |

Intrinsic motives: interest/enjoyment (+); competence (+); Extrinsic motives: body-related (+) |

Self-reported exercise (levels, intensity) |

Differences between PA categories; correlations and Manovas |

|

| Frederick et al., 1996 [104] |

Cross-sectional |

118 (68) |

College students (Mean 22 yr) |

USA |

Exercise motives (MPAM-r) |

MV: Extrinsic: body-related (+ M) |

Self-reported exercise: frequency, volume |

Bivariate correlations; Multiple regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: Intrinsic motives (+ F), Extrinsic: body-related (+ M) | |||||||||

| Buckworth et al., 2007 [30] a |

Cross-sectional |

184;220 (60) |

University students (Mean 18–22 yr) |

USA |

Exercise motives (EMI and IMI; total and subscales) |

Intrinsic motives (except choice) (+); Extrinsic motives (except tangible rewards) (+) |

Exercise stages of change |

Anovas and profile analysis |

|

| Sebire et al., 2009 [19] |

Cross-sectional |

400 (73) |

Exercisers (Mean 41.4 yr) |

UK |

Exercise goal content (GCEQ) |

MV: Intrinsic motives (+) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations; Hierarchical regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: Intrinsic motives (+) | |||||||||

| Segar et al., 2006 [64] |

Cross-sectional |

59 F |

Healthy adults (Mean 45.6 yr) |

USA |

Body and non-body shape motives for exercise (via inductive, qualitative methods) |

BIV: Body motives (−); non-body shape motives (+). |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Hierarchical regression analysis |

|

| Sit et al., 2008 [105] |

Cross-sectional |

360 F |

Chinese adults (30–59 yr) |

China |

Exercise motives (MPAM-r) |

MV: Intrinsic motives : competence/challenge (+), interest/enjoyment (+); Extrinsic: fitness/health (+); appearance (n.s.) |

Exercise stages of change |

Manovas |

|

| Davey et al., 2009 [106] |

Cross-sectional |

134 (66) |

Employees (estimated mean age between 25–44 yr) |

New Zeland |

Exercise motives (based on MPAM-r and SMS) |

MV: Intrinsic motives: enjoyment (+), competence/challenge (+); Extrinsic: appearance (−); Fitness (n.s.) |

Total number of steps in 3wk |

Multiple regression analysis |

|

| Segar et al., 2008 [65] |

Prospective |

156 F |

Healthy women (Mean 49.3 yr) |

USA |

Extrinsic and Intrinsic goals (based on a list of goals and on cluster analysis) |

MV: Intrinsic goals (+); Extrinsic goals: weight maintenance/toning (−); health benefits (−) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Linear mixed model |

|

| Ingledew et al., 1998 [107] |

Prospective (3mo) |

425 (34) |

Government employees (Mean 40 yr) |

UK |

Exercise motives (EMI-2) |

MV: Intrinsic motives: enjoyment (+); Extrinsic: body-related (+ action; - maintenance); health pressures (+ preparation; - action/maintenance) |

Exercise stages of change |

Discriminant function analysis |

|

| Ryan et al., 1997 [27] a |

Prospective (10wk) |

40 (80) |

University students and employees (Mean 21 yr) |

USA |

Exercise motives (MPAM) |

MV: Intrinsic motives: enjoyment (+), competence (+); body-related motives (n.s.) |

Reduced dropout and attendance to exercise classes |

Manovas and multiple regressions |

|

| Ryan et al., 1997 [27] b |

Prospective (10wk) |

155 (57) |

New fitness center members (Mean 19.5 yr) |

USA |

Exercise motives (MPAM-R) |

MV: Intrinsic motives: enjoyment (+), competence (+), social interactions (+); Extrinsic motives: fitness (n.s.), appearance (n.s.) |

Attendance to and duration of exercise workout |

Manovas and multiple regressions |

|

| Buckworth et al., 2007 [30] b |

Experimental (10wk) |

142 (66) |

College Students (Mean 21.3 yr) |

USA |

Exercise motives (EMI and IMI); |

BIV: Intrinsic motives: effort/competence (+) and interest/enjoyment (+); Extrinsic motives: appearance (+) * |

Exercise patterns (from stable inactive to stable active); Activity vs. Lecture (no activity) Classes * |

Anovas with repeated measures. |

|

|

IV. Perceived need support | |||||||||

| Peddle et al., 2008 [43] |

Cross-sectional |

413 (46) |

Colorectal cancer survivors (Mean 60 yr) |

Canada |

Perceived need support (PAS, based on HCCQ-short) |

BIV: Need support (+) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| Milne et al., 2008 [87] |

Cross-sectional |

558 F |

Breast cancer survivors (Mean 59 yr) |

Australia |

Perceived need support (mHCCQ) |

MV: Need support (+) BIV: Need support (+) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ); exercise categories (meeting vs. not meeting guidelines) |

Anovas; Hierarchical regression analysis |

|

| Hurkmans et al., 2010 [92] |

Cross-sectional |

271 (66) |

Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (Mean 62 yr) |

Netherlands |

Perceived need support (HCCQ-mod) |

MV: Need support (n.s.) |

Self-reported PA (SQUASH) |

Bivariate correlations; Multiple regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: Need support (n.s.) | |||||||||

| Halvary et al., 2009 [76] |

Cross-sectional |

190 (44) |

Healthy adults (Mean 21.8 yr) |

Norway |

Perceived need support (SCQ based on HCCQ) |

BIV: Need support (+) |

Exercise frequency and duration |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| Markland & Tobin, 2010 [88] |

Cross-sectional |

133 F |

Exercise referral scheme clients |

UK |

Need support (15-item scale) |

BIV: Need support (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| Puente & Anshel, 2010 [77] |

Cross-sectional |

238 (57) |

College students (Mean 20.4 yr) |

USA |

Exercise need support (SCQ) |

BIV: Need support (+) |

Exercise frequency |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| Russel & Bray, 2010 [99] |

Cross-sectional and prospective (14wk) |

53 M |

Exercise cardiac rehabilitation patients (Mean 62.8 yr) |

Canada |

Perceived need support (HCCQ-short) |

MV: Need support (n.s.) |

Exercise frequency; duration (+); volume – 7Day-PAR |

Bivariate correlations; Hierarchical regression analysis |

|

|

BIV: Need support (+) | |||||||||

| Levy et al., 2008 [108] |

Prospective (8-10wk) |

70 (37) |

Injured exercisers in rehabilitation (Mean 33 yr; 69% recreational) |

UK |

Perceived need support (HCCQ) |

MV: Need support (+) a, c |

Exercise adherence: a clinical, b home-based; c attendance |

Bivariate correlations; Manovas |

|

|

BIV: Need support (+) a, c | |||||||||

| Edmunds et al., 2007 [38] |

Uncontrolled Prospective (3mo) |

49 (84) |

OW/Obese patients (BMI: 38.75; Mean 45 yr) on an exercise scheme |

UK |

Perceived need support (HCCQ) |

MV: Need support (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ); |

Multilevel regression analysis |

|

| Fortier et al., 2007 [17] |

Experimental (13 wk); RCT |

120 (69) |

Autonomy supportive vs. brief PA counseling (Mean 47.3 yr) |

Canada |

Perceived need support (HCCQ) |

BIV: Need support |

Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Bivariate correlations |

|

| Mildestvedt et al., 2008 [68] |

Experimental (4wk); RCT |

176 (22) |

Cardiac rehabilitation patients (Mean 56 yr): autonomy supportive vs. standard rehab |

Norway |

Perceived need support (mHCCQ) |

MV: Need support (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (composite score); exercise intensity |

Manovas with repeated measures |

|

| Silva et al., 2010 [33] |

Experimental (12mo); RCT |

239 F |

OW/Obese women (Mean BMI: 31.5; Mean 38 y): SDT-based WL treatment vs. controls |

Portugal |

Perceived need support (HCCQ) |

MV: Need support (+) |

Self-reported exercise: MVPA (7-day PAR); lifestyle PA index |

Bivariate correlations; PLS/mediation analysis |

|

|

BIV: Need support (+) | |||||||||

| Silva et al., 2010 [32] |

Experimental (1 yr + 2y follow-up); RCT |

221 F |

OW/Obese women (Mean BMI: 31.5; Mean 38 y): SDT-based WL treatment vs. controls |

Portugal |

Perceived need support (HCCQ) |

BIV: Need support (+) |

Self-reported exercise: MVPA (7-day PAR) |

Bivariate correlations |

|

|

V. Exercise Causality Orientations | |||||||||

| Rose et al., 2005 [56] |

Cross-sectional |

375 (51) |

Volunteers (17–60 yr) |

UK |

Exercise causality orientations (ECOS) |

MV: Autonomy O. (+), Controlling O. (− F), and Impersonal O. (−) |

Exercise stages of change |

Discriminant function analysis. Gender differences |

|

| Kwan et al., 2011[53] |

Prospective (4 wk) |

104 (58) |

Undergraduate students; active (Mean 18.2 yr) |

USA |

Exercise causality orientations (ECOS) |

BIV: Autonomy O. (+), Controlling O. (−), and Impersonal O. (n.s.) |

Self-reported exercise (online diary) |

Bivariate correlations |

|

|

VI. SDT-based Interventions and other SDT-related measures | |||||||||

| Edmunds et al., 2008 [39] |

Experimental (10wk) |

55 F |

Exercisers (Mean 21 yr) |

UK |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2); Need support (PESS); Basic needs (PNSS); Exercise attendance |

Groups: SDT-based exercise classes vs. traditional exercise classes |

Higher perceived need support, autonomy and relatedness needs; Competence (+), INTRO (+) and amotivation (−) overtime for both groups |

Higher exercise attendance |

Multilevel regression analysis |

| Fortier et al., 2007 [17] |

Experimental (13wk); RCT |

120 (69) |

Healthy adults (Mean 47.3 yr) |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (TSRQ-PA); Perceived Competence (PCES); Need Support (HCCQ); Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Groups: autonomy supportive vs. brief PA counseling |

Higher perceived need support, autonomous motivation overtime |

Higher reported exercise overtime |

Ancovas |

| Fortier et al., 2011 [36] |

Experimental (13wk); RCT |

120 (69) |

Inactive primary care patients (Mean 47.3 yr): intensive vs. brief PA counseling intervention |

Canada |

Exercise self-regulations (BREQ-2); Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Groups: autonomy supportive - intensive vs. brief PA counseling |

Higher perceived need support, autonomous motivation overtime |

Higher reported exercise overtime |

Ancovas |

| Mildestvedt et al., 2008 [68] |

Experimental (4wk); RCT |

176 (22) |

Cardiac rehabilitation patients (Mean 56 yr): autonomy supportive vs. standard rehab |

Norway |

Exercise self-regulations (TSRQ); Perceived need support (mHCCQ); Self-reported exercise |

Groups: autonomy supportive vs. standard rehab |

No significant differences |

No significant differences |

Anovas with repeated measures |

| Levy & Cardinal, 2004 [40] |

Experimental (2mo); RCT |

185 (68) |

Adults (Mean 46.8 yr); SDT-based mail intervention vs. controls |

USA |

Exercise self-regulations (EMS); Perceptions of autonomy (LCE); Competence (PSPP); Self-reported exercise (LTEQ) |

Groups: SDT-based mail vs. controls |

Women only: increase in perception of autonomy |

Women only: increase self-reported exercise |

Anovas with repeated measures |

| Silva et al., 2010 [18] |

Experimental (12mo); RCT |

239 F |

OW/Obese women (Mean BMI: 31.5; Mean 38 y); RCT |

Portugal |

Exercise self-regulations (SRQ-E); Need support (HCCQ); Perceived autonomy (LCE); Self-reported exercise (MVPA, lifestyle, steps) |

Groups: SDT-based weight loss treatment vs. controls |

Higher need supportive climate, autonomy satisfaction, IM, IDENT, INTRO |

Higher reported exercise (all measures) |

Effect sizes; T-tests |

| Silva et al., 2011 [32] | Experimental (1 yr + 2y follow-up); RCT | 221 F | OW/Obese women (Mean BMI: 31.5; Mean 38 y); RCT | Portugal | Exercise self-regulations (SRQ-E) at 1 yr and 2 yr; Need support (HCCQ); Self-reported exercise (MVPA) | Groups: SDT-based weight loss treatment vs. controls | Higher 2-yr EXT, INTRO and autonomous regulations | Higher 2-yr reported exercise | Effect sizes; T-tests |

Legend: F, female; M, male ; BIV, uni/bivariate associations; MV, multivariate associations; IM, intrinsic motivation; INTEG, integrated regulation; ID, identified regulation; INTR, introjected regulation; EXT, external regulation; AMOT, amotivation; RAI, relative autonomy index; AutMot, autonomous motivations; CtMot, controlled motivations; Autonomy O., autonomy orientation; Controlling O., controlling orientation; Impersonal O., impersonal orientation; (+), positive association; (-), negative association; (n.s.), not significant. Superscript letters are used to signal associations between specific predictors and outcomes (check the ‘significant predictors’ and ‘outcomes’ columns when applied). (*) is used when specific comments need to be made (check the ‘observations’ column on those cases).

Organization of SDT predictors

Studies were generally organized based on the self-determination theory process model, depicted in Figure 1. The goal of the present manuscript was not to test this model per se, which would involve a considerably larger analysis. Instead, we focused exclusively on relations between each of these categories of variables and exercise outcomes (described below). Results concerning exercise self-regulations are listed first, followed by findings reporting the association between psychological needs satisfaction and exercise behavioral outcomes. Next, results concerning the measures of exercise motives/goals are reported, followed by findings regarding the association between perceived need support and exercise. Exercise causality orientation studies are listed last. In addition, we also identified interventions based on SDT and analyzed their effects on exercise outcomes.

Exercise-related outcomes

Exercise behavior was evaluated through self-reported measures (e.g., 7-day Physical Activity Recall (PAR) [25], Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (LTEQ) [26]) in a total of 55 independent samples (78%). Three studies (representing 4 original samples) used accelerometry or pedometry to measure physical activity (6%). Measures of stages of change for exercise participation were employed in 13 samples (18%). A few other indicators were also used in some cases (8%), namely exercise attendance, number of exercise relapses, and exercise dropout.

Data coding and analyses

Summary tables were created based on the analysis of the available data (Tables 2 and 3). Sample characteristics (i.e., sample size, age, gender) were summarized using a tallying system and resulted in total counts (see Table 2). The percentage of independent samples presenting each characteristic from the total number of samples was also included. A summary of the evidence for each SDT-based construct was determined through a calculation of the percentage of independent samples supporting each association, based on whether the association was statistically significant or not (see Table 3). In all studies, significance level was set at 0.05. The measures of association varied across the studies’ statistical methods, as indicated in the column “observations” in Table 1, including correlation and multiple regression coefficients, t-test or ANOVA group differences (e.g., between active and inactive groups), discriminant function coefficients, and structural equation model path coefficients, among others. Because many studies included bivariate associations (or direct paths in structural models) and also multivariate associations (in regression or in structural models), these were analyzed separately (see Table 2). A sum code was built for each motivational construct based on the following classification system: Positive (++) for percentage K ≥75% and (+) for percentage K between 50-75% showing positive associations in both bivariate and multivariate tests; 0/+ or 0/- when the evidence was split between no association (0) and either positive or negative associations, respectively; and (?) for other results indicating inconsistent findings or indeterminate results due to a small number of studies available).

Table 2.

Summary of samples characteristics

| Characteristics | SamplesK(%) |

|---|---|

| Sample size |

|

| < 100 |

13 (18.0) |

| 100-300 |

38 (52.8) |

| 300-500 |

12 (16.7) |

| ≥ 500 |

9 (12.5) |

| Gender |

|

| Women only |

11 (15.3) |

| Men only |

1 (1.4) |

| Men and Women – Combined |

46 (63.9) |

| Men and Women – Separately |

14 (19.4) |

| Location |

|

| Western countries |

70 (97.2) |

| Non-western countries |

2 (2.8) |

| Mean age, years |

|

| ≤24 |

21 (29.2) |

| 25-44 |

28 (38.8) |

| 45-64 |

22 (30.6) |

| ≥ 65 |

1 (1.4) |

| Design |

|

| Cross-Sectional |

45 (62.5) |

| Longitudinal – Observational |

16 (22.2) |

| Longitudinal – Experimental |

9 (12.5) |

| Mixed Method |

2 (2.8) |

| Exercise Data Collection |

|

| Self-reported Exercise |

56 (77.8) |

| Exercise Stages of Change |

13 (18.1) |

| Accelerometry/pedometry |

4 (5.6) |

| Other* |

6 (8.3) |

| Total K | 72 |

Note: *Exercise relapses, weekly attendance, exercise adherence (home; clinical), exercise dropout.

Table 3.

Summary of associations between SDT predictors and exercise-related outcomes

| % KSupporting associations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Predictors |

# of Studies |

K |

+ |

- |

0 |

Sum code |

|

Exercise Regulations/Motivations | ||||||

| Intrinsic motivation |

26 (22) |

37 (24) |

62 (92) |

0 (0) |

38 (8) |

+ |

| Integrated regulation |

6 (3) |

8 (4) |

62 (75) |

0 (0) |

38 (25) |

+ |

| Identified regulation |

27 (24) |

38 (26) |

74 (85) |

2 (0) |

24 (15) |

+ |

| Introjected regulation |

26 (25) |

37 (27) |

30 (52) |

5 (4) |

65 (44) |

0/+ |

| External regulation |

26 (24) |

37 (26) |

0 (0) |

43 (23) |

57 (77) |

0/- |

| Amotivation |

10 (11) |

14 (13) |

0 (0) |

36 (69) |

64(31) |

0/- |

| Relative autonomy (e.g., RAI) |

8 (13) |

8 (12) |

88 (83) |

0 (0) |

12 (17) |

++ |

| Autonomous regulations |

10 (10) |

11 (11) |

91 (82) |

0 (0) |

9 (18) |

++ |

| Controlled regulations |

4 (6) |

5 (7) |

0 (0) |

60 (0) |

40 (100) |

0/- |

|

Need-Supportive Climate |

6 (11) |

6 (11) |

50 (73) |

0 (0) |

50 (27) |

+ |

|

Psychological Needs in Exercise | ||||||

| Autonomy |

4 (9) |

5 (10) |

20 (50) |

20 (0) |

60 (50) |

0/+ |

| Competence |

8 (12) |

9 (13) |

56 (92) |

0 (0) |

44 (8) |

+ |

| Relatedness |

4 (7) |

4 (8) |

0 (38) |

0 (0) |

100 (62) |

0 |

| Composite score* |

0 (2) |

0 (2) |

0 (100) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

? |

|

Exercise Motives/Goals | ||||||

| Intrinsic |

7 (5) |

8 (8) |

100 (75) |

0 (0) |

0 (25) |

++ |

| Health/fitness |

6 (1) |

6 (1) |

33 (100*) |

33 (0) |

33 (0) |

? |

| Body-related |

7 (5) |

8 (8) |

25 (63) |

25 (12) |

50 (25) |

0/+ |

|

Exercise Causality Orientations | ||||||

| Autonomy* |

1 (1) |

2 (1) |

100 (100) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

? |

| Controlling* |

1 (1) |

2 (1) |

0 (0) |

50 (100) |

50 (0) |

? |

| Impersonal* | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 100 (0) | 0 (100) | ? |

Legend: Results derived from multivariate analyses and uni/bivariate analyses (in parenthesis) are presented. K, number of samples. Positive (++) was used for percentage K ≥75% and (+) for percentage K between 50-75% for both bivariate and multivariate associations; 0/+ or 0/- when the evidence was split between no association (0) and either positive or negative associations, respectively; (?) for other results indicating inconsistent findings or indeterminate results (i.e., when only a small number of studies were available, marked with *).

Results

Characteristics of studies and samples

The 66 located studies comprised a total of 72 independent samples. The number of samples was higher than the total number of studies because some studies analyzed data originating from more than one sample (two samples: [27], [28], [29]; three samples: [30]; six samples: [31]). On the other hand, 7 studies were published using data from three original samples ([18,33,32]; [35,34]; [17,36]). A summary of the demographic characteristics of participants and samples is reported in Table 2. Samples tended to be mixed gender and included a range of populations (e.g., healthy individuals, chronic disease patients, overweight/obese individuals, exercisers), predominantly from Western cultures (97%), and mainly aged between 25–65 years-old.

From the studies eligible for this review, 53 (K = 57) analyzed associations between self-regulations and exercise behavioral outcomes, 17 studies (K = 17) investigated the relations between basic psychological needs and exercise, 12 studies (K = 15) tested the associations between motives and exercise, and 13 studies (K = 12) included measures of perceived need support and evaluated its predictive effect on exercise-related outcomes (see Table 3). Seven intervention studies, corresponding to 6 actual interventions, were identified. It should be noted that relations reported in the intervention studies were also analyzed in the other sections (e.g., regulations, need support, etc.)

Motivational predictors of exercise-related outcomes

Exercise behavioral regulations. A total of 57 samples (53 studies) analyzed associations between regulations and exercise behavior. Of these, 37 were used in cross-sectional designs, 10 in prospective designs, 7 in experimental studies, and 2 in mixed designs. Regulations were assessed with different instruments (53% with the Behavioural Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire (BREQ) and with Markland and Tobin’s revised version (BREQ-2) [37] and reported results in several ways: Relative autonomy was evaluated as a composite score (e.g., the Relative Autonomy Index (RAI), by which individual regulations are weighted and summed to give an index of the extent to which a person’s behavior is more or less autonomously regulated) in 23% of the cases (none of which were experimental designs); autonomous and controlled regulations were grouped and analyzed as two higher-level types of regulation in 21% and 14% of the cases, respectively. All major forms of regulation were assessed and discriminated in 71% of the cases.

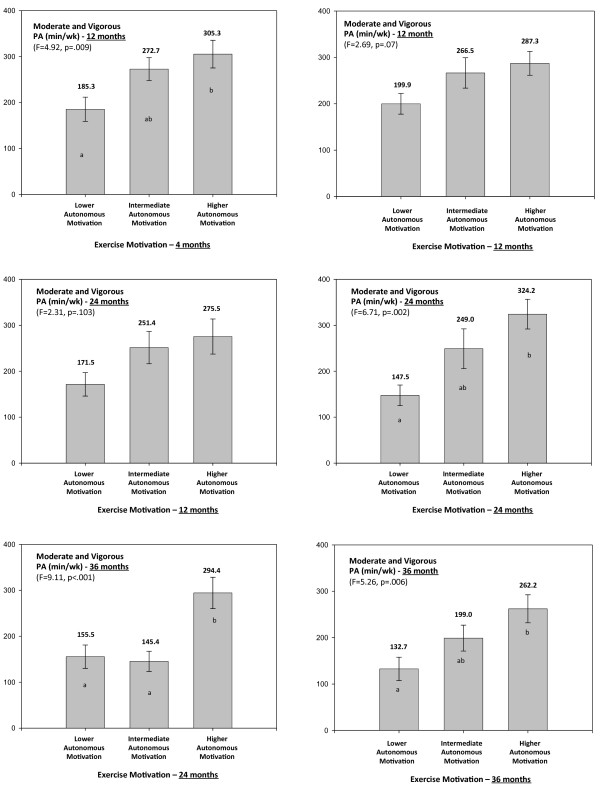

Nearly all studies using measures of relative autonomy (8 of 9 K) reported positive associations with exercise behavior while studies investigating autonomous and controlled forms of regulation (K = 11 and K = 5, respectively) also found consistent, positive associations favoring autonomous regulations as a predictor of exercise outcomes (82/91%, depending on whether bivariate or multivariate analysis is used). On the other hand, 3 independent samples (60%) showed negative associations in multivariate models for non self-determined regulations, all others (40%) showing no association. In bivariate analyses, results for controlled regulations unanimously showed no association. Results were similar across different study designs, suggesting consistent positive effects of autonomous regulations on exercise behavior, and either negative or null effects associated with controlled regulations. In one study with longer-term follow-up measurements, prospective associations between regulations and exercise behavior were reported [33] (see also Figure 2). The authors found that both 12 and 24-month autonomous regulations, but not controlled regulations, mediated the effects of a SDT-based intervention on self-reported exercise at 24 months [32].

Figure 2.

Title. Self-reported minutes of moderate and vigorous exercise per week as a function of exercise autonomous motivation. Analysis includes 141 participants of the PESO trial [67] and data reports to variables assessed at 12 months (intervention end), 24 months (1 year follow-up with no contact) and 36 months (2-year follow-up). The time-point values in exercise and motivational variables at each assessment period were used (not change). Values used for tertile-split groups of autonomous motivation were calculated including all subjects (intervention and control groups collapsed), adjusting for experimental group membership. Autonomous motivation includes the identified regulation and intrinsic motivation subscales of the Exercise Self-Regulation Questionnaire[84]. Self-reported exercise was assessed with the 7-day Physical Activity Recall interview [25] and quantifies moderate and vigorous structured physical activity (METs > 3) performed in the previous week (or typical of the previous month if previous week was atypical, see reference 27 for more details). Panels B, D, and F show cross-sectional associations (variables assessed at the same time point) and panels A, C, and E show “prospective” associations (motivation assessed one year earlier than exercise). F for one-way ANOVA with letters in bar indicating multiple comparisons with Bonferroni post-hoc tests (different letters indicate different means, p < .05).

Specific results concerning the separate autonomous types of motivation showed positive associations between identified regulation and exercise behavior in 28 samples (74%) in multivariate analyses and 22 samples (85%) in bivariate analyses. The only exception was a study by Moreno et al. where the mean value for identified regulation was lower in a group reporting 60+ min of exercise than among those who exercised less than 60 min (presumably each day; no details are provided). Of note also are the mixed results found by Edmunds et al. (2007) displaying negative associations for identified regulations in a multilevel model, but positive cross-sectional associations at each of the 3 times points. The authors indicated that the multilevel results “should be ignored as they are a consequence of net suppression” [38]; pg.737]. In 3 studies that analyzed identified regulations [36,40,39], no significant association emerged. Regarding intrinsic motivation, positive associations with exercise behavior were reported in 23 or 22 independent samples (62% or 92%), in multivariate or bivariate analyses respectively. No study reported negative associations and results were consistent independent of study design. Few studies have tested the role of integrated regulation, but it appears to positively predict exercise behavior. Of 8 samples analyzed, 62-75% found positive associations with physical activity, with increased consistency found in bivariate analyses.

In an attempt to further clarify which single self-determined type of motivation is more closely related with behavior outcomes, a comparative analysis between identified and intrinsic motivation findings was undertaken. Twenty-five studies (K = 31) reported significant associations for both variables, of which 12 K were derived from multivariate analysis, 5 K from correlational analysis, and 4 K from both types of analysis. Seven studies (K = 7) found associations for identified regulation in multivariate analysis, but only bivariate associations for intrinsic motivation [44,45,43,42,41]. Three studies/samples showed the converse [48,47,33], reporting associations for intrinsic motivation in multivariate analysis and only correlational bivariate associations for identified regulation. It should be noted that no study tested whether the differences between the association coefficients (for identified regulation vs. intrinsic motivation) with exercise were significant. Wilson et al. (2002) investigated bivariate predictors of different physical activity intensities [49] and found that at mild intensities, associations were significant only for identified regulation; for moderately intense and strenuous exercise, both identified regulation and intrinsic motivation were significant predictors. Three additional studies/samples showed significant associations only for identified regulation [50,51,38]. In another study (K = 1) this regulation was the only variable predicting fewer exercise relapses [52]. On the other hand, two studies found significant associations only for intrinsic motivation [54,53].

For integrated regulation, only 6 studies (K = 8) were available. Comparing results for integrated versus identified regulations no differences were found in the patterns of association for all but one study [85] where there was a significant bivariate association with exercise for integrated but not identified regulation. Comparing results between integrated regulation and intrinsic motivation, two studies show integrated regulation, but not intrinsic motivation, as a significant predictor of exercise in multivariate models [41,38] whereas in a different study the opposite trend was observed using bivariate associations [28].