Abstract

The class Bdelloidea of the phylum Rotifera is the largest well studied eukaryotic taxon in which males and meiosis are unknown, and the only one for which these indications of ancient asexuality are supported by cytological and molecular genetic evidence. We estimated the rates of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions in the hsp82 heat shock gene in bdelloids and in facultatively sexual rotifers of the class Monogononta, employing distance based and maximum likelihood methods. Relative-rate tests, using acanthocephalan rotifers as an outgroup, showed slightly higher rates of nonsynonymous substitution and slightly lower rates of synonymous substitution in bdelloids as compared with monogononts. The opposite trend, however, was seen in intraclass pairwise comparisons. If, as it seems, bdelloids have evolved asexually, an equality of bdelloid and monogonont substitution rates would suggest that the maintenance of sexual reproduction in monogononts is not attributable to an effect of sexual reproduction in limiting the load of deleterious nucleotide substitutions.

There are many hypotheses, but no general agreement, as to why sexual reproduction is so widespread in eukaryotes and why most populations that become entirely asexual, even if initially successful, suffer early extinction (1–10). Although theoretical models have helped to define the conditions under which various hypotheses might be valid, what has been lacking is an experimental system with characteristics that would allow critical testing of hypotheses and which might also suggest novel ones. A taxon that has evolved asexually for many millions of years would therefore be of great interest. The class Bdelloidea of the phylum Rotifera, comprising some 360 described species, seems to be such a taxon.

Bdelloid rotifers are abundant invertebrate animals of worldwide distribution, mainly in fresh-water and moist-terrestrial habitats. Individuals range from about 0.1 to 1 mm in length and have muscles; ganglia; tactile and photosensitive sensory organs; structures for feeding, swimming, and crawling; digestive and secretory organs; and ovaries.

Despite much study of field and laboratory populations since bdelloid rotifers were described by Leeuwenhoek more than 300 years ago, the class Bdelloidea seems to be entirely female, without males or hermaphrodites (11–13). Where oogenesis has been investigated, eggs are produced from oocytes by two mitotic divisions, without chromosome pairing and without reduction in chromosome number, with each oocyte yielding one egg and two polar bodies (14, 15). Consistent with this apparent lack of meiosis, chromosomes without morphological homologues are present in bdelloid karyotypes (14–16).

The group most closely related to Bdelloidea is the rotifer class Monogononta, comprising some 1,100 described species (17–21). Like bdelloids, monogonont rotifers are abundant free-living animals a few tenths of a millimeter long with worldwide distribution, mainly in fresh- and brackish-water habitats. Monogononts reproduce sexually and asexually. Female monogononts are diploid and usually produce eggs from oocytes by one mitotic division, giving a polar body and a diploid egg that develops into an asexual female like its parent. In response to environmental stimuli, such females produce diploid daughters that make exclusively haploid eggs by meiosis. If unfertilized, these eggs develop into highly reduced haploid males that, by mating with females bearing haploid eggs, give rise to females that reinitiate the asexual cycle (22, 23).

Bdelloid remains have been reported in 30–40-million-year-old amber (24) and measurements of DNA sequence divergence suggest that bdelloids and monogononts separated well before that (19, 20, 25). Bdelloids and monogononts seem to be similar in genomic DNA content, with about 109 bp in the species that have been studied (26, 27). They also have comparable fecundity and generation times, with 16–32 oocytes per ovary and an average of ≈2–3 weeks between generations under favorable conditions (26, 28–32).

Two other groups within the phylum are the Acanthocephala, with ≈1,000 species, and the Seisonidea, with only two known species (17, 33, 34). Acanthocephalans are large endoparasitic rotifers with a life cycle that alternates between a vertebrate and an arthropod host. Seisonid rotifers only are found attached to only a particular genus of marine crustaceans. Acanthocephalans and seisonids are dioecious and are obligately sexual. Sequencing studies of the hsp82 heat shock gene in monogonont, acanthocephalan, and seisonid rotifers reveal the presence in individual genomes of two closely similar copies of the gene, as is characteristic of alleles in sexually reproducing diploids (refs. 25 and 35 and unpublished data).

Recently, additional evidence that bdelloid rotifers evolved asexually has been obtained from sequence studies of hsp82 and other genes in individual bdelloid and monogonont rotifers of diverse species (25). As would be expected if bdelloids evolved for many millions of years without meiosis or homologous recombination, individual bdelloid genomes seem to lack closely similar pairs of the gene and instead contain highly divergent copies that may be assigned to one or the other of two ancient lineages that separated before the radiation of modern bdelloids and after the separation of bdelloids from monogononts, during the interval when sex was presumably lost. Two such ancient lineages, both represented in individual bdelloid genomes, also are found for the gene for the TATA/binding protein.

The conclusion that bdelloids are ancient asexuals is supported further by the remarkable finding that, unlike other rotifers or any other eukaryote tested, bdelloids lack retrotransposons, consistent with the expectation that deleterious nuclear parasites will not be present in ancient asexuals (36, 37).

Here we report comparisons of nucleotide substitution rates in the hsp82 gene of bdelloids and monogononts that bear on the effect of asexual reproduction on the evolution of mutation rates and on mutational hypotheses for the prevalence of sexual reproduction.

Materials and Methods

Sequences Examined.

Sequences of hsp82 from two acanthocephalan rotifers, Oligacanthorhynchus tortuosa and Oncicola sp. (order Oligacanthorynchida), were determined by direct PCR sequencing of DNA provided by M. García-Varela (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Federal District, Mexico City). The remaining sequences that were analyzed have been described (20, 25) and are from the following species: Seisonida, Seison nebaliae; Acanthocephala, Moniliformis moniliformis (order Moniliformida); Monogononta, Brachionus plicatilis strain AUS, Brachionus calyciflorus (order Ploima), Eosphora ehrenbergi (order Ploima), and Sinantherina socialis (order Flosculariacea); Bdelloidea, Philodina roseola (family Philodinidae), Habrotrocha constricta (family Habrotrochidae), and Adineta vaga (family Adinetidae). The same 870- to 879-bp coding segment of hsp82, corresponding to Drosophila melanogaster codons 13–302 (38), was examined in all cases.

For each bdelloid species, the sequences that were analyzed were those present in the genome of a single individual, having been amplified and cloned from the DNA of a small population recently grown from a single egg. Individual bdelloid genomes contain multiple diverged copies of hsp82 (four in P. roseola, three in H. constricta, and three in A. vaga). Each copy may be assigned to one or the other of two lineages, designated A and B (25), that arose before the radiation of modern bdelloids. For bdelloids, calculations of the ratio of synonymous to nonsynonymous substitution rates (Table 1) were based on the 21 possible pairwise interspecies comparisons of the eight hsp82 sequences of the A lineage: Pr1, Pr2, Hc1, Hc2, Hc3, Av1, Av2, and Av3. There are no interspecies pairs within the B lineage in these three rotifer species. All other calculations used all 10 bdelloid hsp82 sequences.

Table 1.

Ratios of synonymous to nonsynonymous substitution rates in rotifers estimated from intraclass comparisons

| Bdelloidea | Monogononta | Acanthocephala | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Li | 10.7 (2.0) | 8.9 (2.5) | 26.2 (3.3) |

| YN | 36.4 (11.8) | 28.6 (9.7) | 61.1 (22.7) |

| GY | 20.1 (4.5) | 18.0 (1.2) | 52.7 (8.5) |

Values (with standard deviations) are average ratios of synonymous to nonsynonymous substitution rates. Ratios estimated according to Li (41) are based on substitutions at 4-fold degenerate sites; ratios estimated according to Yang and Nielsen (YN; ref. 44) and Goldman and Yang (GY; ref. 46) are based on total synonymous substitutions.

Most of the differences between rotifer hsp82 genes are synonymous and all copies seem to be functional, being free of stop codons and frame shifts. Approximately one-fifth of the sequenced amino acid sites in bdelloids and in monogononts are polymorphic and are largely the same sites in the two classes. The sequences display a moderate degree of codon bias, with an effective number of codons (39) ranging from 30 to 37, intermediate between the values for hsp82 in D. melanogaster and humans (40). With the exception of atypically high usage of codons with G or C at degenerate sites in the monogonont B. plicatilis (20, 40), there is little difference in codon usage between bdelloids and monogononts. Excluding B. plicatilis, coding-strand composition within the region of hsp82 analyzed is nearly identical in bdelloids and monogononts, with average A, T, G, and C composition of 40, 27, 19, and 14%, respectively.

Computations.

Sequences were aligned as described (20); regions with gaps were not excluded. Numbers of nucleotide differences per site at 4-fold degenerate sites between aligned sequences were counted by using the procedure of Li (41) and Pamilo and Bianchi (42) as implemented in the diverge program of the Wisconsin Package 10.0 (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, WI) but without adjustment for multiple hits. Unadjusted numbers of amino acid differences per codon were counted with the distances program.

Substitutions per site at 4-fold degenerate sites, adjusted for multiple hits and taking account of transition/transversion bias, were determined by the methods of Li (41) and Pamilo and Bianchi (42) implemented in the mega package (43). Differences at 4-fold degenerate sites are slower to saturate and less sensitive to transition-transversion bias than are differences at 2- and 3-fold degenerate sites and their use requires no assumptions regarding the relative weighting of codon degeneracy classes. The use of total synonymous sites, however, provides more data for analysis and, for maximum likelihood estimates, the problem of weighting degeneracy classes does not arise.

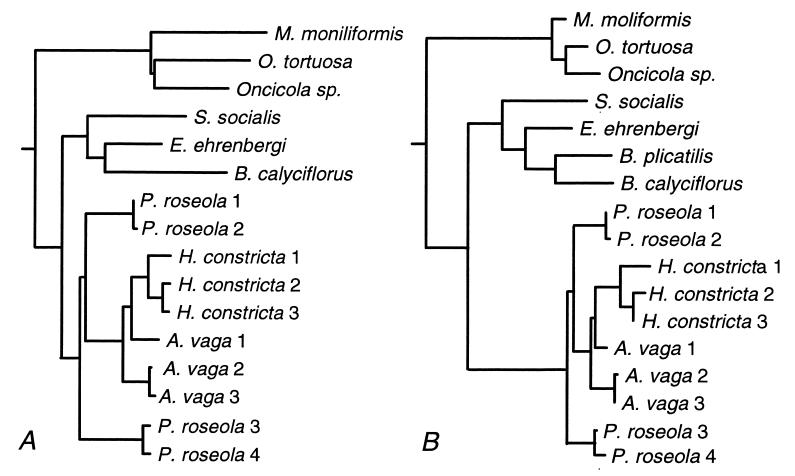

Substitutions per total synonymous (including 4-, 2-, and 3-fold) site and per nonsynonymous site, adjusted for multiple hits and taking account of transition/transversion bias, were determined by two methods: (i) the distance model of Yang and Nielsen (44) implemented in PAML 3.0a (45), with equilibrium codon frequencies calculated for each pairwise comparison from the average nucleotide frequency at each of the three codon positions; and (ii) the maximum likelihood model of Goldman and Yang (46) implemented in paml, with equilibrium codon frequencies calculated from the overall averages of the four nucleotide frequencies, and with transition/transversion bias estimated from the data. The ratio of synonymous to replacement substitutions was allowed to vary among all branches of a phylogenetic tree that includes all 11 rotifer species listed above and is based on morphological and molecular data (refs. 18–21 and 25; Fig. 3), and with transition-transversion bias estimated from the data. Relevant parameters in the program codeml were runmode = 0, CodonFreq = 1, and model = 1.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic trees for hsp82 sequences, with branch lengths proportional to synonymous (A) and nonsynonymous (B) substitutions, as estimated by the maximum likelihood method of Goldman and Yang (46). Numbers after bdelloid species names designate particular copies of hsp82 (25). The outgroup Seison nebaliae is not shown.

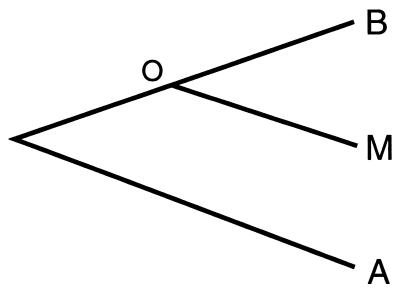

Relative-rate tests (47, 48) were used to compare the rates of nucleotide and amino acid change during evolution from the common bdelloid-monogonont ancestor to modern bdelloids and to modern monogononts, using acanthocephalan rotifers as the outgroup. Referring to the three-taxon tree of Fig. 1, the rate for the path between the common ancestor and bdelloids is OB = (BM + BA − MA)/2 and the average over all combinations of one bdelloid, one monogonont, and one acanthocephalan sequence is OBavg = Σ[(BiMj + BiAk − MjAk)/2]/(ninjnk). The monogonont B. plicatilis was not used in computing synonymous rates because of its anomalously high GC content at synonymous sites. Maximum-likelihood ratio tests of three-taxon trees were performed on amino acid translations by using hyphy 0.71 [S. V. Muse (North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC) and S. L. Kosakovsky Pond (University of Arizona, Tuscon, AZ)] with all amino acid changes weighted equally and with changes weighted according to the Dayhoff matrix.

Figure 1.

Three-taxon tree used in relative-rate tests. The designations B, M, A, and O represent bdelloids, monogononts, acanthocephalans, and the common bdelloid-monogonont ancestor, respectively.

Results

The Ratio of Synonymous to Nonsynonymous Rates Estimated from Intraclass Comparisons.

Intraclass comparisons of hsp82 sequences reveal a large excess of synonymous over nonsynonymous substitutions in bdelloids, monogononts, and acanthocephalans (Table 1). Most nonsynonymous mutations therefore have been eliminated by selection, consistent with the high degree of amino acid sequence conservation in HSP82 in other eukaryotes (38, 49) and with the preponderance of deleterious mutations over advantageous ones in most proteins (35, 50). Each of the three methods of estimation give a slightly greater value of the ratio of synonymous to nonsynonymous rates for bdelloids as compared with monogononts, although in no case is the difference greater than the average standard deviation of the individual values (Table 1). The estimates for acanthocephalans, however, are clearly higher than those for the other two classes of rotifers.

Synonymous and Nonsynonymous Rates Estimated from Interclass Comparisons.

The intraclass comparisons presented in Table 1 do not take account of substitutions during the period before the separation of the most distantly related sequences being compared and they allow comparison only with respect to the ratio of synonymous to nonsynonymous substitution rates. Therefore, relative-rate tests using acanthocephalan rotifers as an outgroup were performed so as to obtain estimates of the separate rates of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution in bdelloid and monogonont lineages during the interval since they diverged from their common ancestor.

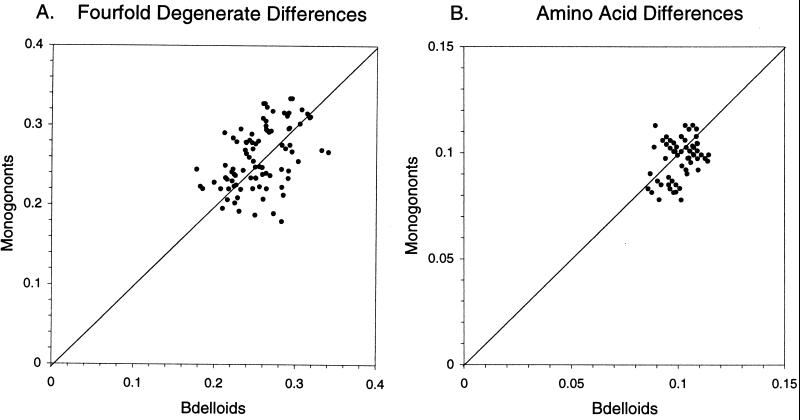

To inspect the data without adjustment for multiple hits or codon usage, relative-rate tests first were performed by using unadjusted differences at 4-fold degenerate sites and differences at amino acid sites. Fig. 2 presents scatter plots of the differences along lineages leading from the common ancestor to bdelloids (OB) and to monogononts (OM). The symmetrical distribution of data points indicates that the data set is free of conspicuously anomalous 4-fold degenerate and amino acid differences along any individual bdelloid or monogonont lineage. Although this simple approach takes no account of multiple hits, the equal distribution of data points on both sides of the line of bdelloid–monogonont equality and the average values given in Table 2 reveal no consistent difference between bdelloid and monogonont lineages in unadjusted 4-fold degenerate differences or in amino acid differences.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of unadjusted distances OB (bdelloids) and OM (monogononts) between the common bdelloid-monogonont ancestor and bdelloids or monogononts, respectively, based on 4-fold degenerate differences (A) and amino acid differences (B). Each point is obtained by the method of relative-rate tests for an individual set of bdelloid, monogonont, and acanthocephalan hsp82 sequences, except that the B. plicatilis sequence was not used for calculations of substitution per 4-fold degenerate site.

Table 2.

Synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates in rotifer lineages estimated from relative-rate tests

| OBavg | OMavg | OAavg | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synonymous | |||

| 4-fold (uncorrected) | 0.255 (0.034) | 0.260 (0.039) | 0.387 (0.036) |

| Li (4-fold) | 0.363 (0.159) | 0.533 (0.182) | 1.01 (0.15) |

| YN (total) | 1.12 (0.57) | 1.37 (0.60) | 2.40 (0.56) |

| GY (total) | 0.764 (0.112) | 1.12 (0.28) | 2.08 (0.14) |

| Nonsynonymous | |||

| aa (uncorrected) | 0.101 (0.007) | 0.100 (0.010) | 0.145 (0.006) |

| Li | 0.081 (0.005) | 0.072 (0.008) | 0.106 (0.007) |

| YN | 0.072 (0.006) | 0.073 (0.008) | 0.095 (0.009) |

| GY | 0.089 (0.012) | 0.075 (0.012) | 0.115 (0.011) |

Values (with standard deviations) are averages of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates along paths from the common bdelloid-monogonont ancestor (O) to bdelloids (B), to monogononts (M), or to acanthocephalans (A). Uncorrected 4-fold degenerate and amino acid differences are as described in the text. Synonymous rates estimated according to Li (41) are based on substitutions at 4-fold degenerate sites; rates estimated according to Yang and Nielsen (YN; ref. 44) and Goldman and Yang (GY; ref. 46) are based on total synonymous substitutions. Distance measures are averaged over all one-bdelloid, one-monogonont, and one-acanthocephalan relative-rate tests. Maximum likelihood measures are averages of branch lengths from the common bdelloid-monogonont ancestor to each hsp82 sequence, as depicted in Fig. 3.

Neither is any clearly significant difference found between bdelloid and monogonont lineages when multiple hits and codon usage are considered in estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution by any individual method (Table 2). Along a given path (OB, OM, or OA), all three methods of estimation give nearly the same values for nonsynonymous substitution rates but more widely differing values of synonymous rates, depending on how they deal with multiple hits and codon usage.

All three methods give slightly lower synonymous rates for bdelloids (by about 20–30%), and two of the three estimates of nonsynonymous rates are slightly lower for monogononts (by about 10–20%). This trend may be seen in the differences between bdelloid and monogonont branch lengths in the maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees of Fig. 3. As mentioned above, however, intraclass comparisons show the opposite trend (Table 1) and, being based on less divergent sequences, are less dependent on methods of adjustment for multiple hits.

Nonsynonymous rates along bdelloid and monogonont lineages were compared further at the amino acid level by examining maximum likelihood scores for each three-taxon bdelloid–monogonont–acanthocephalan or bdelloid–monogonont–seison tree with and without imposing the condition of equal rates. No tree was found for which the constraint of equal bdelloid and monogonont rates significantly reduced the likelihood scores.

Discussion

Using hsp82 coding sequences from three bdelloid species (representing three of the four families of class Bdelloidea), four monogonont species (representing two of the three orders of class Monogononta), and three species of Acanthocephala (representing two orders of Acanthocephala), we used intraclass sequence comparisons to estimate the ratio of synonymous to nonsynonymous nucleotide substitution rates in each rotifer class. We used relative-rate tests to estimate synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates in bdelloids and in monogononts during evolution from their common ancestor, using three species of acanthocephalans as outgroups. In addition, we obtained maximum likelihood estimates of the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions in hsp82 along each branch of a phylogenetic tree.

Only small differences between bdelloid and monogonont substitution rates were found by any method. The ratio of synonymous to nonsynonymous substitutions was slightly less for bdelloids when estimated from interclass comparisons, but the reverse was the case when the ratio was estimated from intraclass comparisons. The ratio for acanthocephalans is clearly greater than that for bdelloids and monogononts and seems to result mainly from a higher synonymous rate. It seems unwarranted, however, to ascribe the difference to any particular cause, because acanthocephalans differ greatly from bdelloids and monogononts not only in reproductive mode, but also in many other respects, being obligate parasites of enormous reproductive capacity and, in the species we examined, having warm-blooded hosts.

The close similarity of synonymous substitution rates in bdelloids and monogononts taxa that are similar in many respects, is noteworthy. Under deterministic conditions and assuming that mutations are generally deleterious, selection against alleles that increase the mutation rate will be stronger in asexuals than in sexuals, all else being equal (51–54). This increased selection is because, in asexuals, such alleles remain linked to the genomes in which they cause mutation, eventually driving clones containing them to extinction. In sexuals, however, these alleles soon segregate away. The close similarity of bdelloid and monogonont synonymous rates therefore suggests that, despite presumably stronger selection against mutator alleles in bdelloids, mutation rates in both rotifer classes may be close to some lower limit, as would result from the physical inaccessibility or steeply rising metabolic cost of further increasing the fidelity of DNA replication (55–58).

Our results also have implications for hypotheses to explain the preponderance of sexual taxa over asexual ones and for the early extinction of most populations that become asexual. Most of these hypotheses seek to explain the advantage of sex as an effect of genetic exchange between individuals in accelerating the production of advantageous new genotypes and facilitating adaptation to altered selection or in limiting the accumulation of deleterious mutations (6, 7, 10). It is to the latter group of hypotheses that our estimates of nucleotide substitution rates are relevant. If, as might be envisaged under stochastic (59) or deterministic mutational models (6, 7, 60), sexual reproduction limits the deleterious load of nucleotide substitutions in monogononts and thereby prevents their extinction, how can we explain the evolutionary success of the Bdelloidea?

It might be supposed that bdelloids have reduced their nucleotide mutation rate to a value substantially below that of monogononts. This possibility, however, seems to be ruled out by our finding of little if any significant difference between bdelloids and monogononts in synonymous substitution rates. Alternatively, one might speculate that deleterious nucleotide substitutions are better tolerated in bdelloids than they are in monogononts, owing to some factor peculiar to bdelloids. We see no indication of this possibility in estimates of nonsynonymous substitution rates and know of no evident reason why it should be so. If our results for hsp82 are applicable to bdelloid and monogonont genomes in general, and if sexual reproduction keeps monogononts from becoming extinct, it seems unlikely that it does so by limiting the deleterious load of nucleotide substitution.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ben Normark for discussions at an early stage of this article; Irina Arkhipova, James Crow, Alex Kondrashov, Jessica Mark Welch, and Richard Thomas for critically reading the manuscript; and the National Science Foundation Eukaryotic Genetics Program for support. D.M.W. was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research grant. This article is dedicated to DeLill Nasser.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Darlington C D. The Evolution of Genetic Systems. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayr E. Animal Species and Evolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 3.White M J D. Modes of Speciation. San Francisco: Freeman; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell G. The Masterpiece of Nature: The Evolution and Genetics of Sexuality. Berkeley, CA: Univ. of California Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berbee M L, Taylor J W. In: The Fungal Holomorph: Mitotic, Meiotic, and Pleomorphic Speciation in Fungal Systematics. Reynolds D R, Taylor J W, editors. Wallingford, U.K.: CAB International; 1993. pp. 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kondrashov A S. J Hered. 1993;84:372–387. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crow J F. Dev Genet. 1994;15:205–213. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020150303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raikov I B. Eur J Protistol. 1995;31:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Judson O P, Normark B B. Trends Ecol Evol. 1996;11:41–46. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)81040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurst L D, Peck J R. Trends Ecol Evol. 1996;11:46–52. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)81041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leeuwenhoek A. Philos Trans R Soc London. 1677;12:821–831. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudson C T, Gosse P H. The Rotifera or Wheel-Animalcules. Green, London: Longmans; 1886. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ricci C. Hydrobiologia. 1987;147:117–127. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu W S. Biol Bull. 1956;111:364–374. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu W S. Cellule. 1956;57:283–296. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mark Welch J L, Meselson M. Hydrobiologia. 1998;387/388:403–407. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace R L, Snell T W. In: Ecology and Classification of North American Freshwater Invertebrates. Thorp J H, Covich A P, editors. San Diego: Academic; 1991. pp. 187–248. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melone G, Ricci C, Segers H, Wallace R L. Hydrobiologia. 1998;387/388:101–107. [Google Scholar]

- 19.García-Varela M, de Leon P P, de la Torre P, Cummings M P, Sarma S S S, Laclette J P. J Mol Evol. 2000;50:532–540. doi: 10.1007/s002390010056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mark Welch D B. Invert Biol. 2000;119:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sørensen M V, Funch P, Willerslev E, Hansen A J, Olesen J. Zool Anz. 2000;239:297–318. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilbert J J. In: Reproductive Biology of the Invertebrates. Adiyodi K G, Adiyodi R G, editors. Vol. 1. New York: Wiley; 1983. pp. 181–209. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallace R L. In: Encyclopedia of Reproduction. Knobil E, Neill J D, editors. Vol. 4. San Diego: Academic; 1998. pp. 290–301. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poinar G O, Jr, Ricci C. Experientia. 1992;48:408–410. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mark Welch D B, Meselson M. Science. 2000;288:1211–1215. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pagani M, Ricci C, Redi C A. Hydrobiologia. 1993;255/256:225–230. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mark Welch D B, Meselson M. Hydrobiologia. 1998;387/388:395–402. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ricci C. Atti Soc Sci Nat Museo Civ Stor Nat Milano. 1976;117:144–148. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ricci C. Mem Ist Ital Idrobiol. 1978;36:109–116. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amsellem J, Ricci C. Zoomorphology. 1982;100:89–105. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ricci C. Hydrobiologia. 1983;104:175–180. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ricci C. Hydrobiologia. 1991;211:147–155. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crompton D W T, Nickol B B, editors. Biology of the Acanthocephala. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ricci C, Melone G, Sotgia C. Hydrobiologia. 1993;255/256:495–511. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li W-H. Molecular Evolution. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hickey D A. Genetics. 1982;101:519–531. doi: 10.1093/genetics/101.3-4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arkhipova I, Meselson M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14473–14477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blackman R, Meselson M. J Mol Biol. 1986;188:499–515. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(86)80001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wright F. Gene. 1990;87:23–29. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mark Welch D B. Dissertation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li W-H. J Mol Evol. 1993;36:96–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02407308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pamilo P, Bianchi N O. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10:271–281. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nei M, Kumar S. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Z, Nielsen R. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:32–43. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Z. Comput Appl Biosci. 1997;13:555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldman N, Yang Z. Mol Biol Evol. 1994;11:725–736. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarich V M, Wilson A C. Science. 1973;179:1144–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4078.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu C-I, Li W-H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1741–1745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.6.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gupta R S. Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12:1063–1073. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Endo T, Ikeo K, Gojobori T. Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13:685–690. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leigh E G., Jr Genetics. 1973;Suppl. 73:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kimura M, Muruyama T. Genetics. 1966;54:1337–1351. doi: 10.1093/genetics/54.6.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kondrashov A S. Genet Res. 1995;66:53–70. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300033139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnson T. Genetics. 1999;151:1621–1631. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sturtevant A. Q Rev Biol. 1937;12:464–467. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blomberg C. J Theor Biol. 1985;115:241–268. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(85)80099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blomberg C. J Theor Biol. 1987;128:87–107. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(87)80033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kirkwood T B L, Rosenberger R F, Galas D J, editors. Accuracy in Molecular Processes: Its Control and Relevance to Living Systems. London: Chapman & Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muller H J. Mutat Res. 1964;1:2–9. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(64)90047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kondrashov A S. Nature (London) 1988;336:435–440. doi: 10.1038/336435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]