Abstract

RIP3 is a member of the RIP kinase family. It is expressed in the embryo and in multiple adult tissues, including most hemopoietic cell lineages. Several studies have implicated RIP3 in the regulation of apoptosis and NF-κB signaling, but whether RIP3 promotes or attenuates activation of the NF-κB family of transcription factors has been controversial. We have generated RIP3-deficient mice by gene targeting and find RIP3 to be dispensable for normal mouse development. RIP3-deficient cells showed normal sensitivity to a variety of apoptotic stimuli and were indistinguishable from wild-type cells in their ability to activate NF-κB signaling in response to the following: human tumor necrosis factor (TNF), which selectively engages mouse TNF receptor 1; cross-linking of the B- or T-cell antigen receptors; peptidoglycan, which activates Toll-like receptor 2; and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which stimulates Toll-like receptor 4. Consistent with these observations, RIP3-deficient mice exhibited normal antibody production after immunization with a T-dependent antigen and normal interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and TNF production after LPS treatment. Thus, we can exclude RIP3 as an essential modulator of NF-κB signaling downstream of several receptor systems.

RIP3 was first identified as a protein able to interact with the serine/threonine kinase RIP and as a protein with an N-terminal kinase domain similar to that found in RIP and the related kinase RIP2 (5, 11, 17, 20). Whereas RIP possesses a C-terminal death domain and RIP2 has a C-terminal caspase activation and recruitment domain, RIP3 has a unique C terminus. Transient expression of RIP3 at high levels in cell lines was found to promote apoptosis (5, 11, 17, 20), an outcome that also can be observed with RIP (15). However, studies of RIP-deficient mice have shown that in a physiological setting RIP is essential for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-induced activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex and is antiapoptotic (1, 6). IKK-mediated phosphorylation of the IκBs promotes their ubiquitination and degradation, which allow the NF-κB transcription factors that IκBs sequester in the cytosol to move into the nucleus (3, 4). Consistent with a role for RIP in activation of NF-κB, RIP is a potent activator of NF-κB-dependent reporter genes in transient-overexpression studies. RIP3, by comparison, is a poor activator of such reporter genes and will even inhibit RIP- or TNF-induced NF-κB activation (5, 11, 17, 20). Nevertheless, RIP3 was isolated recently from a mouse thymus expression library in a screen for proteins that could activate an NF-κB-dependent reporter gene (13).

Mutagenesis experiments have indicated that interactions between RIP and RIP3 are mediated by a RIP homotypic interaction motif located toward the C terminus of RIP3 and between the kinase and death domains of RIP (18). Disruption of either RIP homotypic interaction motif prevented RIP3 from phosphorylating RIP. It also negated the inhibitory effect of RIP3 on RIP- or TNF-induced NF-κB activation. Phosphorylation of RIP by RIP3 was crucial to the inhibitory action of RIP3 because a kinase-dead form of RIP3 failed to block RIP- or TNF-induced NF-κB activation (18). These results suggested that RIP3, similar to the protein A20 (8), might play a role in limiting the NF-κB-dependent gene transcription that occurs in response to TNF engaging TNF receptor 1 (TNFR-1). To determine the importance of RIP3 to signaling in the whole animal, we have generated RIP3-deficient mice by gene targeting. Mice lacking RIP3 were healthy and fertile and showed no signs of deregulated NF-κB signaling downstream of TNFR-1 or Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 (TLR-2 and -4).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of rip3 mutant mice.

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all protocols. A genomic rip3 clone was isolated from a 129/SvJ library (Incyte Genomics) and was used to construct a targeting vector (Fig. 1A) that was electroporated into 129 R1 embryonic stem (ES) cells. Two homologous recombinants (clones 10 A3 and 13 A12) were identified by Southern blotting with probes 5′ and 3′ of genomic sequence present in the targeting vector (Fig. 1A and B). These heterozygous rip3+/− ES cell clones were microinjected into C57BL/6N blastocysts, and chimeric offspring were backcrossed to C57BL/6N mice. Germ line transmission was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis of tail DNA. All mice analyzed in this study were 6 to 14 weeks old, retained the PGK-neo cassette, and were generated from rip3+/− intercrosses (having backcrossed to C57BL/6N mice for 1 to 4 generations).

FIG. 1.

Generation of RIP3-deficient mice. (A) Exons 1 to 3 encoding amino acids 1 to 158 of mouse RIP3 were replaced with a PGK-neo selection cassette flanked by loxP sites. (B) Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA from wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and homozygous (−/−) rip3 mutant mice. NheI-digested DNAs were hybridized to probe A, which binds sequence that is 5′ of the targeting construct (upper panel). The 4.3- and 6.2-kb DNA fragments correspond to the wild-type and mutant rip3 alleles, respectively. XhoI-digested DNAs were hybridized to probe B, which binds sequence that is 3′ of the targeting construct (lower panel). The 6.5- and 4.3-kb DNA fragments correspond to the wild-type and mutant rip3 alleles, respectively. (C) Western blot analysis of RIP3 protein in embryo fibroblasts (MEFs), purified B and T lymphocytes, and bone marrow-derived macrophages from rip3+/+, rip3+/−, and rip3−/− mice. Blots were probed with a rabbit polyclonal antibody that recognizes amino acids 473 to 486 of mouse RIP3 (upper panel) and then with a mouse monoclonal antibody against β-actin (lower panel).

Immunization and ELISA.

Mice from line 13 A12 were immunized at 11 weeks of age with the T-dependent antigen dinitrophenyl (DNP) coupled to ovalbumin (OVA); 10 μg of DNP-OVA in alum was delivered by intraperitoneal injection. A booster was given 10 days later, and serum samples were collected 21 days after the initial immunization. DNP-specific immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with trinitrophenyl conjugated to bovine serum albumin (TNP-bovine serum albumin; Biosearch Technologies) as a capture agent and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rat anti-mouse IgG1 (BD Biosciences) as the revealing reagent. Absolute levels of anti-DNP IgG1 were determined by using 107.3 IgG1 mouse anti-TNP (BD Biosciences) as a standard.

LPS treatment and cytokine measurements.

Mice from line 13 A12 were backcrossed to a C57BL/6N genetic background for 4 generations, and females aged 9 weeks were given 30 μg of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from Escherichia coli 055:B5 (Sigma) by intraperitoneal injection. Serum was collected after 2 h. Absolute levels of interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and TNF were determined by using mouse Quantikine ELISA kits (R&D Systems).

Immunofluorescence staining, cell sorting, and flow cytometry.

Single-cell suspensions prepared from thymus, spleen, bone marrow, and lymph nodes were surface stained with monoclonal antibodies conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and R-phycoerythrin (PE). Viable cells not stained by propidium iodide were analyzed in a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). The monoclonal antibodies used were H129.19 anti-CD4, 53-6.7 anti-CD8, 145-2C11 anti-CD3ɛ, M1/70 anti-Mac-1, RA3-6B2 anti-B220, R6-60.2 anti-IgM, 11-26c.2a anti-IgD, RB6-8C5 anti-Gr-1, DX5 anti-CD49b, and TER-119 anti-erythroid cells (BD Biosciences). For proliferation assays, B and T cells were negatively sorted from spleen and lymph nodes, respectively. Viable, small cells not stained with a cocktail of antibodies specific for macrophages, granulocytes, erythroid cells (anti-Mac-1, TER-119, and Gr-1), and either B (anti-B220, IgM, and IgD) or T cells (anti-CD3, CD4, and CD8) were sorted in a MoFlo (Cytomation). Apoptosis of thymocytes treated with 2 ng of phorbol myristate acetate (Sigma)/ml, 1 μg of ionomycin (Sigma)/ml, 1 μM dexamethasone (Sigma), 10 ng of recombinant human TNF (Genentech) ± 20 μg of cycloheximide per ml, or 100 ng of Flag-tagged human FasL (Alexis)/ml cross-linked with 1 μg of M2 anti-FLAG antibodies (Sigma)/ml was assayed by staining cells with propidium iodide and FITC-conjugated annexin V (BD Biosciences).

Proliferation assays.

Purified B and T lymphocytes (typically > 95% pure as judged by flow cytometric analysis of cells stained with anti-B220 or anti-CD4 and CD8 antibodies) were cultured in the high-glucose version of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 250 μM l-asparagine, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10% fetal calf serum. T cells (105 cells/ml, starting concentration) were stimulated with plate-bound 145-2C11 anti-CD3ɛ and 37.51 anti-CD28 antibodies (10 μg of each antibody/ml in the coating solution; BD Biosciences). B cells (3 × 105 cells/ml, starting concentration) were stimulated with 20 μg of F(ab′)2 goat anti-mouse IgM (Jackson ImmunoResearch)/ml, or 20 μg of LPS from Salmonella enterica serovar Abortus Equi (Sigma)/ml. One-hundred-microliter cultures were pulsed for 6 h with 0.5 μCi of [methyl-3H]thymidine (Amersham).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

Nuclear extracts were prepared from lymph node cells essentially as described earlier (7). Two micrograms of protein extract and 1 μg of poly(dI-dC) (Amersham) were incubated at 4°C for 10 min in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 0.1% NP-40, and 1 mM dithiothreitol. A 32P-labeled probe containing the κB3 site from the murine rel promoter was added, and complexes were allowed to form at room temperature for 30 min. The products were resolved in 6% polyacrylamide DNA retardation gels (Invitrogen).

Embryo fibroblasts and macrophages.

Fibroblasts derived from embryos at 13.5 to 14.5 days postcoitum by trypsinization were cultured for 2 to 4 passages on gelatin-coated plates in the high-glucose version of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Macrophages were derived from bone marrow cells cultured for 4 to 6 days in the high-glucose version of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 250 μM l-asparagine, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% fetal calf serum, and 25 ng of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (R&D Systems)/ml. Nonadherent cells were washed away, and the adherent macrophages were stimulated with 20 ng of recombinant human TNF/ml, 10 μg of peptidoglycan from Staphylococcus aureus (Sigma)/ml, or 1 μg of LPS from S. enterica serovar Abortus Equi (Sigma)/ml.

Western blotting.

Cell lysates were prepared in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 135 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate, and 0.1 mM β-glycerophosphate supplemented with a complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Proteins were resolved in 4 to 20% gradient Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen) and were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen). Blots were probed with the following antibodies: rabbit anti-mouse RIP3 (MoBiTec), AC-15 anti-β-actin (Abcam), rabbit anti-IκBα (Cell Signaling), and rabbit anti-phospho-IκBα (Ser32) (Cell Signaling).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Targeted disruption of rip3.

RIP3-deficient mice were generated with a targeting vector designed to remove exons 1 to 3, which encode amino acids 1 to 158 (Fig. 1A). We obtained two independent ES cell clones (10 A3 and 13 A12) with a disrupted rip3 allele, and these were injected into blastocysts to generate chimeric mice. Chimeras were crossed to C57BL/6N mice, and their heterozygous rip3+/− offspring were intercrossed to yield homozgyous rip3−/− mice at the expected Mendelian frequency. ES cells and mice were genotyped by PCR (data not shown) and Southern blotting (Fig. 1B). We confirmed that no RIP3 protein was made in the rip3−/− mice by using a polyclonal antibody against amino acids 473 to 486 in Western blot analyses of embryo fibroblasts, bone marrow-derived macrophages, purified B and T lymphocytes, and thymocytes (Fig. 1C and data not shown). The phenotypes of both lines of rip3 mutant mice were the same: animals appeared healthy and were fertile, and histological analysis did not reveal abnormalities in any of the major organs (data not shown).

RIP3 is dispensable for macrophage, lymphocyte, and natural killer cell development.

Both myeloid and lymphoid cell lineages express RIP3 (Fig. 1C and data not shown), so we examined the development of these cell populations in rip3−/− mice. Thymus, spleen, lymph node, and bone marrow cellularities were comparable between rip3−/− mice and their wild-type littermates (data not shown). Flow cytometric analysis of cells stained with antibodies to CD4 and CD8 revealed no difference in the frequency of CD4+8+, CD4+8−, and CD4−8+ cells in thymus, spleen, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood, suggesting that T-cell development can occur normally in the absence of RIP3 (Fig. 2A and B and data not shown). The proportion of cells expressing B220 and IgM in the bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood also was not affected by loss of RIP3, suggesting that RIP3 is not essential for B-cell development (Fig. 2C and D and data not shown). In addition, rip3−/− mice had normal numbers of CD49b+ natural killer cells, TER119+ erythroid cells, and Mac-1+ Gr-1+ macrophages (Fig. 2C and D and data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and macrophages develop normally in the absence of RIP3. Flow cytometric analysis of cells in the thymus, lymph nodes, bone marrow, and spleen of 8-week-old wild-type (+/+) and RIP3-null (−/−) mice. Numbers indicate the percentage of cells within each quadrant or region. Dot plots are representative of six mice of each genotype.

To determine whether RIP3 is important to B- and T-cell function, we measured rip3−/− lymphocyte proliferation in response to various mitogens in vitro (Fig. 3A and B). By [3H]thymidine incorporation, purified rip3−/− spleen B cells proliferated as well as their wild-type counterparts in response to anti-IgM antibodies, anti-CD40 antibodies, or LPS (Fig. 3A and data not shown). Similarly, purified rip3+/+ and rip3−/− lymph node T cells were indistinguishable in their proliferative response to cross-linking antibodies to CD3 and CD28 (Fig. 3B). To assess B- and T-cell function in vivo, we immunized rip3−/− mice with the T-dependent antigen dinitrophenyl linked to ovalbumin (DNP-OVA). DNP-specific antibodies of the IgG1 isotype were elicited in equivalent quantities in rip3+/+ and rip3−/− mice (Fig. 3D), suggesting that RIP3 is dispensable for normal humoral immunity. Basal levels of IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, and IgA in the serum of rip3−/− mice also were within normal limits (data not shown). Because mice lacking one or more of the NF-κB transcription factors Rel, RelA (also called p65), and NF-κB1 (also called p50) exhibit defects in lymphocyte development, proliferation, and antibody production (2, 7, 12, 14, 21), our findings suggest that RIP3 is not required to transduce signals for NF-κB activation downstream of the B- and T-cell receptors. Consistent with this notion, rip3+/+ and rip3−/− lymph node T cells stimulated with cross-linking antibodies to CD3 and CD28 exhibited equivalent NF-κB DNA binding activity in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (Fig. 3C). Both rip3+/+ and rip3−/− cells contained two nuclear NF-κB complexes (C1 and C2) able to bind to the κB3 site from the murine rel promoter, and as in previous studies (7, 10), the slower-migrating C1 complex was increased following mitogenic stimulation.

FIG.3.

RIP3 is not essential for lymphocyte proliferation or antibody production. (A) Purified spleen B cells from wild-type (+/+; filled circles) and RIP3-deficient (−/−; open circles) mice were stimulated with 20 μg of anti-IgM antibodies (left panel)/ml or with 20 μg of LPS (right panel)/ml. Proliferation was measured by [3H]thymidine uptake for 6 h on the days indicated. Data points represent the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate wells. Results are representative of two independent experiments. (B) Proliferation of purified lymph node T cells stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3ɛ and anti-CD28 antibodies. Data points represent the mean ± standard deviation for three mice of each genotype. (C) NF-κB DNA binding activity in nuclear extracts prepared from lymph node T cells stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3ɛ and anti-CD28 antibodies. C1 and C2 are complexes of NF-κB and a DNA probe containing the κB3 binding site from the murine rel promoter. The open arrowhead indicates nonspecific binding to the κB3 probe, and the filled arrowhead indicates free κB3 probe. (D) DNP-specific IgG1 antibodies in the serum of rip3+/+ and rip3−/− mice after immunization with the T-dependent antigen DNP-OVA were quantified by ELISA. Each circle represents one mouse. Horizontal lines indicate the mean antibody level.

Normal apoptosis of rip3−/− cells.

Transient overexpression of RIP3 induces apoptosis in cell lines (5, 11, 17, 20), so we investigated whether RIP3 might regulate cell survival by measuring rip3−/− thymocyte apoptosis in response to different stimuli. rip3−/− thymocytes underwent spontaneous apoptosis in culture at the same rate as rip3+/+ thymocytes (Fig. 4A), and they did not exhibit altered sensitivity to the phorbol ester phorbol myristate acetate, the calcium ionophore ionomycin, or the glucocorticoid dexamethasone, or Fas ligand (FasL) (Fig. 4B). Like wild-type thymocytes, rip3−/− thymocytes were not killed by recombinant human TNF, which specifically engages mouse TNFR-1 (9). This last result, together with the general good health of rip3−/− mice, suggests that RIP3 is not like the cytoplasmic zinc finger protein A20 and does not play a critical role in limiting NF-κB signaling downstream of TNFR-1. In contrast to rip3−/− mice, A20-deficient mice die soon after birth from inflammatory disease, and their cells, including thymocytes, are hypersensitive to TNF-induced apoptosis (8).

FIG. 4.

Normal apoptosis and NF-κB signaling in cells lacking RIP3. (A and B) Thymocytes from wild-type (+/+; filled bars) and RIP3-deficient (−/−; open bars) mice were cultured for 3 days in medium alone (A) or were treated for 1 day with 2 ng of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)/ml, 1 μg of ionomycin (Iono)/ml, 1 μM dexamethasone (Dex), 10 ng of human TNF ± 20 μg of cycloheximide (CHX) per ml, or 100 ng of Flag-tagged human FasL/ml cross-linked with M2 anti-FLAG antibodies (B). Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry after staining with FITC-conjugated annexin V and propidium iodide. The percentage of viable cells not stained by either dye is shown. Data points represent the mean ± standard deviation for three mice of each genotype. (C) Western blot analysis of rip3+/+ and rip3−/− embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) after treatment with 20 ng of human TNF/ml. Blots were probed with antibodies that recognize a phosphorylated form of IκBα (upper panel), all forms of IκBα (middle panel), and β-actin (lower panel). (D) Western blot analysis of bone marrow-derived macrophages from rip3+/+ and rip3−/− mice after treatment with 20 ng of human TNF/ml, 10 μg of peptidoglycan/ml, or 1 μg of LPS/ml. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Normal NF-κB signaling by TNFR-1, TLR-2, and TLR-4 in rip3−/− cells.

To examine the NF-κB signaling pathway downstream of TNFR-1 in rip3−/− cells directly, we determined whether IκBα is phosphorylated and then degraded in rip3−/− embryo fibroblasts and bone marrow-derived macrophages treated with human TNF. Western blot analysis with antibodies to IκBα revealed transient phosphorylation of IκBα after 5 min of TNF treatment, and this was followed by a reduction in the overall level of IκBα both in rip3+/+ and rip3−/− cells (Fig. 4C and D). IκBα is itself induced by NF-κB (16), and accordingly, IκBα in rip3+/+ and rip3−/− cells had returned to basal levels after 60 min of stimulation with TNF (Fig. 4C). In the case of A20-null cells, IκBα protein is induced but persistent IKK activity appears to prevent its accumulation (8). Thus, consistent with the healthy phenotype of rip3−/− mice, RIP3 is dispensable for TNF-induced activation of NF-κB and for later switching off of NF-κB-dependent gene transcription. Absence of a phenotype in rip3−/− cells when RIP3 inhibited TNF- and RIP-induced NF-κB transcriptional activity in overexpression studies (18) might indicate that RIP3 and another protein(s) have overlapping, redundant roles in negatively regulating TNF-induced NF-κB signaling or that the previously observed inhibitory activity of RIP3 might simply be an artifact of its ectopic expression.

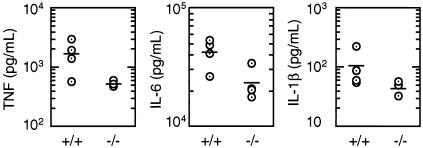

We also looked at the response of rip3−/− macrophages to the gram-negative bacterial cell wall component peptidoglycan and the gram-positive bacterial cell wall component LPS, which activate NF-κB via TLR-2 and TLR-4, respectively (19). Phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκBα in response to these stimuli occurred to a similar extent and with similar kinetics in rip3+/+ and rip3−/− cells (Fig. 4D). Thus, macrophages, in addition to B lymphocytes (Fig. 3A), can respond to LPS without RIP3. Consistent with these findings, rip3−/− mice injected with a sublethal dose of LPS produced amounts of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF comparable to those produced by their wild-type littermates (Fig. 5). Therefore, despite the apparent ability of RIP3 to interact with RIP (17, 18, 20), we find no evidence of a nonredundant role for RIP3 in the regulation of NF-κB signaling by TNFR-1 or other receptors such as the B- and T-cell antigen receptors, TLR-2, and TLR-4.

FIG. 5.

RIP3-deficient mice injected with LPS produce normal amounts of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF. Wild-type (+/+) and RIP3-null (−/−) female mice aged 9 weeks received 30 μg of LPS/ml by intraperitoneal injection, and levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF in the serum after 2 h were determined by ELISA. Each circle represents one mouse. Horizontal lines indicate the mean cytokine level.

Acknowledgments

We thank Luz Orellana, Jessica Kloss, and Meg Fuentes for animal husbandry, Peter Schow and Wendy Tombo for their assistance with flow cytometry, and Peter Wong, Merone Roose-Girma, Willis Su, Lucrece Tom, Khiem Tran, Joel Morales, Marjie Van Hoy, Sanjeev Mariathasan, and Michele Bauer for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Devin, A., A. Cook, Y. Lin, Y. Rodriguez, M. Kelliher, and Z. Liu. 2000. The distinct roles of TRAF2 and RIP in IKK activation by TNF-R1: TRAF2 recruits IKK to TNF-R1 while RIP mediates IKK activation. Immunity 12:419-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doi, T. S., T. Takahashi, O. Taguchi, T. Azuma, and Y. Obata. 1997. NF-κB relA-deficient lymphocytes: normal development of T cells and B cells, impaired production of IgA and IgG1 and reduced proliferative responses. J. Exp. Med. 185:953-961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh, S., M. J. May, and E. B. Kopp. 1998. NF-kappa B and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16:225-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karin, M. 1999. How NF-kappaB is activated: the role of the IkappaB kinase (IKK) complex. Oncogene 18:6867-6874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasof, G. M., J. C. Prosser, D. Liu, M. V. Lorenzi, and B. C. Gomes. 2000. The RIP-like kinase, RIP3, induces apoptosis and NF-kappaB nuclear translocation and localizes to mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 473:285-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelliher, M. A., S. Grimm, Y. Ishida, F. Kuo, B. Z. Stanger, and P. Leder. 1998. The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-κB signal. Immunity 8:297-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Köntgen, F., R. J. Grumont, A. Strasser, D. Metcalf, R. Li, D. Tarlinton, and S. Gerondakis. 1995. Mice lacking the c-rel proto-oncogene exhibit defects in lymphocyte proliferation, humoral immunity, and interleukin-2 expression. Genes Dev. 9:1965-1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee, E. G., D. L. Boone, S. Chai, S. L. Libby, M. Chien, J. P. Lodolce, and A. Ma. 2000. Failure to regulate TNF-induced NF-κB and cell death responses in A20-deficient mice. Science 289:2350-2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis, M., L. A. Tartaglia, A. Lee, G. L. Bennett, G. C. Rice, G. H. Wong, E. Y. Chen, and D. V. Goeddel. 1991. Cloning and expression of cDNAs for two distinct murine tumor necrosis factor receptors demonstrate one receptor is species specific. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:2830-2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newton, K., and V. M. Dixit. 2003. Mice lacking the CARD of CARMA1 exhibit defective B lymphocyte development and impaired proliferation of their B and T lymphocytes. Curr. Biol. 13:1247-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pazdernik, N. J., D. B. Donner, M. G. Goebl, and M. A. Harrington. 1999. Mouse receptor interacting protein 3 does not contain a caspase-recruiting or a death domain but induces apoptosis and activates NF-κB. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:6500-6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pohl, T., R. Gugasyan, R. J. Grumont, A. Strasser, D. Metcalf, D. Tarlinton, W. Sha, D. Baltimore, and S. Gerondakis. 2002. The combined absence of NF-kappa B1 and c-Rel reveals that overlapping roles for these transcription factors in the B cell lineage are restricted to the activation and function of mature cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:4514-4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pomerantz, J. L., E. M. Denny, and D. Baltimore. 2002. CARD11 mediates factor-specific activation of NF-kappaB by the T cell receptor complex. EMBO J. 21:5184-5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snapper, C. M., P. Zelazowski, F. R. Rosas, M. R. Kehry, M. Tian, D. Baltimore, and W. C. Sha. 1996. B cells from P50/NF-κ-B knockout mice have selective defects in proliferation, differentiation, germ-line C-H transcription, and Ig class switching. J. Immunol. 156:183-191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanger, B. Z., P. Leder, T.-H. Lee, E. Kim, and B. Seed. 1995. RIP: a novel protein containing a death domain that interacts with Fas/APO-1 (CD95) in yeast and causes cell death. Cell 81:513-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun, S. C., P. A. Ganchi, D. W. Ballard, and W. C. Greene. 1993. NF-κ B controls expression of inhibitor I κ B α: evidence for an inducible autoregulatory pathway. Science 259:1912-1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun, X., J. Lee, T. Navas, D. T. Baldwin, T. A. Stewart, and V. M. Dixit. 1999. RIP3, a novel apoptosis-inducing kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:16871-16875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun, X., J. Yin, M. A. Starovasnik, W. J. Fairbrother, and V. M. Dixit. 2002. Identification of a novel homotypic interaction motif required for the phosphorylation of receptor-interacting protein (RIP) by RIP3. J. Biol. Chem. 277:9505-9511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeuchi, O., K. Hoshino, T. Kawai, H. Sanjo, H. Takada, T. Ogawa, K. Takeda, and S. Akira. 1999. Differential roles of TLR2 and TLR4 in recognition of gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial cell wall components. Immunity 11:443-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu, P. W., B. C. Huang, M. Shen, J. Quast, E. Chan, X. Xu, G. P. Nolan, D. G. Payan, and Y. Luo. 1999. Identification of RIP3, a RIP-like kinase that activates apoptosis and NFkappaB. Curr. Biol. 9:539-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng, Y., M. Vig, J. Lyons, L. Van Parijs, and A. A. Beg. 2003. Combined deficiency of p50 and cRel in CD4+ T cells reveals an essential requirement for nuclear factor kappaB in regulating mature T cell survival and in vivo function. J. Exp. Med. 197:861-874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]