Abstract

Background

Bilateral traumatic femoral neck fractures are uncommon in children. The most commonly reported complications are nonunion, avascular necrosis of the femoral head, and chondrolysis. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) associated with nonunion after percutaneous partially threaded cancellous screw (PTCS) fixation of the fracture is an unreported complication.

Case Description

We describe a 10-year-old boy who had bilateral femoral neck fractures secondary to a fall from a height. The patient was treated with percutaneous PTCS fixation on both sides and achieved union on the right side in 3 months, however, a nonunion and SCFE developed on the left side 5 months after the initial surgery. Management of the nonunion and SCFE with PTCS and nonvascularized fibula graft led to union. Eighteen months after the initial injury, the patient achieved a pain and limp-free gait.

Literature Review

A literature review shows avascular necrosis, posttraumatic coxa vara, premature physeal closure, nonunion, chondrolysis, infection, and implant failure as complications of operative management of femoral neck fractures. SCFE has not been previously reported.

Purposes and Clinical Relevance

This case highlights the need for close followup of adolescent patients with PTCS fixation for femoral neck fractures.

Introduction

Fractures of the femoral neck are always a challenge for orthopaedic surgeons, not only because treatment needs expertise, but also because of complications during the early and late postoperative periods. Although femoral neck fractures are common in adults, they are rare in children, representing less than 1% of all pediatric fractures [3]. Traumatic bilateral femoral neck fracture is even rarer in children, with only a few cases having been reported [10, 13, 21]. Most of the nontraumatic bilateral femoral neck fractures have been reported in adults or in patients with metabolic bone diseases or malignant diseases of other organs or postseizure [2, 5, 6, 18]. Traumatic femoral neck fractures in children are associated with high rates of complications [1, 20] owing to the typically high-velocity nature of the fractures, the unique vascularity of the proximal femur, open physes, and in developing countries a frequently delayed presentation to healthcare facilities. Complications include avascular necrosis of the femoral head, nonunion, posttraumatic coxa vara, growth arrest, infection, and chondrolysis [4].

We report a case of bilateral traumatic femoral neck fractures treated surgically and an as-yet-unreported complication of slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) after percutaneous partially threaded cancellous screw (PTCS) fixation.

Case Report

A 10-year-old boy was brought to the emergency room after a fall from a height. Radiographs showed bilateral femoral neck fractures (Fig. 1). He was average built with a height of 155 cm and weight of 50 kg. The fractures were Delbet Type 2 on the left side and Type 3 on the right side [7]. The Delbet classification of pediatric femoral neck fracture was popularized by Colonna [7] and it classifies the fracture into four types based on the location of the fracture line. Type 1 is a transphyseal fracture, Type 2 is transcervical, Type 3 is cervicotrochanteric or basicervical, and Type 4 is intertrochanteric. He was operated on within 48 hours. Closed reduction was attempted on the left side under an image intensifier using the Whitman method as described by Herring [11]. After failure of three attempts using the Whitman method, reduction was obtained by the minimally traumatic reduction technique of Su et al. [19], and the fracture was fixed with two 6.5-mm PTCSs passed up to the physis. On the right side, acceptable reduction was obtained by the Whitman technique and a percutaneous fracture fixation was performed with two PTCSs (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

A radiograph shows bilateral femoral neck fractures in a 10-year-old boy.

Fig. 2.

An immediate postoperative radiograph shows the anatomic reduction and percutaneous PTCS fixation of the femoral neck fractures on both sides.

Postoperatively the patient was treated with spica immobilization for 6 weeks. While wearing the spica cast the patient did ankle pumps and static quadriceps exercises 100 times a day in five sets of 20 each under supervision. After removal of the cast, the patient was maintained on bedrest at home but hip and knee ROM exercises were begun under supervision of a physiotherapist, being performed in five sets of 20 each for the next 6 weeks. Because he had bilateral fractures, we planned to delay weightbearing until there was evidence of radiographic union of the fractures. Radiographs 12 weeks postoperatively showed union on the right side and maintained fixation on the left side without union (Fig. 3). The patient was advised to use crutches for walking, with weightbearing allowed only on the right side, however, the patient started weightbearing on the opposite side as well. Twenty weeks after surgery, the patient returned with left hip pain. We observed a slip of the left proximal femoral epiphysis on radiographs (Fig. 4). Revision surgery was performed. The reduction of the femoral neck fracture was held with threaded K-wires and the screws were removed. The SCFE was reduced and the reduction was maintained by advancing the threaded K-wires up to the subchondral bone under an image intensifier. One PTCS was passed up to the subchondral bone. A 10-cm ipsilateral nonvascularized fibula graft was inserted in the center up to the physis as described by Nagi et al. [17] (Fig. 5). A hip spica cast was applied for 6 weeks and the child was kept nonweightbearing until radiographic fracture union was observed 16 weeks after the second surgery. Similar to the initial surgery, while wearing the spica cast the patient performed ankle pumps and static quadriceps exercises, and after the cast was removed, he began knee and hip ROM exercises under the supervision of a physiotherapist. Crutch walking with weightbearing was allowed on the right side after removal of the spica cast, and partial followed by full weightbearing was allowed after union of the left side was observed on radiographs. At 18 months followup after the second surgery the patient was pain free and had no limp. He was able to walk unassisted, squat (Fig. 6A), sit cross-legged, and jog comfortably. Radiographs obtained at 18 months followup showed a united fracture with a well-incorporated fibular graft and with no signs of avascular necrosis (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 3A–B.

(A) AP and (B) frog leg lateral radiographs obtained 3 months postoperatively show union on the right side and lack of union but maintained reduction on the left side. The arrow shows Klein’s line.

Fig. 4.

A radiograph obtained 5 months postoperatively shows SCFE as evidenced by the Trethowan’s sign [11, 12], ie, Klein’s line (arrow) intersecting only a small part or no part of the proximal femoral epiphysis.

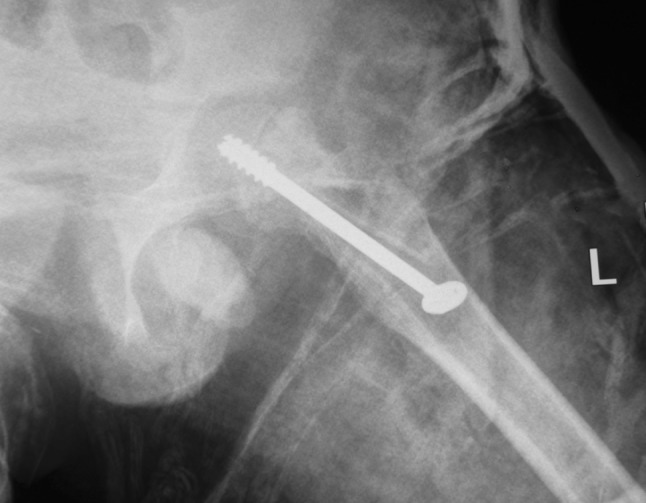

Fig. 5.

An immediate postoperative radiograph shows the fracture on the left side after revision surgery with PTCS and ipsilateral fibula graft.

Fig. 6A-B.

(A) A clinical photograph taken at the 18-month followup shows the patient is able to squat. (B) A radiograph obtained at that same followup shows a united fracture and well-incorporated fibula graft.

Discussion

Bilateral traumatic femoral neck fractures are rare injuries in children, with only a few cases having been reported in the literature, and are associated with high complication rates, eventually leading to poor outcomes [10, 13, 21]. Togrul et al. [20] reported only one case of traumatic bilateral femoral neck fractures in their retrospective study of 103 femoral neck fractures over 16 years. Traumatic femoral neck fractures are typically high-energy injuries and 85% of children have other associated injuries, commonly pelvic and head injuries [15]. These other serious injuries may lead to missed hip fractures and substantial delay in fixation of these fractures. Our patient had no associated injury and he presented within 36 hours of injury. When considered individually, the fracture patterns on the two sides were not exceptional. However, during reduction of the fracture of the left side for percutaneous PTCS fixation on the fracture table, we were unable to reduce the Delbet Type 2 fracture by the Whitman method which is a commonly used method for reduction of femoral neck fractures in adults and children at our institution. The Whitman method of closed reduction, as described by Herring [11], consists of positioning the patient on the fracture table and placing the unaffected extremity in abduction to fix the pelvis. Next, gentle in-line traction is applied on the affected limb followed by progressive abduction of the limb and then the limb is internally rotated by 20° to 30° to reduce the fracture. Once reduction is achieved, the extremity is slowly adducted to allow for screw placement. The Whitman method might have failed in our patient owing to ineffective traction on the fracture table as the pelvis probably was not adequately stabilized because of the patient’s bilateral injuries, and abduction might have occurred at the fracture site on the right side instead of occurring on the left side or owing to impaction of the distal fragment into the proximal fragment. Once the left fracture was fixed, the right fracture could be reduced easily by the Whitman method. The pattern of fracture on the right side also was more favorable for reduction by the Whitman method. In case of bilateral fractures of the femoral neck one can consider use of the minimally traumatic reduction technique described by Su et al. [19], if gentle attempts of reduction by the conventional methods fail to achieve acceptable reduction. This minimally traumatic technique is performed under an image intensifier and is done with the patient in the supine position. The femoral pulse is palpated and a Steinmann pin is placed percutaneously from anterior to posterior approximately 1.5 cm lateral to the femoral pulse into the middle ½ to 2/3 of the femoral head. The pin should be located 1 cm inferior to the subchondral bone. The tip of the pin is directed slightly lateral and is confirmed under an image intensifier. This pin now functions as a joystick and is used to stabilize the proximal fragment (head of femur) while the distal fragment is manipulated to reduce the fracture.

The most common complication in pediatric femoral neck fractures is avascular necrosis of the femoral head [4, 11]. Fracture type and age at the time of injury are reportedly the best predictors of avascular necrosis [16]. The probability of AVN developing is maximal with Delbet Type 1 fractures and least with Type 4 fractures. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head may result in patients with a fracture of the femoral neck with kinking of blood vessels, vessel wall laceration, or a tamponade effect of intracapsular bleeding of the retinacular vessels. Other complications include posttraumatic coxa vara which tends to occur in 30% of cases, nonunion in 1.6% to 10% [8, 9, 20], infection and chondrolysis in less than 1% [4]. Premature physeal closure is another common complication and its incidence varies from 5% to 65%. Considering that the distal femur is the growing end of the femur and the proximal femur contributes only 15% of overall limb length, the overall impact of premature closure of the physis depends on the age when closure occurs [4]. Although premature closure at a young age leads to substantial shortening of the limb, premature closure in adolescents may lead to a minor degree of shortening, which may be managed with a shoe lift. We found no reports in the English literature of SCFE as a complication of screw fixation of a femoral neck fracture.

SCFE is seen more commonly in boys than in girls and the left side is more commonly affected than the right [14]. In our case, the patient was a boy of average build with bilateral traumatic femoral neck fractures treated initially with percutaneous PTCS fixation on both sides and later, SCFE developed on the left side. The exact cause of the slipped epiphysis was not known. The causes of the SCFE might have been the precarious blood supply of the growing epiphysis, nonunion at the fracture site, or the location of the screw tip just below the physis thereby possibly weakening the interface between the epiphysis and the femoral neck and thinning the perichondral ring [11]. In addition to these possible reasons, the patient started weightbearing against our instructions and it might have resulted in abnormal shear stresses at the physis and therefore, development of the slipped epiphysis.

Treatment of bilateral fractures of the femoral neck may pose a challenge in that a satisfactory reduction might not be attained. In such cases, the technique of Su et al. may be helpful. A rare complication like SCFE might occur after PTCS fixation of femoral neck fractures and close followup of the patients is needed.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient’s parents for providing us with informed written consent for publication of this case report.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no commercial associations that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the reporting of this case report, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Azam MQ, Iraqi AA, Sherwani M, Abbas M, Alam A, Sabir AB, Asif N. Delayed fixation of displaced type II and III pediatric femoral neck fractures. Indian J Orthop. 2009;43:253–258. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.53455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanco JS, Dahir G, McCrystal K. Bilateral femoral neck fractures secondary to hypocalcemic seizures in a skeletally immature patient. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 1999;28:187–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasier RD, Hughes LO. Fractures and traumatic dislocations of the hip in children. In: Beaty JH, Kasser JR, editors. Rockwood and Wilkins’ Fractures in Children. 6. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. pp. 861–891. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boardman MJ, Herman MJ, Buck B, Pizzutillo PD. Hip fractures in children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:162–173. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200903000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chadha M, Balain B, Maini L, Dhal A. Spontaneous bilateral displaced femoral neck fractures in nutritional osteomalacia: a case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72:94–96. doi: 10.1080/000164701753606770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CE, Kao CL, Wang CJ. Bilateral pathological femoral neck fractures secondary to ectopic parathyroid adenoma. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1998;118:164–166. doi: 10.1007/s004020050339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colonna PC. Fracture of the neck of the femur in childhood: a report of six cases. Ann Surg. 1928;88:902–907. doi: 10.1097/00000658-192811000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flynn JM, Wong KL, Yeh GL, Meyer JS, Davidson RS. Displaced fractures of the hip in children: management by early operation and immobilisation in hip spica cast. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:108–112. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B1.11972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forlin E, Guille JT, Kumar SJ, Rhee KJ. Complications associated with fracture of the neck of the femur in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12:503–509. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199207000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilban HM, Mirdad TM, Jenyo M. Simultaneous post traumatic bilateral cervico-trochanteric femoral neck fractures in a child: a case report. West Afr J Med. 2005;24:348–349. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v24i4.28235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herring JA. Tachdjian’s Pediatric Orthopaedics. 4. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein A, Joplin RJ, Reidy JA, Hanelin J. Roentgenographic features of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1951;66:361–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar P, Singh GK, Singh MP. Traumatic simultaneous bilateral fractures of femoral neck in children: mechanism of injury. J Orthop. 2006;3:e5. Available at: http://www.jortho.org/2006/3/3/e5/index.htm. Accessed June 14, 2012.

- 14.Loder RT. The demographics of slipped capital femoral epiphysis: an international multicenter study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;322:8–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirdad T. Fractures of the neck of femur in children: an experience at the Aseer Central Hospital, Abha. Saudi Arabia. Injury. 2002;33:823–827. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(02)00013-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moon ES, Mehlman CT. Risk factors for avascular necrosis after femoral neck fractures in children: 25 Cincinnati cases and meta-analysis of 360 cases. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:323–329. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200605000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagi ON, Dhillon MS, Gill SS. Fibular osteosynthesis in delayed type II and type III femoral fractures in children. J Orthop Trauma. 1992;6:306–313. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schröder J, Marti RK. Simultaneous bilateral femoral neck fractures: case report. Swiss Surg. 2001;7:222–224. doi: 10.1024/1023-9332.7.5.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su Y, Chen W, Zhang Q, Li B, Li Z, Guo M, Pan J, Zhang Y. An irreducible variant of femoral neck fracture: a minimally traumatic reduction technique. Injury. 2011;42:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Togrul E, Bayram H, Gulsen M, Kalaci A, Ozbarlas S. Fractures of the femoral neck in children: long-term follow-up in 62 hip fractures. Injury. 2005;36:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Upadhyay A, Maini L, Batra S, Mishra P, Jain P. Simultaneous bilateral fractures of femoral neck in children: mechanism of injury. Injury. 2004;35:1073–1075. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(03)00190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]