Abstract

Background

Premature bone loss after childhood chemotherapy may be underestimated in patients with bone sarcoma. Methotrexate (MTX), a standard agent in osteosarcoma protocols, reportedly reduces bone mineral density (BMD). The literature, however, has reported cases of BMD reduction in patients with Ewing's sarcoma treated without MTX. Thus, it is unclear whether osteoporosis after chemotherapy relates to MTX or to other factors.

Questions/purposes

We therefore asked whether (1) young patients with a bone sarcoma had BMD reduction, (2) patients treated with MTX had lower BMD, and (3) other factors (eg, lactose intolerance or vitamin D deficiency) posed additional risks for low BMD.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 43 patients with malignancies who had dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) (lumbar, femoral); 18 with Ewing's sarcoma (mean age, 26 ± 8 years), and 25 with an osteosarcoma (mean age, 27 ± 10 years). The mean time since diagnosis was 8 ± 4 years in the group with Ewing’s sarcoma and 7 ± 5 years in the group with osteosarcoma. At last followup we determined BMD (computing z-scores), fracture rate, and lifestyle, and performed serum analysis.

Results

BMD reduction was present in 58% of patients (37% had a z-score between −1 and −2 SD, 21% had a z-score less than −2 SD) in at least one measured site. Seven of the 43 patients (16%) had nontrauma or tumor-associated fractures after chemotherapy. Findings were similar in the Ewing and osteosarcoma subgroups. We found vitamin D deficiency in 38 patients (88%) and borderline elevated bone metabolism; lactose intolerance was present in 16 patients (37%).

Conclusion

Doctors should be aware of the possibility of major bone loss after chemotherapy with a risk of pathologic fracture. Vitamin D deficiency, calcium malnutrition, and lactose intolerance may potentiate the negative effects of chemotherapy, and should be considered in long-term patient management.

Level of Evidence

Level II, prognostic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

With an estimated incidence of four to five cases per million, osteosarcoma is the most common, nonhemopoietic primary malignant bone tumor, developing most frequently in the second decade of life, with approximately 60% of patients being younger than 25 years [19]. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) and Ewing's sarcoma are the second most common sarcomatous tumors of bone and soft tissue in young patients, with a peak age incidence in the second decade during maximal bone growth [19]. Both tumors affect the long bones of the appendicular skeleton and occur with occult metastases at the time of diagnosis in as much as 90% of cases [3]. Chemotherapy, following standardized study protocols [3, 4, 6, 7, 15, 21, 31], and potential radiotherapy (Ewing's sarcoma) in addition to wide resection have been seen to increase patients' survival [19]. Although the 5-year survival rate for patients with nonmetastasized Ewing's sarcoma has been less than 10% with resection only (with or without radiotherapy) [3], it has reached 50% to 75% with additional chemotherapeutic treatment [3]. A similar increase in survival has been reported for patients with osteosarcoma, for whom the 5-year survival increased from 15% to 50% to 70% [3].

Although chemotherapy is now an essential and powerful part of sarcoma treatment, it also has created a generation of young childhood sarcoma survivors who now are facing long-term effects of early cancer treatment. These patients reportedly have lower peak bone mass with consequently lower bone mineral density (BMD) later in life, followed by premature osteopenia and/or osteoporosis, and a higher risk of osteoporotic fractures [23, 34, 40, 41].

High-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX), a standard agent in the therapy protocols for osteosarcoma, has long been suspected as one of the main triggers of negative long-term effects on bone metabolism and BMD. MTX osteopathy was described in eight of 87 patients with osteosarcoma with at least three of four radiographic abnormalities including osteopenia, dense zones of provisional calcification, insufficiency fractures, and involvement of multiple bones [8]. Among 48 long-term survivors who had DEXA, 10 had osteoporosis, 21 had osteopenia, and 18 had fractures after chemotherapy [17]. However, Ruza et al. questioned MTX as one of the most suspect chemotherapeutics causing premature bone loss because the BMD of patients with Ewing’s sarcoma treated without MTX was reportedly decreased [33]. Thus, it is unclear whether MTX is one of the main triggers of bone loss after chemotherapy or if other factors also play an important role.

We therefore asked whether (1) young patients with bone sarcomas had BMD reduction, (2) patients treated with MTX had lower BMD, and (3) other factors (eg, lactose intolerance or vitamin D deficiency) posed additional risks for low BMD.

Patients and Methods

To evaluate BMD and laboratory alterations in young survivors of bone sarcomas and perform a two-group comparison of patients with Ewing's sarcoma and osteosarcoma, we queried our departmental database (established in 1998). We identified 103 patients treated between 1998 and 2009, and excluded 26 patients who were older than 50 years at the time of the study to minimize the possible influences of menopausal or senile BMD reduction, assumed to arise earliest at approximately this age [14]. This left 77 patients (38 with Ewing’s sarcoma and 39 with osteosarcomas) who had completed chemotherapy and were younger than 50 years at the time of the investigation. Using either the telephone and/or letters, we invited these 77 patients to participate in our study, including densitometry, laboratory examination, and a lifestyle questionnaire. Fifteen patients were lost to followup (five from other countries) and 13 declined participation. These exclusions left 49 patients (64%) who agreed to participate: 43 at our institution and six at an outside hospital. We excluded the six patients from an outside hospital to eliminate technical differences in DEXA scans and laboratory evaluations. Therefore, the 43 patients with densitometry and laboratory studies at our institution represented the final study collective (Table 1), including 18 patients with Ewing's sarcoma (male-to-female ratio, 10:8) with a mean age of 26 ± 8 years (range, 12–44 years) and 25 patients with an osteosarcoma (male-to-female ratio, 16:9) with a mean age of 27 ± 10 years (range, 7–49 years). The tumors affected a solitary site and were located in the lower limbs in 34 patients, in the upper limbs in four, and in other sites than the extremities in five; one patient with Ewing’s sarcoma had multiple lesions. Metastases in the lungs were found in three patients with Ewing's sarcoma and three with osteosarcoma at the time of diagnosis. The mean followup was 8 ± 4 years (range, 3–18 years) in the group with Ewing’s sarcoma and 7 ± 5 years (range, 1–17 years) in the group with osteosarcoma. The local ethics committee approved the study protocol, and all patients gave written informed consent to participate in the study.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Ewing’s sarcoma (n = 18) | Osteosarcoma (n = 25) | Total (n = 43) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male: female | 10:8 | 16:9 | 26:17 |

| Mean age at diagnosis (range) (years) | 18 ± 9 (3-38) | 20 ± 11 (6–45) | 19 ± 11 (3–45) |

| Mean age at followup (range) (years) | 26 ± 8 (12–44) | 27 ± 10 (7–49) | 27 ± 9 (7–49) |

| Mean time between diagnoses and followup (years) | 8 ± 4 | 7 ± 5 | 7 ± 5 |

| Mean height (range) (cm) | 169 ± 12 (130–191) | 172 ± 14 (123–195) | 171 ± 14 (123–195) |

| Mean weight (range) (kg) | 61 ± 16 (25–95) | 67 ± 19 (26–131) | 64 ± 18 (25–131) |

| Mean BMI (range) (kg/m2) | 21 ± 4 (15–29) | 22 ± 6 (16–45) | 22 ± 5 (15–45) |

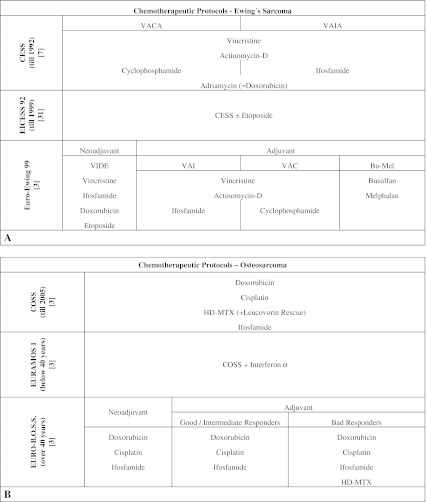

All 43 patients had received chemotherapy according to the treatment protocols (Fig. 1) active at the time of diagnosis, in addition to a wide resection, except one patient with Ewing's sarcoma and one with osteosarcoma who had inoperable tumors. Eight patients, six with Ewing's sarcoma and two with osteosarcomas, also received local radiotherapy: two because of inoperability and six because of anatomically problematic wide resection and partially bad response to chemotherapy.

Fig. 1A–B.

The chemotherapeutic treatment guidelines for Ewing's sarcoma and osteosarcoma according to study proven protocols are shown. (A) The graph shows the chemotherapeutic protocols and major chemotherapeutic agents used for treatment of Ewing's sarcoma [3, 7, 15, 31] and (B) osteosarcoma [3, 6, 15, 21].

To gain information regarding patients' lifestyles, family history, other bone-affecting diseases, and intake of osteoreductive medication, we interviewed them according to a specially adapted questionnaire originally described by Obermayer-Pietsch et al. [27] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient lifestyle and risk factors (questionnaire)

CTX = chemotherapy; Renitec® (Merck Sharp&Dohme GmbH, Vienna, Austria); Reducto spezial® (Temmler Pharma GmbH&Co.KG, Marburg, Germany); Trileptal® (Novartis Pharma GmbH, Vienna, Austria); Seroquel® (AstraZeneca GmbH, Vienna, Austria).

DEXA currently is the most commonly used technique to quantify BMD in clinical practice, and therefore was our method of choice [9]. We based our evaluation on the z-score system to compare BMD values of our young patients in conjunction with the t-score, used for the WHO osteoporosis definition [34, 41]. The main difference between the two scores was the control group to which the DEXA result was related [41]. In general, we believed premature bone loss in young patients was better described as low bone density for chronologic age than with the terms osteopenia and osteoporosis [2]. Nevertheless, for reasons of simplicity and comparability, we used z-scores between −1 SD and −2 SD as osteopenia and z-scores less than −2 SD as osteoporosis [34]. None of the eight patients who received radiotherapy had DEXA measurement at the site of radiation. The DEXA scans were obtained a minimum of 1 year after diagnosis (mean, 7 ± 5 years; range, 1–18 years).

Blood samples were taken in the morning after an overnight fast. The laboratory analyses included a general serum profile, bone metabolism, genetic analysis of lactose intolerance, and functional status of the thyroid gland, hypophysis, and gonads.

For calculations, we used R 2.12.0 (R foundation, Vienna, Austria). We assessed our patients' BMD by using the scoring system and compared laboratory results with standardized ranges. We determined differences in BMD and laboratory values between the Ewing's and osteosarcoma groups using the exact Wilcoxon rank sum test. To achieve more power compared with Bonferroni corrections, we used a global test according to Goeman et al. [12], which was developed for comparison of two groups with respect to many measurements. For evaluation of differences in lactose intolerance, we double checked using the exact Wilcoxon rank sum test and the model free likelihood-ratio test. To identify possible influencing factors on our patients’ BMD, we tested correlations with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (except for sex for which we used the Wilcoxon test), Bonferroni-corrected when necessary owing to multiple DEXA testing.

Results

Twenty-one percent of our patients had osteoporosis (z-score lower than –2 SD) and 37% had osteopenia (z-score between −1 SD and −2 SD) in a least one measuring site (Fig. 2). We recorded the mean BMD values and z-scores (Table 3). In tumors affecting the weightbearing bones, we found a lower BMD in the limb with the primary tumor location (femoral neck, p < 0.001; total femur, p = 0.0019). We therefore concentrated our femoral evaluation on the unaffected side, but excluded six patients who had data available only for the affected limb. Fifteen of the 43 patients had 17 nonvertebral fractures, 14 attributable to trauma and three associated with tumors before chemotherapy (one patient in each tumor group had two fractures at different times and sites). After chemotherapy, seven of the 43 patients had nontraumatic and nontumor-associated fractures (Table 4). Five of these patients had low BMD levels in at least one site. We found normal baseline serum calcium values, whereas serum phosphate decreased below the reference limit in 10 patients and median levels of all 43 patients ranged in the lower third of the reference range (Table 5). Our patients showed increases in bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (86%), N-terminal telopeptide procollagen (60%), osteocalcin (47%), beta-CrossLaps (65%), tartrate resistant alkaline phosphatase (23%), and osteoprotegerin (26%), all with a general upward tendency, and decreased receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) levels (51%). Thyroid hormones were normal. Increases in growth hormone were observed in 10 patients and insulinlike growth factor-1 in 12 patients. Free (bioactive) testosterone in patients older than 17 years tended toward the lower reference limit paralleled by increased follicle stimulating hormone in 15 patients and luteinizing hormone in eight. Other than BMD reduction and laboratory disturbances, we found no common characteristics of patients with osteoporosis compared with those without.

Fig. 2A–F.

The graphs show the results of DEXA measurement in reference to the z-score system. The percentage distributions of osteoporosis (dark), osteopenia (middle), and normal BMD (light) in (A) the lumbar spine, (B) the femoral neck, and (C) the total femur are presented. In context with patients' ages, the exact evaluated z-scores and their distribution among the two tumor entities (Ewing’s sarcoma - green; osteosarcoma - blue) in the (D) lumbar spine, (E) the femoral neck, and (F) the total femur are shown.

Table 3.

Mean bone mineral densities (BMD) [g/cm²]

| Parameter | Number | BMD (mean ± SD) | z-score (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lumbar spine L1–L4 (n = 43) | |||

| Ewing’s sarcoma (n = 18) | |||

| Normal BMD | 8 | 1.136 ± 0.135 | −0.013 ± 0.591 |

| Osteopenia | 5 | 0.991 ± 0.036 | −1.610 ± 0.123 |

| Osteoporosis | 5 | 0.880 ± 0.049 | −2.455 ± 0.272 |

| Osteosarcoma (n = 25) | |||

| Normal BMD | 17 | 1.173 ± 0.187 | 0.253 ± 0.869 |

| Osteopenia | 6 | 0.987 ± 0.052 | −1.600 ± 0.302 |

| Osteoporosis | 2 | 0.981 ± 0.050 | −2.238 ± 0.137 |

| Total (n = 43) | |||

| Normal BMD | 25 | 1.161 ± 0.173 | 0.168 ± 0.801 |

| Osteopenia | 11 | 0.989 ± 0.045 | −1.605 ± 0.238 |

| Osteoporosis | 7 | 0.909 ± 0.067 | −2.393 ± 0.260 |

| Femoral neck (tumor unaffected side) (n = 37) | |||

| Ewing’s sarcoma (n = 17) | |||

| Normal BMD | 8 | 0.971 ± 0.108 | −0.075 ± 0.642 |

| Osteopenia | 6 | 0.851 ± 0.072 | −1.483 ± 0.241 |

| Osteoporosis | 3 | 0.742 ± 0.021 | −2.467 ± 0.386 |

| Osteosarcoma (n = 20) | |||

| Normal BMD | 13 | 1.030 ± 0.160 | 0.192 ± 0.876 |

| Osteopenia | 6 | 0,831 ± 0,055 | −1.476 ± 0.262 |

| Osteoporosis | 1 | 0.670 ± 0.000 | −2.300 ± 0.000 |

| Total (n = 37) | |||

| Normal BMD | 21 | 1.008 ± 0.146 | 0.090 ± 0.805 |

| Osteopenia | 12 | 0.841 ± 0.065 | −1.475 ± 0.252 |

| Osteoporosis | 4 | 0.724 ± 0.036 | −2.425 ± 0.342 |

| Total femur (tumor unaffected side) (n = 37) | |||

| Ewing’s sarcoma (n = 17) | |||

| Normal BMD | 10 | 1.002 ± 0.111 | −0.190 ± 0.536 |

| Osteopenia | 4 | 0.872 ± 0.045 | −1.325 ± 0.228 |

| Osteoporosis | 3 | 0.717 ± 0.028 | −2.567 ± 0.262 |

| Osteosarcoma (n = 20) | |||

| Normal BMD | 13 | 1.044 ± 0.168 | 0.146 ± 0.918 |

| Osteopenia | 6 | 0.840 ± 0.055 | −1.533 ± 0.221 |

| Osteoporosis | 1 | 0.638 ± 0.000 | −2.700 ± 0.000 |

| Total (n = 37) | |||

| Normal BMD | 23 | 1.026 ± 0.148 | 0.000 ± 0.793 |

| Osteopenia | 10 | 0.853 ± 0.054 | −1.450 ± 0.246 |

| Osteoporosis | 4 | 0.698 ± 0.042 | −2.600 ± 0.235 |

BMD = bone mineral density.

Table 4.

BMDs [g/cm2] and z-scores of patients with fractures

| Location of fracture | Time after CTX (months) | Type of tumor | L1–L4 | Femoral neck (tumor unaffected) |

Total femur (tumor unaffected) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMD | z-score | BMD | z-score | BMD | z-score | |||

| Proximal femur | 36 | OS | 0.974 | −1.2 | 0.670 | −2.3 | 0.638 | −2.7 |

| Proximal femur | 72 | ES | 0.842 | −2.3 | 0.619* | −2.7 | 0.582* | −3.1 |

| Distal femur | 192 | OS | 1.065 | −1.2 | 0.821* | −1.8 | 0.689* | −2.9 |

| Distal femur, proximal tibia | 29 | ES | 0.891 | −2.7 | 0.759 | −2.1 | 1.111 | 0.4 |

| Proximal tibia | 32 | OS | 1.102 | −0.5 | 0.962 | −0.3 | 0.989 | −0.3 |

| Proximal tibia | 30 | OS | 0.921 | 0.1 | 0.563* | −3.2 | 0.548* | −3.1 |

| Finger | 72 | OS | 1.415 | 1.6 | 1.102 | 0.9 | 1.133 | 1.0 |

* Data for the tumor-affected side; CTX = chemotherapy; BMD = bone mineral density; ES = Ewing’s sarcoma; OS = osteosarcoma.

Table 5.

Laboratory values

| General laboratory values | Ewing's sarcoma (n = 18) | Osteosarcoma (n = 25) | Total (n = 43) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrolytes | ||||

| Total calcium (2.2–2.65 mmol/L) | 2.4 (2.3–2.6) | 2.4 (2.2–2.6) | 2.4 (2.2–2.6) | 0.46 |

| Phosphate (2.6–4.5 mg/dL) | 2.7 (1.9–4.1) | 3.3 (2.2–4.4) | 3.1 (1.9–4.4) | 0.10 |

| Kidney | ||||

| Creatinine (0.5–1.0 mg/dL) | 1.1 (0.8–1.8) | 0.9 (0.4–1.3) | 1 (0.4–1.8) | 0.04 |

| Urea (10–45 mg/dL) | 30.5 (16–57) | 30 (19–55) | 30 (16–57) | 0.72 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 14.2 (7.5–26.6) | 14 (8.9–25.7) | 14 (7.5–26.6) | 0.72 |

| Liver | ||||

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase (−38 U/L) | 15.5 (10–511) | 17 (7–115) | 17 (7–511) | 0.58 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (−30 U/L) | 29 (17–93) | 25 (17–56) | 27 (17–93) | 0.49 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (−35 U/L) | 21.5 (11–186) | 22 (10–119) | 22 (10–186) | 0.90 |

| Serum proteins | ||||

| Total globulin (6.6–8.3 g/dL) | 7.9 (6.5–9.1) | 7.7 (6.8–9.0) | 7.7 (6.5–9.1) | 0.34 |

| Albumin (3.5–5.3 g/dL) | 5.2 (4.2–5.9) | 5.0 (4.2–5.5) | 5.1 (4.2–5.9) | 0.04 |

| Endocrinology | ||||

| Thyroid gland | ||||

| Thyroid stimulating hormone (0.1–4 μU/mL) | 1.5 (1.1–3.3) | 1.6 (0.4–2.7) | 1.6 (0.4–3.3) | 0.53 |

| Trijodthyronin (3–6.3 pmol/L) | 5.3 (4.1–6.4) | 5.2 (4–6.8) | 5.2 (4–6.8) | 0.25 |

| Thyroxin (9.5–24 pmol/L) | 15.9 (12.1–22.9) | 14.4 (11.2–24.2) | 14.8 (11.2–24.2) | 0.98 |

| Parathyroid gland/bone metabolism | ||||

| Parathyroid hormone (15–65 pg/mL) | 38.1 (18.7–65.6) | 45.7 (21.8–77.8) | 43.3 (18.7–77.8) | 0.45 |

| 25 (OH) vitamin D3 (30–60 ng/mL) | 15.8 (5–50.2) | 16.6 (7.6–104.6) | 16.4 (5–104.6) | 0.47 |

| Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (μg/L)* | 31.4 (16.6–75.5) | 29.4 (15.8–97.8) | 31.1 (15.8–97.8) | 0.58 |

| Osteocalcin (1–35 ng/mL) | 30.7 (1.5–255.7) | 34.4 (15–168.2) | 31.9 (1.5–255.7) | 0.79 |

| N-terminal telopeptide procollagen (ng/mL)† | 62.4 (29.7–417.3) | 81.1 (31.5–722.4) | 78.8 (29.7–722.4) | 0.52 |

| Osteoprotegerin (0.7–4.2 pmol/L) | 3.2 (0.1–7.0) | 3.6 (1.3–7.7) | 3.5 (0.1–7.7) | 0.33 |

| RANKL (0.04–0.85 pmol/L) | 0.04 (0.0–0.4) | 0.02 (0.0–1.1) | 0.03 (0–1.1) | 0.56 |

| Tartrate resistant alkaline phosphatase (U/L)‡ | 3.1 (1.7–5.6) | 3.4 (2.4–11.5) | 3.3 (1.7–11.5) | 0.21 |

| Beta-CrossLaps (ng/mL)§ | 0.7 (0.2–3.7) | 0.6 (0.3–2.8) | 0.6 (0.2–3.7) | 0.69 |

| Gonads | ||||

| Testosterone total (♂) (2.41–8.3 ng/mL) | 4.7 (0.2–8.8) | 4.8 (0.1–8.8) | 4.7 (0.1–8.8) | 0.70 |

| Testosterone free (♂) (6.69–54.69 pg/mL) | 18.2 (2.4–34.3) | 15.7 (0.2–28.1) | 16.4 (0.2–34.3) | 0.39 |

| Sexual hormone binding protein (♂) (16–76 nmol/L) | 37.1 (22.3–111.1) | 37 (23.3–200) | 37.1 (22.3–200) | 0.78 |

| Testosterone total (♀) (ng/mL) | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) | 0.4 (0.1–0.6) | 0.4 (0.1–0.6) | 0.76 |

| Testosterone free (♀) (pg/mL) | 1.5 (1–2.9) | 1.7 (0.8–3) | 1.6 (0.8–3) | 0.89 |

| Sexual hormone binding globulin (♀) (24–230 nmol/L)¶ | 118.6 (35.1–173.8) | 47.1 (22.8–133.6) | 88.5 (22.8–173.8) | 0.07 |

| Neuroendocrinology | ||||

| Growth hormone (0–7 ng/mL) | 2.8 (0.2–11.8) | 0.6 (0.1–15.7) | 1.3 (0.1–15.7) | 0.33 |

| Insulinlike growth factor-1 (100–300 ng/mL) | 230 (112–489) | 242 (72.6–418) | 238 (72.6–489) | 0.59 |

| Gynecologic/gonadal laboratory | ||||

| Follicle stimulating hormone (♂) (1.3–12 mIU/mL) | 6.3 (1–31.9) | 8.9 (0.9–33.7) | 6.8 (0.9–33.7) | 0.68 |

| Follicle stimulating hormone (♀) (< 0.1–67.5 mIU/mL) | 40.4 (0.3–115.4) | 7.3 (2.4–183.7) | 13.3 (0.3–183.7) | 0.28 |

| Luteotrope hormone (♂) (0.8–8.5 mIU/mL) | 6.3 (0.4–13.8) | 4.5 (0.3–16) | 5.6 (0.3–16) | 0.20 |

| Luteotrope hormone (♀) (1.1–20 mIU/mL) | 18.2 (0.3–48.4) | 5.6 (1.7–71.8) | 13.8 (0.3–71.8) | 0.82 |

* 7.5–20.6 μg/L (♂), 5.8–14.8 μg/L (♀); †16–67 ng/mL (♂), 20–75 ng/mL (♀); ‡2.18–3.94 U/L (♂), 1.81–3.37 U/L (♀); §0.08–0.46 ng/mL (♂), 0.03–0.37 ng/mL (♀); ¶89–379 nmol/L with oral contraceptives; all female ranges are valid for premenopausal women.

Differences between the two tumor types trended (p = 0.053) toward lower BMD values in Ewing's sarcoma, especially in the lumbar spine. Creatinine (p = 0.04) and albumin (p = 0.04) were lower in patients with osteosarcoma.

We found vitamin D deficiency in 38 of the 43 (88%) patients with mean parathyroid hormone levels in the normal range. Genetically defined lactose intolerance (Table 6) occurred in 16 patients and was observed in similar proportions of patients with Ewing's sarcoma and osteosarcoma (p = 0.363) and did not correlate (p = 1.00) with the BMD measured. Greater height (p = 0.03), weight (p < 0.001), and BMI (p < 0.001) correlated with a greater BMD in all sites. Sex (p = 0.29), age at diagnosis (p = 0.52), and the time between chemotherapy and our investigation (p = 0.21) did not affect the outcome. In females, neither age at menarche (p = 0.39) nor the time between menarche and chemotherapy (p = 1.00) were influencing.

Table 6.

Relation of lactose intolerance and measured BMD*

| Lactose intolerance | Number of incidences (n = 43) | Lumbar spine | Number of incidences (n = 37) | Femoral neck | Total femur |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT | 10 | 1.086 ± 0.183 | 9 | 0.948 ± 0.188 | 0.952 ± 0.209 |

| TC | 17 | 1.052 ± 0.092 | 14 | 0.919 ± 0.112 | 0.934 ± 0.125 |

| CC | 16 | 1.096 ± 0.220 | 14 | 0.910 ± 0.166 | 0.948 ± 0.169 |

BMD = bone mineral density; * mean BMD values ± SD; TT = no genetic determination for lactose intolerance; TC = little to no genetic determination for lactose intolerance; CC = genetic determination for lactose intolerance.

Discussion

Bone loss after childhood chemotherapy might be underestimated in patients with bone sarcoma. HD-MTX, a standard agent in osteosarcoma protocols, reportedly has reduced BMD [8, 17]. The literature, however, shows decreased BMD in patients with Ewing's sarcoma treated without HD-MTX [33]. Thus, it is unclear whether osteoporosis after chemotherapy relates to HD-MTX or to other factors. We therefore evaluated whether (1) young patients with bone sarcoma had premature BMD reduction, (2) patients treated with MTX had lower BMD, and (3) other factors (eg, lactose intolerance or vitamin D deficiency) posed additional risks for low BMD.

Our study had several limitations. First, we had a relatively small number of participants owing to the rarity of the tumor entities, mortality rate, and inclusion criteria concerning age. Second, the different intervals between chemotherapy and investigation varied from 9 months to 18 years. Nevertheless, this enabled us to further evaluate a possible correlation between time of remission and BMD. Third, six of the 43 patients were excluded from the femoral BMD analysis owing to the absence of bilateral femoral DEXA data. However, we still had a study population of 43 patients with lumbar spine and laboratory data. Further, the lumbar spine has been assumed to be even more sensitive to therapeutic modalities owing to the large mass of trabecular bone [1, 11]. Fourth, we compared our DEXA data with a scoring system instead of using a normal study population, mainly for higher reliability because of the large number of patients included in the database. Fifth, we tested potential influencing factors on BMD only in univariable analysis, finding height, weight, and BMI influential. In a multivariate analysis, some of those factors may not independently predict BMD. Sixth, our study was set in spring, when seasonal vitamin D deficiency may have overshadowed the influence of chemotherapy. Nevertheless, we diagnosed a high percentage of patients with BMD reduction, which was unlikely to be attributable to seasonal vitamin D imbalances.

We found decreased bone mineral density levels in 25 of the 43 patients (58%) compared with age- and gender-related pairs in at least one measuring point. We also compared our data with that in the literature (Table 7). The studies varied in study population and followup times; nevertheless, both revealed a remarkable number of patients with BMD reduction and fractures [17, 33], which are often the first indicator of bone loss. The estimated lifetime-fracture risk attributable to osteoporosis reportedly is exponentially related to BMD, which decreases up to 10-fold faster if related to tumor treatment, especially in association with hypogonadism [13]. One study suggested an association between osteoporotic fractures in patients’ history and a higher risk for subsequent events [13]. However, in children, the absence of fractures did not automatically imply an age-related healthy bone status because they often did not fracture, even if very low z-score levels were reached [22]. Refinement of our DEXA scans was reached by laboratory evaluation. Our patients had an increase in bone-specific serum parameters, indicating higher rates of skeletal remodeling. This coincided with findings in the literature, where lower rates of skeletal remodeling correlated with reaching higher bone mass during puberty [37]. A negative correlation between markers of bone formation and resorption to BMD also was reported in one study [33], whereas in another study this correlation was seen only concerning bone resorption [17]. Increased growth hormone and insulinlike growth factor-1, both important for bone growth (childhood) and maintenance (adulthood), further correlated with higher bone metabolism [10, 32, 38], documenting the growth period of some of our patients.

Table 7.

Comparison of our study data with the literature

| Study | Study participants | Mean age at followup (years) (± SD) | Mean followup times (years) (± SD) | Tumor localization in weightbearing bones (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Ewing's sarcoma | Osteosarcoma | Male | Female | Ewing's sarcoma | Osteosarcoma | Ewing's sarcoma | Osteosarcoma | Yes | No | |

| Holzer et al. [17] | 48 | 0 | 48 | 22 | 26 | NA | 31 (± 4.24) | NA | 16 (± 2.2) | 92% | 8% |

| Ruza et al. [33] | 63 | 25 | 38 | 32 | 31 | 19.13 (± 4.20) | 20.65 (± 4.42) | 6 (± 3.73) | 6 (± 3.67) | 83% | 17% |

| Current study | 43 | 18 | 25 | 26 | 17 | 26.09 (± 7.61) | 27.21 (± 10.34) | 8 (± 4.2) | 7 (± 4.7) | 79% | 21% |

| Fractures | Number of patients (%) | Score | Method | Measuring sites | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before CTX | After CTX | Normal BMD | Osteopenia | Osteoporosis | ||||

| Holzer et al. [17] | 16 | 18 | 17 (35%) | 21 (43.7%) | 10 (20.8%) | t-score | DEXA | lumbar spine, proximal femur (nonoperated side) |

| Ruza et al. [33] | 17 total | 36 (57.1%)* | 21 (33.3%)* | 6 (9.52%)* | z-score | DEXA | lumbar spine (*), femoral neck (tumor unaffected side) (°) | |

| 36 (57.1%)° | 16 (25.4%)° | 11 (17.5%)° | ||||||

| Current study | 17 | 7 | 18 (41.9%) | 16 (37.2%) | 9 (20.9%) | z-score | DEXA | lumbar spine; femoral neck, total femur (tumor unaffected side) |

CTX = chemotherapy; BMD = bone mineral density; NA = not available.

Consistent with one report [33], our observations did not support the notion that patients with osteosarcoma who had HD-MTX in their treatment schemes have lower BMD levels than patients with Ewing's sarcoma treated without HD-MTX. Rather, we observed a trend in Ewing's sarcoma toward lower BMD levels, especially in the lumbar spine, which seemed to present a higher sensitivity to osteopenic agents because of the trabecular bone as the main component [1, 11]. Longer average treatment duration in Ewing's sarcoma (10–12 months) compared with osteosarcoma (6–12 months) might have contributed to this outcome as well [15].

We found a high percentage of vitamin D deficiency (88%) which might have contributed to the observed increase in bone-turnover. Inadequate vitamin D levels have been related to children’s inability of attaining their genetically programmed peak bone mass, and, in adults, vitamin D deficiency has led to severe bone disturbances [16, 29, 39]. Secondary hyperparathyroidism attributable to vitamin D deficiency with consecutive renal loss of phosphate may have resulted in an increased bone-turnover, impaired mineralization, and loss of BMD, along with higher incidences of fractures [24, 28, 30]. This may explain why bone loss was unaffected by sex, age at the time of chemotherapy, and followup time. Additionally, we found a relatively high percentage of patients with genetic determination for lactose intolerance (37%) as compared with the Central European average (20%–40%) [27]. Patients’ tending to avoid intolerance symptoms by reducing calcium-rich dairy products might have had a greater impact than the intolerance [5, 18, 20, 25]. Low calcium intake would correlate with an increase in serum parathyroid hormone and increased bone turnover [35]. Serum calcium measurements were not suitable to prove sufficient nutritional calcium supply because changes may have occurred by increased bone mobilization attributable to immobilization. Physical inactivity possibly influenced femoral BMD reduction in both groups, and was supposed to show higher impact on weightbearing bones than on the lumbar spine [1, 26]. Bone loss attributable to immobilization has been reported to be greatest during the first weeks of disuse, and its duration strongly affected the amount of BMD reduction [36] . In this context, a patient’s attitude to favor the surgically treated limb [17] provided a reasonable explanation for the lower BMD levels measured in the tumor-affected leg compared with the unaffected one.

Our data support the notions that (1) premature reduction of BMD in young survivors of bone sarcoma should be considered in a patient’s management, (2) BMD deficits occurred independently from the tumor entity, and (3) BMD reduction possibly was potentiated by vitamin D deficiency and lactose intolerance. Therefore, we suggest regular endocrinology consultations and eventual adequate osteoprotective treatment; we recommend vitamin D and calcium. Owing to the results of our investigation, we offered consultation and treatment to the patients in this study and for all future patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Franz Quehenberger PhD, Institute of Medical Informatics, Statistics and Documentation, for statistical analysis, and Thomas Lovse MD, Karin Novotny, and Andreas Frings for their assistance.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of their immediate family, has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Arikoski P, Komulainen J, Riikonen P, Voutilainen R, Knip M, Kröger H. Alterations in bone turnover and impaired development of bone mineral density in newly diagnosed children with cancer: a 1-year prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3174–3181. doi: 10.1210/jc.84.9.3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baroncelli GI, Bertelloni S, Sodini F, Saggese G. Osteoporosis in children and adolescents: etiology and management. Paediatr Drugs. 2005;7:295–323. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200507050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger DP, Engelbrecht R, Mertelsmann R. [The Red Book - Hämatology and Internistic Onkology] [in German] Landsberg, Germany: Hüthig Jehle Rehm GmbH; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bielack S, Kempf-Bielack B, Schwenzer D, Birkfellner T, Delling G, Ewerbeck V, Exner GU, Fuchs N, Göbel U, Graf N, Heise U, Helmke K, Hochstetter AR, Jürgens H, Maas R, Münchow N, Salzer-Kuntschik M, Treuner J, Veltmann U, Werner M, Winkelmann W, Zoubek A, Kotz R. [Neoadjuvant therapy for localized osteosarcoma of extremities; results from the Cooperative Osteosarcoma study group COSS of 925 patients] [in German] Klin Pädiatr. 1999;211:260–270. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1043798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bob A, Bob K. [Internal Medicine] [in German] Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrle D, Bielack SS. Current strategies of chemotherapy in osteosarcoma. Int Orthop. 2006;30:445–451. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0192-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunst J, Ahrens S, Paulussen M, Rübe C, Winkelmann W, Zoubek A, Harms D, Jürgens H. Second malignancies after treatment for Ewing’s sarcoma: a report of the CESS-studies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:379–384. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ecklund K, Laor T, Goorin AM, Connolly LP, Jaramillo D. Methothrexate osteopathy in patients with osteosarcoma. Radiology. 1997;202:543–547. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.2.9015088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilsanz V. Bone density in children: a review of the available techniques and indications. Eur J Radiol. 1998;26:177–182. doi: 10.1016/S0720-048X(97)00093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giustina A, Mazziotti G, Canalis E. Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factors, and the skeleton. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:535–559. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gnudi S, Butturini L, Ripamonti C, Avella M, Bacci G. The effects of methotrexate (MTX) on bone: a densitometric study conducted on 59 patients with MTX administered at different doses. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1988;14:227–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goeman JJ, Geer SA, Kort F, Houwelingen HC. A global test for groups of genes: testing association with a clinical outcome. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:93–99. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guise TA. Bone loss and fracture risk associated with cancer therapy. Oncologist. 2006;11:1121–1131. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-10-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herold G. [Internal Medicine] [in German] Köln, Germany: Herold; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogendoorn PC, ESMO/EUROBONET Working Group. Athanasou N, Bielack S, Alava E, Dei Tos AP, Ferrari S, Gelderblom H, Grimer R, Hall KS, Hassan B, Hogendoorn PC, Jurgens H, Paulussen M, Rozeman L, Taminiau AH, Whelan J, Vanel D. Bone sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 5):v204–v213. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holick MF. High prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy and implications for health. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:353–373. doi: 10.4065/81.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holzer G, Krepler P, Koschat MA, Grampp S, Dominkus M, Kotz R. Bone mineral density in long-term survivors of highly malignant osteosarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:231–237. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.85B2.13257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honkanen R, Pulkkinen P, Järvinen R, Kröger H, Lindstedt K, Tuppurainen M, Uusitupa M. Does lactose intolerance predispose to low bone density? A population-based study of perimenopausal Finnish women. Bone. 1996;19:23–28. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(96)00107-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson KA, Savaiano DA. Lactose maldigestion, calcium intake and osteoporosis in African-, Asian-, and Hispanic-Americans. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20(2 suppl):198S–207S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2001.10719032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kager L, Zoubek A, Dominkus M, Lang S, Bodmer N, Jungt G, Klingebiel T, Jürgens H, Gadner H, Bielack S, COSS Study Group Osteosarcoma in very young children. Cancer. 2010;116:5316–5324. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaste SC. Skeletal toxicities of treatment in children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(2 suppl):469–473. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaste SC, Chesney RW, Hudson MM, Lustig RH, Rose SR, Carbone LD. Bone mineral status during and after therapy of childhood cancer: an increasing population with multiple risk factors for impaired bone health. (Comment on J Bone Miner Res. 2009;14:2002–2009). J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:2010–2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Krall EA, Sahyoun N, Tannenbaum S, Dallal GE, Dawson-Hughes B. Effect of vitamin D intake on seasonal variations in parathyroid hormone secretion in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1777–1783. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198912283212602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kull M, Kallikorm R, Lember M. Impact of molecularly defined hypolactasia, self-perceived milk intolerance and milk consumption on bone mineral density in a population sample in Northern Europe. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:415–421. doi: 10.1080/00365520802588117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minaire P. Immobilization osteoporosis: a review. Clin Rheumatol. 1989;8(suppl 2):95–103. doi: 10.1007/BF02207242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Obermayer-Pietsch BM, Bonelli CM, Walter DE, Kuhn RJ, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Berghold A, Goessler W, Stepan V, Dobnig H, Leb G, Renner W. Genetic predisposition for adult lactose intolerance and relation to diet, bone density, and bone fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:42–47. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.0301207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ooms ME, Lips P, Roos JC, Vijgh WJ, Popp-Snijders C, Bezemer PD, Bouter LM. Vitamin D status and sex hormone binding globulin: determinants of bone turnover and bone mineral density in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:1177–1184. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Outila TA, Kärkkäinen MU, Lamberg-Allardt CJ. Vitamin D status affects serum parathyroid hormone concentrations during winter in female adolescents: associations with forearm bone mineral density. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:206–210. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pasco JA, Henry MJ, Kotowicz MA, Sanders KM, Seeman E, Pasco JR, Schneider HG, Nicholson GC. Seasonal periodicity of serum vitamin D and parathyroid hormone, bone resorption, and fractures: the Geelong Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:752–758. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.040125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paulussen M, Craft AW, Lewis I, Hackshaw A, Douglas C, Dunst J, Schuck A, Winkelmann W, Köhler G, Poremba C, Zoubek A, Ladenstein R, Berg H, Hunold A, Cassoni A, Spooner D, Grimer R, Whelan J, McTiernan A. European Intergroup Cooperative Ewing’s Sarcoma Study-92. Results of the EICESS-92 Study: two randomized trials of Ewing’s sarcoma treatment: cyclophosphamide compared with ifosfamide in standard-risk patients and assessment of benefit of etoposide added to standard treatment in high-risk patients. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4385–4393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perrini S, Laviola L, Carreira MC, Cignarelli A, Natalicchio A, Giorgino F. The GH/IGF1 axis and signaling pathways in the muscle and bone: mechanisms underlying age-related skeletal muscle wasting and osteoporosis. J Endocrinol. 2010;205:201–210. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruza E, Sierrasesúmaga L, Azcona C, Patiño-Garcia A. Bone mineral density and bone metabolism in children treated for bone sarcomas. Pediatr Res. 2006;59:866–871. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000219129.12960.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sala A, Barr RD. Osteopenia and cancer in children and adolescents: the fragility of success. Cancer. 2007;109:1420–1431. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Segal E, Dvorkin L, Lavy A, Rozen GS, Yaniv I, Raz B, Tamir A, Ish-Shalom S. Bone density in axial and appendicular skeleton in patients with lactose intolerance: influence of calcium intake and vitamin D status. J Am Coll Nutr. 2003;22:201–207. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2003.10719294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sievänen H. Immobilization and bone structure in humans. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;503:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slemenda CW, Peacock M, Hui S, Zhou L, Johnston CC. Reduced rates of skeletal remodeling are associated with increased bone mineral density during the development of peak skeletal mass. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:676–682. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ueland T. Bone metabolism in relation to alterations in systemic growth hormone. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2004;14:404–417. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unuvar T, Buyukgebiz A. Nutritional rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children and adolescents. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2010;7:283–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sluis IM, Heuvel-Eibrink MM. Osteoporosis in children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(2 suppl):474–478. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wasilewski-Masker K, Kaste SC, Hudson MM, Esiashvili N, Mattano LA, Meacham LR. Bone mineral density deficits in survivors of childhood cancer: long-term follow-up guidelines and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e705–e713. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]