Abstract

A collection of 113 epidemiologically unrelated Streptococcus agalactiae strains were studied (group B streptococcus; GBS): they belonged to different serotypes and were isolated from pregnant women in China and Russia. The insertion sequence ISSa4 was found in 21 of 113 strains (18,6%). All of the strains with ISSa4 belonged to serotypes II and II/c and were characterized by the presence of IS1381 and IS861 as well as the absence of IS1548 and GBSi1. All of the strains with ISSa4 possessed both bca and bac virulence genes coding for α and β antigens, respectively. Among 21 ISSa4-positive strains, 13 different HindIII patterns (D1 to D13) hybridizing with an ISSa4 probe were found. One of them (D13) contained a single HindIII hybridization fragment 6.5 kb in size that was found to be specific for all ISSa4-positive GBS strains. Multiple target sites for insertions of ISSa4 were identified and included a putative pathogenicity island, “housekeeping” genes, and intergenic regions, as well as the genes for hypothetical proteins. No significant similarity was observed in the sequences of the target genes for ISSa4 insertions, in the relative location of the target genes on the chromosome, or the biological functions of the encoded proteins. The possible significance of ISSa4-based differentiation of the strains and the presence of possible “hot spots” for insertions of ISSa4 in GBS genome are discussed.

Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus; GBS) is an important human pathogen that causes significant pathology during pregnancy and in neonates (17). GBS strains are subclassified into nine serotypes according to the immunologic reactivity of the polysaccharide capsule. Approximately one-third of GBS clinical isolates in the United States belong to serotype V (9). GBS strains of serotypes II and III predominate in the People's Republic of China, and GBS strains of the serotypes VI and VIII predominate in Japan (12). Serotype III is responsible for most cases (80%) of neonatal GBS meningitis (19).

Mobile genetic elements, such as bacteriophages, transposons, and insertion sequences (IS elements), can contribute to microbial evolution and virulence by mediating genetic recombination events (13). Numerous reports on the presence of IS elements in GBS have been published (4, 7, 8, 11, 18, 20, 21). Some of the IS elements were found to be integrated in virulence genes that influenced the changes in virulence properties of GBS (8, 11, 20). Following the complete sequencing of two GBS strains, several new IS elements were identified along with their precise location on the chromosome (6, 22). ISSa4, as a member of IS982 family, has been previously found by Southern hybridization in four GBS strains and sequenced (20). Until now, it had not been found in other bacterial species. Also ISSa4 was not found in the genomes of the two GBS strains sequenced (6, 22). Furthermore, the nucleotide sequence of ISSa4 did not reveal any significant similarity to other known bacterial IS elements.

Recently we examined the distribution of IS861 and IS1548 among the collection of GBS strains and analyzed the relative locations of IS861 and IS1548 on the chromosomal DNA (4). We could reveal several genetic lineages of GBS based on restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of IS861 and IS1548 and the analysis of the chromosomal DNA by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. The goal of the present study was to further examine the same collection of GBS strains in order to investigate the distribution of ISSa4 among GBS strains of different serotypes and to analyze the copy number of ISSa4 in different strains. Another goal of the study was to evaluate ISSa4-based differentiation of the strains and to identify the target sites for insertions of ISSa4 copies in the GBS genome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 113 epidemiologically unrelated GBS strains were analyzed. Among them, 100 strains were isolated in different regions of the People's Republic of China in 1996 to 2000, and 13 strains were isolated in Saint Petersburg, Russia, in 1989 to 1995. All GBS strains were isolated from the healthy pregnant women without any symptoms of streptococcal diseases. Serotyping was done with the set of type-specific antisera (Ia to VIII) from the WHO Collaborating Centers for Reference and Research on Streptococci (Saint Petersburg, Russia, and Beijing, People's Republic of China). Serotyping of the strains revealed different serological types (Ia, Ia/c, Ib/c, II, II/c, II/R, III, III/R, and V). Five strains were nontypeable (Table 1). Bacteria were grown either in Todd-Hewitt broth or on 1.5% horse blood agar at 37°C overnight.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of ISSa4 among GBS strains of different serotypes

| Serotype | No. of strains

|

|

|---|---|---|

| ISSa4 negative | ISSa4 positive | |

| Ia | 15 | 0 |

| Ia/c | 9 | 0 |

| Ib/c | 12 | 0 |

| II | 1 | 4 |

| II/c | 7 | 17 |

| II/R | 8 | 0 |

| III | 13 | 0 |

| III/R | 18 | 0 |

| V | 4 | 0 |

| Nontypeable | 5 | 0 |

| Total | 92 | 21 |

General DNA techniques.

Most of the molecular genetic procedures were carried out according to Maniatis et al. (14). Southern hybridization of HindIII-digested chromosomal DNA with an ISSa4 probe was accomplished with the Enzo DNA labeling and detection kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). PCR was carried out with 30 cycles of amplification steps of 30 s at 94°C, 1 min at 47 to 49°C (Table 2) and 1 min at 72°C. Sequencing of PCR products was performed with an ABI Prism 377 Perkin-Elmer sequencer and a BigDye terminator kit (Applied Biosystems). The primers used for cloning and sequencing are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in the present study

| Primer | Primer sequence (5′→3′) | Gene | PCR annealing temp (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 105 | GAGAGTTAGTCCCAATGAGCCA, forward | ISSa4 | 49 |

| 106 | TCCCTATACAGCTGATGGCAT, reverse | ISSa4 | 49 |

| 150 | CTGAGCTAGGTATTAAGTCGCAAC, forward | ISSa4 | 49 |

| 151 | AGCGTGTCTCAATGGTTCGT, reverse | ISSa4 | 49 |

| 131 | ATGACAGAGCTCGAGCGACTT, forward | IS861 | 49 |

| 132 | TATCAGCCTTCTTACCAACCTCA, reverse | IS861 | 49 |

| 127 | TTGCGCAGTTGAATTGGATAG, forward | IS1548 | 49 |

| 130 | TTCTCTAACTTCAATCTGTCCCCTA, reverse | IS1548 | 49 |

| 152 | GTTAAGCTTAGAAGATCTCCTCATGG, forward | IS1381 | 49 |

| 153 | CCTTGATAACCACTGTCTGCCA, reverse | IS1381 | 49 |

| 274 | GTAAAACGACGGCCAGTG, forward | PGEM-7zf(+) | 47 |

| 275 | CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCATG, reverse | PGEM-7zf(+) | 47 |

| L5 | TGTAAAGGACGATAGTGTGAAGAC, forward | bac | 48 |

| L6 | CATTTGTGATTCCCTTTTGC, reverse | bac | 48 |

| P4 | CAGGAGGGGAAACAACAGTAC, forward | bca | 49 |

| P5 | GTATCCTTTGTTCCATCTGGATACG, reverse | bca | 49 |

Computer analysis.

The sequences of the genes were accessed through the database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez). The sequences of the primers were designed with the computer program OLIGO. Computer analysis of DNA sequences was accomplished by using BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast). After electrophoresis, the sizes of DNA fragments were estimated with the program SEQAID by using a 100-bp ladder (Bio-Rad Laboratories) or λ HindIII fragments as DNA molecular size standards.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequence data reported in this paper appear in the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under accession numbers AY445916, AY449757, AY449758, AY449759, AY455996, AY455997, AY459524, AY461800, and AY461801.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Presence of ISSa4 in GBS strains.

The presence of ISSa4 in 113 human GBS strains was studied by PCR. Two forward primers (105 and 150) and two reverse primers (106 and 151) were used for amplification of the different regions of ISSa4. As a result, 21 of 113 strains (18.6%) were found to possess ISSa4. Interestingly, ISSa4 occurred among the strains of serological types II and II/c and was not found in any of the strains of other serotypes (Table 1).

In order to confirm the serotype-specific occurrence of ISSa4, an additional collection of 90 GBS strains of serotypes Ia, Ia/c, Ib/c, II, II/c, II/R, III, III/R, and V was analyzed. In this collection, each serotype was presented by 10 strains. As a result, ISSa4 was found in 13 of 90 GBS strains. Among these 13 strains, 8 strains belonged to serotype II/c and 5 strains belonged to serotype II that confirms the serotype-specific occurrence of ISSa4. This serotype-specific occurrence explains why ISSa4 was not discovered during the complete GBS genome sequencing of serotypes III and V (6, 22).

The presence of several other IS elements (i.e., IS1548, IS861, and IS1381) and intron GBSi1 was determined by PCR with the primers listed in the Table 2. Taken together, 9 different genetic variants were discovered among 113 strains tested (Table 3). All strains of serotype II/R possessed IS1381, IS861, and GBSi1. IS1548 was found among the strains of serotypes III and III/R. Taking into account the presence of other IS elements, the strains of serotypes III and III/R could be effectively classified into different IS-based genetic variants (Table 3). These results confirm the presence of different genetic lineages among the strains of serotypes III and III/R previously revealed by multilocus enzyme genotyping and ribotyping (1, 16). At the same time, strains of serotypes III and III/R were found to be different from the strains of other serotypes. These results are in agreement with previous publications that demonstrated the difference between restriction profiles of the strains of serological types III and III/R in comparison with the strains of other serotypes (2, 5, 10). The strains with ISSa4 belonged to serotypes II and II/c and were characterized by the presence of IS1381 and IS861 as well as the absence of IS1548 and GBSi1 (Table 3). Analysis of the presence of different IS elements in GBS strains revealed the mutually exclusive presence of IS1548, ISSa4, and GBSi1 in the GBS genome (Table 3). These data confirm the mutually exclusive presence of IS1548 and GBSi1 recently revealed (7). It is probable that the strains with ISSa4 represent a unique genetic lineage that is different from the strains with IS1548 and the strains with GBSi1.

TABLE 3.

IS-based genetic variants of GBS

| Genetic variant | Presence of IS elements and GBSi1 in GBS strains

|

No. of strains | Serotype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS1381 | IS861 | ISSa4 | IS1548 | GBSi1 | |||

| 1 | − | − | − | − | − | 29 | Different serotypes |

| 2 | + | − | − | − | + | 4 | Ib/c, II/c, V, NTa |

| 3 | + | − | − | − | − | 13 | Ia, Ia/c, Ib/c, II/c, III, NT |

| 4 | − | + | − | − | − | 5 | III |

| 5 | − | + | − | − | + | 7 | III/R |

| 6 | + | + | − | − | + | 9 | Ia/c, II/R |

| 7 | + | + | − | − | − | 12 | Ia, Ia/c, Ib/c, II/c, NT |

| 8 | + | + | + | − | − | 21 | II, II/c |

| 9 | + | + | − | + | − | 13 | III, III/R |

| Total | 113 | ||||||

NT, nontypeable.

As mentioned above, the strains of serotypes III and III/R were classified into different genetic variants. The same was true for GBS strains of other serotypes with exception of the strains of serotype II/R (Table 3). All of these data indicate that IS-based typing can be considered an additional tool for further differentiation of GBS strains.

Additional analyses of GBS strains for the presence of virulence genes bca and bac coding for α and β antigen, respectively, were performed (data not shown). Recently we demonstrated that the presence of bca and bac encoding for α and β antigens, respectively, could be used as a marker for differentiation of GBS strains into different genetic lineages (2, 3). In this study, it was found that 21 strains with ISSa4, including 4 strains of serotype II and 17 strains of serotype II/c (Table 1), possessed both bac and bca genes. Some other strains of different serotypes (Ia, Ia/c, Ib/c, II, and II/c) with the bca gene or both bca and bac genes lacked ISSa4. Taken together, these data indicate that one of the GBS clones of serotype II (II/c), with bac and bca genes as well as IS1381 and IS861, could be a recipient of ISSa4 due to the horizontal transfer from other organism.

RFLP of ISSa4.

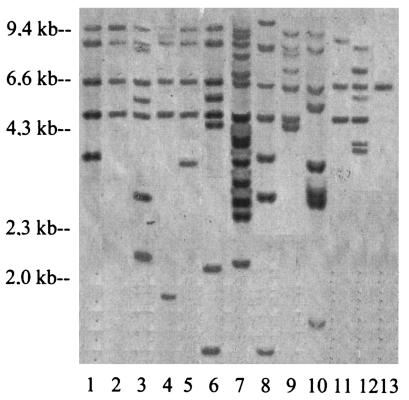

The chromosomal DNA of 21 GBS strains with ISSa4 were digested with HindIII and hybridized with the ISSa4 probe. The number of HindIII fragments hybridizing with the ISSa4 probe varied significantly in the strains; the largest number of HindIII fragments was 14, and the smallest number was 1. Taken together, 13 different HindIII hybridization patterns (D1 to D13) were found among 21 strains (Fig. 1), demonstrating the good discriminative value for differentiation of the strains containing ISSa4.

FIG. 1.

HindIII hybridization patterns with the ISSa4 probe. Lanes 1 to 13 correspond to D1 to D13 HindIII hybridization patterns with ISSa4 probe, respectively. The λ HindIII molecular size marker is shown on the left.

In this study, it was considered that each copy of ISSa4 did not contain a HindIII restriction site as was published for the recently sequenced ISSa4 (20). Based on this hypothesis, the number of ISSa4 copies could presumably correspond to the number of HindIII fragments hybridizing with the ISSa4 probe. Hybridization pattern D13 was presented by a single 6.5-kb HindIII fragment that indicated the presence of one copy of ISSa4 in the genome. This fragment was present in all other patterns (D1 to D12) and was found to be specific for GBS strains with ISSa4 (Fig. 1). This observation probably indicates that the 6.5-kb HindIII fragment contains the original target site for integration of ISSa4 in the GBS genome (Fig. 1). The strain characterized by pattern D13 was isolated earlier than all other strains and could be considered to be the closely related to the original ancestor clone. The following duplications of ISSa4 in different GBS clones occurred independently and could produce other clones with various numbers of ISSa4 copies. If true, the similarity between the ISSa4 hybridization patterns (Fig. 1) can reflect the degree of genetic relationship between the strains with ISSa4. Nevertheless, this hypothesis should be confirmed in future experiments.

Identification of the target sites for ISSa4 insertions.

Previously, multiple copies of ISSa4 in the GBS genome were identified by Southern hybridization. However, the precise location in the genome was identified for only one ISSa4 copy. Insertion of this copy occurred in the cylB gene and resulted in inactivation of GBS hemolytic activity (20).

In the present study, the following strategy was chosen for identification of the target sites for insertions of ISSa4. The HindIII fragments of the chromosomal DNA were ligated into the HindIII-digested pGEM-7zf(+) cloning vector. Amplification of the ligation mixtures with primers 274 (or 275) and 106 (Table 2) produced different PCR products, some of which were isolated from agarose gels, purified, and sequenced.

The sequences of the PCR products were compared with the sequences of the complete GBS genomes (6, 22) and multiple target sites for insertions of ISSa4 were identified (Table 4). Target site 4 (Table 4) was identified inside one of the putative pathogenicity islands previously described in GBS (6, 22). Other target genes were located in different parts of the genome and insertions of ISSa4 could occur in housekeeping genes, intergenic regions, and genes for hypothetical proteins (Table 4). Most of the target regions identified were found to be strain specific (Table 4). These observations confirm the independence of the ISSa4 duplications in different GBS strains. However, the insertion of ISSa4 in the hypothetical protein (target 5) was found among 19 of 21 strains (Table 4). It probably demonstrates that this genetic event occurred at an early stage of evolution of the ISSa4-positive GBS lineage.

TABLE 4.

Target genes for ISSa4 insertions in the GBS genome

| Protein encoded by the target gene | Target AT-rich regiona | Relative location of target gene in GBS genome (22) | No. of strains with inserion of ISSa4 in gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exonuclease | AAACTCTAAATCAAAAGCT/ATATATTCTTGTA | 1747153-1747740 | 1 |

| Site-specific recombinase, phage integrase | TTTTTAATAAAAAATAGATAAT/ATATGGTACTA | 1966825-1967952 | 1 |

| Conserved hypothetical protein | ATTTTCTGTAAACGAT/AGAATTTGTAATAGTTCTTCTT TATT | 1004714-1005127 | 2 |

| Region between two hypothetical proteins | AAATTATAAATAATTAATTTCTT/TATTTTATAA | 243758-244184 | 1 |

| Hypothetical protein | ATTCACCATTGATATTATTAT/ATTTATTGTTAATA | 1969233-1969652 | 19 |

| Membrane protein, putative | TTGGAATCAAAT/TATAAGATGTGTTTTGATATT | 815147-815710 | 1 |

| Oxidoreductase, Gfo/Idh/MocA family | AATTACTAAATGTAAATTAT/AAATATTAA | 1553628-1554584 | 1 |

| Competence protein CglB | TGTACTTATTTTTAGTT/TAATATTTTATATTATTCAAAA | 188342-189190 | 1 |

| Region between hypothetical protein and rodA gene | AAAAAGTATTTTAAAAT/AGAATAAAATAAAAAAATAT | 609342-609765 | 1 |

A slash indicates the sites for insertions of ISSa4.

Previously, insertion specificity was described for some ISs in different bacterial species (13); however, little was known about transposition of the members of the IS982 family, including ISSa4. In this study, no significant similarity was observed in the sequences of the target genes for ISSa4 insertions, in the relative location of the target genes on the chromosome, or biological functions of the encoded proteins. Nevertheless, insertions of ISSa4 occurred inside AT-rich regions (Table 4), and the AT-rich regions could be considered as “hot spots” for insertions of ISSa4, as was also described for IS1 family members (15).

In summary, ISSa4-positive GBS strains belong to serotypes II and II/c and represent a specific genetic lineage characterized by the presence of IS1381 and IS861 as well as the virulence genes bac and bca. Copy number and the RFLP of ISSa4 can be effectively used for differentiation of GBS strains of serotypes II and II/c. No insertion specificity was observed for ISSa4; however, AT-rich regions could be considered as hot spots for ISSa4 insertions.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Michael Chaussee (University of South Dakota, Vermillion) and Alexander Suvorov (Institute of Experimental Medicine, Saint Petersburg, Russia) for comments that helped us publish this paper in the present form.

This work was supported by funding from the Ministry of Science and Technology, People's Republic of China, and by Russian President grant 2206.2003.4.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chatellier, S., H. Huet, S. Kenzi, A. Rosenau, P. Geslin, and R. Quentin. 1996. Genetic diversity of rRNA operons of unrelated Streptococcus agalactiae strains isolated from cerebrospinal fluid of neonates suffering from meningitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2741-2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dmitriev, A., J. V. Pak, A. N. Suvorov, and A. A. Totolian. 1997. Analysis of pathogenic group B streptococci by pulsed field gel electrophoresis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 418:351-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dmitriev, A., Y. Y. Hu, A. D. Shen, A. Suvorov, and Y. H. Yang. 2002. Chromosomal analysis of group B streptococcal clinical strains: bac gene positive strains are genetically homogenous. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 208:93-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dmitriev, A., M. Yang, E. Shakleina, L. Tkacikova, A. Suvorov, I. Mikula, and Y. H. Yang. 2003. The presence of insertion elements IS1548 and IS861 in group B streptococci. Folia Microbiol. 48:105-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis, S., M. Kotiw, and S. M. Garland. 1996. Restriction endonuclease analysis of group B streptococcal isolates from two distinct geographical regions. J. Hosp. Infect. 33:279-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glaser, P., C. Rusniok, C. Buchrieser, F. Chevalier, L. Frangeul, T. Msadek, M. Zouine, E. Couve, L. Lalioui, C. Poyart, P. Trieu-Cuot, and F. Kunst. 2002. Genome sequence of Streptococcus agalactiae, a pathogen causing invasive neonatal disease. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1499-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Granlund, M., F. Michel, and M. Norgren. 2001. Mutually exclusive distribution of IS1548 and GBSi1, an active group II intron identified in human isolates of group B streptococci. J. Bacteriol. 183:2560-2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granlund, M., L. Oberg, M. Sellin, and M. Norgren. 1998. Identification of a novel insertion element, IS1548, in group B streptococci, predominantly in strains causing endocarditis. J. Infect. Dis. 177:967-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison, L. H., J. A. Elliott, D. M. Dwyer, J. P. Libonati, P. Ferrieri, L. Billmann, A. Schuchat et al. 1998. Serotype distribution of invasive group B streptococcal isolates in Maryland: implications for vaccine formulation. J. Infect. Dis. 177:998-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauge, M., C. Jespersgaard, K. Poulsen, and M. Kilian. 1996. Population structure of Streptococcus agalactiae reveals an association between specific evolutionary lineages and putative virulence factors but not disease. Infect. Immun. 64:919-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong, F., S. Gowan, D. Martin, G. James, and G. L. Gilbert. 2002. Molecular profiles of group B streptococcal surface protein antigen genes: relationship to molecular serotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:620-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lachenauer, C. S., D. L. Kasper, J. Shimada, Y. Ichiman, H. Ohtsuka, M. Kaku, L. C. Paoletti, P. Ferrieri, and L. C. Madoff. 1999. Serotypes VI and VIII predominate among group B streptococci isolated from pregnant Japanese women. J. Infect. Dis. 179:1030-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahillon, J., and M. Chandler. 1998. Insertion sequences. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:725-774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maniatis, T., E. F. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1982. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 15.Meyer, J., S. Iida, and W. Arber. 1980. Does the insertion element IS1 transpose preferentially into A+T-rich DNA segments? Mol. Gen. Genet. 178:471-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quentin, R., H. Huet, F.-S. Wang, P. Geslin, A. Goudeau, and R. K. Selander. 1995. Characterization of Streptococcus agalactiae strains by multilocus enzyme genotype and serotype: identification of multiple virulent clone families that cause invasive neonatal disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2576-2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regan, J. A., M. A. Klebanoff, R. P. Nugent, D. A. Eschenbach, W. C. Blackwelder, Y. Lou, R. S. Gibbs, P. J. Rettig, D. H. Martin, R. Edelman et al.. 1996. Colonization with group B streptococci in pregnancy adverse outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 174:1354-1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubens, C. E., L. M. Heggen, and J. M. Kuypers. 1989. IS861, a group B streptococcal insertion sequence related to IS150 and IS3 of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 171:5531-5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuchat, A. 1998. Epidemiology of group B streptococcal disease in the United States: shifting paradigms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:497-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spellerberg, B., S. Martin, C. Franken, C. Berner, and R. Lutticken. 2000. Identification of a novel insertion sequence element in Streptococcus agalactiae. Gene 241:51-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamura, G. S., M. Herndon, J. Przekwas, C. E. Rubens, P. Ferrieri, and S. L. Hillier. 2000. Analysis of restriction fragment length polymorphisms of the insertion sequence IS1381 in group B streptococci. J. Infect. Dis. 181:364-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tettelin, H., V. Masignani, M. J. Cieslewicz, J. A. Eisen, S. Peterson, M. R. Wessels, I. T. Paulsen, K. E. Nelson, I. Margarit, T. D. Read, L. C. Madoff, A. M. Wolf, M. J. Beanan, L. M. Brinkac, S. C. Daugherty, R. T. DeBoy, A. S. Durkin, J. F. Kolonay, R. Madupu, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, N. B. Fedorova, D. Scanlan, H. Khouri, S. Mulligan, H. A. Carty, R. T. Cline, S. E. Van Aken, J. Gill, M. Scarselli, M. Mora, E. T. Iacobini, C. Brettoni, G. Galli, M. Mariani, F. Vegni, D. Maione, D. Rinaudo, R. Rappuoli, J. L. Telford, D. L. Kasper, G. Grandi, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. Complete genome sequence and comparative genomic analysis of an emerging human pathogen, serotype V Streptococcus agalactiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:12391-12396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]