Abstract

The Salmonella effector protein SopA is translocated into host cells via the SPI-1 type III secretion system (TTSS) and contributes to enteric disease. We found that the chaperone InvB binds to SopA and slightly stabilizes it in the bacterial cytosol and that it is required for its transport via the SPI-1 TTSS.

Type III secretion systems (TTSS) are found in many pathogenic gram-negative bacteria and mediate the injection of an array of effector proteins into the host cell cytoplasm. Once injected, the effector proteins modulate host cell signaling cascades for the benefit of the pathogen. The secretion mechanism of these effector proteins and their secretion signals are still poorly understood. It has been shown that secretion and translocation of many effector proteins require a cognate chaperone (9, 17). These chaperones usually bind to the N-terminal region and exert various functions on their cognate effector protein, i.e., cytosolic stability (10, 20, 21), transcriptional regulation (4, 5, 19), prevention of premature interactions (7, 12, 13), maintenance of the effector in a secretion-competent state (18, 21), and recognition by the TTSS (1). Type III secretion (TTS) chaperones do not exhibit sequence similarities but share some common features. They are generally small, acidic proteins with an amphipathic C-terminal α-helix and are often encoded next to or in close vicinity to the effector protein (9, 17). In contrast, the chaperone Spa15 of Shigella spp. is encoded within an operon encoding essential components of the TTS apparatus and binds to not just one but several effector proteins which do not show sequence similarities (16). Due to these special features, Spa15 is thought to represent a new class of TTS chaperone (16, 17).

The Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium encodes the protein InvB, which is homologous to Spa15 of Shigella spp. InvB is a chaperone for the SPI-1-encoded effector SipA/SspA (2). Recently members of our group have shown that InvB also binds to SopE and SopE2, two effector proteins encoded outside of SPI-1 but secreted in a SPI-1-dependent manner (7a). Secretion and translocation of SipA, SopE, and SopE2 depend on InvB. Based on this observation, we hypothesized that InvB might be required for secretion of additional effector proteins of serovar Typhimurium.

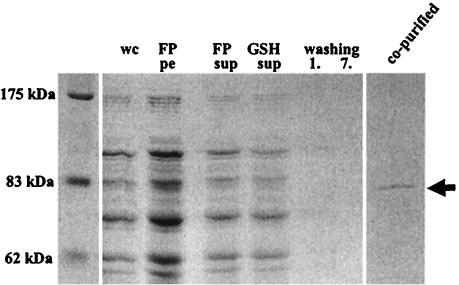

To address this question, we expressed a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-InvB fusion protein (pM672) (7a) in the mutant strain M574 (invB::aphT ΔsopE ΔsopE2 ΔsopB ΔsipA) (7a), which lacks all known InvB binding effector proteins and the chromosomally encoded invB. This strain also lacks the effector protein gene sopB. However, SopB/SigD is transported via its own cognate chaperone, PipC/SigE (6). Therefore, the sopB mutation was not expected to affect any InvB-effector protein interactions. M574 (pM672) was grown overnight in Luria broth containing 0.3 M NaCl, diluted 1:20 into fresh medium, and grown for another 4 h at 37°C (referred to as SPI-1 inducing conditions). Cells were lysed in a French pressure cell, and GST-InvB and bound proteins were purified on glutathione-Sepharose beads from the cleared cell lysate. Aliquots from every step of the purification procedure were analyzed on a Coomassie brilliant blue-stained SDS gel. A polypeptide with an apparent molecular weight of 80 kDa was copurified with GST-InvB (Fig. 1). The band was excised from the gel, trypsin digested, and eluted as described recently (7a). The protein was identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-mass spectrometry fingerprint analysis as SopA (12 matching peptides, 21% covered sequence), a known effector protein, which is encoded outside of SPI-1 but translocated in a SPI-1-dependent manner (22). Although the biochemical activity of SopA is still unknown, it was shown to play a role in bovine enterocolitis models (22, 23).

FIG. 1.

Pull-down assay to isolate InvB binding proteins. GST-InvB (34 kDa) and bound proteins were purified from cleared cell lysate by incubation with glutathione (GSH)-Sepharose beads. Bound proteins larger than the GST-InvB fusion protein were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie brilliant blue staining. wc, whole culture before harvesting of the cells; FP pe, resuspended pelleted cell debris after lysis using a French pressure cell; FP sup, cleared French pressure cell lysate; GSH sup, cleared cell lysate after binding of GST-InvB and its associated proteins; washing, supernatant after the first and seventh wash of the GSH-Sepharose beads; co-purified, GSH-Sepharose beads.

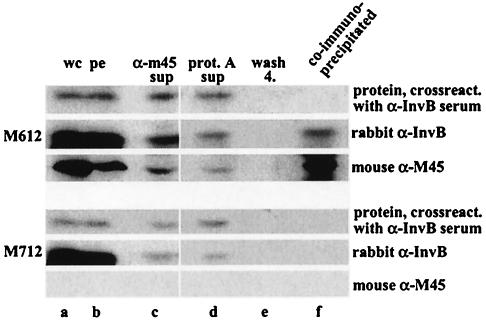

The binding of SopA to InvB was verified by a coimmunoprecipitation experiment. For this purpose, a suicide vector (pM261) encoding a C-terminally M45-tagged version of sopA was integrated into the chromosome of SL1344 to generate M612, which expresses sopAM45 under its native promoter (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and relevant markersa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Salmonella Typhimurium SL1344 strains | ||

| SL1344 | Wild type | Hoiseth and Stocker (11) |

| M574 | invB::aphT ΔsopE ΔsopE2 ΔsopB ΔsipA | Ehrbar et al. (7a) |

| M612 | sopA::pM261 | This study |

| M712 | ΔsopE ΔsopE2 ΔsopB ΔsipA ΔsopA | This study |

| Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC14028 strains | ||

| CS401 | phoN2 zxx::6251 Tn10d-Cm, Strr | Bronstein et al. (2) |

| PB502 | CS401, ΔinvB | Bronstein et al. (2) |

| M618 | PB502, sopA::pM261 | This study |

| M619 | CS401, sopA::pM261 | This study |

| M623 | CS401, sopA::pM261 invC::aphT | This study |

| M629 | CS401, sopA::pM261 spaO::aphT | This study |

| M630 | PB502, sopA::pM261 spaO::aphT | This study |

| M635 | CS401, sopA::pM265 | This study |

| M636 | PB502, sopA::pM265 | This study |

| M637 | CS401, sopA::pM265 spaO::aphT | This study |

| M638 | PB502, sopA::pM265 spaO::aphT | This study |

| M639 | CS401, sopA::pM265 invC::aphT | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pM250 | pBAD24 derivative, arabinose-inducible expression of invB (induced with 0.001% arabinose) | Ehrbar et al. (7a) |

| pM261 | pSB377 derivative, encodes the C-terminal 287 aa of sopA fused to the M45 epitope | This study |

| pM265 | pSB377 derivative, suicide vector to construct a chromosomal sopAM45 lacZ transcriptional fusion | This study |

aa, amino acids.

M612 was grown under SPI-1 inducing conditions and lysed in a French pressure cell. SopAM45 binding proteins were precipitated with a mouse monoclonal anti-M45 antibody from cleared bacterial lysates as described previously (7a). Aliquots from every step of the precipitation procedure were analyzed by Western blotting using a polyclonal anti-InvB antiserum (7a) and a mouse monoclonal anti-M45 antibody (14). InvB was coimmunoprecipitated with SopAM45 from M612 but not from the control lysate of an isogenic strain (M712) lacking amino acids 2 to 782 of sopA (Fig. 2, lane f). This result supports the notion that InvB binds (directly or indirectly) to SopA.

FIG. 2.

InvB is coimmunoprecipitated with SopAM45. A lysate of the sopAM45-expressing strain M612 (top panel) was incubated with a monoclonal mouse anti-M45 (α-M45) antibody and protein A-Sepharose beads. Samples from the precipitation procedure were analyzed by Western blotting using a polyclonal rabbit anti-InvB (α-InvB) antiserum (recognizes InvB [15 kDa] and another unidentified 18-kDa Salmonella protein) and a mouse anti-M45 antibody (recognizes SopAM45). To demonstrate specificity, a coimmunoprecipitation experiment was performed with M712 (bottom panel) (Table 1). The 18-kDa protein cross-reacting with the anti-InvB antiserum was not coprecipitated in either strain, which confirmed the specificity of the coimmunoprecipitation experiment. Lane a, whole culture before harvesting the cells (wc); lane b, resuspended bacterial pellet (pe); lane c, cleared cell lysate after incubation with anti-M45 antibody and removal of nonspecific aggregates by centrifugation (α-M45 sup); lane d, supernatant after incubation with protein A-Sepharose beads (prot. A sup); lane e, supernatant after the fourth wash of the protein A-Sepharose beads (wash 4); lane f, proteins bound to the protein A-Sepharose beads.

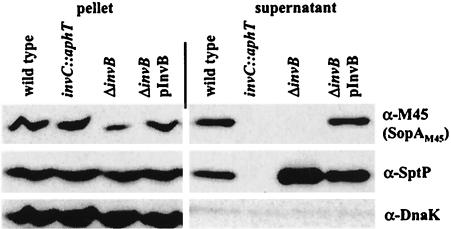

InvB has been described as a chaperone necessary for secretion of the effector proteins SipA (2), SopE, and SopE2 (7a). This suggested that InvB might also be required for secretion of SopA. To explore this hypothesis, we have constructed the isogenic serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028 strains M619 (wild type) (2), M618 (ΔinvB) (2), and M623 (invC::aphT), which all harbor an M45 epitope-tagged sopA gene in the chromosome (Table 1). The strains were grown under SPI-1 inducing conditions, and SopAM45 secretion was analyzed by Western blotting as described elsewhere (7a). SopAM45 was secreted from the wild-type strain M619 but not from the secretion-deficient strain M623 (invC::aphT), lacking the ATPase InvC (8), and the ΔinvB strain M618 (Fig. 3, upper panel). The latter secretion defect could be complemented using the invB expression vector pM250, which expresses invB under control of an arabinose-inducible promoter (7a). Reprobing with a rabbit polyclonal antiserum raised against amino acids 49 to 543 of the SPI-1 effector protein SptP verified that the invB deletion had no general effect on the TTSS (Fig. 3, middle panel).

FIG. 3.

invB-dependent expression and secretion of SopAM45. Pelleted bacteria corresponding to 300 μl of culture and proteins recovered from 2 ml of culture supernatant of strains M619 (sopAM45), M623 (sopAM45 invC::aphT), M618 (sopAM45 ΔinvB), and M618/pM250 (sopAM45 ΔinvB pInvB) were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-M45 (α-M45) antibody. The blot was reprobed with a polyclonal anti-SptP (α-SptP) antiserum to verify that a deletion of invB had no general effect on the TTSS and an anti-DnaK (α-DnaK) antiserum to confirm that the same amounts were loaded onto each lane.

The cytoplasmic SopAM45 pool was slightly lower in the ΔinvB strain M618 than in the wild-type strain, M619 (Fig. 3). This indicated that InvB might play a role in stabilization or expression of SopA. To examine the cytoplasmic stability of SopAM45, one has to consider that InvB might have two functions: stabilization of cytoplasmic SopA and transport of SopA via the SPI-1 TTSS. If significant amounts of SopA protein become transported to the outside during the course of the assay, this fraction might become protected from degradation by Salmonella proteases. To exclude this, we have analyzed the role of invB in stabilization of cytoplasmic SopAM45 in secretion-deficient strains. The invB open reading frame is overlapping with the invC open reading frame. Therefore, it was not possible to combine the ΔinvB and invC::aphT alleles (Fig. 3; Table 1) by P22 transduction. For this reason we constructed the secretion-deficient spaO::aphT strain (M629), lacking an essential subunit of the export apparatus (3) encoded 2.7 kb downstream of invB, and the ΔinvB spaO::aphT double mutant (M630).

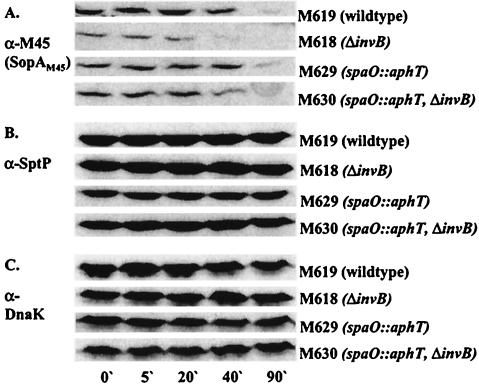

We then analyzed the cytosolic stability of SopAM45 in the ΔinvB strain M618 (sopAM45 ΔinvB; does not secrete SopAM45 [Fig. 3]), the secretion-deficient mutant M629 (sopAM45 spaO::aphT), and the double mutant M630 (sopAM45 spaO::aphT ΔinvB) (Table 1). As a control we also examined the cytosolic stability of SopAM45 in the wild-type strain M619 (sopAM45). M619, M618, M629, and M630 were grown under SPI-1 inducing conditions, and protein biosynthesis was inhibited by addition of spectinomycin (final concentration, 200 μg/ml). Aliquots were removed 0, 5, 20, 40, and 90 min after spectinomycin addition. Western blot analysis of bacterial pellets revealed that SopAM45 degradation was slightly accelerated in the absence of InvB (Fig. 4A, compare M629 and M630 or M618 and M629). In the wild-type strain background (M619), the amount of bacterium-associated SopAM45 was slightly higher than in the secretion-deficient strain M629 at the beginning of the experiment (0′ to 20′) but decreased faster (Fig. 4A). As discussed above, this is probably due to cumulative effects of secretion of SopAM45 from M619 into the culture supernatant and degradation. For this reason we could not base any conclusions about the role of InvB in SopA stabilization on this strain.

FIG. 4.

Effect of an invB deletion on the stability of SopAM45. Amounts of cytosolic SopAM45 at different time points after addition of spectinomycin were analyzed by Western blotting using a mouse anti-M45 (α-M45) and polyclonal rabbit anti-SptP (α-SptP) to verify that a deletion of invB had no general effect on the stability of effectors. To ensure equal loading of the lanes, the blot was reprobed using an anti-DnaK (α-DnaK) antibody.

The stability of the effector protein SptP (cognate chaperone is SicP) was not affected by the invB mutation (Fig. 4). Altogether, these data suggested that InvB has a slight effect on stabilization of SopA in the bacterial cytosol.

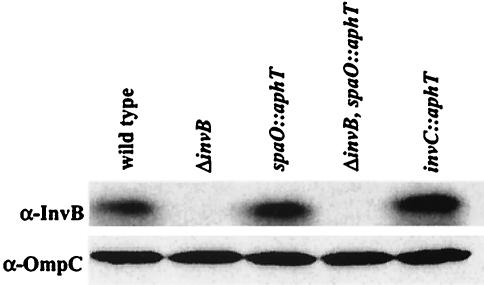

To verify that the invB expression level is not altered in the secretion-deficient mutants, we performed a Western blot analysis using the strains M619 (sopAM45), M618 (sopAM45 ΔinvB), M629 (sopAM45 spaO::aphT), M630 (sopAM45 spaO::aphT ΔinvB), and M623 (sopAM45 invC::aphT) (Table 1). This analysis confirmed that the amount of cytosolic InvB is not altered in the secretion-deficient mutants M629 (sopAM45 spaO::aphT) and M623 (sopAM45 invC::aphT) and that InvB is absent from the invB deletion strains M618 (sopAM45 ΔinvB) and (sopAM45 spaO::aphT ΔinvB) (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Western blot analysis of invB expression level. Bacteria were grown under SPI-1 inducing conditions. Bacteria recovered from 200 μl of culture of strains M619 (sopAM45), M618 (sopAM45, ΔinvB), M629 (sopAM45 spaO::aphT), M630 (sopAM45 ΔinvB spaO::aphT), and M623 (sopAM45 invC::aphT) were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-InvB antiserum (α-InvB). The blot was reprobed with a monoclonal anti-OmpC antibody (α-OmpC) to verify that equivalent amounts of lysate were loaded onto each lane.

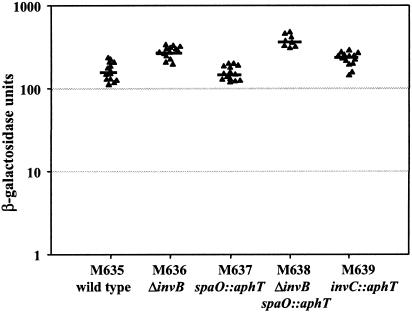

To analyze whether invB reduces transcription of sopA, we constructed lacZ transcriptional reporter strains. The lacZ cassette of pSB1040 (kindly provided by D. Zhou and J. E. Galán) was cloned downstream of the sopAM45 stop codon into pM261 (see above) to create the suicide vector pM265 (Table 1). pM265 was integrated into the chromosome of CS401, yielding M635 (sopAM45 lacZ). The control strains M636 (ΔinvB), M637 (spaO::aphT), M638 (ΔinvB spaO::aphT), and M639 (invC::aphT) were constructed by P22 transduction of the sopA::pM265 allele (Table 1).

Thus, we could use β-galactosidase assays to study sopA promoter activity. The β-galactosidase activity was determined in at least eight independent experiments, and statistical analysis was performed using the exact Mann-Whitney U test. We found that sopA transcription was in the same order of magnitude for all strains, analyzed (Fig. 6). Disruption of invB did not decrease β-galactosidase activity. Rather, β-galactosidase activity was slightly but significantly increased in M636 (ΔinvB) (P < 0.001), M639 (invC::aphT) (P = 0.001), and M638 (ΔinvB spaO::aphT) (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6). Therefore, the decreased SopAM45 protein levels in the cytoplasm of an invB mutant (Fig. 3) are attributable to a slightly decreased protein stability but not to transcriptional down regulation. However, the reasons for the slight augmentation of transcription in M636, M638, and M639 remain to be analyzed.

FIG. 6.

Effect of an invB deletion on transcription of sopAM45. Transcription of sopAM45 was measured using transcriptional lacZ reporter constructs in standard β-galactosidase activity assays. β-Galactosidase activities were determined in at least eight independent experiments. Bars indicate the median.

In summary, the copurification and coimmunoprecipitation experiments demonstrate that InvB binds directly or indirectly to SopA. In the absence of InvB, SopA is not secreted and its intracellular stability is decreased. Although SipA, SopE/SopE2, and SopA do not share sequence similarities, they all require InvB for their transport via the SPI-1 TTSS (2, 7a; also this study).

TTS chaperones have been divided into three classes: class I, chaperones which associate with effector proteins; class II, chaperones which associate with translocators; and class III, chaperones of the flagellar system (17). Due to their unique features, InvB and its homologs Spa15 (Shigella spp.), YsaK (Yersinia spp.), and InvB (Sodalis spp.) are thought to represent a new family of TTS chaperones. Therefore, they have been assigned to the new subclass IB, which represents chaperones that bind several different effectors (17). This classification was based on experimental evidence from Shigella flexneri (16). Interestingly, Page and Parsot have hypothesized that InvB, like Spa15, might also associate with different unrelated proteins (15). This was confirmed by our findings that InvB is a chaperone not only for SipA (2) but also for SopE, SopE2 (7a), and SopA (this work).

Acknowledgments

We thank Günther Paesold, Markus Schlumberger, and Cosima Pelludat for critically reviewing the manuscript, Samuel I. Miller for providing strains, Shiva P. Singh for providing the anti-OmpC antibody, and Rene Brunisholz for the matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-mass spectrometry analysis.

The project was funded in part by the Swiss National Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Birtalan, S. C., R. M. Phillips, and P. Ghosh. 2002. Three-dimensional secretion signals in chaperone-effector complexes of bacterial pathogens. Mol. Cell 9:971-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bronstein, P. A., E. A. Miao, and S. I. Miller. 2000. InvB is a type III secretion chaperone specific for SspA. J. Bacteriol. 182:6638-6644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collazo, C. M., and J. E. Galan. 1996. Requirement for exported proteins in secretion through the invasion-associated type III system of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 64:3524-3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darwin, K. H., and V. L. Miller. 2000. The putative invasion protein chaperone SicA acts together with InvF to activate the expression of Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes. Mol. Microbiol. 35:949-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darwin, K. H., and V. L. Miller. 2001. Type III secretion chaperone-dependent regulation: activation of virulence genes by SicA and InvF in Salmonella typhimurium. EMBO J. 20:1850-1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darwin, K. H., L. S. Robinson, and V. L. Miller. 2001. SigE is a chaperone for the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium invasion protein SigD. J. Bacteriol. 183:1452-1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day, J. B., I. Guller, and G. V. Plano. 2000. Yersinia pestis YscG protein is a Syc-like chaperone that directly binds yscE. Infect. Immun. 68:6466-6471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Ehrbar, K., A. Friebel, S. I. Miller, and W. D. Hardt. 2003. Role of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) protein InvB in type III secretion of SopE and SopE2, two Salmonella effector proteins encoded outside of SPI-1. J. Bacteriol. 185:6950-6967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Eichelberg, K., C. C. Ginocchio, and J. E. Galan. 1994. Molecular and functional characterization of the Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes invB and invC: homology of InvC to the F0F1 ATPase family of proteins. J. Bacteriol. 176:4501-4510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman, M. F., and G. R. Cornelis. 2003. The multitalented type III chaperones: all you can do with 15 kDa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 219:151-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu, Y., and J. E. Galan. 1998. Identification of a specific chaperone for SptP, a substrate of the centisome 63 type III secretion system of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 180:3393-3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoiseth, S. K., and B. A. Stocker. 1981. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature 291:238-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menard, R., P. Sansonetti, C. Parsot, and T. Vasselon. 1994. Extracellular association and cytoplasmic partitioning of the IpaB and IpaC invasins of S. flexneri. Cell 79:515-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neyt, C., and G. R. Cornelis. 1999. Role of SycD, the chaperone of the Yersinia Yop translocators YopB and YopD. Mol. Microbiol. 31:143-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obert, S., R. J. O'Connor, S. Schmid, and P. Hearing. 1994. The adenovirus E4-6/7 protein transactivates the E2 promoter by inducing dimerization of a heteromeric E2F complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:1333-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page, A. L., and C. Parsot. 2002. Chaperones of the type III secretion pathway: jacks of all trades. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Page, A. L., P. Sansonetti, and C. Parsot. 2002. Spa15 of Shigella flexneri, a third type of chaperone in the type III secretion pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1533-1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parsot, C., C. Hamiaux, and A. L. Page. 2003. The various and varying roles of specific chaperones in type III secretion systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:7-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stebbins, C. E., and J. E. Galan. 2001. Maintenance of an unfolded polypeptide by a cognate chaperone in bacterial type III secretion. Nature 414:77-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tucker, S. C., and J. E. Galan. 2000. Complex function for SicA, a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium type III secretion-associated chaperone. J. Bacteriol. 182:2262-2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wattiau, P., B. Bernier, P. Deslee, T. Michiels, and G. R. Cornelis. 1994. Individual chaperones required for Yop secretion by Yersinia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:10493-10497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wattiau, P., and G. R. Cornelis. 1993. SycE, a chaperone-like protein of Yersinia enterocolitica involved in Ohe secretion of YopE. Mol. Microbiol. 8:123-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood, M. W., M. A. Jones, P. R. Watson, A. M. Siber, B. A. McCormick, S. Hedges, R. Rosquist, T. S. Wallis, and E. E. Galyov. 2000. The secreted effector protein of Salmonella dublin, SopA, is translocated into eukaryotic cells and influences the induction of enteritidis. Cell. Microbiol. 2:293-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang, S., R. L. Santos, R. M. Tsolis, S. Stender, W. D. Hardt, A. J. Baumler, and L. G. Adams. 2002. The Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium effector proteins SipA, SopA, SopB, SopD, and SopE2 act in concert to induce diarrhea in calves. Infect. Immun. 70:3843-3855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]