Abstract

Objective

To identify GPs' attitudes towards sickness certification.

Design

Systematic search and narrative review identifying themes around attitudes towards sickness certification.

Results

Eighteen papers were identified for inclusion in the review; these included qualitative, quantitative, and systematic reviews. The papers were predominantly from Scandinavia and the UK. Three themes were identified from the literature: conflict, role responsibility, and barriers to good practice. Conflict was predominantly centred on conflict between GP and patients regarding the need for a certificate, but there was also conflict between all stakeholders. Role responsibility focused on the multiple roles GPs had to fulfil, and barriers to good practice were identified both within and outside the healthcare system.

Conclusion

Any potential for changing the certification system needs to focus on reducing the potential for conflict, clarification of the roles of all stakeholders, and improving access to specialist occupational health and rehabilitation services.

Key Words: Family practice, general practice, primary care, sickness certification, systematic review, work absence

Work is generally good for our health and well-being, and absence from work is generally detrimental [1]. Absence from work is typically sanctioned by general practitioners (GPs) who issue sickness certificates stating whether a patient requires time off work and for how long work absence is advised.

There is a relationship between an individual's beliefs and his/her behaviour. This is demonstrated in the advice GPs and other healthcare practitioners give back pain patients about returning to or remaining at work [2–5]. If attitudes and beliefs influence the advice given to patients about remaining at work, it is likely that attitudes and beliefs towards sickness certification will influence the way in which a GP issues certificates. Haldorsen et al. [6] identified a number of factors that influence a GP's decision-making process in relation to sickness certification, including past experience, education, individual clinical reasoning, knowledge of the evidence base, personal beliefs, and time. How these factors impact upon the decision to issue sickness certificates needs further exploration. Alexanderson and Norlund [7] reported that few studies had addressed attitudes to sickness absence or the “absence culture” and this remains an area where further research should be focussed.

Although GPs are the gatekeepers to statutory sick pay through sickness certification in the majority of European countries, little is known about how GPs view the sickness certification process or the reasoning behind their decision to issue a sickness certificate. With little understanding of GPs' attitudes towards sickness certification, any proposed changes in the way certificates are issued is unlikely to address the needs of the GP, the patient, or the employer in this complex decision-making process.

Aim

The aim of this study is to systematically review the literature reporting GPs' attitudes towards sickness certification.

Material and methods

Search strategy

Systematic searches of online electronic bibliographies (AHMED, CINAHL, DHData, EMBASE, Kingsfund, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, CSA Illumina) were conducted. Databases were searched from their inception until January 2010. The search strategy is available from the authors on request. The reference lists of each identified paper were also searched for further literature. The search strategy was developed with clinicians (general practice and nursing) and epidemiologists experienced in literature searching and systematic reviewing. All available abstracts from the European Public Health Association (EUPHA) were also reviewed (from the year 2006), as were all listed publications by the Department for Work and Pensions and the Department of Health.

Study selection

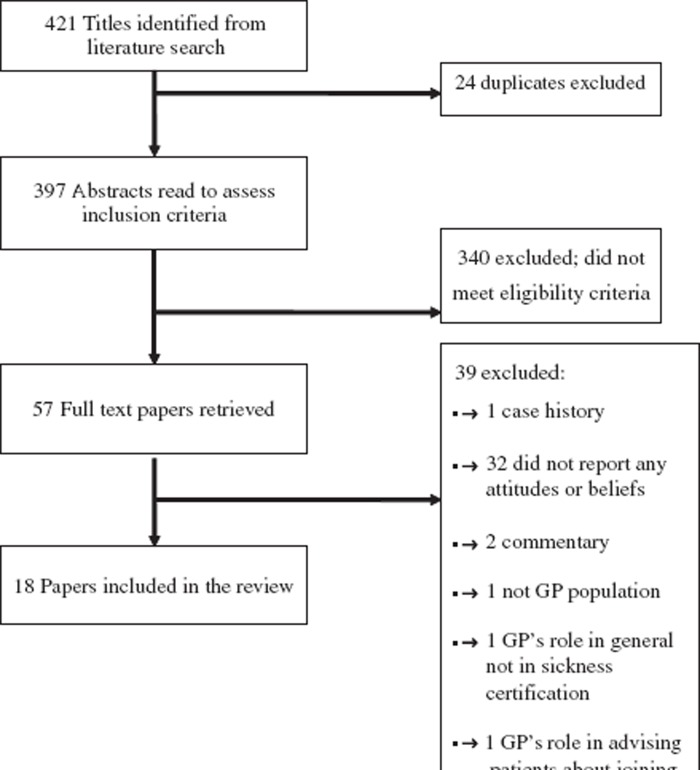

The titles of all studies identified from the search strategy were screened and those clearly not meeting the inclusion criteria were excluded at this stage. The abstracts and full texts of the remaining studies were then appraised by two reviewers to assess eligibility (GW-J & CDM); those not meeting the inclusion criteria at this stage were excluded. The full texts of the remaining papers were then obtained and again reviewed independently to assess eligibility. Figure 1 shows the identified papers from the search to inclusion in the review.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the results from the systematic search and selection of studies.

To be included in the review, studies had to be conducted in primary care and participants had to be clinically active general practitioners. Studies had to report an attitude towards sickness certification through the expression of an opinion on the certification process and/or a belief about sickness certification. Attitudes and beliefs could be obtained from specific questions or elicited through interviews or focus groups; therefore there was no restriction on the study design included in the review. Due to the heterogeneity of the methods and the presentation of results, a narrative review was conducted. Two authors reviewed each paper and developed a coding schedule based on the themes emerging from the identified papers; these codes were then collapsed into categories to allow the papers to be compared and reported.

Results

The search yielded 397 unique papers. Of the 397 articles 340 were excluded through review of the abstracts. Full texts of the remaining 57 papers were obtained. A further 39 of these articles were excluded as they did not meet the eligibility criteria, leaving 18 articles that included information on GPs' attitudes towards sickness certification (see Figure 1).

Seven papers used quantitative methods, eight qualitative methods, two mixed methods, and one systematic review. The majority of papers were from Scandinavia (Sweden and Norway), with a further five originating in the UK and one from Switzerland (Table I). Three main themes were identified within the papers: conflict, role responsibility, and barriers to good practice. The summary of findings will be presented within these themes. The majority of papers reported findings in more than one theme (Table I).

Table I.

Identified studies and their characteristics

| Study | Country | Study type | Population | Themes | Sub-themes |

| Arrelöv et al. (2007) [8] | Sweden | Quantitative | 673 GPs 149 Orthopaedic surgeons | Conflict | Handling certification is problematic on a weekly basis |

| Meershoek et al. (2007) [9] | Netherlands | Qualitative – ethnographic study | 20 doctors employed full time in sickness certification | Conflict | Account of personal circumstances Efforts to return to work Patient's view of the complaint |

| Role responsibility | Assessment of consequences for patient | ||||

| Hiscock & Ritchie (2001) [10] | UK | Qualitative | In-depth interviews with 33 GPs and five discussion groups | Conflict | Patient conflict, threat of litigation |

| Role responsibility | Preference for no role in certification/value the role Managing RTW Judging incapacity for work Independent assessment for certification |

||||

| Holdsworth et al. (2008) [23] | UK | Quantitative (with open questions) | 64 physiotherapists and 97GPs with experience of self-referral to physiotherapy | Role responsibility | Benefits of certification by other professionals |

| Swartling et al. (2008) [11] | Sweden | Qualitative interviews | 19 GPs | Conflict | Demanding patients Solution to non-medical problems |

| Barriers to good practice | Other health professions initiating certification Health system deficiencies Societal attitudes to sick listing |

||||

| Bollag et al. (2007) [24] | Switzerland | Mixed methods | Sickness certificates identified from the Swiss Sentinel Surveillance network. Physicians completed a questionnaire (78) | Role responsibility | Positive and negative aspects of certification |

| Barriers to good practice | Suggested changes to the system | ||||

| Breen et al. (2006) [12] | UK | Qualitative | 21 GPs took part in telephone interviews | Conflict | Negotiating with patient & patient agenda |

| Barriers to good practice | Employer attitudes | ||||

| Campbell & Ogden (2006) [13] | UK | Quantitative | Questionnaire-based vignettes (829 GPs) | Role responsibility | Responsibility to issue certificates – linked to feelings of sympathy for the patient |

| Conflict | Patient demand & family circumstances did not influence decision | ||||

| Hussey et al. (2003) [14] | UK | Qualitative | Qualitative focus groups with 67 GPs (11 groups) | Conflict | Conflict of interest Dr/pt relationship Felt undermined and undervalued by colleagues |

| Role responsibility | Felt ill used by stakeholders' demands and expectations | ||||

| Barriers to good practice | Responsibility to patient versus DWP/DSS Patients' lives would be better if they were able to work Extension of self-certification Need for a referral system Better occupational health and rehabilitation Further training in certification |

||||

| Wahlström & Alexanderson (2004) [15] | Sweden | Systematic review | Systematic review of physicians' sick-listing practices | Role responsibility | Legitimizing back painPatient advocate role |

| Barriers to good practice | Lack of knowledge about the patient, the labour market & social insurance laws | ||||

| Conflict | Attitudes of patients Patient influences | ||||

| Swartling et al. (2007) [17] | Sweden | Quantitative | Questionnaire of 3997 physicians | Conflict | Felt threatened by patients Support from management Fear of being reported to disciplinary board |

| Role responsibility | “Double role” as patient's doctor and medical expert for the social insurance office | ||||

| Englund et al. (2000) [18] | Sweden | Quantitative | Case vignettes were sent to 360 GPs who were asked to complete a certificate for each vignette | Conflict | Trend to sick list demanding cases |

| Swartling et al. (2007) [16] | Sweden | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews with 19 GPs | Role responsibility | Type of approach to certification in terms of responsibility and understanding |

| Conflict | Between society & patient | ||||

| Von Knorring et al. (2008) [19] | Sweden | Qualitative | Qualitative study of 26 physicians | Barriers to good practice | Insurance system, organization of healthcare Lack of knowledge of the consequences of certification |

| Conflict | Hidden agendas No one in charge |

||||

| Role responsibility | With others in the system/ stakeholders/patients Difficulty in handling the various roles of the GP Aware of poor practice leading to despair |

||||

| Löfgren et al. (2007) [20] | Sweden | Quantitative | Cross-sectional questionnaire study (4019 physicians) | Conflict | Between patient & GP |

| Role responsibility | Deciding whether to extend the period of certification | ||||

| Krohne & Brage (2007) [21] | Norway | Qualitative | Focus groups | Conflict | Communication with employers/insurance office Difficulty separating health information and functional information – linked to confidentiality |

| Barriers to good practice | Have faith in the patient or your own assessment | ||||

| Role responsibility | It's not my field of expertise Not an important component of the GP's job | ||||

| Tellnes et al. (1990) [22] | Norway | Quantitative | 107 GPs issuing certificates over a four-week period in 1985 | Barriers to good practice | Certification should be allowed on social grounds Personal examination should take place |

| Conflict | Telephone consultation should be acceptable Certification of unemployed patients Pts wish should be the deciding factors |

||||

| Engblom et al. (2009) [25] | Sweden | Qualitative | 195 case reports written by 195 physicians | Role responsibility | Feeling uncomfortable with handling cases where life events & mental problems were involved |

Note: RTW = return to work.

Conflict

Conflict was a common theme and was reported in 14 of the papers [8–22]. The most common conflict was between the patient and doctor, but there were also conflicts between other stakeholders and the doctor.

A third of GPs reported sickness certification to be problematic [20], with many GPs reporting that handling of sickness certification was problematic on a weekly basis [8]. Half of GPs found handling disagreements with patients, decisions about the prolongation of certification, assessing patients' work ability, and optimum duration of sickness certification fairly or very problematic [20]. Furthermore many GPs felt threatened by patients at least once every month [17].

The demanding of a sickness certificate by patients was a common cause of conflict in the consultation. It has been reported that a patient demanding a certificate is particularly difficult when it opposes the GP's own judgement but denying a certificate is not possible in the situation concerned [11]. GPs undertake a negotiation with patients; ascertaining the patient's expectations and being able to manage them was key in this negotiation and in managing the potential for conflict [12]. Patients' demands for sickness certificates do not necessarily influence a GP's decision to issue one; this decision is based principally on the patient's health and also his/her family circumstances [13]. However, some GPs report that they were more likely to issue sickness certificates to those patients who were demanding of them [18], with GPs feeling that the patient's wish should be the deciding factor in issuing a sickness certificate [22].

Many GPs believed that people always have complaints, but questioned whether these complaints were covered by the clinical diagnosis and whether or not this was relevant when making a social medical judgement [9]. GPs also believed that they should not formally take into account private circumstances when issuing sickness certificates, but if patients were questioned too much the conflict would become worse [9]. However, some GPs' attitude towards patients was positive, stating that patients' efforts to recover and return to work implied that they did not want to take advantage of the system, and that they wanted to generate the GP's trust and were telling the truth about their problems [9]. GPs believed the difficulties in assessing risk to health through return to work was a source of conflict, feeling that they were unable to tell patients that they felt their symptoms were not genuine [10]. The consequence of GPs believing that they were unable to comment on the legitimacy of symptoms was the GPs' perception of a threat of litigation [10]. This fear of litigation or reprimand was frequent in general practice with one in 10 GPs feeling worried about being reported to the disciplinary board [17].

Several studies indicated that the potential for conflict was not solely with the patient, but also included conflict with other clinical colleagues and stakeholders. GPs indicated a feeling of being undermined and undervalued by secondary care colleagues and other health and social services, in particular where colleagues who could certify delegated this role to the GP [14]. Some GPs felt that secondary care doctors were “dumping” cases who needed sickness certificates onto them [19]. Healthcare professionals other than GPs demanding sickness certificates were also identified as a source of conflict [19]. Difficulties and conflicts arising in communication with employers or insurance offices were raised. In particular, the distinction between providing information about a patient's health and functional ability represented a possible breach of patient–doctor confidentiality [21]. In contrast, support from management was identified as a positive experience; good support was associated with a lower risk of experiencing threats and worries concerning the certification process [17]. Lastly, a broader view of conflict focusing on the conflict between the interests of society and patients has been reported, with GPs stating that “it must be possible to adapt jobs to the individual rather than the opposite” [16].

Role responsibility

Role responsibility was a theme reported in 13 papers[9,10,13–17,19–21,23–25], and centred on the management of the many roles and responsibilities that GPs have towards their patients, the state, and society.

Many of the papers reported that GPs often found that their roles in the sickness certification process were unclear and conflicting. Responsibility towards the patients and the UK Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) and the Department of Social Security (DSS) generated some divergence when making the decision to issue a sickness certificate [14]. However, the majority of participants in this study felt their responsibility to their patients outweighed that to the DWP or DSS [14]. This difficulty in handling the various roles that the GPs play leads to concerns about poor practice and despair in the process as a whole, and the GP's role in particular [19]. It has been suggested that older and more established GPs are more likely to issue sickness certificates, as they have an established relationship with their patients which they are unwilling to threaten by refusing to issue a sickness certificate [14]. It was also suggested that older GPs had a more positive view of sickness certification than younger GPs [15].

It has been suggested that GPs have a “dual role” as the patient's doctor and also the medical expert for the social insurance office [17,19]. This dual role involved acting as patient advocate, medical expert, and gatekeeper, leading to GPs reporting difficulty in handling these conflicting roles [19]. Particular discomfort with their sick-listing role occurred when the patient reported deaths in the family or other stressful life events, or mental disorders or alcohol consumption were involved [25]. The difficulty of managing the dual role could lead to conflict between the patient and physician [17].

The issue of conflicting responsibilities has been examined using a qualitative approach to elicit five different methods that GPs use to address the issue of divided responsibilities in relation to sickness certification [16]. Responsibility for certification ran along a continuum starting with GPs being very passive players in the certification process, where they feel that they have no responsibility for the patient's rehabilitation, to an empowering approach where the patient is fully encouraged to take responsibility for his/her own sickness certification and rehabilitation [16].

There was a strong feeling throughout the literature that GPs had a clear and primary responsibility to their patients. There was some consideration by GPs of the consequences of sickness certification, particularly in light of the patients' long-term possibilities in the labour market [9]. GPs often made value judgements regarding patients' lives, believing that they would be better if they were able to work, with one GP reporting that early return to work was better for the patient but the employer's benefit was not a concern for them [14]. This difficulty in managing the return to work process and judging incapacity for work also raised concerns about the GP's role in the certification process, with many GPs reporting that they would prefer no role in the sickness certification process at all [10]. GPs suggested that there may be benefits in sickness certification being taken on by other health professionals [23]. Some GPs reported that they would give up their role in sickness certification [14], whilst others felt that certification was not an important part of their job [21].

A systematic review of sickness certification practices found that GPs were concerned about legitimizing the sick role, particularly in patients with back pain [15]. Wishing to prevent the development of a sick role was associated with difficulties in making a decision to extend a sickness certificate, particularly one that had initially been issued by another GP, and ascertaining the optimum duration and degree of sickness certification [20].

Although the majority of GPs reported conflict in certification some also reported positive aspects. In particular GPs stated that it was a core function and enabled them to preserve the confidentiality of the patient's health problem, protected them from allegations by the workplace and may have therapeutic implications [24]. Furthermore, GPs felt that being familiar with the patient's antecedents meant that they were the most appropriate healthcare professionals to assess capacity for work [24].

Barriers to good practice

Barriers to good practice were reported in nine papers [11,12,14,15,19–22,24] and ranged from difficulties with individual patients to difficulties with the sickness certification system as a whole.

Barriers to good practice have been classified as either within or outside healthcare [11]. Barriers to good practice within healthcare systems focussed on the GPs' own competence in certification decisions, in particular judging incapacity for work and the duration of absence required. It was suggested that although certification should be based on physical health, allowing certification on social grounds would improve practice and reduce some of the perceived conflict within the consultation [22]. This was compounded by conflicting advice from other health professionals who suggest to patients that they need to be absent from work when the GP does not agree [11]. Difficulties working with other colleagues were identified as barriers to practice, with GPs feeling undermined by hospital and other colleagues. This is also related to conflict in the certification process [14]. Furthermore, a large number of GPs would prefer not to be part of the sickness certification system, suggesting the alternative of an authoritative individual to whom they could refer patients [14]. An alternative was the availability of an authoritative agency or professional for delegation of complex cases only [24].

A lack of collaboration from other stakeholders was identified as problematic in sickness certification. In particular employers, social insurance, unemployment, and social welfare groups were considered to be slow, passive, and difficult to contact and either under-resourced or using resources inappropriately [11]. Changes to the sickness certification system that GPs felt would improve their ability to issue appropriate certificates have been suggested [24]. These changes addressed some of the barriers to good certification practice that have been identified in this review, such as changing employers' and employees' attitudes towards absenteeism and the development of a healthy working environment [24]. However, the engagement of employers in the management of absence and sickness certification was also identified as a barrier to good practice [12]. It was reported that employers have to have a very positive attitude towards getting employees back to work, and many of them are happy to continue full pay for as long as it takes, which the GPs felt was not an appropriate attitude to adopt [12]. In addition to lack of cooperation from other stakeholders, particular difficulties with employers, unemployment offices and the social welfare office were specifically mentioned [19]. Communication was reported to be a specific problem, particularly when employers are contacting the GP; this is related to role responsibility [21].

Deficiencies in the healthcare system such as time constraints in the consultation and long referral times to rehabilitation services also introduced barriers to good practice [11]. The extension of the self-certification period would be an alternative to GPs writing certificates and was suggested by some GPs [14,24]. Additional changes suggested were better provision of occupational health and rehabilitation, with further training for GPs and the establishment of clinics to address sickness certification [14]. However, there was a lack of knowledge regarding the labour market and social insurance laws, again creating barriers to good practice [15]; this issue could be linked to the training gap identified previously. There was a concern amongst some GPs that there may have been a hidden agenda, with politicians attempting to hide unemployment using the sickness certification system. Furthermore, procedures in certification were reported to be lacking, counterproductive, or inadequate concerning policy and support [19].

Discussion

Summary of main findings

This review has identified three themes related to GPs' attitudes and beliefs towards sickness certification: conflict, role responsibility, and barriers to good practice. Conflict was identified in the majority of papers and was focused on two areas: conflict with patients and conflict with other stakeholders. Role responsibility was centred on conflicting responsibilities, in particular being responsible to the patient and also to the social security department with concerns about a “dual role” of GPs. The final theme identified from the literature addressed barriers to good practice. These barriers were related to management of patients with sickness certificates and also to functioning within the sickness certification system.

Strengths and limitations

The limitation of carrying out a review of this nature is the non-standardized information reported in papers. Many report qualitative data and there are potential issues in the interpretation of data. However, by grouping information into themes, the potential bias that could arise though secondary interpretation should be minimized. Second, we did not carry out a quality appraisal of the papers included in the review. A number of quality appraisal instruments would have been required to address the differing study types, and comparison between them would then be meaningless. The strength of this review is the inclusive nature of the analysis; papers were not excluded based on quality, meaning all papers could provide data. The inclusion of both quantitative and qualitative data ensures that all the available evidence is appraised rather then just one method, providing a broader view. The themes identified in each paper were coded by one researcher (GW-J) and fed back to the other authors where a large degree of agreement was found. The authors of this paper were from very different backgrounds and included a GP to ensure that the themes identified were relevant to practicing clinicians.

Implications

There has been much debate in the UK regarding sickness certification and methods to improve or alter the system [26,27]. In order to make changes that are going to work in practice, the attitudes and beliefs of the GPs need to be taken into account. By identifying those issues that are the most problematic to GPs, any changes that are planned to the system can incorporate strategies to tackle these issues and facilitate the sickness certification process for those that are on the front line of the sickness certification system.

Conclusions

The beliefs of all stakeholders in the sickness certification process need to be challenged to move away from the sick role and adopt a more positive approach to health and work. However, if challenges are to be met then the support to meet these challenges also needs to be provided. This support needs to focus on reducing the potential for conflict, clarification of stakeholder roles, and tackling barriers to good practice.

Source of funding

North Staffordshire Medical Institute funded this study.

KMD is funded through a Research Career Development Fellowship from the Wellcome Trust [083572].

CDM is funded by an ARC Career Development Fellowship.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Waddell G, Burton AK. Is work good for your health and wellbeing? London: TSO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fullen BM, Baxter GD, O'Donovan BG, Doody C, Daly L, Hurley DA. Doctors' attitudes and beliefs regarding acute low back pain management: A systematic review. Pain. 2008;136:388–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop A, Foster NE, Thomas E, Hay EM. How does the self-reported clinical management of patients with low back pain relate to the attitudes and beliefs of health care practitioners? A survey of UK general practitioners and physiotherapists. Pain. 2008;135:3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bishop A, Thomas E, Foster NE. Health care practitioners' attitudes and beliefs about low back pain: A systematic search and critical review of available measurement tools. Pain. 2007;132:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coudeyre E, Rannou F, Tubach F, Baron G, Coriat F, Brin S, et al. General practitioners' fear-avoidance beliefs influence their management of patients with low back pain. Pain. 2006;124:330–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haland H, Brage S, Stromme J, Tellnes G, Ursin H. Musculoskeletal pain: Concepts of disease, illness, and sickness certification in health professionals in Norway. Scand J Rheumatol. 1996;25:224–32. doi: 10.3109/03009749609069991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexanderson K, Norlund A. Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU). Chapter 12: Future need for research. Scand J Public Health. 2004;63((Suppl)):256–8. doi: 10.1080/14034950410021925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arrelov B, Alexanderson K, Hagberg J, Loefgren A, Nilsson G, Ponzer S. Dealing with sickness certification: A survey of problems and strategies among general practitioners and orthopaedic surgeons. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:273. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meershoek A, Krumeich A, Vos R. Judging without criteria? Sickness certification in Dutch disability schemes. Sociol Health Illness. 2007;29:497–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiscock J, Ritchie J. The role of GPs in sickness certification. Leeds: HMSO; 2001. Report No. 148. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swartling MS, Alexanderson KAE, Wahlstrom RA. Barriers to good sickness certification: An interview study with Swedish general practitioners. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36:408–14. doi: 10.1177/1403494808090903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breen A, Austin H, Campion-Smith C, Carr E, Mann E. “You feel so hopeless”: A qualitative study of GP management of acute back pain. Eur J Pain. 2007;11:21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell A, Ogden J. Why do doctors issue sick notes? An experimental questionnaire study in primary care. Fam Pract. 2006;23:125–30. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussey S, Hoddinott P, Wilson P, Dowell J, Barbour R. Sickness certification system in the United Kingdom: Qualitative study of views of general practitioners in Scotland. Br Med J. 2004;328:88. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37949.656389.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wahlstrom R, Alexanderson K. Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU). Chapter 11. Physicians' sick-listing practices. Scand J Public Health. 2004;63((Suppl)):222–55. doi: 10.1080/14034950410021916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swartling M, Peterson S, Wahlstrom R. Views on sick-listing practice among Swedish General Practitioners: A phenomenographic study. Bmc Fam Pract. 2007;8 doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swartling MS, Hagberg J, Alexanderson K, Wahlstrorm RA. Sick-listing as a psychosocial work problem: A survey of 3997 Swedish physicians. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17:398–408. doi: 10.1007/s10926-007-9090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Englund L, Tibblin G, Svardsudd K. Variations in sick-listing practice among male and female physicians of different specialities based on case vignettes. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2000;18:48–52. doi: 10.1080/02813430050202569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Von Knorring M, Sundberg L, Lofgren A, Alexanderson K. Problems in sickness certification of patients: A qualitative study on views of 26 physicians in Sweden. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2008;26:22–8. doi: 10.1080/02813430701747695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lofgren A, Hagberg J, Arrelov B, Ponzer S, Alexanderson K. Frequency and nature of problems associated with sickness certification tasks: A cross-sectional questionnaire study of 5455 physicians. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2007;25:178–85. doi: 10.1080/02813430701430854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krohne K, Brage S. New rules meet established sickness certification practice: A focus-group study on the introduction of functional assessments in Norwegian primary care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2007;25:172–7. doi: 10.1080/02813430701267421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tellnes G, Sandvik L, Moum T. Inter-doctor variation in sickness certification. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1990;8:45–52. doi: 10.3109/02813439008994928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holdsworth LK, Webster VS, McFadyen AK. Physiotherapists' and general practitioners' views of self-referral and physiotherapy scope of practice: Results from a national trial. Physiotherapy. 2008;94:236–43. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bollag U, Rajeswaran A, Ruffieux C, Burnand B. Sickness certification in primary care: The physician's role. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2007;137:341–6. doi: 10.4414/smw.2007.11865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engblom M, Alexanderson K, Rudebeck CE. Characteristics of sick-listing cases that physicians consider problematic: Analyses of written case reports. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2009;27:250–5. doi: 10.3109/02813430903286286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Black C. Working for a healthier tomorrow. London: TSO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Department for Work and Pensions, Department of Health. Improving health and work: Changing lives, The Government's response to Dame Carol Black's review of the health of Britian's working-age population. London: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]