Abstract

Objective

The primary objective was to investigate the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of weight reduction using very low calorie diet (VLCD) in groups. The secondary objective was to investigate whether subsequent corset treatment could maintain the weight reduction long term.

Design

Participants, consecutively included in groups of 8–14 subjects, underwent three months of VLCD with lifestyle advice at group meetings. Subjects attaining ≥ 8 kg reduction were randomized to corset (A) or no corset (B) treatment for nine months. Weight was registered at all meetings and after 24 months. Costs were calculated using current salaries and anti-obesity drug prices as at 2008.

Settings

Primary care in Skaraborg, Sweden.

Subjects

A total of 26 men and 65 women aged 30–60 years with BMI ≥ 30−< 45 kg/m2.

Main outcome measures

Weight changes and costs of treatment.

Results

VLCD (dropout n = 14) resulted in a mean weight reduction of 20.1±6.6 kg (20 men) and 15.7±4.7 kg (57 women). These 77 subjects were randomized to treatment A (n = 39) or B (n = 38). Compliance with corset was only 20% after three months. After one year (dropout n = 17) weight loss was 11.7±8.1 kg (A) and 9.3±6.9 kg (B), p = 0.23 and after two years (dropout n = 22) 6.1±7.0 kg and 4.4±7.3 kg respectively, p = 0.94. Serum glucose and lipids were altered favourably. The cost per participant of treatments A and B was SEK 4440 and SEK 1940 respectively.

Conclusions

VLCD in groups was feasible and reduced weight even after one year. The cost of treatment was lower than drug treatment. Corset treatment suffered from poor compliance and could therefore not be evaluated.

Key Words: Family practice, group treatment, obesity, primary care, very low calorie diet

Very low calorie diet (VLCD), mainly used as an individual treatment in specialized clinics, gives a substantial weight reduction but weight is often soon regained.

VLCD during a three-month period in primary care was well accepted, and effective. It gave a similar weight reduction to when used in specialised clinics and reduced weight even after one year.

Corset treatment for nine months to maintain weight reduction could not be evaluated due to poor compliance.

The cost of VLCD treatment and group sessions with lifestyle advice was lower compared with pharmacological treatment.

Obesity, defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2, is a growing problem worldwide [1]. Obesity is associated with cardiovascular disease and increased cardiovascular risk [2], diabetes [3], gallstones [4], sleep apnoea [5], musculoskeletal disorders due to strain [6], reduced fertility in women [7], and psychiatric ill-health [8]. All are conditions commonly seen in primary care.

Treating obesity has proved very difficult. Diet and exercise with or without additional pharmacological treatment have shown limited success [9]. Only bariatric surgery gives substantial and lasting weight reduction and decreased mortality [10]. However, it is irreversible and expensive and cannot for practical reasons be offered to all patients. Consequently, there is a need for interventions that can be used in the primary care setting.

Individualized treatment with very low calorie diet (VLCD) in specialized clinics results in an average weight reduction of 13 kg for women and 20 kg for men after three months [11,12]. The use of VLCD in a structured form in primary care has only been reported in the Netherlands [13]. The weight-reducing effect of VLCD is temporary and must therefore be combined with other methods to maintain the weight loss. Garrow showed in 1981 [14] that weight reduction achieved by jaw fixation could be maintained by a nylon cord around the waist, prohibiting overeating. Anecdotally, weight reduction has been observed during treatment of scoliosis with the Boston corset, but no report has been found in the literature. Corset treatment could have similar effects to a nylon cord around the waist.

Individual treatment of obesity is most common, but group treatment may be more effective with a lower dropout rate and a lower cost [15]. Social support might also be an aid in weight maintenance [16] and the adherence to group sessions rather than the type of diet seems of importance for weight loss [17]. Group therapy is suitable for primary care, which has a tradition of multiprofessional teamwork.

The primary aim of this long-term follow-up study was to determine the feasibility of VLCD in groups and compare the costs with pharmacological and surgical treatment. The secondary aim was to examine whether treatment with a soft corset can maintain the weight loss achieved with VLCD.

Material and methods

Subjects

A total of 91 obese subjects in Skövde, Sweden, aged 30–60 years, were recruited after advertising in the local press or were referred from other physicians. The inclusion criteria were BMI ≥ 30 but < 45 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, breast feeding, diabetes type 1, serious skin, gastrointestinal, kidney, liver, lung, cardiovascular, and psychiatric diseases, malignancies, drug abuse, or eating disorders.

Clinical investigation

At inclusion in the study (from one day up to three months prior to start) medical history was taken and a physical examination was performed including measurement of height in cm, and weight to the nearest 0.1 kg, waist and hip circumference in cm, blood pressure in the supine position, right arm after five minutes’ rest (with a sphygmanometer) and a standard 12-lead ECG. Fasting blood glucose, serum uric acid, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides were analysed at inclusion and after one year using standard methods (Capio Diagnostik AB, Skövde).

Study procedure

VLCD treatment

Nutrilett (Cederroth International AB) with recommended calorie intake of 800 kcal per day was used and patients were advised to drink at least 2.5 litres of non-caloric liquids [12,18]. Patients were consecutively included in groups of 8–14 participants and followed up at six meetings at weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, and 9 by nurses and a dietitian. Weight and urinary ketone bodies were used as a measure of compliance and side effects were registered. At week 12 (completion of VLCD) the dietician recommended an individual calorie restricted diet.

Randomization

After VLCD and an investigation by general practitioners (GPs) the participants achieving at least 8 kg weight reduction were randomized (sex-stratified, using sealed envelopes) to corset treatment (A) or no corset treatment (B). All subjects received advice on healthy lifestyle throughout the whole study. The nurses and dietitian conducted six group meetings at weeks 2, 5, 7, 13, 21, and 29 after randomization and subjects with treatment A met the GPs at two additional, individual meetings at weeks 3 and 9.

Corset treatment

Soft corsets (Orthopaedic Technical Department, Skaraborgs Sjukhus, Skövde) were fitted to cover the torso from the xiphoid to the pubic region. The corset was to be used 12–16 hours per day, seven days per week for nine months. Compliance reported by the patients at the meetings was considered acceptable if the corset was used at least five hours per day and five days per week.

Economic calculations

Costs of treatment with VLCD and follow-up for one year was calculated as costs of investigation and follow-up by the GPs, nurses, dietitian (current salaries in 2008), and the cost of the corsets (n = 39, SEK 2500 each). Correspondingly, the costs (in 2008) over the counter (AUP price) for orlistat and sibutramin for one year's treatment, clinical examination, and follow-ups as recommended by the pharmaceutical industry were calculated. Finally the cost of bariatric surgery was calculated using data from the National Swedish Registry (NIOK) [19].

Statistical methods

A power calculation (Altman, Practical Statistics, 1998) was based on results from a clinical trial using a nylon cord to maintain weight loss [14]. Corset treatment was calculated to give an additional weight loss comparable to the nylon cord treatment. To achieve a power of 80% to detect a difference of 10 kg between the groups at < 0.05 significance after 12 months each group should include about 30 patients. The analyses were performed with SPSS statistical software (SPSS 15.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc. 1989–2006). Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviation and categorical data as frequencies. Differences between groups were calculated on the completers using ANOVA for continuous variables and for categorical variables using a chi-squared test. Analysis of weight differences between the groups were performed with nonparametric tests (Mann–Whitney). The significance level was set to p < 0.05.

Results

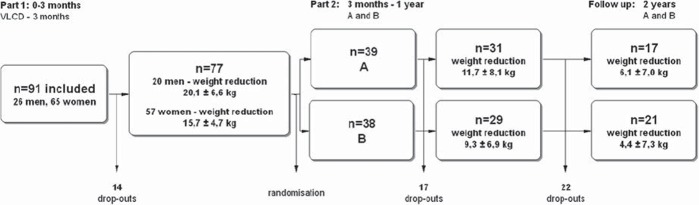

A flowchart of the study is shown in Figure 1 and the clinical characteristics of the subjects in Table I. A total of 91 subjects fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the study.

Figure 1.

Flow chart over study subjects during very low calorie diet, corset treatment, and follow-up. Notes. VLCD = very low calorie diet. Group A: Corset and lifestyle advice. Group B: No corset but lifestyle advice. The 14 subjects dropping out during VLCD did so very soon (within 2 weeks) after the start of the study.

Table I.

Clinical characteristics at baseline in subjects with corset (A) and no corset (B) treatment and in the dropouts (glucose and lipid values after one year in all completers.)

| Completers |

|||||||

| A n = 31 |

A 1 year |

p |

B n = 29 |

B 1 year |

p |

Dropouts n = 31 |

|

| Age, year | 46 (9) | – | 48 (9) | – | 41 (9)* | ||

| Systolic blood pressure mmHg | 136 (20) | – | 134 (18) | – | 131 (17) | ||

| Diastolic blood pressure mmHg | 79 (14) | – | 79 (10) | – | 80 (14) | ||

| BMI kg/m2 | 35.4 (3.4) | – | 36.1 (3.7) | – | 35.5 (4.1) | ||

| f-S-Glucose mmol/l | 5.18 (0.87) | 4.83 (0.50) | 0.004 | 5.28 (2.20) | 4.68 (0.61) | ns | 5.53 (2.38) |

| f-S-Triglycerides mmol/l | 1.60 (0.77) | 1.02 (0.49) | 0.001 | 1.58 (0.74) | 1.26 (0.77) | 0.014 | 1.88 (1.16) |

| f-S-Cholesterol mmol/l | 5.4 (0.9) | 5.2 (0.91) | ns | 5.6 (0.9) | 5.5 (0.95) | ns | 5.3 (1.2) |

| f-S-LDL mmol/l | 3.14 (0.85) | 3.02 (0.89) | ns | 3.25 (0.63) | 3.31 (0.83) | ns | 3.15 (1.03) |

| f-S-HDL mmol/l | 1.45 (0.30) | 1.64 (0.30) | 0.002 | 1.61 (0.77) | 1.57 (0.24) | ns | 1.38 (0.37) |

Notes: Values are given as means (SD). A: corset; B: no corset; BMI: body mass index; HDL: high density lipoprotein; LDL: low density lipoprotein; ns: not significant. *Significant difference between dropouts and the combined groups of completers (p = 0.006). There were no significant changes in glucose levels and serum lipids after one year between the groups (A and B).

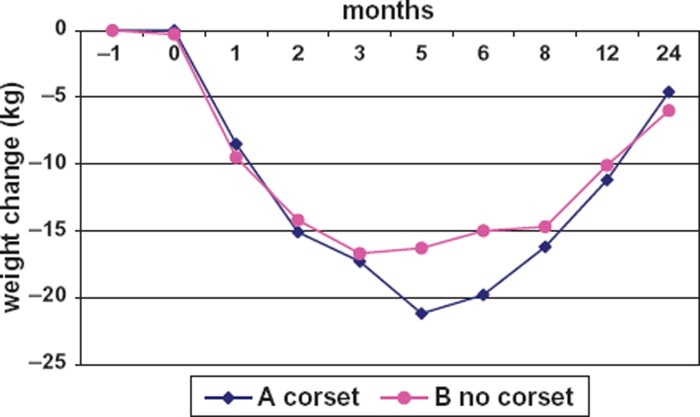

Weight change

Some 77 of the 91 patients achieved ≥ 8 kg weight reduction during VLCD. The mean weight reduction differed significantly between men (20.1 ± 6.6 kg) and women (15.7 ± 4.7 kg), p = 0.002. After 12 months there was no significant difference in weight reduction between the treatments 11.7 ± 8.1 kg (A) and 9.3 ± 6.9 kg (B), p = 0.23. The remaining weight reduction after 2 years was 6.1±7.0 kg in A and 4.4±7.3 kg in B, p = 0.94, Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Weight change of the completers during the two years of study. Notes: Initially, very low calorie diet for all participants for three months, subsequent corset (treatment A) and no corset (treatment B) for nine months and measurement of weight after 24 months. The value at −1 month was the mean weight at inclusion (n = 91), the value at 0 month shows the mean weight at VLCD start. The standard deviations of weight changes in A and B were at one month 2.9 vs. 2.0 kg, at 2 months 5.1 vs. 4.1 kg, at 3 months 5.7 vs. 4.8 kg, at 5 months 5.9 vs. 5.5 kg, at 8 months 6.2 vs. 5.3 kg, at 12 months 7.9 vs. 7.4 kg, and at 24 months 8.4 vs. 7.6 kg, respectively. The compliance with corset treatment (A) was 100% at start after VLCD completion, 33% after two months, 20% after three months, and 15% and 10% after five and nine months respectively.

Risk factor changes

In group A the levels of glucose and triglycerides were significantly reduced and HDL was significantly increased after one year compared with baseline. In group B the triglycerides were significantly reduced (see Table I). There were no significant changes between the groups (A and B).

Adverse effects

Few adverse reactions occurred during VLCD, mostly dizziness, gastrointestinal disturbances, dry skin, and one reported biliary colic. Improved sleep, less snoring (7 subjects), and reduced joint complaints were spontaneously reported. There were no adverse reactions during treatment A. The corset was perceived as uncomfortable.

Compliance/dropout

Dropouts during VLCD (n = 14) occurred mainly during the first month. The meetings were attended by 96% of the subjects and the compliance with VLCD measured by presence of ketones in urine ranged from 85% at the start to 45% at the end. The compliance with the corset treatment was poor: 33%, 20%, and 10% wore the corset two, three and nine months, respectively, after randomization (see Figure 2). As a consequence the effect of treatment A could not be evaluated. The dropout rate was continuous after randomization (see Figure 1). In total, 31 dropouts occurred during the first year. They were younger than the completers, but did not differ in clinical characteristics (see Table I). The dropout rate at the two-year follow-up was 56% in treatment A and 45% in treatment B.

Resources used in treatment of obesity

The resources spent during the first year were for the GP 112 hours, for the nurses 192 hours, and for the dietitian 90 hours. The total time spent per patient was 4.5 hours. Costs for the Public Medical Service were for individual and follow-up meetings in groups (10 participants) for one year, for the GP 1 hour and 40 minutes, for the nurses 52 hours, and for the dietitian 13 hours. The total cost per patient and year was calculated at SEK 4440 (treatment A) and SEK 1940 (treatment B).

The cost of orlistat treatment, 120 mg 3 times daily, was SEK 7500 per person and year according to the Swedish pharmacy. The patient's cost ceiling was SEK 1800 and the cost for the Public Medical Service was SEK 5700. In addition, two meetings of 30 minutes (GP) and 4.5 hours (dietitian) gave a total cost to the Public Medical Service of SEK 6870. If sibutramin 10mg (or 15 mg) daily was used instead the cost was SEK 4500 per year (SEK 2700 for the Public Medical Service). Including two meetings of 30 minutes (GP), 4.5 hours for the dietitian, and four hours for nurses (blood pressure control according to the information from the pharmaceutical company) the total costs to the Public Medical Service were SEK 4400. Costs for gastric bypass surgery by laparoscope, used in 75% of gastric bypass patients, were SEK 80 000 and for open surgery (used in 25% of patients) SEK 100 000 according to NIOK [19], late complications not included.

Discussion

This study shows that the result of VLCD group treatment of obesity in primary care is comparable with VLCD used individually in specialized clinics [11,12]. The cost of VLCD was less than treatment with orlistat or sibutramin. The corset used in this study was perceived as uncomfortable and suffered from poor compliance.

The initial VLCD resulted in a successful weight reduction and the good compliance may be attributed to recruiting by advertisement selecting highly motivated participants and also to the group treatment strategy [15–17]. As the weight loss was comparable with that in studies in different contexts [11,12] the results from VLCD might be generalized, at least to countries with similar healthcare organizations. The greater weight reduction in men is interesting and consistent with previously published results [11,20]. This study was not designed to explore the reasons for this difference.

Even if some of the lost weight was regained after one year, significant changes in lipid levels compared with baseline were observed as reported previously [17] and this implies that even a modest weight reduction reduces the risk factors for cardiovascular diseases.

After VLCD the meetings were less frequent and this might have contributed to the higher dropout rate (see Figure 1). The low compliance with wearing a corset did not seem to be counterbalanced by the extra contacts with the GPs. The individuals randomized to this treatment (A) had a similar weight gain and in practice ended up with similar treatment to those with treatment B. The dropout ratio, especially among younger participants, has been observed earlier [21] and after two years was high (about 50%), but comparable to other pharmacological studies [22,23]. In contrast, in a study of patients with newly diagnosed diabetes, better compliance with consultations after one year (73%) was shown [24], may be because diabetes is recognized as a more severe condition than obesity.

The cost of VLCD was lower than the cost of treatment with orlistat or sibutramin. In addition, studies of orlistat or sibutramin have reported a weight loss of 2.9 kg and 4.2 kg, respectively, after one year [25]. In the current study the weight loss after one year was 9–11 kg which gives a lower cost per kilo weight loss for VLCD than for orlistat or sibutramin (SEK 216 vs. SEK 2544 or SEK 1023, respectively). Surgical treatment of morbid obesity has a higher initial cost than non-surgical treatments but is the only method so far that gives substantial and lasting weight loss and thus it may be cost-effective in the long run [26].

Primary healthcare can reach more patients with obesity than specialized care. Consequently, the results of this study could encourage personnel in primary care to use VLCD and lifestyle advice in groups for weight reduction, for instance prior to surgical procedures or in combination with other treatments such as behavioural therapy to maintain weight loss. More studies on therapies suitable for primary care to maintain the reduced weight are needed.

In conclusion, we have shown that VLCD treatment of obesity in groups in primary care was feasible and cost effective compared with other non-surgical treatments. After one year, blood glucose and lipid levels changed favourably compared with baseline. The secondary objective, to evaluate the effect of corset treatment in maintaining the weight reduction, was inconclusive as corset treatment was not accepted by the majority of participants. Thus, due to the low compliance, corset treatment does not appear to be an option for sustained weight control.

Acknowledgement

The authors are very grateful to Eva Bergström, Pia Kyrk Bergsten, Christina Selvén, and Carina Dahl for their excellent work with the patients, to Salmir Nasic, biostatistician, Skaraborg Hospital, Skövde for valuable advice in statistical matters, and to Birgitta Lindberg for technical assistance in preparing the manuscript.

The regional ethical review board approved the study and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

This research was funded by the Skaraborg research and development council, Skaraborg primary care research and development council, Skaraborg Institute, the Swedish Union of General Practitioners, and Cederroth International AB

Conflicts of interests

None.

Referances

- 1.WHO. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;(i–xii):1–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson P, D’Agustino R, Sullivan L, Parise H, Kannel W. Over-weight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk. The Framingham Experience. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1867–72. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberti K, Zimmet P. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus, provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrlinger S. Gallstones in obesity and weight loss. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:1347–52. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012120-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Sousa A, Cercato C, Mancini M, Halpern A. Obesity and obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Obes Rev. 2008;9:340–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anandacoomarasamy A, Caterson I, Sambrook P, Fransen M, March L. The impact of obesity on the musculoskeletal system. Int J Obes. 2008;32:211–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehrmann D. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1223–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simon G, Von Korff M, Saunders K, Miglioretti D, Crane P, van Belle G, et al. Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:824–30. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avenell A, Brown T, McGee M, Campbell M, Grant A, Broom J, et al. What interventions should we add to weight reducing diets in adults with obesity? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of adding drug therapy, exercise, behavioural therapy or combinations of these interventions. J Hum Nutr Dietet. 2004;17:293–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2004.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sjöström L, Narbro K, Sjöström C, Karason K, Larsson B, Wedel H, et al. Swedish obese study. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torgerson J, Lissner L, Lindroos A, Kruijer H, Sjöström L. VLCD plus dietary and behavioural support versus support alone in the treatment of severe obesity. A randomised two-year clinical trial. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21:987–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torgerson J, Agren L, Sjöström L. Effects on body weight of strict or liberal adherence to an initial period of VLCD treatment. A randomised, one-year clinical trial of obese subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:190–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saris W, Koenders M, Pannemans D, van Baak M. Outcome of a multicenter outpatient weight-management program including very-low-calorie diet and exercise. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56:294S–6S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.1.294S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garrow J, Gardiner G. Maintenance of weight loss in obese patients after jaw wiring. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981;282:858–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6267.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minniti A, Bissoli L, Di Francesco V, Fantin F, Mandragona R, Olivieri M, et al. Individual versus group therapy for obesity: Comparison of dropout rate and treatment outcome. Eat Weight Disord. 2007;12:161–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03327593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elfhag K, Rössner S. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obes Rev. 2005;6:67–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sacks F, Bray G, Carey V, Smith S, Ryan D, Anton S, et al. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, proteins, and carbohydrates. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:859–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lantz H, Peltonen M, Agren L, Torgerson J. Intermittent versus on-demand use of a very low calorie diet: A randomized 2-year clinical trial. J Intern Med. 2003;253:463–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nationella Indikationer för obesitas-kirurgi [National indications for obesity surgery. National Board of Health and Welfare, Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions and Swedish Society of Medicine. 2007:53–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mustajoki P, Pekkarinen T. Very low energy diets in the treatment of obesity. Obes Rev. 2001;2:61–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lantz H, Peltonen M, Agren L, Torgerson J. A dietary and behavioural programme for the treatment of obesity: A 4-year clinical trial and a long-term post treatment follow-up. J Intern Med. 2003;254:272–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rössner S, Sjöström L Noack R, Meinders A, Noseda G. Weight loss, weight maintenance, and improved cardiovascular risk factors after 2 years’ treatment with orlistat for obesity. Obes Res. 2000;8:49–61. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansen D, Astrup A, Toubro S, Finer N, Kopelman P, Hilsted J, et al. Predictors of weight loss and maintenance during 2 years of treatment by sibutramine in obesity. Results from the European multi-centre STORM trial. Int J Obes. 2001;25:496–501. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juul L, Sandbaek A, Foldspang A, Frydenberg M, Borch-Johnsen K, Lauritzen T. Adherence to guidelines in people with screen-detected type 2 diabetes, ADDITION, Denmark. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2009;27:223–31. doi: 10.3109/02813430903279117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rucker D, Padwal R, Li S, Curioni C, Lau D. Long term pharmacotherapy for obesity and overweight: Updated meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335:1194–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39385.413113.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salem L, Devlin A, Sullivan S, Flum D. Cost-effectiveness analysis of laparoscopic gastric bypass, adjustable gastric banding, and nonoperative weight loss interventions. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]